Rodosto – Festivals

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 08/07/19 (Last modified 08/07/19) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

Generally, Armenian religious festivals were celebrated in the same manner, and featured the same rituals and ceremonies, throughout the Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, it is always possible to find variations in the customs of specific areas. These variations were what gave these celebrations their diversity and richness of character. Every time we study a new Armenian-populated area of the Empire, we find new traditions and customs, which enrich our knowledge of Armenian holidays and their celebration.

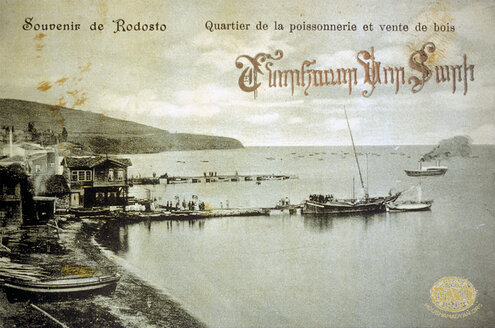

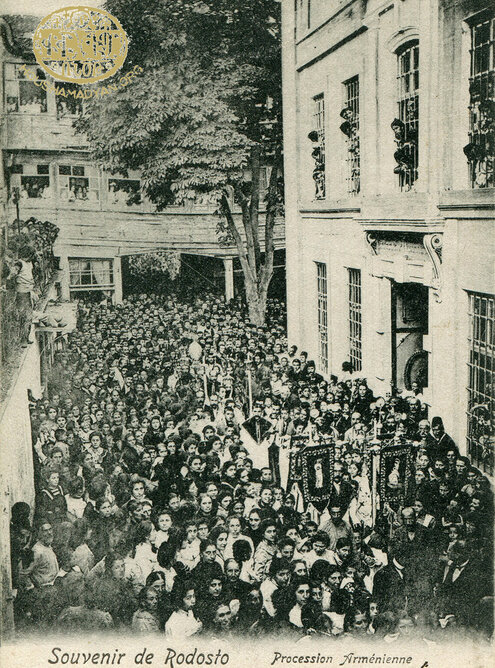

We have relatively few primary sources regarding the celebrations of holidays in the Rodosto area. However, these few sources still give us a glimpse into the area’s unique customs. For example, we know that certain religious traditions had traveled from Gamakh/Kemah and Yerzenga/Erzindjan, and had been preserved on the distant, European shores of Rodosto. We know that many of the Armenians in Rodosto were descendants of Armenians who had immigrated from these areas at the start of the 17th century. These immigrants brought with them the relic of the Holy Nail, built a church in Rodosto to honor this relic, and each year, on the Holiday of Assumption of Mary, organized a religious procession, during which the relic was paraded in the city streets.

New Year’s Eve

In Rodosto, it was customary to prepare a rich dinner feast for New Year’s Eve. The week of December 29 to January 5 was a time of fasting, so the feast would feature the seven Lenten dishes of wheat kolva, boiled beans, lentil dolma, broad bean ezme (paste), fried leeks, tertig, and grape touri.

Before the meal, the adults would drink seven cups of arak. This ritual was called okhde rakhi, which probably meant oukhdi oghi (arak of vows). A copper or silver coin would be baked into the bread eaten by the revelers. Whoever bit into the coin would be blessed with fortune throughout the upcoming year.

After dinner, holiday fruits would be served, and the revelers would feast until dawn.

On New Year’s Day, the children would receive presents.

At dawn, immediately after sunrise, the church sexton and choir would visit the homes and sing:

Nor aravod dzakets aysor

Mez nor dari shnorhavor.

[A new morning has dawned today,

Happy new year to us all!]

Then Armenian simitdjis [bakers of simit, a type of bread] would make the rounds of the city, calling out to customers and singing while selling their simits, which would be carried in two baskets hanging over the sides of their donkeys.

In Rodosto, New Year’s celebrations were not considered a religious occasion, and for that reason, the city’s residents all went to work on New Year’s Day. [1]

Christmas

The Christmas service at church began very early in the morning, and consequently, the parishioners made their way to church in the darkness, carrying lamps. Thereafter, Christmas well-wishes echoed through the city streets.

Lunch on Christmas generally featured khash (pacha). It was also customary to visit relatives and friends on this day. The visitors were usually each household’s menfolk, while the women would remain home and welcome their guests. Visitors were offered sweets and cognac.

The day after Christmas, the firefighters of the Armenian neighborhood, with red veils wrapped around their heads, visited all the homes, collecting donations. Their presence was critical in the neighborhoods of Rodosto, given that homes were built of wood and fires were a constant threat. Generally, every home gave something to the firefighters. The latter would spray the children with rose water as a joke. [2]

1) Rodosto. The Holy King neighborhood. The church procession on the occasion of the holiday of the Assumption of Mary, during which the church’s main relic, the Holy Nail, was displayed to the public. The building visible on the right is probably the Hovnanian School (Source: Grégoire Tafankejian collection, Valence).

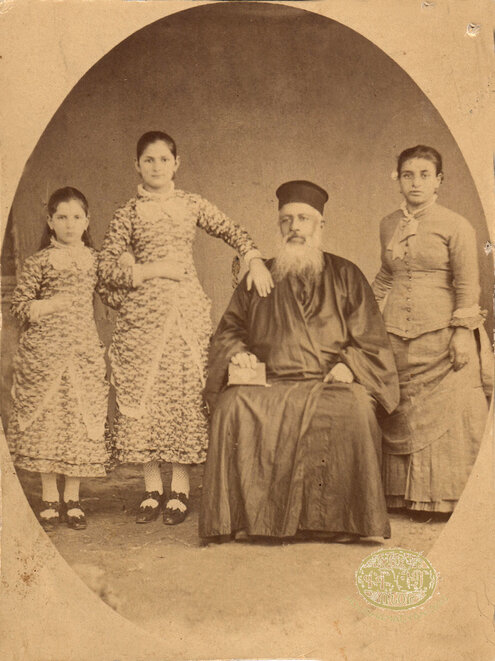

2) Chorlou. An Armenian priest with his family (Source: Yetvart Tovmasian Collection, Istanbul).

Deyarentarach (Candlemas)

In Rodosto, this holiday was known as Derindas. It was celebrated in February, 40 days after Christmas, which coincided with the celebration of the presentation of Christ at the temple. But at its core, the holiday harkened to the pagan past. The people of Rodosto would start bonfires on the city square or at the top of the streets, and would gather around the fires. Some would jump over the flames, chanting “Derin das das, Derin das das”. [3]

Easter

Easter was the most important holiday on the Armenian Christian calendar. All work in the fields would cease on the Thursday before Easter Sunday. The artisans and traders would keep their shops open, but they and their employees would invariably attend church services on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday.

Maundy Thursday was also when the people dyed eggs for Easter. The dye was generally obtained from onion skins.

Among the religious ceremonies staged on Good Friday was the reenactment of Christ’s burial. This took place simultaneously both at the Holy King and Holy Cross churches. There were always plenty of people wishing to carry Christ’s coffin. Generally, those who donated the most money to each church were selected. These pallbearers wore silver-lined shirts while carrying the coffin. The funeral procession would leave the church from the Epistle side, would circle round the courtyard, then re-enter the church from the Gospel side. As the procession passed them, the parishioners would kneel before it, some hoping that this act would cure their various illnesses, others hoping that it would ward of all illness.

Friday and Saturday were also dedicated to the preparation of cheoreg in the Armenian neighborhoods. The aroma of pastries filled the streets all day.

Easter Day was a day of jubilation for the people. Special areas were designated in both the Holy King and Holy Cross neighborhoods of the town of Rodosto, where people gathered and celebrated Easter with feasts. These areas would be decorated specially for the occasion, and sellers of many types of food would be making their rounds. Noisy and chaotic celebrations were common on this day. The air would be filled with whistles and occasional gunshots, all marks of celebration. [4]

Feast of the Ascension

This holiday was celebrated on Thursday, 40 days after Easter. The Armenians of Malgara celebrated it with a special pilgrimage. They would visit the “Priest Movgim” natural spring/holy site (ayazma), located near the city. [5]

Vartavar

In Rodosto, this holiday was known as Vartevor. On the Christian calendar, it coincides with the Feast of Transfiguration of Christ. It was celebrated 98 days after Easter. On this day, it was customary for people to drench each other with water, which is evidence of the holiday’s pagan origins. [6]

Feast Day of Mary

This holiday is also known as the Assumption of Mary. It had special significance in Rodosto, as it was also the feast day of the Holy King Church of the town of Rodosto. On this holiday, in the middle of August each year, thousands of pilgrims would descend on Rodosto. Pilgrims from Malgara would arrive on the Wednesday before the holiday, pilgrims from Chorlou on the Thursday, pilgrims from the Asian side on Friday and Saturday. Finally, on Sunday, natives of Rodosto living in Istanbul would enter the city.

A monastery, built of wood and containing 80 rooms, was located adjacent to the Holy King Church. The entire building would be dedicated to housing the pilgrims. Many others stayed with relatives in Rodosto.

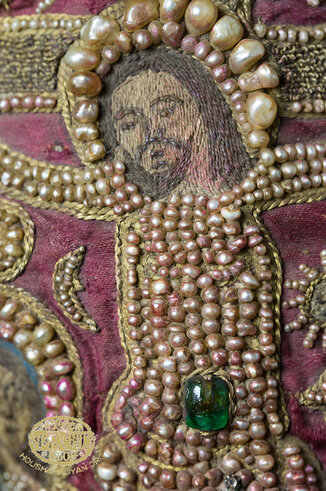

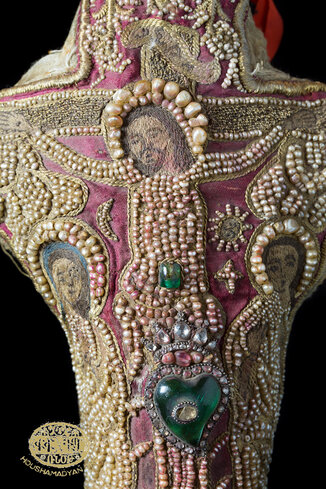

The church ceremonies to mark the holiday would begin on Saturday evening. The highlight of the day was the presentation of the relic of the Holy Nail to the throngs of worshippers. This was the most important relic owned by the Holy King Church. According to tradition, it was the nail that held the sign that read “Jesus, King of the Jews” on Christ’s cross. The church’s name, Holy King, was a reference to this relic.

Sarkis Pachandjian provides the following description of the Holy Nail – “The nail is borne on a special four-winged metallic cross, which bears a depiction of the crucified Christ in pearls and diamonds. At the center of the cross is a large, spear-shaped emerald adorned with gems. The nail is kept in a wooden box, at the top of which is a depiction of the Lord, below it a depiction of the crucifix, and images of the four evangelists at the corners”. [7]

It was said that the Holy Nail had been brought to the church by Krikor Taranaghtsi from one of the monasteries of the Gamakh/Kemah region, when the Armenian population of that area was forced to abandon its native land in the early 17th century due to the endless wars between the Ottomans and the Persian Safavids, as well as the violence unleashed by the Djelali rebellions. Many of the Armenian refugees from Gamakh had settled down in the Rodosto area. Another story was told of an Armenian from Gamakh living in Byzantium, who had received the relic from the Byzantine emperor, as a reward for having healed his dying daughter. The Holy Nail was then taken to Gamakh and kept in the area’s monasteries and brought to Rodosto in 1606 by refugees. In 1922, when the Armenians of Rodosto left the city for good, they took the Holy Nail with them to Bulgaria. At present, the relic is kept at the Saint Kevork Armenian Church of Plovdiv. [8]

In Rodosto, on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, the Holy Nail was displayed to the public in a special procession, which was led by specially designated honorary patrons. The procession would leave the church and make a round of its courtyard.

Sunday was the actual day of the Feast of the Assumption. A special service would be held before noon, and the Holy Nail would be taken out of the church again. But this time, the procession would leave the church courtyard and make a round of the area’s streets. Large crowds would attend this ceremony, and police officers would attend to keep the peace.

On this holiday, it was customary for coffee houses and wine houses in the Armenian neighborhood to be decorated with branches with plenty of green leaves, as well as colorful paper. A similar celebratory mood prevailed in the neighborhood of the Holy King Church, which would also be decorated for the occasion. Long ribbons would be stretched between homes on either side of the street, so many that entire street would be covered with colorful paper and cloth.

The celebrations of the Assumption of Mary spanned two days, and throughout this time, feasts were organized in the environs of the Holy King Church.

In 1913, the 1,500th anniversary of the discovery of the Armenian alphabet was celebrated alongside the Assumption of Mary, which added to the celebratory mood of the day. In the early 1920s, marches of scouts and athletes were also held to mark this holiday. [9]

Feast of Saint Kevork

The Armenians of Rodosto also called this holiday Khderellez.

The holiday was celebrated on the Saturday falling between September 25 and October 1. It was also the day of pilgrimage to the Saint Kevork Church of Chorlou. Consequently, the holiday had special significance for the local Armenian population. Every year, pilgrims from both the city and the surrounding area gathered inside the church and its courtyard. The pilgrims from the city came in carriages and stayed for the whole week. To accommodate the yearly crowd, a building with 30 rooms was built behind the church. [10]

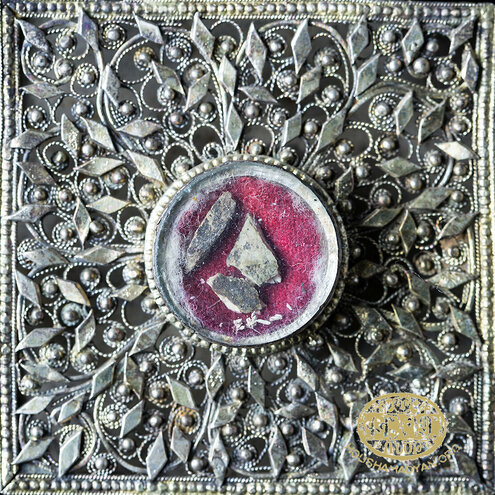

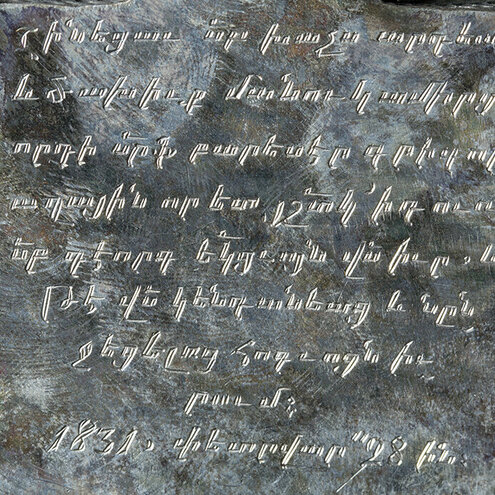

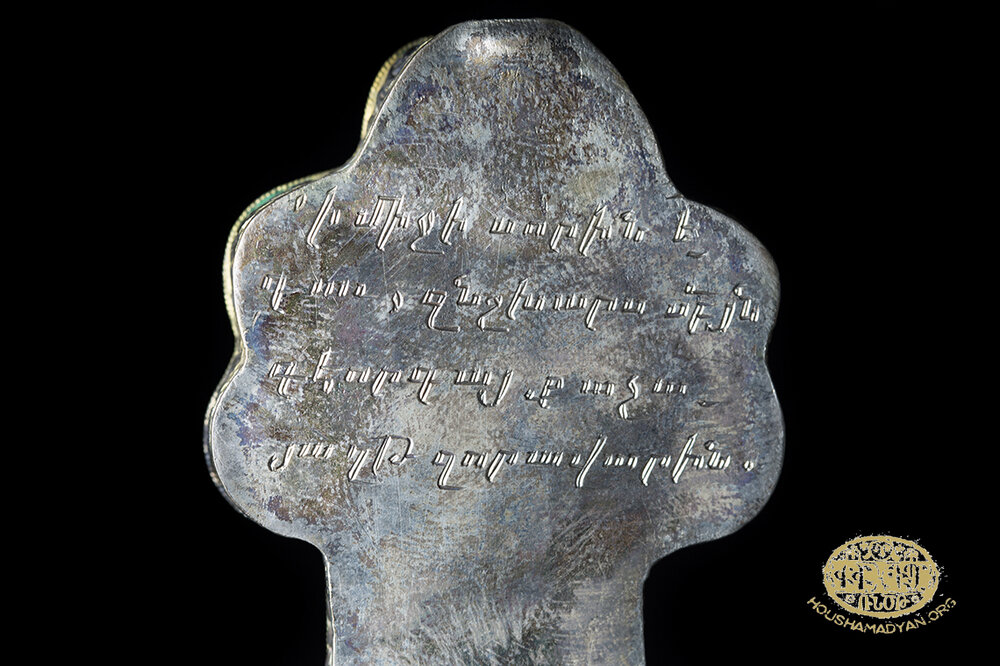

A silver cross. The back of the cross indicates that it was a gift to the Saint Kevork (George) Church by Manoug Gamirtsi (son of Krikor agha), and was presented to the church on February 28, 1831. This Saint Kevork Church was presumably the church of that same name in Chorlou. It is also noted that the cross bears relics of Saint George, the “Unconquerable Warrior.” It is currently kept at the Saint Kevork Church of Plovdiv. Photographed by Raffi Youredjian.

Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross

This holiday was also the feast day of Rodosto’s Holy Cross Church. It was celebrated on the Sunday falling between September 11 and September 17. The church would be filled with a huge crowd of believers, and animals would be offered as sacrifices, including lambs, sheep, and calves. These animals were kept in the best of conditions all year by their owners, and were fattened specially for this occasion. On the day of the feast, their owners would bring and offer them to the church. Others would donate large sums of money or large quantities of pita bread.

Special ditches were dug behind the Holy Cross Church, where the sacrificed animals would be inspected beginning early on Sunday morning. The name of the offerors, and the type of animal they offered, were recorded in the church registry.

In the afternoon, the work of slaughtering the offerings and cooking their meat would begin. The meat would be cooked in large vats, and the stock would be distributed to the people, who would later make soup and pilaf with it.

The Holiday of Merelots (Remembrance of the Dead) was marked on the following day. A service was held at the church, and the sacrificial offerings blessed. The entire Armenian population of the city, as well as local Turks and Greeks, would gather, seeking a morsel of the sacrificial offerings. [11]

- [1] Sarkis C. Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun 1606-1922 [Memory Book of Rodosto Armenians 1606-1922], G. Donigian Printing House, Beirut, 1971, p. 238.

- [2] Ibid, p. 239.

- [3] Ibid.

- [4] Ibid, p. 240.

- [5] Ibid, p. 199.

- [6] Ibid, pp. 240-241.

- [7] Ibid, p. 229.

- [8] Ibid, pp. 230-231.

- [9] Ibid, pp. 224, 229-230, 241.

- [10] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayere: Irents Antsyaln ou Nergan” [The Armenians of Chorlou: Their past and present], Puzantyon, sixth year, n. 1554, November 5/18, 1901, Constantinople; Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun, p. 200.

- [11] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun, pp. 242-243.