Sassoun – Religious Customs

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 04/10/19 (Last modified 04/19/19) - Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

In Armenian primary sources, the Armenian inhabitants of Sassoun are presented as very traditional in terms of lifestyle and beliefs.

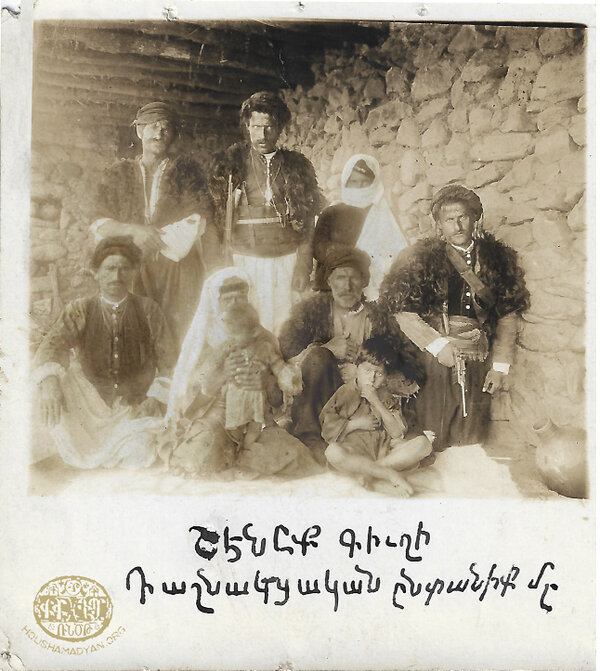

For them, family and family traditions were very important. They were zealous and honorable – reaching a level of being rude and argumentative. They were dear to everyone, if there were no domestic or economic issues involved. But when their pride was wounded, or their dignity offended, when they saw danger, they were completely transformed, and in that moment, they could even kill friend or foe alike without hesitation.

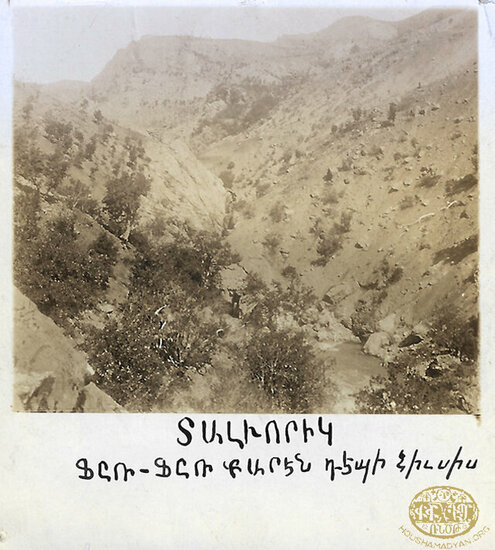

For centuries, their habits remained as steadfast as their mountains; They were the bearers of the national-collective life, at the same time strictly self-centered and tight-lipped about the domestic life of their family. They were industrious, simple people of the mountain, bound to their land and water, mountains and traditions.

No matter how difficult life may have been, they preferred to stick to their ancestral lands. Avoiding clashes with enemies, they took refuge in the gigantic cliffs of mountains and home-built rock, creating natural walls. For the most part, they lived as shepherds, which was rooted in the concept of protecting one's self and one's own flock, taking care of one's own family and clan, and thus of one’s kin. [1]

They were sincere and compassionate, ready to help their community. For those affected by death or natural disasters, everyone around spontaneously assisted as best they could by sharing what they owned. The centuries-long process of mutual assistance was called zoubara. Usually 20 to 150 people would come together to do the hard work, such as building a home, cutting and carrying firewood, bringing and constructing millstones, collecting cattle for food, and so on.

Zoubara was held on Saturdays, so that everyone could rest on Sunday. A few days in advance, the person receiving the zoubara would prepare a suitable meal of yogurt, cheese, bread, meat, etc., and would then inform the people of the zoubara on Friday. Each person would hurry to the work site early in the morning, carrying their respective tools. Together, they would finish the job by evening. Another similar tradition was a form of shared labor, where people would work together, pooling their resources, and then sharing the results once the task was completed. [2]

Relations between neighbors were very close. There were no 'mine or yours' disagreements. It was a natural thing to go to a neighbor’s house and take whatever was needed. Neighbors were always together, whether working, going on a pilgrimage, in times of joy or sadness. People were respectful of one another in public. When greeting one another, people would place their right hand on their breast and bow. Hugs and handshakes were not practiced in Sassoun.

Disputes and misunderstandings were to be resolved quickly, to avoid conflict, revenge and bloodshed. Village elders usually intervened, handing out advice, judgements and proposing forms of reconciliation. However, if the parties remained in dispute, then, on the eve of feast days, before the Holy Communion, the parties would come forward and reconcile.

Hospitality was patriarchal. It was accepted to say, "The guest is God". They were hospitable and respectful hosts, bidding farewell to their guests at the door. Poor people knew for sure that the rich will not reject them. Thus, in times of need, the less fortunate would turn to them. All felt the obligation to help the needy, especially on the eve of holidays. People would share a bit of their meal with the needy before the family gathered around the holiday table.

The moral compass of Sassoun was based on such a sense of mutual support and compassion.

Family

The patriarchal family of Sassoun was large; some 30-40 people lived in one house. Sometimes 60-70 people lived under one roof. The household was governed by the malkho (patriarch) until he reached a very old age.

It was not the custom for the sons to leave home before the death of the elder. They could, if the need arose, build a new house next to their ancestral house, but they would continue to live and work together. Neighbors were often the offshoots of the same clan.

The ruler of the clan was the chopo (grandfather), and the grandmother was called the chocho. The names commonly used for other family members were bab (father), mam/dayo (mother), khalbab (maternal grandfather), khalmam (maternal grandmother), dgha/orti (son), aghchig (girl), abo (father’s brother), harsig (uncle’s wife), khalo (mother’s brother), khalognig (mother’s brother’s wife), hars (brother’s wife), anertsak (wife’s brother), baltouz (wife’s sister), dekr (husband’s brother), dekargin (husband’s brother’s wife), tour (grandchild), toran dgha (great grandchild) and toran tour (great-great grandchild). Sons, with their wives, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren lived under the same roof. Quite often, one could see several cradles rocking for several days at the same time. [3]

The elderly were highly respected. Their opinion was important when making family decisions and they had to be informed about all developments in the house. Women, except for the chocho (grandmother), had no right to speak. Brides or girls were considered the "outer wall of the house". They also had no inheritance rights. There were no divorces in Sassoun. Although a widowed woman could remarry, she had no inheritance, nor was she entitled to take her sons with her. The sons were the heirs of each ancestral family. Thus, parents always strove to have a son so that the family would not die out. Women who had no children would make a pilgrimage. This would involve making a pilgrimage in honor of the saint of their choosing to pray for assistance. In this case, to ask for a baby boy. If a boy was born, the parents would name the baby in honor of the saint. People would utter the following wish to those having no son: May God make your body flower. [4]

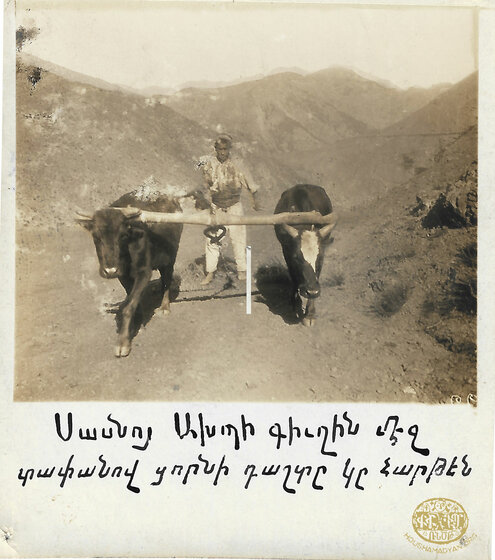

Women usually engaged in field work, but men would assist when needed. Some work - harvesting, reaping, etc. - was the responsibility of women. The men would only do the sowing, watering, tying the bales, transporting and threshing. During the winter months, huddled in their homes, each family had its own workshop, where they would fire dishes, spin thread, make leather, and so on. Each family usually had its own field, herd, garden, and barns. Having no land of their own, poor families would work the land of the rich, thus earning their living.

The tradition was for women and men to eat their meals separately. They would sit on the ground, cross-legged. The dinner table would be placed in the middle, on a small higher table, on which was placed the bread and the large meal-bowl. Each had their own spoon to eat from that common bowl. [5]

They slept on layers of grass or straw, covered with felt. Rugs were used as blankets. Husbands and wives, with their children, lay side by side beneath the one rug. [6]

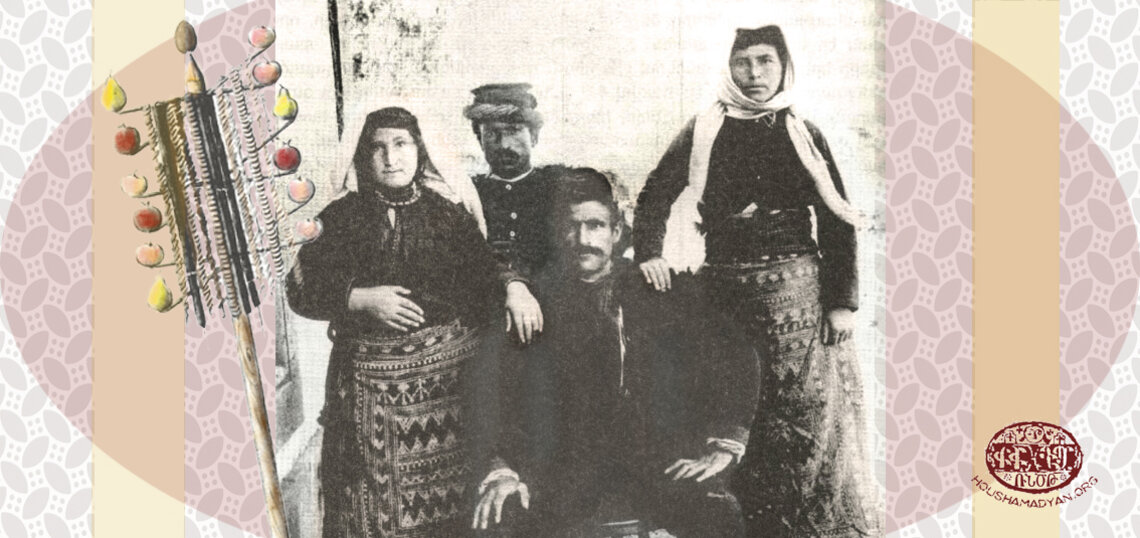

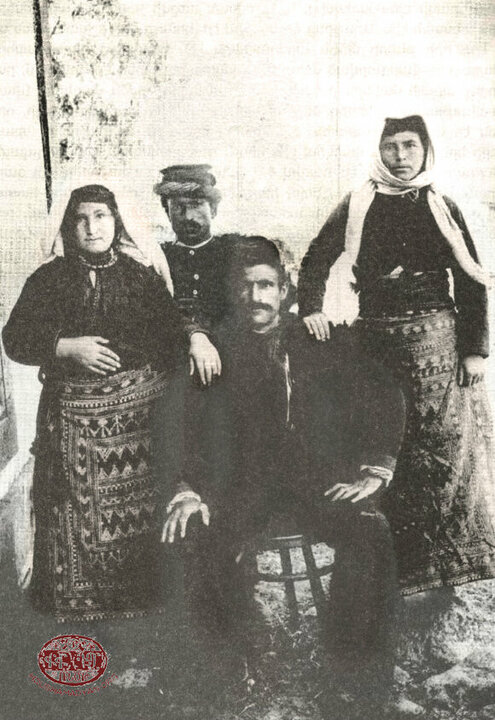

Women mainly wove the clothes worn by the family members. The dress and adornments worn completely changed after one got married.

The family laundry was washed at nearby rivers or springs. People bathed indoors, in the bath house or in the barn.

Before Marriage

It was an old tradition in Sassoun that two women, when pregnant, would promise to become “in-laws” if they had children of the opposite sex. And indeed, when babies of opposite sexes were born, as expected, they would arrange the babies’ engagement while still in the crib. The bond would be made by drawing a khaz (line) on the crib. Afterwards, a degree of intimacy between the families was established. Reciprocal visits were made, always remembering that the children are engaged until the day arrives. [7]

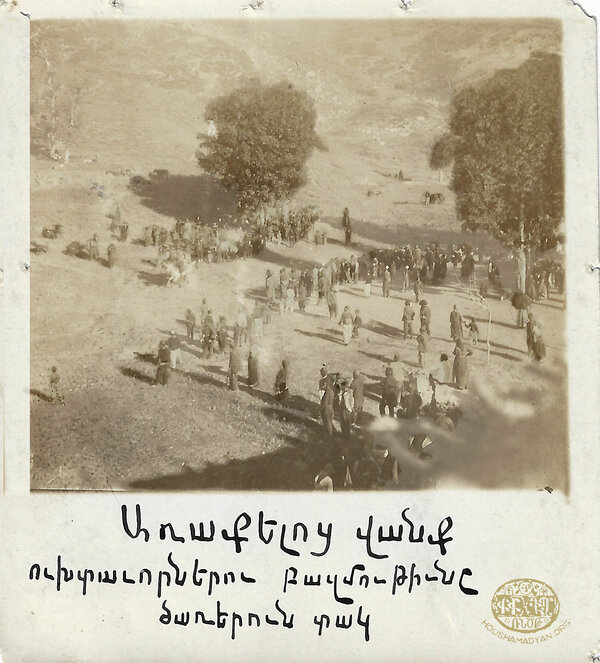

Pilgrimages (and community work) were the best opportunities for young girls and boys to see and fall in love with one other. The girls knit their hair into forty braids, adorning them with colorful bows and placing crowns of flowers on their heads. Feeling shy of their beauty, they would turn red with shame, especially when young men noticed them. Boys wanting to get engaged would say, "The girl who’s ashamed is honorable”. Young people strove to display their strength, agility, and courage in duels, riflery, and feats of ingenuity. Those standing out were mostly boys skilled in hunting and riding. [8]

There was a unique way for a boy to propose to a girl. The boy would follow a girl to the fountain and roll a red apple on the ground. Sometimes, he’d also offer her a pomegranate. According to another custom, at the wedding, the best man would kiss one of the girls on the groom's side as a joke. Naturally he chooses and kisses his chosen girl. This kiss would be decisive for his chosen one. [9]

The love-stricken girl, seeing her beloved, would throw a bouquet of flowers into the water at the fountain. The boy standing below, understanding the girl’s intent, would pick it up it as a sign of agreement. Another expression of pairing would be for the boy to break a girl’s water jug. It served as a remnant of the offering to the goddess of love. [10]

A widespread ritual tradition was for young people to make predictions via the Saints, especially on the feast of St. Sarkis. They would place a piece of dessert on the roof and wait for a bird to come and peck at it. The direction taken by the bird would signal the direction from where their life mate would arrive. [11]

The boy and girl in love, would first reveal their secret to their mothers. If the parents had no objection, they would support the choice. Often, however, parents would not find it convenient. The young people had to obey the will of the adults and thus put an end to their dream. Sometimes, the couple would flee, get married, and seek haven in another village. Later, they would ask their parents’ forgiveness. negotiating with their parents. Usually, after heated argument, the parents would forgive their children and call them home. Sometimes, the parents didn’t forgive their children, renouncing their existence and calling them “lost souls”. Sometimes, the plight of these escapees was even more tragic – for example when the father or brothers would hunt down the disobedient couple and punish them with death. [12] The custom of abducting a girl for marriage was a very ancient tradition, as evidenced by similar incidents in the epic novel Davit of Sassoun. [13]

The average age for girls to marry was 13-15, and for boys was16-18. After turning twenty, girls were considered homebodies and sentenced to marry a widower or to become the second wife of a man married to an infertile woman. According to unwritten law, it was generally accepted that the husband of an infertile woman could bring a second wife home, keeping the first woman as a housekeeper, someone to raise the children and entertain guests, etc. [14]

A precondition for marriage was that the couple should not be closer than seventh cousins. Nevertheless, couples more closely related sometimes married. The practice of giving a klkhakin (head price) was accepted. Needy young men, who couldn’t pay this price, often abducted the girl to avoid payment. But there were times when a girl's dowry was richer than the klkhakin. This led to bargaining and coming to an agreement. Thus, the klkhakin is a more ancient symbolic tradition.

According to tradition, the boy's parents would select the bride and initiate the marriage proposal. However, sometimes the girl's mother made the choice and it was not inappropriate when she sincerely expressed her admiration for the boy and proposed marriage to her daughter. [15]

Although few, there were exceptions when there was no son in the girl's family, or the boy was a stranger or orphan. Under these circumstances, the boy would come to live with the girl's family as the head of the household.

The marriage ceremony had a few stages: the verbal agreement, the engagement, giving of the klkhakin, the ceremony of presenting wedding clothes and presents (gtkhan-khlghat), the wedding (harsanik), marriage, and nuptial chamber. [16]

Khoskgab/Khoskarnoum (Binding Word)

The process of boys meeting girls was done with some secrecy, so as not to draw attention. It was called ouzngan, which literally means “wanting a girl”. Usually, no one except the families knew about it. It was done under the guise of a regular visit. The hosts would prepare a proper welcome, during which the guests (the boy's sides or mediator) opens the door and asks for the girl's hand. The girl's parents would delay the proceedings, claiming a variety of things: the girl is still young, it’s a drought year, a family member has died, a family member is overseas, we are waiting for her, etc.) so that they will not be rejected, but also have time to study the boy's family. Upon final agreement, they agree to perform the khoskgab. [17]

The khoskgab was also done in secret, so that the parties would not feel slighted in case of failure. It was simply a conversation to forge a preliminary agreement to become in-laws. But when the final agreement was reached, the guests put a monetary gift on the table to signal that the khoskgab had been achieved. At the end, they promised each other to keep the khoskgab a secret. From then on, the boy and the girl begin avoiding seeing each other. The girl would try to avoid being seen in the same company. [18]

Nshantrek (Engagement)

The nshantrek/nshandouk (engagement) was also called the hatsgdrel, gesbsag by others. This was the most decisive stage of the marriage ritual. Thus, in addition to the parents, some relatives would also be present. They would invite the head of the village and the priest. Before leaving the boy's house, those arranging the engagement would send a news carrier, called the "fox", to the girl’s home. This person would take a sheep, a can of oil, a sack of wheat, fruit and sweets with him. The mediator, in the role of a fox, had to get to the home of the betrothed in a clever and secretive manner. Otherwise, if the neighborhood kids and old folks found out, they would raise a ruckus and torment him with all kind of jokes. Reaching the girl’s house, the “fox” would report the news that the in-laws were to arrive.

The engagement guests would head out wearing festive attire and burdened with gifts. The girl's parents and relatives would stand opposite those arriving and welcome them. The bridegroom, standing alongside the godfather, would stand outside the door waiting to be invited inside. The girl's uncle, offering sweets, would invite him inside. He would start to enter, but slowly, until his future father-in-law promised a gift, after which the groom would enter and kiss the father-in-law's hand. In return, the father-in-law would kiss the bridegroom’s forehead. As a sign of respect, the bridegroom remained standing. [19]

Guests would be seated, according to age and rank, on flannel sheets and pillows placed on the floor next to the hearth. There were separate rooms for men and women. A general conversation would commence and continue until one of the elders would address the girl’s father and say: "We have come to take a fire from your home to our home."

This expression derives from times gone when a woman sat near the fireplace and kept the fire burning. The father, looking at his wife, would ask: "Woman, you gave milk to our daughter, what do you think?" The mother would respond emotionally: "Husband, let your will and that of those respectful people who have come be done." The father would then turn to the person asking the question and say: "Welcome, a thousand welcomes. May God not shame us. Let it be done."

The "spies", either standing opposite the door or next to the chimney, would then rush to the bridegroom’s house with the news. The repeating refrain on their lips was, "It’s happened. Give the gift of the good news that I bring." [20]

The in-laws would invite the girl in and those at the engagement would bring out the gifts brought to the girl - gold earrings, rings, necklaces. (Each guest would have a gift according to their resources.) The priest would bless the presents and congratulate those getting engaged. The jubilant attendees would utter the following wish - "God be gracious." An old woman would then place the gifts on the girls. The offerings of hospitality would commence. At the same time, a lamb would be grilled, along with other dishes. Wine would be offered, and the table set. The engagement party would last until morning. [21]

Khalangdour (Handing Over Head Price)

The protocol of handing over the khalan (head price) was also called gtkha (gift). However, it was not a gift, but a donation to help the bride’s parents organize a dowry. The amount varied from one to twenty gold pieces, according to resources of the boy's parents. Sometimes there was an argument, but they’d always reach an agreement. [22]

Khlghat (Giving of Wedding Gifts)

After the engagement, the custom was to visit the bride to be. Guests would take gifts and sweets. It was a chance to get acquainted with her. Gifts were usually things that the in-laws would use for the dowry. They would have a long time to prepare before the wedding. The boy’s family would usually help the girl prepare for the wedding by presenting the wedding dress and the dowry fabrics. The giving of these wedding gifts was called the khlghat. It was performed on different occasions and during various holiday visits. It was customary for the boy's relatives, under the auspices of the mother-in-law, to visit the in-laws, each carrying a parcel allotted to them. These parcels contained seasonal fruits, nuts, halva, kata (a sweat bread), a head of sugar (non-powdered sugar), leblebi (roasted chickpeas), dates, fruit paste (basdegh), as well as ornaments, a red yazma (headscarf), handkerchief, etc.

It is also a custom for the bride to go to church, especially on feast days. When the custom of going to public baths took hold, the groom's sister, escorted by girls of a similar age, would take the bride to the bath house. [23]

Then, they would assist the girl's relatives by offering advice when the wedding drees was being sewn. It was preferable and commendable for the engaged girl to do the handiwork and embroidery work, showing her graces. The bride's garments were sewn from expensive fabrics. As the wedding day approached, they would find an occasion to donate a pair of red shoes, a bride’s veil and other things for the bride to wear at the wedding.

During all this time, however, it was forbidden for the boy to go to the girl's house. Meetings, especially appointments, were strictly forbidden and unfavorable for the girl. Clever boys however, in the general confusion when pilgrimages took place, found the opportunity to meet their bride in secret. [24]

Harsnadz (Wedding)

Weddings in Sassoun usually took place after the end of the fieldwork, that is, from the end of autumn to the days of the Paregentan holiday. (The week in February before the beginning of the Great Lenten fast leading up to Easter.)

Although the in-laws would together decide on the wedding day, it was customary that a few days before, a "fox" would again be sent to the bride’s home to inform her about the wedding and the giving of gifts. They would then start organizing a list of honored guests and special participants, called khonti. The first names on the list of invitees were the most prominent in the village. They were invited to special day to hear a singer and lyre player, as well as the “wailing women” in the bride’s home. There were also wrestlers, good runners and horse riders on hand to perform the staged "capture of the groom." This ritual was celebrated in all weddings. There were also bridesmaids (harsnkour/parpoutig), accompanying the bride always until the first night that the bride and groom spent together. And the groom's friends, who were together for the entire duration of the wedding, were called azapchari. Special cakes and small morsels of lamb or chicken, vodka and wine were prepared to invite the special guests. Then, the person doing the inviting would offer these items to the guests. [25]

Friday night was the time for preparations. It was called azapchari kisher. Young people from the community would gather to have fun. [26]

On the wedding day, all the guests and relatives, dressed in a beautiful and festive manner, gathered in the house of the bridegroom before sunset, dined, and then made their way to the bride's house. They did not perform songs, dances, or songs while on the go; only talking solemnly, taking with them lambs for grilling, wheat pilav, oil, sweets, and fruits. They would, by rank, take seats in the home of the bride and engage in light conversation until the sheep were slaughtered and prepared for the wedding meals, served with homemade spirits and wine. After the first dinner, the dancing and celebrations would begin, until the pari luys (morning light) followed by the dressing of bride and groom.

Bathing and dressing the bride and groom was a special ritual in the Sassoun wedding ceremony. After leaving the bride's home, the wedding party guests would proceed with the bathing and dressing of the “kingly bridegroom” in his home. Some youngsters would stay with the bridegroom, like bodyguards, until the wedding night. These guys were called azapchari.

An azapchari and the “king” would be seated in a tub. They would be washed at the same time. But the azapchari would be tormented more, either with hot water or with snow and ice. Constantly screaming, the azapchari would focus the attention of the evil spirits, with a tendency to hurt the king, on himself. After bathing, drying, and wearing the undergarments, they were taken to the center of the hearth room where they sat and were dressed. One of the azapchari guys held the king's garments on a large table. The others, taking the garments one by one and singing the appropriate songs, would clothe the king. Those in attendance would sing the following refrain over and over: "God bless you." They would tie a red and green shoulder sash on the groom. Before placing the takn ou bsag (crown and diadem) on the groom, a clownish barber would approach the groom and shave him. Throughout the whole time, they would come up with comical barriers so that those present could offer gifts (candy, fruit, money) to them. There was also a special song to accompany the shaving:

Ertank choluh, zarkenk gakav.

Perenk tnenk Sourp seghanin

Khern ou parin mer takvorin

Translation:

Let’s go to the pond and shoot a partridge,

Let's bring it and place it on the Holy table,

Goodness and kindness to our King.

The same chorus was repeated, listing the names of hunting birds and wild animals. Then the last part of the dressing ritual was the coronation, when the crown and diadem was placed on the groom’s head. The crown was a hat, with a black scarf wrapped around it. The diadem was a wooden cross, laced with colorful feathers and threads (red, green, white) that served to ward off evil spirits. It was embedded in the hat.

Before that, a genats dzar (tree of life) or ourk would be prepared with the participation of all those present. It was a two-meter length pole with 12 sticks fastened to it in three rows at the same distance apart. There were four smaller poles on each row, at an equal angle. Strings of fresh and dried fruits, cakes and nuts would be hung from the tree. A red dyed egg would be placed at the top. All the home’s riches and goodness would be placed on the tree. It had a ritual significance and would become the target of the "battle". [27]

The guests would sit, side by side, on the floor in a spacious room in the bridegroom's house. In the center of the room on his “throne” would sit the king (the bridegroom). The kavor (godfather) would sit to his right; the azapcharis to his left. The takvori yeres gal "facing the king" ceremony would then begin. Women guests, by the light of candles, would bring in trays of different foods – grilled meats, croissants, cheeses, fresh and dried fruits, cream and butter, honey and yogurt, etc. The azapcharis, accepting them, praise the food and the server, who approaches the groom to kiss him. The party lasts until morning. It’s a joyous feast replete with song and dance and laughter. The wedding party guests then arrive and start the fight to seize the tree. Thus, under the leadership of the senior azapchari, a strategy is devised to protect it.

Regarding the ceremonial protocol for the bride, a few days before the wedding, the bride’s mother had already decided in whose house will the kloukhlval (head cleansing) ceremony take place. It was an honor for one’s house to be chosen for this. Thus, the lady of the house selected would offer special gifts to the bride. The bride would be bathed the previous day, but the wedding dress was worn in her father's home, when the morning light had appeared after the first dinner. The entire population of the village could attend the dressing ceremony without an invitation. While blessing each outfit, they would sing special songs eliciting joy and crying from those in attendance. The feasting and jubilation would continue until dawn. [28]

In the morning, the groom's father (or representative) would ask the bride's parents for permission to take the bride and leave. Addressing the mother, he’d say: "In-law, the milk sucked by your girl is halal (worthy)." The mother would emotionally respond: “Let it be halal, in-law. Let it be halal.”

The father would then slide a gold coin into the hand of the in-law as a gift. The bride and her bridesmaids, accompanied by the wedding party, would then leave the house. They would seat the bride on a decorated horse. Wedding party guests, either on horseback or standing, would surround her, ready for battle. The head of the wedding party would have already worked out with his friends the plan of attack; to surreptitiously approach the king's (groom’s) house, enter through the roof, and capture the king and the tree (ourk).

The “king”, already standing on the roof of the "fortress" house, was flanked by the kavor and the azapchari holding the tree. The other azapchari are lined up on the corners of the roof, defending the “king” and the tree. The troops are lined up to the street, waiting for the approaching wedding procession.

As they approach the king's house, the wedding leader orders the attack. The battle begins. Some use tour ou mardal (sword and shield). Some use canes with hooks attached. Others wrestle or use their fists. Men on horseback rush to the house. The fight continues until the tree is captured. Often, they don’t succeed. This battle for the tree is a remnant of the transition from matriarchy to patriarchy.

However, in all this turmoil, the bride and her entourage remain intact. They approach the “king's” house quietly. At the threshold, they sprinkle coins, dried fruit, raisins and nuts on the bride. Then, the mother-in-law (or another elderly woman) gives the bride a pomegranate or a clay pot to beat the door and ward off any evil spirits. Entering the house, they take the bride to her allocated corner, surrounded by her bridesmaids. It is here that women would approach her to get acquainted. Already reconciled, wedding guests from both sides would enter the house and take their places. At the end, the king enters with his entourage and takes his place. The “facing the king” ceremony is repeated. In the meantime, the singers list the gifts to be given by the king to the bridesmaids and the in-laws. [29]

The wedding usually last 3-7 days, depending on the parties' resources. Then they went to church for the coronation ceremony. On the way, the godfather, wielding a sword, would proudly guide the bride and groom. An azapchari, walking alongside, would carry the tree. At the threshold of the church, the priest and his acolyte would greet the wedding party. The king and the bride would perform the confession ceremony and then enter the church, where the wedding party members were already waiting. After the head and hands of the bride and groom were joined together in front of the tabernacle, the godfather would hold a cross above them. Then, when the heads were moved apart, the acolyte, would take the sword from the godfather and lower it between the hands of the bride and groom, thus symbolically separating their joined hands. Prior to this, the priest and the godfather, by combining threads of red (symbolizing the bridegroom's masculinity) and white (symbolizing the bride's virginity), would form a crown (narod) around their heads, confirming the union of the newlyweds. The coronation ceremony ends with the breaking of the tree (ourk), when the priest picks up the red egg stuck on top of the tree and puts it on the table, saying, "The law has been fulfilled." The priest then distributes the tree to those in attendance. After the coronation ceremony, the priest would go to the groom’s house. [30]

Against the backdrop of joyful music, the wedding party members would sing and dance their way to the groom’s house. On the doorstep, the mother-in-law welcomes the newlyweds, puts bread on their shoulders and kisses the bride, bringing her inside. Approaching, the bride would put her right foot on a copper pot placed on the threshold before entering. Then, removing the loaves from her shoulders, she would throw them to a corner above the room so that bread can be abundant in the house. One of the wedding party members, removing a plate, stolen from the bride’s father’s house, from his garments, smashes it against the wall, thus preventing the bride's potential shortcomings from entering the bridegroom's home. [31] More meals, abundant tables of food and well-wishes follow. At the end of the banquet, the groom and the azapcharis break the dishes on their table. They take the groom and go to their homes. They continue the festivities for another seven days, in different homes. Until then, the bride, staying at the groom’s house with her bridesmaids, adjust to a new environment and a new life.

Excerpts of a Sassoun wedding song [32]:

Transcription:

Zherig khapetsin kureh meh kinov,

Zmerig khapetsin topig meh shilov,

Zaghper khapetsin chughdag meh djzmov,

Zkourig khapestin madig meh hinov.

Zparou hankouts artsagetsin,

Zaghchig mamouts chogetsin.

Merig, mi avler zdakhdig,

Vor chavri kou aghchga hedig,

Togh mna kez nmoushig,

Vor hanes zko srdi hasratig.

Chamich maghov maghetsin,

Aghchga djeber ltsetsin,

Zkharip djampou tretsin.

Tribute to the bride and groom:

Transcription:

Orhne Asdvadz, orhne Krisdos,

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Tsoren tsanen, yeler e pous,

Echmiadzin icher e lous,

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Hripsimen i karsoun gouys,

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Noy Nahabed nsdav kyamin

Ir tserkn arav hats ou kini

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Hatsn ou kinin, der gentanin.

Hisous ichav Hortanan ked,

Yotn anvan der Sourp Garabed

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Bedros, Boghos Frnksdan

Hisous dznav Arapsdan.

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Mer takvorner yegan saren,

Tser takvorner yegan saren,

Karsoun aghpyur pkhets karen;

Orhne ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Sourp arakyal yev markaren

Orhnen ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Karoun yegav, karoun yegav,

Kokn ou dzotse dzaghignerov,

Vordegh nayets, tserke trets,

Ltsvets anoush, knkoush hodov.

Vordegh knats, korker prets,

Hyusvadz hazar var kuynerov.

Gakav yerkets, antsav saren,

Aghpyur pkhets nsdadz karen,

Orhnen ztakavorn ou ztakouhin.

Translation:

- Blessed be God, blessed be Christ,

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- Let them sow wheat, greens have grown.,

- A light has fallen in Etchmiadzin,

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- Hripsimeh and her forty virgins,

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- The patriarch Noah sat in a boat

- He grasped bread and wine,

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- Bread and wine, the master of life.

- Jesus descended at the River Jordan,

- Lord Saint Garabed, of seven names

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- Bedros, Boghos Frnkstan

- Jesus was born in Arabistan

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- Our kings came from the mountains,

- Your kings came from the mountains,

- Forty springs burst from the stone.

- Blessed be the king and queen,

- Holy apostle and prophet,

- Blessed be the king and queen.

- Spring has arrived, spring has arrived,

- Lap and bosom full of flowers,

- He placed his hand where he looked,

- A sweet and soft scent filled the place,

- He laid rugs where he went

- Woven from a thousand vibrant colors.

- The partridge sang, went through the mountains,

- The spring flowed from the stone on which he sat,

- Blessed be the king and queen.

Incense-tree (dzar khngenin)

Transcription:

- Dzar khngenin vor dzaghgetsav

- Toupn ou derev poloretsav,

- Sourp Khach vren vor pazmetsav,

- Takvor, atorkh ourakhatsav.

- Dzar khntsorenin vor dzaghgetsav,

- Toupn ou derev poloretsav,

- Sourp Khach vren vor pazmetsav,

- Takvor, atorkh ourakhatsav.

- Katsek, perek zgakav karen,

- Togh ka mdni tarpazkhanen,

- Sntrig zargin Sourp Seghanin,

- Khern ou parin mer takvorin.

- Katsek, perek zgroung cholen,

- Togh ka mdni tarpazkhanen,

- Sntrig zargin Sourp Seghanin,

- Khern ou parin mer takvorin.

- Katsek, perek zparan chghen,

- Togh ka mdni tarpazkhanen,

- Sntrig zargin Sourp Seghanin,

- Khern ou parin mer takvorin.

- Et inch ou inch, et inch ou inch,

- Dzaghig perink dzaghganats,

- Enbes perink, enbes perink,

- Zdagn ou derev hed irrats.

- Et inch perink, et inch perink,

- Dzaghig perink dzaghganats,

- Enbes tpren, enbes tpren,

- Hars ou pesen hed irrats,

- Ertank cholu, zargenk gakav,

- Perenk tnenk Sourp Seghanin,

- Khern ou parin mer takvorin.

- Ertank choru, zargenk dadrag,

- Perenk tnenk Sourp Seghanin,

- Khern ou parin mer takvorin.

- Ertank choru, zargenk groung,

- Perenk tnenk Sourp Seghanin,

- Khern ou parin mer takvorin.

Translation:

- When the Incense-tree blossomed

- Bush and leaf grew

- When the Holy Cross was placed on it

- The king on his throne was happy,

- When the apple tree blossomed

- Bush and leaf grew,

- When the Holy Cross was placed on it

- The king on his throne was happy.

- Go and bring the partridge from the rock,

- Let him enter from the tarbazkhane

- Sntrig zargin Sourp Seghanin,

- Well-wishes and goodness to our king.

- Go and bring the crane from the pond,

- Let him enter from the tarbazkhane

- Sntrig zargin Sourp Seghanin,

- Goodness and kindness to our king.

- Go and bring zparan chghen,

- Let him enter from the tarbazkhane

- Sntrig zargin Sourp Seghanin,

- Well-wishes and goodness to our king.

- What is that? What is that?

- We brought flowers in bloom,

- In such a way, in such a way,

- Zdagn ou derev hed irrats.

- What did we bring? What did we bring?

- We brought flowers in bloom,

- Let them thus sprout, let them thus sprout

- Bride and groom with them.

- Let’s go to the pond and shoot a partridge,

- Let's bring it and place it on the Holy Table,

- Goodness and kindness to our king.

- Let’s go to the pond and shoot a dove,

- Let’s bring it and place it on the Holy Table,

- Goodness and kindness to our king.

- Let’s go to the pond and shoot a crane,

- Let’s bring it and place it on the Holy Altar,

- Goodness and kindness to our king.

They would also sing this song in Kurdish:

Armenian transcription:

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Հատըն խալխէ դարէ,

Սաքնին աղալարա,

Ժըն բրըն զերէ զարա:

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Խանի բավօ դերա,

Իշաւ ռազէ թերա,

Սըբիէ օղուր խերա:

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Դեկա դա նանպեժա,

Սար սելէ դավեժա,

Հեստա հուր-հուր դռեժա:

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Գազի ապէ կալ կըն,

Նան ու խոյ հալալկըն,

Բուկ լը զավէ բըմբարկըն:

Հայլէ, հայլէ, հայլէ,

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Հատըն լըմ հավալէ,

Բուկ բրըն մեհվանէ:

Հայլէ, հայլէ, հայլէ,

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Հատըն ժը ալի փրէ,

Բուկ բըրն բե բրէ:

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Հատըն ժը բանոկա,

Բուկ բրըն բաշոկա,

Թամամ սուարի քոքա:

Հայլէ լըմ հավալէ,

Հայլէ, հայլէ, հայլէ,

Մագրի բուկէ սալէ,

Դըլ խարիբէ ժարէ:

Translation:

- Woe to me friends,

- Foreign peoples came,

- The aghas waited,

- They took a woman in yellow gold.

- Woe to me friends,

- Your father's house is a monastery,

- Sleep satiated today,

- In the morning, safe travels,

- Woe to me friends,

- Your mother is a baker,

- Let her shed tiny-tiny tears.

- Woe to me friends,

- Call the elderly uncle,

- Let him make salt and bread halal,

- May the bride also enjoy the groom.

- Woe to me, woe to me, woe to me,

- Woe to me friends,

- They took the bride as a guest,

- Woe to me, woe to me, woe to me,

- Woe to me friends,

- They came from the bridge,

- The brother-less bride was taken.

- They took the turtledove bride,

- All of them were horse riders.

- Woe to me friends,

- Don’t cry, bride of one year,

- Gharib, heartbroken.

Mezkekhil (Nuptial Night)

In the Sassoun vernacular, mezkekhil was the name given to the first nuptial night shared by the newlyweds. On the seventh day after the marriage, the king (groom) returns home with his entourage. The mother embraces her son by kissing his forehead and leads him home, where the table is already set. This is the last celebration. The groomsmen (azapchari) offer their well-wishes and leave. The groom thanks them and sees them out. After giving their presents to the bride, those present also leave. The bride kisses everyone's hands and expresses her gratitude and humility. The mother-in-law removes the boy's crown and diadem and puts it on the newlyweds’ bed. Then the elderly bridesmaid instructs the bride, saying, "First, bow your head to God, then to your husband." Then, the bridesmaid pushes the groom towards the bride, and says, “Grow old on the same pillow.” With this, she closes the door.

Outside, men are shooting their guns. It’s to announce the good news and to frighten off evil spirits. [33]

The next morning, the bridesmaid enters their room first and, gathering the sheets, shows the sign on the sheets to the mother-in-law. For this, she receives an appropriate gift. She and the best man go to the home of the bride to report the good news. [34]

A week later, the bride's mother would go to the in-laws’ house to bathe the girl. The dowry will also be brought. Therefore, before this, the mother puts a dollop of halva on some round cakes (kata) and sends them her female acquaintances and relatives as an invitation. The godfather sends a chicken and a lump of sugar. The women's group attends the ceremony of handing over the dowry. The gifts are shown one by one. The godfather also sends gifts. Women guests also give presents. The groom’s mother, in turn, sees the guests off by giving appropriate gifts. [35]

The dowry is usually placed neatly in trunks when handed over. The dowry may be expensive or average, depending on the family’s resources. But some bedding (sheets, blankets, pillows), baby cribs and accessories are a must. Also, according to one’s resources, up to 12 shirts, socks, underwear, knee-length garments, aprons, heavy and light headgear, housecoats, face veil, face kerchief, etc. One work shirt, a few work vests and a jacket must be made. Also needed are two pairs of shoes, a pair of low-heeled shoes for the house, and slippers. Add to the list some embroidered handkerchiefs, napkins, soap, mirror, bathmats, potholders, and sewing accessories. As for jewelry, one silver or gold-plaited belt, one gold-plaited comb, one head comb adorned with coins, and so on. If they are not wealthy, then the jewelry is either glass or bone. [36]

The bride wore her veil for a month, until they came from her father’s home, with great preparations, to take the new bride” back”. It was accepted that the bride’s brother or uncle was the one who took her back. On this occasion, he was given a precious gift, usually a dagger with a white handle. When sending the bride back, they were given food for the journey and gifts for the in-laws. Upon entering her paternal home, the veil was removed. Neighbors, friends and relatives came to see the bride and get to know her. She stayed there for 15-20 days until they’d arrive from the groom’s home to take her back. They took food, which was distributed to passersby, on the return trip. [37]

From the nuptial night to the “taking back” of the bride, she was not allowed to do any strenuous housework. But when she left the nuptial bedroom, to show her diligence and humility, she began to sweep the house. And after the "taking back," she participated in all women's work. As a rule, a Sassoun bride wasn’t talkative. She could talk to her husband only after a few months, and in private. First, she started talking to the little ones in the house, then to the other members. She had the right to speak with her mother-in-law after the birth of her firstborn. She never spoke to her father-in-law.

After the wedding, the bridegroom wouldn’t visit his mother-in-law for a long time until a dinner in his honor was organized. On this occasion, the groom made his first visit with gifts. In turn, members of the bride's family would take him into their home for a few days, honor him, and then send him on his way with gifts of expensive clothing. [38]

On their first Dyarnentarch (Presentation of the Lord) feast day as a married couple, the newlyweds would go to the church and circle the fire seven times to receive the holy fire’s blessings of fertility. [39]

Birth (Dghaperk)

After the wedding, the new bride would not visit the home of a pregnant woman for 40 days, fearing that she might meet the evil spirits there and thus endanger her fertility.

Generally, husband and wife would not have any bodily contact with each other on Wednesdays, Fridays and Sundays, since it was considered a sin according to Armenian Church canon, which the Sassoun Armenians upheld for centuries. [40]

In general, infertility was derided by society. Therefore, when a pregnancy was late in coming, couples kept their infertility a secret and resorted to various acts of sorcery. They would visit fortune tellers and go on pilgrimages to the Sultan of Moush St. Garabed Monastery, and the to the Monastery of Mount Marout. The women went to the village of Untskar and pass through a stone with a hole in the middle. There has been an interesting ritual since ancient times. Together, couples would bring water from seven spring, heat it at night, sit naked in a basin, back to back, in front of the fireplace, and pour water on each other, thus freeing themselves from the "bonded" state, which was regarded as a cause of infertility. [41]

Divorce was not allowed in Sassoun, even in cases of infertility - man or woman. Women were the “honor and zeal” of the Sassoun man and the family. "A woman's words do not fall to the ground" was an adage. Spouses were linked with deep love and respect and shared the hardships of their lives.

A pregnant woman was not allowed to go into the water, cross over running water, enter a dark room, or leave the house at night. The belief was that evil may "strike" her if she did. There was no concept of artificial abortion. Abortion, for whatever reason, was perceived by women as a great sin and crime.

There were various schemes to determine the sex of an unborn child. They would put a small bowl of dough on the fire. If the ball swelled without breaking, then the child is a boy. If it cracked, then a girl. If it cracked emitting a noise, then it would be a strong boy. A pregnant woman would take a boiled chickpea and press it with her fingers. If the kernel flew out without splitting or squashing, it would be a boy, otherwise a girl. [42]

It was believed that when a pregnant woman felt the first movement of the baby, the newborn would resemble whatever the mother saw at that moment. Thus, they would warn the bride not to look at ugly and unpleasant things. [43]

To avoid difficulties during childbirth, they would attach a scissors to the pregnant woman's back with a thin chain, believing that with this magic the evil spirits escaped. A crown (narod) formed of the remnants of a candle lit on Palm Sunday would be tied under her clothes. A baseball bat (shaped like a candle-lit candle remnant) is tied to a garment underneath. They would also tie a thread to her back made of seven knots brought from Jerusalem, Etchmiadzin and St. Garabed Monastery in Moush.

If the birth was late in coming, they would take the plough out of the house and take it apart on the doorstep so that the "harvest" could be separated from the mother. The door of the church (or house) would be thrown open and shut three times to open the door for childbirth. It was believed that prior to childbirth, when a husband touched his wife's back, he strengthened her and allowed the woman to rely on him. But there was another goal here – to divert the attention of the wicked spirits from childbirth to make the pain lighter. [44]

When the childbirth pains began, two women would grasp the pregnant mother under the arms and walk her around the house, to facilitate the delivery. The delivery itself was usually done with the woman crouched on her knees, with an experienced midwife at her side. When the baby is born, after cutting the umbilical cord, they would wash the infant, sprinkle it with salt, wrap it in swaddling, and place it besides the mother’s bed pillow. They would then stick a needle in the placenta and bury it a place where no one treads.

The mother would drip her milk into the baby's eyes to prevent eyesores. Usually, they would feed melted fat and honey, khavidz, greens, fried eggs and halva to the mother to restore her strength and to make sure she produced sufficient milk.

News of the birth would be reported by the children waiting in the yard of the house. If the baby is a boy, they would naturally receive a great gift. The father would not come near his wife and newborn until the fortieth day. However, the women neighbors and relatives would come to celebrate the glad tidings, bringing fabric for the infant’s clothes and kata, cooked chicken, halva and sugar for the mother. [45]

For the first forty days, they’d wrap a shawl around the head and back of the new mother, and a scissors to her back as a charm to ward off the evil spirits. They’d place a dagger under her pillow for the same purpose. They’d also place a Bible or a St. Gregory of Nareg prayer book under the pillow as well, if they had any. They’d also place a metal object in the bathtub of the newborn. Removing the child out of the water, they’d spit in the water and say, "Let the evil go and the good one come."

Only after the child’s baptism would the mother and infant be cleansed and considered halal (acceptable/worthy). Thus, they would strive to baptize, at church or at home, a newborn not later than the first week after birth.

A unique occurrence in Sassoun was the birth of a child born during the time of Red Easter. Such a child was regarded as a pechurar; a fortune teller. They would sacrifice a lamb on such occasions, take the animal’s backbone and pierce it and then give it to the new mother. She would take the bone, place it by her bosom and thus feed the newborn in such a fashion for seven straight days. They’d then take that bone to the field and bury it in such a manner that buds of wheat would emanate from it. Once the wheat grew, they would carefully harvest the wheat and prepare a special flour to feed the infant as the first meal after breast milk. It was believed that such a child would grow up to be a fortune teller. [46]

Baptism, Anointment and Karasounk (40 days)

As was customary, the Armenians of Sassoun baptized their newborn within seven days of birth. Usually the godfather was a clan member, and the position was heredity, passed from generation to generation. He was regarded as the most honorable and intimate person in the household. As a sign of respect and reverence, the godmother never talked to him. She could only address the godfather after his death, when he was lying on his death bed. That is, if she had any last words for him.

To invite the godfather to a baptism, or on feast days, the mother-in-law would send him a valise, a sack full of gifts, containing a hat, a shirt, a handkerchief, decorated socks, kata, a beverage, etc. And godfather would send the godmother red slippers and headscarves, and fabric and other necessary items for the godson. The accepted relations between the kavor (godfather) and the sanamayr (godmother) come from ancient time.

The people of Sassoun would call the Milky Way (Dzir Gatin) constellation the sanamor erduh (godmother’s field). According to tradition, when the godmother fled carrying the straw (hart) stolen from the house of the godfather, the wind blew the straw up into the heavens and thus was formed the godmother’s field. (Another word for the Milky Way, in Armenian, is hartkogh – derived from the words hart (straw) and kogh (thief). [47]

The godfather holds the baby in hid outstretched arms during the baptism. When the priest places the infant in the water, the godfather utters his name. After being baptized, the baby is wrapped in new swaddling and then the priest anoints parts of his body with miuron (holy oil) and chants a corresponding prayer. At the end, the priest blesses the narod brought by the godfather and slips it on the child’s neck. The baptismal narod is made by twisting red and green silk threads and fastening t fringes of the same color to the ends. Red and green are usually a symbol of joy and healthy life. Thus, Sassoun inhabitants, when exchanging well wishes, would say ganuchnas (literally, “may you turn green”), signifying a long and healthy life.

The godfather then distributes monetary gifts to the priest and midwife. He then draws water from the baptismal basin to deliver it to the godmother. This water, mixed with bath water, is then used by the new mother to wash herself so that she too can become halal and be allowed to approach the infant and feed her. Before this happens, the mother is regarded as unclean. People don’t interact with her nor eat from her plate.

Upon returning home, the baby slept in a new crib made for him. He had been sleeping at his mother’s side. On the cradle they’d hang toys (khujkhjig) made of small metallic objects. As they move, they bump into each other and give off ringing noises. [48]

The family then gathers for a “baptism meal”. If the newborn is a boy, especially if he is a firstborn or an only child, they will also prepare a madagh (sacrifice) and bake new bread, eat harissa, pilav, fruit, wine and sweets. If the child is a girl, they prepare a more modest table, considering the girl the "outside wall" and the boy, the "pillar of the house."

The ceremony of bathing the child seven days later is called meronahanek. The basin is filled with water, the child is bathed, and the miuron is removed.

Afterwards, the midwife and new mother wash their hands with that miuron water. They then would sprinkle clean dirt in the water, knead the mixture, and make balls to be used later for purification purposes. For example, when a midwife is to deliver other children, she would place those balls in water and wash her hands. Or when a mouse falls in the basin, it is washed in the same way.

During the first forty days, the new mother does not go out in the sun, nor stays in a dark room. The lamp must be lit at night. The Bible and the dagger remain under her pillow as guardians. After forty days, the restrictions are lifted. The priest reads a special prayer and removes the dagger and scissors. The baby and the mother are no longer vulnerable. They bathe the mother and the husband is permitted to sleep alongside his wife and child.

In the first months, if the growth of the newborn was insufficient, people believed that the child had been touched by evil spirits (karsnkagokh). They gathered millet flour from seven houses, make a dough, and bake a large unleavened bread. They’d remove the middle of the bread, leaving the outer part. They would pass the infant through the bread three times. The middle of the loaf would be dissected into small parts and distributed to neighbors, relatives and the poor. A small portion would be left for the parents. Of course, the priest had to read prayers. Sometimes, the parents would seek the advice of a fortune teller. [49]

Child Care

While the new mother returns to her daily routine, the baby is always under her care. If her milk was plentiful and not fully consumed by the child, the mother would drip her milk on the fire in the hearth, on running water, or on un-treaded clean soil. While rare, there were times when the child of a mother with inadequate milk was given to another mother for breastfeeding. In such a case, the infant was considered the child of the breastfeeding woman. Children who breastfed from the same mother were considered “Milk brothers or milk sisters” and could not marry. [50]

If a new mother had insufficient breast milk, the baby would be fed with goat or cow milk. The mother would breastfeed her child for at least one year. Sometime later, the child was also given a mixture of roasted millet flour and manna. The mother took various steps to wean the baby off milk. She would rub ash or pepper on her breasts to make breastfeeding unpleasant. They would also feed the infant kata and yogurt instead. Sometimes, the mother would go to her parents' home for a few days to stay away from her child and thus have the baby forget about breastfeeding.

Breast milk was considered a medicine, especially for eye pain and diseases, for both adults and children.

Children under one year of age were bathed every day. Like Armenians in other regions of the country, Sassoun residents also put fresh roasted soil in the cradle of a child.

They would tie beads (knhloun) to a baby’s neck, believing it would give the child a peaceful sleep. A button (orachik) was sewn on the chest on the child’s shirt to ward off evil spirits. To speed up walking, the father would prepare a small three-wheeled cart for the child, to lean on while trying to walk.

After shaving a boy's hair for the first time, the hair was shoved in a crack in the wall of the house so that no one would trample on them, thus causing a headache for the child. If it was an only child, the parents would vow to cut the hair for the first time at St. Garabed Monastery in Moush. On this occasion, they’d organize a pilgrimage and sacrifice. When the infant’s hair was cut for the first time, the parents would carefully hold on to it and that the cutter with a gift. [51]

Sassoun Armenians would start abbreviating their names when still children. Only after getting older would they begin to be called after their baptismal name. Examples of such shortened names are Mosé, Bedo, Giro, Kalo, Mouro, Tsouné, Nouré and Zaré.

The rearing of minors was the duty of the patriarchal family; boys aged 4-5 were trained in outdoor work, becoming shepherds or bringing food and water to field workers. Later, boys would ride horses, cut wood, learn riflery, do field work, and more. Girls would learn housework, help women clean the house, bake bread, carry water, collect greens, patch, needlework, milk animals, and so on. Until adolescence, little boys and girls played together and went together to the fields. As they began to grow older, they would gradually avoid intimate conversations and each one would revert to spending time with the elders of their own gender.

There were no doctors in Sassoun, but rather folk physicians (hekim) and fortune tellers (krpats). Both were sought after equally by the sick. The fortune tellers were known for their magical abilities. By writing tought ou kir (spells) they were believed to be able to prevent evil and cure various ailments. In times of sickness, a Sassoun Armenian would also seek the assistance of prayers, talismans, pilgrimages and sacrifices.

Hekims did not believe in the power of the fortune tellers, only in their surgical instruments and herbal medicines. They used remedies handed down over the centuries, from generation to generation. Relying on the knowledge of medieval folk medicine, they developed their abilities and helped the local people recover. They took advantage of the botanicals provided by the rich surrounding environment. They performed surgical procedures, repairing broken bones and preventing a variety of illnesses. [52]

Adamhadig (Baby Teeth Ritual)

The appearance of a child’s first baby teeth was the cause of a ritual ceremony called adamhadig. Wheat grain and chickpeas were boiled and raisins mixed in. They’d place the child on a rug and put different objects in front of him/her: a dagger, a pen, a comb, a small plowshare blade, a shuttle (an important part of the loom), etc. All the other kids in the house would sit around the unfolding spectacle. One of the adults would then pour the boiled grains on the baby's head as the other children hastened to separate out the chickpeas and raisins to eat. When the child came to from the barrage of the dripping grains, he/she would automatically grasp one of the objects. The belief was that the first objects grasped would turn out to be his/her future profession.

Similarly, a ceremony was observed when a child’s first baby tooth fell out. The child would bury the tooth, which he/she removed, at the doorstep of the house. The child would then open and shut the door while uttering the following words taught by the mother - Mandr-mandr guts karan. Khayim-khayim guts djoroun (Small like a lamb’s tooth. Strong like a mule’s tooth). [53]

Death and Burial

Sassoun Armenians believed that God sent an angel who took the spirit of the deceased, entering through the chimney and assuming the appearance of a personage familiar to the deceased. The deceased’s spirit would leave through the nose and, together with the angel, would exit through the chimney.

When a person was dying, they would give him/her water and change the position of the body so that the face was facing the east. Sometimes, at the request of the dying person, they would take him/her outside to see the world one last time. The dead person’s eyes are closed with this intention too, so that "he will go quietly, and his eyes would not remain fixed on the world and his friends." [54]

The dead would be bathed in the yard of the house. They would then bring the body inside and wrap it in white linen, after tying the big toes and hands together with string. They would leave the face open and place a nshkharh (consecrated bread), wrapped in a cloth, on the mouth. Then, they would tie a long cloth on the back, as a belt. Another piece of cloth would be tied, like a cross, on the chest. This was called a khachpoug. Usually, wealthy people would order coffins for the deceased. Those with meager means would be buried wrapped in a shroud. People would take the body away on their shoulders. If the deceased was a famous person, musicians would be paid to play doleful music. During the funeral procession, the women mourners would wail and praise the deceased. (This was their function.) Women relatives would cut their braids and rip their clothes, accompanying the deceased half the way. It was deemed disrespectful to the deceased for men to cry. Menfolk would put their hats on askew and follow in silence. If the deceased was a man, they’d often put his weapon and dagger on the corpse, escorting it to the grave. If the deceased was of a princely rank, men on horseback would follow the coffin. The funeral ceremony also included the firing of guns.

There was no “official” gravedigger in Sassoun.

Every male Armenian considered it his duty to participate in digging of a grave as a sign of respect. They would lay stones on the floor of the grave, then lower the coffin (or corpse) into it. In some areas, it was customary to bury his favorite tools and clothes with the deceased. Stones would be placed on these items. Such burials were called kareh tapout (stone coffin) [55] Blessing a handful of dust, the priest would pray, "You are earth, you become earth. Earth to the earth, the soul to God. Blessed be your soul."

The mourners would then approach and shovel dirt into the grave. Some would throw coins in the grave. After the funeral, all those present expressed their condolences to the relatives, who in their turn invited those present to come to their home for a requiem meal.

The next morning, women would visit with grave with incense and candles. They wouldn’t bake bread or cook meals for a few days in the home of the deceased. Neighbors would take care of such things. Women and men would tie black bands on their heads until the khungi yertaluh (incense leaves). On the seventh day, they would go to the grave, taking incense and candles again. Returning from the grave, the requiem meal would be ready. All the people in the village would come to share in the meal. They would bring different dishes with them. In the evening, as guests depart, close friends would remove the black ties on the heads of the mourning family members as a sign of "coming out of mourning."

To commemorate the memory of the deceased, the family would send a dish of food and two loaves of bread to a poor family. On Sundays, they’d send the same the same to the priest. [56]

When a young man died, his widow would mourn for several years. If the woman's relatives came to the deceased’s home, carrying grilled meats, kata, bread, and wine, it meant that they wanted to marry off their unhappy girl. Thus, after dinner, they’d ask the household members to let them take the girl with them. The relatives would agree to the widow's second marriage. Very often, in honor of the deceased, the wife is married without a wedding party.

Of course, the gossipers would always spread the news that without waiting for the husband's (or wife's) bones “to rest”, the spouse is marrying again.

The deceased's family treats their ex-bride's new husband as a relative. He is given the name of a surrogate. [58]

- [1] A. Kalantar, Sassoun, [in Armenian], Hovhannes Mardirosiants Printing House, Tiflis, 1895, p. 15.

- [2] Y. Garabedian, Sassoun, [in Armenian], HayBetHrad, Yerevan, 1962, p.68.

- [3] Vardan Bedoyan, Sassoun, [in Armenian], Nakhabem Publishing House, Yerevan, 2016, p. 417.

- [4] Ibid, page 423.

- [5] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 81.

- [6] Ibid, page 82.

- [7] Rafig Nahabedyan, Marriage Habits and Rituals of the Aghtsink Armenians, [in Armenian], Yerevan, 2007, p. 33.

- [8] Ibid, page 37.

- [9] Ibid, page 39.

- [10] Ibid, page 42.

- [11] Ibid, page 43.

- [12] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 87.

- [13] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 30.

- [14] Ibid, page 59.

- [15] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 427.

- [16] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., p. 75.

- [17] Ibid, page 67.

- [18] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 429.

- [19] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., p. 79.

- [20] Ibid, page 69.

- [21] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 429.

- [22] Ibid, page 431.

- [23] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 95.

- [24] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 431.

- [25] Ibid, page 432.

- [26] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 106.

- [27] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 440.

- [28] Ibid, page 434.

- [29] Ibid, page 446.

- [30] Ibid, page 450.

- [31] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 90.

- [32] Bedoyan, Sassoun, pp. 434 - 444.

- [33] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 165.

- [34] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 453.

- [35] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 94.

- [36] Ibid, page 90.

- [37] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 454.

- [38] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 92.

- [39] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 165.

- [40] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 457.

- [41] Ibid, page 454.

- [42] Ibid, page 457.

- [43] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 93.

- [44] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 457.

- [45] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 95.

- [46] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 458.

- [47] Ibid, page 460.

- [48] Ibid, page 461.

- [49] Ibid, page 462.

- [50] Ibid, page 462.

- [51] Ibid, page 464.

- [52] Ibid, page 466.

- [53] Ibid, page 463.

- [54] Ibid, page 477.

- [55] Garabedian, Sassoun, page 115.

- [56] Ibid, page 116.

- [57] Bedoyan, Sassoun, page 480.

- [58] Nahabedyan, The Aghtsink Armenians ..., page 53.