Musa Ler - Religious customs

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 18/06/15 (Last modified 18/06/15)- Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

The family structure in Mousa Ler was patriarchal. Living for centuries according to traditional customs, these mountain folk were shaped with unique characteristics – abstinent but full of life; crude but sincere and compassionate; strict but fun-loving.

Change didn’t come easy for them. One can even say they were intolerant and imprudent. They always stuck to their roots, maintaining their dialect and traditions. They were connected to nature and the native soil. The family was the smallest model of society at large, the village and ones extended kith and kin. Needless to say, families were close knit. Living together under one roof would be the grandfather, his son and bride, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. A new house and additional rooms would be built immediately next to the paternal home.

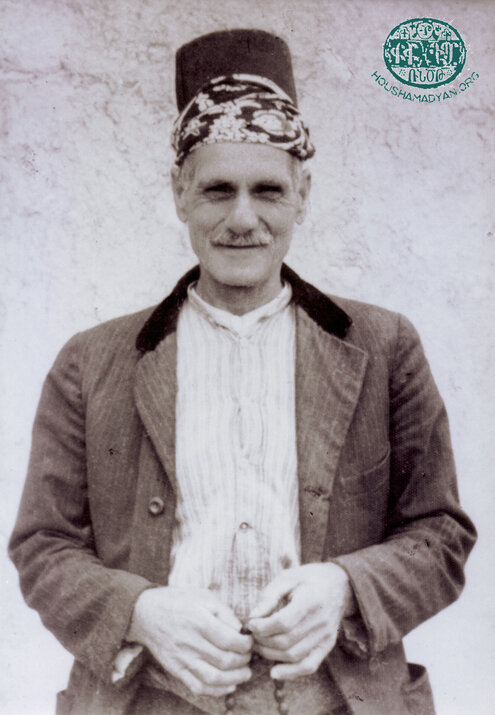

Armenian family from Mousa Ler; Identity unknown. Photo probably taken before 1915 (Source: Mousa Ler Compatriotic Union, Armenia)

Familial Relations

It is believed that the founding of Mousa Ler started from the village of Yoghoun Olouk. The other villages (Vakif, Kebousiye, Bitias, Kheder Beg, and Haji Habili) were established later as the settlement expanded. Residents of all six villages were related. The entire community participated as one at holidays, both happy and sad. “One could linger listening to the sound of the drums,” says the folk adage. The non-written law of assisting each other was another manifestation of a united community. During periods of extensive work (selecting and boiling wheat, cooking tomato paste, filtering oil or making soap from laurel leaves), neighbors, relatives and in-laws would voluntarily come to help out; to hasten the work and make it easier.

The unique application of vocatives in the dialect was another expression of the patriarchal lifestyle and close-knit relations. Thus, for example, the wife of one’s father’s brother was called aghpurgin; the spouses of one’s mother’s or father’s sister were called morkurar (mor+koyr+ayr) and horkurar (hor+koyr+ayr). One’s paternal grandmother was called dadimar, and the maternal, kirmar (kerou mayr). The mother of the godfather was called baboumar (bab=boub=gnkahayr). Of special note was the widespread use of pseudonyms; names that the community gave to all the elders, based on one trait of the person’s nature or a special incident, as a mark.

Prior to Engagement

Boys and girls younger than five were considered children. Afterwards, a girl became her mother’s helper and eventually a housewife. She would learn and perform all the housework – sewing, needlework, cooking meals, cleaning the house, washing the dishes and doing the laundry, etc. She would only leave the house with her parents’ permission. Talking, joking, playing with boys was not becoming, even if it was a relative. One must attend church and abide by all religious rituals. Girls from 15-20 were considered of marriage age. However, they had no say in the selection process. Parents chose a suitable groom and girls had to comply. Boys, though, were allowed to attend school, to play freely, to go to the village valleys, to climb the mountains, and to help their fathers with agricultural chores. Boys, especially after the age of 15, were somewhat wild and carefree, even though they were obliged to respect their parents and elders. Reaching 16, a boy would have to learn the use of firearms and to hunt. They were eligible for marriage after hitting 18, when they were able to provide for a family. A boy had the right to tell his parents about his choice for a bride. However, he could only engage in marriage negotiations with his parents and with their permission. [1]

Special women’s circle dances, performed on Paregentan and other holidays and pilgrimages, would attract loads of spectators. These events allowed boys to view the opposite sex from afar and pick out prospective brides. Generally, it was forbidden for members of the opposite sex to meet. The clever boys would still away at night to rendezvous near a girl’s home and profess their love vows. Oftentimes, such random meetings would occur on the way to church, where boys and girls would give each other facial signs professing their preferences.

Marriage with non-Armenians or relatives was strictly scorned upon. Each time a marriage candidate was chosen, the village priest or family elder would be asked to count “how many umbilical cords separated the couple”. Sometimes, even marriages between members of the different churches (Apostolic, Catholic and Protestant) were difficult. [2]

When a boy’s parents focused on a girl candidate, they would take an amount of salt and follow developments in the house during its use. If that trial period was successful, it meant the girl’s inclusion in the household would have positive results. They would start to take an interest in the girl’s behavior and health, and then prepare to ask for her hand.

Asking for her hand

The village priest was the most trustworthy person to perform the “asking for the hand” ritual. He would be joined by the most revered relative in the extended family. After the girl’s parents were informed, they would utter the words kherlayi iseh, nasib tgh uhnnou (If it is good, let it be lucky) and ask for time to consider the matter and to collect information about the boy and his family. If there were no objections, during the next meeting they would say words of encouragement but still not give a final answer. They didn’t want the in-laws to think that they sold their girl cheaply. [3] If their answer was no, the girl’s parents would delicately make their decision known by saying: “Our door is always opened to friends, however, we request that you do not raise this issue again.” If the girl’s parents again ask for time to consider the matter, it’s assumed the deal is done. It is only during the second in-law visit, after much requesting, that the elder of the girl’s side says: “Yehper alayrut meym ighodz uhk, cha eh buhr shinim, tuh khirla iuh, tuhgh uhnnou” (When all of you have come together, what can I do? If it is good, so be it). They would serve their guest sweets and syrup and jointly chose a date for the engagement. [4]

Nshantrek (Engagement)

The engagement ceremony was a low-key affair, with a proper modicum of hospitality and merrymaking, amongst close friends and relatives. People from the boy’s side would prepare the engagement ring, but it could also be an earring, bracelet, string of beads, coupled with a handkerchief or headscarf. They would take sweets and fruit in a daboukh (a trough-like vessel woven from wheat straw) and on trays. The boy’s side would include the priest, his parents, the godfather, and a few relatives. But the candidate could not be present at the engagement ceremony; a centuries-old crafted theatrical performance.

The priest would speak first, saying: “With an order from God, according to the patriarchal order and by the desire of the aghas present, we have come to ask for your girl, Azadig, for Hagop, the son of Sarkis of Ayntab. Kherluh niufius muh ireo (make a good verdict).”

The girl’s parents would make balk at agreeing, answering: “Der Hayr, all of you are welcome. But what you want is very expensive. The girl has a master.”

The boy’s side: “You are right. Give us some drink and appetizers…”

To honor the girl’s father, the godfather would address him first, saying: “Is eshgeyn chounim, eshgeyn ayrn eh.” (I have no girl. The girl is his.)

The in-laws would then serve the godfather who, after talking at great length and feigning difficulty, would finally express his agreement. However, he would then add: “Emmuh eshgeyn bebeg ou neneh gouna, ishink iruhnk cheh gou esin.” (But the girl has a grandpa and grandma, let’s see what they say).

The in-laws would serve them and joke: “Oh, that’s quite easy…ammo (the uncle, meaning the grandpa) is a good man. He won’t reject us.”

Finally, when all agree to handing over the girl, the Lord’s Prayer would be sung. Then one of the people in the boy’s party would shoot off a gun in the yard as a sign of success and news of the good tidings would thus spread. The priest would give the ring to the mother or godfather. They, in turn, would call for the girl and tell her that she has been engaged to this or that boy and would give her the ring. (Girls were not present at the ceremony as a sign of their modesty) The girl would then kiss the hand of all present, starting with the priest. [5]

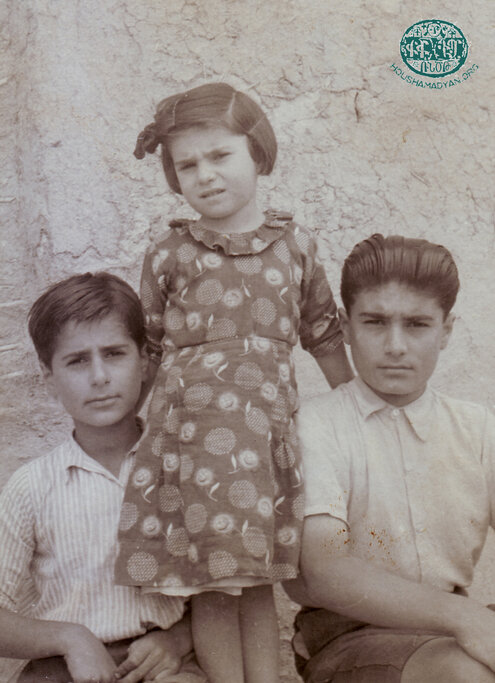

Armenian family from Mousa Ler; we believe this photo shows one branch of the Boursalian Family. Front row, left to right is Bedros Boursalian and his wife Kohar Boursalian (born Garabedian). Back row on the far right is their daughter Elmast Boursalian who married into the Shamassian family. (Source: Mousa Ler Compatriotic Union, Armenia)

The next day, a delegation of women relatives and friends from the boy’s side, headed by the mother-in-law, carrying presents and daboukhs would head off to visit the bride to be. The girl would have to stand during the entire time while serving the guests. When not serving, she would stand by the wall, hands placed on her chest, opposite the mother-in-law. In both houses fruit drinks would be served to well-wishers. When collecting the glasses, the girl would kiss the guests’ hands. The guests would wish her well:

- Shiud khntous, abrakinishendzon (May you be very happy. Long live the engaged)

- Asdoudz tgh khntatsnuhzki (May God make you happy)

- Asdoudz nishendzot tgh pakhshisheh (May God sustain the engaged)

- Affaruhm kuhzuhm, harsnaitsuht kuhtitsou dzeir puhr grim (Congratulations my girl, I will bring a large basket of water to your wedding)

As a blessing to unmarried girls they would say: “Asdoudz ki aghveyr nishendzo muh tgh oudou” (May God give you a good betrothed)

After getting engaged, when congratulating the boy, the custom was to pull the ears of the boy, with advice to take care. Afterwards, visits back and forth would be frequent and congenial. However, the boy never had the right to visit the girl’s home. Instead, he would be entertained with great love and respect by his relatives. Even though visitations were forbidden and the couple was obligated to avoid any chance meetings, there were always clever boys who secretly planned to meet their betrothed. [7]

After getting engaged, the girl was a guest in her father’s house. She became the focus of attention of all, both members of the household and especially her in-laws, who would come to visit her with sweets and presents to fawn over their bride to be. Sometimes, such visits would be so frequent that the girl’s entourage would joke: “Aruhk, januhm, aruhk, katsuhk tsir amaneout, khalisim.” (Take her, please, take your investment and go, free me.”

While engaged, the girl would assist her future husband’s family perform any big jobs – boiling grains and preparing bulghur, gathering olives and laurel leaves, preparing tomato paste or yoghurt. Another of her obligations was to clean and iron her future groom’s clothes once a week. [8]

The tradition was for every girl to prepare her dowry. Cloth and thread presented to the future bride as gifts during visitations would serve to make special needle work linens and lace. The act of donating money was called oujgil (ojdel – to endow/allot), and was meant to help the couple with their wedding preparations. During this time, the bride to be would sew lace adorned handkerchiefs and headscarves to give as wedding gifts to the adult men and women on the bridegroom’s side. [9]

1) Needle work kerchief made by bride to be presented as gift to women of the groom’s party.

2) Bead adorned kerchief. Belonged to Victoria Tashjian (nee Sarkahian). From Mousa Ler village of Yoghoun Olouk (1899-1941).

3) Multi-coloured lace belt. Belonged to Garabed Tashjian from Mousa Ler Yoghoun Olouk village (1894-1981)

(Source: Sonia Tashjian collection, Yerevan)

Weddings

Preparing for a wedding was a long process. First, the groom’s parents would go to town to do shopping – cloth to sew the bride’s wedding dress, her shoes and other gifts.

A few weeks before the wedding, on a Sunday, the mother-in-law (along with women friends and neighbors) would visit their in-laws to sew the wedding clothes. The girl, for her part, would invite her girlfriends and female relatives. A modest reception would be prepared. A women tailor, escorted by the mother-in-law, would measure the girl while the mother-in-law opened the ghoumashi bokhchen (cloth packet). While shaping the cloth, the tailor would express her congratulations: “Shinifir tgh uhnnou, Asdoudz tgh khuntatsni ztsiz, alinays ouchquh lays” (Congratulations, may God grant you happiness. Congratulations to all of us). Meanwhile, the women would start the zghluhtel (joyous exclamations in shrill and high notes). The young girls would sing happily. The mother-in-law would dribble wheat seeds on the head of the bride. Members of the household would serve sweets and fruit drinks to those present. [10]

On the Thursday preceding the wedding, the women would gather to clean the wheat for the harisa meal, to filter the bread flour, to bake the bread and the harsuh trakh (bride kata). The youngsters would start to slaughter the meat animals. The meat for the klour (gololag-kufteh) must first be cut thin, a portion pounded on a mortar. Afterwards, the women would start preparing the klour. Another group of women would start wrapping sarma. Others would make banuruhouts. On Friday they would go to bring dhol-zourna players. The sound of these instruments would announce the start of the wedding. A procession would bring the bride’s clothes and presents. Needlework handkerchiefs and doulakh’s (headscarves) would be sent from the girl’s house to the groom’s house to be distributed to his relatives. Then the girls, each taking one jar of wheat, would head off, singing and dancing, to the village spring for the ceremony of washing the harisa wheat. On the return, cauldrons would be placed on the fireplace and the harisa would start cooking. By this time, dusk had descended. The bride is at the house of the godfather. The godmother has bathed the bride and attired her. Festive tables are prepared in the yards of the godfather house, the bride’s, and the groom’s. Accompanied to the sounds of the dhol-zourna, the people would form a procession, brandishing oghi bottles and grilled meat skewers, to come and take the girl. The young men would place the oghi bottle to everyone’s lips so that all would drink and participate in the festivities. The groom would send a bottle of oghi, pastries and a fried chicken to the godfather’s house as a sign of gratitude and thanks. The girl’s parents, in a similar vein, would send a pair of shoes to the godfather and some expensive fabric to the godmother as gifts. [11]

Taking the bride from the godfather’s house, the procession would sing and dance towards the brides’ home where the henna ritual would take place. A jug full of henna is placed on a tray festooned with flowers. On the top is a red apple. An adult woman skilled at using henna enters the room and asks the mother: “Shall I henna your girl?” To which the mother answers, “Yes, henna her. You, expensive; what you desire, cheap. Just so long as my girl is lucky. Best of luck to all those who desire it.” [12]

The girl embraces her parents and is given permission to be painted with the henna. The henna is sprinkled with oghi and the bride’s palms are painted; sometimes also the feet. The bride’s girlfriends also follow her example to receive luck. At this time, one of the bride’s girlfriends cleverly steals the red apple, takes a bite, and passes it on to the others; as a sign of good luck. They lift a bit of the henna from the bride’s palms to use as a starter (magatrich hius) to use of the groom.

The bride’s party and in-laws return together to the groom’s home. The bride remains behind with her family where the feasting continues. In the courtyard of the groom’s house festivities on a greater scale take place – tables laden with food and drink, and circle dances, fueled by the dhol-zourna music, continue until the wee hours of the morning. The musicians are often paid by affixing paper money to the foreheads as they play. To paint the groom with henna, people give presents to the girl’s godfather to receive permission. They then start looking for the groom who has been “kidnapped” in order to free him. They demand a ransom. The boy’s relatives give money, pieces of meat and oghi to the playful lads so that they bring the groom and start the henna ritual. Before kneading the henna, the painter asks those present to certify that henna is in the vessel. The painter then asks for the henna ‘starter’ taken from the bride’s palm to mix with the new henna. One of the bride’s girlfriends has been holding on to the ‘starter’, and she must be given a gift to hand it over. They knead the henna while singing the following special song:

- Isgoum tesen meyjuh hina guh shaghin

- Arzout sendrou mezzeonkuh guh sandrin,

- Kuh aghprdakuh srou guh bahin.

- Kalashuhs, aman, Aghviuruhs, aman,

- Uhnnim ta virenkuh ziurss iursoum,

- Ijnim ta tsadzankuh srou ginoum,

- Geomkuh inim aghjiloum, baghdiloum.

- Kalashuhs, aman, Aghviuruhs, aman.

- Translation:

- They knead henna in a golden bowl.

- They comb hair with a silver comb,

- You brothers wait their turn.

- My dear, aman, my lovely, aman.

- Let me rise up to hunt my prey,

- Let me descend down, to wait my turn,

- Let me do my will by pleading-beseeching.

- My dear, aman, my lovely, aman.

The groom embraces the household members as a way of saying thanks and receives the right to get the henna treatment. To paint the godfather with henna, the kidnapping and ransom rituals are repeated in order that a large number of presents are collected for use in upcoming young people festivities. There is a tender tradition where boys in love take a small ball of the henna and secretly send it to their sweethearts as a sign of their love…

On Saturday, the first ritual (halavorhnek) is to dress the groom and his best man (khachyeghpayr). In the presence of the priest and deacon, the garments are blessed. Then, specially selected young men assist them to dress. At the very end, they tie red and green handkerchiefs to their chests. In the meantime, the priest is praying, the women ‘shrilling’ (zghluhtel), and the adolescents are shooting in the air.

The village mayor (kzir) brings a horse festooned with a rug. The procession starts off towards the house of the bride. Adolescents, brandishing rifles, are at the head of the procession holding the reins of the horse and carrying a flag. At the bride’s house, the godmother blesses the veil brought by the in-laws by turning it three times around the bride’s head. She chants: Light of lights, a belief in God, Say congratulations.” The brother approaches to put the shoes on his sister’s feet (after placing some paper money in them) and to tie the belt around her waist. Of course he too must be given a gift. The bride takes her leave of the house to a chorus of goodbyes and congratulatory songs:

- Hey yama, hikkes yama.

- Kisheruh knit mnatsir, tsiriyuh` penit,

- Ki nazluh ashguhnen khatruh irir.

- As uhntsi layuhk chir, em aghporuh layuhk ir.

- Peruh mnous, shin ginous…

- Hey yada, yada, ey januhm yada.

- Sheet charcharvitsour, eshgein mindzutsir,

- Taoun chgirour, zeys girtsutsir,

- Taoun zuhgvitsour, zeys haktsutsir,

- Peruh mnous, sin ginous…

Translation:

- O Mother, mother, mother of my soul,

- You remained awake at night and failed you work during the day,

- You performed the will of your sweet girl.

- This didn’t suit for me, it was proper for my brother.

- Good bye, be well…

- O father, father, o wonderful father,

- You were greatly tormented, you raised a girl,

- You didn’t eat, but fed me,

- You sacrificed, you clothed me,

- Good bye, be well…

If there was a brother or close relative living as an emigrant in foreign lands, the bride would remember them too with a song.

- Hey aghpar, aghpar, hikes aghpar.

- Poundzuhr lironkuh tgh tsetsnoun,

- Tsouts ambiruh tgh pandzrnoun,

- Hiraou jampounkuh tgh grjgnou,

- Trtsiun dziuk muh tgh uhnnous,

- Hesnes kuh sirouts kairuh,

- Jampounk tgh tnes,

- As uhntsi layuhk chir, ki layuhk ir,

- Peruh mnous, shin ginous…

Translation:

- O brother, brother, brother o my soul,

- May the mountains tremble,

- The low clouds rise,

- The distant roads grow shorter,

- May you be a flying bird,

- May you reach you beloved sister

- Send her off.

- This didn’t suit me, it suited you.

- Goodbye, be well…

As a rule, the bride and her girlfriends, and women relatives, would cry profusely when the bride left. After placing the bride atop the horse, the groom would approach the girl’s parents to express his thanks. The mother-in-law would present him a copper bowl and two spoons as a gift. When the groom shook the hand of his mother-in-law she would bless him by saying, “May you enjoy the gifts of your wife.” [13]

The most popular wedding song is “Hele, hele, ninnoi eh”. It has many verses:

- Garmehr fsdan hakouts i

- Heleh, heleh, heleh, ninnoi eh.

- Chouts al aghvir villoudz i,

- Heleh, heleh, heleh, ninnoi eh...

- Gighitsen poyuh katsouts i

- Buhr nshanvem asouts i:

- Tanjaran gou kuhbuhrtou

- Duhvuhk zeshhein tgh ourtou:

- Zeshgein ouzoughen duhvuhk

- Sadka ourtou tgh khntou.

- Eshguhnen enaoun Ighisa

- Is zki tabakin diso.

- Varuhm-yoghuhm tsekhitsa

- Uhnnoum ko deden pisa.

- Tiniruh gipin zhoutsuh,

- Tuhpirin guhnni oudzuh.

- Ebeoruh gipa igh chgou

- Khnemekuh goukoun, digh chkou.

- Shoud ouzitsa` chduhvein

- Duhvein zuh ishuh kourgen.

- Tsitir i lousn laisuh

- Sirim zichoutsuhn laisuh.

- Ninna, yavruhm, ninna eh

- Tsirven-vuhdven hina eh.

Translation:

- She was wearing a red dress,

- Heleh, heleh, heleh, ninnoi eh

- It really suited her

- Heleh, heleh, heleh, ninnoi eh

- She’d gone to the church yard

- I’m getting engaged, she said.

- The cauldron boils,

- Give the girl, let her go.

- Give her to the one who wants her

- May she laugh till she dies.

- The girl’s name is Yeghisa

- I saw you from the window.

- I sold whatever I had

- Let me be your father’s groom.

- The snake comes out of the bushes.

- The soup cooks` there’s no fat.

- The in-laws are coming` there’s no room.

- I really wanted it, they didn’t give.

- They gave it to the foal of his donkey.

- The moonlight breaks,

- I love the light of eyes.

- Ninna, my soul, is ninna, (dance)

- Your hands-feet are henna. [14]

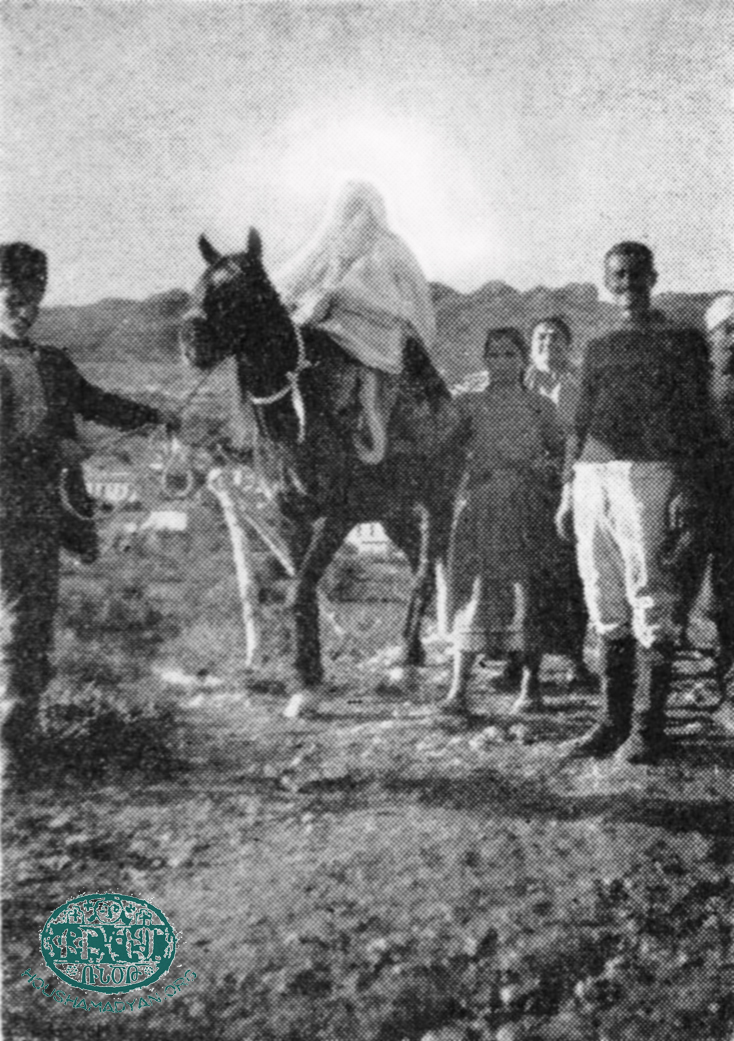

The Makzanian family from the village Bitias in Mousa Ler, ca 1892. Back row, standing (the two children), left to right: Hovagim Makzanian, Stepan/Peter Makzanian. Middle row, left to right: Hagop Makzanian (father), Anna Makzanian (mother, nee Sherbetjian), Samuel Makzanian (standing). Front row, left to right (seated): Hovhannes Makzanian, Movses Makzanian (Source: Richard and Louisa Furno collection, USA)

The crowd, performing a circle dance, heads for the church. Along the way, women standing outside their doors throw grains of cereal on the bride. They utter blessings and the high-pitched exclamations of joy (zghluhtel). When they near the church, the music stops. They enter in reverential silence.

After the marriage ceremony, the bride is again seated on the horse and taken to the groom’s home. At the door, the groom’s father scatters coins on the bride and his wife, a mixture of sugar and grain. They then promise gifts (zengilik-stirrup rent) to the bride. It can be a calf, a fruit tree, a piece of land, etc., according to their ability. After dismounting the horse, the mother-in-law places loaves of flat bread on the shoulders of the newlyweds as a sign of prosperity. She gives the bride a pitcher to smash on the floor, in order to ward off evils spirits. She then gives the bride a ball of dough to affix to the entryway, to keep the house strong and full of love. The bride is then given a pomegranate to break open, so that she bears children as numerous and beautiful as the seeds. Fragrant leaves and incense is then used to perfume the bride, who is taken to the bridal chamber.

The wedding festivities continue on Sunday. Dancing, they carry the bride’s dowry - bedding items, pots and pans, a mirror, a water pitcher, a clothes trunk, etc. The groom greets them and hands out gifts as he takes the dowry.

On Monday, the godfather organizes a family dinner celebration called the pesaverkhnjouik. Then, they take the groom out for a walk (pesayabdouid). Afterwards, in the evening, the priest comes to remove the narod (traditional woven headdress) from the heads of the newlyweds and to allow the groom to enter the wedding chamber. This is accompanied by the groom’s friends firing their rifles in the air. The next day, an old woman goes to the home of the bride’s parents with the good news; taking the red apple with her. [16]

The bride wears a veil for quite some time in the house. She doesn’t speak to her father-in-law until she bears her first child. She can only visit her parents when accompanied by her husband. The bride is subject more to the wishes and demands of her mother-in-law than those of her husband, because she’s the one who supervises all the in-house chores. [17]

While eloping was frowned upon, there were cases when a young couple went against the wishes of their parents and eloped to get married. Naturally, after a period of arguments and threats, they reconciled with their folks. There were also occasions of the “visiting a son-in-law”. This happens when a father-in-law (wife’s father) has no boy child and the groom comes to the house to assume all home-related responsibilities.

Births

Other than being treated with care, special attention was not paid to pregnant women. Samples of a new batch of fruit or vegetable, or a taste of a scrumptious meal, were first given to pregnant women so that it couldn’t be said later on that the woman wasn’t given her share. Pregnant women weren’t allowed to see unpleasant scenes out of the fear that they would have a negative effect on the baby within.

In the last months of the pregnancy, one of the men in the house would order a cradle to be built and the grandmother would prepare the mattress, blanket and pillow.

Childbirth would take place next to the fireplace in the home. The nurse and a few experienced elderly women neighbors would assist in the delivery. The nurse would cut the umbilical cord and tie it off. The baby would be rubbed with salt powder, especially the folds of the body. The baby would be wrapped in diapers. After receiving a gift of money or clothes, the placenta would be taken and buried in some secret place.

The nurse would arrive the next day to remove the salt and wash the infant. It was imperative to place some sort of metal object in the basin to ward off evil spirits. A knife or scissors would have been placed under the infant’s pillow the day before. A blue bead would be hung from the infant’s hat. The bath water would be poured in the cracks of the walls. The mother would feed the infant sweet porridge and, after a few days, sweet red wine. [18]

The birth of a child was a joyous occasion for the family, especially if it was a boy. The boy would be given his grandfather’s name. A girl would be named after the grandmother.

In the villages of Mousa Ler, as elsewhere, the mother and infant would be separated from the rest of the family for the first forty days. Visits were kept at a strict minimum. To celebrate the good tidings, presents (karsanak) were distributed to the relatives and friends received sweets. [19]

The 40 day old infant would be taken to the church where the priest would say a special prayer of protection. This ritual was called karasounken hanel.

To care for the infant, a white lime was brought from the mountains. It was first dried in the sun or wind and then preserved to be used when needed. To change the baby’s diaper, the mother would spread a piece of cloth on a special mattress placed on the ground. She would cover it with clean lime and add another cloth on top. The infant would be laid atop this. This would be folded around the baby’s legs and another cloth would be securely wrapped around both the legs and hands so that the entire thing wouldn’t unravel. The lime would absorb any dampness when the baby wetted itself. [20]

Baptism

Babies were baptized when they were a few months old; preferably during the first month. On the day, the child’s father would visit a nearby town to purchase an appropriate gift for the godfather (usually a pair of shoes). All church related expenses were paid by the godfather. After the service, it was traditional for the godfather to carry the child back home and to offer a gift of a few yards of expensive fabric. The priest would then take the child from the godfather’s embrace and hand the infant to the mother. [21]

Three days later, the godmother would come to bathe the baptized infant. A metal item would be placed in the basin, as a gift, and the water would be poured over the roots of a tree.

A late talking child would be taken to the church. The priest would take the key to the main church door and move it around the inside of the infant’s mouth in the belief that the ritual would “open” the infant’s tongue. [22]

Teething

The appearance of baby teeth would cause the infant teething pains and crying. The child would be given a green onion to munch on as a way to neutralize the discomfort. When the first tooth appears, the grandmother would boil some wheat grains (or other cereals) and invite relatives to the agrahadig ceremony. The infant is seated on a table, a veil covering his/her face. Grains are dropped on the baby’s head and then they wait for the infant to pick up one of the items placed in front; thus predicting his/her future livelihood/profession.

Death and Burial

When a person dies the church bells would ring out the sad news in a monotone chime and all the villagers would attend the funeral. After the burial, the deceased’s relatives would prepare meals for three days and send the food to the church for the clergy; who also ftern distributed a portion to the poor.

The custom was to call for a priest when a person was at death’s door in order to give the last rites. After a person died, the pillow would be removed from under the head and the room’s windows would always be opened. The body would be bathed, wrapped and a coffin immediately ordered. The deceased would be taken to the church for the funeral rites and only after to the cemetery. On the way home, women neighbors and relatives would offer words of console and solace, and help out with the house work and meal preparation. [24]

- [1] Hapet M. Iskenderian, Customs of Svediye [in Armenian], Cairo, 1917, p. 11.

- [2] Krikor Kiozalian, Ethnography of Mousa Ler [in Armenian], Yerevan, 2001, pp. 148-150.

- [3] Mardiros Koushakdjian and Boghos Madourian, Memory Book of Mousa Ler [in Armenian], Beirut, 1970, p. 163.

- [4] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 151.

- [5] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 164.

- [6] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 152.

- [7] Customs of Svediye, p. 12.

- [8] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 145.

- [9] Tovmas Habeshian, Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh [in Armenian], Beirut, 1986, p.14.

- [10] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 153.

- [11] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 166.

- [12] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 155.

- [13] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 168.

- [14] Verzhine Svazlian, Mousa Ler [in Armenian], Yerevan, 1984, pp. 118-123.

- [15] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 23.

- [16] Customs of Svediye, p. 16.

- [17] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 170.

- [18] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 169.

- [19] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 27.

- [20] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 170.

- [21] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 170.

- [22] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 174.

- [23] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 170.

- [24] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 182.