Erzindjan/Erzincan/Yerzenga – Trades and Commerce

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 30/04/20 (Last modified 30/04/20) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

After a short journey, he reached Kantaria charshi, the grocery market, which separated the Armenian and Turkish neighborhoods of Yerzenga.

“The leblebi [a snack made from roasted chickpeas] sellers would sit right over here,” thought the old man, but the thought escaped his lips. “Were there three of them, or four? Each would sing the praises of his leblebi – how delicious it was, how it melted in your mouth, how it wouldn’t harden, how lightly sweetened it was…”

The memory was now as clear in the old man’s mind as the light from the rising sun. Every day, at noon, he would take food to his father, who had a bakery on the church square. He would leave the house carrying a package bundled in variegated handkerchiefs, containing, in addition to the containers of liquid food, onions and cheese, without which his father could never eat a meal. He would make his way down the tree-lined street where Sarkis Efendi lived, would drink water from the frigid spring that flowed near the Holy Savior Church, and then head down the winding, narrow road off to the left. He would throw a stone at the chained dog that would always be there, and then, with its rabid growls ringing in his ears, he would sprint to the door of the bakery. His father, exhausted from the day’s work, would eat peacefully, sitting on a stool, constantly taking big gulps of cold water from a jug. He would gaze at his father and dream of how when he got older, he, too, would let his mustache and beard grow and become a baker. When he finished eating, Garabed Agha would sometimes give him a copper coin, lift him up, kiss his forehead, eyes, and nose, then release him like a dove: “Fly away and do as your heart desires!” He would run back into the market, his young spirit lifted by the delectable perfumes, vivid colors, and energetic and cheerful voices that called to him. He would approach the Greek who wore the dark glasses and the long beard. “Buy our leblebi,” would say the Armenian hawkers, “what a betrayal of your own kind!”

Still, he would always buy the leblebi from the Greek, because (and here, a deep groan escaped from deep inside the old man’s chest), his leblebi was magical. It was as if it weren’t leblebi at all, but something else that you had to carefully place upon your tongue, close your eyes, and try to relish, in all its perfumed glory, as long as possible.

Excerpt from Norayr Atalian’s story Gabouyd Yerzenga [Blue Yerzenga] (Norayr Atalian, Gabouyd Yerzenga, Yerevan, 1985, pp. 141-142).

A general overview of the history of trades and commerce in Erzindjan

Erzindjan was located at the junction of the roads that led from south to north, through Armenia, to the ports of the Black Sea; and the trading routes linking east to west. Thanks to its critical location, the city has been a center of trade and commerce since the Middle Ages, and an important stop on the Silk Road. Many of the city’s products enjoyed a great reputation and great demand in eastern markets [1].

The famous 13th century explorer Marco Polo, who visited Erzindjan in the 1270s, noted that the city produced the best woven cotton in the world, called buckram [2].

The Arab explorer Ibn Battuta, who visited Erzindjan in the 1330s, described it as a large and prosperous city with a large Armenian population, famed for its well-ordered markets. He also noted that the city produced beautiful fabrics which were known by its own name, while the copper mined from the outskirts of the city was used to make various plates and other objects, namely copper candelabras (“payouses”) [3].

In subsequent years, Armenia became a battlefield between the Turkish Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu dynasties. After its capture by the Ottoman Turks, Erzindjan lost its former status as a hub of international trade, but remained an important commercial link between the Ottoman and Persinan empires [4].

Another reason for the decline in the amount of trade flowing through the city was the fact that between the 17th and the second half of the 19th century, the central Ottoman authorities had only nominal jurisdiction over the area. As a result, the trade routes were not safe, and the merchants traveling them, even whole caravans, were subject to attacks by marauding Kurds, who would pitch their camps in the Erzindjan valley with their cattle, especially in the summer months [5].

The situation changed after the years 1853-1856, and even more so after the years 1877-1878, after the Russo-Turkish War, when Erzindjan was reinforced with a military detachment deployed by the central Ottoman authorities. In 1885, the decision was made to permanently establish the headquarters of the Fourth Ottoman Army in the city, with jurisdiction over the provinces of Erzurum (Garin), Van, Diyarbakir (Dikranagerd), Sivas (Sepasdia), and Trabzon [6]. This resulted in the revival of trade and commerce in Erzindjan, thanks to increased security, improved roads, and an increase in local demand for merchandise.

Erzindjan was connected, via busy roads, to Trabzon, Erzurum, Sivas, and Harput/Kharpert, in effect acting as a hub of communication between these cities [7]. “After the arrival of the army in Erzindjan, highways were built, roads opened, and a certain sense of security prevailed. Parallel to all this, the economy also began to grow in leaps and bounds,” attests K. Surmenian [8].

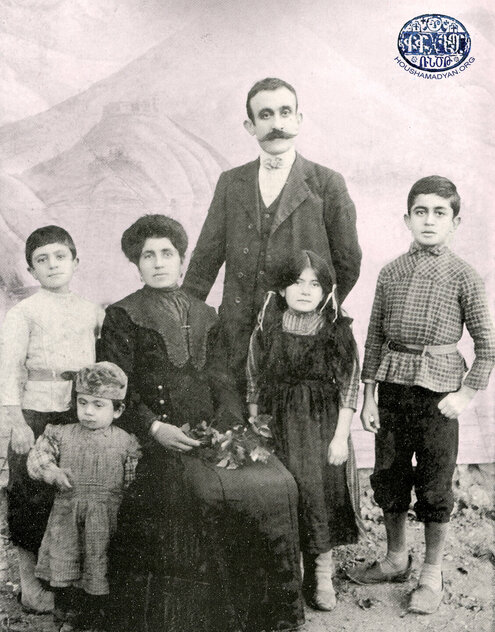

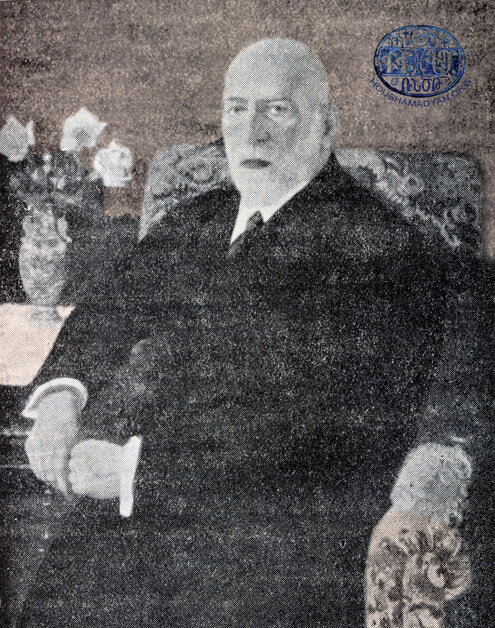

Although Armenians represented only about a third of the population of the city and district of Erzindjan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they owned a disproportionately large number of business and commercial enterprises [9]. According to one source, on the eve of the Armenian Genocide, 1,500 of the city’s 2,500 stores and market stalls were owned by Armenians [10]. The city was home to 425 retail establishments, 70 merchants, 124 fruit sellers, and 45 grocers. The number of craftsmen was 905 [11].

The trading houses owned by Erzindjan Armenians had established relationships with counterparts in Erzurum, Constantinople, Izmir, Trabzon, and other commercial centers, and had their agents and representatives in those cities. Some even personally traveled abroad, to European cities, to study the markets there and to establish relationships [12]. In their turn, traders and workers from other areas (Agn, Arapgir, Harput, Gurun/Gurin, Kumoushkhane, etc.) practiced their trades in Erzindjan [13].

In the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the principal industries in the city of Erzindjan were the Manisa cotton industry, the leather industry, and coppersmithing. According to French researcher Vital Cuinet, in the 1880s, more than 15,000 kilograms of copper ore was imported from Europe to Erzindjan, via Trabzon. The ore was then used to produce various kitchen utensils and receptables, intended for both the local and export markets. Copperwork produced in Erzindjan received praise after being exhibited in the world fairs of Paris (1867), Vienna (1873), and Philadelphia (1876). V. Cuinet notes that the Armenian craftsmen of Erzindjan were also experts at crafting small decorations from silver and steel [14].

At around the same time, large Armenian manufacturing/trading houses began appearing in Erzindjan, many specializing in the manufacture and sale of local Manisa cotton. Among the most notable of these trading houses were the Der-Sdepanians, the Lepian brothers (Haroutyun and Krikor), and the Vartabedians. Their products were sold not only locally, but were also exported to other parts of the country (Erzurum, Pasen/Pasinler, Keghi, Bayburt/Papert, Kumoushkhane, etc.) [15]. The Lepian brothers owned several cotton plants with 15 dolabs (devices used in the production of Manisa cotton) and 500 tezkahs (workbenches) each. The Lepian brothers received their raw cotton thread from the city of Manchester in Great Britain [16].

The renowned Armenian merchants of the city (Tanielian, the Luledjian brothers, Kapriel Ghazarosian, Chaldjian, and the Papazians) also supplied the local detachments of the Ottoman armies and police with food [17].

The wealthy merchants of Erzindjan played an important role in the city’s community and educational/cultural life, both directly and indirectly as members of neighborhood councils, the Prelacy’s political and religious councils, and Armenian economic and educational councils. They also sponsored neighborhood schools, made large donations to support the construction and renovation of churches and monasteries, and provided financial assistance to the Prelacy’s various programs that helped orphans and other needy.

The Hamidian massacres were a terrible blow to the economy of Erzindjan’s Armenian population. On October 9/21, 1895, a mob of armed Turks and Kurds descended on the central market of the city, indiscriminately killing any Armenian they could find, and destroying and razing to the ground their shops and market stalls. In this outburst of mass violence that lasted several hours, hundreds of Armenians were killed and injured, and virtually all Armenian businesses were destroyed. The Turkish policemen and soldiers present at the scene made absolutely no attempt to stop the violence [18].

The terrified and stunned Armenian craftsmen and merchants of the city, fearing more violence, did not return to the market or reopen their stores for months. They were replaced by local Turkish merchants, some of whom unabashedly began selling the merchandise that they had stolen from their Armenian colleagues [19].

Economic life in Erzindjan experienced a period of rebirth after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the reinstatement of the Ottoman Constitution. New commercial establishments and trading houses were founded, and local production and commercial activity increased. However, the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and the Armenian Genocide brought all further economic progress to a halt.

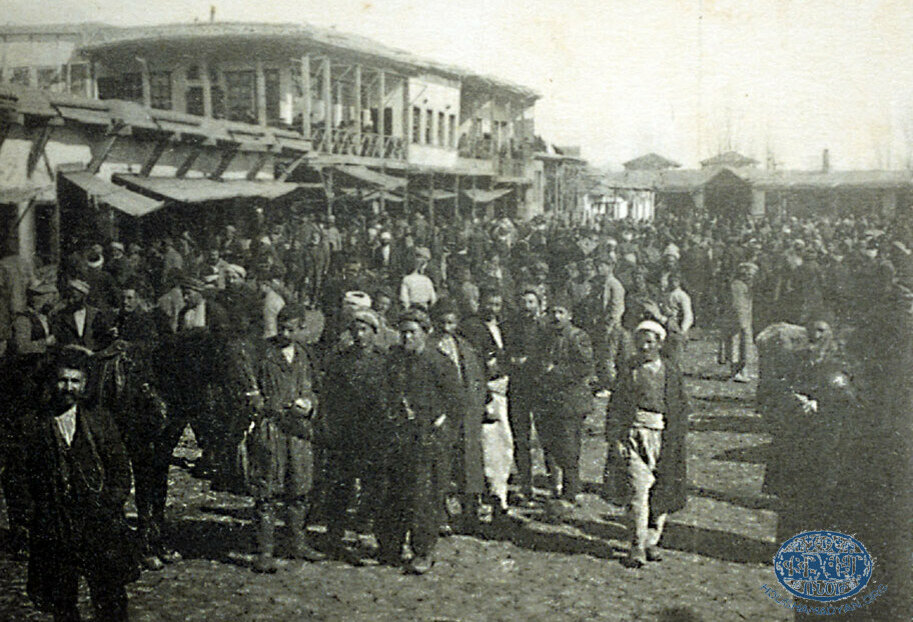

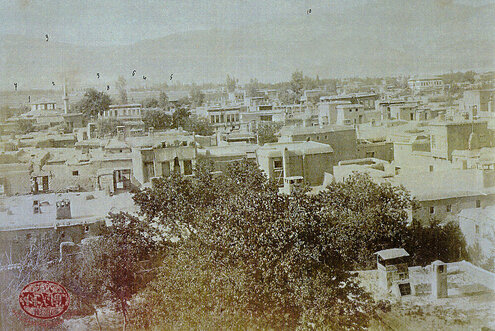

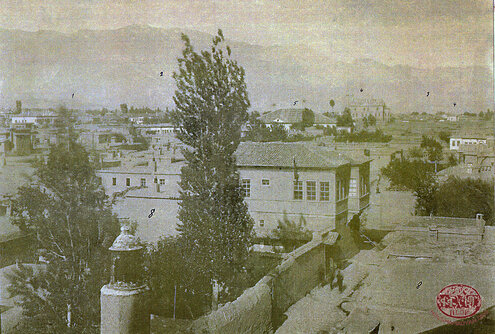

The market of Erzindjan

The vast central market of Erzindjan was located in the center of the city, separating the Armenian and Turkish neighborhoods. It was divided into different sections, according to different occupations and branches of trade. Its main sub-markets were:

1. Bezestan or Bezazia Çarşısı (charshusu): this part of the market was dedicated to the sale of local and European textiles of all types; printed textiles (calico or pasma); other fabrics; fine silk embroideries from Damascus, Aleppo, and Harput; yazmas; fezes; kerchiefs; belts; towels, dimi (a type of fabric); Manisa cotton, etc.

2. Touafiye Çarşısı: this was the part of the market where all kinds of small household items were sold, including trinkets, porcelain, glassware, stationery, etc. There were also stalls selling rugs and fabrics.

3. Kantaria Çarşısı: this was the part of the market with the greatest concentration of grocers (selling flour, tea, sugar, coffee, soap, rice, olive oil, kerosene, etc.) There were also stores that sold household items made of glass, iron, copper, and other metals; as well as seamstresses’ stalls.

The stores and stalls in these three sections of the market were owned almost exclusively by Armenians.

Armenian merchants also had control of the lumber industry in Erzindjan (they were called keresdedjis). Armenians owned almost all of Erzindjan’s wineries, and dominated the trade in wine and other alcoholic beverages. Armenians from Kemakh controlled the trade in coffee.

The stores and stalls of the market were slightly elevated from the ground, with an open front, without doors and windows. The entrance and exit consisted of double wooden shutters. The bottom shutter, called the peke, also served as a floor covering and a bench. The shopkeepers would sit on a straw mat or cushion placed on the peke and attend to their customers.

The area separating the shops from the streets would be covered by thick waterproof material to protect it from the rain and snow.

The stalls of the best coppersmiths (or ghazandjelars) of Erzindjan were concentrated around the small square called Tahtaghala, near the Kourshounlou/Kurşunlu Mosque. There were several large smelters and foundries there, where old or scrap copper was melted and molded, transformed into ingot, and resold to smiths, who used it to make new receptacles, plates, or other utensils. “Anyone entering the square would be deafened by the sound of the striking hammers. One would think he was at a circus,” writes K. Surmenian. “To temper the hot copper, six-seven smiths would gather around a large anvil, and upon the signal from the master, begin striking the ingot with their hammers in such perfect harmony that one would think only one man was at work” [20].

Not too far from the coppersmiths were the small markets of Erzindjan’s jewelers, or ghoyoumdjilars, who were almost exclusively Armenian; the merchants selling cotton and wool products (blankets, pillows, bedsheets, cushions for furniture, window coverings, curtains, etc.), also called pamoukdjelars or yorghandjelars (a mixture of Armenian and Turkish); and the makers of leather footwear (the paboudjdjilers or yemenidjilers) [21].

Aside from its central market and sub-markets, Erzindjan was also home to several relatively large commercial establishments/inns/stores, which were called khans.

The city’s oldest and largest commercial khan was Tashkhan. It was located in the south of the city’s market district, in a sturdy building built of stone. It had two giant metal gates, one of which opened to the west, while the other opened to the east, facing an area that was known as the “wheat square.” The western gate also bore an inscription stating that Tashkhan was founded in year 953 of the Hijra (1546 CE), during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

Tashkhan had a large courtyard, its floor paved with polished stones. The courtyard featured a fountain in its center and was lined with rooms reserved for shopkeepers and merchants. The second floor served as a storehouse and granary.

For long years, Tashkhan had served as haven for Armenian migrant merchants from Arapgir, who would visit Erzindjan to sell embroideries, cotton products, calico, soap, and other wares from Arapgir, Harput, Aleppo, Diyarbakir, and other southern centers of trade.

The city’s second khan, called Salou Khan, was located in the north of the market district. It was built of bricks, had two floors, and a wooden roof. It had a large courtyard, with an unimpressive fountain in the corner. Thanks to its location in the most crowded section of the market, the khan was always full of Armenian merchants, and functioned as a unique exchange/stock market [22].

The more recently built Papaz Oghlu Khan was considered to be Erzindjan’s most handsome commercial structure, and was located near the central market, in-between the Olou Mosque and Salou Khan. It was built by a consortium of some of the wealthiest men in Erzindjan, including the Papazian family, who also gave it its name. It had only one gate that led into a unique courtyard with a beautiful fountain in its center, lined with well-lighted and well-kept rooms. Compared to the others, this khan was better-maintained, cleaner, and better-run [23].

The principal occupations and professions among Erzindjan Armenians

Manisa cotton-weaving and related products

One of the more widely practiced trades among Erzindjan Armenians was the production of Manisa cotton. Manisa cotton was a woven fabric, either with narrow or wide stripes or without stripes, made with spun thread and used to make various types of clothing.

Manisa cotton was made using the following procedure. The master would create a pattern according to his preferences, then prepare the thread of the Manisa, roll it into an oval ball, the mshdout, and give the mshdout to the weaver. The weaver would use a loom to cut up the thread and prepare the Manisa fabric, which would then be handed to the manufacturing plant or the client. Each piece of Manisa fabric, called a top, would measure 8-10 arshins (6-7 meters) in length and about one arshin (0.70 meters) in width. Each tailor would use about one top of Manisa per day.

According to one source, approximately 2,000 Armenian families [25] from the city of Erzindjan and surrounding villages were engaged in the Manisa cotton industry in the mid-1880s. K. Surmenian writes: “It can be said that about half of the Armenian population of Erzindjan made its living through this trade, because by the time the cotton thread became Manisa, it was worked on by about ten pairs of hands. Aside from selling it, someone had to wet it, dye it, fill the arech, make the mshdout, and weave the fabric. This required a large workforce” [26].

In Erzindjan, the Manisa cotton industry was the exclusive preserve of Armenians. As we have already mentioned, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, large factories producing Manisa, and large stores selling it, operated in Erzindjan. They were owned by the Lepian brothers, the Vartabedian brothers, the Der-Stepanian brothers, Vartan Ehramdjian (the Ehramdjian family also specialized in the production of a type of white fabric consisting of fine, thin threads of wool, which was used by women to saw ehrams (sheets)), Ghazar Peg-Norsigian, and others [27].

Types of Manisa included sergi (colorful, with large stripes, of simple design or with floral patterns, used to sew bedsheets, pillowcases, sofa sheets, and curtains) and dimi (colorful, with narrow stripes, or of simple appearance and without stripes, delicate, and used to sew summer clothing).

Another type of Manisa cotton produced by Erzindjan Armenians was khavloudji, a thick fabric used to make hand wipes, floor rags, aprons (ghenchags), etc.

Erzindjan Armenians also made yazma (the craft was called yazmadjiyoutyun), a fabric with colorful imprinted motifs, mainly used to make headwear for women. To imprint the charms onto the fabric, craftsmen used wooden boards, upon which “skilled artists … Would draw and then engrave with a sculptor’s steel stiletto (ghalem) images of nature, bouquets of flowers, floral patterns, butterflies, and birds” [28].

The same method was used to imprint images into chit, another type of locally produced thick fabric, used to make bedsheets, pillowcases, tablecloths, and curtains.

Among the masters of the art of yazmadjiyoutyun were Seyisian, Chirichgerian, and the Dilberian brothers.

The number of families engaged in Chitchiyoutyun was not large. It consisted of five-six households who shared the surname Chitchian [29].

A common Turkish adage from this era attests to the reputation that Erzindjan Manisa cotton and cotton products enjoyed across the Ottoman Empire: “Erzincyanen bezi, Kemakhen touzou” [“Behez (a delicate fabric made of thin threads from Erzindjan, salt from Kemakh”] [30].

Dyeing

The dyeing industry of Erzindjan was concentrated in the hands of a few large dyeing plants belonging to Armenians, where they performed the dyeing of wool, embroideries, and fabric. The only available dyes were blue and indigo. The dyeing plant owned by the Tanielian brothers was particularly well-known.

The dyers of Erzindjan had assumed the custodianship of the Saint Giragos Monastery [31].

Coppersmithing

After the trade in Manisa cotton, coppersmithing was the second most traditional and prevalent profession among Erzindjan Armenians. These coppersmiths produced kitchen utensils, various types of containers and receptacles, frying pans, pots, water containers, oil saucers, trays, pitchers, tubs, skillets, and plates of all types.

Two branches of coppersmithing were practiced in Erzindjan. One was ghazandjiyoutyun, which implied a specialization in the making of larger and sturdier copper products; and the other was sanakordzoutyun, or the specialization in smaller and finer objects (trays, plates, saucers, various types of cups, tea saucers, etc.) The expert sanakordz masters also adorned their products with various patterns, images of flowers, and other motifs. After being engraved, the product was polished, until the red copper began gleaming like white silver. The copperware of Erzindjan was highly prized in the Ottoman Empire, rivaling the work of Tokat and Constantinople [32].

Notably, the coppersmiths of Erzindjan were the custodians of the Saint Kevork Monastery of Yergan, and financed its renovation and refurbishment. In exchange, they had the privilege of spending the summer months in the monastery, alongside their families [33].

Tinning

Alongside and parallel to coppersmithing, tinning (ghaladjiyoutyun, glayekordzoutyun) was the craft of lining the interior of copper vessels with tin, in order to stave off rust and oxidation. Tinning was a simple and common occupation, requiring no special skills or expertise. The tinners of Erzindjan were exclusively Armenian. Some practiced the craft as itinerants, traveling the countryside in the summers and autumns. In exchange for their services, they sometimes received money, but were more often paid in food [34].

Pottery

The large pottery workshops (proudkhanes) of the Armenian potters of Erzindjan were located at a distance 1.5-2 kilometers outside of the city.

These workshops used the clay brought from the Euphrates River to make various vessels and containers, including gdjoudjes-pghoughs (large jars used for aging cheese or pickles), dzaps (deep-bowled gdjoudjes), other types of gdjoudjes, tashkhourans (wide and shallow tubs), water containers, small and large pitchers, larger jugs (for brandy, wine, and other liquids), water pipes, bricks, baked bricks used for walls and as tiles, etc. The containers made to store oil, cheese, and other fresh food were lined with litharge (lead oxide), in order to ensure that they were air-tight and to better preserve the stored items.

Over the years, the pottery workshops of Erzindjan expanded, and their processes were refined. Their owners obtained large kilns in which hundreds of clay products could be baked.

There were also many potters, especially those who focused on the production of gdjoudjes, in the Armenian villages outside the city of Erzindjan, especially Gharakilise.

Customarily, families in Erzindjan who chose pottery as a profession adopted the surname Proudian [35].

Tailors

The Armenian tailors of Erzindjan specialized in the making and alterations of delicate, European-style summer and winter attire. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, among the renowned Armenian tailors of Erzindjan were Nshan Bouloudian (nicknamed “Altoun Makas,” or “Golden Scissors”), Hagop Kouyoumdjian, the Sousigian brothers, Nshan Chitdjian, Avedis Terseklian, Tersekli Haroutyun, and others. The larger tailoring establishments also sold a variety of European textiles and cotton fabrics.

Several Armenian seamstresses also practiced in Erzindjan. They had their workshops in their homes, and specialized in women’s clothing, especially wedding dresses. They counted many of the city’s wealthy and well-known Turkish ladies as their clients [36].

Cobblery

The Armenian cobblers of Erzindjan specialized in the manufacturing of finer shoes (boots or djizmes [37]), potins, half-boots (skarpins), galoshes (potin kaloshes), etc. Among the renowned Armenian cobblers of the city were Krapos Santigian, Yeghia Der Tateosian, Arshag Surmenian, Haroutyun Ipegian, and Avedis Sarafian [38].

Jewelry

Almost all the jewelers of Erzindjan were Armenian, and they enjoyed a reputation as experts in the crafting of gold and silver ornaments (earrings, rings, bracelets, watch chains, watch lids, cigar and cigarette cases, etc.)

There were also master jewelers in Erzindjan who specialized in the making of silver hilts and handles for weapons (knives, swords, daggers, pistols, canes, whips, etc.) The Armenian jewelers of Erzindjan were experts in the application of savat, a black dye used for decoration, to silver.

Turkish pashas and high-ranking officials commissioned Armenian jewelers in Erzindjan to make the jewels they presented to the women in their harems, as well as those they presented to their superiors in Constantinople.

Among the well-known jewelers of Erzindjan were Nshan Kouyoumdjian, the Kouyoumdjian brothers, Avedis Eskidjian, and the Eskidjian brothers [39].

Watchmaking

In Erzindjan, watchmaking was another trade dominated by the local Armenians. Watchmakers mostly engaged in the repairing of watches, as well as the buying and selling of new and old watches. In order to keep the number of watchmakers low, and thus to ensure a steady income, Erzindjan’s watchmakers had pledged not to take on any apprentices from outside of their own families. However, the situation changed in the 1900s when several Armenian master watchmakers from Agn settled down in Erzindjan and refused to take the same pledge. They began accepting local apprentices, thus popularizing the profession.

Two of the city’s renowned Armenian watchmakers were Babig (Babo) Jamakordzian and Avedis Saatdji Hadji Mikayelian [40].

Blacksmithing

Blacksmiths in Erzindjan produced small and large knives, tongs, pincers, penknives, borers, etc. Most blacksmiths in Erzindjan were Turkish, but there were also several Armenian master blacksmiths who produced elegant metallic knives, cradles, simple beds, pails, braziers, window screens, locks, etc. [41].

Some Armenian blacksmiths in Erzindjan specialized in the repair of sewing machines, chariots, and water-pumping devices.

A young Armenian blacksmith from Erzindjan, Avedis Tasligian, gained fame among his peers when, after studying a bicycle brought from the United States, he built his own prototype in 1900. “Though the task was difficult and challenging, the master craftsman finally succeeded thanks to his obstinate determination. The bicycle was finally built, identical to the original, stunning the skeptics,” wrote one of the Western Armenian newspapers at the time [42].

The following year, in 1901, the master craftsman built yet another bicycle, correcting some of the shortcomings of his original creation, which had become apparent after it was put to use. “Mr. Avedis, noticing certain flaws in the bicycle he had built, which were the result of his inexperience, built another bicycle this year and revealed it to the public. The new device is an improved and refined version of the first, although at first glance one cannot tell the two apart,” wrote the same publication [43].

Smelting (bronzesmithing, deokmedjiyoutyun)

To make bronze, smiths would melt copper and tin in forges, then pour the molten mixture into gypsum molds. Once the metal solidified, it would take the shape of the mold, and would then be polished and filed to obtain its final form.

Bronze was used to make candelabras, statuettes, censers, mortars (for crushing or grinding garlic, walnuts, sugar, and other foods) and pestles, various types of plates, fez frames, water jugs, etc.

Because bronze, unlike iron, was not pliable and malleable, bronzesmithing required great care and expertise. For that reason, there were never more than five or six bronzesmiths in Erzindjan at any given time, all of them Armenian.

Among the well-known bronzesmiths of Erzindjan was Khachig Kouyoumdjian [44].

Tinworking and Sobachiyoutyun

Tinworking and sobachiyoutyun were related crafts. Tinworkers mostly made water, milk, and oil receptacles, lamps, funnels, watering cans, trashcans, ashtrays, etc. Sobachis mostly made braziers, tongs, fire grates, and ashtrays. Tinworkers also made other tin items. In Erzindjan, these professions, too, were the exclusive preserves of Armenians [45].

Furniture-making

Furniture-making was a relatively thriving and developed occupation in Erzindjan. The city’s furniture makers, most of whom were Armenian, built household furniture of various types using local lumber, as well as wood imported from the north, particularly from the forests of Lazistan (including pine, fir, walnut, cedar, hazelnut, ebony, etc.) [46].

Carpentry

Carpenters in Erzindjan mostly worked in the construction industry, preparing the wooden components of buildings. The Armenian residents of the village of Mtni, in the vicinity of the city of Erzindjan, had a particular reputation as expert carpenters [47].

Stonecutting (Tashdji)

Stonecutters in Erzindjan were engaged in cutting, polishing, and transporting stonework. They also produced tombstones, grave memorials, crypts, monuments, memorial statues, wellsprings, pools, stone steps, mills, watermills, etc.

In Erzindjan, stonecutters were customarily Greek or Armenian. They built all of Erzindjan’s stone landmarks, including public buildings, barracks, churches, mosques, public baths, bridges, and the stone houses of the wealthy [48].

Bread-baking

The market of Erzindjan included more than 20 bakeries, and there were a few more in the city’s various neighborhoods. Most of the city’s bakers were Armenian. Their main consumers were the non-Erzindjan-native merchants and workers of the city’s market, foreign visitors, and the city’s inns and restaurants.

The locals would usually eat the bread that they baked at home. The woman of each household would usually bake bread every one to two weeks, using the tonir dug at home. For this reason, eating bread from bakeries was considered an embarrassing sign of poverty in Erzindjan, and even the Armenian workers and merchants who spent their workdays in the market brought their own food from home [49].

- [1] E. M. Paghtasarian, “The Armenian Rulers of Yerzenga, 13th-15th Centuries,” Lraper Hasaragagan Kidoutyunneri [Newsletter of Social Sciences], 1970, n. 2, page 36.

- [2] The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, translated and edited, with notes, by Colonel Sir Henry Yule, London, J. Murray, 1903, page 45 (available online at https://archive.org/details/bookofsermarcopo001polo/page/45; accessed on November 25, 2019).

- [3] Ibn Battuta, collated and translated by H. Adjarian, Yerevan, 1940, page 31; Karnig Sdepanian, Yerzenga [Erzindjan], Yerevan, 2005, page 400; Arapagan Aghpurnere Hayasdani yev Harevan Yergrneri Masin [Arab Sources on Armenia and Neighboring Countries], collated by H. T. Nalpantian, Yerevan, 1965, page 30.

- [4] T. A. Sinclair, Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archaeological Survey, Volume II, London, Pindar Press, 1989, page 290.

- [5] Ibid.

- [6] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, Cairo, 1947, page 106.

- [7] A-To, Vani, Bitlisi, yev Erzurumi Vilayetnere [The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis, and Erzurum], Yerevan, 1912, page 220.

- [8] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 189. K. Srvantsdyants, who visited Erzindjan in 1878, also linked the development of the city and region with the stationing of army troops there, as well as the fact that the city was located at the crossroads of south-to-north and west-to-east roads, adding the following evocative comment: “Yerzenga is a historic city, and just as it is famous for its rich religious offerings, it is known for its past, in which it had been plundered by foreign invaders and destroyed by earthquakes on a regular basis. In the present time, however, it is gradually developing, thanks to our gracious Ottoman Empire, which stationed a contingent of army soldiers there. The presence of troops and officers has restored safety in the city, and from the ruins have risen beautiful buildings, active trade, crafts, and civilization. The people of Yerzenga benefit from being in direct communication with the provinces and provincial authorities of Sepasdia, Kharpert, all of Dersim, Garin, and Drabzon.” (Father K. Srvantsdyants, Toros Aghpar [Brother Toros], Part B, Constantinople, K. Baghdadlian Press, 1885, page 48).

- [9] Carpentry was an exception, and usually practiced by Turkish craftsmen (Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 163).

- [10] Hayots Tseghasbanoutyune Osmanian Tourkiayoum: Verabradzneri Vgayoutyunner: Pasdatghteri Joghovadzou, Hador III, Erzurumi, Kharperti, Diyarbakiri, Sepasdiayi, Drabzoni Nahankner, Barsgahayk [The Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey: Survivor Testimonies: Anthology of Documents, Volume III: The Provinces of Erzurum, Kharpert, Diyarbakir, Sepasdia, Trabzon; Persian-Armenians], chief editor A. Virapian, Yerevan, Armenian National Archives, 2012, page 184 (document n. 41 contains Karekin Tourigian’s testimony regarding the massacres in the Armenian villages of Yerzenga).

- [11] Hovhannes Zadigian, Garini Nahanke XIX Tari Yergrort Gesin [The Province of Garin in the Second Half of the 19th Century], Yerevan, 2013, page 364.

- [12] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 189.

- [13] Ibid.

- [14] Vital Cuinet, La Turquie d’Asie, t. 1, Paris, 1892, page 216.

- [15] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 177 and page 190.

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] Ibid., page 188.

- [18] For a detailed description of the massacres in Erzindjan, see “Letter from Turkey,” Armenia, Marseille, November 30, 1895, number 35, page 1.

- [19] Surmenian, Yerzenga, pp. 190.

- [20] Ibid., page 165.

- [21] Ibid., pp. 165-166.

- [22] S. M. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [The Land of Western Armenia], New York, 1947, page 163.

- [23] Surmenian, Yerzenga, pp. 165-166.

- [24] In the villages, women were usually the ones who engaged in the production of Manisa cotton (S. Amadian, “The Yegheghyats District: A Description of Armenian-populated Villages,” Arevelyan Mamoul National and Political Monthly, Smyrna, April 1891, page 158.)

- [25] G. D. Khachadourian, “Geography: Yerzenga or Yeriza,” Masis National and Political Weekly, Constantinople, September 27, 1886, number 3841, page 140.

- [26] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 177.

- [27] Ibid., page 178.

- [28] Ibid., page 179.

- [29] Ibid.

- [30] V. K. Proudian, Kavaragan Getronner [Provincial Centers], Puragn National, Scientific, Literary, and Political Review, Constantinople, 1905, November 26, number 47, page 919.

- [31] Giragos S. Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner Oughevoroutyan [Mixed Travel Correspondence], Constantinople, Sareyan Press, 1887, page 24.

- [32] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 180.

- [33] Ibid., page 91.

- [34] Ibid., page 180.

- [35] Ibid., page 181.

- [36] Ibid., page 169.

- [37] Thigh boots.

- [38] Ibid.

- [39] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 170; Karnig Sdepanian, Yerzenga (Hnakouyn Tarerits Minchev Mer Orere) [Erzindjan (From Ancient Times to the Present Day)], Yerevan, University of Yerevan Press, 2005, page 399.

- [40] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 170.

- [41] Ibid., page 171.

- [42] A Craftsman, “Crafts in the Provinces,” Arevelyan Mamoul, Smyrna, November 15, 1901, number 22, page 922.

- [43] Ibid.

- [44] Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 170.

- [45] Ibid., page 171.

- [46] Ibid., page 172.

- [47] S. Amadian, “The Yegheghyats District: A Description of Armenian-populated Villages,” Arevelyan Mamoul, Smyrna, March 1890, page 139; Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 172.

- [48] Ibid., pp. 172-173.

- [49] Ibid., page 173.