Palu - Village houses

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 20 Aug. 2011 (Last modified: 20 Aug. 2011) - Translator: Ara Stepan Melkonian

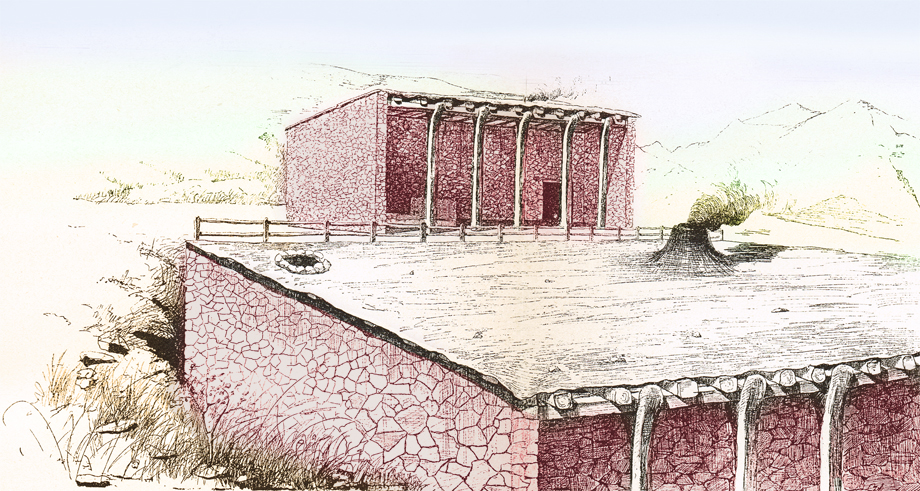

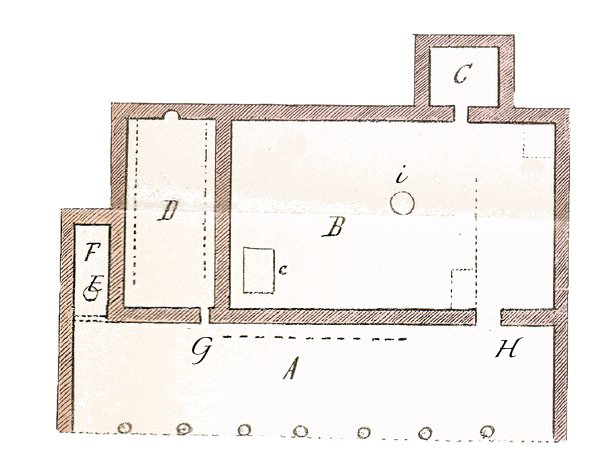

The majority of village houses in the Palu district are single storey. When you enter through the door on the street there is a yard (called a tortan in Palu dialect) in front of you. This separates the actual house and stable that is further in from the street. During the summer the villager’s animals are held in it; this is the reason that it must be relatively big, and the surrounding walls thick and high. The bakehouse, which the people of Palu call tuirezer or tonradun, with its tonir (oven) is to be found in one corner of the yard. This is where flour is used and bread made. It is built about one metre above the ground and occupies a space of 2-3 metres square (6-10 feet). [1]

The potters in Palu are women, so the building of the oven is reserved for them. They use a specially selected clay called gadjghi in its construction. It is considered that the most difficult part of building an oven is giving it its correct shape: in other words it must have a shape that, when a fire is lit in it, the heat will travel to all its internal surfaces, otherwise it is useless. If it is not built correctly, the dough used to bake lavash bread will remain uncooked, not stick properly to the inside walls of the oven and even fall to its floor. If this is the case, the people of Palu say that the oven is anterpe. This word in local dialect is a synonym for death. The oven itself is built below ground level. Its base measurement is generally about 150 cm (5 feet), height about 120cm (4 feet) and the thickness of its walls is 10-12 cm (4-4.5 inches). It is shaped like a basket, with a wide base and narrowing to the top. The woman potter polishes the inner walls with a stone called a gogan weighing about 1.5-2kg (5-6 lbs). Clearly, the inside of the oven has to be smooth so that the bread flour coats it well. There has to be a hole level with the bottom, called a dzordz, which can be opened to allow a draught to flow through the oven to rekindle the fire whenever it dies down. The bread baked in the oven is removed with a long rod with a hooked end. [2]

Another building in the yard is the gshkerdun where stores of wood, dung, paste and gshkuri are kept. [3] Unlike village houses in other places, those in the Palu district have their haylofts or barns built in the yards. Its size is of course dependent on size of the owner’s wheat fields. It is in the hayloft that the straw and other bits left over (used in making mortar) after threshing are stored.

At the far end of the yard from the street is the inner house. This may be entered through a door looking on to the yard itself. In the case of other houses there is a narrow passage between the yard and the inner house itself called a khel. From the cold winter months from December until March the inner house is used as a sitting room and bedroom and its size is determined by the number of family members. It has no windows, but it has a skylight that in Palu dialect is called an ertik in place of them. In extremely cold weather it is closed with a piece of ice about 10cm (4 inches thick) that will remain solid for two days before it melts. Immediately under the ertik is a hole in the floor called a brudj, which fills with water dripping from the ice. The family eats, sits and sleeps in the inner house during the winter. During the day the bedding is piled up, and in the evening it is spread on the floor. The linings for the beds, pillows and coverlets belonging to Palu villagers are made of durable cloth, and one side of the outer covers are made from European fabric, one side plain white, the other printed, locally called bord. These are all filled with either selected wool or cotton. The loom with its pit is also built in the inner house, where Palu weavers produce cloth. It is here too that the women, using spinning wheels (chayr, djakharag) turn wool into yarn. The larder (khezen) is also to be found here, as well as one or two separated rooms, where newly-married couples sleep. [4]

The hearth is likewise built in this part of the house. It is like the oven in shape and built below ground level of clay, but is only half the size. The main difference is that around its open top there are three raised points about 2cm high (about 1 inch) that act, like a tripod, as the points on which the cooking pots are placed to cook food. Like the oven, it is also built by the women. [5] Immediately above it is the chimney, which has a large hole in the roof, and gradually narrows as it rises towards the sky. It is called a pukherig in Palu dialect. [6]

The innermost part of the house and built alongside it is the stable. In Palu this description covers stabling, the sheepfold and cattle shed. It consists of two sections: the inner one, reserved for buffaloes and draught oxen, and the outer part, where calves, cows, horses, mules and donkeys are kept. The sections are side by side and separated by a wall. The floor is made of level stones. Every morning the villager spreads dust made from dung (khushki) over it to a depth of 5cm (2 inches). This is swept out in the evening and a new layer is spread in its place. The animals can lie down in comfort on this. There is a hole in the floor of the stable (called trkpos or brudj) for into which animal waste and the dust is swept. It is emptied twice a day and the contents tipped on the ground, generally near a threshing floor. This takes place during the five winter months, when the animals are kept in the stable. Eventually a whole hill of dung accumulates there, usually higher than the houses themselves, and that can be seen from a distance. It is from this pile of dung that the villager prepares the gshkur in spring that is used to cover the threshing floor. [7]

The stable has a door that opens into the house. In average sized houses the distance from the yard to the door of the stable is 15-20 metres (50- 60 feet). A 2 metre (6 feet) wide passageway is opened along this line, through which the animals enter and leave the stable without disturbing the people in the house.

In the houses of the district the stable also contains the saku, built along one of its walls. This is the room (a little like a garret) which is about 1 metre (about 3 feet) above ground level and is surrounded on three sides by handrails. There is a bench (dakhd) inside it, against the wall. It is in this room that, during the winter, a part of the family takes shelter; it is also the place where various meetings of the villagers take place, during which things to do with the village are examined. This extreme closeness between the stable and the inner house, as well as the family living side by side with the animals has, according to Sarkisian, its health risks. The same author points out that, unlike the Armenians, houses in Palu’s Kurdish villages are built 5-10 minutes’ walk away from the stables, in which a significant part of the Kurdish peasant’s animal stock is kept. In Sarkisian’s opinion, the main reason for this difference in the way the two peoples live is due to the Armenians being concerned about their animals being stolen, something that happens more often in Armenian villages. [8]

How does a villager in Palu build his house?

The owner and the builder together prepare the plan of the house. Then, in accordance with their directions, labourers begin to dig trenches to place the foundations in. These are generally 1 metre (3 feet) deep and 60-70 cm (2 feet to 2 feet 4 inches) wide. It is the custom to sacrifice a sheep or male goat over one of the trenches. Then the builder, reciting an ‘Our Father’ begins to put the cornerstones, cut from large pieces of hard, cut stone, into their positions in the trenches. [9]

Village houses are generally built next to one another, without space between them. The doors are the features that define one house from the next. Houses that are built on a mountain slope are not only built next to each other, but also have a second door on to the roof of the house below, bearing in mind that these roofs are used by the villagers as thoroughfares. The walls of the various inner parts of the house are never subject to rain, so are not made of actual dried mud bricks. On the other hand, the yard walls are open to the sky, so are constructed of large, durable stones. It is the same with the external walls. They are built of stone and up to 2 metres (6 feet 6 inches) high, and parts above that are of dried mud bricks (called karpidj). There are villages, of course, that being away from sources of stone, have to build all parts of their houses of these bricks. In this case, the clay they use is sticky and durable like pitch. It is put into standard-sized moulds, then turned out and put into the sun to dry. It is said that walls built of these bricks last for more than a century. It is only the well-to-do villager that builds the walls of his house using lime mortar. It sometimes happens, however, that being well-to-do doesn’t allow the villager to have a better house. The main reason for this is fear of the Kurdish beys or aghas of the village or surrounding villages. Sarkisian says about this: ‘He [the Armenian villager] can‘t live freely in a house that has beauty and splendour like those of the neighbouring aghas or beys. Just as Hashim Bey of Til village apparently says, his maraba peasants who till the land, instead of seeing shoes, should only see sandals (drekh).’ [10]

The walls of the house are usually 4 metres (13 feet) high, with the roof built on top. For this, thick beams are used which are secured on the tops of the walls, each beam being 2.5 metres (7 feet) away from the next. The size of the house can be determined by the number of roof beams used. Thus the unit of measurement is called magh. If a house has a roof with only one beam, the width of the house is considered to be two maghs; if it has two, then it is three maghs wide; if it has three, then it is four maghs wide. Joists (tugan or gtsag) are then put across the beams, each 20 cm (8 inches) from the next. Then laths (short and thin pieces of timber) are added, secured close together across the joists. Finally pieces of wood or fresh tree branches are put on top. All this is then covered by a layer of mud, a mixture of soil, water, bits of straw, animal dung dust and ashes, about 20 cm (8 inches) thick. This kind of mud becomes very firm and tough, keeping out the rain and snow. After the mud has dried, sieved soil to the depth of 30-40 cm (12-16 inches) is spread all over it, which is then firmed and levelled with a stone roller. The roof is coated with carefully-chosen clay once a year. Part of building the roof is the securing of the projecting eaves. These are pieces of wood, set horizontally at the edges of the newly-built roof next to each other and extending beyond the walls. Their role is to keep the walls from getting wet, and they look like wooden umbrellas fitted to the tops of the walls. These eave timbers are made from the branches of oak or oleaster trees, and are notable for their durability. Semi-circular gutters called gurchivan (also known by other names: gurchrvan, chortan, chrortan and djortan) are fixed to the eaves to take the flow of rainwater from the roof. There is a skylight, looking into the inner house, let in to the centre of the roof. A khachk, a sort of wooden blind, is used to close it, and under which swallows often build their nests. [11]

Certain changes in the design of village houses have begun at the beginning of the 20th century, when those of two-storeys began to be built in the villages in the Palu district. [12] Two-storey houses most often seen in the Armenian villages in the northern part of the district. In the case of these houses, a stone staircase to the roof is built in the yard. It is here that the chardakh or summer house is to be found, where the villager lives from the middle of spring until the first weeks of autumn. While in other places it is made of wood, it is more likely to be stone-built in the Palu district. Preparations are made at the beginning of Spring ‘to go up to the chardakh’ and the women and girls begin to coat the summerhouse walls. To this end they prepare a special plaster, made from clay, bits of straw left from threshing, and liquid animal dung. The walls and floor of the chardakh are plastered with this. Then, after a few days rest, they whiten the walls with a white stone. Two parallel sides constitute the building’s walls. Another (open) side, called aghad, is closed with a ‘curtain’ made of interlaced branches (usually from grape vines). The final side, parallel to the ‘curtain’ is open and looks out onto the inner house roof or yerachk. The chardakh’s roof consists of a wooden covering, with lots of holes through which the heavens may be seen. One or two rooms are made inside the chardakh, in which bedding as well as the items required for daily use by the family, such as pitchers, are placed during the day. [13]

An aderbas is also built on the roof of a village house, in a corner furthest away from the yard and street. It has a perimeter of about 9-10 metres (28-30 feet) and its dung walls rise to about 1.5 metres (4 feet 6 inches). It is roofless, with a door is in one of its walls. It is built by the women, at the end of June, when the rains have finally stopped. They collect the dung, then add straw or other easily burnt material and mix it using their feet. They then make the mixture into small, saddle-like shapes and begin to make the walls with them. Each time they complete a row, they stop for a day or two to allow it to dry and harden under the sun. After completion this construction is kept on the roof until the end of August. During the summer the villager keeps various consumable items in it that have to be in the sun. [14]

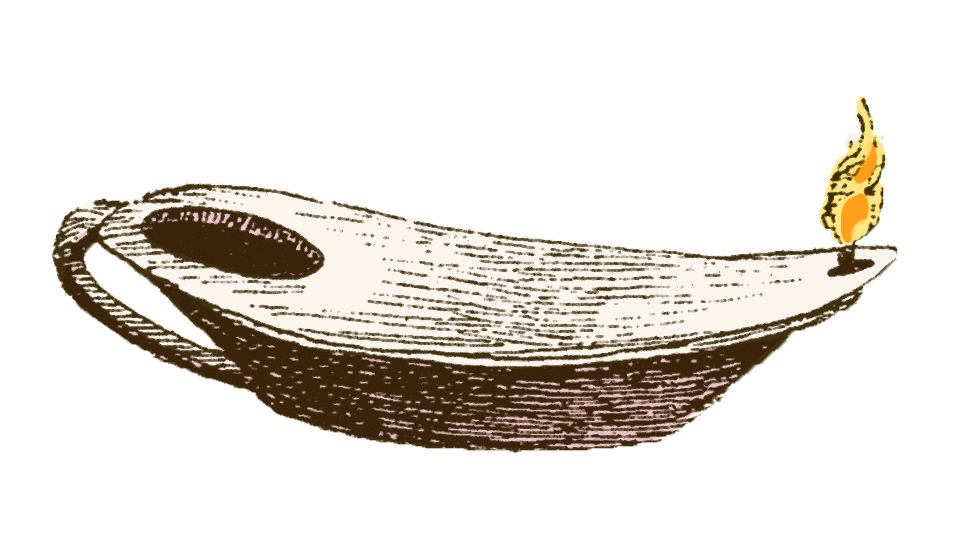

The villager uses a form of lamp to light his home that in Palu is synonymous with the earthenware vessel that has a wide mouth at one end, into which olive oil is poured to fill it. The other end is like a beak and has a narrow opening into which the wick is fitted and lit. Lamps are usually set up on wooden tripods, called djeraktil.

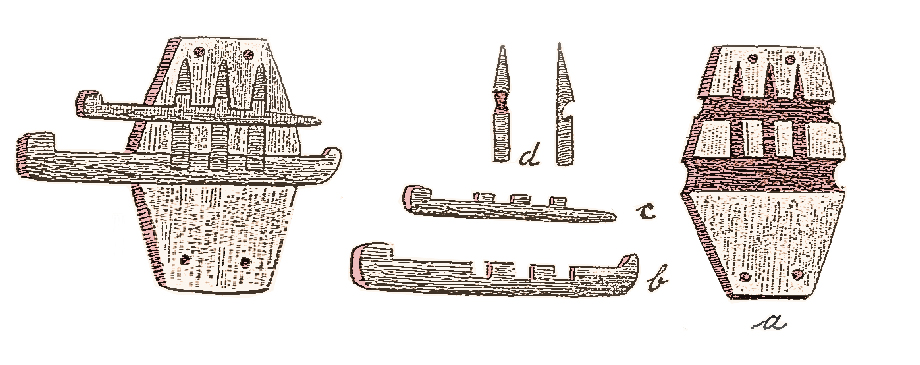

Robberies being frequent, the villager in the Palu district builds a very strong door to the street and keeps it securely locked. In Palu dialect the lock is called a kord. It is a device made from block of wood 40-50 cm (15- 16 inches) long and 30 cm (12 inches) wide which is planed and smoothed. A small hole about 10 cm (4 inches) wide and 5 cm (2 inches) deep is bored in one face into which the tongue of the lock slides backwards and forwards. Two or three further very small holes are bored into it from above, to intersect the first one, and into which small tongues are fitted. The bolt has square shaped cut-outs in it into which the small vertical tongues can fall, thus preventing the bolt’s movement. The door has a hole in it, just above the bolt and parallel with it, for the key. The latter also has cut-outs in it. When it is put into the keyhole, its cut-outs engage with the small tongues which are raised slightly, clearing the cut-outs in the bolt and allowing it to be withdrawn, thus opening the door. Thieves can make duplicate keys, called maze palli, to free the bolt. For this reason the house has a device called kots, which is a large post which is put horizontally across the door on the inside, its ends being secured in slots in the walls on either side of the door. All of this is made of wood. [15]

Further serious changes to the architecture of village houses have begun to appear since the proclamation of the Ottoman constitution. From 1909, two-storey wooden houses painted with oil paints have begun to built in Havav village. In other villages two storey houses made of dressed stone have begun to be constructed. They look like those built in the town of Palu, which have windows and occasionally a balcony. All these things were new in the field of village architecture. [16]

- [1] Rev Haroutiun Sarkisian (Alevor), Palu: its customs, educational and intellectual state and dialect, published by Sahag-Mesrob press, Cairo, 1932, page 235, 238 (In Armenian)

- [2] Ibid., page 211, 360, 443, 451.

- [3] Ibid., page 238.

- [4] Ibid., page 233, 238, 242; Parsatan Der-Movsesian, The Armenian village house, Mekhitarian Press, Vienna, 1894, page 39. (In Armenian)

- [5] Sarkisian, op. cit., page 216.

- [6] Der-Movsesian, op. cit., page 42. Sarkisian, op. cit., page 242-243.

- [7] Ibid., page 205, 206, 208.

- [8] Ibid., page 235, 253, 527.

- [9] Ibid., page 233.

- [10] Ibid., page 233-236.

- [11] Ibid., page 234, 236, 237, 375, 421, 459, 481.

- [12] Ibid., page 235.

- [13] Ibid., page 37, 38, 237, 241.

- [14] Ibid., page 207.

- [15] Ibid., page 379. Der-Movsesian, op. cit., page 48-49.

- [16] Sarkisian, op. cit., page 237.