Kaza of Van - Churches and Monasteries

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 12/09/18 (Last modified 12/09/18) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The administrative divisions and ecclesiastical provinces of the Van Sub-District

The Van Kaza (sub-district) was the center (merkez kaza) of the eponymous sanjak (district) and vilayet (province). Pursuant to the Ottoman administrative divisions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the sub-district comprised the City of Van (the seat of the provincial governor); villages in the immediate vicinity of the city that were under the direct rule of the governor (the Van-Dosb merkez nahiye (central cluster of villages)); and three other nahiyes – Timar (located to the northwest of Van-Dosb), Ardjag (east of Timar and Van-Dosb), and Hayots Tsor (south of Van-Dosb) [1].

According to the figures provided by the ecclesiastical authorities of Van for the 1913-1914 census commissioned by the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, the City of Van was home to 4,230 Armenian households and a total Armenian population of 22,470. The Armenian-populated areas of Van-Dosb were home to 1,592 households and a total Armenian population of 9,614. The Ardjag Nahiye was home to 22 Armenian-populated settlements, with a total of 1,013 households and an Armenian population of 6,679. The Timar Nahiye was home to 40 Armenian settlements, with a total of 2,525 households and an Armenian population of 15,411. The Hayots Tsor Nahiye was home to 30 Armenian settlements, with a total of 1,383 households and an Armenian population of 8,482. Thus, on the eve of the Genocide, the Van Sub-district as a whole was home to 10,743 Armenian households and a total Armenian population of 62,656 [2]

A litany of ecclesiastical provinces operated within the Van Sub-district. The City of Van, the villages of Van-Dosb, the entirety of the cluster of villages of Ardjag, and a portion of the villages in Timar were under the jurisdiction of the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate, within the borders of the Van Archdiocese. Some of the Armenian-populated villages of Timar fell under the jurisdiction of the monastic diocese of Lim-Gdouts, while the villages of Hayots Tsor fell under the jurisdiction of the Aghtamar Catholicosate [3].

Beginning in the 10th century, the diocese of Van was known as the Varakavank Diocese. From the beginning, the abbotship of the Varakavank Monastery and the leadership of the diocese were almost inseparable offices – the abbot of the monastery was also the prelate of the diocese. Throughout the centuries, the diocese was alternately subject to the spiritual jurisdiction of the Aghtamar and Echmiadzin catholicoses, and then, in 1828, it became subject to the jurisdiction of the Istanbul Patriarchate. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the diocese of Van and the adjacent dioceses of Gdouts and Hekyar covered almost the entire territory of Van Province [4].

On the eve of the Genocide, Father Yeznig Nergararian was the acting prelate of the Van Diocese [5].

The diocese of the Lim Monastery first appeared in records in the 14th century. Until 1898, it constituted a separate abbotship, sometimes under the jurisdiction of the Aghtamar Catholicosate. In 1898 it was merged with the Gdouts Abbotship [6].

Gdouts Monastery and its abbotship were established by monks who had separated from the Lim order, in the 15th century (or 16th century, according to some sources). In 1828, authority over Gdouts was granted to the Van Prelacy, and in 1898 the monastery merged with the Lim abbotship. In 1904, by decision of the Central National Committee, the Lim-Gdouts monastic territory was merged with the Van Prelacy [7].

By the early 20th century, the once-influential Aghtamar Catholicosate had already relinquished many of the dioceses under its authority to the Istanbul Patriarchate, and as a result, had lost much of its significance. After the death of Catholicos Khachadour Shiroyan, the seat of Aghtamar remained vacant until the Armenian Genocide, and the jurisdiction was administered by locums and a supervisory board appointed by the Istanbul Patriarchate [8].

According to the Istanbul Patriarchate’s 1904 figures, in the Van Diocese (Van-Dosb, Atilchevaz, Pergri, and Ardjesh), there were 114 churches and 25 standing (and nominally functioning) monasteries. The Lim-Gdouts (Timar) Diocese was home to 24 churches and 8 monasteries, and the Aghtamar Diocese (Gardjgan, Vosdan, Getsan, Gargar, Hayots Tsor, and Shadakh) had 193 churches and 41 monasteries [9].

Van’s Protestant Church

Van was one of the centers of Armenian Protestant presence in the Ottoman Empire. The community was established in 1872-1873, by visiting American missionaries [10]. One of the original founders, George Reynolds, led the Protestant Armenian community in the city, alongside his wife, until 1915 [11].

In Van, like elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire, the Protestant community founded educational institutions and hospitals alongside religious establishments. In Van, American missionaries supported a men’s school/college, a girls’ boarding school (which operated as a college in 1882 and from 1913 on), the American hospital (in 1911), and a coeducational boarding school (founded in 1896) [12].

On the eve of the Genocide, the Protestant enclave of the City of Van was located in the Aykesdan neighborhood. It included a meeting hall, two large school buildings, two small school buildings, an embroidery school (for girls), a hospital, a pharmacy, and four homes set aside for missionaries [13].

According to information from a survey performed in 1910, the number of Armenians who were members of Van’s Protestant community was 215 at the time of its founding. In 1910, at the time of the survey, 112 of them were still present and active, 57 had emigrated (43 of them to the United States), 34 had died, and 12 had severed their connections with the Protestant Church (by contrast, Maghakia Ormanian, in his work Hayots Yegeghetsi [The Armenian Church], published in 1911, puts the number of Protestants living in the territory of the Van Diocese at 200]) [14].

An overview of the situation of monasteries in the Van Sub-District (1870s-1914)

The Van Sub-District was home to a great number of Ottoman Armenia’s monasteries and holy sites. Experts attribute this to three factors – a) in antiquity, Van-Vasbourgan was one of the largest and most populous provinces of Armenia; b) Vasbouragan’s kings, clerical elite, and people had always been eager to build monasteries; and c) the province had been fairly wealthy, and had been blessed with relatively long periods of peace and general progress [15].

Prior to the Armenian Genocide, one could find monasteries and chapels, whether in good repair or dilapidated, virtually everywhere in Van-Vasbouragan – in the vicinity of every village, at the foot of every hillock. All monasteries and holy sites were also pilgrimage destinations dear to the locals’ hearts. Each had its own dedicated festival day, which, as a rule, corresponded with one of the major Christian holidays in the fall, spring, or summer months. On the fixed day of pilgrimage, people from both nearby and faraway villages would gather at the monasteries or holy sites to make merry, take a break from their work in the fields, and proffer their prayers and offerings to God. Each monastery or holy site was thought to have miraculous properties – the healing of illnesses, the healing of the lame and the blind, the granting of wishes, the inducing or facilitation of childbirth, etc [16].

Some of the particularly renowned monasteries of Van (Varakavank, Lim, Gdouts, Khatoun Diramor, etc.) were also destinations for pilgrims. Upon entering a monastery, they would immediately head to the chapel, where they would pray and present their offerings. Wealthy pilgrims would spend the night at the monastery, in rooms specially reserved for pilgrims. Those of more modest means would lodge in nearby villages, or pitch tents under the open sky. While these pilgrimages caused some inconvenience to the monasteries’ monks, they were still welcome, as they were a regular source of income and injected energy into monastic life [17].

Between the 1870s and 1914, monastic life experienced a continuous decline in Van, as it did throughout Ottoman Armenia. This decline was due to two key factors – first, the regular raids on Armenian monasteries by Kurdish bandits. The Ottoman government often ignored these and allowed the perpetrators to go unpunished. Second, the steady secularization of the Armenian population, resulting in a decline in those who chose to join monastic orders.

The monasteries of Van experienced a period of particular devastation during the Hamidian massacres. In 1895-1896, Kurdish marauders destroyed and looted almost all functioning monasteries in Van. In Hayots Tsor, the Sbidag (White) Holy Virgin, the Holy Virgin of Ankgh, Srkhou, Holy Virgin of Ermer, and Saint Kevork monasteries were all attacked [18]. In Timar, the Alid, Holy Echmiadzin of Ererna, and Amkou monasteries were attacked. Other targets included the “outer houses” of Lim and Gdouts (outer houses were structures belonging to the monasteries built on the mainland shores across the respective monasteries’ islands) [19], and the Holy Virgin Monastery in Ardjag [20]. During the massacres of Armenians in Van and the surrounding areas (June 1896), the monasteries of the Van-Dosb cluster of villagers (Varakavank, Garmravor Holy Virgin, Holy Cross, Saint Krikor of Salnabad) were looted and burned. Monks residing in the monasteries, Armenian civilians who had taken refuge in them, and students in adjacent schools were killed [21]. Only the Lim and Gdouts monasteries, impregnable thanks to their positions on islands, avoided the wave of destruction, and in their turn provided refuge for approximately 10,000 Armenian refugees [22].

According to a comprehensive report prepared in 1896, during the Hamidian massacres, in Hayots Tsor, five monasteries were looted and burned, six churches were burned, and 14 clergymen were killed. In Timar, five monasteries were attacked, and two clergymen killed. In Van-Dosb and Ardjag, two churches and four monasteries were attacked, and four clergymen were killed [23].

As a result of these events, in the early years of the 1870s-1910 period, many of the monasteries of Van-Vasbouragan were deserted or abandoned, and fell into ruin. According to one source, in the mid-1870s, Vasbouragan was home to 70 functioning monasteries, with 1,500 monks. By the early 1910s, only 30 monasteries were left standing [24].

Bishop Yeremia Devgants, who visited the Holy Virgin Monastery in the Alur village of Van on official business probably in 1873, half-jokingly remarked in his notes that due to the lack of monks, four cats constituted the monastery’s entire order [25].

By the eve of the Genocide, only few monasteries in Van had stable orders, and even those consisted of only one to three members. The other monasteries functioned only nominally, and were administered by visiting clergymen, priests of neighboring Armenian-populated villages, boards of trustees, and sometimes even by random laypeople who had established habitation within their walls (see the section of the article devoted to individual monasteries).

Once the monasteries were abandoned and left unattended, their vast lands were taken over and put to use by local Armenian and Kurdish villagers in exchange for negligible payments, and sometimes even for free.

Even the larger, functioning monastic orders complained of the high cost of maintenance of monastic buildings and estates, and the poor living conditions that resulted from the lack of funds. To wit, the abbot of the Lim Diocese, Father Magar Der-Hovhannissian, in a letter from 1911, wrote that the Lim Monastery did not have a threshing machine, which meant that a portion of the grain that the monks harvested was left to rot. He also noted that most of the monasteries that were under the jurisdiction of the diocese (Echmiadzin, Saint Hagop) were already mostly in ruins [26].

The urgent need to overcome the destruction wreaked by Kurdish raids and improve the deplorable financial condition of these monasteries prompted the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate to agree to place some monasteries under the directorship of boards of trustees consisting of laypeople. Such a board of trustees was established to administer Varakavank after the Hamidian massacres (for details, see the section of the article devoted to Varakavank).

The administration of a monastery was also placed in the hands of laypeople or secular boards if, for one reason or another (deaths or massacres), the monastery ceased functioning and no longer had serving monks, or if none of its monks, due to old age, were able to fulfill the responsibilities of an abbot [27].

The Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate and local provincial councils developed plans to transform defunct monasteries that still had standing buildings into educational establishments. Boarding schools were opened in many of Van’s monasteries (Varakavank, Saint Kevork of Salnabad, Garmravor Holy Virgin). These boarding schools were established to serve children who had become orphaned during the 1894-1896 Hamidian massacres. Funding came from many sources, including a portion of the rents paid by locals for the use of the monasteries’ lands [28]. Schools and boarding schools operated in many of these monasteries, with some interruptions, until the Genocide.

After the Young Turk Revolution, local Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) institutions also made a positive contribution to the efficient administration of the finances of Van’s monasteries. For example, in Hayots Tsor, ARF activists had some success in improving the administration of the monasteries’ lands. Their efforts led to an increase in income obtained from land leases, and they used this extra income to fund the local Armenian schools [29].

Thanks to the active interventions of national institutions after the Young Turk Revolution, at least the financial situation of Van’s monasteries showed signs of improvement. Gradually, energy returned to monastic life, as evidenced by the increase in the number of monks in certain large monasteries. But the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and the Armenian Genocide brought this process to an end.

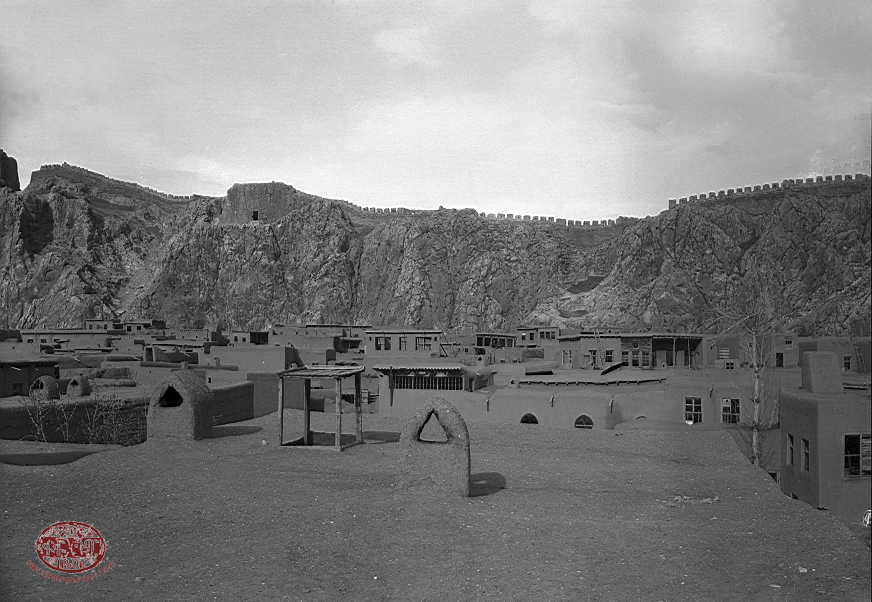

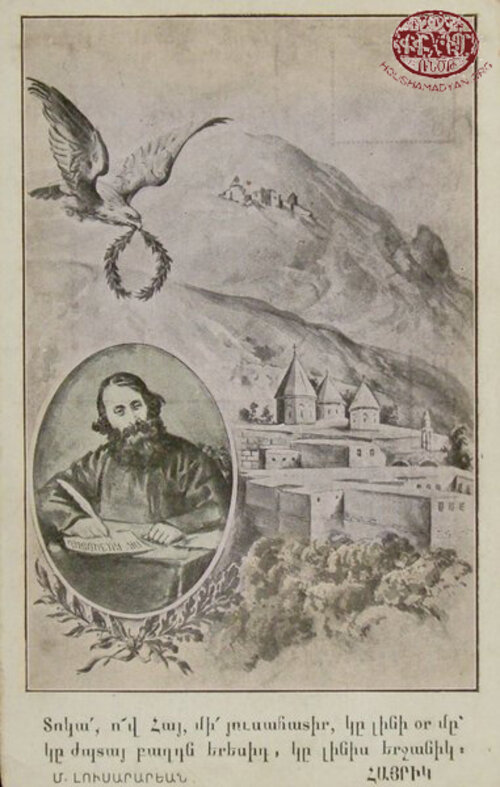

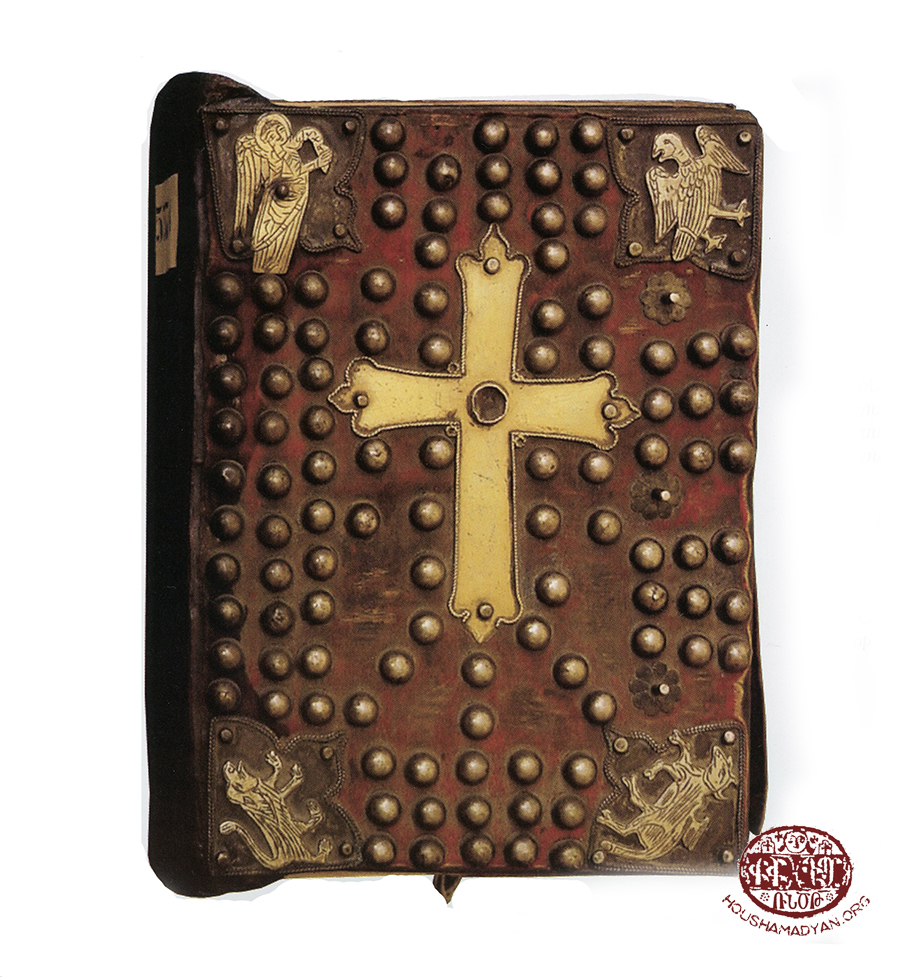

The monastery of Varak in Van (Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice. Courtesy of Father Vahan Ohanian)

The religious life of Van Armenians (mid-1870s-1914)

Prior to the Armenian Genocide, almost every single Armenian community in Van had one or more functioning churches. These churches were generally identical in appearance, built of stone and mud bricks. Churches built or rebuilt in later years were noted for their large size, simple aesthetics, and their well-illuminated interiors [30].

The skeletons of churches built in later years consisted of a dense network of logs, on top of which the builders arranged the purlins and laid down a layer of reeds. The structure was then covered with soil, and reinforced and plastered with a mixture of clay and hay. Many of the churches had spires, which, as a rule, were made of wood or planks of wood. Such churches were described as paydaharg or paydashen in records, meaning they had wooden roofs or ceilings.

The interiors of the churches were painted with a white coating. The floors were of wood, covered with straw mats and rugs [31].

Past the entrance, each church had cabinets on the right and left sides, where worshippers stored their shoes upon entering (to enter a church shod was considered inappropriate in Van) [32].

Almost all the churches of the City of Van and the rest of the sub-district had upper decks consisting of one or two floors, reserved for women [33]. For example, in Ardjag, the women’s section was separated from the rest of the church by iron bars that began right at the entrance. The women’s section had two floors – the young girls and the brides sat above, and below them sat the older women [34].

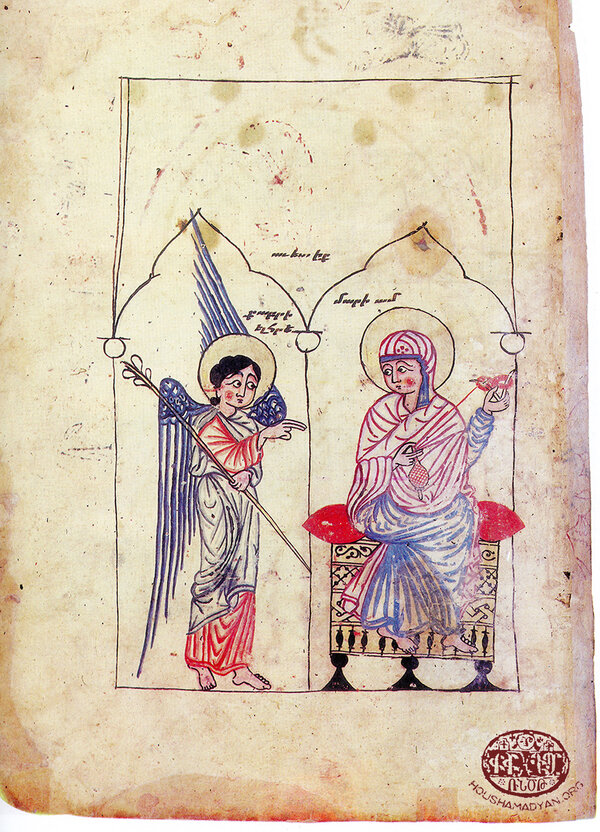

The altars in these churches [35] were covered with a sheet and adorned with an image of the Holy Virgin, and in front of it, in order of size, were arranged candelabras, bibles, vases, etc. Icons were hung from the walls. Light came from small and large torches, lamps, and candelabras. The torches and lamps were hung from the ceiling with cord, while the candelabras were placed on the altars or affixed near the icons [36].

To invite the people to Divine Liturgy, churches used bells and wooden clappers. The clappers were used to signal that the time of the service was near, and it began immediately after the pealing of the bells. Every morning, both in the summer and winter, all the sextons of the City of Van, one or two hours before the start of service, would take up their special wooden clappers and would make the rounds of the parish as they sang hymns. They would stop at every door and beat the door knockers. This tradition was almost unique, and aside from Van, was practiced in only a few Armenian-populated settlements of the Ottoman Empire [37].

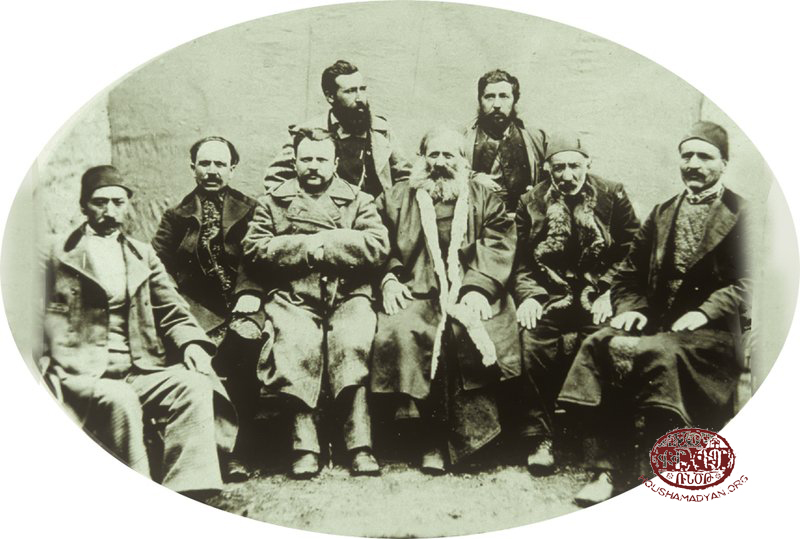

Van, December 1879: Khrimian and local Armenian notables. Seated (from left): Karapet Isajanian, Mkrtitch Marutian, Kerovbe Guyumchian, Father Mkrtitch Khrimian, Gevorg bey Galdjian, Harutyun Terzibashian. Standing (from left): Sedrak Tevkants, Father Garegin Servandztiants (Source: Michel Paboudjian collection, Paris)

All churches of the Aykesdan neighborhood of Van would hold services every morning and every night, without exception, and would celebrate Divine Liturgy on Saturdays and Sundays. This was also the case with the churches in central Van until the late 19th century. But due to the yearly decrease in the number of churchgoers, and by consequence, the dwindling of the churches’ income, a decision was made in 1899 to hold daily services in only one church in the city, with each church taking a one-month turn [38].

The churches of Van were not wealthy. Their assets consisted of the properties that had been endowed to them over the years by philanthropists (homes, shops, farmland, windmills, olive oil presses, vineyards, etc.) and the donations that parishioners slipped into the collection boxes [39].

The income of churches was used to maintain neighborhood parochial schools and to meet the churches’ own financial needs. Immediate oversight over the churches was entrusted to neighborhood councils. As for the administration of the church’s internal affairs, this was entrusted to a yeretspokhi or yerespokhin (deputy) elected by each neighborhood council. These deputies served indefinite terms, and were usually individuals who enjoyed some prominence within their neighborhoods. Once a year, the deputy would present his accounts to the neighborhood council [40].

The institution of deputies also existed in other large settlements of the Van Sub-district. For example, in Ardjag, the deputy was responsible for both the oversight of church affairs and for the proper operation of affiliated parochial schools. Specifically, the deputy was responsible for fitting the school’s doors with locks, installing glass in the windows, procuring heaters and fuel, plastering the church’s and school’s roofs, providing schoolteachers with housing, ensuring the proper operation of the church’s olive oil press, using any income generated by these activities for worthwhile purposes, etc. [41].

The deputy’s home was open to any and all who traveled on church business, specifically pilgrims who came to Van from elsewhere and the elderly or destitute who possessed church decrees to collect alms, and who were otherwise serious and respectable people. They were accompanied by the deputy as they went door to door and as they sold the grain they collected [42].

At the start of the 20th century, each of the churches in the City of Van had one to four serving priests. A large proportion of these priests, both before their ordination into the priesthood, as well as while serving in that capacity, also served as teachers in the churches’ parochial schools [43].

A nielloed silver tobacco box manufactured in Van. The depiction features Mother Armenia weeping over her ruins on the left, and the Varaka Monastery on the right. Kept in a personal collection. 9.5 x 7.5 x 1.5 centimeters, 119 grams (Source: Osep Tokat, Armenian Master Silversmiths, Tigran Mets Printing House, Yerevan, 2005)

The sources of income of individual priests were the fees they charged for baptisms, weddings, funerals, water-consecration ceremonies, house-blessing ceremonies during Easter, grave-blessing ceremonies, as well as incidental and indirect gifts [44].

Armenian ethnographer Serine Avakian, a native of Ardjag, provides a description of house-blessing ceremonies performed in the Ardjag area. We can presume that the ceremony was performed in generally the same fashion in other parts of the Van Sub-district. During the Christmas holidays, the priest would make the rounds of his parish alongside the sexton and two choir boys. The women would place two loaves of lavash bread on a flour sifter. The priest would bless the home and the flour sifter, and the sexton would take the bread and put it in his cloth sack. Then the priest would place a circular eucharist engraved with the image of Christ on the sifter. The lady of the blessed home would then kiss the cross and Bible held by the priest, and while kissing the Bible, would place the requisite fee for the ceremony, the dnokhnela, on top of it. The payment would usually consist of a silver 40-para coin or a two-kurus coin. No exact fee was ever established for the house-blessing ceremony. The same ceremony was performed on Easter, with the difference that on that occasion, in addition to the two loaves of bread, the offerings would also include four red eggs, gifts for the young choir boys [45].

For weddings, baptisms, and funerals, the customary priest’s fee in Ardjag was five kurus, and payment was not required in advance. In cases where the family could not afford the fee, the priest would still willingly fulfill his spiritual duties. Priests were the most important attendees of engagement and wedding ceremonies, and as such were the first to be invited [46].

Aside from house-blessing and grave-blessing ceremonies and other insignificant sources of personal income, clergymen also collected all income generated by their churches, then divided it equally among themselves [47].

It was customary in the Van Sub-District for towns and villages to make one-time yearly gifts to local priests. As such, each year, each parish in Ardjag gifted its priest one okha (1.28 kilograms) of oil, and made one worker available to work in the priest’s fields [48].

One of the positions available in Van’s churches was that of the lousarar (lamplighter), responsible for the “lamps and lights” of the church. In the mornings and evenings, he was the one who lit the church’s lamps before services. He was tasked with purchasing the candles and incense used during services, as well as the wine that was to be blessed. Alongside the priest, the lousarar would prepare the bantsrats (leaven bread), thin as cigarette paper, and the eucharists stamped with the image of the crucifixion. During services, the lousarar would distribute the bantsrats to the parishioners. He would also ensure the proper preservation of the church’s Bibles and other holy items, and would keep the church’s ecclesiastical attire clean [49].

The sexton’s duties were to ring the bells twice a day – at dawn and at dusk. He would also fill the lamps with oil, replace the used wicks, clean the snow from the church’s roof, sweep the floor, etc. [50].

When the Divine Liturgy was celebrated in the church, the sexton was the first to arrive and the last to leave. He was entrusted with the church’s keys. In the case of a death in the village, the sexton was the first to knock on the bereaved home’s door. If the deceased were a man, he was one of those who cleaned the corpse, and when it came time to carry the corpse to church, he was the first of the pallbearers. Once the corpse was back at church, he was also the one who dressed it. Alongside and on an equal footing with the deceased’s loved ones, he would carry him on his own shoulders, all the way to the grave [51].

In Ardjag, the sexton’s pay consisted of the following – at harvest time, each wealthy home would provide him with four rpeks of wheat; and once a year, each household would provide him with seven holiday loaves of bread (which the housewives would bring to church themselves, praying along the way). He also received two loaves of bread from each household he visited on house-blessing ceremonies during the holidays [52].

The church choristers who served in the larger settlements of Van Sub-district were usually literate youth endowed with a good voice, and who served in this capacity voluntarily, many of them motivated by their love of music. Sometimes, during holiday services, the senior choristers of the churches, swinging the perfumed censer in one hand, and the collection bowl in the other, would approach the worshippers, and would whisper to them – “for incense and candles,” “for Haysmavourks,” “for the parsonage,” etc. The worshippers would slip ten or twenty paras in the collection bowl, thus participating in the churches’ fundraising efforts [53].

In Van’s churches, the choir boys were students in the higher grades of local schools who had good singing voices. These 14/15-year-old teenagers, dressed in church robes, participated in the singing of hymns; swung the censers; read biblical passages inscribed on long and narrow strips of paper; helped the priests during the ceremony of the eucharist; made the rounds of homes alongside priests on house-blessing ceremonies and performed the requisite chants and hymns; stood behind the priests holding candles during wedding ceremonies; and after wedding ceremonies, joined the choirs that led the newly-wed bride and groom out of the church [54].

The people of Van were pious. On Sundays and religious holidays, the churches brimmed with masses of people. In the City of Van, those who encountered churches on their morning commutes had a habit of entering them, kneeling and crossing themselves, and only then resuming their journeys to work [55].

The people spared no efforts to improve the financial standing of their churches. During the 1896 massacres of Van, alongside residences and other structures, three of Aykesdan’s five churches were burned. In a short period of time, the people raised the necessary funds and organized efforts to rebuild these churches. “All three churches were rebuilt, thanks to the money piously donated by the people. All three were sturdier and more beautiful than they had been before the fires,” recorded one contemporary [56].

Based on the information we’ve gleaned from our sources, we can conclude that as of the eve of the Armenian Genocide, almost all churches operating in the Armenian-populated settlements of the Van Sub-district had been renovated and were in good repair. Each of these churches had at least one, or in the cases of larger cities or towns, more than one serving clergymen.

[1] Dzeroug, “Vani Nahanke Nergayoums” [“The Province of Van Today”], III, Mourdj, Tbilisi, 1904, No. 3, pages 42-43; and Маевскiй, В. Т., Военно-Статистическое описанiе Ванскаго и Битлисскаго вилаетовъ, I. Географическiй очеркъ, Тифлисъ, Типографiя Штаба Кавк. воен. окр., 1904, pages 10-11.

[2] A-To, Medz Tebker Vasbouraganoum 1914-1915Tvagannerin [Significant Events in Vasbouragan, Years 1914-1915], Yerevan, Louys Printing House, 1917, pages 11-13, 18 and 21.

[3] M. Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin yev ir Badmoutyune,Vartabedoutyune, Varchoutyune, Paregarkoutyune, Araroghoutyune, Kraganoutyune, ou Nerga Gatsoutyune [The Armenian Church and its History, Priesthood, Administration, Reforms, Rituals, Literature, and Current State], Constantinople, 1911, pages 261 and 265; and Arshag Alnoyadjian, “Arachnortagan Vidjagner” [Jurisdictions of Prelacies], 1908 Entartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1908 Comprehensive Calendar of the Saint Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1908, pages 312-313 and 346. For information on the administrative status of Hayots Tsor, see Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and its Flock's Catastrophic Year of 1915], New York, 1985, page 37; and S. Garabedian, Hayasadni Badmoutyun, Hador A – Hayots Tsor [History of Armenia, Volume A – Hayots Tsor], Yerevan, Research on Armenian Architecture Foundation, 2015, page 32.

[4] Alboyadjian, “Aratchnortagan Vidjagner”, page 312.

[5] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 40.

[6] Alboyadjian, “Aratchnortagan Vidjagner”, page 313.

[7] Ibid.

[8] N. Aginian, Kavazanakirk Gatoghigosats Aghtamara: Badmagan Ousoumnasiroutyun [Book of Catholicoses of Aghtamar: A Historical Study], Vienna, Mekhitarine Printing Press, 1920, page 192; and Alboyadjian, “Aratchnortagan Vidjagner”, page 345.

[9] 1904 Entartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1904 Comprehensive Calendar of the Saint Savior Armenian Hospital, Constantinople, H. Madteosian Printing Press, 1904, pages 371-372 and 394-395.

[10] G. B. Adanalian, Houshartsan Hay Avedaranaganats yev Avedaranagan Yegeghetsvo (Knnagan Dzanotoutyunnerov) [Tribute to Armenian Protestants and the Armenian Protestant Church (with Critical Notes)], Fresno, 1952, page 471; and Dzeroug, Vani Nahanke Nergayoums, XXV, Mourdj, 1904, N. 12, page 59.

[11] When the First World War broke out, Reverend George Reynolds was in the United States, raising funds for the Protestant schools of Van. In his absence, his duties were delegated to Mrs. Reynolds (see The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-16. Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Falloden by Viscount Bryce, London, 1916, page 33).

[12] Adanalian, Houshartsan…, pages 472-474.

[13] Grace H. Knapp, The Mission at Van in Turkey in War Time, privately printed, 1916, pages 11-12.

[14] Survey of the Work of the American Board in Turkey. Reprinted of the “Orient” of July 6, 1910, Bible House, Constantinople, Turkey, page 12; and Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin…, page 261.

[15] H. Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere [The Monasteries of Vasbouragan-Van], Part C., Vienna, Mekhitarine Press, 1940, page 976.

[16] Ashkhadank Literary, Political, and Economic Weekly, Van, March 20, 1911, N. 10, page 4.

[17] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part C., page 1101.

[18] Ararad, Holy Echmiadzin, 1896, E., May, page 247 (“Aghtamara Hankoutsyal Khachadour Gatoghigosi Verchin Toughtn yev Deghegakire”).

[19] Ararad, Holy Echmiadzin, 1896, B., February, page 89 (“Hayasdanyats Yegeghetsin Dadjgasdanoum”).

[20] Ashkhadank Weekly, Van, May 29, 1911, N. 18, page 12.

[21] Ararad, Holy Echmiadzin, 1896, L., December, page 579 (“Deghegakir Vasbouragani Godoradzin”).

[22] Puzantyon, Constantinople, February 21 (March 6) 1911, N. 4366 (Father Magar Der-Hovhannesian, “Vana Dzovn yev ir Gghzinere”).

[23] Ararad, Holy Echmiadzin, 1896, L., December, page 586 (“Deghegakir Vasbouragani Godoradzin”).

[24] Ashkhadank Weekly, Van, March 20, 1911, N. 10, page 4.

[25] Y. Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun Partsr Hayk yev Vasbouragan1872-1873 [Travels in Upper Hayk and Vasbouragan 1872-1873], Yerevan, History Institute of the Academy of Science of Armenia, 1991, page 266.

[26] Puzantyon, Constantinople, February 23 (March 8) 1911, N. 4368 (Father Magar Der-Hovhannesian, “Vana Dzovn yev ir Gghzinere”).

[27] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part C., page 995.

[28] Ibid., page 1089.

[29] Ahskhadank Weekly, Van, March 20, 1911, N. 10, page 5.

[30] Dzeroug, “Vani Nahanke Nergayoums”, XXIV, Mourdj, 1904, N. 12, page 40.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid., page 41.

[33] Ibid.

[34] S. M. Avakian, Ardjag, Yerevan, Science Academy of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic – Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography, 1978, page 57.

[35] The altar is the table-like platform used by priests during the celebration of Divine Liturgy.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Dzeroug, “Vani Nahanke Nergayoums”, page 31.

[38] Ibid., page 42.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid., page 43.

[41] Avakian, Ardjag, page 57.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Dzeroug, “Vani Nahanke Nergayoums”, page 44.

[44] Ibid., page 46.

[45] Avakian, Ardjag, page 56.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Dzeroug, “Vani Nahanke Nergayoums”, page 46.

[48] Avakian, Ardjag, page 55.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid., page 56.

[55] Dzeroug, “Vani Nahanke Nergayoums”, page 49.

[56] Ibid.