Sassoun – Churches and Monasteries

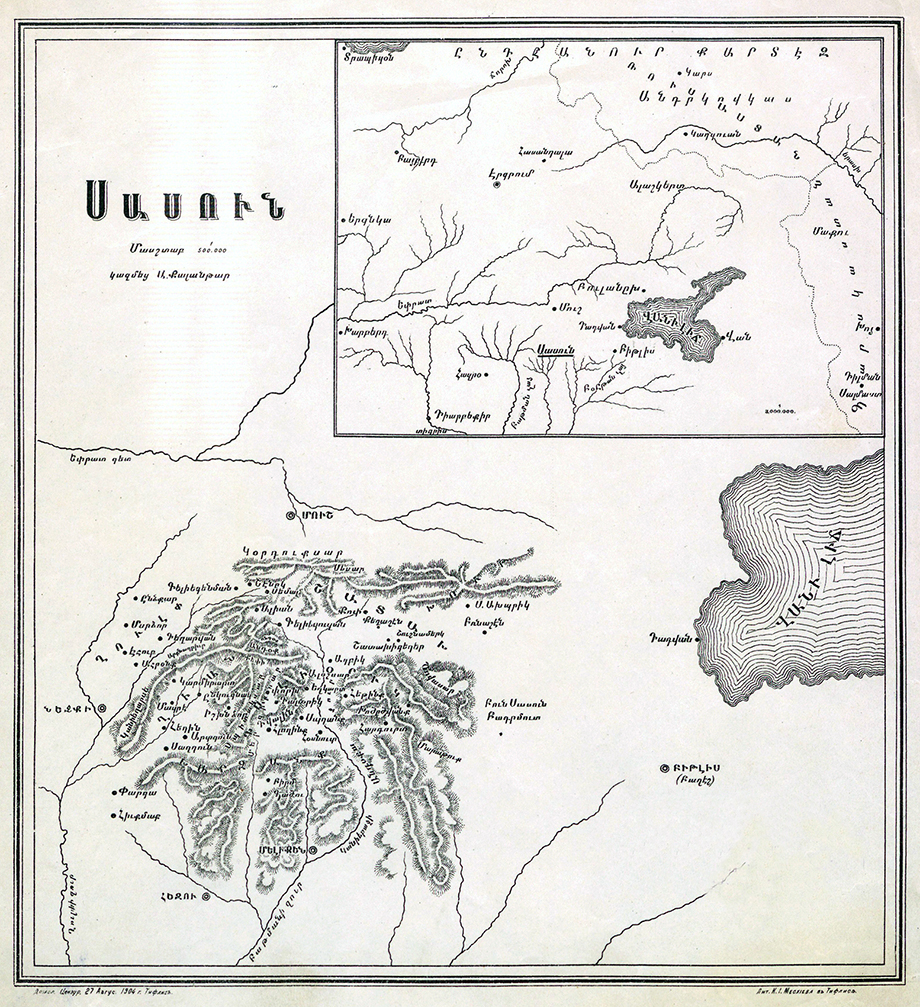

Administrative Divisions of Sassoun

“Sassoun is a vortex of lofty mountains and deep valleys crisscrossing and interlaced, violently bisecting and cutting into each other. Like a single looming mass, the city rises above the Earth in the south of the Moush Valley, about halfway up the Taurus Mountains. All the way from Moush to Sassoun, the road winds around mountains that crowd together and rising on top of each other. The road leads travelers up the flanks towards the blue sky, up towards the Dzirngadar summit, then down into a large valley, then up and down again, past more hills and summits. Every time a traveler turns a corner, new gorges, new hills and mountains, and new valleys appear before him in an endless procession.” [1]

In antiquity, the historical geographic region of the highland of Sassoun was part of the Armenia’s Aghtsnik (known as Alzini or Alshini in Urartian and Assyrian cuneiform inscriptions) and Darouperan provinces [2]. The earliest mention of Sassoun is in Assyrian cuneiform inscriptions, in which the city is called “Sassou” [3]. Ashkharatsuyts (Guide to the World, 7th century), often ascribed to Anania Shirakatsi (Ananias of Shirak), mentions “Sanasoun” as one of the ten districts of the Aghtsnik Province of Greater Armenia [4]. The westernmost regions of Sassoun were located in the Asbagounik District of the Darouperan Province [5].

Geographically, Sassoun is nestled in the Taurus Mountains, near the upper reaches of the Batman River. It is adjacent to Siirt in the east; Ginj in the west; the valley of Diarbekir in the south; and the Moush Valley in the north. The northern sections of Sassoun approach the Gortouk Mountains, its central sections are located in the heights of the Dalvorig Mountains, and its southern sections are in the shadow of the Kharzan Mountains. To the northeast of Sassoun are the Khout Mountains; to the east is Mount Dzovasar, with its wide flanks; and to the south-east the summit of Mount Maratoug (Mount Maruta) rises into the clouds [6].

In the early 20th century, much of the highland of Sassoun was administered as part of one of the Ottoman Empire’s six eastern provinces, namely Bitlis. Different parts of Sassoun were incorporated into three different districts within the province – Modgan (including Khoush-Prnashen), in the east, was part of Bitlis Province; central Sassoun (Shadakh, Kavar, Hazo-Kabeljoz) was part of Moush Province; and western Sassoun (Khoulp-Khiank and Dalvorig) was part of Ginj Province. Some scholars also consider Kharzan to be part of the historic territories of Sassoun. Administratively, Kharzan was part of the Sghert District within Bitlis Province [7].

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the above-outlined areas of Sassoun consisted of 500-550 centers of population, of which 200-250 were either exclusively Armenian-populated, or were of mixed population [8]. Historian Remon Kevorkian, using data obtained from the Armenian Patriarchate’s 1913-1914 census, calculates that on the eve of the Genocide, there were 183 Armenian-populated towns or villages, with a total population of 29,702 Armenians, spread across the following areas of Sassoun – Hazo-Kabeljoz, Psank, Khiank, Khoulp, Dalvorig, Shadakh (Dzovasar), Modgan, and Khout-Prnashen [9].

From the 8th to the 18th centuries, Sassoun was included in the Sassoun Prelacy, and often produced prelates for the Prelacy (with its seat at the Holy Apostles Monastery in Moush). In the early 19th century, when the district’s administrative center was moved to Sghert, The Sassoun Prelacy was also moved to Sghert, and was renamed as the Sghert Prelacy, with jurisdiction over the Sassoun District of the Moush Province (the future Province of Bitlis), as well as the areas of Sghert, Shirvan, and Kharzan of the Sghert District, the Ginj District, and the areas of Leje, Slivan, Derig, Bsherig, and Hazro of the Diyarbakir District. In 1865, the northern areas of Sassoun were transferred to the jurisdiction of the Moush Prelacy [10].

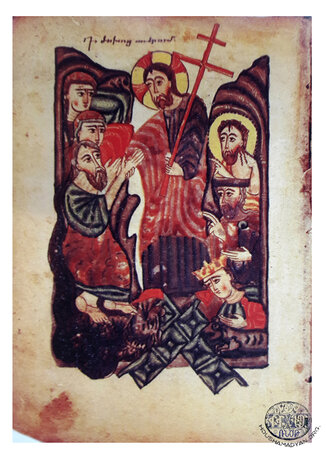

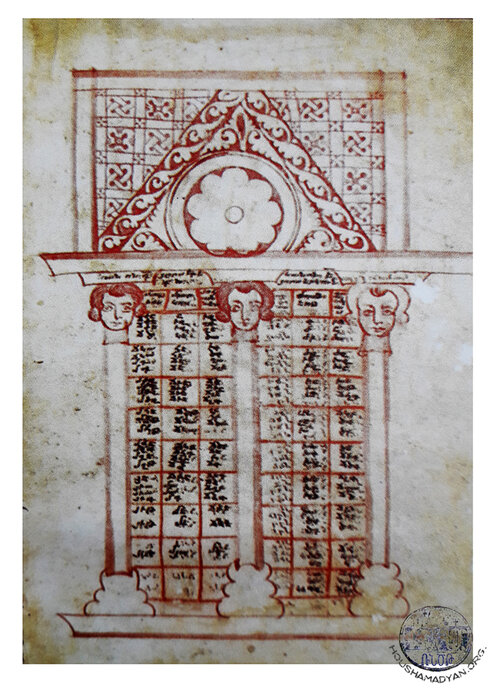

1) Illustration, date: 1507, Gospel from the Aghperig (or Vantir) monastery. Illustrated by: Krikor the monk. Currently kept in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, manuscript № 5178 (Source: A. Kevorkian, Anonymous Armenian Miniaturists, Yerevan, 2005)

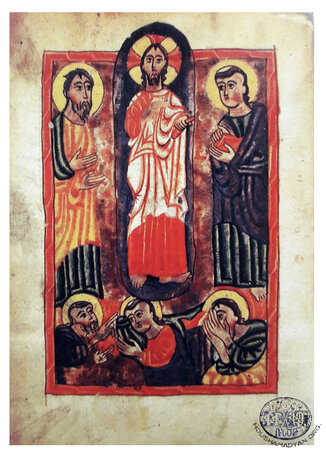

2) Illustration, date: 1507, Gospel from the Aghperig (or Vantir) monastery. Illustrated by: Krikor the monk. Currently kept in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, manuscript № 5215 (Source: A. Kevorkian, Anonymous Armenian Miniaturists, Yerevan, 2005)

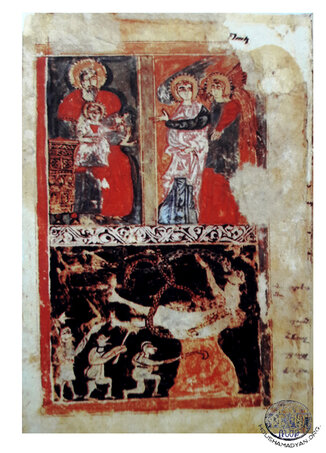

3) Illustration, date: 1490, Gospel from the Yeghrtoud (Saint Hovhannes) monastery. Illustrated by: Stepanos. Currently kept in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, manuscript № 4766 (Source: A. Kevorkian, Anonymous Armenian Miniaturists, Yerevan, 2005)

Thus, by the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, in terms of the administrative divisions of the Moush Province, the Sassoun District, as well as Khoulp-Khiank and Dalvorig, which were part of the highland of Sassoun but also part of the Ginj Province, were included in the Daron (Moush) Archbishopric of the Istanbul Patriarchate. Modgan and Khout-Prnashen were under the jurisdiction of the Paghesh bishopric [11]. Some of the southern areas of Hazo-Kabeljoz, alongside the villages of the Kharzan District of the Sghert Province, fell under the jurisdiction of the Sghert Bishopric [12].

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, throughout the 183 Armenian-populated towns and villages of Sassoun, there were 153 active or abandoned Armenian churches, and 10 monasteries. Specifically, in the smaller Sassoun area (Hazo, Psank, Khiank, Khoulp, Dalvorig, Dzovasar, and Khout-Prnashen), there were 127 churches and six monasteries; and in Modgan, there were 26 churches and 4 monasteries [13].

The Monasteries of Sassoun

Sassoun was home to scores of monasteries and pilgrimage sites – Prophet Madin, Atania, Saint Aghperig, Saint Teotoros, Saint Hovhannes, Maratoug, Hretsvar, Kistevar, Karasoun Mangounk, Saint Varvar, Saint Sarkis, Holy Virgin, Saint Kevork, Holy Cross, Meghok Kar, Saint Hagop, etc.

By late 19th century and the early 20th centuries, only a few of the above-mentioned sites were still standing. The others had been abandoned, and many of them were in ruins. These ruins became new pilgrimage sites for Armenians of Sassoun, who held religious ceremonies there on special occasions, namely on pilgrimage days.

Below, we present some of the more noteworthy monasteries of Sassoun in detail –

Aghperig Monastery (in service)

The Aghperig Monastery (also known by the names of Aghprig, Aghperga, Aghpurig, and Vantir) was located in the Khout district of Sassoun. “It was built in a gorge, in the side of a mountain. On three sides, it was surrounded by the steep Khacharach Mountain, and on the right or southern side it had a view of Prnashen and the small Tavta Field [14].”

The name of the monastery originated with one of the springs flowing in its lands. The waters of this spring were said to have healing powers. According to tradition, the monastery was founded in the first century by Saint Thaddeus. Consequently, the aforementioned spring was also known as the Spring of Saint Thaddeus [15]. It is believed that Saint Thaddeus dipped one of the nails used to crucify Christ into the spring, after which the spring’s waters gained their miraculous properties. The locals called the spring Srpachur (holy waters). They considered it a sin to spill even one drop of the spring’s water onto the ground [16].

The cathedral of the monastery was built in the 9th century. The monastery compound consists of the cathedral, the chapel, a courtyard, and several connected churches/shrines (Holy Virgin, Holy Savior, Saint Garabed, Saint Sdepanos, etc.). In the late middle ages, defensive walls were built around the compound.

Contemporaries described the architecture of the monastery as “fort-like,” and the main chapel was described as “beauteous” [17]. One of the descriptions of the monastery written in the 20th century reads – “The Aghperig Monastery is an extremely disharmonious and primitive structure. It is dark under its low ceilings. It is damp and mysterious. It inspires awe in visitors. Aside from the white steeple built in the traditional Armenian style, which grandly dominates the monastery compound, the buildings don’t possess any particular material or aesthetic qualities. The main cathedral and the chapels are built according to the same plans, as are the monks’ cloisters and the approximately 70 rooms available for visitors, most of which are in ruins and are uninhabitable. The cathedral’s main door opens onto the square nave. The threshold is a rough stone that has been hewn even more roughly into shape. The door is made of strong wood, probably ebanos… The door frame is small and low. The light that seeps into the cathedral through the narrow glass windows barely illuminates the altar and the chancel. The transepts and the nave are lost in darkness. The walls of the crossing are built of roughly-carved stones, leading unevenly to the transepts” [18].

A fragment of the True Cross was kept at the monastery. It was known was kordzel-harouyts [granter or requests] [19].

Prior to the Armenian Genocide, the Aghperig Monastery was also home to a boarding school, mostly attended by orphaned children [20].

In 1899, the monastery was attacked by Kurds. The abbot, Father Ghazar, was killed. His successor, Father Zacharia Avdallian, was killed in another Kurdish attack, in 1908 [21]. In 1914, the abbot was Father Khachadour. Alongside the students of the monastery’s school and the other members of the order, he was killed during the Armenian Genocide [22].

The church complex of the village of Komk. These are most probably the ruins of Saint Peter the Apostle Monastery (it was also known as Madnevank, Madin-Arakyal, Madin Arakelo, Saint Peter of Jgout, and the Komats Monastry of Psank). It was located in the western foothills of Mount Maratoug, by the villages of Komk and Michkegh. Photographed in the 1970's. (Source:Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) collection, Troy, New York)

Saint Peter the Apostle Monastery (in service)

The Saint Peter the Apostle Monastery (also known as Madnevank, Madin-Arakyal, Madin Arakelo, Saint Peter of Jgout, and the Komats Monastry of Psank) was one of the most renowned monasteries of Sassoun. It was located in the western foothills of Mount Maratoug, on the “stony flank of a conical hill,” between the villages of Komk and Michkegh [24].

Simeon Lehatsi [Simeon the Pole], who visited the monasteries of Western Armenian in the early 17th century, reported that “One Monastery was Madnevank, where the finger and many other relics of Peter the Apostle are kept, which were brought to this site in Sassoun from Rome, and where a monastery was built, and named Madenvank [the Monastery of the Finger]” [25].

According to local legend, the Apostle Peter had appeared to the mayor of the Komk village, who was a great sinner, and had given him his little finger, instructing him to build a monastery in the area to house this relic [26].

The monastery was founded in the 9th century [27]. The main church was the oldest surviving building, built in the 9th or 10th centuries. For its beauty, locals called it Bouke Jennete [“corner of heaven”] in Kurdish. A chapel dedicated to the Holy Virgin was located on the monastery grounds [28].

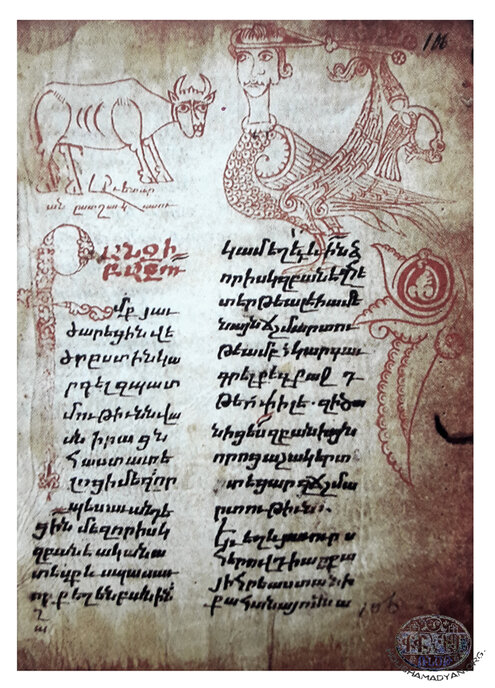

1) Date: 1242, Gospel, Saint Garabed monastery. Illustrated by: Vartan. Currently kept in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, manuscript № 3528 (Source: A. Kevorkian, Anonymous Armenian Miniaturists, Yerevan, 2005)

2) Date: 1272, Gospel, Daron region. Illustrated by: Garabed, Giragos. Currently kept in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, manuscript № 284 (Source: A. Kevorkian, Anonymous Armenian Miniaturists, Yerevan, 2005)

In the middle ages, the title of abbot was a hereditary privilege, and the monastery was the seat of the prelates of the Sassoun Prelacy [29]. The monastery was rich in its holdings. “It had more than 200 parish villages, large tracts of farmland, orchards, fields, and grasslands, which were all cultivated or served as grazing lands for the hundreds of cattle and sheep that the monastery kept. The monastery also possessed a large amount of movable assets, particularly the steel shield of Vartan Mamigonian, which was preserved with great care, in its container, in the monastery’s vaults” [30].

Pilgrimages to Madnevank were undertaken in the late autumn or the months of May, on the holidays of Easter, Vartavar (Transfiguration of Christ), and the Feast Day of the Holy Virgin. The number of pilgrims reached the thousands [31].

In the early 20th century, the monastery was still functioning, alongside its school. The abbots were Father Bedros Asdvadzadourian and Father Sdepan Baghdasarian [32].

Saint Atanakines Monastery (in service)

The Saint Atanakines Monastery was located in the Shadakh area of Sassoun, near the village of Shoushnamerg. The monastery was built of thatched stone, and was surrounded by forests. According to legend, the monastery was built by Gregory the Illuminator in the 4th century.

The monastery was abandoned in the late 1860s. In 1886, it was partially renovated, but was once again abandoned in the mid-1890s after the Hamidian Massacres [33].

The monastery was one of the most beloved pilgrimage sites and gathering sites of Sassountsis. Customarily, the monastery’s pilgrimage day coincided with the Feast of the Ascension [34].

Saint Gononos Monastery (in service)

The Saint Gononos Monastery was located in the Hazo-Kabeljoz area, near the village of Norashen.

Manuel Mirakhorian, who traveled across the Armenian-populated provinces of the Eastern Ottoman Empire in 1883, provides the following description of the monastery – “The Saint Gononos Monastery is surrounded by mountains and hills on three sides. It has clean air and plenty of clean water, as well as orchards of mulberry, fig, and pomegranate trees, which adorn and beautify the fields around it. The monastery building is beautiful, and gives visitors the impression of a large crib. The date of the monastery’s construction remains unknown to me, despite my best efforts to discover it.

“On the wall of the church located on the left side of the monastery gates is the tomb of Saint Gononos. It is a plain tomb, visited by Armenian, as well as Kurdish pilgrims. The Kurds call it the tomb of “Sheikh Eomer,” and they are granted a special area in the monastery to pray. There is also an area where the insane are brought, and are restrained using special iron chains. After remaining enchained for a few days, they are thought to have been cured, and are released.

“In the southern corner of the church is a mound of dirt, rising to a height of about a meter, and large enough for a man to sit. It is said that ‘the chief of devils’ was buried there, ‘condemned to chains and imprisoned by Saint Gononos.’

“Once, the monastery’s lands included more than 100 prosperous villages, but now that territory has been greatly reduced. The monastery has jurisdiction barely over 20 parish villages. The populations of the others have emigrated or have scattered.

“The Saint Ganonos Monastery is under the jurisdiction of the Sghert Prelacy, always has one priest and one friar or abbot, and a few heads of cattle or sheep, which serve to feed the Kurdish guards and the 3-4 field hands the monastery has.” [35]

On the eve of the Genocide, the abbot of the monastery was Father Nerses Rshdouni [36].

Holy Virgin Monastery of Marouta or Maroutavank (abandoned)

The Holy Virgin Monastery of Marouta (also known as Maroutavank, Monastery of the Supreme Virgin of Marouta, Saint Maratoug Monastery) was located on the summit of Mount Marouta, at an altitude of 2,967 meters [37].

According to the Sasna Dzrer [Daredevils of Sassoun] epic, Maroutavank was built by Sanasar and Baghdasar, and was then rebuilt by Tavit, who also established the monastery’s order and defended it from raiders. Thus, Maroutavank became the holy site commemorating the mythical heroes of Sassoun, whose blessings were sought for all endeavors [38].

The monastery had a small, single-nave church, built on a square plane, surrounded by a wall of unpolished stones [39].

By the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the monastery was abandoned and in ruins. Only one of the chapels remained standing [40].

Holy Virgin Monastery or Khodzodzvank (abandoned)

This monastery was located near the Khodzodzvank village of the Kavar (Dzovasar) area. As of the early 20th century, the church, built of thatched stone, was standing and serving as the church of the Khdzodzvank village [41].

Holy Virgin Monastery of Sousants (abandoned)

The Holy Virgin Monastery of Sousants (also known as Sousants Monastery or Zozgants Monastery) was located near the Iritsank village of the Shadakh area, on the left bank of the Sousana River, in the northern foothills of Mount Dzovasar. By the early 20th century, the monastery had been abandoned. It was a pilgrimage site for the Armenians of Shadakh [42].

Holy Virgin Monastery of Hazo (abandoned)

The Holy Virgin Monastery was located in the east of the Hako area, near the villages of Asi, Sghound, and Hrork. The monastery was abandoned in the late 19th/early 20th centuries, by which time its structures were already in ruins [43].

Saint Kevork Monastery or Karavank (abandoned)

The monastery was also known as Karavank. It was located in the Upper Kharzan area, near the villages of Hosner and Karavank. The monastery was abandoned by the early 20th century [44].

Saint Kevork Monastery of Entskar (abandoned)

The Saint Kevork Monastery of Enstkar was located in the Khoulp area, near the village of Entskar. By the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the monastery was no longer functioning, but its buildings were still standing. The monastery’s church was a single-nave structure, with two arched altars. The area right outside of the church was paved with flagstones. Inside the church was the grave of a saint, marked with a marble tombstone, right across the pulpit.

The monastery was a renowned pilgrimage site for the Armenians and Kurds of Sassoun, who spared no efforts preparing for their pilgrimage. Due to the participation of numerous Kurds in these pilgrimages, 10-12 police officers would dispatched from Pasour on pilgrimage days to ensure the safety of the large crowds [45].

The Prophet Yeghia [Elijah] Monastery (abandoned)

The monastery was located in the Khyank area, near the village of Hegh. It was a well-known pilgrimage site, and the customary day of pilgrimage was the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. By the early 20th century, the monastery had been abandoned, with only the church building still standing, and described as being “in good condition, with an arched roof” [48].

Monastery of Saint Thomas the Apostle (abandoned)

The Monastery of Saint Thomas the Apostle, or the Saint Touma Monastery, was located near the Khodz village of the Dzovasar area. By the early 20th century, the monastery was abandoned. Only the church, built of thatched stone, was still standing, “in good condition with its arched roof” [48].

Saint Hagop Monastery (abandoned)

It was located near the Saghdoun village of the Khiank area, on Mount Gebin. By the early 20th century, it was abandoned [49].

Khnad Monastery (abandoned)

It is mentioned by Hamazasb Vosgian, as one of the “ancient monasteries” of Sassoun. No other information is available [50].

Saint Garabed Monastery (abandoned)

The monastery was located near the community of Shenisd in the Khout area. It was abandoned by the early 20th century. It once had “large structures of architectural significance” [51].

Kamadoun Monastery (abandoned)

The monastery was located near the Saint Gononos Monastery, to the east of the Norashen village. By the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the monastery as abandoned, and its structures were in ruins. The main church had been built of polished stones [52].

Jrents Monastery (abandoned)

The Jrents Monastery was located near the Hroud village in the Upper Kharzan area. The main chapel of the monastery was unique in its size and beauty, with its arched roof and columns. The monastery was in ruins by the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

Saint Sdepanos Monastery (abandoned)

The monastery was located near the Keghrvan village of the Khoulp area. It was abandoned by the late 19th/early 20th centuries. The main church was still standing, in good condition, with its arched roof, and was still used by the locals for religious ceremonies [54].

Saint Teotoros Monastery (abandoned)

The monastery was located near the Shenig community of the Shadakh area. It was built of stone, but it ceased functioning by the start of the 20th century.

The Churches and Holy Sites of the Communities of Sassoun

In virtually every Armenian-populated population center of Sassoun, there were active or defunct Armenian churches, monasteries, or other holy sites and pilgrimage sites.

Here, we present the names of the churches, monasteries, and other religious sites in each of those communities, as well as the names of serving clergy. The information was obtained from the Armenian Patriarchate’s censuses and surveys organized in 1878, 1902, and 1913-1914. That information was complemented by other data and sources [55]. Villages for which serving clergy is not mentioned were served by clergy from nearby villages where more than one clergyman was employed.

The demographic information provided here is obtained from the 1913-1914 census conducted by the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul [56].

Towns and villages have been categorized by regions – “True” Sassoun (Verin Kavar, Kavar (Dzovasar)); Shadakh; Psank, Kabeljoz (including the towns and villages of Maratoug and Upper Kharzan); Hazo; Dalvorig; Khiank; Khoulp; Khout-Prnashen; and Modgan [57]. Information is provided only for Armenian population centers for which we could find pertinent records in the sources available to us.

Verin Kavar [58]

- Gelyeguzan (143 households, 1,025 Armenians): Saint Toukhmanoug (partly built of wood); Saint Sarkis (in ruins, pilgrimage site); Saint Giragos (in ruins); Saint Garabed (in ruins). In 1915, the village was ministered by Father Toros Mouradian and Father Arakel Der-Kachian.

- Shenig (70 households, 690 Armenian): Holy Virgin (built of wood, renovated); Saint Kevork (renovated); Unnamed church (in ruins); Saint Maryam (in ruins); Saint Teotoros (built of stone, dilapidated). In 1915, the village was ministered by Father Boghos Vartanian.

- Semal (81 households, 889 Armenians): Saint Kevork (built of stone, renovated); Saint Hripsimyants (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins); Dzidzernagavank (in ruins). In 1915, the community was ministered by Father Garabed Boghosian.

- There are accounts of the ruins of a church in the Alyank community (72 households, 566 Armenians).

Kavar (Dzovasar)

- Aghpi (118 Armenian households): Saint Toros (a stately ancient structure, built of thatched stone); Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, dilapidated); Unnamed church (in ruins). In 1915 the community was ministered by Father Hovhannes Simonian and Father Baghdasar.

- Hetink (60 Armenian households): Saint Sarkis (built of thatched stone, ancient, standing); Saint Mardana (built of thatched stone, ancient, standing); Khachkars (Armenian stone stelae).

- Khan (13 households, 114 Armenians): 3 churches (in ruins).

- Archonk: Saint Karasoun Mangounk (built of stone). The community was ministered by Father Mgrdich.

- Arkig (15 households, 110 Armenians): Two churches in ruins, which had become pilgrimage sites for the local population.

- The Khodzodzvank community of the region was home to the Holy Virgin, also known as the eponymous Khodzodzvank Monastery. There are also accounts of two pilgrimage/holy sites in the community.

- The following communities were each home to the ruins of one church – Pozegank (2 households, 12 Armenians); Dzargank (Saregan); Hargourk, Jakhergank (2 households, 10 Armenians); Maghenk (8 households, 58 Armenians); and Mterpank (3 households, 16 Armenians).

Shadakh

- Keghashen (44 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (built of thatched stone, ancient); Saint Giragos (in ruins); Saint Talile (in ruins). The village had a cemetery containing a number of khachkars.

- Kermav (Avkerm) (46 Armenian households): Saint Toukhnamoug. In 1915, the community was ministered by Father Karekin.

- Iritsank (17 Armenian households): Holy Virgin Monastery (built of earth); Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Shoushnamerg (32 Armenian households): Saint Choukhtagner (in ruins); Saint Minas (in half-ruins) [59].

- Dapeg (34 Armenian households): Holy Virgin the Supreme (in ruins, ancient).

- Kop (52 Armenian households): Saint Sarkis (in ruins) [60]. In 1920, the community was ministered by Father Karekin.

Psank

Sources indicate that on the eve of the Genocide, there were at least a score of small and medium-sized Armenian-populated communities throughout Psank. The area was ministered by Father Avedis Der-Avedisian, Father Sarkis, and Father Arakel. The Armenian-populated communities of Psank included:

- Peloyenk (5 households, 52 Armenians): Saint Varvara (in ruins).

- Pvi (2 households, 10 Armenians): Saint Sarkis Mouradadour [granter of wishes] (built of thatched stone, standing); Sheghtar (holy site).

- Komk (20 households, 160 Armenians): Holy Cross (in ruins); Holy Virgin (in ruins); Saint Karasoun Manoug (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins). In 1915, the village was ministered by Father Tavit Yeritsian.

- Talhor (10 households, 75 Armenians): Saint Dghamanoug (in ruins).

- Tarouk (16 households, 175 Armenians): Saint Kevork (built of thatched stone, standing); Saint Simeon (built of thatched stone, standing); Holy Cross (in ruins).

- Khntsorig (27 households, 242 Armenians): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, in ruins, pilgrimage site).

- Gornges (7 households, 35 Armenians): Saint Kevork (in ruins).

- Marsto (11 households, 102 Armenians): Holy Cross (standing).

- Michkyugh (43 households, 430 Armenians): Saint Kevork (standing, pilgrimage site).

- Mgtink (25 households, 276 Armenians): Saint Sarkis (according to other reports, called Holy Virgin [61]; built of thatched stone, standing).

- Chrtnig (23 households, 180 Armenians): Saint Kevork Vishabasban [dragon slayer] (in good condition, with an arched roof).

- Psank (11 households, 112 Armenians): Saint Sahag (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Kashkshenk (11 households, 83 Armenians): Holy Cross (in ruins in 1902, rebuilt by 1913).

- Kistagh (4 households, 20 Armenians): Saint Kristapor (in half-ruins).

- The village of Kacharink (16 households, 162 Armenians) was home to a church with an arched roof, and in good condition.

- Ruins of unnamed churches were also found in the Armenian-populated communities of Tatank (6 households, 60 Armenians); Tachpatrig (5 households, 45 Armenians); Havgounk (26 households, 125 Armenians); Pshoud (9 households, 65 Armenians); and Krtamank (9 households, 45 Armenians).

Upper Kharzan and Maratoug Area

- Arvdots (6 households, 42 Armenians): Saint Kevork (built of thatched stone, standing).

- Ardzvik (35 households, 325 Armenians): Saint Kevork (built of thatched stone, standing); Saint Daniel (in ruins, ancient monastery).

- Patermoud (25 households, 200 Armenians): Saint Kevork (standing, built of thatched stone); Holy Cross (in ruins); Holy Savior (in ruins). In 1915, the community was ministered by Father Mgrdich Mardirosian.

- Kedgits (3 households, 27 Armenians): Saint Matranagos (in ruins).

- Koshag (5 households, 30 Armenians): Saint Giragos; 2. Saint Hagop (in ruins).

- Iritsank (3 households, 18 Armenians): Saint Kevork (built of thatched stone, standing).

- Khasopi (7 households, 42 Armenians): Saint Sarkis (in ruins).

- Khocharenk (9 households, 54 Armenians): Saint Sahag (built of thatched stone, standing; Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Gorov (5 households, 34 Armenians): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, in ruins).

- Hatni (Hatenk) (4 households, 30 Armenians): Saint Garabed (built of thatched stone, previously a monastery).

- Hroud (10 households, 60 Armenians): Holy Virgin (previously a monastery); Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Shigalenk: Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone).

- Pirshenk (15 households, 155 Armenians): Marouta Holy Virgin Monastery (pilgrimage site, in good condition, with an arched roof); Kach Moushegh [Moushegh the Bold] Monastery (in good condition, large, with an arched roof).

- Aside from the above-mentioned communities, there are reports of ruins of unnamed churches in the Armenian-populated villages of Arektem (4 households, 21 Armenians); Komarder (3 households, 16 Armenians); Talartsor (7 households, 35 Armenians); Gourter (Gortis) (7 households, 45 Armenians); Hregonk (5 households, 23 Armenians); Vartnots (5 households, 35 Armenians); and Dnked (16 households, 200 Armenians).

Hazo Area

The town of Hazo- Kabeljoz in Hazo (106 households, 742 Armenians) was the administrative center of the Sassoun District. The town was home to two active churches, namely the Holy Cross Church (standing, built of thatched stone, with an arched roof) and the Kach Moushegh [Bold Moushegh] Church (standing, built of thatched stone, with an arched roof). The town was also home to the ruins of two unnamed churches. In 1902, the Hazo area was ministered by Father Hagop. By 1913, the area had six serving clergymen.

- Gogh (32 households, 200 Armenians): Saint Nshan (built of thatched stone, standing, pilgrimage site).

- Gousked (66 households, 610 Armenians): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, ancient, standing).

- Norkyugh (Kontenou) (14 households, 139 Armenians): Saint Kevork (standing); Saint Sdepanos (in ruins).

- Norashen (3 households, 15 Armenians): Monastery of Saint Gononos (in service, standing); Kamadoun Monastery (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Aside from the above-mentioned sites, there are reports of ruins of unnamed churches in the Armenian-populated communities of Ardrer (6 households, 39 Armenians); Pelav; and Komek.

According to the figures of the census commissioned in 1913 by the Moush Prelacy, the portions of the District of Sassoun included in the borders of the Moush Province (Kavar, Shadakh, Psank, and Hazo-Kabeljoz) were home to 68 functioning and abandoned churches and chapels, two functioning monasteries, and two abandoned monasteries. A total of 18 clergymen were ministering in the area (their names are not listed) [62]

Dalvorig Area

Armenian scholar A-To contended that Dalvorig was the heart of Sassoun, with its beautiful nature, impregnable mountains and gorges, unique climate, and “hardy and brave” people.

- Ardkhonk (10 Armenian households) [63]: Saint Maryam; Saint Sarkis; Saint Mardiros; Church of Khaghloghan; Saint Giragos; Church of Krashen; Church of Taghloug.

- Yeghkart (10 Armenians households): Virgin Mary (pilgrimage site).

- Ekedoun (35 Armenian households): Saint Sarkis (with an arched roof).

- Khlhovid (10 Armenian households): Saint Sarkis (in ruins).

- Hakmank (15 Armenian households): Saint Garabed (in good condition).

- Hloghink (40 Armenian households): Saint Mamas (pilgrimage site, in ruins).

- Sbeghank (11 Armenian households): Saint Marmara Monastery (ancient, built of stone, in good condition); Saint Khachtornig (dilapidated).

- Pourkh (16 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos Monastery (built of thatched stone, with an arched roof, standing).

- There are also reports of ruins of unnamed churches in the Armenian-populated communities of Tvalink (13 Armenian households); Hartk (11 Armenian households); Hosnoud (6 Armenian households), and Mzre (15 Armenian households).

Khiank Area

According to the figures of the 1913 census commissioned by the Armenian Patriarchate, the areas of Khoulp and Khiank (excluding Dalvorig) were home to 23 Armenian communities, which boasted 15 churches and an abandoned monastery. The region was ministered by 13 clergymen [64].

- Arkhount (36 households, 438 Armenians): Holy Virgin Church (ancient, magnificent); Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Ardkhonk (40 households, 368 Armenians): Saint Thomas Church [65].

- Arseg (Kherze) (13 households, 118 Armenians): Holy Virgin Church (ancient, standing).

- Pahmeta (28 households, 200 Armenians): Karasoun Manoug (ancient, built of stone) [66]; Unnamed church (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Harutyun.

- Patsi (23 households, 195 Armenians): Saint Der [Father] Moushegh (built of stone, with an arched roof, standing). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Hagop.

- Perm (110 households, 1,025 Armenians): Saint Kevork (ancient, standing, built of thatched stone, with an arched roof); Saint Sarkis (ancient, standing, built of thatched stone, with an arched roof); Holy Virgin Church (ancient, built of thatched stone, in ruins); Holy Savior (ancient, built of thatched stone, in ruins). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Arakel and Father Garabed.

- Ishkhantsor (55 households, 495 Armenians): Unnamed church (standing); Unnamed church (in ruins). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Donabed.

- Heghin (45 households, 416 Armenians): Prophet Yeghia [Elijah] Monastery (ancient, standing, with an arched roof); Unnamed church (in ruins); 3. Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Saghdoun (43 households, 369 Armenians): Holy Virgin Mary (built of stone, in ruins); Saint Kevork (built of stone, standing); Saint Hagop (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Giragos.

- Sevit (11 households, 100 Armenians): Saint Mamas (built of stone, pilgrimage site).

- Parga (50 households, 482 Armenians): Saint Giragos (built of stone, in good condition); Saint Sarkis (built of stone, in good condition). There were also another five to seven holy sites and sites of church ruins.

- The presence of unnamed churches and pilgrimage sites was also reported in the Armenian-populated communities of Krekhokh (3 Armenian households [67]) and Shmanank (5 Armenian households).

Khoulp Area

- Aharonk (55 households, 500 Armenians): Holy Virgin (built of stone, standing); Saint Yot Manoug (built of stone, dilapidated); Saint Kevork (in ruins). The community was ministered by Father Hagop Der-Hagopian (1902 and 1915) and by Father Kalousd Der-Mgrdchian (1915).

- Kazge (52 households, 476 Armenians): Saint Teotoros (ancient, built of stone); Saint Kevork (in ruins); Saint Sarkis (in ruins); Saint Gatoghige (in ruins); Saint Giragos (in ruins).

- Keghervank (50 households, 472 Armenians): Saint Sdepanos (built of thatched stone, ancient); Saint Kevork (built of wood); Unnamed church (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Ehoup (30 households, 316 Armenians): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, arched, ancient); Saint Kevork (in ruins, with a vast network of defensive walls); Saint Ardzvaper; 4. Saint Sarkis (in ruins); Saint Mangounk (in ruins).

- Untskar (100 households, 1,012 Armenians): Saint Kevork Monastery (built of thatched stone, ancient); Holy Virgin (in ruins); Holy Cross (in ruins); Saint Sarkis (in ruins). In 1915, the community was ministered by Father Daniel.

- Shoghek (22 households, 214 Armenians): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, standing); Saint Mordzako (in ruins).

- There are reports of ruins of unnamed churches in the Armenian-populated communities of Kremor (8 households, 43 Armenians) [68]; Tultav (10 households, 94 Armenians); Tyakhs, Khrouj, Gabernin, Haverk, Mashdag, and Pasour.

Khout-Prnashen

Communities of Khout

- Azrag (16 Armenian households): Holy Virgin (built of thatched wood, ancient). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Mgrdich Chopanian.

- Avark (6 Armenian households [69]): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone).

- Tapentagh (16 Armenian households): Holy Virgin; Saint Giragos (in ruins) [70].

- Kelonk (8 Armenian households): Holy Virgin (in ruins), according to other sources, called Saint Garabed [71]; Saint Hagop. In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Giragos and Father Hovhannes.

- Taghavank (25 Armenian households): Saint Kevork (magnificent; with an arched roof); Saint Sarkis (in ruins); Saint Chigrashen (in ruins). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Abraham and Father Sarkis.

- Taghventsor (6 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (in good condition) [72]. In 1902, the community was ministered by Fathre Gorun and Father Hovhannes.

- Taghvou (Tagh) (18 Armenians households): Saint Sdepanos (built of thatched stone, ancient). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Apraham.

- Lortentsor (14 Armenian households): Saint Hovhannes (in ruins). The community was ministered by Father Apraham (1902) and Father Sarkis Mkhitarian (1915) [73].

- Gor (5 Armenian households): Karasoun Manoug (in ruins).

- Hakhin (Yeghan) (9 Armenian households): Saint Echmiadzin (in ruins).

- Hntgetsor (Hintsor) (3 Armenian households) [74]: Saint Garabed (with an arched roof, in ruins).

- Mezre (Mezre-Shilk) (8 Armenian households): Saint Garabed (in ruins).

- Shen (35 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (built of thatched stone). According to other sources, the community had four churches: Saint Hagop; Saint Mardzmed; Holy Virgin; and Holy Rider of Goularna [75].

- Inner Shenisd (25 Armenian households): Holy Virgin (built of thatched stone, ancient, in good condition); Saint Toukhnamoug (in ruins); Saint Garabed (in ruins); Holy Cross (in ruins). In 1902, the community was inistered by Father Giragos and Father Hovhannes.

- Pichonk (21 Armenian households): Saint Tovmas (in ruins). In 1902, the community was ministered by Father Mgrdich.

- Pghonk (10 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (built of thatched stone, standing); Saint Garabed (built of thatched stone, partially in ruins); Saint Hovhannes (built of thatched stone, partially in ruins); Saint Karasoun Manoug (built of thatched stone, partially in ruins).

- Keyvou (7 Armenian households): Saint Zion (standing, built of thatched stone); Saint Sarkis (in ruins).

- There were other unnamed churches (several in some cases) in the Armenian-populated communities of Kordzevar (which had been emptied of Armenians); Gork, Chalakh (7 Armenian households); Rapat (8 Armenian households [76], emptied of Armenians by 1902) [77], Salachonk (5 Armenian households), and Pirivank (emptied of Armenians, according to information from 1902).

Communities of Prnashen

On the eve of the Genocide, the supreme ecclesiastical leader of the Khout-Prnashen area was Father Sarkis Sdepanian [78].

- Arouk (13 Armenian households): Saint Minas (built of thatched stone, in ruins).

- Upper and Inner Plogank (20 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (in ruins); Unnamed church (in ruins). In 1902, the communities were ministered by Father Sahag.

- Plrig (6 Armenian households): Saint Garabed (in ruins).

- Tashdatem (21 Armenian households): Saint Minas (in ruins).

- Zorava (7 Armenian households): Saint Toros (in ruins).

- Engouzig (18 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (standing); Saint Daniel (in ruins).

- Gdzank (18 Armenian households): Saint Garabed (ancient, in ruins); Saint Kevork (ancient, in ruins).

- Gosd (8 Armenian households): Holy Virgin Monastery (ancient), with its churches of Saint Talile, Saint Sdepanos, Saint Garabed, and Saint Dyarneghpayr (in ruins); Saint Tovmas (in ruins).

- Shahverti (10 Armenian households): Unnamed church (in ruins).

- Shamyank (2 Armenian households [79]): Saint Garabed (in ruins).

- Upper Shenisd (15 Armenian households): Saint Zion (ancient, built of stone, standing); Saint Kevork (ancient, built of stone, in good condition).

- Oshoud (Houshoud) (32 Armenian households): Saint Sdepanos (with an arched roof, in good condition). In 1910, the community was ministered by Father Sarkis [80].

Modgan Area

- Upper Asbencher (35 households, 526 Armenians): Saint Toukhnamoug (in good condition, with an arched roof).

- Inner Asbencher: Saint Sdepanos.

- Arpi (30 households, 400 Armenians): Holy Virgin of Anega (in good condition, with an arched roof) [81].

- Poghnoud (20 households, 300 Armenians): Holy Virgin.

- Proudk (27 households, 155 Armenians): Saint Hagop.

- Kzekh (15 households, 130 Armenians): Saint Giragos (built of thatched stone, with an arched roof, in good condition).

- Kentsou (49 households, 500 Armenians): Saint Kevork.

- Krkhou (40 households, 400 Armenians): Dernaghper Church (with an arched roof); Saint Hagopshen (with an arched roof).

- Khour (13 households, 105 households): Saint Sdepanos [82].

- Havoutagh (13 households, 55 Armenians): Holy Virgin.

- Mzouk (16 households, 188 Armenians): Saint Sdepanos (built of thatched stone).

- Mrtsank (5 households, 50 Armenians): Saint Kevork.

- Mtsou (30 households, 300 Armenians): Saint Sarkis (in good condition, with an arched roof).

- Nich (25 households, 200 Armenians): Saint Kevork (with an arched roof, in good condition); Saint Minas (in ruins) [83].

- Shen (50 households, 500 Armenians): Holy Virgin (standing, with an arched roof); Unnamed monastery (in ruins).

- Vortsenk (10 households, 90 Armenians): Saint Kevork.

- Selenter (Sghount) (30 households, 400 Armenians): Saint Hagop (in good condition); Shamonian (in good condition).

- Kashakh (27 households, 600 Armenians): Saint Hagop (in good condition, with an arched roof)

- Records indicate the presence of ruins of unnamed churches in the communities of Garp (9 households, 84 Armenians); Marmant (3 households, 11 Armenians); Meretagh (7 households, 73 Armenians); Gasab (9 households, 82 Armenians); and Chrdou.

According to the 1913 census commissioned by the Armenian Patriarchate in Istanbul, the Modgan region was ministered by two clergymen (the names are not recorded). A total of 26 active or abandoned churches were listed in the area, as well as the ruins of four monasteries [84]

Pilgrimage Customs of Sassoun Armenians

The Armenians of Sassoun adhered to the teachings of the Armenian Apostolic Church. There was not a single Catholic or Protestant Armenian in Sassoun [85]. Contemporaries described Sassoun Armenians as “fervently pious; virtuous and decent; but also very ignorant and gullible” [86]. Records show that “every year, the people of Sassoun would provide plenty of fruits, tithes, loot, animals for slaughter, and other gifts to the clergymen and monks serving them” [87]. The hundreds of monasteries, khachkars, and holy sites throughout Sassoun had been revered by the people for centuries.

The people of Sassoun enjoyed going on pilgrimages, which occupied an important place in their spiritual life. The favorite destinations for pilgrims were the five historic mountains of Sassoun, and the holy sites scattered on their flanks. The Holy Virgin Monastery was on Mount Maratoug/Marouta; the shrine of Andon the Hermit was on Mount Antog; Saint Hagop was on Garmir Jagad [Red Forehead]; the Holy Virgin was on Dzovasar; and Saint Aghperig was on Sev Sar [Black Mountain] [88]. Other destinations for pilgrims included Komats Monastery in Psank and the Saint Atanakines (Atania) Monastery of Shadakh. Large number of Sassountsis also traveled to the Saint Garabed and Saint Hovhannes (Yeghrtoud) monasteries in Moush [89].

Sassountsis believed that certain holy sites had the capacity to heal ailments or grant wishes. To wit, The Saint Kristapor Monastery of Kistagh, in the Psank area, was a destination for those suffering from abdominal pains; Saint Dghamanoug in Tarhor for infertile women; Saint Karasoun Manoug of Komats for those suffering of arthritis; Saint Hagop of Paron for those suffering from whooping cough (with the intention of drinking from the springs on the monastery grounds, which were thought to cure their ailment); Saint Varvar of Palo for young men and women seeking blessing in their search for a spouse; Saint Sarkis of Mouradadour of Pvi for all who sought to be blessed with success. Nursing mothers who had trouble lactating made pilgrimages the Holy Virgin in Khntsorets (for this reason, the holy site was also known as gatndou [milk giver]). Those who were bitten by snakes were taken to Saint Kevork Otsasban [Snake Slayer] in Chrtnets. The Holy Cross Antrsevaper [Rain Bringer] was visited by pilgrims in the month of May, to pray for rain. Sassountsis visisted Saint Kevork in Mshkegh to pray for a bountiful harvest [90].

Pilgrimages were made on predetermined days and in the appropriate seasons of the year. For example, pilgrimages to one of the favorite sites in the area, Mount Maratoug and the Maroutavank Monastery, were undertaken on the Vartavar Holiday (Feast of Transfiguration), as well as on the day of the Feast of the Cross [91]. Sassountsis from Kharzan, Hazo-Kabeljoz, Modgan, and Psank made their way to Mount Maratoug every year on Vartavar, and spent three or four days on the mountain. The number of pilgrims would be in the thousands. On the first day, a ceremony was held to celebrate vows to Big Maratoug, and on the second day, to Little Maratoug [92], during which animals were ritually slaughtered. The third and fourth days were devoted to games, dancing, and celebrations [93]. On Vartavar and other pilgrimage days, Holy Mass was held in the still-standing chapel of the Maroutavank Monastery [94].

On the Feast of the Ascension, Sassountsis made their way to the Saint Atanakines Monastery. In one description of the pilgrimages undertaken on that day, we read that Sassountsis eagerly awaited the day not only “to celebrate Christ’s ascensions and his final farewell to the world, but mainly to enjoy the aroma of the flower of life.” Almost each household would bring along a sheep to slaughter, and would undertake other preparations. On this holiday, Sassountsis would wear their best clothes, while girls and women would don their best frocks and jewelry. Entire families would make the journey to the monastery together, and the huge crowds would travel changing “Oh Saint Antanya! Aha zemer beder kezi gdank, tou zmer mourads i das?” [Oh Saint Antanya! Here we are sharing our crops with you; won’t you grant us our wishes?”].

Once within sight of the monastery, the pilgrims would cross themselves, praying “Havadam, khosdovanim kou soupr yerese” [“May I have faith in and confess to your holy visage”]. It was customary for armed men to fire their hunting rifles into the air – “thus, with the air filled with the cracks of gunshots and the hollering of the Kurds playing their games, the crowds would penetrate the narrow forest paths and eventually arrive to the site of the monastery.”

Upon arrival, each family would prepare a pit for the roasting of the ritual sacrifies, after which the celebrations would begin in earnest. “Suddenly, one would hear the beating of the dhols, the melodious sound of the zurna, and the wire of the acrobat would be strung up above the celebrants, allowing the young boys to show off their skills, in the name of Saint Garabed. Gifts would flow, the crowds would dance in circles, the Kurds would perform their dance games, with the zurnas, trumpets, and ninemninas playing in the background,” as told by a contemporary who participated in the pilgrimages [95].

During the commemoration of Prophet Elijah’s Fast, as well as on his feast day (the Sunday following Whitsunday, usually in the month of June or July), the Armenians of Khoulp-Khiank would go on pilgrimage to the Monastery of the Prophet Elijah in the village of Heghin. They would also be joined by the local Kurdish ashirets. Once every seven years, the locals would also visit the monastery on the Holiday of the Assumption of Mary [96].

An important pilgrimage site for the Armenians of Dalvorig was the Monastery of the Marapa or Marouta Hermit. It was surrounded by orchards and fruit trees. The old church had two “magnificent” chapels, surrounded by tall walnut trees. The pilgrims never dared eat the walnuts of these trees, because according to legend, any who ate these walnuts would be punished. The priest of the Sbghank village would gather the walnuts and press them into oil, for use during church ceremonies [97].

Sassountsis believed that the waters of the springs located on the grounds of monasteries had healing powers. One such spring was located on the grounds of the Atania (Saint Atanakines) Monastery. The spring was known by its Kurdish name, Ganie Maran (Spring of the Snake). A hut had been built on the site of the spring, and the waters would rise from the ground and collect in this hut/chapel. The sick would enter the hut, swim in the water, burn incense, light candles, and then fill bottles with the water of the spring to take home with them. These bottles would be wrapped in silk handkerchiefs, so that the water’s sanctity would not be contaminated by contact with the ground or other “unclean” objects [98].

There were also several fields of khachkars scattered around Sassoun. They, too, were considered pilgrimage sites by local Armenians [99].

- [1] A-To, Vani, Bitlisi, yev Erzurumi Vilayetnere [The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis, and Erzurum], Yerevan, 1912, page 119.

- [2] Vartan Bedoyan, Sassoun, Yerevan, 2016, page 19.

- [3] Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri Deghanounneri Pararan [Dictionary of Place Names of Armenia and the Environs], Volume 4: N-V, Yerevan, 1998, page 506.

- [4] The digital version of Ashkharatsuyts can be accessed online at www.digilib.am/book/62/62.

- [5] Vartan Bedoyan, “Sassoun, nra Ngarakrutyune, pnagitchnere, yev notsa Parkn ou Varke” [“Sassoun, A Description of the City, its People, and their Customs and Lifestyle”], from Araks Kragan yev Kegharvesdagan Hantes [Arax Literary and Creative Journal], Book A, Saint Petersburg, 1894-1895, pages 68-69.

- [6] G. Taroyan, Joghovurtagan Sharjumner Sassounoum [Popular Movements in Sassoun] 1890-1894, Yerevan, 1966, page 29.

- [7] Garo Sassouni, Badmutyun Daroni Ashkharhi [History of the Land of Daron], Beirut, 1956, page 370. Also see H.M. Boghosian, Sassouni Badmutyun [History of Sassoun] 1750-1818, Yerevan, 1985, page 99. Also see Vartan Bedoyan, “Sassoun…”, page 27. Between 1878 and 1914, the administrative status of Sassoun was not stable. The Ottoman authorities constantly re-drew the administrative lines of Bitlis Province and its districts, which greatly affected the status of Sassoun. This was a deliberate policy to quell this restive area that continued to defy the government’s policies.

- [8] See the “Sassoun” entry in Hayasdani yev Haragits Sherchanneri…, page 505. Also see Haygagan hamarod Hanrakidaran [Abridged Armenian Encyclopedia], Volume 4, 2003, page 346. Teotig, relying on the statistics of the 1913-1914 Istanbul Patriarchate census, counts 186 Armenian-populated communities on the eve of the Genocide, including 75 in Antog, Shadakh, Hazo, Psank, Kavar (Dzovasar), and Gousked; 50 in Khout-Prnashen and Modgan; and 61 in Ginj, Dalvorig, Khoulp-Khiank, Djabaghchour, and Manshgoud (Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and its Flock's Catastrophic Year of 1915, Tehran, 2014, page 133).

- [9] Rayond H. Kévorkian, Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du Génocide, Paris, 1992, page 59. Garo Sassouni counted 245 Armenian-populated villages, with 6,954 households, and a total Armenian population of 41,724 across the highland of Sassoun (Modgan and Kharzan included) (Garo Sassouni, Badmutyun Daroni…, page 370).

- [10] A. Alboyajian, “Arachnortagan Vijagner” [“Parish Statuses”], Entartsag Oratsuyts S. Prghcyan Hivantanotsi Hayots [Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Istanbul, 1908, page 315.

- [11] Archbishop Maghakia Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin [The Armenian Church], Istanbul, 1911, page 262.

- [12] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 129-131.

- [13] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman, pages 59-60.

- [14] Hamazasb Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere (The Monasteries of Daron-Darouperan), Vienna, Mkhitaryan Printing House, 1953, page 10.

- [15] Vijagakir Msho Arachnortagan Temin Varjaranats, Yegeghetsyats, Vanoreits, Vgayaranats, Shen yev Aver(i Tashd Msho yev Sherchagays) Madrants, Nviragan Deghyats, Pnagchutyan Avanats yev Shinits yev Yegeghetsagan Bashdoneits, Havakial esd Hrahanki Azk. Badriarkarani 1902 [Survey of the Schools, Churches, Monasteries, Institutes, Shrines (Standing and in Ruins), Holy Sites, Population Centers, and Staff and Clergy members of the Moush Prelacy, Commissioed by the Armenian National Patriarchate in 1902]. A.R.F. Boston Archives, personal documents, Personal Collection of Kagham Der-Garabedian (Dadrag), page 157.

- [16] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 126-137.

- [17] Kegham Der-Garabedian (Msho Kegham), “Nviragan Oukhdadeghiner” [“Holy Pilgrimage Sites”] commentary, Masis, Istanbul, 1903, N. 27, page 423.

- [18] A. Safrasdian, “Khoyt-Prnashen Kavarnere: Oughevoragan Deghegakroutyunner” [The Regions of Khoyt-Prnashen: Travel Information”], Hantes Amsorya [Monthly Digest], Vienna, 1933, Year 48, January-February, page 70. Also, Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, pages 11-12.

- [19] Ibid.

- [20] Bedoyan, Sassouni yev Daroni Badmashkharhakragan Deghakroutyune…, page 47; Aghprig Vank entry, Soviet Armenia Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, Yerevan, 1975, page 251.

- [21] A. Safrasdian, “Khoyt-Prnashen…”, Hantes Amsorya [Monthly Digest], Vienna, 1933, Year 48, September-October, page 620.

- [22] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 127.

- [23] Y. Garabedian, Sassoun: Azkakgragan Nyuter [Sassoun: Demographic Commentaries], Yerevan, 1962, page 119.

- [24] “Masis”, 1903, N. 27, page 423; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 247.

- [25] Simeon Lehatsi, Travel (quotes by Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 248).

- [26] Ibid.

- [27] “Masis”, 1903, no.27, page 423.

- [28] Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 248. According to Father Mgrdich Mouradian, the monastery was built in the 12th century (Mgrdich K. Mouradian, “Avantutyunner Sasno Oukhdadyats Masin” [“Traditions of Sassoun’s Pilgrimage Sites”], Hayasdani Gochnag [The Armenian Clarion], Year 22, N. 7, February 18, 1922, page 237).

- [29] Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 248.

- [30] Ibid., page 250.

- [31] Mouradian, “Avantutyunner Sasno…”, page 237.

- [32] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 136.

- [33] “Masis”, 1903, N. 27, page 424; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, pages 9-10.

- [34] S. M. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkhar [The Land of Western Armenia], New York, 1947, page 449.

- [35] Manuel Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevorutyun i Hayapnag Kavars Arevelyan Dadjgasdani [Descriptions of travels in Armenian-populationed Regions of Eastern Anatolia], Istanbul, 1884, pages 73-75 (the book may be accessed via the digitized archives of the Matenadaran at www.digilib.am).

- [36] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 131.

- [37] Krisdonia Hayasadan [Christian Armenia] Encyclopedia, Yerevan, 2002, page 711.

- [38] Ibid.

- [39] Ibid.

- [40] “Masis”, 1903, N. 28, page 441; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, pages 258.

- [41] “Masis”, 1903, N. 28, page 441.

- [42] Bedoyan, Sassouni yev Daroni Badmashkharhakragan Deghakroutyune…, page 29.

- [43] Ibid., page 57 (the author also details other superstitious beliefs connected with the monastery).

- [44] “Masis”, 1903, N. 28, page 441; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 87.

- [45] Bedoyan, Sassouni yev Daroni Badmashkharhakragan Deghakroutyune…, page 67.

- [46] “Masis”, 1903, N. 28, page 441; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 91.

- [47] V. A. Bedoyan, Sassouni Parpare [The Dialect of Sassoun], Yerevan, 1954, page 183.

- [48] Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, pages 131-132.

- [49] “Masis”, 1903, N. 28, page 441; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 260.

- [50] Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 132.

- [51] “Masis”, 1903, N. 28, page 441; Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankere, page 134.

- [52] Bedoyan, Sassouni yev Daroni Badmashkharhakragan Deghakroutyune…, page 54.

- [53] Ibid., page 57.

- [54] Ibid., page 67.

- [55] Source of 1878 information – Devagants Arsidages, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878 t. [Visit to Armenia in 1878], Yerevan, Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic Academy of Science, 1985, pages 48-54. Source of 1902 information – Vijagakir Msho Arachnortagan Temin Varjaranats…. Source of 1913-1914 information – AGBU Noubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 45-48 (Region of Sassoun), 59-61 (Verin Kavar, Modgan, Khiank, Khoulp); also see Kévorkian/Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman, page 477 and pages 492-496. The names of clergymen serving communities are provided by Teotig (Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan, pages 110-125). Other complementary sources include the works of historian and demographer Vartan Bedoyan, who was a native of Sassoun (V.A. Bedoyan, Sassouni Parapare…, pages 171-198; and Bedoyan, Sassouni yev Daroni Badmashkharhakragan Deghakroutyune…, pages 13-82).

- [56] AGBU Noubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff 45-48; Kévorkian/Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman, page 477 and pages 492-496; Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan, pages 110-125. When necessary, we have also used other sources, as detailed.

- [57] Names and administrative statuses of communities obtained from the Armenian Abridged Encyclopedia’s “Bitlis Province” article (Abridged Armenian Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, A-Tachoum, Yerevan, Central Publishing Office of the Armenian Soviet Republic, 1990, pages 532-535.

- [58] According to official administrative divisions, the Verin Kavar region was included in the Province of Moush. However, Verin Kavar’s geographic position leaves no doubt that it is part of the Sassoun highland.

- [59] According to figures for 1878 (Devgants, Aytseloutyun Hayasdan, page 71).

- [60] According to other information (from 1878), it was called Saint Garabed (Devgants, Aytseloutyun Hayasdan, page 71).

- [61] Bedoyan, Sassouni Parpare…, page 175.

- [62] AGBU Noubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 45-48, 59.

- [63] Numbers of Armenian households in the villages of Dalvorig are provided by A-To, for the year 1909 (A-To, Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzurumi Villayetnere, page 134).

- [64] See the list of villages included in the 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate Census (AGBU Noubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 61).

- [65] Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, Vol. 1, page 504.

- [66] Ibid., page 568.

- [67] According to figures for 1909 provided by A-To (A-To, Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzurumi Villayernere, page 136).

- [68] According to figures for 1909 provided by A-To (ibid., page 136).

- [69] According to figures for 1909 provided by A-To (ibid., page 142).

- [70] According to information from 1878, the two churches were both called Saint Garabed (Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, page 69).

- [71] Safrasdian, “Khoyt-Prnashen…”, page 613.

- [72] According to information from 1878, the two churches were both called Saint Garabed (Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, page 69).

- [73] Safrasdian, “Khoyt-Prnashen…”, page 615.

- [74] According to figures for 1909 provided by A-To (ibid., page 136).

- [75] Bedoyan, Sassouni Parpare…, page 173.

- [76] According to figures for 1909 provided by A-To (ibid., page 136).

- [77] According to V. Bedoyan, it had five churches (Bedoyan, Sassouni Parpare…, page 184).

- [78] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 126.

- [79] According to figures for 1909 provided by A-To (ibid., page 142).

- [80] Safrasdian, “Khoyt-Prnashen Kavarnere: Oughevoragan Deghegakroutyunner”, Hantes Amsorya, Vienna, 1934, Year 48, May-July, page 310.

- [81] K. Giragosian, Sassoun, Yerevan, 2010, page 174.

- [82] ] Safrasdian, “Khoyt-Prnashen Kavarnere: Oughevoragan Deghegakroutyunner”, Hantes Amsorya, Vienna, 1933, Year 47, January-February, page 148.

- [83] Giragosian, Sassoun, page 175.

- [84] List of villages included in the 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate Census (AGBU Noubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 60).

- [85] Bedoyan, Sassoun..., page 495.

- [86] “Sassoun, nra Ngarakroutyune, pnagitchnere….”, page 91.

- [87] Ibid.

- [88] Bedoyan, Sassoun…, page 496.

- [89] Garabedian, Sassoun, Azkakragan Nyuter, page 119.

- [90] Father Mgrdich Mouradian, “Hretsvari Srpavayrere yev Anhayd Aghpyuri Avantoutyune” [“The Holy Sites of Hretsvar and the Tradition of the Unknown Spring”], Hayasdani Gochnag [Armenian Clarion], N. 25, June 24, 1922, page 818.

- [91] Ibid.

- [92] The Maratoug Mountain had two summits – one on the right and one on the left, which the locals called Big Maratoug and Little Maratoug, respectively.

- [93] Bedoyan, Sassouni yev Daroni Badmashkharhakragan…, page 58.

- [94] Father Mgrdich Mouradian, “Avantoutyunner Sasno Oukhdadyats Masin” [“Pilgrimage Traditions of Sassoun”], Hayasdani Gochnag [Armenian Clarion], New York, Year 22, N. 7, February 18, 1922, page 238.

- [95] A. Mikayelian, “Sassoun”, Asbarez Anthology 1908-1918, Fresno, Asbarez, 1918, pages 248-249.

- [96] Ibid.

- [97] Ibid.

- [98] Garabedian, Sassoun, Azkakragan Nyuter, page 120.

- [99] Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkarh, page 449.