Hadjin – Churches

Author: Varty Keshishian, 20/04/14 (Last modified: 20/04/14) - Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

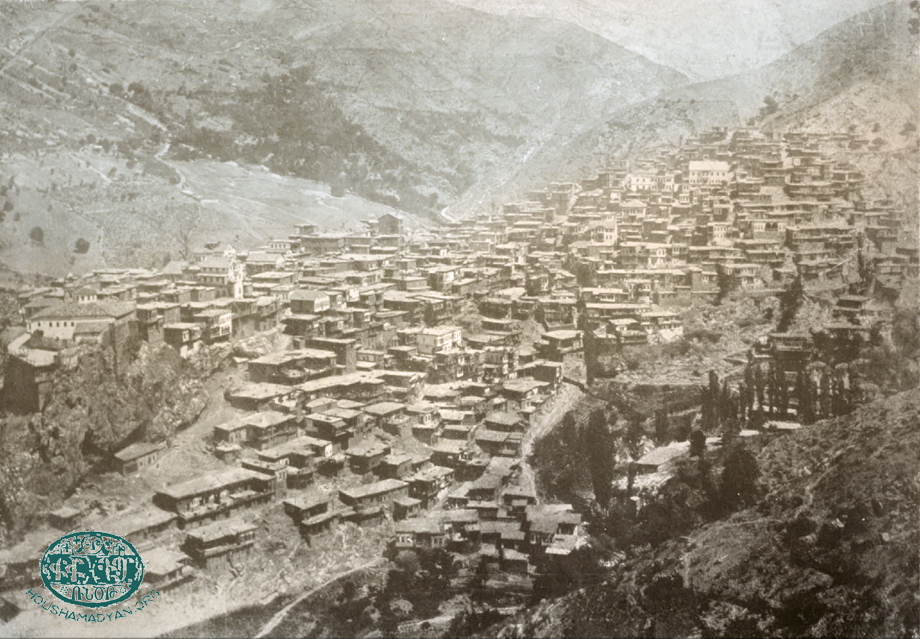

Hadjin had three Armenian Apostolic churches – Sourp Asdvadzadzin, Sourp Kevork and Sourp Toros. The first two were located in the Upper District (Veri Tagh), and the last in the Lower District (Vari Tagh).

Like all Armenian populated regions in the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians of Hadjin lived as a religious community centered on their churches. Their dedication and passion for religion, the church and church tradition, was just as pronounced as elsewhere. Thus, the 20-25,000 Armenians of Hadjin were faithful to their churches and the equally cherished Sourp Hagop historic monastery. Religious services at these churches were conducted by some twenty clergymen. At best, most had a rudimentary education. By trade they were weavers, shoemakers or farmers, because candidates for the priesthood were selected from the simple strata of society. It was sufficient that they could read and write, be able to hold a tune, and be devout and upstanding individuals. [1]

The obligation of the priests was to conduct church services, while the task of maintaining the upkeep of the church, managing its revenues and expenses and taking care of the schools, was entrusted to a prominent lay person who was called a “deputy” (yerespokhan). Each church had its chosen deputy who was recognized and certified by the presiding primate. [2] After the declaration of the National Constitution, in the mid of 19th Century, in Hadjin (as in all Armenian communities), neighborhood councils and parish meetings were conducted at the churches and they managed religious, church and educational affairs. [3]

Living expenses for the priests derived from donations made by the people and by specific fees when the clergy would conduct special services such as baptisms, weddings and funerals, house blessings on Christmas and Easter, visits to the sick, as well as voluntary donations for ordering special prayers.

All three Hadjin churches held services twice daily, in the morning and evening, and the Divine Liturgy was celebrated twice weekly. On Sunday morning, matins began an hour or two before sunrise. Residents, young and old, would hurry off to church carrying a lighted mokhragal (ash-pan). [5]

1) The Kerkyasharian family from Hadjin, 1910.

Standing (from left): Garabed Kerkyasharian, Verjine Kerkyasharian, Aharon Kerkyasharian, Kevork Kerkyasharian, Sara Kerkyasharian. Seated (from left): Eugénie Kerkyasharian (later Mamigonian), Mariam Kerkyasharian, Manuel Kerkyasharian (standing to the right of her mother), Stepan Keryasharian, Victoria Kerkyasharian.

Photograph taken in Adana (Source: Stepan Keryasharian collection. Courtesy of Antranik Dakessian).

2) The Tarpinian/Chilingirian family from Hadjin. Photograph taken in Adana, 29 June 1919 (Source: Vazken Tarpinian collection. Courtesy of Antranik Dakessian).

A very interesting custom in Hadjin was for the church beadle (jamgoch), carrying a thick staff in one hand and a lighted candle in the other, to walk through the town before sunrise, solemnly calling residents to the church for prayer. Stopping at each house, he would gently sing out and knock on the door thrice with his staff. [6] We have yet to come across this custom anywhere else. It was surely a local tradition, both fascinating and touching. As a unique sample of Hadjin folklore, we present the “Song of the Beadle” to our readers in its entirety.

Song of the Beadle

Blessed are Thee God

Praised are Thee God

Glorified are Thee God

Oh ye good Christians

Come to church service

Do not sleep or slumber

Open your ears, do not remain deaf

Do not tally for holy prayers

Oh ye good Christians

Come to church service

Heaven’s angels glorify

They take the spirit of the Righteous with light

They take the spirits of the Sinner with dark

Blessed are the Righteous

Cursed are the Sinners

We have come into this world to die

Judgment Day was made for sinners

Heaven was made for the righteous

Blessed are the Righteous, Cursed are the Sinners

The Devil’s death is late

The path of the Sinner is filled with thorns

Going to church is very pleasant

Oh ye good Christians

Come to church service.

Or else they sung Turkish verses:

Sabah oldu nur açıldı

Nurdan libaslar biçildi

Cennet kapısı açıldı

Buyrun ibadet haneye.

Sabah oldu kalkmazmısın

Dan yüzüne bakmazmısın

Sen Allahdan korkmazmısın

Buyrun ibadet haneye.

Zindanda çağrışır canlar

Hiç kimse olmaz imdat

Zalim şeytan cellat olmuş

Buyrun ibadet haneye.

Sağ yanında elvan olur

Sol yanında feygan olur

Günahkarlara hayıf olur

Kesilmeden dine gelin.

Translation:

Morning has come, light now shines

Clothes have been sewn from light

The door to Paradise has opened

Please come to church.

Morning has come, you haven’t risen

You don’t look into the face of the sinner

You do not fear God

Please come to church.

In the dungeon, souls cry out

No one will come to their aid

The cruel devil has come as an executioner

Please come to church.

A pastel of colors on your right

To your left, irritation

A warning to the sinners

Repent/ See the light before being destroyed.

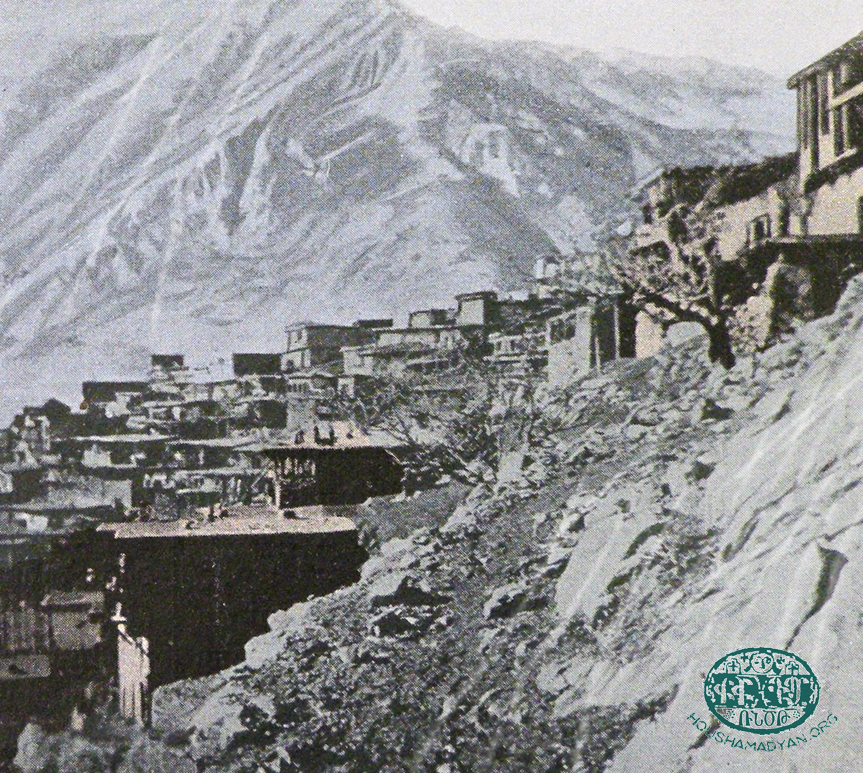

Sourp Asdvadzadzin

The church was built in the Hadjin fortress on a high cliff. The foundations must have been laid; around the same time that Armenians settled in the area and built the town after relocating there subsequent to the fall of the Armenian Cilician Kingdom in 1375. [8] Tradition also notes that some Armenians were taken as captives to Egypt after the fall of the kingdom. After being freed fifty years later, they were granted permission to return to their country. Fifty families found refuge in the eastern portion of the current Hadjin fortress, in the caves. Sometime later, the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem sent two bishops (Bartoghomeos/Barthelemy and Boghos/Paul) and a celibate priest (Hovhannes) to Hadjin. The clergymen take a cornerstone with them and use it to erect a fortress church and call it Sourp Asdvadzadzin. [9]

If we accept this storey, also corroborated by other sources, then St. Asdvadzadzin was probably built around 1425. [10]

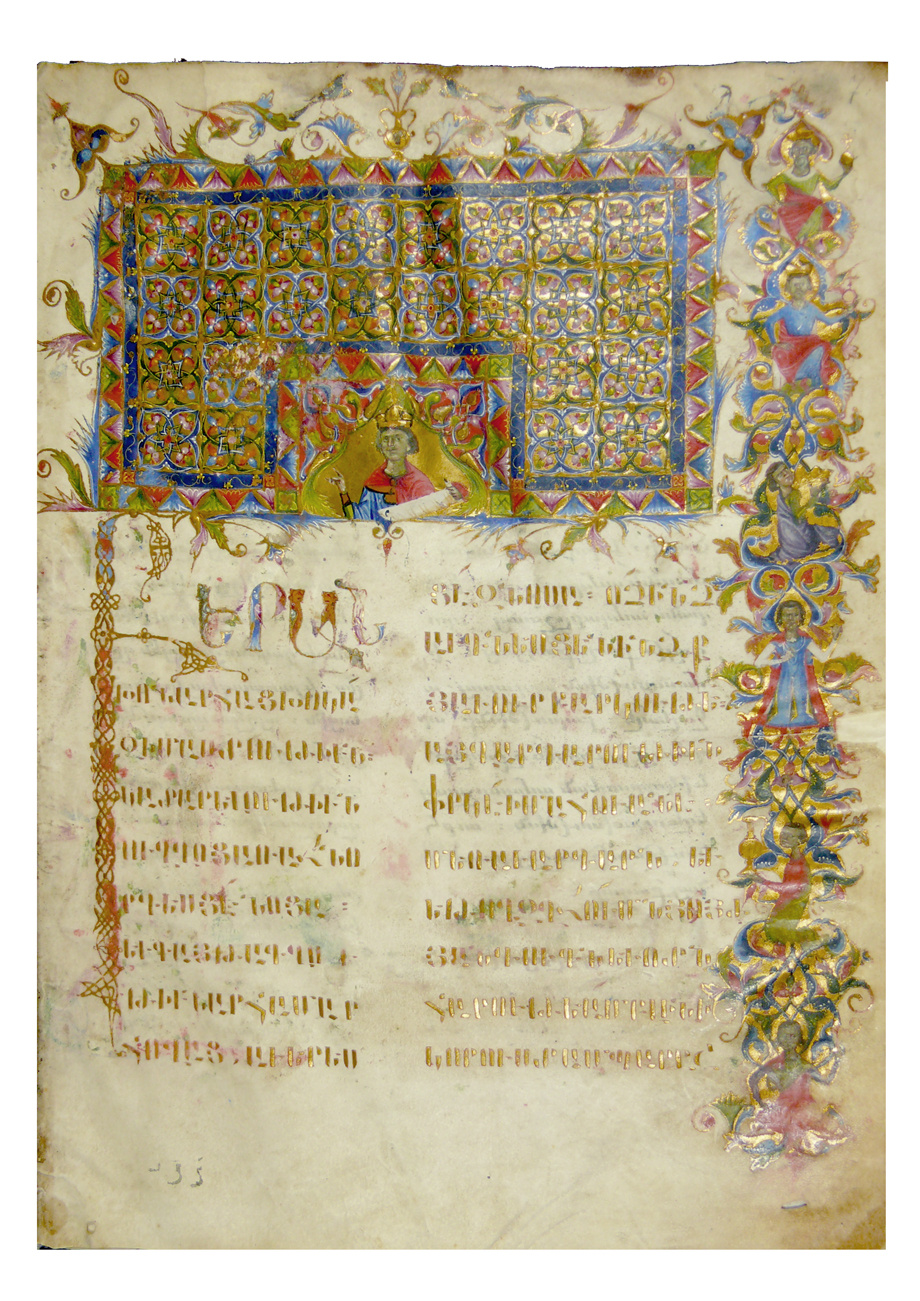

Manuscripts of singular value in terms of age and the art of calligraphy were kept at the Hadjin churches. Most had been transferred from the St. Hagop Monastery when it fell into ruin and disrepair. [11]

Hadjin native Sograd Topalian writes that there was an eight hundred year old handwritten Avedaran (New Testament) in St. Asdvadzadzin. Topalian says he had seen and read a diary noting that the manuscript was seized by the Armenian Divan Oghlu or Livan Oghlu. A prominent Hadjin resident, Erezian Hadji Manoug, is said to have purchased it for two purses (each containing 500 ghurush/kuruş) from Divan Oghlu. [12] The same manuscript was seized a second time by a large confederation of influential tribes dominated by the Kozanoğlu family. Once again a prominent Hadjin Armenian, Hadji Krikor, rescued the manuscript by paying a ransom of five hundred ghurush.

According to another diary source, the monastery didn’t have the funds to pay a ransom to the Kozanoğlu tribe. Later on, some twenty parishioners of St. Asdvadzadzin each donated 200 ghurush to buy it back. [13]

Dr. Kevork Kerkyasharian from Hadjin relates that a magnificent parchment New Testament was kept at St. Asdvadzadzin, noting that “With its binding and inlaid gold embellishments it bore the stamp of the era of the Cilician dynasty.” [14] It is believed that this and numerous other Hadjin church treasures were seized by Ottoman authorities during the eviction and massacres of the First World War.

Let us however return to the facts at hand regarding the St. Asdvadzadzin Church. Pastor Sarkis Devirian relates that he read an inscription in a manuscript book kept at the church, according to which the church had once been burnt down and another time destroyed by an earthquake, and that it had been rebuilt twice, but that no dates were mentioned. [15]

Further information we know about St. Asdvadzadzin deals with more recent times. Natural disasters and devastating fires weakened the foundations of the church on numerous occasions. But the church remained standing. In 1861, large boulders from a 200 meters high cliff above the church suddenly tumbled down one night, destroying many homes that had been built one next to another at the base of the fortress. Sleeping residents were killed in the landslide. But the fortress and the church were left undamaged. [16]

In 1894 a fire broke out near the church, burning 700 homes in its wake. Many residents were left homeless, but once again the church itself remained unscathed. An interesting side note to this incident is that a relief committee was set up to care for the victims. Comprised of local Turkish officials, the Hadjin Armenian Church Primate and the Armenian Protestant Church pastor, the committee disbursed funds allocated by the government. [17]

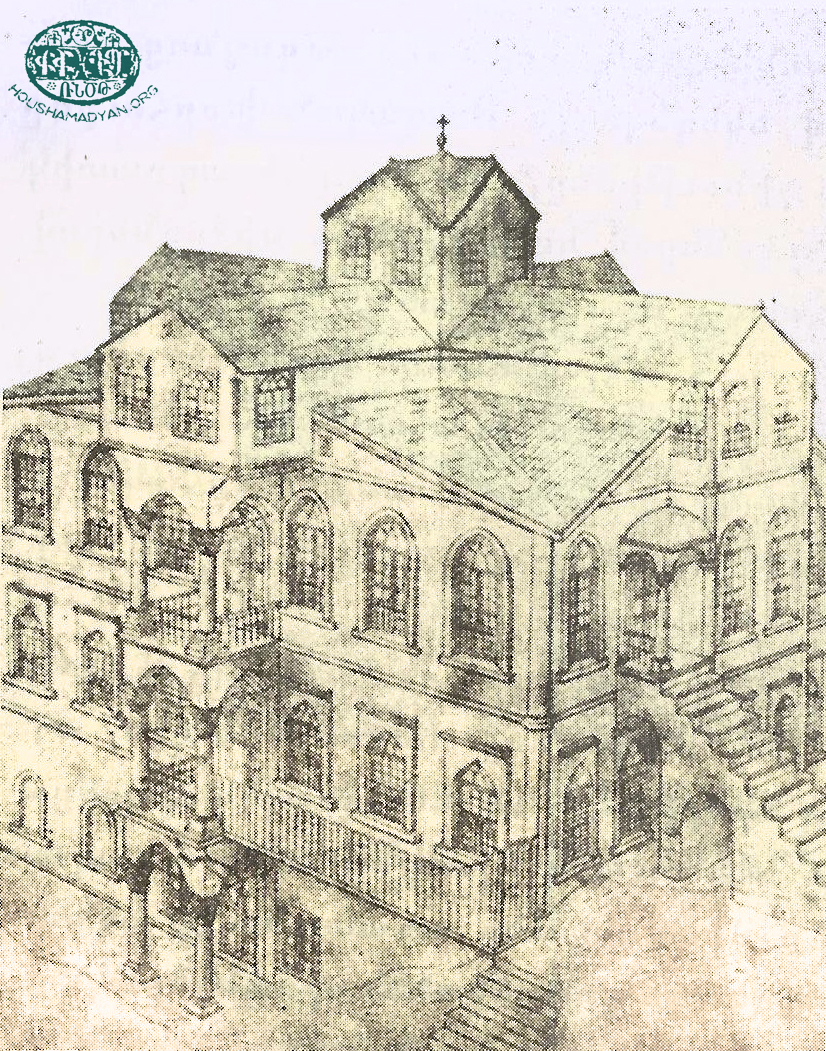

We have no information about the establishment of a school that operated next to the church. Hadjin Primate Archbishop Bedros Saradjian ordered the construction of a huge five storey building on the cliffs next to St. Asdvadzadzin. The first floor housed a kindergarten; the second and third floors were classrooms; the fourth housed the diocese office; and the fifth was a theater hall. Of note is that this building was partially funded by donations made by the impoverished but charitable residents themselves. The rest were contributions made by Hadjin compatriots living in the United States. [18] We should add that this stone hewn edifice, in its scope and size, was one of the prominent buildings in Hadjin. [19]

Clergy who served at St. Asdvadzadzin include: Father Boghos Pazian, Father Hovhannes Der Hovhannesian, Father Simeon Hampartsoumian, Father Sarkis Arsenian, Father Toros Der Hovhannesian, Father Kasbar Kalenderian, Father Krikor Der Hampartsoumian and Father Hagop Koyoumdjian. [20]

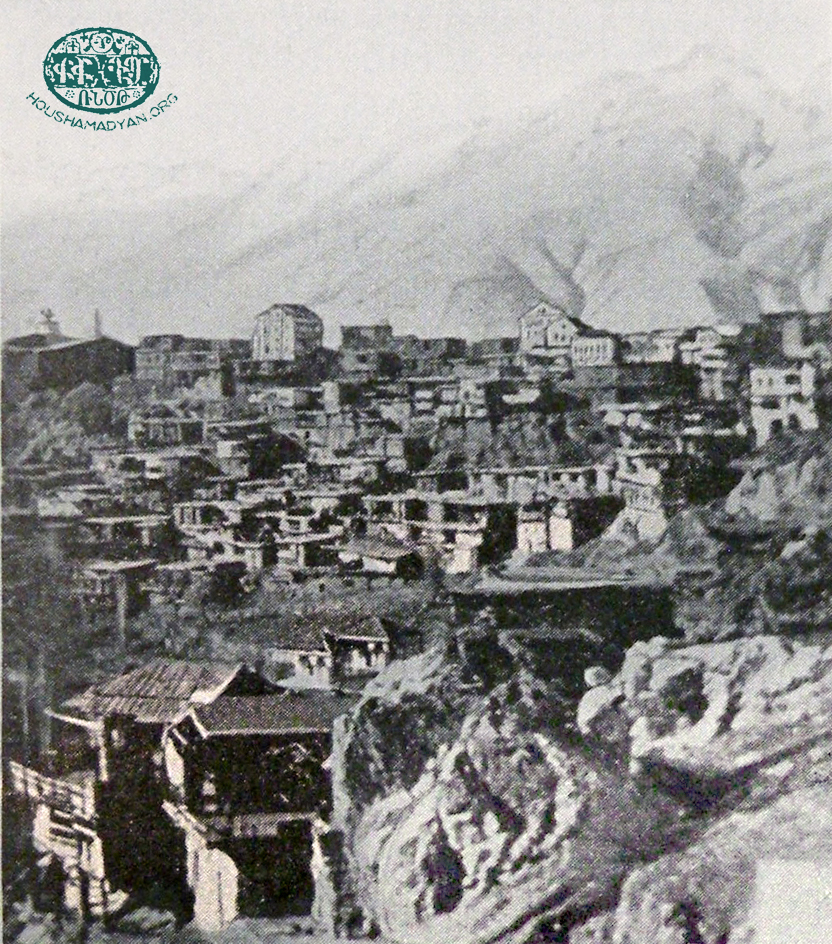

Sourp Kevork

Hadjin’s St. Kevork Church was built much later, even though sources attest to the fact that a small chapel existed on the site in ancient times. The new church began to be built in 1844, when Mardiros Agha Mangerian served as “deputy”. With the death of Mangerian, the church remained unfinished and was finally completed in 1855 through the efforts of Sarkis Agha Toursarkisian, the new “deputy”. [21] Toursarkisian also had a diocesan office and a seminary built nearby.

The oldest and largest khan (caravanserai-roadside inn) in Hadjin, the Veri Tagh khan, was the property of this church from ancient times. Merchants from the surrounding villages and towns would often stay at this khan. The Kozanoğlu tribe also seized this khan from the Armenians. In 1883, Cilician Catholicos Mgrdich Kefsizian took the case to court and won. The khan was returned to St. Kevork. [22]

Based on the accounts of Hadjin luminaries, St. Kevork Church contained many old manuscripts taken from the St. Hagop Monastery. In 1907, Dr. Kevork Kerkyasharian, who was a teacher at the school affiliated with St. Kevork Church and who served as its sacristan at the same time (in whose care was entrusted the church’s treasury), attests that one of the unique manuscripts in the collection was the parchment New Testament at the Trazarg Monastery of King Hethoum. The king had gifted it to this monastery located near the city of Sis. The writer then recounts that he had the opportunity to leaf through this New Testament when it was placed on the altar as an adornment on church holidays. He says that the book became an object of wonder for foreigners passing through Hadjin. [23]

According to Dr. Kerkyasharian’s description, this priceless New Testament was adorned with a magnificent silver leaf binding, silver clasps, and penned by a master calligrapher, giving the impression of a printed book. It is also said that each of the four Gospels ended with a memo written by King Hethoum II regarding the gifting of the New Testament to the Trazarg Monastery. [24] While the description is quite insufficient, it is enough to assume that this royal manuscript was a masterpiece of Cilician calligraphy and miniature art.

According to a certain memoir, due to a succession of droughts the people of Hadjin couldn’t pay the taxes they owed to the Kozanoğlu tribe. Thus, they handed over the Hethoum New Testament to the tribe in lieu of the taxes they owed for the year. When the year ended and the people were still not able to pay, one of the local deputies, Telesemian Hadji agha stepped in and paid two years’ worth of taxes and had the book returned. He had the following memoir written on the occasion: “Telesemian Hadji agha paid many silver pieces and liberated the New testament from illegal hands and placed at the door of the St. Kevork Church in memory of his parents.” [25]

It is said that this valuable manuscript contained another important notations regarding the relocation of the Hethoum New Testament; as to how it was moved from Trazarg to other locations, how it reached Hadjin, etc. Sadly none of these entries have been preserved. [26]

The next testimony regarding St. Kevork Church references the great fire of 1883 that devastated almost half of Hadjin, starting from the church all the way to the neighborhood of Gelig. The church wasn’t damaged even though the fire burned close by, but its khan, which had been taken back from the Kozanoğlu tribe with great difficulty, was destroyed. On half of its land, in 1844, the benefactor Hadji Agha Avedik Terzian built some rooms and handed them over to St. Kevork as a gift. On the other half, he ordered the construction of the municipality building. [27] In 1909, Hadjin Primate Archbishop Nerses Tanielian ordered the construction of a large school building next to the St. Kevork Church. [28]

Clergy who served at St. Kevork include: Archpriest Sdepan Yergatakordzian, Father Krikor Misalian, Father Toros Meshian, Father Yeghishe Yergatakordzian, Father H. Tetvertsian and Father Sdepan Yergatakordzian. [29]

Sourp Toros

This church was located in Hadjin’s Yaghe district. While the church structure itself was built in more recent times [30], the history of St. Toros (just like St. Asdvadzadzin and St. Kevork) dates back to Armenian Cilician Kingdom. According to the chroniclers of Hadjin’s history, there was an ancient chapel in the garden opposite the church we know as St. Toros. Tradition says it was built by Prince Toros I of Cilicia (?-1129) and gifted to refugees. [31] This is why the church was consecrated with the name St. Toros.

The old folk of Hadjin recount that the woodlands opposite St. Toros (the southern portion of the town) had been settled by the Greeks of old and that a chapel also existed. Later on, as Armenians built houses and moved to the area, they attended this chapel for prayers. [32]

We should add that the Armenian geographer of the 19th Century, Ghougas Indjidjian, doesn’t mention St. Toros when listing the Armenian Apostolic churches of Hadjin along with St. Asdvadzadzin and St. Kevork [33]. Thus, we must infer that St. Toros was a chapel for a long time. St. Toros also had a school.

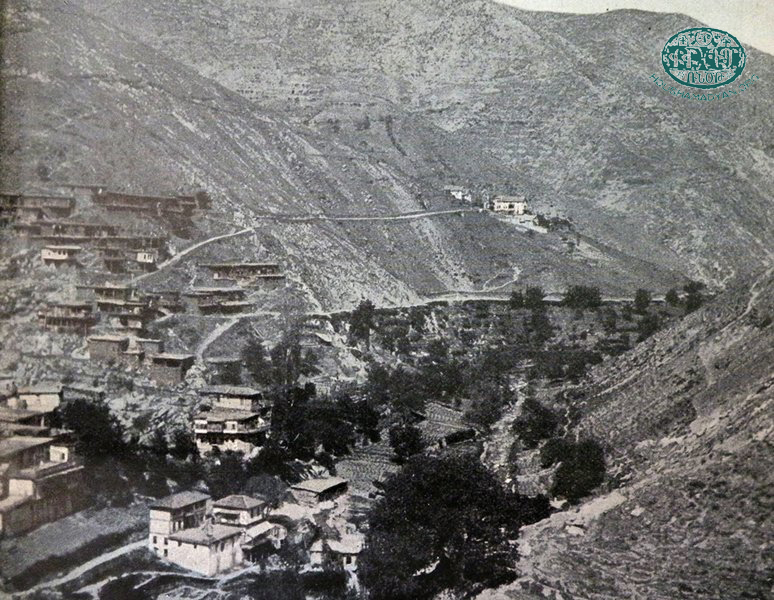

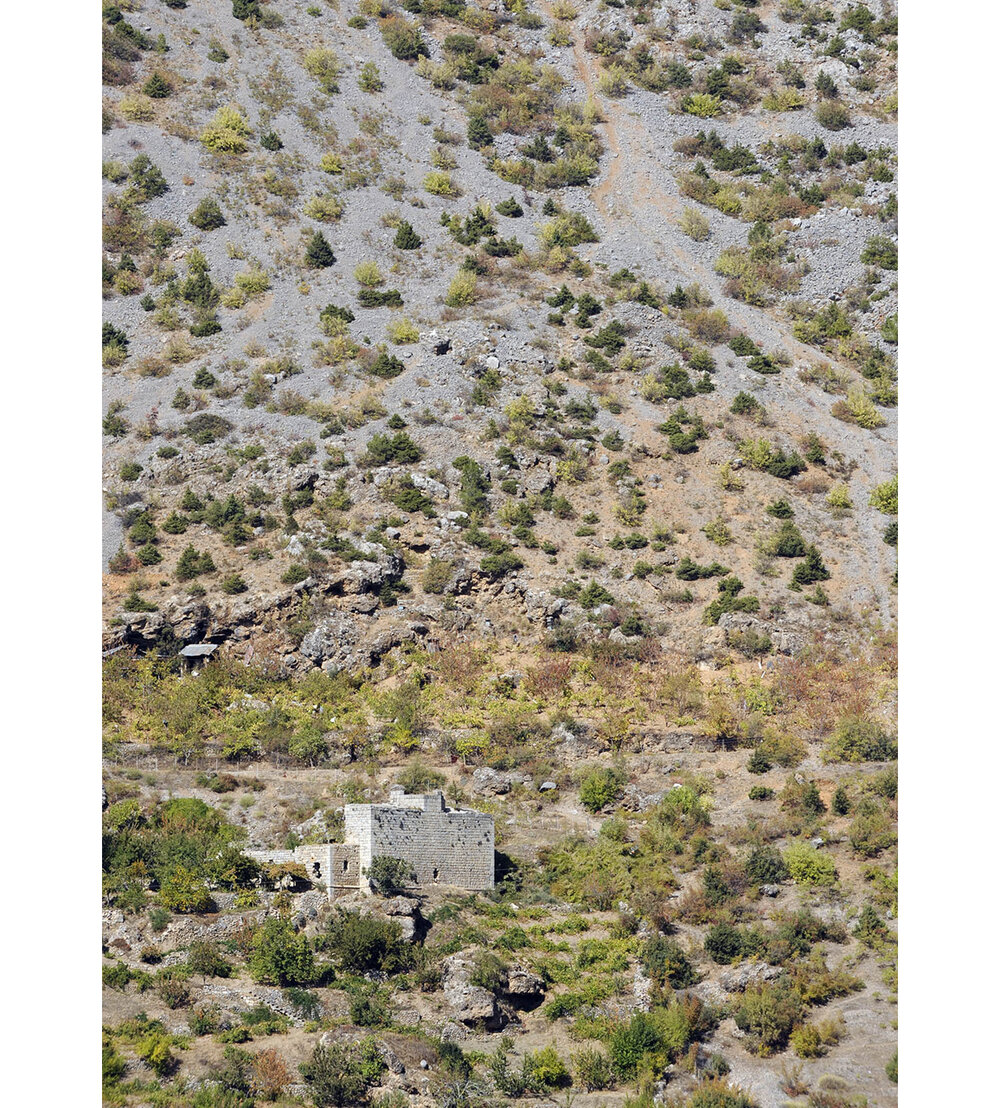

Sourp Hagop Monastery

In addition to the three aforementioned churches, this monastery stood on the slopes of a mountain with the same name (Hagop) in the western portion of the town. It was encircled with solid and high walls and the cold and clear waters of a spring flowed nearby. [34]

According to sources, St. Hagop Monastery was built under the supervision of Archbishop Khachadour in 1004. [35] In 1900, during the restoration of the monastery, an inscription placed on one of the dome’s pillars verifies the date of the monastery’s founding. [36]

The next piece of information about the monastery refers to 1554, when it was renovated for the first time. Thus, it was built in 1004 and renovated in 1554, which is confirmed in the works of Ghougas Indjidjian.

Thus, St. Hagop Monastery serves as the oldest proof of an Armenian presence in Hadjin [37]. At the same time, if we accept the fact that the monastery existed before the founding of Hadjin itself, then we can conclude that the history of the monastery is closely connected to history of the town’s formation and growth, and that the monastery served as one of the prime pillars on which the local Armenian community was formed.

Like all Armenian medieval monasteries, St. Hagop was also a center of learning and science. In the old days, when there were no schools in the town, the monastery served as the sole educational institution where the young people could attend. [38]

The Armenian girls' school next to the Sourp Asdvadzadzin Church (Source: H.B. Boghosian, General history of Hadjin and the neighboring Kozan-Dagh Armenian villages [in Armenian], Los Angeles, 1942)

During its centuries old history, St. Hagop graduated many clergymen, including catholicoi, archbishops and archimandrites. Hand-written manuscripts produced by the monastery’s archimandrites have also reached us. The Armenians of Hadjin are indebted to St. Hagop Monastery for educating and preparing the teachers and clergy who ran their churches and schools.

Abbots at St. Hagop include Archbishop Khachadour (1554), Archbishop Movses (1607), Archbishop Hovhannes (later Catholicos of Sis, 1719-1726), Archbishop Sarkis (1820), Archbishop Boghos (1826), Archbishop Boghos Der Melkonian (1854-83), Bishop Hovhannes Kazandjian (1885-92), Bishop Nerses Tanielyan (1909) and Bishop Bedros Saradjian (1910-1920). [39]

The monastery was subject to much abuse at the hands of the Kozanoğlu tribe that reigned over Hadjin and to whom residents paid tax. It is recounted that during the 1850s and 1860s the monastery was pillaged by Hadji Bey and Yusuf Bey in succession.

St. Hagop was also a pilgrimage site much loved by the people of Hadjin. It had many rooms especially to house pilgrims. On the holiday of St. Hagop, almost all the residents of Hadjin and the surrounding villages would start to walk up to the monastery at midnight to attend religious services and hold festivities. Visitors from faraway would spend weeks at the monastery. During these celebrations the monastery’s surrounding would be turned into a market. There would be horse races, and riders would split into two teams bearing sticks. They would hit riders from the opposing side and try to steal their hats. [40]

In 1882, Catholicos Mgrdich Kefsizian established the second theological seminary at St. Hagop Monastery. This was the second such school after the one established in Ayntab in 1873. (The one in Ayntab had closed down two years later for various reasons). Due to the fire that engulfed Hadjin the school was forced to close its doors before a year had passed. The seven seminarians, all from Hadjin, were transferred to the Mother Cathedral at Sis in early 1884. In May of the same year, they returned to St. Hagop and continued their education under the tutelage of Minas Toursarkisian. [41]

St. Hagop was renovated a second time in 1885 by Archbishop Bedros Der Melkonian. [42]

During the renovations to the monastery in 1900, a large building was built nearby to serve as a school and orphanage where a large number of orphans were cared for and provided with an education. [43]

During the 1909 anti-Armenian massacres in Cilicia, St. Hagop was laid to ruin. It was later restored and turned into an orphanage. [44]

The Armenian Catholic Church

As in other Armenian communities, Catholicism was introduced to Hadjin the late 1860s. In a short time many Hadjin Armenian Apostolic families embraced the new doctrine. [45]

Initially, they gathered at the home of the Ghoulebdjian family. Later, they moved to an area near the fortress and built a church. It was destroyed in the Great Fire that befell Hadjin in 1884. [46]

In 1892, due to the efforts of the Armenian Catholic community and His Eminence Terzian, two huge buildings were erected. The architect was Master Toros Babahekian from Hadjin. Each was a three storey building. One served as a residency and a boys’ school. The other served as a nunnery and the Sisters of Immaculate Conception girls’ boarding school. [47]

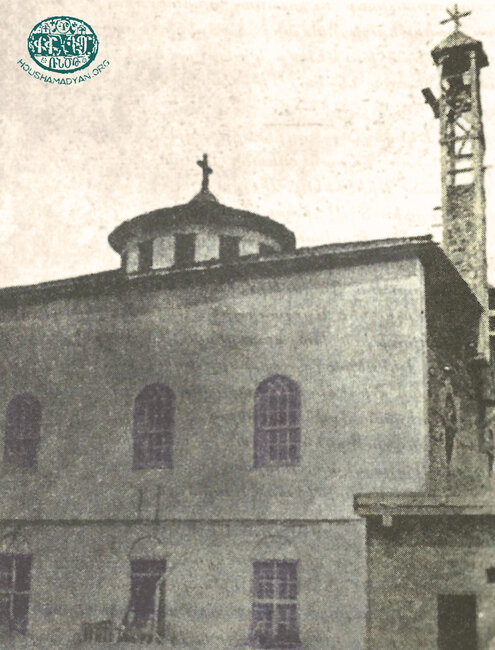

In the early 1900s, a large stone church was built at the site in order to withstand impending fires and to shelter great numbers of people. [48]

Armenian Protestant Churches

Protestantism was introduced to the Hadjin area in the early 1860s by American missionary Jackson Coffing. [49] Settling in Hadjin, he and his wife, Josephine Coffing, began to proselytize evangelical ideas and preach the Bible. Other Evangelical missionaries soon arrived in Hadjin from Ayntab to foster an Evangelical movement. The first church was created in 1867 with a small number of adherents. At first, they gathered at the house of Nazaret Dardaghanian to hold services. As their numbers gradually increased, the First Armenian Evangelical Church was built in the town’s Upper District. [50]

By 1878, this church proved to be too small and a number of nearby homes were purchased to build a much larger edifice. In the spring of 1879, Dr. Thomas Christie and his wife, Carmelite, came to Hadjin from Marash specifically to assist in the construction of the new church. It was then decided prudent to ordain Sarkis Devirian as pastor. The September 15, 1879 service took place outdoors due to the small confines of the church. It was after this that residents were asked to contribute towards the building of a bigger church. The people eagerly participated in the church fundraising drive. Work commenced on the new church in 1880 and was competed two years later. [51] The lower floor of the new building served as a coed school, and the upper floor as the church. Of note is the fact that the Armenian Evangelical Church of Hadjin, from the day it was founded, was always independently self-sustaining. It was the parish that paid all the church expenses, even the pastor’s salary. There was no financial assistance from the outside; an exceptional case for the era. [52] According to 1903 data, the church had over 1,000 members. [53]

Due to the ever growing number of Evangelical believers in the southern portion of Hadjin and because the first church was some distance away, in 1889 [54] a Second Armenian Evangelical Church [55] was built on a large parcel of land purchased in the lower section of the fortress. This two storey building also served the spiritual and educational needs of the district. The first floor served as a coed kindergarten and primary school and the meeting hall was on the floor above. [56]

The two churches both had primary schools with a combined enrollment of 630 pupils, and separate Men’s and Women’s Associations. [57] Prior to WWI, the Armenian Evangelical community in Hadjin numbered around 300 households. [58]

Pastors serving at the First Armenian Evangelical Church included Panos Karageozian and his assistant Senior Khodja Shiredjian, Sarkis Devirian, Sarkis Torian, Dikran Redjebian, Garabed Haroutunian and Haroutiun Khachadourian. Pastors at the Second Armenian Evangelical Church included Avak Shiredjian, Sdepan Hovhannedian, Krikor Kerkyasharian, Dikran Kaladjian and Levon Soghovmeyan. [59]

- [1] H.B. Boghosian, General history of Hadjin and the neighboring Kozan-Dagh Armenian villages [in Armenian], Los Angeles, 1942, p. 348.

- [2] Ibid.

- [3] Ibid.

- [4] Ibid, p. 350.

- [5] Ibid, p. 348.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] Ibid, pp. 348-349.

- [8] We come across notes regarding the town of Hadjin starting from the 13th century. Thus its history isn’t very old. Based on historical evidence and information, researchers have concluded that Hadjin was established after the fall of the Cilician Armenian dynasty by Armenian refugees. It is believed that the first refugees were residents arriving from Harkan, an Armenian populated town not far from Hadjin. With refugees gradually arriving from elsewhere in greater numbers, the foundations were laid for the town we know as Hadjin. (See Boghosian, pp. 120-121).

- [9] Boghosian, pp. 121, 343.

- [10] Ibid, p. 120.

- [11] Ibid, p. 344.

- [12] After the fall of the Cilician dynasty, Hadjin and the surrounding area was governed by influential Armenian princes. In the 1640s, when representatives of the Kozanoğlu tribe began to establish their rule over the Taurus Mountains, Hadjin and nearby villages also passed under their control, despite the fact that they were primarily governed directly by Armenian princes. Until the 19th century, the central Ottoman state had a formal presence in these regions. (See Boghosian, p. 158).

- [13] Boghosian, p. 356.

- [14] Ibid, p. 346.

- [15] Ibid, p. 343.

- [16] Ibid, p. 152.

- [17] Ibid, p. 156.

- [18] Ibid, p. 450.

- [19] Ibid, p. 144.

- [20] Ibid, p. 362.

- [21] Ibid, p. 347.

- [22] Ibid, p. 148.

- [23] Ibid, p. 344.

- [24] Ibid, p. 345.

- [25] Ibid.

- [26] Ibid.

- [27] Ibid, p. 148.

- [28] Ibid, p. 450.

- [29] Ibid, p. 362.

- [30] Pastor Sarkis Devirian recounts that his mother and other women carried water for the construction of the building sometime in the 1880s. (See Boghosian, p. 347).

- [31] Ibid, p. 347.

- [32] Ibid.

- [33] Gh. Indjidjian, Geography of the four corners of the world; Vol. 1 [in Armenian], Venice, 1806, p. 318.

- [34] See Boghosian, p. 350; H.H. Vosgian, Monasteries of Cilicia [in Armenian], Vienna, Mkhitarist Press, 1957, p. 260.

- [35] Boghosian, p. 350.

- [36] Ibid, p. 350.

- [37] Cilicia, “Araks”, p. 302.

- [38] Boghosian, p. 412.

- [39] Ibid, p. 413.

- [40] Ibid. pp. 352, 532.

- [41] Ibid, p. 353.

- [42] ibid. pp. 350-351.

- [43] Ibid, p. 353.

- [44] Ibid, p. 351.

- [45] Ibid, p. 410.

- [46] Ibid.

- [47] Ibid, p. 411.

- [48] Ibid.

- [49] Ibid, p. 380.

- [50] Ibid, p. 384.

- [51] Ibid.

- [52] Ibid.

- [53] Yeghia S. Kassouny, The Path of Light: History of the

- Armenian Evangelical Movement [in Armenian], Beirut: American Press, 1947, p. 216.

- [54] H. Boghosian sets 1878 as the date of the founding of the First Armenian Evangelical Church of Hadjin. This is most likely due to an error. According to above cited work of Pastor Yeghia Kassouny, it was founded in 1889. (See Kassouny, p. 217)

- [55] Kassouny, p. 217.

- [56] Boghosian, p. 385.

- [57] Kassouny, p. 217.

- [58] Boghosian, p. 385.

- [59] Ibid, p. 386.