Rodosto (Tekirdagh) – Schools

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 24/06/19 (Last modified 24/06/19) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

During this period, the rapid and widespread growth of the Armenian school network, and its expansion from cities to provincial centers and villages, was nothing short of impressive. In a short period of time, Armenian schools were established all across the empire, some of which were institutions of the highest quality. Notably, these schools were supported entirely by the efforts of Armenian communities, without any public funding. In fact, they were sometimes opened in the teeth of overt official hostility.

The yearning for learning and the desire to create a large network of schools did not appear overnight in the Ottoman Armenian consciousness. Naturally, it was the result of a process, and there were many Armenians who opposed the introduction of educational methods considered “modern” into Armenian communities. There was also much internal opposition to the education of girls, as well as to the notion of mixed, coeducational schools. But once the belief in the importance of education took hold among the people, the process suffered no major setbacks. On the contrary, the number of schools, their enrollment, and the number of qualified and competent teachers grew year over year, alongside developments in the schools’ pedagogical methods.

There seems to have been a conscious effort by to link the cultural, intellectual, and scientific development to schooling. This belief spurred Ottoman Armenian communities to spare no efforts to develop their educational systems, regardless of the lack of public funds earmarked for this purpose. Soon, the high quality of education received by Armenians set them apart from other ethnic groups within the Ottoman Empire.

The network of Armenian schools spread all across the Empire. When we compare the development of Armenian education in different localities, we notice similarities and identical processes of growth. Still, regional differences and factors also played their part in the development of the educational systems in different areas. There are countless examples of this. The presence of American missionary institutions in a given city often spurred the establishment of non-missionary schools in the surrounding area. This is an illustration of the benefits of competition. In other areas, rapid economic growth and the existence of international trade gave birth to a highly educated populace, as a result of the demand for workers with knowledge of foreign languages and accountancy practices. In such areas, the local elites readily encouraged the establishment of high-quality educational establishments.

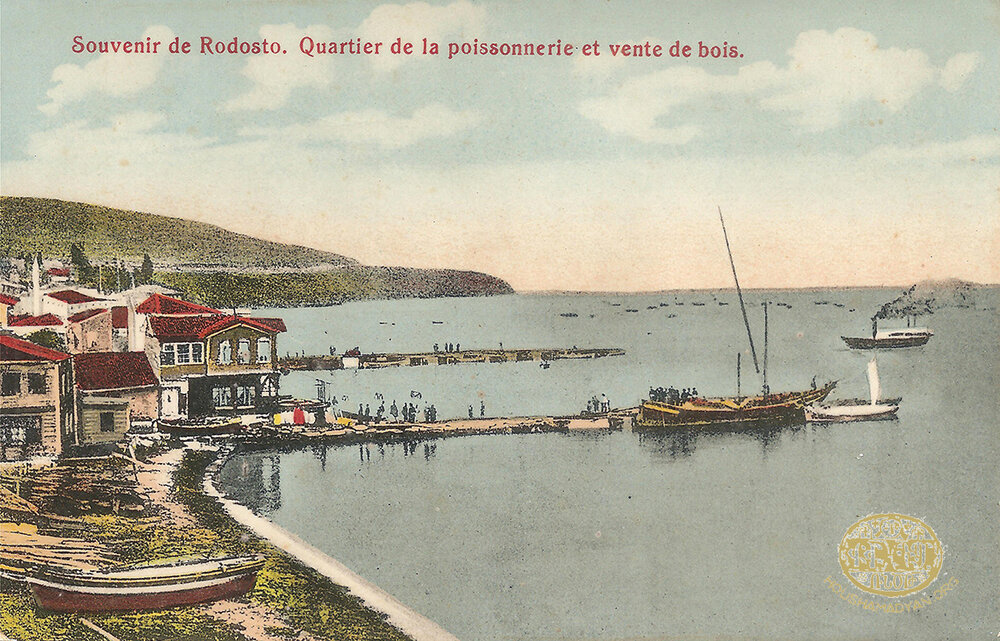

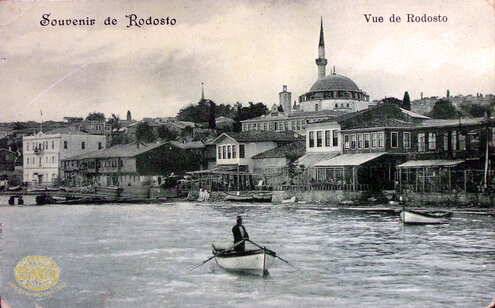

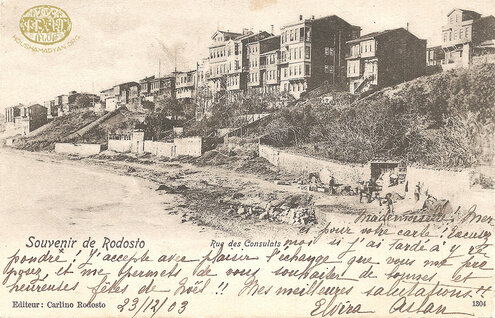

In view of these various considerations, we now focus on the main subject of this article, the Armenian schools of Rodosto (Tekfurdağı/Tekirdağ) Province. The Armenian population of the province was concentrated in its main cities (Rodosto, Chorlou, Malgara, Silivri). The total Armenian population of these cities was more than 10,000. This was not a large population compared to other Armenian-populated areas. The city of Rodosto was home to several high-quality Armenian educational institutions that produced successive generations of graduates. To illustrate this fact, it is important to mention the names of some of the most celebrated teachers who worked in Rodosto and the other cities of the province, as well as the names of some of their more prominent students. Among the teachers were Melkon Gurdjian (Hrant), Levon Shant, Mihran Askanaz, Haroutyun Gelibolian, Krikor Srents, and Kevork Mesrop. Among the notable students were Vazken Shoushanian, Parsegh Ganachian, Ardashes Haroutyunian, Kevork Papazian, Roupen Sevag, Onnig Nevrouz (Nevrouz of Khanasor), Mihran Dadikozian (Abel), Mgrdich Takemdjian (Yeritsants), Garo Ghazarosian (Mehian), and Louiza Papazian. These individuals all played important roles in Western Armenian life, both in the Ottoman Empire and, later, in the Armenian Diaspora.

In other words, this area, which at the turn of the 19th century was home to only a handful of Armenians, boasted a rich and quickly developing educational field. This resulted not merely in a generation of educated Armenians, but also a period of enlightenment that led to a cultural revival, as evidenced by the activities of local theater companies, musical bands, choirs, and literary meetings.

Rodosto lacked missionary schools. Therefore, the origins of the area’s superior educational system must be sought elsewhere. Most probably, one of these factors was the city’s proximity to Istanbul. This meant that the vibrant Armenian cultural life of the capital had its impact on Rodosto and inspired the locals to emulate their metropolitan compatriots. Proximity also meant ease of travel. Many of the graduates of Rodosto’s schools matriculated in the institutions of higher education of the capital, then returned to their native city and launched their teaching careers or other careers. Conversely, the Armenians of Istanbul often visited Rodosto in large numbers, on pilgrimages and on other occasions. Clearly, Armenian cultural developments in Istanbul had a significant influence on Rodosto, particularly on the development of its educational system.

The Armenian Schools of the City of Rodosto

The city of Rodosto had two Armenian neighborhoods – the Holy Cross (Khach) and the Holy King (Takavor). Each of these neighborhoods had a functioning parochial school, attached to the local Armenian Apostolic church. These two schools were often in fierce competition with each other, which only contributed to the improvement of the quality of education they offered. Aside from these two, the city was also home to several other schools, which we will examine separately.

Many families were not content with the basic education offered to their children by the Armenian schools in Rodosto. Consequently, many of these schools’ graduates continued their education in schools elsewhere, particularly in Istanbul and Bardizag. Many of these students also went on to receive university education, sometimes in Istanbul, but also in Europe and the United States. It was perhaps the proximity of Istanbul and its schools that deterred the people of Rodosto from establishing their own secondary school in their city.

The Hovnanian School (Holy King Neighborhood)

This school, located in the Holy King neighborhood of Rodosto, was founded in 1866. It was called Hovnanian in memory the Saint Hovhannes Church, which was located in the same neighborhood, and had burned down in 1864. Some of the funding necessary to build the school came from the sale of the church’s estates. The school included a kindergarten, an elementary school, and a primary school. The subjects taught were Armenian, Turkish, French, national history, mathematics, natural sciences, geography, and singing [1].

According to figures from 1903, the Hovnanian School had an enrollment of 563 pupils and a faculty of nine teachers [2].

The principals of the Hovnanian School were Halfian (1866-1867), Tatarian (1867-1871), Kevork Shiridjian (1871-1876), Reverend Garakian (1877-1880), Melkon Gurdjian (Hrant) (1881-1886), Father Vahan Hagopian (1886-1888), Haroutyun Gelibolian (1888-1892), Levon Shant (1892-1894), Kalousd Antreasian (1894-1895), Roupen Manavian (1895-1897), Mihran Ananian (1897-1899), Sarkis Srents (1899-1903), Misak Sourian (1904-1908), Drtad Tahmazian (1908-1909), Jirayr Basmadjian (1909-1911), Roupen Manavian (1911-1913), Mamas Mamasian (1913-1914), Hrant Antreasian (1920-1921), and Roupen Manavian (1921-1922) [3].

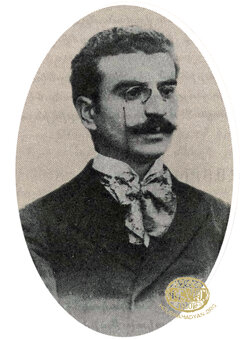

The Hovnanian School experienced its heyday from 1881 to 1886, under the leadership of Principal Melkon Gurdjian, better known by his pen name Hrant [4]. Sarkis Srents (Sarkis Hovhannes Kledjian), who also served as principal of the school, was one of the founders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, Dashnak Party) chapter in Rodosto [5]. Another member of the ARF was Levon Shant, who served as principal of the school from 1892 to 1894, and who would later become a prominent playwright and cultural and community activist.

Beginning in 1880, the Association of Armenian Women was active in the Holy King neighborhood. Its activities included supporting the Hovnanian School [6].

In the 1880s, Armenian teenagers from the Holy King neighborhood organized a fundraiser, and with the proceeds purchased marching band instruments from Istanbul. This resulted in the establishment of the Rodosto marching band, which had approximately 40 members, many of whom pupils of the Hovnanian School. The band leader was Donabedian. This marching band participated, on several occasions, in the competition of marching bands held in the garden of the Istanbul National Hospital as part of the commemorations of the declaration of the Ottoman National Constitution. Several times, the band won first prize. The marching band continued its existence until 1922 [7].

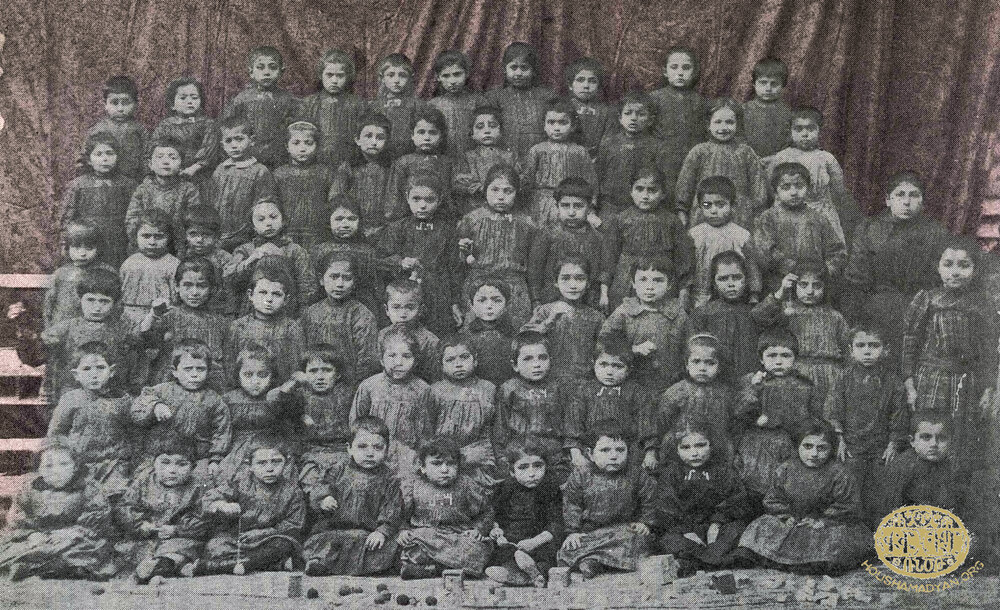

1) Rodosto, December 20, 1915. Mrs. Akabi (seated, in the center), teacher at the Hisousian School of the Holy Cross neighborhood, with a group of her students (Source: Sarkis K. Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun 1606-1922 [Memory Book of the Armenians of Rodosto 1606-1922], Beirut, 1971)

2) Rodosto. Haigouhi Djamdjian, a teacher, with a group of her students (Source: Sarkis K. Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun 1606-1922 [Memory Book of the Armenians of Rodosto 1606-1922], Beirut, 1971)

Another organization, the Ararat Youth Club, was also active in the Holy King neighborhood. In the 1920s, this athletic organization experienced a period of growth thanks to the encouragement of the Hovnanian School. This owed much to Sarkis Srents’ being the school’s sports coach at the time. The Armenian General Athletic Union (HMEM) also established a scout troop in the neighborhood, which organized a march on the holiday of the Nativity of Mary. At the time, the principal of the Hovnanian School, Hrant Antreasian, was also the leader of the scout troop. In 1921, the troop had 35 members [8].

During the Armenian Genocide, once the Armenian population of Rodosto was deported from its native land, the Ottoman authorities requisitioned the building of the Hovnanian School and turned it into a Turkish orphanage. At the end of 1918, when surviving Armenians returned to the city and began the process of rebuilding their lives, the Turkish words Zukur Eytamkhane – Bismillah (boys’ orphanage) were still painted on the wall at the school’s entrance. Another source (Teotig) states that the school was taken over by the authorities during the war and used as a public hospital. The school was reopened as an Armenian institution and remained open until 1921 [9].

Notable teachers (both male and female) of the Hovnanian School included Garabed Hampartsoumian (1899-1903), Hovhannes Yerganian (until 1895), Nounig Der Ghevontian (born in 1885), Filor Batmazian (born in 1895, later Tanielian), Isgouhi Svadjian, Isgouhi Adjemian, Arshaluys Adjemian, Melkon Gurdjian (Hrant), Mihran Askanaz, Haroutyun Gelibolian, Father Kegham Yeldezian, Father Tateos Poryadjian, and Levon Shant [10].

The renowned author Vazken Shoushanian attended the Hovnanian School from 1911 to 1915 [11].

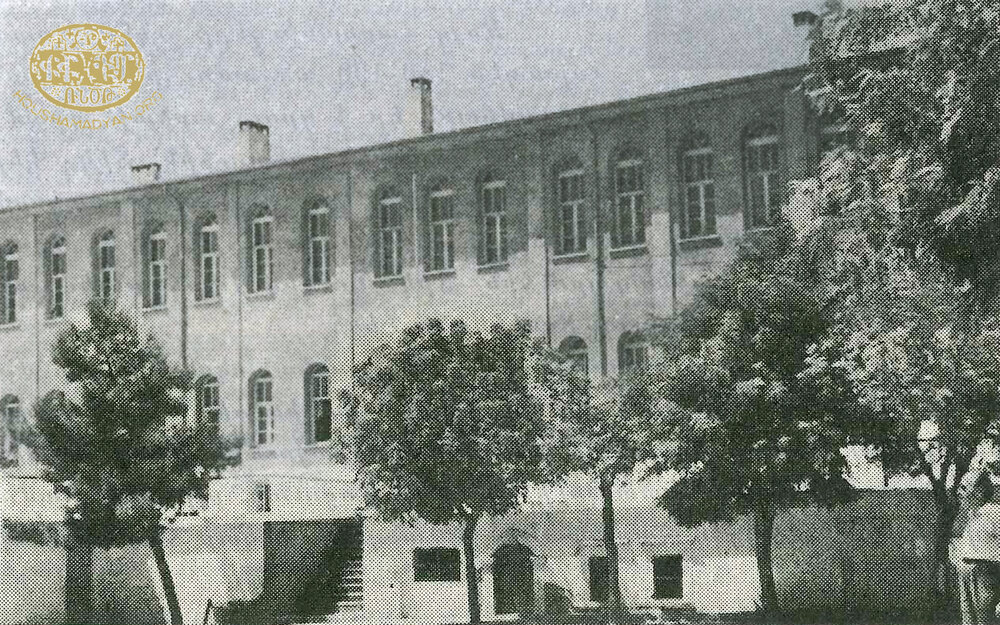

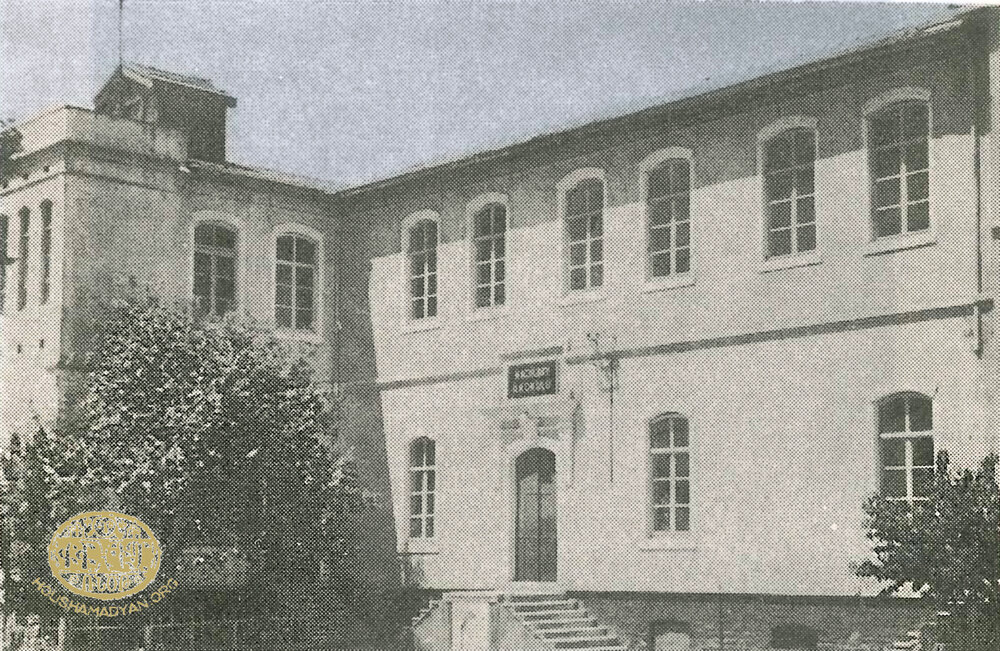

The Hisousian School (Holy Cross Neighborhood)

The Hisousian School was located in the Holy Cross neighborhood of Rodosto. Its exact date of founding is unknown. However, we know that the institution existed by the second half of the 1860s. We also know that until 1893, the school was housed in a building built of wood, which partially burned down in that year. A new building was built at the same site. Like the Hovnanian School, the Hisousian featured a kindergarten, an elementary school, and a primary school. The main subjects taught were Armenian, Turkish, French, national history, mathematics, natural sciences, geography, and singing [12].

According to figures from 1903, the Hisousian School had an enrollment of 293 pupils and a faculty of seven teachers [13].

The school’s principles were – Father Ghevont (1869-1871), Reverend Kevork (1871-1873), Father Arisdages (1873-1874), Mihran Askanaz (1874-1876), Father Hovhannes Armarouni (1876), Melkon Gurdjian (Hrant) (1876-1877), Arsham Mouradian (1879-1880), Roupen Manavian (1886-1889), Shavarsh Yesaian (1889), Hovhannes Yegenian (1890-1896), Roupen Manavian (1896-1899), Dikran Baghdigian (1899-1904), Roupen Balian (1904-1906), Yervant Kevorkian (1906-1907), Roupen Manavian (1907-1908), Kevork Mesrob (1908-1911), Ghazaros Haladjian (1911-1912), Sarkis Emirzian (1913-1915), and Sarkis Manougian (1920-1922) [14].

Beginning in 1882, a board of trustees operated in the neighborhood. The aim of this board, among other things, was to support the Hisousian School [15]. Another organization that was founded in the neighborhood, in 1909, was the local chapter of the Red Cross Women’s Association, which also provided support to the school. This same association organized theater performances in Rodosto. One of these performances featured the first woman in Rodosto to appear on stage [16].

Notable teachers (both male and female) of the Hisousian School included Apraham Hayrigian (born in 1863), Siranoush Baldjian, Roupen Balian (from Talas), Parantsem Balian, Roupen Manavian (born in 1865), Isgouhi Svadjian (began working at the school in 1919), Father Kegham Yeldezian, Reverend Sarkis Manougian (1919-1922), Father Hagop Nazarian, and Father Kapriel Begian [17].

Following the example of the Holy King neighborhood, the Holy Cross neighborhood established its own marching band, whose members were students of the Hisousian School. A European band leader named Guze was invited from Istanbul, and he led the marching band for four to five years until the 1895 Hamidian massacres, after which the marching band ceased to exist [18].

In October of 1912, during the Balkan Wars, Rodosto was captured by Bulgarian forces. All schools in Rodosto were closed down, and the Hisousian School was converted into a barracks for the Bulgarian army [19].

The renowned author Vazken Shoushanian attended the Hisousian School from 1906 to 1911 [20].

The Haigian School (Armenian Protestant)

Armenian Protestants opened their first school in Rodosto in the Holy Cross neighborhood in 1855, in the same building that housed their meeting hall. The school’s first teacher was Apraham (Khosrov) Mouradian. He was succeeded by Movses Mgrdichian and Yeprem Sarkisian. Later, in 1863, Protestant Armenians built a second meeting hall in the city, this time in the Holy King neighborhood. Alongside it, they also built a girls’ school, under the direction of Yeghisapet Mgrdichian. She was succeeded by Takouhi Papazian. In 1864, the girls’ school was relocated to a more suitable building, adjacent to the Peshtimaldji neighborhood.

Due to financial difficulties, these two schools were forced to shut down in July 1895 and May 1896, respectively. The boys’ school was reopened in August 1896, with M. H. Kouzou-Kebabian serving as principal. The girl’s school was reopened in September 1898, with Satenig Ouzounian serving as principal [21].

According to figures from 1903, the combined enrollment of the two Protestant schools in Rodosto was 89 pupils, with a combined faculty of four teachers [22].

Some sources identify the Protestant boys’ school as the Haigian School. M. H. Kouzou-Kebabian served as the school’s principal for long years. Part of his salary was paid by a missionary organization.

In 1902, enrollment at the boys’ school was 40 pupils, of whom only five were members of the local Protestant community. The subjects taught included Bible studies, catechism, general history, ethics, natural sciences, mathematics, geography, Armenian, Turkish, and English [23].

The graduates of these two schools usually continued their education in the Protestant colleges of Bardizag or Adabazar.

Among the notable teachers who served in the Protestant schools of Rodosto up to 1903 were Hovhannes Garabedian, Garabed Djermagian, Hovhannes Kouzou-Kebabian, Hovhannes Erganian, Haroutyun Sdepanian, Haig Chavoushian, Takouhi and Pipe Kouzou-Kebabian, Armaveni Sarkisian, Pailadzou and Yeprasine Malkhasian, and Mannig and Satenig Ouzounian. All of these teachers were natives of Rodosto. Among the teachers invited from the outside were Hovhannes Gaydarian, Sarkis Kasabian, Lemuel Sahagian, Melidos Aydenian, Ghazaros Diradourian, Samuel Kendigian, Hovap Arabian, Mariam Sdepanian, and Nectar Tavitian [24]. In later years, Reverend Sarkis Manougian also taught in these schools [25].

The Gelibolian School

This was a private school founded by Haroutyun Gelibolian. He had been educated in Istanbul, and founded the school in Rodosto, in the Holy King neighborhood, in 1882. The school was attended by Armenian, Jewish, Latin, and Turkish pupils. It was closed down in 1888, and Gelibolian became the principal of the Hovnanian School, located in the same neighborhood. In 1892, he left for Istanbul, then returned to Rodosto a few years later and reopened his private school [26].

Enrollment at this private school was about 50 pupils. Gelibolian was a scholar of the French language, and the school offered instruction mainly in French [27].

The Idadi Public School

This was a public Ottoman school, offering a three-year program of instruction – the last year of primary schooling and the first two years of secondary schooling. Instruction was in Turkish and French. We know that some Armenian families sent their children to this school once they had graduated from their neighborhood Armenians schools. Among these pupils were Hagop Boyadjian and Dikran Baghdigian. The latter was elected to the Ottoman Parliament in 1909 [28].

We also know that Dikran Baghdigian worked as a teacher at this school from 1908 to 1912. At the time, the principal of the school was Srab Abahouni, and Baghdigian held the position of vice-principal [29].

Among the school’s Armenian teachers was Garabed Hampartsoumian (beginning in 1906) [30].

The Armenian Schools of the Town of Chorlu

What we know about the Armenian schools of Chorlu comes to us from a series of articles that appeared in the pages of the Istanbul -based newspaper Puzantyon (Byzantium) in 1901. It is very likely that in later years, particularly after the 1908 restoration of the Ottoman Constitution, the field of Armenian education in Chorlu experienced a period of growth, as it did in other parts of the empire. Unfortunately, we have no sources that attest to this.

The Saint Kevorkian Coeducational Elementary School (Chorlu)

The school had an enrollment of 210 pupils of both sexes. The school building was constructed under the patronage of Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian [31].

In 1901, four teachers of both sexes worked at the school [32].

In 1905, Krikor Yarazlian was the principal of the school. He was a native of Rodosto and had previously worked as a teacher at the city’s Hovnanian School [33]. In later years, Father Kevork Tourian and Father Kegham Yeldezian would serve as principals [34].

Among the teachers who taught at the school were Reverend Daniel (later Father Mesrob, who served in the Galata neighborhood of Istanbul), Hayrigian Effendi, and Father Arisdages Malakian (in the 1890s) [35].

The Armenian Schools of the Cities of Silivri, Gallipoli, and Malgara

We have little information about Armenian schools in these cities.

We know that there was a school in Malgara called the Mamigonian School, located adjacent to the Saint Toros Church [36]. Filor Batmazian (later Tanielian) worked as a teacher at this school until 1915. Among the school’s other teachers were Father Tateos Poryadjian and Sarkis Srents [37]. Ardashes Haroutyunian (1873-1915), who was later to become a celebrated writer and intellectual, was born in Malgara and attended school there [38].

Filor Batmazian (later Tanielian) also worked as a teacher at the Armenian school of Gallipoli from 1920 to 1922 [39].

Adjacent to the Saint Kevork Church of Silivri was the Varvarian School, which had an enrollment of about 90 pupils. The school was said to have been founded by Father Khoren Djamdjian, a graduate of the Hovnanian School of Rodosto. He was sent to Silivri in 1900 to serve as the priest of the Saint Kevork Church. Father Khoren also taught at the school. Among the school’s other teachers was Father Garabed Dishlian. Celebrated author Roupen Sevag (Roupen Chilingirian) attended this school, and later continued his education at the Berberian School of Constantinople [40].

- [1] Sarkis K. Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun 1606-1922[Memory Book of the Armenians of Rodosto 1606-1922], G. Donigian Printing House, Beirut, 1971, page 213.

- [2] Ibid., page 216.

- [3] Ibid., page 217.

- [4] Ibid., page 213.

- [5] Ibid., page 91; “Kavarayin Kronig” [“Provincial Chronicle”], Arevelk, year 12, number 5969, September 3/16, 1905, Istanbul.

- [6] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 221.

- [7] Ibid., page 223.

- [8] Ibid., pages 223-224.

- [9] A. M., “Rodostoyi Hayoutyune” [“The Armenians of Rodosto”], Joghovourti Tsayne, n. 576, August 22/September 4, 1920, year B; and Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev Ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin[The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and Its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915], New York, 1985, page 415.

- [10] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 98, 116; and pages 138-139, 166-167, and 187-189.

- [11] Ibid., page 104.

- [12] Ibid., page 213.

- [13] Ibid., page 216.

- [14] Ibid., page 217.

- [15] Ibid., page 221.

- [16] Ibid., page 222.

- [17] Ibid., page 82, 91, 97, 166, 188, and pages 213-214; and Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pages 417-418.

- [18] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 221.

- [19] Ibid., page 55.

- [20] Ibid., page 104.

- [21] M. H. Kouzo-Kebabian, “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyune, 1852-1902” [“The History of the Church in Rodosto, 1852-1902”], Puragn, year 20, n. 51, December 21, 1902, page 813; and year 21, n. 8, February 22, 1903, pages 157-159.

- [22] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 216.

- [23] M. H. Kouzo-Kebabian, “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyune, 1852-1902,” Puragn, year 21, number 16, April 19, 1903, pages 311-312.

- [24] M. H. Kouzo-Kebabian, “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyune, 1852-1902,” Puragn, year 21, number 8, February 22, 1903, pages 157-159; and year 21, number 16, April 19, 1903, pages 311-312.

- [25] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 214.

- [26] Ibid., page 88.

- [27] Ibid., page 217.

- [28] Ibid., page 93 and page 96.

- [29] Ibid., page 96.

- [30] Ibid., page 98.

- [31] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayere (Irents Antsyals ou Nergan)” [The Armenians of Çorlu (Their Past and Present)], Puzantyon, year 6, number 1561, November 13/26, 1901, Constantinople; “Provincial Chronicle,” Arevelk. Year 12, number 5969, September 3/16, 1905, Constantinople.

- [32] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayere (Irents Antsyals ou Nergan),” Puzantyon, year 6, number 1564, November 1901, Constantinople

- [33] “Provincial Chronicle,” Arevelk. Year 12, number 5969, September 3/16, 1905, Constantinople.

- [34] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 185 and 188.

- [35] Ibid., page 188; Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayere (Irents Antsyals ou Nergan),” Puzantyon, year 6, number 1561, November 13/26, 1901, Constantinople; “Provincial Chronicle,” Arevelk. Year 12, number 5969, September 3/16, 1905, Constantinople.

- [36] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, pages 188-189.

- [37] Ibid., page 91, 139, and pages 188-189; “Provincial Chronicle,” Arevelk, year 22, number 5969, September 3/16, 1905, Constantinople.

- [38] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 418.

- [39] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, page 139.

- [40] Ibid., page 201; Teotig,Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, page 416 and page 419.