Palu - Popular Medicine

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 14 January 2012 (Last modified 14 January 2012) - Translator: Shogher Margossian

Located far from trade routes and with its isolation from surroundings due to its geographic position, Palu has long lived a social and economic stagnation. This rural area has generally remained distant from the developments and modernization atmosphere of the surrounding cities such as Kharpert/Harput and Diyarbekir. One indicative of this phenomenon is the health service system in Palu. Until the fall of the Ottoman Empire, only one doctor's presence is mentioned in the whole of the province. Shefik bey was a Turkish doctor, who had settled in the city of Palu only a few years before the outbreak of World War I. The only pharmacist was Karekin Kuredjian of Palu who was a graduate of the American University of Beirut and who had also settled in Palu during these years. For surgical procedures, patients had to go all the way to Kharpert/Harput or Ayntab. [1]

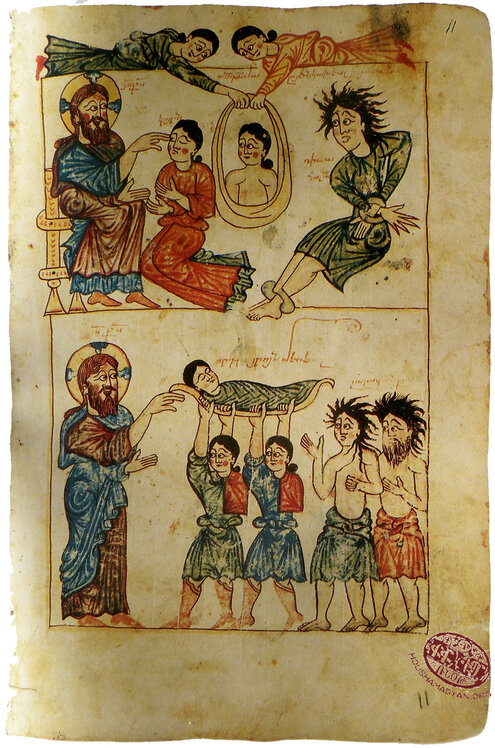

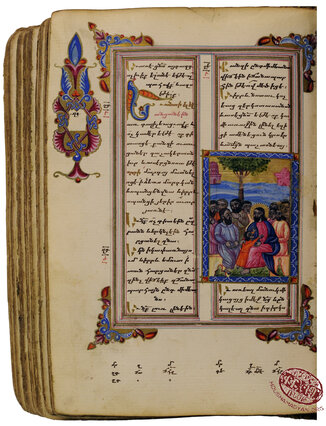

1) ‘The sick ward’ a miniature painting by Hovhannes of Vasburagan (Source: Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts - Matenadaran, Yerevan, in Tamara Mazaéva, Hratchia Tamrazyan (editors), La miniature arménienne, Ed. Naïri, Erevan, 2006)

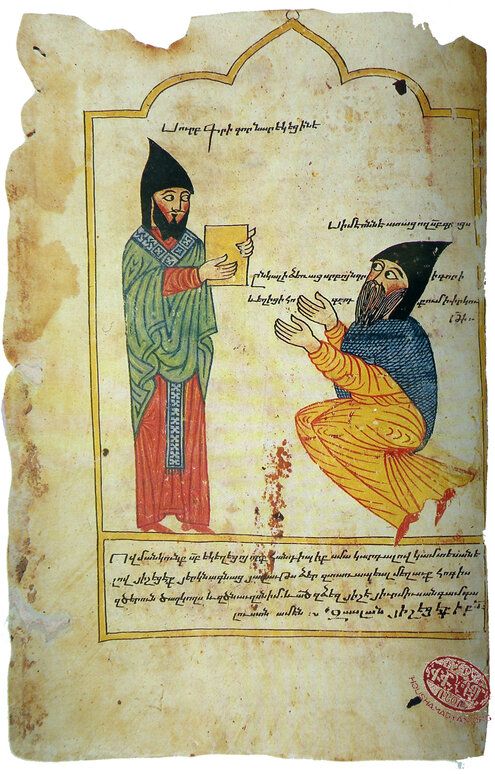

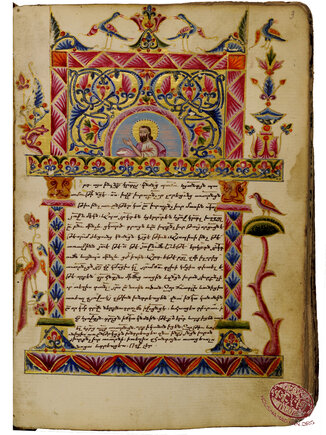

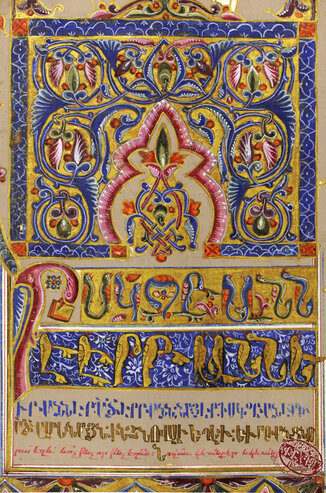

2) Gregory of Nareg and Simeon the monk. Miniature painting by Dzerun Dzaghgogh of Vasburagan (Source: Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts - Matenadaran, Yerevan, in Tamara Mazaéva, Hratchia Tamrazyan (editors), La miniature arménienne, Ed. Naïri, Erevan, 2006)

As such, and in such conditions, popular medicine has always had an important role in the health life of the Armenians of Palu. When people are unfamiliar with medical innovations and when contemporary medicine is not accessible, the old and the traditional are firmly kept and native people continue to believe in popular medicine. Such an unlicensed doctor was, for example, Barbar Toros, a hairdresser from the village of Sakrat, who had a big volume of manuscripts of medical treatments at his disposal; he followed the instructions in the manuscript and recommended medicine for various simple illnesses. At the same time, he was the best self-taught dentist of the whole Palu district, he extracted teeth, he punctured swollen gums or other swellings, cleaned the pus and treated them. [2]

There was also Krikor bey, the Persian vice-consul in the city of Kharpert/Harput, who had a good reputation as a folk healer. He also had a large volume at his disposal. The people of Palu often consulted Krikor bey to treat their illnesses.

It is also interesting to know that in Palu, patients were fed watermelons more than any other food. They never gave milk but rather gave pears, apples, cracked wheat (bulgur) soup and yoghurt drinks to the patients. [3]

Here we present different kinds of diseases, their symptoms and the local methods of treatment. This information is taken from reverend Harutiun Sarkisian’s book on Palu.

Shiver (togh)

The most spread disease in Palu, somewhat the calamity of the province. It generally appears at the end of summer and disappears in the beginning of winter. Starting with shivering and frostbite, this illness immediately turns to rise in temperature. Every year, the majority of the population of some village is infected by shivering. It is more present in field villages where dampness is stronger.

There are various methods of treatment for this illness in Palu. Firstly, the patient is bathed with cold water and then laid in bed. Sometimes they make the patient drink quinine, which is more of a malaria medicine. There is also a locally produced widespread medicine in Palu, which is the grass called catnip (mayram). This grass is boiled well and the remaining liquid is used as medicine. In some villages, they use the shiver-thread (toghgab) as a means to fight against this illness. The toghgab is a thread blessed by the priest which is tied to the patient's wrist. The same priest or praying person makes 7 knots on the wrist thread. As such, it is believed that the shivering is “tied”, or in other words it is vanished. The 7 knots also symbolize shivering which lasts 7 years, which according to the villagers, is the worst type of this illness. [4]

Thin-pain (parag tsav)

It is assumed that this disease corresponds with the tuberculosis. It is rare. It is called “thin” as those who are infected do not suffer from severe pains, but simultaneously have long-lasting fever, are worn out, lose their appetite, look pale, and lose weight. Given the conditions in Palu, their death was generally inevitable. [5] There were no doctors in these areas, thus people were powerless against this disease. They visited sanctuaries instead, took vows, read Nareg and the Bible and relied on God's providence.

Dard or Frangakhd (syphilis)

People are very cautious of those infected by this disease, given that dard is considered a very contagious illness. Once wounds appear on a person’s various body parts, and at the same time his/her voice turns hoarse, then people, rightly or not, consider him/her dard-y or infected by dard. They stop dining with him/her, and stop taking things from his/her plate and do not use his/her cutlery. For this disease, people never resort to prayers and vows. They immediately try to find a doctor, licensed or traditional, and follow the doctor’s instructions undeviatingly.

Hakim Kevo [6] had the reputation of a healer of this disease who was from the Pazmashen (Bismişen/Sarıçubuk) village of Kharpert/Harput. He went to Palu once a year and treated those infected with this disease. He received wheat and money for his services. Hakim Kevo’s cure was mercury which he mixed with other materials and turned into pills. He advised a strict diet to the patients, who especially had to stop eating sour, spicy, and salty food, and advised them to stop drinking cold water. Sometimes instead of having the patient swallow the mercury pills, he heated the mercury on fire and made the patients inhale. Compared to thin-pain (parag tsav), dard is a more widespread illness in Palu. According to Sarkisian, those infected by dard are those who went to Istanbul as immigrants, who caught the disease there, and later returned to their native home. The same author states that this illness has never been observed in Palu’s women. [7]

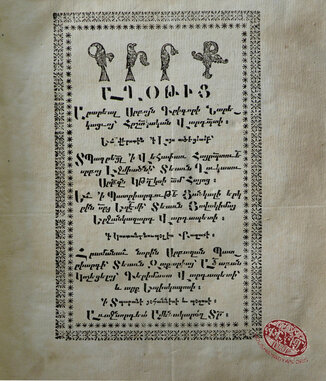

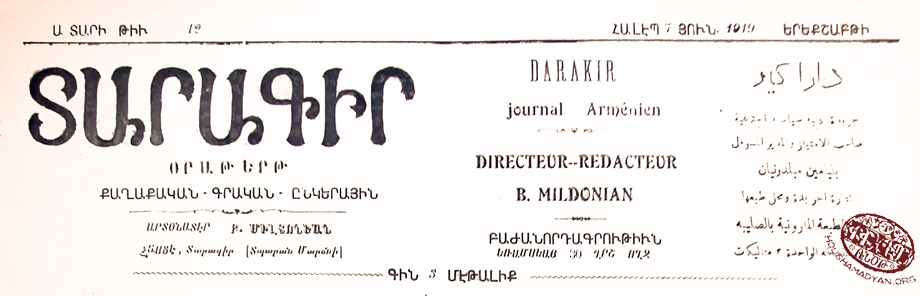

Aleppo, 7 June 1919. Dr Hovhannes Hrechdakian’s (originally from Urfa) notice printed in the daily newspaper ‘Darakir’. It says: ‘He cures sexual diseases, hydruresis and syphilis using the latest methods. He receives patients from 9 until 12 in the morning and 2:30 until 5:30 in the afternoon. Free treatment for the poor on Fridays. Opposite the former Istikhbarat Salon.’

Eye pain

This one is more common during the summer - during field work or during harvest. The symptoms are reddening of the eyes and vision blackouts. Various medicines are used against this pain in Palu. The root of the plant called dandelion is squeezed and the milk-like liquid that comes out is dripped into the sickly eye, or the egg’s yolk and potassium sulfate are well mixed and the composition is put on a piece of cloth; before going to bed, this cloth is put on the sickly eye and is kept in this state till morning. [8]

Jaundice

The symptoms of jaundice for Palu villagers are the yellowness of the eye’s cristallin and the paling of the face. Various treatments are used for this disease; the following is the main treatment: a few pieces of dry apricots are put in a dish, human urine is poured over them, and it is put in the open air in the evening until morning. These apricots are fed to the patient during breakfast and this procedure is repeated a few more days. [9]

Har

This is the common cold for which the villager takes no medication. [10]

Darug or Darvenag

This is a wound which is considered typical to the Palu, Kharpert/Harput, and Diyarbekir regions. This wound can last a whole year. In Palu, as a treatment for this, they use the powder of copper sulfate, which is mixed with dough and put on the wound. Coffee powder is another treatment which is spread over the wound. [11]

Gab (knot/tie)

This is sexual impotence, which is considered a disease in this area. There are people in Palu who have the reputation of being people who “untie knots”; they pray on the person in question, tie knots on a (khazel) rope made of goat hair and hand it to the patient. [12]

Tsrtserug

These are wounds full of pus on the face; they use lead (sülüğen) for this, which is a red and poisonous metallic powder; this is especially used on ironware to protect against dampness and corrosion. For those who suffer from tsrtserug, lead is mixed with butter fat and this composition is put on the wound. [13]

Vartsav (typhus)

This is a long-lasting illness, which can last up to a month. The patient continuously has temperature, is in an unconscious state and raves. During this whole time, the patient feeds on yoghurt, cracked wheat (bulgur) soup, and drinks yoghurt drinks (tan) and water. There are no special treatments for typhus in Palu except praying for the patient, reading Nareg and the Bible, and making offerings to saints and visiting sanctuaries and holy places. This is a rare disease; death due to typhus is also rare. But it becomes the equivalent of a catastrophe when it acquires an epidemic nature. This is the case in 1896, when as a result of anti-Armenian massacres and destructions, thousands of Palu residents were left homeless and without refuge. It is known that during this era about 300 Armenians were suffering from typhus in the Palu region. [14]

Koush boghan (probably diphtheria)

The symptoms are inflammation of the throat, rise in temperature and difficulty to swallow spit. To treat this, they dry the dog’s excrement and turn it into powder. The condition is that this waste must be white. Then this is poured into a half-centimeter diameter tube (masura) and blown into the patient's throat. If, because of the dog’s waste, a swelling is observed in the patient's throat, then honey is spread over a tobacco leaf and tied around the neck. [15]

Dsaghig (variola)

This is better known as variola/small pox. The symptoms are rise in temperature, redness of eyes, cough, and the formation of blisters or pimples (shid in arm. [16]) on the body. As a treatment for small pox in Palu, the patient was kept warm and fed sweets, and drank syrup (roub). The explanation for this is that sweets have the property of driving the illness out of the body – on the skin. Palu people are convinced that in the case of small pox, if the patient's skin does not get pimples, then the illness can become dangerous. [17]

In Palu there is also vaccination, or parpin as is called in this region, against smallpox. This procedure is entrusted to elderly and experienced women; they take pus from a wound infected by smallpox with the tip of a needle. Then they approach the vaccination candidate, and draw the tip of the needle close to the part which connects the thumb to the forefinger and begin striking lightly, until this part of the skin starts to bleed. As such, the patient’s pus and the blood of the one being vaccinated blend on top of the open wound. Then the elderly woman cuts a raisin, takes out the kernel, ties it to the open wound, or on top of the parpin until the wound heals. As such, the vaccination is complete. [18] Those infected with smallpox don't bathe, and people are very cautious not to have water touch the patient continually for forty days. [19]

Erysipelas (khumrig)

In Palu, these are considered the symptoms of erysipelas: the patient's head and face get swollen, the skin gets darker, and the temperature rises. This illness can last 15 to 20 days. Sarkisian mentions that after healing, the patient’s whole hair could fall out. The same author adds that the hair would later grow back [20] with the same density.

Measles (harsanet)

In Palu, high temperature and red blots appearing on the skin are considered the symptoms of this disease. They keep the patient in a warm state and feed him sweets. [21]

Khagh eynil (to play, to make play)

In Palu this name is given to those who have nervous breakdowns (spasms), or more likely to those who suffer from epilepsy. As such, the person in question, falls on the floor, has shakes, and there is foaming at the mouth. All this may last one minute after which the person regains his/her self. In Palu it was believed that during this short period, the alk’s (evil female ghosts) attack the subject and play him/her. It is also said that the alk’s live alongside springs which means that such “attacks” are more likely to happen in the vicinity of running waters. For this reason, people who have gone through such distress are careful not to pass by waters. The Palu people don’t have specific treatments for such alk “attacks”. They are restricted to injecting cold water on the forehead and reading Nareg during the patient’s attacks. [22]

- [1] Mesrob Grayian, Palu: Pictures, recollections, poetry and prose taken from the life of Palu, Published by the Catholicossate of Cilicia, 1965, Antilias, p. 158. (In Armenian)

- [2] Rev Harutiun Sarkisian (Alevor), Palu: its customs, educational and intellectual state and dialect, Sahag-Mesrob Press, Cairo, p. 255. (In Armenian)

- [3] Ibid., page 261.

- [4] Ibid., page 254.

- [5] Ibid.

- [6] Ibid., page 255.

- [7] Ibid., page 256.

- [8] Ibid., page 257.

- [9] Ibid.

- [10] Ibid.

- [11] Ibid.

- [12] Ibid., page 258.

- [13] Ibid.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Ibid., page 259.

- [16] These are very small swellings appearing on the body, which ripen and hold pus (Armenian Language Dialect Dictionary, vol. 4, Yerevan, 2007, page 242).

- [17] Sarkisian, op. cit., page 258։

- [18] Ibid., page 259.

- [19] Ibid., page 259-260.

- [20] Ibid., page 260.

- [21] Ibid.

- [22] Ibid.