Palu - Population movements

There are no references in books written about Palu concerning the mass movement of Armenians in the past. In the case of other Armenian-populated cities, towns or regions, when the local population is made up of immigrants, settled in their new home as a result of deportations or wars, the custom is that there are always traces of that movement in the given region’s Armenian oral history. More than this, memorial books written about the given region generally point out the local Armenian population’s origin - which city or area they have emigrated from. References like this in the case of Palu are rare therefore we can suppose that the local Armenians have been residing there from ancient times. The exception in this sense is Parunag Topalian’s book, in which the author states that his family emigrated from Mush centuries ago and settled in Palu’s Okhu village.[1] Other memorial books about the same region note the immigration to Palu from nearby areas – as for example from Charsandjak – and their settlement in already Armenian-populated villages.

Town and villages

There are oral testimonies about the town which describe its past richness and size. Thus all those of the 19th century recall that the town of Palu is located on the right bank of the Aradzani River. Despite this, the oral history of the inhabited area points out that in more ancient times the town also spread along the eastern bank as far as the place called the Sheikh’s Kor, which is a cemetery.[2] It remains unclear as to when this decline in the town’s progress has taken place and what the reasons for the change are.

What is clear, however, is the fact that the decline of the town has continued throughout the whole of the 19th century and that details of it are, comparatively speaking, plentiful. Thus we know that the town has four Armenian quarters – Yerevan, Doner, St Sahag and St Giragos, the latter two named for their churches. But in the last decades of the 19th century only two of them have continued to survive – Yerevan and Doner. St Giragos is in a completely ruined and deserted state. St Sahag is almost the same, mostly in ruins while the quarter’s church itself is half ruined and deserted. During this same period it is possible to see demolished houses in other parts of Palu. One thing is certain: from this time on Armenian life is centred in the Yerevan and Doner quarters.

The reason for this decline is the general economic crisis that is destroying much in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire – generally in the Armenian and Kurdish populated towns and villages. The 19th century Ottoman-Russian wars, apart from causing huge human losses, at the same time are the reason for whole areas becoming bankrupt and suffering famine. Palu is a district like so many other eastern provinces in the Ottoman Empire, the central authorities being exceptionally slack and not succeeded in imposing their political and organisational will there. The absence of these authorities means that they are replaced by those of the local beys and aghas who use force to secure their positions. They have become the actual rulers and often have act as serf owners in Palu’s village circles, using local Kurdish and Armenian peasants for their own purposes. Finally, at the end of the 19th century – in 1895, the anti-Armenian massacres haven’t left out the district of Palu. During this mass violence many Armenian houses have been set on fire and demolished in the town and in the villages.

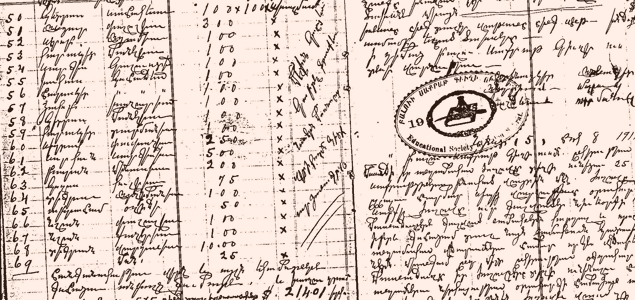

All these factors give great impetus to the Palu Armenians migration, the peak being reached during the 19th century. Men leave Palu and its villages and go to other Ottoman towns and cities to find work and earn money with the eventual aim of returning. The reality is, however, that very few of them return to their homes which over a long period of time gradually become deserted. The Palu people’s preferred places of emigration were nearby, like Kharpert (Harput), Kghi or Dikranagerd (Diyarbekir). The flight to even more distant towns and cities like Istanbul, Ayntab, Urfa, Aleppo and Adana has speeded up, and Armenians from Palu have gone to the latter city in Cilicia in large numbers, where there is a boom in the cotton industry. The peasant from Palu, who is already a skilled cotton cultivator, therefore becomes a sought-after human resource. The majority of the population of the quarter of the city of Adana known as Djamus Göl is made up of Armenians from Palu.[3] Later, from the first years of the 20th century, this current of emigration by Armenians from Palu has even reached as far as the United States, where they have begun to form reconstruction and educational unions. The aim of all this is to demonstrate mutual patriotic strength towards their home village or town, taking responsibility for building a school, providing scholarships or sending funds for the aid of the church. The first cities the refugees from Palu have chosen are Providence, Chelsea, Haverhill and New York.[4] It should be noted that this migratory current is evident among the Kurdish villagers of the district of Palu who, in their turn, have begun to migrate, taking the same routes.

An important number of the migrating Armenians from Palu have settled in Istanbul. For many of these exiles the only way to earn money is by becoming porters. But there is also an important group that in the Ottoman capital have, from the early days, started to ply their trades as carpenters and stonemasons: two trades that many of the people of Palu are very familiar with in their home town. Later a significant number of these exiles have become well-known builders (khalfa) in Istanbul. Thus over a period of time, some of these people from Palu, or their descendants, have blended into Istanbul life, changed their social status and have become notable people within the Armenian community or in Ottoman society generally. Istanbul architects and intellectuals belong to this group. For example Krikor Odian’s (1834-1887) father, Yervant Odian’s (1869-1926) grandfather Yazedje Boghos Agha is from Palu. In the beginning he establishes himself in Gesaria (Kayseri) then Istanbul. The parents of both Srpouhi Kalfayian (1822-1889), the founder of the order of Armenian nuns, and Yervant Aghaton (1860-1935) were people from Palu who had settled in Istanbul. The father one of Istanbul’s noted Armenian literary figures Levon Pashalian (1863-1943), was also born in Palu. The life of the exiles established in Istanbul is best described in Armenian literature by Melkon Giurdjian – with the nom-de-plume of Hrant – (1859-1915). He was born in the Armenian village of Havav and has moved to the Ottoman capital in his youth, staying and writing there. Hrant’s series ‘Emigrants Letters’ has begun to appear in the Istanbul newspaper ‘Massis’ towards the end of the 1880s, and is a collection of moving descriptions of the difficult lives lived by the provincial exiles living there.

[1] Parunag Topalian, My native village of Okhu (in Armenian), published by Hairenik Press, Boston, MA, 1943, p. 55.

[2] Mesrob Grayian, Palu: Pictures, recollections, poetry and prose taken from the life of Palu (in Armenian), Published by the Catholicossate of Cilicia, 1965, Antilias, p. 35-36.