Marash - Schools

Author: Varty Keshishian, 15 Feb. 2012 (Last modified 15 Feb. 2012) Translator: Ara Stepan Melkonian

The beginning

The organisation of educational work in the modern sense among the Armenians of Marash begins in the middle of the 19th century. Until that time educational enterprises have been generally of an individual and accidental nature.

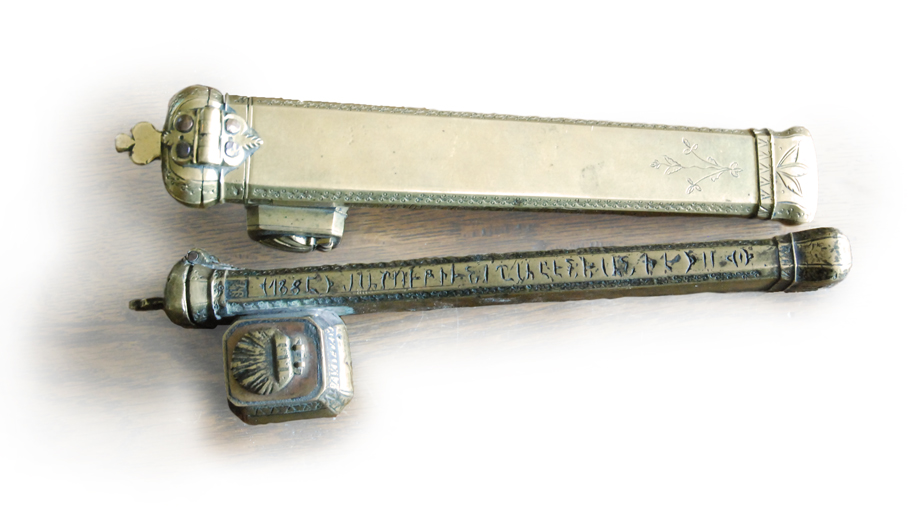

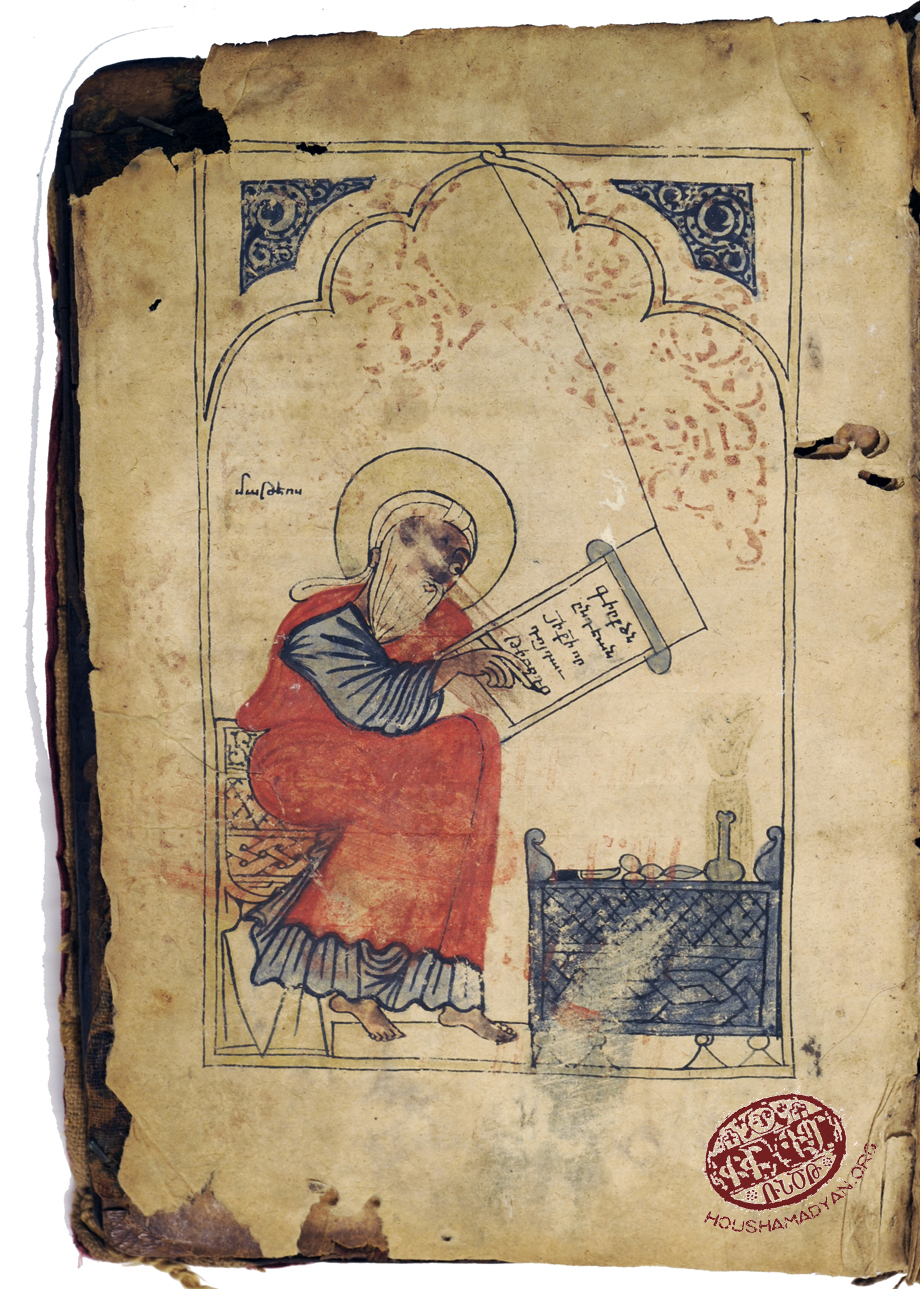

It is known from history however, that in the Middle Ages monastic schools had been established in Marash with the contemporary understanding that they were centres of spiritual culture and education. One of the Marash historians, Harutiun Nashalian, writes about this: ‘It is a traditional story that that in the olden days the monasteries of St Toros and St Hagop were educational centres in Marash.’ According to Nashalian, the places on the hills to the west of the town where the former monasteries were situated are pilgrimage sites for the people: St Toros with its one tree, and the place St Hagop was located, called ‘Tekke’, in other words ‘monastery’. It is said that the St Hagop monastery, built on the height of the Armenian Quarter (Tekke mahallesi), has been especially well known for its order of monks. [1] According to the understanding of the time, this high quality centre of learning taught, after the alphabet, the Psalms, Nareg and Gospel, church singing and ‘the copying of rare and difficult-to-find works with a reed pen on vellum and decorating them with beautiful miniature paintings.’ [2] The colophons in Armenian manuscripts and other related sources testify that Armenian manuscripts have been written and copied in the monastic centres of Marash and Zeytun throughout the Middle Ages. These monastic schools have had distinct traditions that continued those of the centres of learning in Armenia, succeeding in keeping the lantern of learning and enlightenment burning.

In his recollections of the St Kevork Primary School (dzaghgots), the conscientious Armenian historian Krikor Kalusdian relates that St Kevork church kept ancient Armenian manuscripts and church vessels that belonged to the St Hagop monastery. He writes: ‘A few years before the 1895 massacres, when I attended St Kevork Primary School, I often thumbed through the great vellum volumes that had leather-covered wooden covers, and were strongly bound, that were piled up in the dark and damp cupboards in the ‘cabin’ opposite the school: examples of the ‘Book of Days’, breviary, and other church manuscripts... It was said that these manuscripts as well as some of the vessels had been brought from the ‘Tekke’ (St Hagop) monastery.’ [3]

According to the authors who have recorded the history of the Marash Armenians, at the beginning, when there still weren’t any primary or other schools attached to the churches, the monks of the above-mentioned order would teach their apprentices how to read and write using boards (takhta) in their places of work, be they at pit looms or workshops. A takhta was a square board hung from the apprentice’s neck by a string, on which the alphabet was written. After absorbing the alphabet, the apprentice would be given the actual Book of Psalms from the Old Testament. This would be followed by the Bible, with the rest of its books, Nareg, the book of canticles etc. The choristers who attended church would learn canticles and church chants by rote. [4]

This is one of the testimonies that establishes the fact that the Armenians of Marash have not been indifferent towards education and learning, and have tried, as far as possible, to pass down their mother tongue along with religious knowledge.

Among the educated churchmen, the monk Archpriest Khachadur Der-Ghazarian, describing the educational life at the beginning of the 19th century says that at the beginning, due to the absence of schools, the children would attend the married priests’ (kahana) homes, squatting next to the pit looms, where they would learn the Psalms, Nareg and would spell out grammar. He added ’20-30 sons of the great aghas attended my father’s (Rev Ghazar’s) house.’ [5]

As noted above, until the middle of the 19th century the new generation’s knowledge of writing, grammar and certain religious things have been brought about in the workplace or in the monks’ cells in the churches under poor conditions using a takhta. Truth demands, however, that it should be said that it was the generation that grew up being taught using this method and under those conditions that eased the path for the Marash Armenian education and enlightenment movement in the new era.

The first new kind of educational establishment has been opened in 1828-30 in St Kevork church, by one of the notables, Kevork Agha Topalian [6] and is of particular interest. A descendant of the wealthy, famous Topalian family, Kevork Agha had an influential position not only among the Armenian public, but also that of the Turks. The first regular school in Marash for local boys was opened through his means and personal initiative.

It is said that in 1824 a young man by the name of Stepan Karayapudjian, after receiving his basic education of the Psalms and Nareg in Marash, has gone to the St Garabed monastery in Kayseri to complete it. Upon his return, he has been ordained a married priest of the St Sarkis diocese [7] as the 35th to take holy orders in his family. This educated new priest has been invited by Kevork Agha Topalian to be a teacher in his newly-opened school.

According to a second testimony, Kevork Topalian has had a house built and, having invited a teacher named Garabed from Kayseri to Marash, has opened a new school in the new building, having collected a significant number of boys and provided them with an education.

It can be seen that the two descriptions concerning the first school are very similar, with only the teachers being different; it is not explained whether these two people taught at the same or different times.

Archpriest Rev Khachadur Der-Ghazarian provides information of equal importance about this: ‘A regular school has been opened for the first time in Marash in St Kevork church, thanks to the efforts and generosity of the well-respected Topalian family. The teacher is Garabed from Kayseri, named gözlüklü (spectacles wearer), who teaches the four subjects, namely grammar, logic, oratory and mathematics.’ [8]

As the first school, it has also taken on the role of being the first in the organisation of education among the Armenians of Marash. This diocesan school has provided the Marash Armenians with educated clergymen and lay activists, who have later become the organisers of church, educational and public life in Marash in the new era. The former students of this educational establishment are Catholicos Mgerdich Kefsizian; Archpriest Nahabed Der-Garabedian; the diocesan priest of the parish of The Forty Innocents Rev Mgerdich and the notable in the same parish Vartan Topalian; Rev Garabed Saatdjian, Rev Mesrob Dishchekenian, Rev Garabed Aghayian (Agho irets) and Rev Bedros Mevchugian from St Kevork diocese; and the teacher Khacher (khalfa) Der-Mesrobian and others from St Stepannos diocese. [9]

The boys who enter the school, first begin with the alphabet, in other words with letter recognition, then they are taught the Psalms, Nareg, the Acts of the Apostles as well as mathematics. It is only after they have assimilated these that they begin to take up Father Mikayel Chamichian’s large book of grammar. It is said that Kevork Agha Topalian, even before the school opened, when he has gone to Istanbul on business, has returned to Marash with many useful books printed by the Mekhitarians of Venice.

In a short time the school has begun to work well, but Kevork Agha Topalian has been killed as he was crossing the bridge over the Djihan River, three hours away from Marash, due to a misunderstanding. As he is no longer the school’s patron, it has qucikly closed.

An educated monk from Echmiadzin named Archpriest Serovpe has came to Marash in the 1840s and taught in the same St Kevork school for 5 or 6 years, giving lessons in classical Armenian composition, grammar, oratory, logic, mathematics, geography and other subjects. It is said that to make geography lessons more easily understandable, he draws maps on large melons and uses them as teaching aids. Students who have improved their education under Rev Serovpe are Archpriest Nahabed Der-Garabedian, Archpriest Hovhannes Varjabedian, the notable Vartavar Kuyumdjian and others. [10]

So it is through the generation that more or less obtained its education in these schools and with its immediate participation that, from the 1840s, primary schools known as dzaghgots have begun to open in the six churches of Marash. It is in this sense that it is important to appreciate or value all the personal efforts that, in their turn, have an important role in the organisation of the education of the new generation of Marash Armenians.

* * * *

Before presenting individual pages from Marash’s educational life, I think it is imperative to first deal with a number of factors that has enabled its progress.

From the middle of the 19th century, the reforms begun in the Ottoman Empire through the Tanzimat on the one hand and, on the other, the education-enlightenment wave that has spread through the Armenian provinces with the Armenian National Constitution has breathed new life into Marash Armenian public educational life.

Several pro-education associations have appeared on the scene whose main aims are the opening of schools and boosting educational efforts. These bodies, gathered around dioceses, churches and schools, have been created to assist the schools in their dioceses, to secure the educational needs of the children. They are: for St Stepannos diocese – Rupinian; The Holy Mother of God – Mamigonian; St Kevork – Lusinian; The Forty Innocents church – Haiuhyats (Armenian Women’s); the Central School – Giligian Hayrenasirats (Cilician Patriotic) and others. [11]

Of course, during this era of the general blossoming of education and enlightenment, a great role has been reserved for Istanbul, where even from the first half of the 19th century a new and powerful educational movement that has begun to gradually spread into various provincial centres.

As in many centres, in Marash too, the basic forces that drive the educational awakening are the two mutually supporting important forces – the progressive clergy and the representatives of the class of wealthy merchants, the first with its intellectual abilities, and the second with its financial gifts – that have become the organisers of the educational efforts in the new era.

It cannot be denied that foreign missionary organisations and individual missionaries have assisted in Marash’s educational progress. After entering Marash, the missionaries of the American Mission Board especially have begun to found modern schools, high schools and colleges, enjoying the assistance of the local Armenian Protestant communities. The new methods of education they have imported being the best examples, have become the spur driving the improvement of the Armenian Apostolic community’s schools.

A part of educational life in Marash and among the Marash Armenians has been, after the 1895-96 massacres, the American, British and German missionary organisations’ enlarged activities in the form of the care of orphans. Special mention must be made of the organisation of education in the orphanages-schools that these organisations have opened for thousands of Armenian orphans.

The dzaghgots-primary schools

From the 1850s the six Armenian churches in Marash [12] have opened primary schools known as dzaghgots that are provided for from the church’s income and are subject to the parish council. Later trustee bodies have begun to be organised, reforms in education have been adopted, and these schools have taken on a regular nature.

Unfortunately no information about the foundation and beginning of these basic schools has been preserved; the various authors who have penned memorial books about Marash only give general descriptions of them. Obviously there must have been only a very few records available to Krikor Kalusdian, who has written the history of the Armenians of Marash, concerning educational life of the town, therefore he has composed the chapter on education mainly on the basis of what other authors have written, and on his own recollections.

Several authors provide interesting details about the early days of school life, especially about methods of teaching, order and discipline and customs in the schools that should be quoted here, as there is no other information available.

It is known that the dzaghgots-primary schools attached to the churches used the same plan and almost the same layout. Krikor Kalusdian, describing the St Kevork primary school, attempts to give a general idea of all of them: ‘The primary school attached to St Kevork church is located on the second floor of a long, wooden building near the Shekerdere Valley. It consists of a hall with windows on all four sides without shutters or any panes of glass in them. In winter, to keep out the cold, they are closed with cloth or pieces of wood. Teaching is very far from being regular: the boys are divided into classes according to the books they are reading, and children of different ages are taught together. There are no desks or chairs. The boys sit cross-legged (daghdash) on mats on the floor. Some have brought their own pillows (minder) to recline on. At first the children of wealthy families have their own earthenware braziers (keozliuk). More recently it has become the custom to use metal stoves (soba) with the boys bringing firewood from their homes.’ [13]

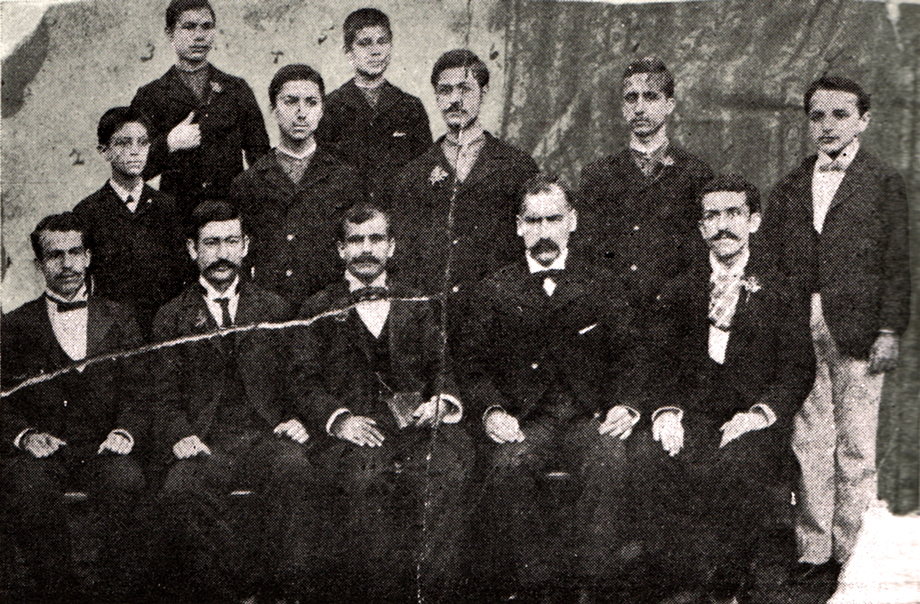

1) Levon Ashdjian (teacher, Marash Academy)

2) Sarkis Samuelian (teacher, Central School)

3) Senior pastor Yeghia Kasuni (teacher, Central School)

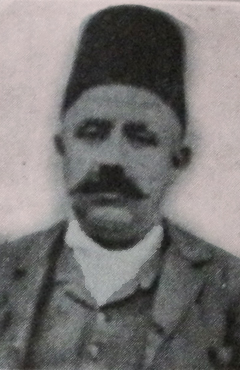

4) Senior pastor Aharon Shiradjian, one of the most important people in Marash’s Armenian educational life

5) Armenag Haigazian, a graduate of the Marash Theological Gymnasium.

6) Haigazun Keshishian (teacher, Central school)

In the beginning, therefore, the dzaghgots are a form of primitive school. The notable information provided by Garabed Der-Ghazarian (Dr Harutiun Der-Ghazarian’s father) that follows concerns this same period: ‘Generally speaking those who were learning to sing canticles and anthems are called khalfa, (khalfe, khalfo), that at the same time means teacher.’ [14] Priests are ordained from the ranks of the khalfas, who know the basics of reading and writing. First the khalfa accepts boys into his house, charging them so much a week; they pay him in coin and or take him, as a gift, cracked wheat, oil, cheese, coal or firewood. When the khalfa is ordained, the boys attend church where he had a small room acting as a school, which is, at the same time, a weaving workshop.

Of the old-time khalfas, famous ones were Khacher khalfa of St Stepannos church, Sarkis Giukiur of St Sarkis, Toros khalfa of the church of The Forty Innocents, all of who taught generations of boys.

The boys, summer and winter, without any holidays, attend the khalfa. They aren’t divided into groups, and during classes, each has to stand and read his lesson. One reads from the Gospel, the next grammar etc. During lessons the khalfa always had a cane ready in his hand, and when anyone makes a mistake, he receives a stroke across his hands. Kalusdian writes: ‘To bring unruly boys to order, the miscreants are often given a heavy ancient manuscript to hold and forced to stand on one foot as punishment.’ [15]

There were other customs. The following statement by G. Der-Ghazarian is interesting: ‘When a pupil reached the 3rd verse of the 2nd psalm in the Book of Psalms where it was written ‘Cut the bonds that bind me, and throw them off,’ the khalfa tears the pupil’s shirt from top to bottom and accepts gifts from his parents.’ [16]

The khalfa won’t give permission for the boys to leave for a break. There is a board hanging on the door, one side of which had ‘He’s come’ and the other ‘He’s gone’. The boys leaves and enters using it so as not to disturb the khalfa when he is working at his weaving. It is only at lunchtime and in the evening, when they are free to go does he say, ‘Pandekhil, dghak’ (You’re free boys, you can leave the prison.) [17]

Garabed Der-Ghazarian’s memories are especially interesting: ‘In my day, the highest form of learning was considered to be knowledge of grammar. Famous among those who knew the subject were Rev Hovhannes Varjabedian, Rev Yeprem Aghazarian and Sarkis Bilezigdjian (later the Protestant pastor Rev Sarkis). Lessons in grammar were taught on a chanting question and answer basis. One of the boys would ask the question and the rest would chant the answer. When a pupil asked, ‘What is grammar?’ all the rest would answer in unison, ‘A skill [teaching you] how to speak correctly and write without mistakes.’ ‘What is a letter? ‘A [written] letter is a form of line, the symbol of the letter [of the alphabet]; the letter itself is the sound that can be spelled.’ ‘What is a syllable?’ ‘A syllable is a part of a word that can be said on its own, made up of letters [of the alphabet],’ and so on. Thus they learned grammar – it needed 4-5 years! This is the schooling that the first educated generation had in Marash.’ [18]

According to Krikor Kalusdian’s testimony, the use of text books in modern Armenian had only just begun when he was in school. After grammar, the boys were given the Small then the Large Book of Psalms, the 1st and 2nd year of the Mother Tongue (Armenian language) text books, a condensed book of Armenian history and one on Christianity. Later they would be given a basic Classical Armenian grammar primer, be taught to read and translate the Gospels (from Classical to Modern Armenian), as well as an Ottoman grammar, a small basic (Ottoman) composition manual, basic arithmetic, geography and so forth. Music lessons completed the syllabus, consisted of singing certain church and patriotic songs. [19]

Kalusdian tells us: ‘The khalfo reclines on a slightly raised platform called a sedir, while we, the boys being taught, kneel in rows one behind the other in front of him, to read the lesson aloud, with almost all of us reading the same page. The khalfo quite often converses with a visitor for hours on end, smoking cigarettes, while we read the lessons. During the heat of summer, the khalfo sometimes falls asleep where he sits, and we continue our reading, while also getting up to mischief.’ [20]

School discipline is maintained in a strange way. The khalfo or his assistant not only gives the lessons, but also supervises the boys, sometimes appointing one or two of the oldest as monitors in their own right. The use of a flakha (thick stick, falaka), beating and punishment are common in schools. The teacher had complete freedom to beat or inflict punishment, because when the parents send their children to school, they say to the teacher, ‘Mase kiz, iuskiuriu yes’ (the flesh to you, the bone to me). Sometimes the beating is unjustified, but the teacher is always considered to be in the right. [21] Despite all this, as the Protestant pastor Rev Harutiun Djenanian testifies: ‘Although some can abscond from school to escape punishment, generally, however, everyone loves the school and considers it a privilege to attend, because many can’t.’ [22]

At the beginning, before the use of bells in the schools, the teacher, looking at the sun, allows the boys to break for lunch or releases them (pandekhil) to go home. The lunch break lasts an hour. The well-to-do bringt their lunches with them or it is brought to them by their sisters at lunch time. The poor boys suffer, as they often have nothing to eat. In the evening the boys are sent home under the supervision of their ‘monitors’.

Archpriest Khachadur Der-Ghazarian relates, in his memoirs, that when the six parish schools attached to the churches opened, the very young children didn’t attend them while, especially on Fridays, from fear of young Turkish ruffians (lagod), the number of boys was less. The Turkish boys would attack Armenian children with stones and catapults on Fridays, with even grown up Turks joining in these fights; the Armenian boys were forced to seek refuge in houses near the schools until the Turks dispersed. [23] As we can see, at times even schoolchildren aren’t free from pressure and violence.

Bringing all the evidence together it is possible to say that, apart from a very few small children, who receive special education from priests and, according to the standards of the time, are well educated, Marash Armenian educational life, especially at the beginning, was far from being satisfactory. Lessons are given in the most primitive conditions. Those boys who receive some sort of education owe it to their natural talents and diligence; they improve the knowledge they had gained by going to different places, asking questions and gathering information – in other words by helping themselves.

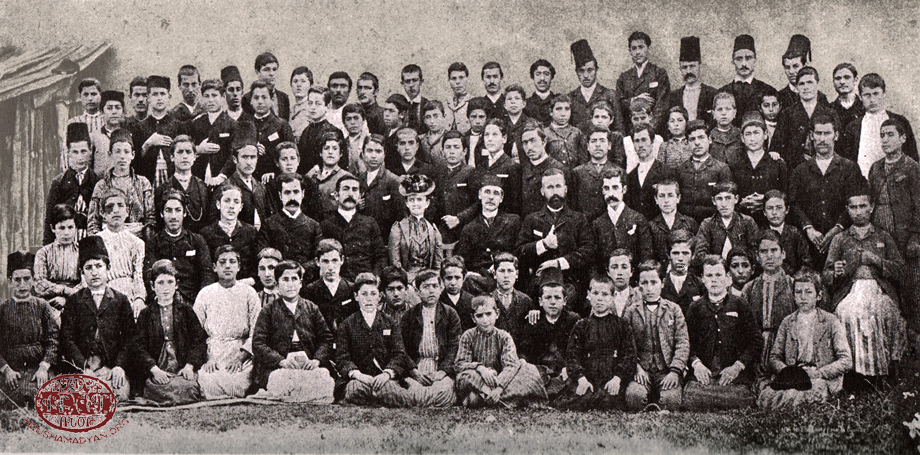

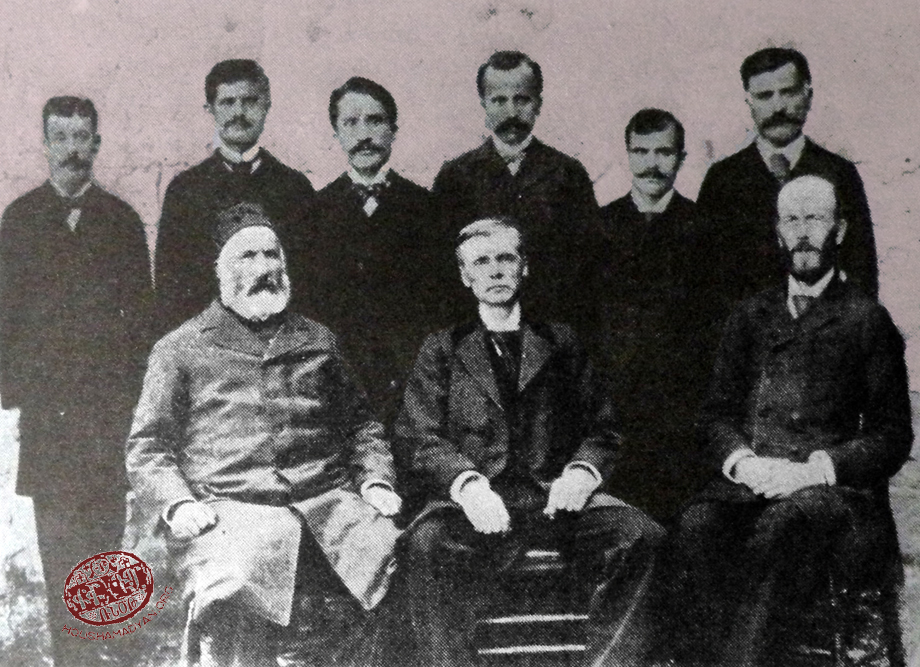

Marash. A group photograph of the students of the Academy High School. Seated, left to right: Sarkis Kiulliugian, Minas Kasardjian, Avedik Poladian, Nshan Zeytuntsian, Vahram Tahmizian. Standing, from left to right: Hagop Bayerian, Levon Giuliuzian, Dikran Yenovkian, Agheksantr Elmadjian, Movses Misiyian, Yervant Elmadjian, Karekin Gharibian (Kalusdian, op. cit.)

* * * *

Due to the Turkish army battles against Zeytun at the beginning of the 1860s, the imperial government in Istanbul has sent a high Armenian official named Sarkis Effendi Aghapegian to Zeytun as an inspector who, to carry out his inspection and write his report has been forced to stay in Marash for a few months. Becoming familiar with the churches and the disorganised state of the Armenian population of Marash, as an educated and knowledgeable Armenian, he has taken the initiative to organise the internal life of the Armenian community of the town in accordance with rules of the National Constitution. Aghapegian has visited the six churches, explained the Constitution to the people, has had copies of it brought from Istanbul and has distributed them among them. Through his efforts and immediate participation, the first parish councils have been set up, and he has tried to reform the pitiful primary schools (dzaghgots – the meaning in actual fact is ‘flower garden’) in Marash which a contemporary has said are more like a khamrots (meaning parched or drying garden). He has also created a plan to make them into proper primary schools.

He has convened a general assembly in The Forty Innocents cathedral, in the presence of the Political Assembly and with the participation of the six parish councils, and has emphasised that, for education to advance, a high school is needed. A decision has been made that the projected school should be opened in St Sarkis church. It has opened quickly, in 1862, and has been given the title of Gymnasium (Djemaran), with Archpriest Hovhannes Varjabedian being appointed its director. [24]

The Gymnasium has continued to teach for six or seven years, with students attending from the notable families of the six churches in Marash, as well as the sons of poor families who needed higher education. The students are taught composition, oratory, logic, geography, mathematics, translation from Classical to Modern Armenian and explanation of the Bible. [25] Among its students have been Rev Garabed Giuliuzian (later locum tenens in Ayntab); Rev Kevork Charkhapanian (Charpanadjian) from St Kevork; Rev Bedros Der-Bedrosian; Rev Mesrob Der-Mesrobian from St Stepannos; bellringer (jamgoch) Harutiun Yepremian (later Rev Yeprem Jamgochian) from St Sarkis diocese; Hampartsum and Hovhannes Topalian; Harutiun, Mardiros and Hovhannes Chorbadjian, Dr Hagopdjan Kalpakian; Yerchanig Rev Ghevont Der-Nahabedian from the Forty Innocents diocese; Harutiun Kuyuymdjian (a lawyer); Harutiun Muradian and others.

The Gymnasium has hardly sown its first seeds when it caught fire in 1864, but thanks to the generosity of the community and the efforts of Rev Hovhannes, it has been rebuilt and continues its syllabus. Some of the most able intellectuals of the time have been numbered among the Gymnasium’s teachers - bellringer (jamgoch) Harutiun Yepremian (later Rev Yeprem Jamgochian, also known as Khadents), whose students are the teachers Sarkis Samuelian, Archpriest Khachadur Der-Ghazarian, Tavit Der-Ghazarian and Soghomon Alixanian, who have played such a significant roles in the intellectual and educational life of Marash. It is said of Rev Yeprem that he has been the first to receive and read newspapers in the town. He is well versed in Classical Armenian, Armenian church music and Turkish. He translates canticles (sharagans) and patriotic songs into Turkish, as well as Bedros Tourian’s ‘If the pale angel of death’ that is sung in Marash. He has composed Turkish songs too, as well as compiling a popular rhyming Armenian-Turkish dictionary in verse. He is also a satirist. [26]

After fertilising the educational life of Marash for six or seven years, the Gymnasium has also passed into history.

Rev Ghevont Der-Nahabedian recalls, in his autobiography, another educational initiative of those years. One of the notable merchants, Deovlet Effendi Chorbadjian, upon his return from a pilgrimage to Jeruslaem in 1874, brought a native of Istanbul, a teacher named Hagop Nazaretian, with him and, with the united efforts of the notables of the six churches, has opened a school in the grounds of St Sarkis church, once more under the directorship of Rev Hovhannes Varjabedian. Nazaretian teaches Armenian language, mathematics, geography and Armenian history, as well as music. Rev Ghevont, as an assistant teacher, teaches Turkish. The school has lasted for two or three years and with the illness and death of Nazaretian, has closed in 1877. [27]

Between 1850 and 1860 the Armenian Catholic and Protestant communities also opened their own special schools.

The teachers and graduates of St Stepannos High School, 1903. Seated, left to right: Garabed Der-Harutiunian, Harutiun Nashalian (teacher), Soghomon Vosgerichian (teacher), Khoren Kutudjian (teacher), Hadji Der-Mesrobian. Standing, first row: Kevork Kapudjian, Stepan Der-Stepanian, Yesayi Harutiunian, Asdour Mikilian, Baruyr Topalian. Standing, second row: Ghevont Kudulian, Armenag Der-Hovhannesian. (Source: Kalusdian, op. cit.)

The Central School (Getronagan Varjaran)

Naturally, the above-mentioned parish schools have not been able to fulfil the needs of the Armenians of Marash, especially the educational demands of the wealthy class. They have started to send their children to receive the necessary education to Ayntab, Istanbul, Tarsus and other centres of education. This is, without doubt, the only way that the new generation can profit from education, but the number who are sent out of Marash are only a very few and can never solve local educational problems. It isn’t surprising that educated, progressive young people, especially those who, for the sake of education, have left to go to the best Armenian educational establishments of the time can’t, when they return, remain indifferent towards educational problems. This is especially true of the heirs of wealthy families that praise education and enlightenment, and not only encourage it, but assist it financially, becoming the people who lay the basis of future Armenian educational progress in Marash.

Thus at the start of the 1880s the much longed-for plan for the foundation of a high school has brought a group of educated and progressive young people from Marash together who, accepting the aim of founding a well-run school, have formed a pro-education association called The Cilician Patriotic Association. The association has taken up the problem of founding a school that will fulfil the requirements of the time and ways of creating a steady income to maintain it. [28] The association has been created through the personal efforts of the locum tenens Archpriest Nahabed Der-Garabedian; its initiators are Hadji Giragos Chorbadjian, Mardiros Chorbadjian, Harutiun Muradian, Garabed Bilezigdjian, Oves Arekian and Mgerdich Hovnanian, [29] all of them representatives of notable Marash Armenian families. The association’s funds have been created through subscriptions, events and collections within the circle of wealthy people.

Generally speaking, the 1880-1890 decade is regarded, alongside the Marash Armenians educational progress, as a period of community awareness. All the contemporary authors completely agree that Marash Armenian community public life is living in a period of intellectual educational reconstruction, ‘there is great enthusiasm in the community and among its leadership to create praiseworthy associations, found lecture halls, give theatrical performances and arrange events.’ [30]

So, in these universally animated conditions, ‘thanks to the efforts and work’ of the Cilician Patriotic Association, Marash’s Central School (Getronagan Varjaran) has been opened in 1880. All the necessary expenses are taken care of by the notables of the town, especially by the well-to-do Armenian merchants and the wealthy trading and production class of Marash. A piece of land in the Shekerli quarter of the town has been purchased for the school thanks to the ‘efforts and concern’ of Boghos Agha Muradian. A Funding committee has been formed to obtain the building costs, under the chairmanship of Mardiros Chorbadjian (of the great Chorbadjian clan). The committee managed to obtain the required sum from the notables of all six churches and the Central School building has been constructed. It has been built quite quickly; there remains the question of teachers. Misak Elmasian (one of the former Shahnazarian School students) has been invited; he is an educated teacher of English and French from Istanbul and he and his family have moved to Marash to take up the position offered. The most promising students of the six parish schools have been chosen to attend and the doors of the famous Central School, the pride of the Armenians of Marash, have been opened in the autumn of 1880. The students come from the different quarters of the town and, it being in the centre, in an airy and good position, has assisted in their attending it.

Elmasian, however, has only stayed for two years and, resigning, has returned with his family to Istanbul.

The Cilician Patriotic Association had set itself the task of preparing and educating young people with clean religious and moral characters, and to awaken interest in, and love of, reading. To this end the first action the association has taken is the founding of a library-museum in the Central School.

This is how K. Kalusdian describes the school in his student days in the 1890s: ‘The Central School building is a large, single storey building. It has a stage and two separate sections, where the student choir and teachers sit during lectures and events. The library, filled with books, called ‘The Museum’, is located behind the stage. It is in this building that the Sunday lectures, events, theatrical performances etc are held. On rainy days it also serves as a playground. At the entry to the courtyard there is a long, two-storey building with two halls and a classroom.’ [31]

In this time of universal enthusiasm for educational enlightenment the spoken word has great influence. The formation of a public lecture system hasn’t been far behind, having as is aim, by means of ‘lectures and sermons’, to spread education and reading among the Marash Armenian community. Judging by the available sources and recollections, the Sunday lectures in the Central School have had a significant role in the progress of Marash Armenian intellectual development. All the authors of histories of Marash, without exception, speak of these lectures with great acclaim, pointing out that it was thanks to them that Marash lives an educational-cultural awakening. [32]

Every Sunday, a great crowd of people listens to sermons and lectures that are given from the Holy Bible, on national and general history, moral philosophy, educational and various other useful subjects. Events and theatrical performances are also held, and patriotic songs also sung.

The Marash diocesan locum tenens, Archpriest Ghevont Nahabedian gives the following valuable information about all this: ‘Every Sunday afternoon we gave sermons, taking turns, to a huge crowd of people. Of the Central School teachers, Sarkis Samuelian and Tavit Der-Ghazarian would speak extemporaneously on religious, moral, educational, scientific and other useful subjects and also read written speeches.’ [33] Der-Nahabedian then adds: ‘The priests and notables from Marash’s six churches come to the lectures, and the school students, after the lectures, sing patriotic songs. A mixed crowd, without gender bias, fills the hall. Those sermons and lectures have been given for many years. Young people occasionally gave performances. This community-benefitting school and the lectures give great service to the Marash Armenian community.’ [34]

These Sunday lectures have promoted great enthusiasm among the people; all the priests of the six churches, the notables as well as the attendance of great crowds of people best testify to the universal enthusiastic atmosphere that has been generated.

It is recalled that every time that Catholicos Mgerdich Kefsezian of the Great House of Cilicia comes to Marash, he visits the Sunday lectures held in the school hall and gives learned sermons there. [35] Generally speaking, at this time, all the clergymen who visit Marash, as well as community-educational activists who come from Istanbul, give lectures in the school hall. Rev Ghevont Der-Nahabedian and his son, Rev Nahabed, as well as Sarkis Samuelian, Smpad Piurad and Tavit Der-Ghazarian, the latter three teachers in the school itself, and certain others too, are all regarded as permanent speakers.

We can find valuable information about Marash’s educational re-awakening and the Central School in Vahan Kiurkdjian’s book ‘National Memoirs’, in which, writing about his visit to Marash in the summer of 1882, he says: ‘Marash at this date is living in a brilliant community-intellectual period of activity – perhaps even surpassing than that of Ayntab. Marash’s Central School is flourishing at this time, under the directorship of Smpad Piurad and Sarkis Samuelian – both selfless and able teachers. There is a great newly-awakened community there that, thanks to being neighbours of Zeytun, is either in crisis or enthusiastic in turn. Deovlet Effendi Chorbadjian is the influential and august patriarch of the Armenian community. Kevork Effendi Muradian (whose son Harutiun Effendi has excited everyone’s envy because he’d received his education in Paris) also carries great weight as a government official – he is a member of the meclisi idare (board of council). General respect has been accorded to Archpriest Nahabed, whose son, the newly-ordained Rev Ghevont is also known as an erudite and bold-speaking priest. It is, finally, a stirring period – four years after the Congress of Berlin. The town has six Apostolic churches, each with its school. The Protestant and Catholic communities also put great efforts into education.’ [36]

Despite the Cilician Patriotic Association’s aim of endowing the school with permanent sources of finance, it never has. The school’s costs are covered by the fees paid by students and the aid given in accordance with a tariff, from the town’s churches.

At the beginning the United Association (Miatzyal engerutiun) of Istanbul has assisted the Marash education effort, either by sending teachers or giving grants, but has since ended them.

During this period, in terms of organising education work, serious steps have been taken by the United Association’s inspector of Cilician schools Krikor Sandaldjian (a graduate of the Paris teaching academy) but he has died suddenly in Marash. According to K. Kalusdian’s evidence, many educational initiatives have remained unfinished that would otherwise have probably been successful through this able inspector’s efforts. He has been succeeded in his position by Parsegh Vartugian who, in October 1882, has visited Marash and introduced new methods into the Marash schools.

The Central School has given the new generation in Marash an Armenian education. From the beginning Armenian subjects have been taught to a suitable standard: Armenian language – both classical and modern, and Armenian history, so that graduates, when they enter American colleges (in the Ottoman Empire) and other higher educational establishments, have no difficulty in keeping up with the standard of Armenian taught in them.

The director-teacher of the Central School in the 1890s is Sarkis Samuelian; among the teachers that are recalled are Hagop Kalemdjian, Hovhannes Kutudjian, Soghomon Vosgerichian, Mihran Ispirian (also known as Khoren Khorkhoruni and who has been one of the students from Catholicos Mgrdich Kefsezian’s school); later Smpad Piurad, Tavit Der-Ghazarian, Turkish expert Toros Mahigian, Rev Ghevont Der-Nahabedian and others. [37]

Sarkis Samuelian is really the leading person among the Central School’s teachers; the Armenians of Marash owe him a great debt for their educational awakening and progress during these years. His tenure of office was a brilliant one for the school. Theatrical performances have been presented, as have been various events. Thanks to his and his fellow-worker Smpad Tavitian’s direct efforts, reading - writing and literature and the Armenian press – have become widespread among Marash’s young people.

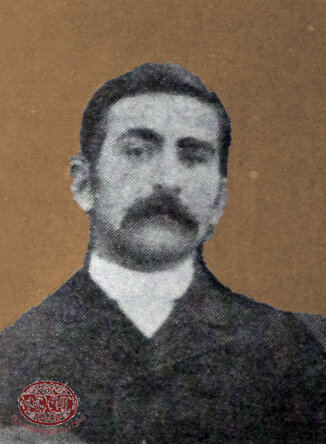

A word about Tavit Der-Ghazarian, who similarly is one of the activists dedicated to the spread of education and enlightenment at the end of the 19th century and has had a significant role in the creation of the intellectual movement. He was born in Marash in 1854, a member of Rev Ghazar’s family. A lover of books and literature from an early age, he had a mentor in his father’s brother Rev Yeprem, who for his time had a large library of books which he opened to Tavit. In 1890, Tavit Der-Ghazarian has attended Ayntab College for two years, then a further two in Marash’s Theological Gymnasium. He has been forced to leave his education for family reasons, but has always stuck to writing and literature and through self-study has become one of Marash’s most erude people. He and his contemporary and close friend Rev Ghevont Der-Nahabedian like to study classical books; according to the testimony of their contemporaries, these two are the most bookish young men in Marash, who greatly assist the development of Marash’s young intellectuals. Rev Ghevont with his eloquent sermons and speeches and Tavit with his writing and teaching have registered a brilliant era in Marash’s literary-educational life in the decade from 1885-1895. At the age of 41 Tavit has fallen victim of the 1895 Armenian massacres. [38]

Smpad Piurad is one of the names that has also left noticeable traces in the history of the Central School, serving as a teacher of Armenian and speaking in the Sunday lecture series.

The school has remained closed for a few years after the 1895 massacres, but has later re-opened, improving from year to year, preparing students for the American colleges in Tarsus and Ayntab and other educational centres.

During the years after the proclamation of the re-establishment of the Ottoman constitution (1908), the Central School has achieved a first-class status. During this period an important change has come about in this establishment’s governing system. This is when the Apostolic and Protestant communities unified their budgets to run the school. The union of the Armenian Apostolic Central School and the Armenian Protestant School has taken place in September 1910, then being called the ‘United Central School’. In this same year the school has received permission from the government to be an 8-year lycee.

During this period the Protestant pastor Rev Garabed Harutiunian has been the director, working with the Protestant pastors Rev Aharon Shiradjian, Rev Yeghia Kasuni (Behesnilian), Professor Elisha Roubian, Apraham Berberian, Siragan Orchanian, Serovpe Basmadjian, Mardiros Terzian, Nshan Yezegielian, Haygazun Keshishian, Hovhannes Torian, Hovsep Vehuni and others as teachers. [39]

This inter-community educational co-operation hasn’t last long, despite the fact that the written agreement has been ratified by the responsible officials on both sides and by the Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia. But as it has turned out, however, from perusal of the various sources, that just as the union has been unprecedented, so is it delicate, and in the end religious doctrinal differences have made the separation inevitable.

In 1910, through the efforts and financial assistance of the prelate of the day, Bishop Mgerdich Vehabedian, as well as collections taken up by the people and their voluntary work, a second storey has been added to the large school building, creating eight new classrooms and a large hall. [40]

The First World War and the deportations supervened and, like all Armenian establishments, the Central School has also been ruined.

After the Armistice, in 1919, the school has re-opened with new energy, this time with the co-operation of the Armenian Apostolic and Armenian Catholic communities. The director’s position has been filled by Professor Aram Baghdigian. The number of students has risen until it has reached 400. The school’s budget, which was 100 gold liras, tripled and has risen to 300. Because the school gives free education, its costs are recouped by a yearly public tax. The Marash disaster of 1920 has destroyed this – so well started – work too. [41]

The Central School, during its three decades of existence has prduced many graduates who have later been the breath and soul of all Marash’s educational, church and social movements. As the mother school of the Armenian Apostolic community, it is impossible to over-appreciate the Central School’s role especially in the nurturing of Armenian education and learning among Marash’s new generation. The name of the Central School in all these ways is linked to the awakening of the enlightenment and education of the Marash Armenian community.

Girl's education

If the work of educating boys has been the subject, to a greater or lesser extent, of care and much special effort was expended in that direction, then girls’ education was not only left to one side, but deemed completely unnecessary, and totally disregarded. This was the reason that, for many years, from the beginning until the 1850s, there has not been girls’ schools in Marash.

To understand and correctly appreciate that girls were distant from school education, it is necessary to keep in mind on the one hand Marash’s social atmosphere and living conditions and, on the other, the Armenian community’s extreme conservatism that has forced it to live if not isolated, then a very self-contained existence to guard against incidents and clashes occurring between it and other peoples. To all this has to be added the patriarchal traditions and customs that created a huge hole in the road to female education. In his memoirs, the Protestant pastor Rev H Djenanian tells us: ‘It is not permitted for girls to go to school at this time; in fact there is no school for them anyway. For a girl to go to school is considered to be unseemly. Sometimes little girls are allowed to bring food to their brothers at school at lunchtime and will glance inside to see what a school looks like. Poor things! How many of them have craved the opportunity to go!’ [42]

Just like in many Armenian-inhabited places, in Marash too, the organising of girls’ education has been an Armenian Protestant kindness. The first Girls’ Central School in Marash has been founded by the Protestant community in 1856. [43] Without doubt a great part in the founding and later operation of both the boys’ and girls’ centres of learning has been played by western missionary organisations, especially by the ‘American Board’s’ financial and moral backing. Thus the need for girls’ schools has been felt, from year to year, to be more and more necessary in Marash especially as the Armenian Protestant example has acted as a spur for the Armenian Apostolic community to have its own special schools for girls.

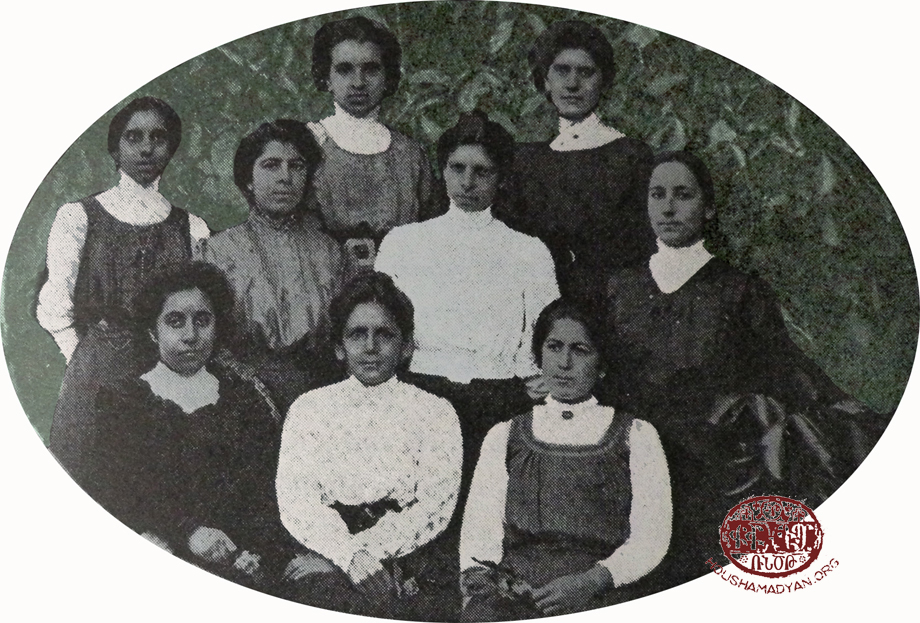

Marash, Central Turkey Girls’ College (American) teachers. Seated, left to right: Maria Alexandridu, Giulenia Mumdjian (later Atamian), E M Blekely, Araxi Kuyumdjian. Standing, left to right: Lusia Kesadjekian, Makruhi Bulgurdjian (later Kumruian), Bessie Hardy (later Lyman), Lusia Mikayelian, Salihe Bademian (later Amiralian), Santukhd Tavitian (later Baghdigian) (Source: Kalusdian, op. cit)

Limited information has reached us concerning girls’ schools, but that small amount is enough to show that the standard of girls’ education has greatly increased from the 1880s, with a great role reserved for the Marash Girls College (Central Turkey Girls’ College) that, although it was an American Protestant centre of learning, is open to all, without sectarian bias, and provides great possibilities for higher education for young ladies graduating from schools. In truth, many of the girls who have graduated from the Armenian Apostolic schools have continued their education in the college, with many of them becoming teachers in Armenian community schools. [44]

The total number of girls attending school in Marash in 1905 is 669. [45]

It is important to point out that Armenian women of Marash have played a great part in Marash’s educational awakening. Among those who are especially remembered are the ladies who were graduates of the Pedagogical School of Istanbul, Mrs Hranush Azadian, Dudu Kesadjekian, Dudu Amiralian and the young ladies Miss Ovsanna Keombedjian, Elmas Saghbazarian and others. [46]

The first Girls’ Central School to be opened within the Armenian Apostolic community is located in the courtyard of The Forty Innocents’ church, the teacher being Rev Stepan. [47] According to various sources, there was a Girls’ Central School attached to that church in 1883, where Rev Ghevont and Miss Sema Kazaz-Hagopian taught. This school has later been moved to a building constructed next to that of the Central School. [48]

An Armenian Women’s Association has been organised by the ladies of the same church who were in favour of female education, having the aim of assisting it in Marash. [49] Its funds are accrued from subscriptions and donations.

Certain married women grouped around this association – Tamam Muradian, Vartig Partamian, Hammal Burunsuzian and others have succeeded in having a building constructed to be a Girls’ Central School in the Central School’s courtyard. [50] In reality this so-called building is a modest, single-storey construction. Naturally, just like all the other schools, this Girls’ Central School also hasn’t continued on a regular basis, due to an irregular budget and other reasons, and has shut down on various occasions. [51]

This school has had, in the 1890s, Miss Ghudzig Der-Ghazarian as a teacher, with Miss Khatun Vartoghlian as her assistant. [52]

A second Armenian Women’s Association has been quickly formed from notable ladies of the St Stepannos church, among whom are ladies from the notable Chorbadjian family of Marash – Mayrig and Elmasd Chorbadjian. It is thanks to this association’s efforts and financial donations that a Girls’ Central School has been opened in the courtyard of the same church, attached to the boys’ school. Its first teacher has been Anna Kazandjian. It is recalled that one of the first initiatives has been to dispense with the wearing, by the girls, of the low, brimmed fez. [53] There are about ten girls being taught in this school in 1875. [54].

Schools have later been opened specifically for girls in all of the six Armenian churches. All of them have Ladies Trusteeships, especially formed to aid girls’ education. [55]

The Armenian community of Marash, numbering about 2,000 houses has, in 1898, two girls’ schools with about 200 students; the first located in the Central School and the second in St Stepannos. Both of them are schools with a complete range of subjects, with the one in the Central School having a slightly higher syllabus. [56]

Armenian Catholic community schools

From the time that Catholicism has entered Marash in the 1860s, Catholic priests have run a school specifically for boys with the aid of choir leaders (tbrabed) and teachers from Marash. Judging by the megre information that is provided by available sources, the Catholic community has its school from the time that Catholic religious services have been held in houses used as chapels. Kalusdian writes: ‘As the Armenian Catholic community has increased, Hagop Agha Chakmakian’s house in Shekerdere has become a chapel, where religious service have been held by Rev Hovhannes Gheverian, often giving pupils lessons there too.’ [57]

The Armenian Catholic community of Marash has its first archbishop in 1865, in the person of His Eminence Archbishop Bedros Apelian. Through his immediate efforts, the community has its own church, the Holy Redeemer, with a boys’ school opening in its courtyard. History assures us that: ‘His eminence the archbishop making superhuman efforts for the sake of the community’s progress, has brought it to a dazzling state in a very short time.’

Apart from a prelature, building a church and schools, by buying many fixed assets, he has secured a firm financial income from several sources. In his day the Mesrobian Boys’ School and the girls’ Immaculate Conception school have been opened that have continued their work until the deportation of the Armenians of Marash. [58]

The Mesrobian Boys’ School

It was said above that the Armenian Catholic community has had a school specifically for boys from the very beginning that has been made into a regular school through Archbishop Apelian’s efforts. Armenian, Turkish and French languages and basic subjects are taught. In the decade 1860-1870 the teachers have been Rev Bedros Demirdjian, Khacher Zulumian, Hovsep Baghdagezerian and, later Dzeron Chakmakdjian, Bedros Der-Hagopian and Dede-Toros Shadarevian. It is recalled that they have all received their education in Marash, and later, through self study, have gained much more knowledge. Dede-Toros Shadarevian has become one of Aleppo province’s most able lawyers and in 1920 has been granted the rank of Count by Pope Benedict XV.

Aerchbishop Apelian has been replaced, in 1877, by Bishop Geghemes Mikayelian who has similarly has worked to the limit of his powers for the prosperity of the community. Giving great importance to the education of the young generation, Bishop Mikayelian has given great impetus to the mixed schools. [59]

In the 1885-1895 period, the directors of the school have been the monks Revs Hovhannes Gedikian, Iknatios Terzian and Levon Kechedjian, who teach Armenian and basic subjects. Among the teachers that are remembered are Toros Mahigian and Hagop Faradjian, both Turkish experts.

The school at this time was divided into two parts – young and older. The little ones are taught by Sarkis Kerekian, Arisdages Sadjonian and Vartavar Adalian, all of Marash, the latter being choirmaster and musician. The older children’s part is taught by Misak and Parunag Momdjian (between 1893-1896), with Armenian and French being taught by the monks Revs Manuel Kalaydjian and Vartan Baghchedjian, both from the Armenian religious centre in Rome.

The teacher from Albistan, Babashanian was invited, in 1902, to be the teacher of Armenian and Turkish, and has continued to do so until 1915, having Hovahnnes Mesrobian of Marash as his assistant.

School expenses are defrayed by the Armenian Catholic community. The school has always been aided by notable Armenians Catholic families and individuals. Those remembered from the initial period are the aghas Mgerdich Keoliuian, Hagop Talatinian, Hagop Gedikian, Kevork Keshishian, Artin Arekian and Artin Akrabian and, later the Kherlakian Effendis and others.

A mixed kindergarten has been opened in 1907 within the community, the directorship of which has been given to the Brotherhood of St Joseph. One nun and three ladies teach the children. [60]

The Hripsimian Girls’ school

The first Armenian Catholic archbishop of Marash, His Eminence Bedros Apelian, has brought a nun with him, Sister Takuhi (from Ankara), who is to dedicate herself to teaching girls. Sister Takuhi has begun work with a few helpers, teaching the children, giving them basic Armenian lessons and teaching them embroidery. This has continued for some time, after which a nun from the order of the Immaculate Conception of Istanbul, Sister Isguhi, then Sister Yermone have come to Marash and, with the assistance of girls who are to become nuns, are driving the work of girls’ education forward.

At the request of Bishop Avedis Tiurkian, the following nuns from the Armenian Order of the Immaculate Conception of Istanbul, Sister Rosa from Istanbul, Sister Prapion Kechedjian of Marash and Sister Theresa Hovnanian of Erzurum have arrived in Marash in 1897. They have established a regular girls’ school named the Hripsimiants Girls’ School. [61] Sister Prapion has studied in Austria and Sister Theresa in France. At the beginning, for the first year or two, the school has even had a boarders’ section, where regular lessons in Armenian, French, embroidery etc have been taught. Several monks also teach geography, mathematics and basic lessons. This has continued until the beginning of the First World War and, during it, as far as possible.

The Hripsimian School, at this time, has 350 pupils; its annual budget is 150 Ottoman gold liras, partly funded by donations and partly by the pupils’ fees. Well-to-do ladies of the community, especially those of the Kherlakian clan, have been this educational establishment’s guardian angels with their important financial donations and with ever form of aid.

In 1919, after the Armistice, Sister Elbis Gabrashian and a few nuns have come to Marash. The others who accompanied her quickly returned, but Sister Elbis has remained in Marash with the plan of realising the opening a girls’ college, but the final 1920 disaster has prevented it.

Armenian Protestant schools

Ordinary schools

Just like the Catholic community, that of the Armenian Protestants, from its early days, has taken special care in terms of educational work, especially as they enjoyed the American Protestant missionaries’ financial, moral and intellectual support. It should be taken into account, however, that from the first steps in the Protestant movement the American missionaries have received great assistance from the Armenian Protestant community. As the Protestant pastor Rev Yeghia Kasuni points out: ‘The Americans would not have been able to build such a wonderful and broadly-based educational setup had they not found such favourable ground and a prepared, active element like the Armenian people, and hadn’t enjoyed the Armenian Protestant communities’ knowledgeable and constantly increasing cooperation.’ [62]

So it is a just and, at the same time, acknowledged truth that, exactly as in all the Armenian provinces, the educational work in Marash too has, proportionally, lived a period of progress as a result of the cooperation between local forces and the missionaries.

From the foundation, on July 1, 1846, of the Armenian Protestant Church, when Protestant communities have been quickly formed in Istanbul and in the provinces, special care has been taken to ensure that every new Protestant community has its own school, of at least a basic standard. The missionaries generally held the idea that the mind as well as the soul should be enlightened, and their greatest efforts have been to get rid of illiteracy and, to do that, the most basic thing is to give the new generation education.

In 1853 when Marash’s Armenian Protestant community numbers barely 20 people, they have opened their first boys’ school with 15 pupils, among who are non-Protestants. In 1885 the number of pupils has risen to 35; the next year 52 and, year after year boys’ education has progressed with great strides within the Protestant community. [63]

The girls’ school has opened in 1856 and is the first one opened, not just for Armenian Protestants, but in Marash generally. In this same year the school has approximately 70 pupils – both boys and girls – of whom 28 are girls. Considering mixed education improper however, the girls have been quickly put into a separate group and a woman teacher, Marinos Amiralian, who can hardly read and write has been appointed. She is learning and teaching at the same time.

It is not superfluous to note here that Armenian Protestant schools, either single sex or mixed, including classes for boys up to 10-12 years old, have been generally given to the care of women teachers, even in centres like Ayntab and Marash. This method of running schools is both economical and easy. This seems to be an American custom also adopted by the Armenian Protestants. Young ladies and married women who have had some education at home both teach and learn. Women teachers are prepared in the girls’ high schools and colleges run by the missionaries. Apart from education in school, the women and young ladies of the small Protestant community visit homes and teach families to read the Gospels.

Thus by 1858 the girls’ part of the school has 35 pupils. In 1861 the missionaries Mrs Goodell and Mrs White (?) have founded, with 13 girls, the first regular girls’ school and have begun teaching. In just a few years the number of girls attending has increased enormously to 125.

The community growing year by year also has three churches with kindergartens and both boys’ and girls’ schools attached to them. Alongside basic education taught in them, special care is taken in moral and religious teaching. The majority of the teachers are graduates of the Marash Girls’ College.

The Protestants also have a school named the Model School for boys, and a prepatory school for girls called the Vusta (Middle) school, where girls are readied for entry into the Girls’ College. [64]

The Protestant pastor (Badveli) Rev Aharon Shiradjian, in an article he has published in 1905, counts the number of children of the Protestant community in school as 1342 (673 boys and 669 girls), with 47 teachers (9 male and 38 female) and the annual school budget as 400 Ottoman gold liras. [65]

It is to be noted that Protestant education has greatly prospered in the decade 1905-1915.

Marash, 1914. Central Turkey Girls’ College (American) graduates. Seated on the ground, left to right: Mayrig Kerigian, Yester Haidostian (later Manugian). Seated, left to right: Repeka Heghinian, Gadarine Giuliuzian, Negdar Djebedjian, E M Blakely, Victoria Sarkisian (later Levonian), Yester Kesadjekian (later Elmadjian). Standing, left to right: Makruhi Bulgurdjian (later Kumruian), Zaruhi Sevadjian, Koharig Mgrdichian, Ovsanna Manushagian, Armenuhi Baghdoyian, Arshaluis Keoteklian (later Senekdjian), Mary Ayvazian, Mariam Magarian (later Chorbadjian), Nuritsa Bardakdjian (later Sareyan), Yepros Djizmedjian, Khatun Balasanian (Source: Violette Djebedjian library collection)

The Marash Academy high school

The Armenian Protestant community’s high school, named the Marash Academy, has opened in 1891 through the immediate efforts of Mr Thomas Davidson Christie, who has become its first director. This high school has been founded with the specific object of preparing students for entry to Ayntab’s Central Turkey College, as the existant school called Idadiye (Ottoman government school) hasn’t got the means to do so. It has been established in Marash in the building constructed for Mr Bibby in 1856.

It is noteworthy that Mr Christie has not only undertaken the founding of a high school, but has been forced to overcome the objections of the other missionaries, who have been against this plan. [66] The first teachers are the Protestant pastors Rev Avedis Bulghurdjian and Rev Aharon Shiradjian; Simon Kiupelian (a professor from Tarsus College); Dr Nshan Amiralian and Hagop Kalemdjian.

The school has improved greatly until the anti-Armenian massacres of 1895. The teachers at this time are Levon Ashdjian, Sarkis Samuelian (both killed in the 1895 massacres), Spiridon Marashlian, Hovhannes Chilingirian, Mibar Mencherian and Garabed Harutiunian (later a senior pastor – a verabadveli). The director is Dr L O Lee. [67]

Lessons taught are Armenian, Turkish and English, general and national history, geography, Algebra, basic elements of the sciences, Holy Bible and composition as well as singing and music. The students are also coached in public speaking, for which a weekly recitation practice is held. [68]

During the 1895-1908 period the following teachers have been teaching: Yeghia Behesnilian (Kasuni), Luder Chorbadjian, George Poladian, Dr Levon Melidonian, Hovhannes Haidostian, Vartan Samanlian, Mihran Kazandjian, Hovnan Der-Bedrosian, Apraham Berberian and others.

According to the written report prepared in 1905 by the senior pastor (verabadveli) A Shiradjian, the school has 5 teachers and 125 students. The first graduates from the Marash Academy have passed out of the school in 1893, and the number of students graduating up to 1905 is 92, of whom many have continued their education in the colleges in Ayntab and Tarsus. Many young people of the Armenian Apostolic faith have also been students. [69]

This high school has continued its fruitful work for 23 years – from 1891 until 1914.

Central Turkey Girl’s College

The second important step in girls’ education has been the founding of a Protestant high school for girls, that has become the college. In 1856, when schools have been running successfully and the number of girls studying has registered growth from year to year, it has been considered suitable to form, in 1865, a girls’ high school under the directorship of Josephine L Coffing. This ‘High School for Girls’, thanks to Mrs Coffing’s enthusiastic work and shrewd governance, has swiftly made great progress. Subjects taught are: modern Armenian, Holy Bible, grammar, mathematics and geography etc. [70] The girls who graduate then go to Ayntab, where they complete the courses in the local girls’ school in two years. A boarding section has been created in Marash, in 1872, giving girls from the surrounding towns and villages the opportunity to study in this high school.

Girls’ education, under these circumstances, has improved from one year to the next, gradually achieving a higher and higher standard, until in 1882 it has reached the standard of a regular college. When the missionaries have suggested that a girls’ college be opened, it has received an enthusiastic reception by the community’s notables. On the occasion of the opening of the college in Marash and the girls’ school reaching college standard, the Protestant notables and community have played their part with important donations: Garabed Agha Topalian has given 125 gold liras, Sarkis Agha Roubian 25, while the community has collected 350, making a total of 500 gold liras that have been allocated at the end of 1881. [71]

Thus in 1882, thanks to the close cooperation between the missionaries and the Marash Armenian Protestant community, the Marash Central Turkey Girls’ College has been established.

The Girls’ College syllabus is similar to that of an American college, naturally amended to take into account local conditions. At the beginning, although special regard has not been given to the teaching of Armenian language, in later years that gap has also been closed, thanks to the Armenian teachers from Marash.

It is important to remember that even after the organisation of the regular college, this educational centre keeps its preparatory section for those girls from various places who apply to be students but do not have the necessary preparation. The college also has a kindergarten attached, where trainee teachers from the ranks of the students of the senior classes can get hands-on experience.

We learn, from senior pastor (Verabadveli) Rev Aharon Shiradjian, that in 1905 there are 89 students in the college, of whom 63 are from Marash, and that the number of teachers is 8 [72]. The students come from Aintab, Aleppo, Urfa, Kilis, Beylan, Adana, Hadjin, Sis, Tarsus, Zeytun, Albistan and many other towns and villages. The graduate students provide great help in their own towns and villages as teachers, especially in girls’ schools. In truth, the Marash Girls’ College has been a blessing for the whole of the Cilicia region, but for the people of Marash in the first instance.

In general we can say that thanks to the college syllabus, Marash Armenian educational-public life has noticeably improved, beginning with the training of teachers, the introduction of new educational and school pedagogical methods, as far as the spread of music and the arts. We should remember that the Girls’ College students sing using European notation, and those with talent learn to play the piano and organ, thus introducing academic music into Armenian homes in this way. [73]

The Girls’ College buildings, set on hill, are immediately noticeable when one sees the panorama of Marash from a distance. These light, airy and beautifully situated buildings have many conveniences. The main building has a well-appointed hall, many classrooms and bedrooms for the boarding students. It also has a playground and a large courtyard planted with flowers. 96 students have graduated between 1885 and 1903, and in this same year (1903) there are 90 students. [74] The college has a new building constructed in 1905 costing 2,000 gold liras.

Marash. Armenian teachers of Central Turkey Girls’ College (American). Seated, left to right: Hermine Amiralian, Rahel Heghinian, Mary Heghinian. Standing, left to right: Giulenia Mumdjian (later Atamian), Yevnige Terzian (later Kasuni), Kayane Kradjian, Lusia Mikayelian, Feride Shamlian (later Hovagimian), Araksi Kuyumdjian (Source: Kalusdian, op. cit.)

The Cilician Theological Gymnasium

Benjamin Schneider, with the assistance of the missionaries located in Ayntab has opened a regular theological gymnasium in Ayntab in 1854 that has been transferred to Marash in 1864. This gymnasium has provided a mixed scientific and theological education firstly in Ayntab from 1854-1864 and then, in Marash, from 1864-1873.

This gymnasium, established in the Akdere quarter of Marash and organised in the same way as previously, has continued with good results until 1872. The students are taught English, Armenian, mathematics, surveying, physics, astronomy etc. After the gymnasium’s transfer to Marash, more importance has been given in it to teaching English and raising its standard to an appropriate level.

The teacher-in–charge at this time is Dr Pratt and, upon his departure for Istanbul in 1867, G.H. Montgomery has replaced him. Later, in 1869, Stephen Trowbridge has taken charge, followed by Henry Perry in 1871. The science department is run by Alexan Bezdjian.

The number of students in 1869 is 30. This gymnasium has students not just from Marash, but also from Ayntab, Albistan, Adana, Kessab, Urfa, Severeg, Diyarbekir etc. [75]

The report prepared by the senior pastor (verabadveli) Aharon Shiradjian gives important details concerning the gymnasium ‘s transfer to Marash. It is interesting to know that, to establish the Gymnasium in Marash, the Protestants of the town paid 400 gold liras in 1868 to the foundation fund. [76] In this way the Armenian Protestant community of Marash has earned the right to be the equal co-owners of this establishment.

The Central Turkey College has opened in Ayntab in 1874 with a science department, thus leaving the Gymnasium established in Marash as a purely religious and theological educational centre. From now on it only accepts those students who are being prepared to be preachers, so steps are taken to raise the level of syllabus to that of a proper Gymnasium, which happens in 1879. This second theological era is made notable by the construction of its first building, and being endowed with a very valuable specialist library. It forms its regular theological department in 1881 with two American and one Armenian professor. However, even after turning into a completely theological school, it has been forced to accept students, who haven’t received a proper college education, with the aim of producing preacher-teachers, for a considerable time.

Some of the graduates of this period are: Prof. H K Krikorian, Prof. Sarkis Levonian, senior pastors (verabadveli) Avedis Bulghurdjian, Hagop Kumruian, Hagop Kundakdjian, pastor (badveli) Sarkis Yenovkian and others.

The real reorganisation of the theological Gymnasium, however, takes place in 1888. A new constitution is established and a decision is made that only graduates of colleges or similar institutions may be accepted as trainees to follow a three–year theological education. [77]

The reorganised Gymnasium has produced its first graduates in 1889, of whom six – the senior pastors Aharon Shiradjian, Bedros Topalian, Hampartsum Ashdjian, Stepan Hovhannesian, Karekin Yessayian and pastors Hovhannes Chilingirian and Stepan Hovhannesian, all of them from Marash, having taken a public examination, all received a permits to preach.

Finally, in 1889, it has been possible to raise the Marash theological Gymnasium to the level of similar gymnasiums in America. The syllabus is for three years. Alongside the syllabus, lectures are also given by teachers and guest activists. From this date the Gymnasium produces graduates regularly every three years.

Preaching permits have been granted to the following people in 1892: Krikor Kerkyasharian, Manug Hagopian, Armenag Haigazian, Levon Soghomeian, Levon Ashdjian, the first three from Hadjin, the last two from Marash. During this period the Gymnasium’s permanent professors are: the American missionaries Dr Thomas Christie, teacher of Hebrew and ancient Greek, church history and explanation of the New Testament; Dr L O Lee, teacher of systematic theology and explanation of the New Testament; senior pastor (verabadveli) Simon Terzian, teaching how to preach sermons. [78]

The students, who are accepted once every three years as a new intake, are looked after by the establishment as boarders, at the same time being able, when the opportunity arises, to practice their preaching in the Protestant churches in Marash and teach in their Sunday schools, while in summer they visit nearby villages and small towns. [79]

As Dr Christie, has resigned from his post in 1895, the Gymnasium has a new permanent professor, the missionary Dr Fred Macallum, who has come to Marash from Erzurum and is an expert in Armenian studies.

The Gymnasium’s governing body in 1914 consists of: senior pastors (verabadveli) J Merrill (Ayntab), J Martin (Ayntab), H Gardener (Hadjin), A Harutiunian from Marash (on behalf of the Cilician Union of Evangelical Churches), D Kundakdjian (Kessab), H Ashdjian (Adana), Stepan Tovmasian (Tarsus) and Dr Shepard (Ayntab). Senior pastor Simon Terzian has invited senior pastor Garabed Harutiunian, who has completed his education in Oxford, to be his assistant.

The Gymnasium is located to the north-east of Marash, in the missionary and Girls’ College compound; it has three fine, high buildings. The pride of the establishment is the wonderful and rich library with about 3,500 valuable books, mostly the newest publications on theological subjects.

The 1914 graduates are last produced by the establishment: pastors (badveli) Asadur Solakian, Yeprem Djernazian, Nerses Sarian, Sarkis Chobanian, Siragan Aghbabian, Dikran Antreasian, Harutiun Nohudian, Simon Vehabedian and Kevork Sahagian. There are also others who attended parts of the courses. [80]

Marash, 1914. The graduates and teachers of the Cilician Theological Gymnasium. Standing, left to right: the pastors Kevork Sahagian, Nerses Sareian, Simon Vehabedian, Asadur Solakian, Siragan Aghbabian, Dikran Antreasian, Harutiun Nokhudian. Seated, left to right: the teachers senior pastors Simon Terzian, Goodsell and Woodley. Seated on the ground, from left to right: pastor Yeprem Djernazian, Sarkis Chobanian (Source: Kalusdian, op. cit.)

- [1] Krikor Kalusdian, Marash or Kermanig and heroic Zeytun, 2nd edition, New York 1988, p. 428. (in Armenian)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, p. 429.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, p. 434.

[6] This is how the Marash notables who were influential, wealthy and ran community affairs were addressed.

[7] It was a Marash custom to call each of the six church parishes tem meaning prelature.

[8] K. Kalusdian, op. cit., p. 434.

[9] Ibid, p. 430.

[10] Ibid, p. 431.

[11] Ibid, p. 492-493.

[12] The six churches that belonged to the Armenian Apostolic community of Marash were: The Holy Mother of God, St Sarkis, St Kevork, St Stepannos, St Garabed, and The Forty Innocents. Each had its parish school which was attended mainly by the children of the parish.

[13] K. Kalusdian, op. cit., p. 435.

[14] Ibid, p. 433.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid, p. 434.

[19] Ibid, p. 437.

[20] Ibid, p. 436.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, p. 438.

[23] Ibid, p. 434.

[24] Ibid, p. 432.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid, p. 562-563.

[27] Ibid, p. 432.

[28] Ibid, p. 492.

[29] Ibid, p. 439.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid, p. 443.

[32] Ibid, p. 492.

[33] Ibid, p. 593.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid, p. 440.

[36 Ibid, p. 440-441.

[37] Ibid, p. 443-445.

[38] Ibid, p. 563.

[39] Ibid, p. 445.

[40] Ibid, p. 443.

[41] Ibid, p. 462.

[42] Ibid, p. 438.

[43] Ibid, p. 446.

[44] Ibid, p. 448.

[45] Ibid, p. 472.

[46] Ibid, p. 534.

[47] Ibid, p. 446.

[48] Ibid, p. 447.

[49] Ibid, p. 446.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid, p. 447.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55} Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid, p. 634.

[58] Ibid, p. 637.

[59] Ibid, p. 461-462, 639.

[60] Ibid, p. 645.

[61] Ibid, p. 463-464.

[62] Ibid, p. 374-375.

[63] Ibid, p. 464.

[64] Ibid, p. 465-469.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid, p. 468.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid, p. 469.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Senior pastor (verabadveli) Yeghia Kasuni, Path of light: a history of the Protestant movement, 1846-1946, Beirut, Lebanon, 1947, p 367. (in Armenian)

[75] Kalusdian, op. cit., p. 477-478.

[76] Ibid, p. 478.

[77] Ibid, p. 478-479.

[78] Ibid, p. 479.

[79] Ibid, p. 480.

[80] Ibid, p. 481.