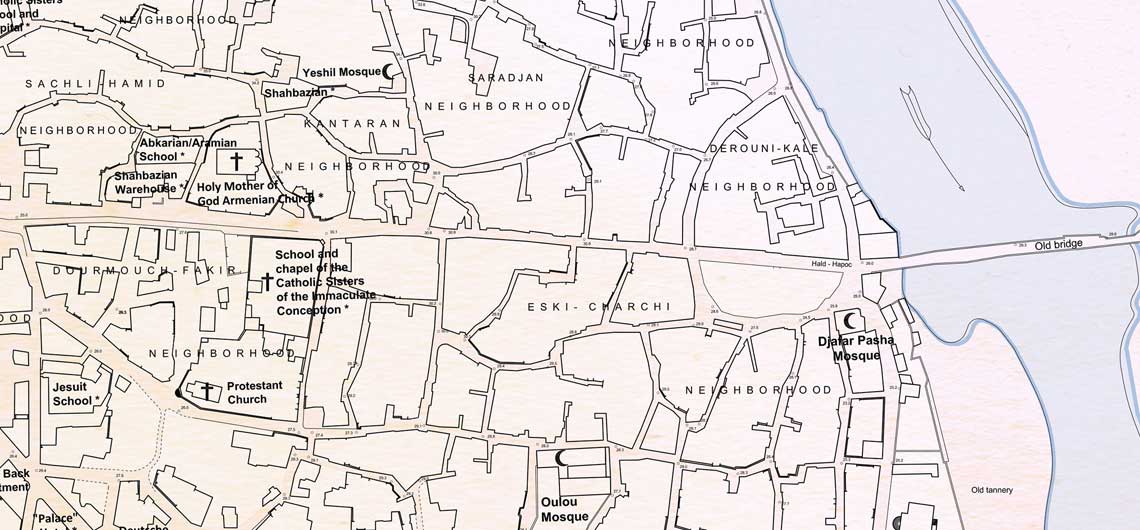

A German Army Map of Adana in 1918

Author: Joseph Rustom, 30/11/2021 (Last modified: 30/11/2021)

This map of Adana aims to depict the city’s morphology and pinpoint its principal landmarks, thereby reviving Ottoman-Armenian life in it in the wake of World War I. It is based on a map issued by the German Army in August 1918, [1] currently available at the Architectural Museum of the Technical University of Berlin and included in the collection of Hermann Jansen (1869-1945), the German architect and urban planner. [2] Having won the competition to design the master plan of Ankara in 1928, Jansen was commissioned to prepare the master plans of several other Turkish cities, including Adana, Mersin, and Tarsus. [3] He probably made use of the German Army map to develop his urban plan for Adana.

Prepared by the German Army just a few months before the entry of Allied (British and French) troops into Adana at the end of November 1919, the original map provides extensive details of the core of the old city center, including the names of all neighborhoods, detailed topographical information in the form of spot elevations, and names of major buildings and their access points. The map also features newer landmarks, such as the new railway station, in the north, and an incomplete thoroughfare connecting it to the center, today’s Ziyapasha Boulevard. Interestingly, although prepared by the Germans, the text used in the map is in French, lingua franca at the time. This was most likely done to ensure that the map was legible to Ottoman officers.

Armenian life in the city was not confined to the main Armenian landmarks and what maps usually indicate as “Armenian quarters.” Nevertheless, Armenian presence in Adana seems to have been concentrated along Ters Kapou, the city’s main east-west axis and former decumanus maximus. [4] North of Ters Kapou, there was a significant Armenian presence in the Bab Tarsous, Sachli-Hamid, Hadji-Hamid, and Kantaran neighborhoods; while south of Ters Kapou, Armenians mostly lived in the Chirak, Dourmouch-Fakir, and Kara-Sokou neighborhoods. A small Armenian population also seems to have resided in the Mermerli neighborhood and in the Idjadiye neighborhood, east of the old railway station. In addition, the map features several plots of land, factories, and a cemetery belonging to the Armenian community. The city’s Armenians also owned several plots of cultivated land that are not marked on the map, mostly vineyards north of the new railroad station and wheat fields on the opposite bank of the Ceyhan/Djeyhan River, south of the new railroad station and near a small village that was a holiday destination for the community. This village was known as Hay Kyugh by the local Armenians and marked as Gavur Köy on some Ottoman maps. The abovementioned Armenian areas and properties also appear on a map of Adana prepared by the French Army in 1920, during the French occupation of Cilicia. [5] The same locations also mostly correspond to the neighborhoods burnt during the massacres of 1909 [6], which included, in addition to all the above-listed quarters, the following areas: (i) in the north-west of the city: Kourou-Keoprou and Taker-Koulpou (both adjacent to Mermerli), part of the Yeni (New) neighborhood, Han-Ghourbi, the city’s Greek neighborhood, and Chinarli; and (ii) south of Ters Kapou and south-west of the bazar: the Ali-Dede, Sari-Takoub, and Eski-Hammam neighborhoods. Some burnt-down neighborhoods still appear on the map as empty plots of land, such as the western portion of the Taker-Koulpou neighborhood.

While this map faithfully reproduces the urban morphology and toponymy as provided by the German Army map, two types of modifications were made to better represent the built environment before 1915. First, the names of buildings to which new functions were assigned after 1915 were changed back to their pre-1915 names. After the deportation of the city’s Armenian population, Armenian churches and institutions were converted into military warehouses and hospitals, as well as Turkish schools. Their original function was briefly reestablished after World War I, during the French occupation of Cilicia between November 1918 and January 1922. [7] On the map, “Dépot militaire (Anc. Église Arménienne)” was changed to “Holy Mother of God Armenian Church,” “Hôpital Militaire (Anc. Collège Américain)” to “American College,” “École Soultanié (Anc. École des Soeurs)” to “Catholic Sisters’ School and Hospital,” and “Hôpital Militaire (Anc. École des P. Jésuites)” to “Jesuit School.” The modified names are marked with an asterisk. Second, the original map was complemented by the addition of the names of several buildings, using other contemporary maps and historical photographs as references. The following locations were added to the map and were also marked with an asterisk: Saint Paul Armenian Catholic Church, Saint Stepanos Armenian Church, Abkarian/Aramian School, Shahbazian Warehouse, Armenian Hotel, Orosdi Back (Department Store), Palace Hotel, Ottoman Bank, Deutsche Bank, and Stock Exchange.

I would like to express my gratitude to Rita Saade for the meticulous reproduction of the original map; Silvina Der-Meguerditchian for the coloring; and Deniz T. Kilincoglu for the proofreading of the toponymy in the Turkish language.

- [1] The survey was performed by [?] and E. Wettstein and approved by Chief Engineer Wintzler [?] in Adana, in August 1918. The scale of the map is 1:1000.

- [2] Architectural Museum of the Technical University of Berlin, Inv. Nr. 23370 to 23381.

- [3] Duygu Saban, “Hermann Jansen’s Planning Principles and his Urban Legacy in Adana,” METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture, 26:2, 2009, pp. 45-67.

- [4] The main east-west axis of the ancient Roman city.

- [5] Croquis d’Adana, 18 January 1920, Service historique de la Défense, previously Service historique de l’Armée de terre, SHAT 4H 231 / d1.

- [6] For the map of the burnt areas, see Puzant Yeghiayan, ԱտանայիՀայոցՊատմութիւն [History of the Armenians of Adana], Compatriotic Union of Adana Armenians, Antelias, 1970, p. 272.

- [7] See Vahé Tachjian, La France en Cilicie et en Haute-Mésopotamie. Aux confins de la Turquie, de la Syrie et de l’Irak (1919-1933) [France in Cilicia and Upper Mesopotamia – at the Gates of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq], Éditions Karthala, Paris, 2004.