Mush - Churches and Monasteries

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 19/12/2016 (Last modified: 19/12/2016) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

Churches of the City of Moush

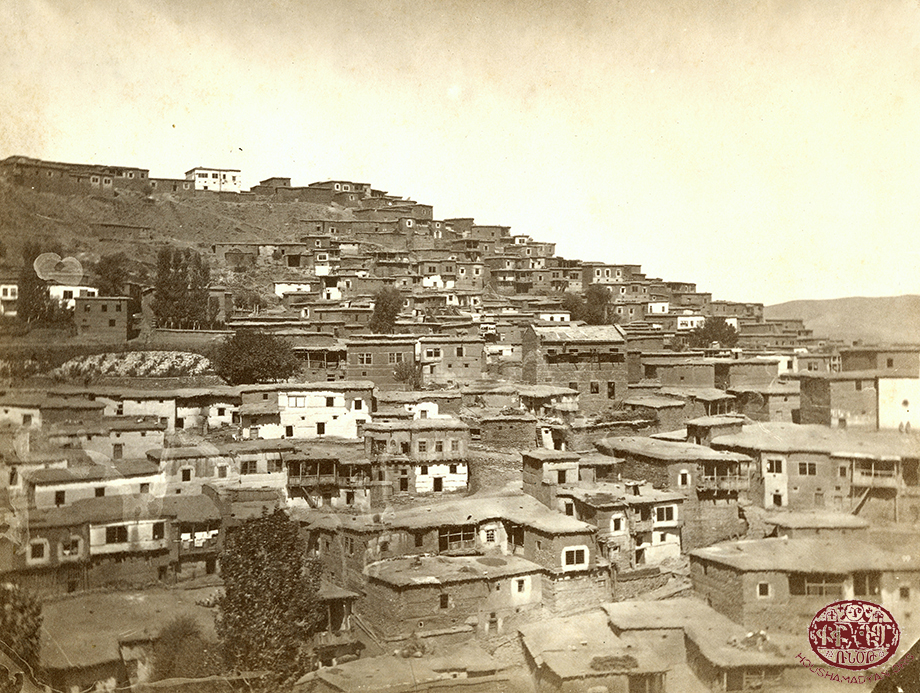

The City of Moush was the heart of the Kaza of Moush in the Vilayet (Province) of Bitlis. Consequently, the city was the seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Moush (Daron).

According to the Armenian Patriarchate, in 1913-1914, on the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the city was home to 7,435 Armenians (1,146 households) [1]. Other sources contend that the Armenian population of the city was 12,000 [2] or 12,450 (1,376 households) [3].

At the outset of the 20th century, Armenian churches functioning in the city’s various neighborhoods included –

Saint Harutyun (Verin Neighborhood – 495 households, 4,570 individuals) [4]. The date of construction is unknown [5]. On the eve of the genocide the church was served by Archbishop Yeghishe Barsamian, Father Ghevont Der Ghevontian (killed during the genocide), and Father Kalousd Der-Kalsdian (killed during the genocide) [6].Saint Harutyun (Verin Neighborhood – 495 households, 4,570 individuals) [4]. The date of construction is unknown [5]. On the eve of the genocide the church was served by Archbishop Yeghishe Barsamian, Father Ghevont Der Ghevontian (killed during the genocide), and Father Kalousd Der-Kalsdian (killed during the genocide) [6].

Saint Marine (Saint Marine Neighborhood – 374 households, 3,460 individuals) [7]. The date of construction is unknown [8]. On the eve of the genocide the church was served by Father Zachariah Der-Zakarian [9].

Saint Kevork (Saint Marine Neighborhood). Built in 1830 (1246 AH) [10]. On the eve of the genocide the church was served by Father Adom Parseghian [11].

Holy Virgin Church (also known by the name of Sheg Avedaran), alongside the adjacent Saint Minas Chapel (Tsor Neighborhood – 312 households, 2,750 individuals) [12]. The date of construction is unknown [13]. On the eve of the genocide the church was served by Father Hovhanness Der-Asdvadzadourian, Father Sahag Posdoyan, and Father Avedis Der-Avedisian [14].

Saint Sarkis (Prood Neighborhood – 145 households, 1,330 individuals) [15]. Built in 1136/1137 (531 AH) [16]. On the eve of the genocide, the church was served by Father Yeghishe Alamsharian [17].

Saint Giragos (Jikrashen Neighborhood – 50 households, 340 individuals) [18]. The date of construction is unknown [19]. In 1914, the clergyman serving this church had passed away, and the congregation was being served by priests from nearby neighborhoods [20].

Other churches that still stood in the city, but were not functioning, included the Saint Avedaranots, Saint Gregory the Illuminator, Saint Sdepanos, and Sourp Prgitch (Holy Savior) churches [21].

According to contemporaries, the most impressive and beautiful of the city’s churches was the Saint Marine Church. The oldest was the Holy Savior Church, mentioned in historic records in relation to the local Armenian population’s uprising against Arab domination in 851-852 [22]. In general, churches in the city of Moush were not particularly noteworthy from the standpoint of architecture. A contemporary described them as “insignificant, dark, and gloomy buildings” [23].

The Holy Virgin Armenian Catholic Church was also located in City of Moush [24].

Churches of the Moush Valley

In the second half of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, there were more than 100 Armenian or mixed-population villages scattered across the Moush Valley (the area of the Moush Valley roughly corresponds to the administrative area of the Moush Province) [25]. Almost every village had a functioning church and serving clergy.

Villages of the Moush Valley that were home to a sizeable population of Catholic Armenians included Norshen, Oghounk, and Arinch [26]. Protestant communities were active in the Armenian-populated villages of Havadorig, Mogounk, Hounan, and Terkevank.

Below is a list of functioning churches in the villages of the Moush Valley, and information regarding the clergymen serving in these churches. The information was compiled using data from the Armenian Patriarchate’s 1878, 1902, and 1913-1914 censuses and other complementary data [27]. Village churches for which no serving clergymen are listed were being served by clergy from nearby villages in which more than one of them was present.

Apelpuhar

Places of worship: 1) The Holy Virgin Church (stone-built, circa 1182); 2) Saint Kevork Monastery (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins).

Alatin

Places of worship: Sourp Amenaprgitch (Holy Savior) Church.

Alyank

Unnamed church.

Aliklpon

Places of worship: 1) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (built circa 1715); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Nerses.

Alizerna

Saint Giragos Church (built circa 1097).

Alichan

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built circa 1786); 2) Saint Talile Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins).

Alvarinch

Places of worship: 1) Saint Hagop Church (built of wood, circa 1748); Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Krikor.

Aghpenis

Saint Minas Church.

Aghchan

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood, circa 1815); 2) Saint Toros Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Ghevont Der-Markarian and Father Avedis Giragosian.

Aragh

Places of worship: 1) Saint Giragos Church (built circa 1427); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Mgrditch Der-Mgrdchian and Father Garabed Asmarian.

Arinch (Catholic Armenian Village)

The Holy Virgin Church (with its three altars).

Arinchvank

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built in 1233); 2) Unnamed monastery (ruins).

Arnisd

Places of worship: 1) Saint Hovhanness Church (built in antiquity); 2) Holy Virgin Church (ruins).

Avzaghgpur (Khantrisi)

Saint Kevork Church (built of wood). Serving clergyman: Father Kristapor.

Avzahgpur (Choukhouri)

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in antiquity, renovated in 1871); 2) Holy site of Saint Hagop (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Khachadour Hagopian.

Avzoud

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of wood in antiquity); 2) Holy Zion Church (built of stone in antiquity); 3) Holy Virgin pilgrimage site (ruins). The village was served by a visiting clergyman from the nearby village of Vartenis.

Avran

Places of worship: 1) Saint Hovhanness Church (built of stone, renovated in 1887); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Chapel (built of stone); 3) Saint Sarkis Chapel; 4) Saint Daniel Chapel (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Israel Mejigian and Father Dzaghig.

Arak

Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone circa 1682).

Arkavank

Places of worship: 1) Saint Thomas the Apostle Church (built in antiquity); 2) Holy Virgin Church, also known as Sheg Avedaran (built of wood in antiquity). Serving clergyman: Father Bartev (who also served the village of Arak).

Ardert

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of wood in 1878); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins, with khachkars (stone stelae bearing crosses and other religious motifs) in the old cemetery); 3) Saint Krikor the Hermit Church (ruins); 4) Holy Cross Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Hovsep Tavitian and Father Hovsep Krikorian.

Ardkhonk

Saint Harutyun Church (built of wood; renovated).

Ardonk

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in antiquity); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins), and many khackars and holy sites. Serving clergymen: Father Kasbar, Father Hovhanness Der-Honvhannissian, Father Gabriel, Father Serovpe Der-Kasbarian, Father Moushegh Donabedian, and Father Khachadour.

Pazou

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood, renovated in 1877); 2) Unnamed church (ruins).

Paghlou (Melik)

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of stone, circa 940); 2) Holy Archangels Church (built of wood circa 1854); 3) Saint Kevork Church (ruins); 4) Holy Cross Shrine (ruins); 5) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Garabed Keorkian.

Pklits

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church (built of wood, circa 1136); 2) Saint Khachoug Church (ruins).

Pertag

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of wood; renovated circa 1515); 2) Holy Virgin Church (built of stone in 1330); 3) The Saint Giragos Monastery (also a pilgrimage site; ruins); 4) Saint Minas Church (ruins); 5) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Giragos Markarian and Father Housig.

Plel

The Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone). Serving clergyman: Father Khachadour.

Pntekhner

Unnamed church (ruins).

Posdakent

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (altar, arch, and columns built of stone; façade built of wood; renovated in 1882); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed chapel (ruins).

Karni

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church; 2) Unnamed monastery (ruins); 3) Unnamed monastery (ruins); 4) Unnamed monastery (ruins).

Kelikouzan

Places of worship: 1) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (partially built of wood); 2) Saint Sarkis Church (also a pilgrimage site; ruins); 3) Saint Giragos Church (ruins); 4) Saint Garabed Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Toros Muratian and Father Arakel Der-Kachian.

Komer

Karasoun Manoug (Forty Martyrs) Church (built of wood; renovated). Serving clergymen: Father Sarkis, Father Khachadour, and Father Daniel.

Koms

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (partially built of wood; renovated in the 1870s); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Mampre Yeranosian.

Terig (Ashdishad)

Places of worship: 1) Terig Monastery or the Saint Sahag Church (the main chapel of Ashdishad Monastery); 2) The graves of Saint Sahag and Saint Shushanig; 3) Church of Ekhdatsorig (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Sahag.

An Armenian Protestant family in Moush. The two men seated in the center, from left to right: Reverrend Mihran K. Hagopian (The Protestant priest in the village of Havadorig), Kapriel H. Kaprielian (the director of the German orphanage in Moush) (Source: Sarkis Pteyan and Missag Pteyan, Harazad Badmutyun Daroni (The Authentic Story of Daron), Cairo, 1962)

Tertevank

Places of worship: 1) Saint Toros Church (built of stone circa 1136); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins), 4) Protestant church. Serving apostolic clergyman: Father Movses Ghazarian. Serving protestant minister: Pastor Smpad Khachigian.

Tvnig

Places of worship: 1) Saint Simeon Church (built of wood in 1189; renovated in 1862); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins); 3) Saint Kayane Church (ruins); 4) Unnamed church (ruins); 5) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Movses.

Trmed

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Mikayel and Father Daniel.

Yereshder

Places of worship: 1) Saint Thomas the Apostle Church (built of wood in antiquity, renovated in 1677); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Saint Garabed Monastery (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Garabed Haroyan and Father Harutyun.

Yerizag (Yeritsoug)

Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in antiquity; renovated). Serving clergyman: Father Serovpe Hovagimian.

Ziyaret

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (partially built of wood; renovated in 1851); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Chapel (built of wood); 3) Garmir Avedaran (Red Bible) holy site (ruins); 4) Grave of Saint Toros (holy site; ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Partoghomeos Noradougian, Father Tateos, Father Madteos, and Father Hamazasb Der-Hamazasbian.

Til

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in 1355; renovated in 1890); 2) Unnamed monastery (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins).

Khashkhaltagh

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Khachadour Harutyunian.

Khaskugh

Places of worship: 1) Holy Trinity Church (built of polished stone; rebuilt in 1887); 2) Saint Sdepanos Church (built in antiquity); 3) Saint Tolileos Church (built in antiquity); 4) Holt Virgin Church (ruins); 5) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins); 6) Unnamed church (ruins); 7) Unnamed church (ruins); 8) Unnamed church (ruins); 9) Unnamed chapel (ruins); 10) Unnamed chapel (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Avedis Terzian, Father Khachadour Mouratian, and Father Kerovpe Der-Seropian.

Khartots (Kharapa Khartos)

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone in 1738); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed monastery (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Sarkis Ayvazian and Father Sarkis Mardirosian.

Khars (Kharts, Gharts)

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in 1792); 2) Saint Sarkis (built of stone; in partial ruins); 3) Saint Hagop Church (ruins); 4) Holy Virgin Church (ruins, built in antiquity). Serving clergymen: Father Harutyun Miroyan, Father Hovhanness Ponashentsi, and Father Hovasap Der-Hovhannissian.

Kheypian

Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in 1751). Serving clergymen: Father Garabed Hndian.

Khoronk

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of stone; renovated in 1629); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins).

Khoper

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (renovated circa 1752); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Unnamed church (ruins); 5) Unnamed church (ruins).

Khvner

Holy Virgin Church.

Dzghag

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sdepanos Church (built in antiquity; renovated); 2) Saint Sdepanos Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Unnamed church (ruins); 5) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Avedis Der-Mikayelian.

Dzrked

Unnamed church.

Gemig

Places of worship: 1) Saint Harutyun Church (built of stone; also a pilgrimage site; partially in ruins); 2) Unnamed church (ruins).

Gzlaghach

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church (built of wood, renovated); 2) Saint Hagop Chapel (built of wood). Serving clergyman: Father Moushegh Der-Madteosian.

Gvars

Holy Virgin Church (built of wood; renovated in 1882). Serving clergyman: Father Vaghinag Bahlouni.

Gouravou (Gouravi)

Places of worship: 1) Saint Hagop Church; 2) Holy Book (Holy Virgin) Church. Serving clergymen: Father Garabed, Father Krikor, Father Hagop Der-Seropian, and Father Khachadour Der-Seropian.

Hasanova

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church (renovated in 1874); 2) Saint Shmavon Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Unnamed chapel.

Havadorig

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church; 2) Saint Khachoug Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Protestant church, alongside its adjacent school (renovated).

Hatsig

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood); 2) Saint Merob Mashdots Chapel (built in 1349, in ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins; possibly Saint Hagop Church, built in 1349.)

Hergerd (Hygerd)

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone in 1039); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Saint Toukhmanoug Church. Serving clergyman: Father Markar Danielian.

Hounan

Places of worship: 1) Saint Thomas the Apostle Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Saint Ghazar Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Pastor Hrair Hlzadian (serving the Protestant community).

Tsapna (Dzapna)

Saint Kevork Church (built in 1330).

Tskhavou (Dzkhavou, Tskhavi)

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of wood; renovated in the 1850s). Serving clergymen: Father Hovhanness and Father Avedis Vartanian.

Marnig

Places of worship: 1) Unnamed church (ruins); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Saint Garmir Monastery (ruins).

Meghti

Saint Miantsoung Church (chapel built of stone; the altar built of wood in antiquity).

Mgrakom

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Unnamed church (ruins).

Mogounk

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sdepanos Church (built of wood; in a dilapidated state); 2) Holy Savior Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins); 5) Unnamed church (ruins); 6) Saint Kasbar Church (built of stone, in a dilapidated state); 7) Protestant church.

Norshen (Armenian Catholic Village)

Places of Worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church; 2) Saint Sophia Church (partially in ruins).

Sheykhalan

Places of worship: 1) Unnamed church; 2) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Nerses Der-Mgrdchian and Father Zaven.

Sheykh Yousouf

Holy Virgin Church (built in antiquity). Serving clergyman: Father Arakel.

Sheykhprim

Places of worship: 1) Unnamed church (ruins); 2) Unnamed chapel. Serving clergymen: Father Khachadour Der-Markarian and Father Israel Padigian.

Shenig

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood; renovated); 2) Saint Kevork Church (renovated); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Saint Mariam Church (ruins); 5) Saint Teotoros Church (built of stone; in a dilapidated state). Serving clergyman: Father Boghos Vartanian.

Shemlag

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Saint Garabed Church (built in antiquity; in ruins).

Chrig

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (build of wood; chapel built of stone); 2) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Bishop Moushegh Der-Partoghomeos Yeretsian and Father Vaghinag.

Sahag

Unnamed church (built in antiquity; partially in ruins).

Semal

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church (built of stone; renovated); 2) Saint Hripsime Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Dzidzernagavank Monastery (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Garabed Boghosian.

Antsnoud

Holy Virgin Church (built of wood in antiquity).

Sokhkom

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sahag Church (built of wood circa 1515); 2) Noreloug Church (built of wood); 3) Saint Shamamig Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Krikor and Father Hrair Soukiasian.

Sortar

Holy Virgin Church (ruins/partially collapsed). Serving clergyman: Father Smpad Bahlouni.

Souloukh

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of stone; renovated in 1885); 2) Saint Kevork Church (built of stone; also a pilgrimage site); 3) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Garabed and Father Sdepan Ghazarian.

Vartenis

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Saint Hagop Church (built in antiquity; in ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Khachadour Melkonian and Father Harutyun Paghtasarian.

Vartkhagh

Places of worship: 1) Unnamed church (within the village; in ruins); 2) Unnamed church (north of the village; in ruins); 3) Unnamed church (east of the village; in ruins).

Dadrakom

Places of worship: 1) Unnamed church (within the village; in ruins); 2) Unnamed church (north of the village; in ruins); 3) Unnamed church (north of the village; in ruins).

Dom

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (built of wood; renovated); 2) Saint Simeon Church (built of stone circa 1807); 3) Saint Sdepanos Church (ruins).

Tsronk

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of stone in 1151; renovated circa 1678); 2) Saint Hagop Church (built in 1151; renovated in 1664); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Saint Kevork of the Mountain Church (ruins). Serving clergymen: Father Moushegh Mikayelian, Father Hovhanness Der-Hovhannissian, and Father Nerses Asdvadzadourian.

Oushdam

Holy Virgin Church. Serving clergyman: Father Simon Der-Hovhannissian.

Ourough

Places of worship: 1) Saint Sarkis Church (built of wood); 2) Saint Sarkis Church (ruins); 3) Garmir (Red) Church (ruins); 4) Unnamed chapel (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Mgrditch Der-Mgrdchian.

Petar (Pitar)

Places of worship: 1) Saint Hagop Church (built of wood); 2) Saint Garabed Church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins).

Poghegov

Places of worship: 1) Saint Kevork Church (built of stone in antiquity); 2) Unnamed church (east of the village; in ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Parsegh Der-Parseghian.

Kartsor

Places of worship: 1) Saint Minas Church (built of wood); 2) Saint Toros Church (ruins); 3) Saint Toukhmanoug Church (ruins).

Kolosig

Places of worship: 1) Saint Hagop Church (in ruins; built in antiquity); 2) Unnamed church (ruins); 3) Unnamed church (ruins); 4) Unnamed church (ruins).

Krtakom

Places of worship: 1) Holy Virgin Church (renovated in 1700); 2) Toukhmanoug Holy Site; 3) Unnamed church (ruins). Serving clergyman: Father Garabed Parseghian.

Kourtmeydan

Unnamed church.

Oghounk (Armenian Catholic Village)

Saint Minas Church. Serving clergyman: Father Mgrditch Der-Mgrdchian.

Orknots (Horgnots)

The Holy Virgin Church (built of wood, in antiquity). Serving clergyman: Father Krikor.

Monasteries of the Moush Valley

Garo Sassouni, in his work Badmtyun Daroni Akhskhari (History of the Land of Daron), mentions the names of fifteen historical Armenian monasteries scattered across the Moush Valley [28]. By the second half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, only three of them were still functioning as monasteries – the Saint Garabed Monastery (Klaga), the Sourp Arakelots (Holy Apostles) Monastery (Tarkmantchats Monastery), and the Saint Hovhanness Monastery (Yerghrtoud).

Other historically significant monasteries included the Madravank and Saint Sahag (Ashdishad) monasteries, but by the late 1800s/early 1900s, they had fallen into disrepair and were in a dilapidated state.

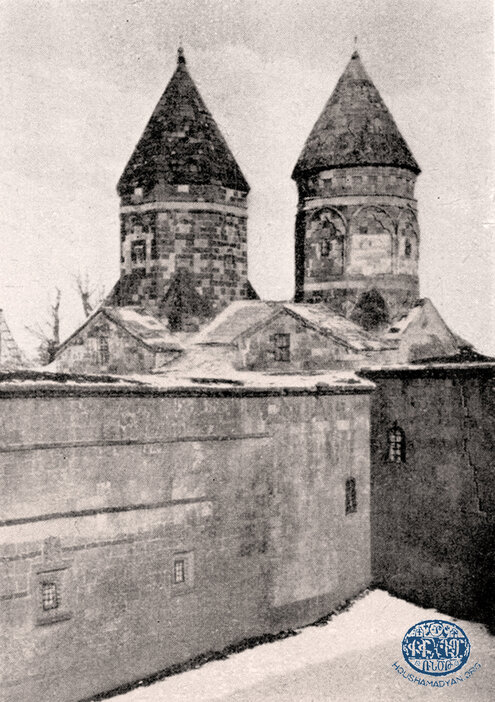

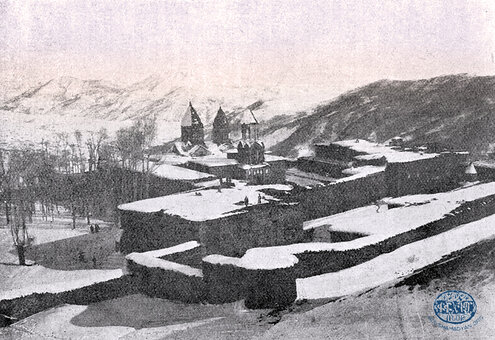

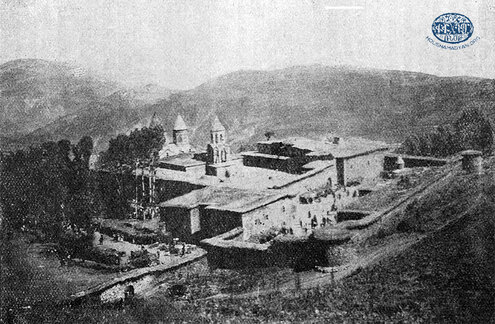

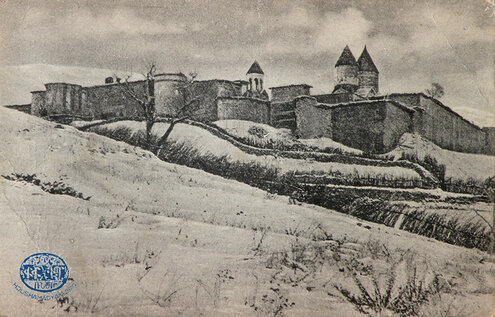

The Saint Garabed (Hovannou-Garabed) [John the Baptist] Monastery

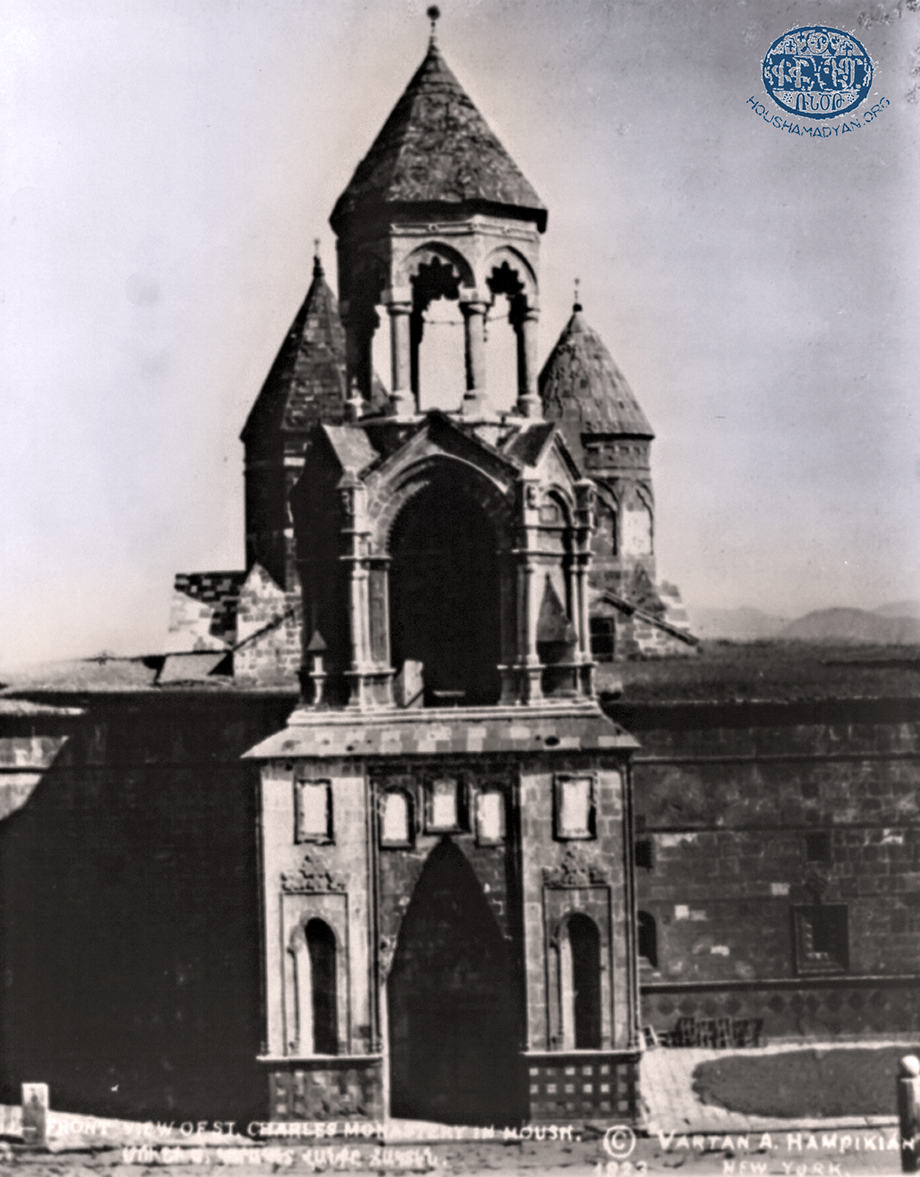

Saint Garabed was one of the most well-known monasteries of Moush and Armenia. It was founded in the fourth century by Saint Gregory the Illuminator, on the flanks of a mountain then named Havadamk. The monastery has been known by many names, including Klaga Monastery (in honor of Zenop Klaga, the first abbot of the monastery), and Innangian Monastery (a reference to the many fresh-water springs that dotted the land around the monastery). The cathedral of the monastery was beautiful, crowned by its three magnificent steeples. For this reason, the area’s Turkish and Kurdish population called the area around the monastery Chanle Kilise, meaning “steepled church.” [29]

The monastery’s oldest shrine, the Saint Garabed Chapel/Martyrium, was a steepled hall. In an alcove in the western corner in the building rested the relics of Saint Hovhanness Garabed [John the Baptist], and in an alcove in the southwest corner the relics of Archbishop Atanakine [Saint Athenogenes]. Across the main altar were four khachkars engraved into the wall, bearing the date 1718. Saint Gregory the Illuminator’s monastic cell was located in the northern end of the complex, adjacent to the domed Saint Kevork Chapel. On the other side of the compound were the steepled Saint Sdepanos Chapel (with a cross-shaped design inside, and a triangular shape on the outside), and the large, domed Holy Virgin Church [30].

All four of the above-mentioned chapels opened onto by the monastery’s main cathedral, which was a square-shaped basilica supported by 16 columns and featuring five naves. The central nave ended in the east with the main altar, while two other naves ended with transepts, the one in the northern corner dedicated to St. James [James the Just, or James, the Brother of the Lord], and the one in the southern corner dedicated to Saint Gregory the Illuminator. Outside of the western entrance of the cathedral were three steps, leading to an altar dedicated to the Holy Spirit, and an eight-columned, steep belfry (built in 1787) [31].

The monastery was surrounded by fortress walls, built using a triangular structure. Adjacent to the wall were two-story residential and commercial buildings, separated by a wall from the cells housing pilgrims [32].

Contemporaries often described the monastery compound as awe-inspiring, and mentioned that the area had clean air and plenty of clean water [33]. Near the monastery’s walls flowed the Saint Gregory the Illuminator Spring. According to legend, the square-shaped pool of the spring was built by Tiridates (Drtad) The Great (Tiridates III), and was used by Gregory the Illuminator for many baptisms [34].

The monastery was renovated in 1900-1902 [35]. In the second half of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, the monastery owned many properties and estates, fields and orchards, and farms with fertile land. The monastery generated considerable income, alongside the donations and tithes it received from the villagers [36].

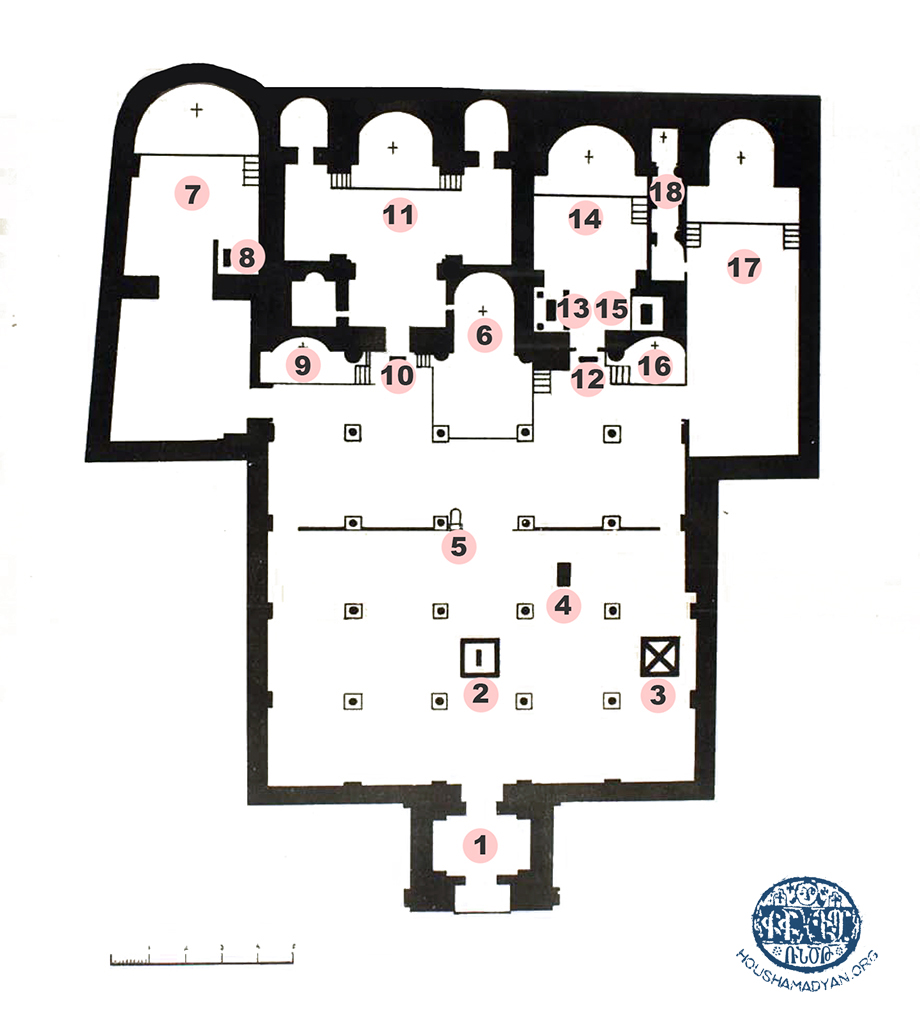

The plan of the main Church in Saint Garabed Monastery

1 The bell tower | 2 The grave of the prince Tornig of Sasoun | 3 The grave of the Mamigonian family| 4 The grave of Moushegh Mamigonian | 5 The Seat of the Prior | 6 The High Alter, Holy Cross (Sourp Khach)| 7 The Holy Mother of God Church (Sourp Asdvadzadzin) chapel| 8 The grave of Stepanos (Vart Badrig’s son)| 9 The altar of St Hagop | 10 The grave of Smpad Mamigonian | 11 The chapel of St Stepanos | 12 The grave of Kayl Vahan | 13 The tombstone (relic) of St John Baptist (Hovhannou Mgrditch)| 14 The chapel of St Garabed | 15 The grave of the Bishop Atanagin

16 The altar of St Krikor the Illuminator | 17 The chapel of St Kevork | 18 The hermitage || Drawing by Father S. Asdvadzadourian

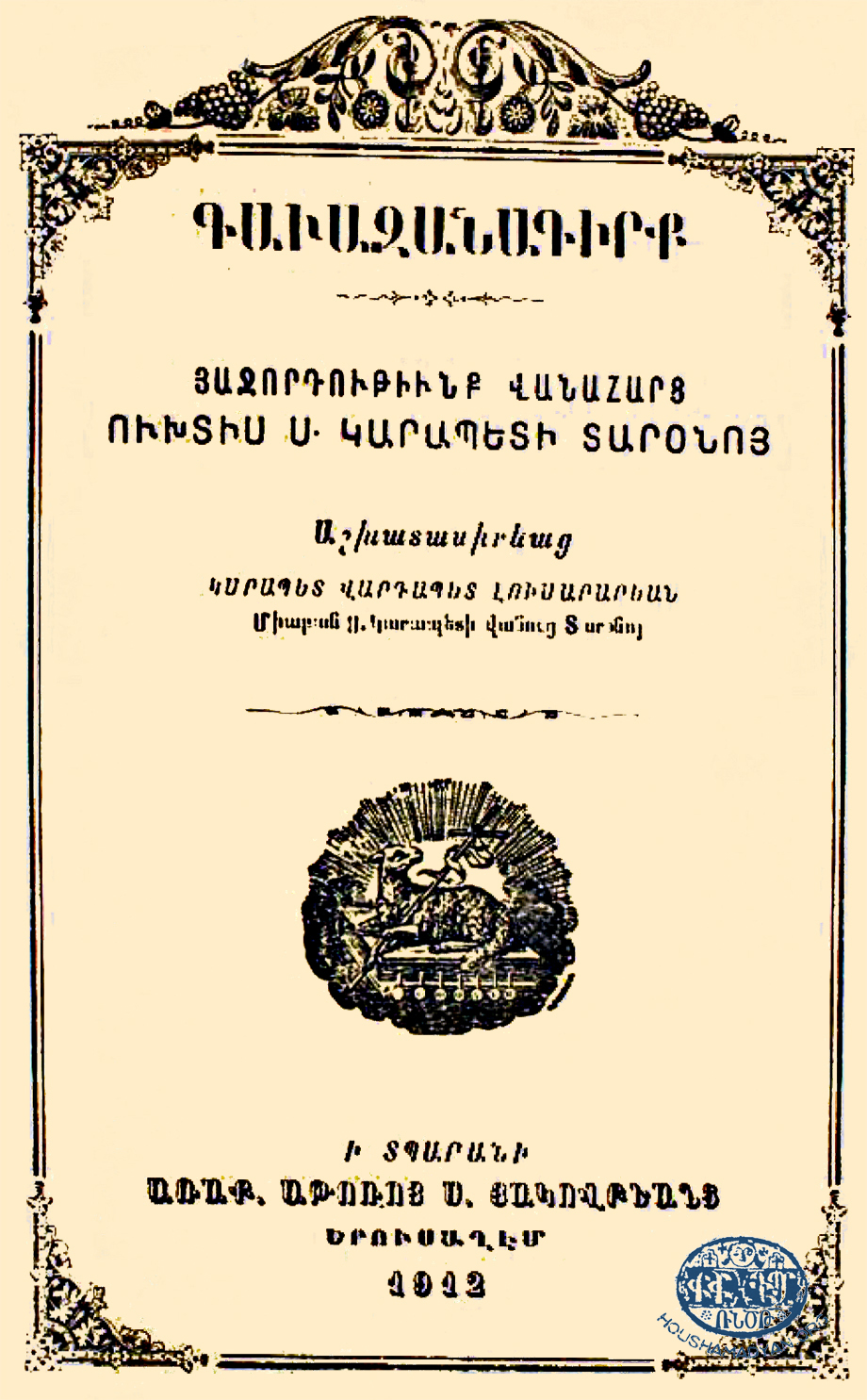

(Source: Garabed Lousararian, Kavazanakirk: Hachortoutyunk Vanaharts Oukhdis S. Garabedi Darono, Jerusalem, published by the S. Hagopyants Apostolic Diocese, 1912)

The monastery was a literary, educational, and cultural center, and had a large library. It was the second most important religious site in Armenia, after Echmiadzin. It was known as “the capital of cloisters,” and it was a popular pilgrimage site, to Eastern Armenians as well as Western Armenians. The principal days of pilgrimage were the day of Vartavar and the day of the Feast of Assumption. On those days, the monastery would also host feasts, festivals, and markets. A pilgrimage to the monastery was thought to grant wishes, cure illnesses, and bestow special talents (including artistic). The area’s canon of folk music includes many songs celebrating pilgrimages to the monastery [37].

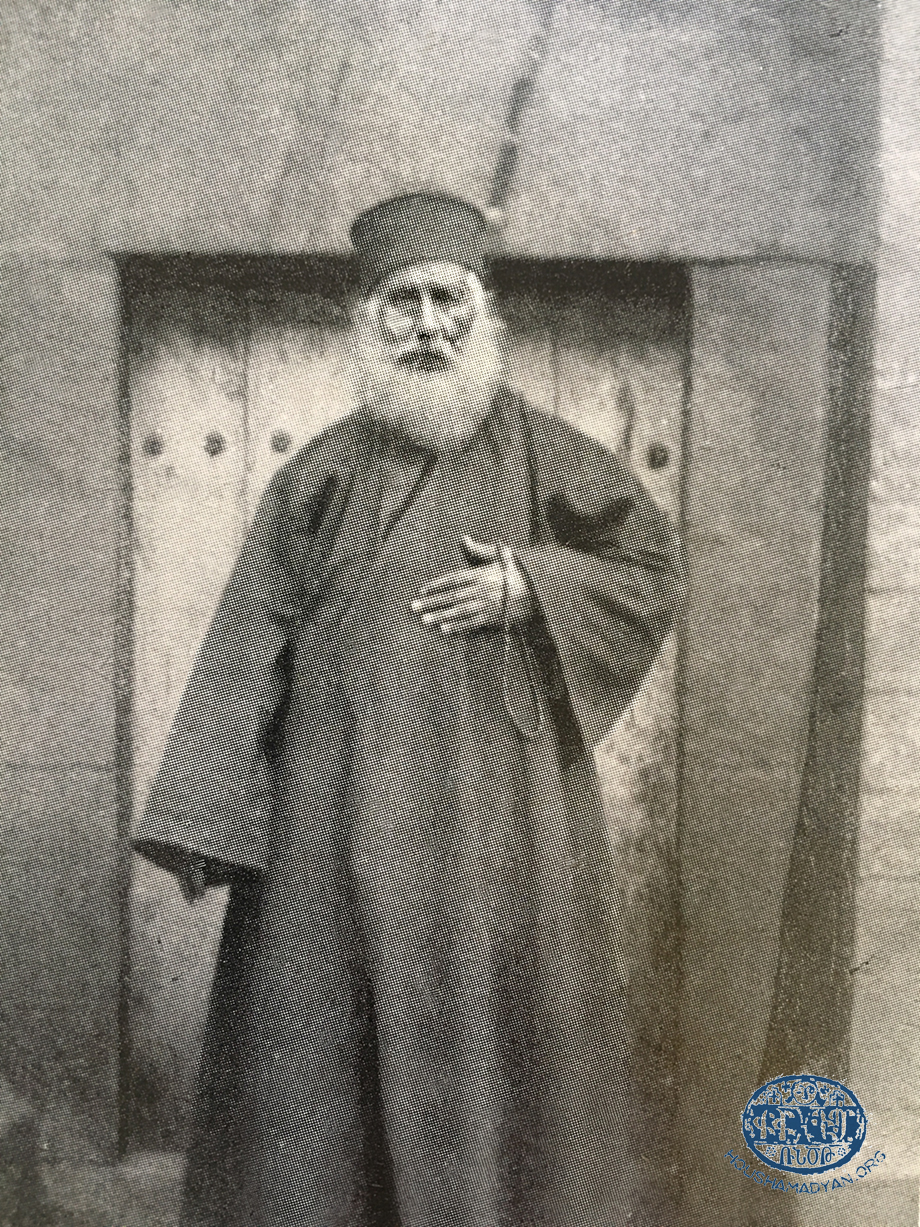

The Saint Garabed Monastery was the seat of the Daron-Darouperan See, one of the more important and influential dioceses in Ottoman Armenia. The abbot of Saint Garabed was also the prelate of the diocese [38]. From 1862 to 1869, the abbot of the monastery was Mgrdich Hayrig Khrimian [39]. In 1869, when Khrimian became the Patriarch of Istanbul, he was succeeded by Karekin Srvantsdyants, who remained at the position until 1873. In 1888, Srvantsdyants was appointed as abbot and prelate again, but he did not serve in that capacity for long. Soon, the authorities ordered him back to Istanbul to answer trumped-up charges against him [40].

The last abbot of the monastery, and thus the last prelate of Moush, was Bishop Nerses Kharakanian (who died on April 12, 1915) [41]. On the eve of the genocide, the Saint Garabed Monastery’s clergy included six priests: Father Yeghishe Balouni, Father Garabed Ardzrouni, Father Yeghishe Garabedian (senior priest), Father Vahan Yeretsian, Father Garabed Lousararian, and Father Khachadour Akouletsi [42].

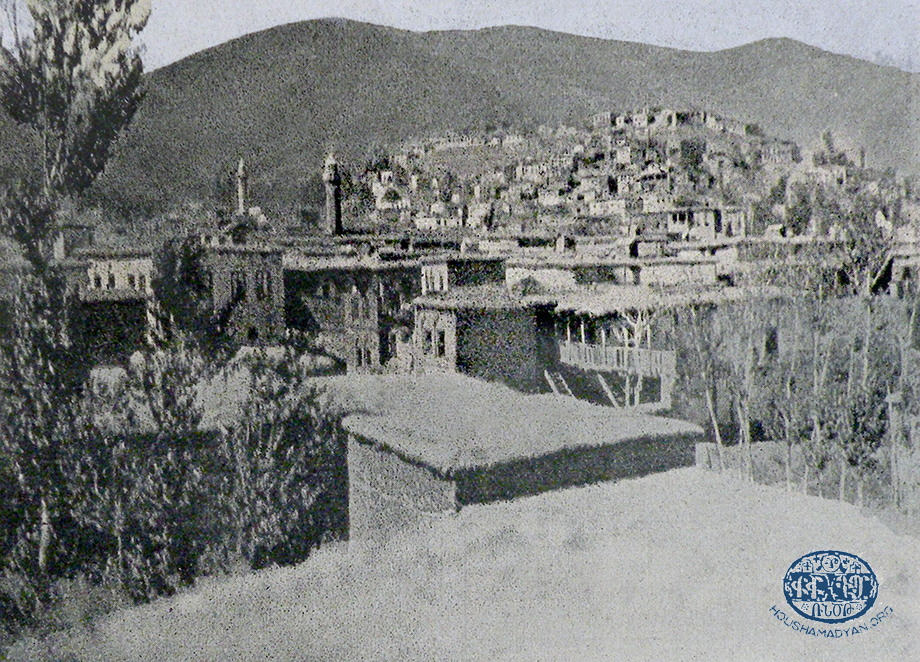

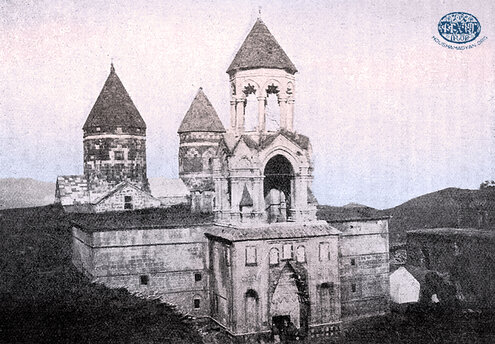

Sourp Arakelots (Holy Apostles) Monastery of Moush

The Holy Apostles Monastery of Moush was located about 10 kilometers southeast of the city, the equivalent of a two-and-a-half hour journey on foot. The monastery was nestled between two summits of the Taurus Mountains, in a scenic setting, on the flanks of a mountain called Dirngadar or Tsirngadar (hence the monastery’s alternative name of Monastery at the summit Areknadzak Dir) [43].

The monastery was also known as Tarkmanchats (Translators’) Monastery, due to the several monastic scribes and translators buried in the cemetery. Yet another alternative name for the monastery was The Monastery of Yeghyazar, which was the name of the monastery’s first abbot [44].

According to tradition, the monastery was founded in 312 by Gregory the Illuminator, who is said to have placed relics from all twelve apostles in the altar [45].

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were two churches in the monastery’s compound. The main church, the Arakelots (Apostles) Church, was built in the 11th century, partly of polished stone, and partly of brick. The interior was cross-shaped, and the exterior was rectangular, with a steeple rising above the church. Inside, on the right and left sides of the structure respectively, were the tombs of the apostles Mark and Luke [46].

Sp. Arakelots Vank (Source: Hamazasb Voskian, The Daron-Douruperan Monasteries [in Armenian], Vienna, Mkhitarian Press, 1953)

In the cemetery of the monastery were buried many celebrated Armenian scribes, including Tavit Anhaght, Ghazar Parbetsi, Mampre Vernadzogh, Asoghig, and Boghos Daronatsi. All of these men had worked in the monastery, where they had written, translated, and otherwise produced many works of Armenian literature.

The main door of the church was made of walnut wood, and has been preserved to this day. It features delicate and tasteful carvings of various images and symbols. The door was installed in the 12th century, as evidenced by the inscription it bears – “In the year MCXXXIV (1134), D. Toros, Krikor, and Ghogas carved this door” [47]. After the start of the First World War, and during the first year of the Armenian Genocide (1915), German officers interested in antiquities, taking advantage of the deportation and massacres of the local Armenian population, received permission from the Ottoman government to remove the door from the monastery, and transported it to Tbilisi. There, they waited for an opportunity to transport it to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin. However, the Russian armies occupied Tbilisi before they had the chance to do so, and the door fell into the hands of Russian soldiers, who in turn handed it over to refugees fleeing to the Caucasus. The latter, recognizing that they were now entrusted with an object of great cultural value, diligently brought it with them to the Caucasus. The door is currently on display in the History Museum of Armenia [48].

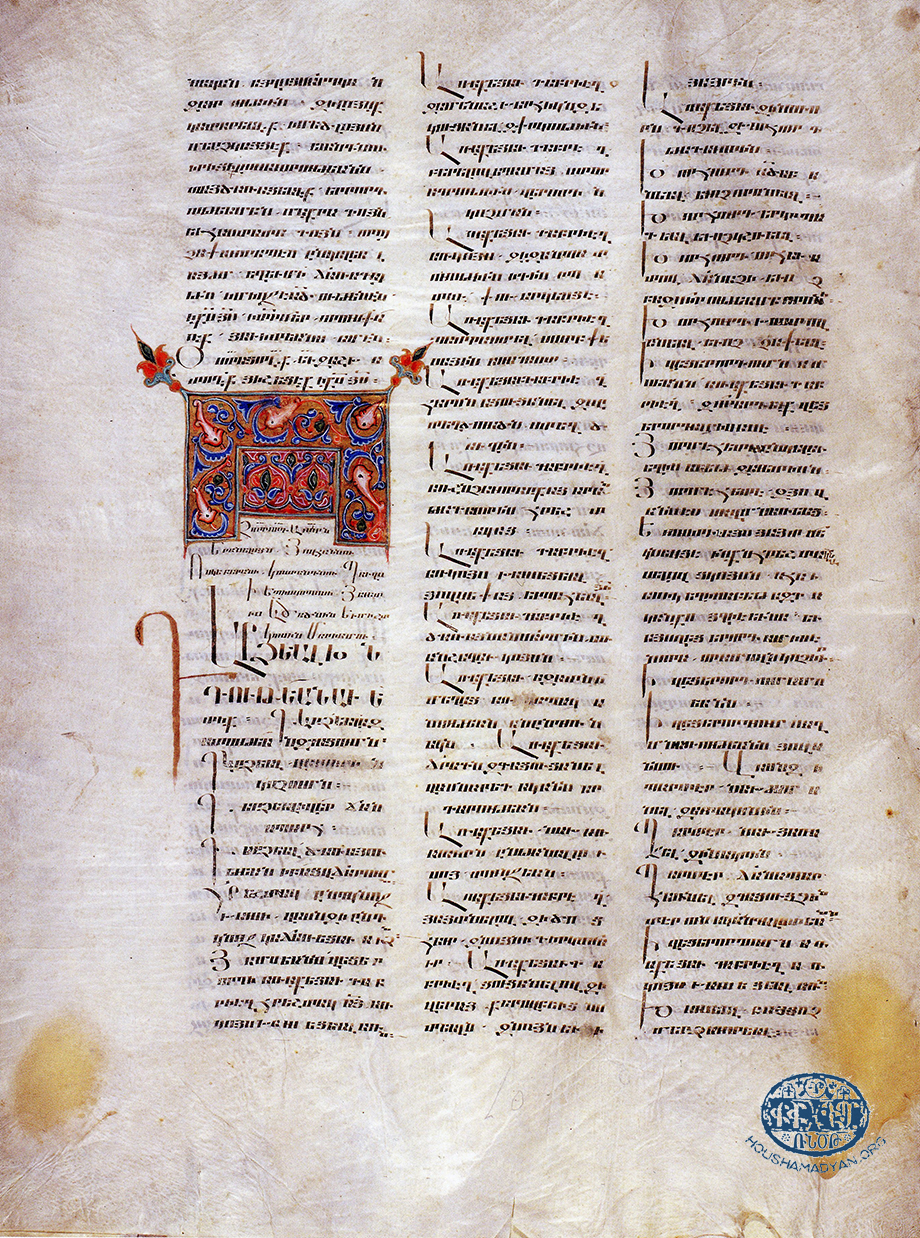

Until 1915, the monastery was also home to longest Armenian hand-written manuscript on parchment, the Msho Jarendir, which was written and illustrated between 1200 and 1202. As soon as the manuscript was finished, it was confiscated by the non-Armenian magistrate of Bayburt, who kept it for two years, then, in 1204, sold it to the monastery for 4,000 silver coins, which had to be raised from the by the people and the monks of the monastery. During the days of the Armenian Genocide, the manuscript was split into two halves, and these two halves made their way separately to the Armenian Ethnographic Society in Tbilisi, and from there to Yerevan. Today, the Msho Jarendir is kept at the Mesrob Masdhots Repository of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan (Matenadaran) [49].

On the eve of the genocide, the abbot of the monastery was Bishop Hovhanness Mouratian [50].

Saint Hovhanness Monastery of Yeghrtoud

The Saint Hovhanness Monastery of Yeghrtoud (also known as the Ardzvaper Monastery and the Shishyugho Monastery), was located deep in the Moush Valley, at a distance of about 20-22 kilometers southwest of the city, at the foot of Sevsar (Sim Mountains). The monastery was located near the village of Yeghrtoud, in a beautiful, scenic area [51]. The location and surroundings of the monastery were described by Archbishop Drtad Balian in his book Hye Vanorayk (Armenian Clergy): “The monastery was built of stone, surrounded on all four sides by forests and natural springs, and blessed with pure air. From the monastery one had a panoramic view of the Moush Valley, which spread in all directions like a sea of green. The Sipan and Khoyl Baba mountains are visible in the distance.” [52]

The monastery was founded in the fourth century, during the days of Saint Gregory the Illuminator and Patriarch Vrtanes [53]. There are many legends linked to the monastery and the etymology of its many names. According to one, the monastery contains the relics of John the Baptist, and that is why the monastery is named after him. According to another legend, Jude the Apostle (Thaddeus) had brought to the monastery a vile of the oil with which Mary Magdalene had anointed Christ, and with which Christ had then anointed his disciples. The monastery’s alternative name of Shishyugho [vile of oil] is thought to have originated with this legend [54]. According to yet another legend, Jude’s vile of oil was kept underneath a tree named Yeghrtoud, and for that reason the site was called the Yeghrtoud Monastery [55].

The principal chapel of the monastery was almost the equal of the cathedral of the Saint Garabed Monastery in size and height. It was built using polished stone, and had an oval shape [56]. The walls and the monastery’s outer walls had sustained damage over the years from the earthquakes that struck the region [57].

Saint Hovhanness Monastery of Yeghrtoud (Source: Hagop Mandjigian, Memorial book of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, an album-atlas, Vol. 1, Los Angeles, 1992)

The monastery’s belfry was of medium height, and had been built in 1828. Inside and outside the chapel were many fonts, chapels, and other structures dedicated to St. Athenogenes, the Holy Virgin, Saint Kevork, and Saint Sarkis [58].

Near the other chapel of the monastery (Saint Sdepanos), there was a cemetery, where many of the renowned clergymen who had lived in the monastery were buried. The compound also featured an administrative building and more than 30 monastic cells. In the early 20th century the monastery owned large fields, farmland, and forests [59].

Pilgrims came to the monastery on the Day of Vartavar, the Feast of Ascension of Mary, and on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross [60].

One the eve of the genocide, the abbot of the monastery was Father Mgrdich Kasbarian (born in 1845, ordained in 1884, and killed during the genocide) [61].

Madnavank

Madnavank (also known as Madravank, Manravank, and Markarianots) was located about four hours’ distance (20 kilometers) north-west of the City of Moush, across from the Village of Dzghavou, on the banks of a small tributary of the Aradzani River. According to tradition, the monastery was founded by Gregory the Illuminator, who is also said to have placed several small bones of Saint Garabed, which he had brought from Gesaria (Kayseri), in the monastery, from which the monastery had obtained its name [62]. Other explanations of the name include the small size of the altar, the fact that people pointed out the monastery with their fingers, and other theories [63].

By the end of the 19th century the monastery was abandoned, and there were no serving clergymen there, but it remained a popular pilgrimage site for the people. The monastery’s principal chapel, built of stone, was in complete ruins. Bishop Drtad Balian provides the following description of the monastery: “The chapel of the monastery was an example of medieval architecture, with its domes and narrow windows. The chapel was divided into three sections – the nave, the altar, and the shrine. Rising above the roof of the nave was a belfry built of polished, white stone, crowed by a cross that bore the inscription This cross stands to praise the Lord and beseech His grace upon the souls of Khalfa Yeghya and his parents, in the year MDCCXXXVII (1737). The chapel was small and dark, and there was no table of the altar, only two tables, one on the right, and one to the left. Halfway between these tables was a door leading to the shrine, where there were two graves, one bearing the name of Saint John the Baptist, the other bearing the name of Saint Athenogenes. This shrine was the oldest part of the chapel, and the ceiling was quite high, without supporting columns. The chapel and the domes have been kept in their original forms. Near the windows of the altar and the shrine can be found the following inscriptions: In the year MDXLIV (1544) – Once again this church has been rebuilt by Father Toros, in memory of his parents, and In the year MDC (1600) – Once again this church has been rebuilt by Father Hovhanness, in memory of his parents, and with the aid of Khoja Sheykh and his father Zazri , who spared no efforts in carrying and planing the timber [64].”

The monastery only had two or three habitable rooms. Its parish included the villages of Avran, Gouravou, Tskhavou, Salorig, Terig, Akhjag, Ardert, Alijan, and Sheykh Yusuf. The monastery owned arable and fertile lands and pastures [65].

The Saint Sahag Bartev Monastery (Ashdishad Monastery)

The Saint Sahag Bartev Monastery was located near the town of Ashdishad, which was an important religious site during pagan times, and had also been an important religious center after Armenia’s conversion to Christianity. By the early 20th century, the site of historic Ashdishad was occupied by the Armenian village of Tereg. From the monastery’s hill, one had a breathtaking view of the Moush Valley, and could also see the Aradzani and Meghraked rivers.

According to tradition, the monastery was founded by Gregory the Illuminator. By the second half the 19th century and early 20th century the monastery was derelict and in ruins.

According to an observation published in 1897, “today, the monastery betrays no signs of its former glory. At the site, all that can be found is remains of chapels and the ruins of a large church ( . . . ) The walls and the structures have been almost completely razed to the ground. The church was exactly 38 feet long and 14 feet wide. The cement walls were 8 feet deep.”[66]

Bishop Drtad Balian, in his book Hye Vanorayk (Armenian Monasteries), describes the ruins of the Saint Sahag Bartev Monastery thus: “The stones that made up the walls are scattered, and where the old church used to stand, or rather right beside its original location, there is a small wooden chapel. In a cellar underneath the chapel is the tomb of Saint Sahag, after whom the monastery is named, in honor of his great stature and works. Beside Saint Sahag lies Saint Shoushan in her own tomb, alongside two other tombs. ( . . . ) In the center of the ruined church are three altars and three columns, still barely standing, forming the three corners of a triangle, and evoking the original structure of the church in its heyday. There are also traces of the main door and nearby chapels. According to the tradition, the southernmost chapel (of the three mentioned previously) was called The Altar of the Chrism. On this altar is engraved the name of another monastery, named Ashdits, which remains unknown to me. ( . . . ) Legend also holds that near this main church there once was a steeple, atop which was a large cross. To this day, a khachkar stands beside the baptismal font. This khachkar was held in high esteem by the people, and was often called Krdinki Khachkar (the khachkar of perspiration). It is said that the date MDLXXXI (1581) is engraved on the khachkar.” [67]

Other Derelict Monasteries of the City of Moush and the Moush Valley

-Arkavank: Located near the eponymous village.

-Saint Arisdages Monastery: Located at a distance of two kilometers from the Village of Tel.

-Kasbar Monastery: Near the Village of Mogounk.

-Saint Kevork: Near the Village of Abelbahar (Apelpuhar).

-Saint Kevork: Near the Village of Paghlou.

-Saint Kevork: Near the Village of Souloukh.

-Saint Garabed Monastery: Near the village of Pertag, and a very popular pilgrimage site with the people of the nearby villages.

-Saint Mesrob Monastery: Near the Village of Hatsig, the birthplace of Mesrob Mashdots. By the late 19th century and early 20th century, all that was left of the monastery was a small martyrium dedicated to Mesrob Mashdots.

-Monastery of Holy Zion: Near the Village of Avzoud, at the foot of Mount Krkour. By the late 19th century and early 20th century, all that was left of the monastery was a single chapel, which had become a pilgrimage site or the people of the nearby villages [68].

- [1] Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la Veille du Génocide (Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide), Paris, ARHIS, 1992, page 479.

- [2] Sarkis Pteyan and Missag Pteyan, Harazad Badmutyun Daroni (The Authentic Story of Daron), Cairo, published by the Armenian National Fund, 1962, page 90.

- [3] According to facts provided by Nazaret Mardirosian, secretary of the Armenian Apostolic Church Prelacy in Moush (Van-Dosb political, literary, and society weekly magazine, Tbilisi, Year 1, N. 12, February 4, 1916, page 8).

- [4] Ibid.

- [5] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian Churches and Monasteries in the Ottoman Empire Presented to the Ottoman Ministry of Justice and Religious Minorities by the Armenian Patriarchate in Istanbul”, published in Echmiadzin, the official publication of the Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church of Echmiadzin, 1965, B-C-D, page 183.

- [6] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin (The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915), Tehran, 2014, page 107.

- [7] Van-Dosb… No. 12, February 14, 1916, page 8.

- [8] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian churches…”, page 183.

- [9] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 107.

- [10] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian churches…”, page 183.

- [11] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 107.

- [12] Van-Dosb… No. 12, February 14, 1916, page 8.

- [13] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian churches…”, page 183.

- [14] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 107-108.

- [15] Van-Dosb… No. 12, February 14, 1916, page 8.

- [16] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian churches…”, page 183.

- [17] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 108.

- [18] Van-Dosb… No. 12, February 14, 1916, page 8.

- [19] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian churches…”, page 183.

- [20] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 108.

- [21] Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri Deghannounneri Pararan (Dictionary of Place Names in Armenia and the Environs), volume 3, G-N, Yerevan, Yerevan State University, 1991, page 893.

- [22] In 852, Khoutetsi Hovnan and his comrades-in-arms killed Yusuf, the leader of Arab hordes, in the courtyard of the Holy Savior Church.

- [23] Luma Literary, Political, Historical, and Social Periodical, Tbilisi, 1899, Book A, page 139.

- [24] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 108.

- [25] Nazaret Mardirosian (the secretary of the Moush Prelacy), in the census he conducted, lists the names of 109 Armenian-populated villages (Van-Dosb… No. 12, 1916, pages 8-9). Teotig, using information from the Armenian Prelacy’s 1913-1914 census, lists the names of 101 Armenian settlements (Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 110-125).

- [26] Kevorkian/Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman…, page 487.

- [27] 1878 data: Arisdages Devgants, Aytseloutyun I Hayasdan 1878 (Visit to Armenia in 1878), Yerevan, Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic – Academy of Sciences, 1985, pages 48-54. 1902 data: Survey of Schools, Churches, Martyriums, Chapels (both standings and in ruins, in the area of the Moush Valley), Holy Sites, Settlements, and Ecclesiastical Servants, Conducted Upon the Request of the National Patriarchate, 1902, Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), personal journals of Kegham Der-Garabedian (Dadrag) (the document was provided to us by Houshamadyan). Also refer to the Houshamadyan article Moush – Demography, by George Aghjayan (http://www.houshamadyan.org/arm/mapottomanempire/bitlispagheshvilayet/kazaofmush/mushlocale/mushdemography.html). 1913-1914 data: Kevorkian/Paboudjian, Les Armenians dans L’Empire Ottoman, pages 477-490.

- Information regarding the renovations of certain churches was obtained from the list and the data presented in 1913 by the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate to the Ottoman Ministry of Justice and Religious Minorities (A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Lists of and Reports on Armenian churches…”, page 783 (the original source provides the dates according to the Islamic calendar. The conversion to Gregorian dates was performed by the author)). Some of the information was also obtained from Survey of Schools, Churches, Martyriums, Chapels…

- The names of serving clergymen on the eve of the genocide was obtained from Teotig’s Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…

- [28] Garo Sassouni, Badmutyun Daroni Ashkharhi (History of the Land of Daron), Beirut, Sevan Publishing House, 1956, pages 290-291. To that list of monasteries must be added the Mamkoun Monastery, which is mentioned by Bishop Drtad Balian in his book Hye Vanorayk (Bishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk (Armenian Monasteries), Echmiadzin, Publishing House of the Mother See of Echmiadzin, 2008, page 255.)

- [29] Bishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 249.

- [30] Krisdonya Hayasdan (Christian Armenia) Encyclopedia, Yerevan, Armenian Encyclopedia Publishers, 2002, page 755.

- [31] Ibid.

- [32] Ibid.

- [33] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 249.

- [34] Krisdonya Hayasdan Encyclopedia…, page 756.

- [35] Ibid., page 755.

- [36] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 249.

- [37] Krisdonya Hayasdan Encyclopedia…, page 755-756.

- [38] Sassouni, Badmutyun Daroni, page 289.

- [39] Garabed Lousararian, Kavazanakirk: Hachortoutyunk Vanaharts Oukhdis S. Garabedi Darono, Jerusalem, published by the S. Hagopyants Apostolic Diocese, 1912, page 106.

- [40] Ibid., pages 111-113.

- [41] Haygagan Harts Hanrakidaran (Encyclopedia of the Armenian Cause), Yerevan, Haygagan Hanrakidaran Publishers, 1996, pages 165-166.

- [42] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan, pages 110-111.

- [43] Bishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 251; Gamsar Avedisian, Hayrenakidagan Etudner (Studies in Armenology), Yerevan, “Soviet Author” Publishing House, 1979, page 208.

- [44] Ibid.

- [45] Ibid.

- [46] Bishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, pages 251-252.

- [47] Ibid.

- [48] Gamsar Avedisian, Hayrenakidagan Etudner, pages 206-207; Arakel Badrig, “Msho Arakelots Vanke” (“The Holy Apostles Monastery of Moush”), in Echmiadzin, 1952, 9, pages 23-26. Another theory is that the door was transported to Tbilisi by the Turks to be installed in one the mosques there (Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan, page 125).

- [49] Haygagan Sovedagan Hanrakidaran (Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia), Volume 7, Yerevan, HSH Publishers, 1981, page 658.

- [50] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 125.

- [51] Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri Deghannounneri Pararan, Volume 2, D-G, Yerevan, Yerevan State University, 1988, page 193.

- [52] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 251-252.

- [53] Ibid.; Hamazasb Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere (Monasteries of Daron-Darouperan), Vienna, Mkhitarian Publishing House, 1953, page 93.

- [54] Hamazasb Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 94; Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri…, page 194.

- [55] Ibid. Msho Kegham (Kegham Der-Garabedian) provides this vivid description of the tree – “The Yeghrtoud is an evergreen, grows to a medium height. To this day, the tree stands in the east of the monastery, beside the chapel, providing her shade to a spring. The tree was almost the only one of its kind in the area and was carefully tended. It was kept in an enclosed area, protected by fencing and walls, and near its branching roots were bits of old khachkars and the remains of an old chapel. The yeghrtoud was considered sacred, especially by women and girls, and by the sick, who would visit the tree and tie a piece of cloth to its branches, which they believed would ensure that their ailment was left behind also, and they would take home the tree’s green leaves and twigs, believing they had medicinal properties. The evergreen nature of the tree was part of its sacred mystery for the local pilgrims, who were accustomed to finding the touch of the divine in the rustling of leaves, the murmuring of springs, and other natural phenomena on earth and in heaven “ (Hamazasb Vosgian, Daro-Darouperani Vankere, page 96).

- [56] Ibid.

- [57] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 254.

- [58] Ibid.

- [59] Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri…, Volume 2, page 194.

- [60] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 254.

- [61] Teotig, Koghkota Hye Hokevorutyan…, page 113.

- [62] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 255; Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri…, Volume 3, G-N, Yerevan, published by Yerevan State University, 1991, page 715.

- [63] Ibid.

- [64] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hye Vanorayk, page 256.

- [65] Ibid.

- [66] “The Land of Moush,” published in the Luma Literary, Political, Historical, and Social Periodical, Tbilisi, 1897, N. 1, page 144.

- [67] Ibid., pages 257-258.

- [68] Sassouni, Badmutyun Daroni…, pages 290-291.