Erzindjan/Erzincan/Yerzenga – Schools

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 12/05/19 (Last modified 12/05/19) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Armenian Population of the Erzindjan Sub-district in the Second Half of the 19th Century and the Early 20th Century

The Erzindjan Sub-district (Kaza), located in the Erzindjan District (Sandjak) of the Erzurum Province (Vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire, stretched over approximately the same territory as the Yegeghyats District of Greater Hayk’s Upper Hayk Province, including the vast field of Erzindjan. The sub-district bordered Papert in the north, Terchan in the east, Dersim (Harput Province) in the south, and Gamakh and Gerdjanis in the west [1].

The field of Erzindjan was described as fertile and water-rich. The mountains that surrounded it were beautiful and covered with green grass. Erzindjan’s climate is temperate – mountainous in certain areas; and the warm climate of valleys in others [2].

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the Erzindjan Sub-district included 120 settlements, of which 32 (or 37, if the farm communities known as mzres and palangas are included) were Armenian-populated. Of these, 11 were exclusively Armenian-populated [3]. The City of Erzindjan, the administrative center of both the district and sub-district, was the second most populous city of Erzurum Province [4]. According to the 1913 census conducted by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate [5], the sub-district’s Armenian population was 25,795, of whom 13,109 (2,021 households) lived in the City of Erzindjan, and 12,686 in the sub-district’s Armenian-populated villages [6]. Armenians comprised about a third of the population of both the city and the sub-district [7].

The State of Education among the Armenians of Erzindjan Prior to 1878

Like in other areas of the Ottoman Empire and Ottoman Armenia, prior to the 19th century, Armenian educational institutions in the Erzindjan Sub-district operated mostly within monasteries, and in isolated instances, within local churches. The monastic seminaries educated future monks, while church schools prepared the next generation of priests, deacons, and other clergymen [8].

Individual schools and “classrooms” began appearing in the capital Constantinople and Smyrna in the late 18th century. They began appearing in the provinces some time later, in the early 19th century. These schools and classes were established and run by individual clerics or laypeople [9].

In 1789, Ottoman Sultan Selim III, in his efforts to introduce reforms that would bring about the westernization of his country, gave the Ottoman Armenian and Greek minorities the right to establish their own secular or neighborhood/“azkayin” (parochial) schools, which would be administered by neighborhood councils that operated alongside church parishes [10]. With the permission of the Ottoman authorities, Armenian neighborhood/parochial schools were opened in Constantinople in the 1790s, and already by the 1800s they began opening in the empire’s provinces.

The educational/cultural revival of Ottoman Armenians was spurred on even more on July 10, 1824, when Patriarch of Constantinople, Garabed Balatsi III, issued a special decree that instructed all churches under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate to “establish schools for the edification of the children of the church” [11].

According to the survey conducted by the Constantinople Patriarchate in 1834, there were 114 Armenian schools operating in the Ottoman Empire outside of the capital. Among these was one school operating in Erzindjan (unfortunately, this source provides no additional information regarding the school’s enrollment or faculty) [12]. Another source indicates that the first school to operate in the City of Erzindjan was the parish school of the city’s Saint Nshan Cathedral [13].

Our sources provide more detailed information concerning educational activities in Erzindjan from the early 1850s onward. Giragos Ghazandjian, a native of Erzindjan, mentions that during this period, one “azkayin” school operated in the city, with an enrollment of 140 pupils, consisting of 100 boys and 40 girls [14]. The school’s yearly operating cost was 10-20 Ottoman pounds, provided by the Prelacy. The school offered a seven-year course of studies (Ghazandjian himself had attended the school from 1849 to 1856). The school offered classes in Armenian (reading and writing), liturgical music, pokh (the reading and interpretation of excerpts from the Bible), and the delivery of sermons. The school’s textbooks included the Keragan, Hezaran (primer), Saghmos, Kordzk Arakelots (voluntary), and Nareg. The school also occasionally provided instruction in Turkish [15].

One teacher and one priest taught permanently at the school. G. Ghazandjian was particularly impressed by the gifted pedagogue and grammar teacher Avedis Zoulalian, who spent a year teaching in Erzindjan [16].

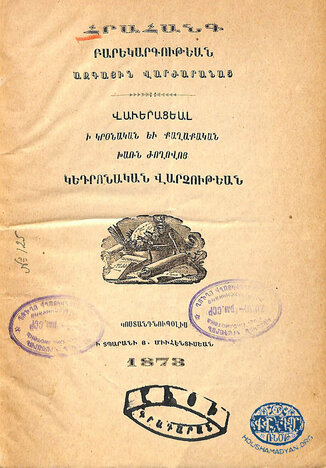

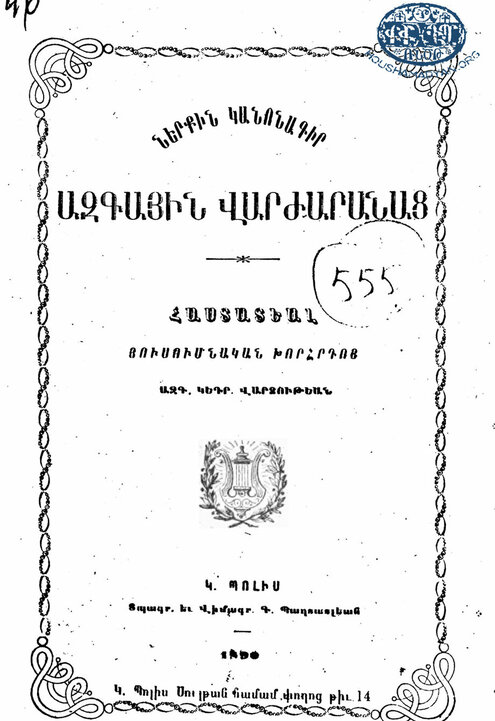

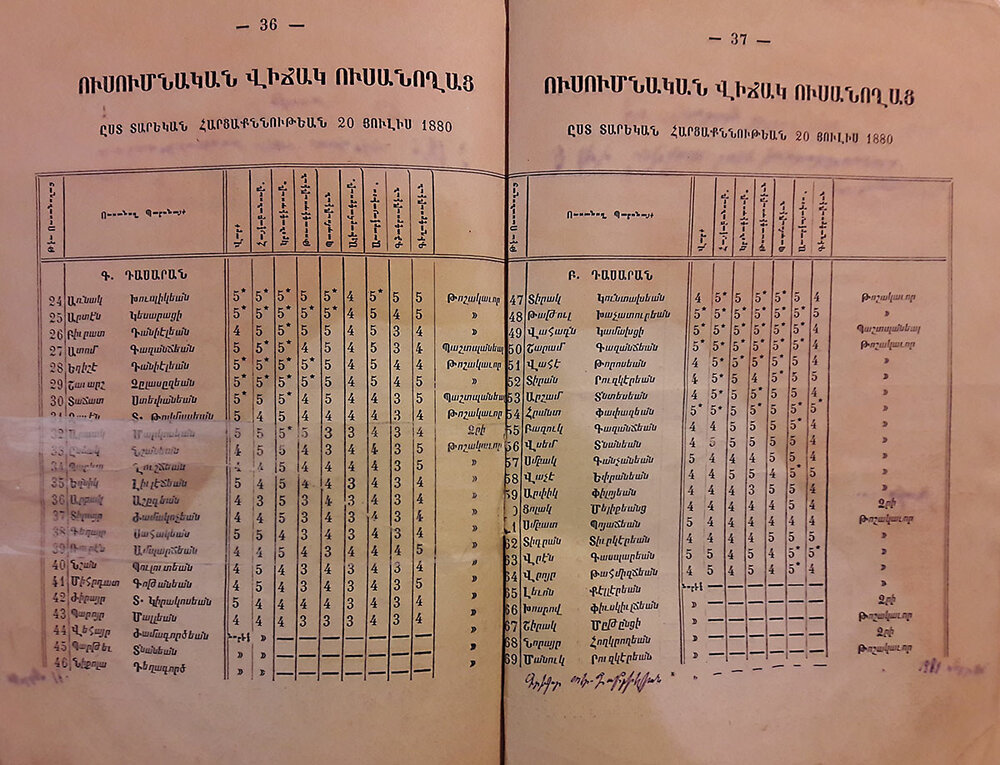

1) The decree ordering reforms of parochial Armenian schools, Muhendisian Press, Constantinople, 1873.

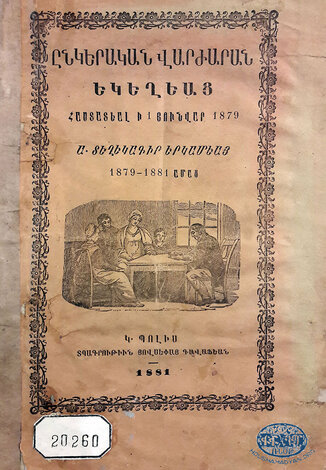

2) The Association School of Erzindjan, two-year report, 1879-1881, Hovsepa Kavafian Press, Constantinople, 1881.

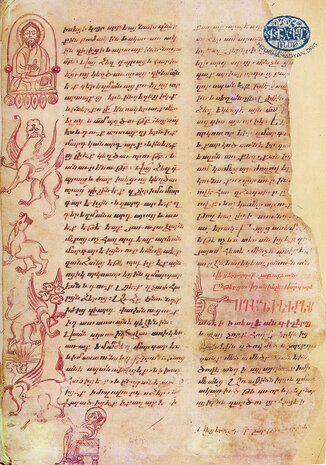

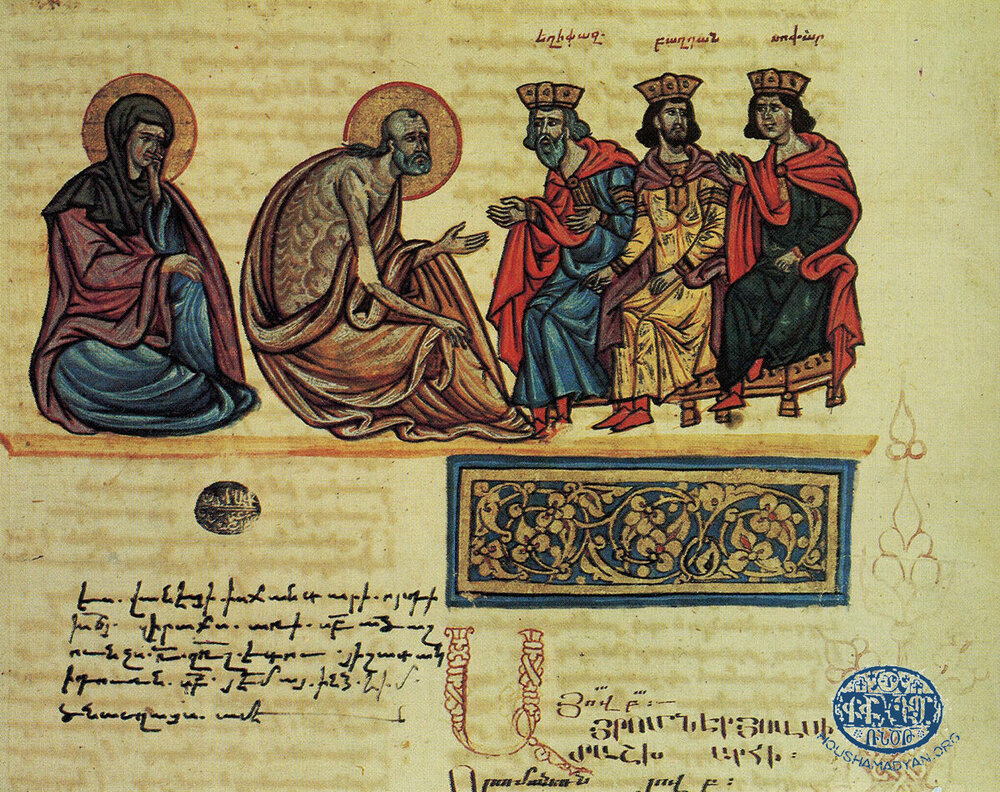

3) The Vision of Daniel, Painter: Sarkis, 1362, Yerznga, Ms 4519 (Source: Armenian Miniatures from the Matenadaran Collection, Nairi Publishing House, Yerevan, 2009)։

G. Ghazandjian provides vivid descriptions of how discipline at school was enforced with the use of the cane and the falakha (bastinado). The main goal of the school was to provide a Christian religious education. “Morning and afternoon, classes began and ended with the recitation of prayers. We were duty-bound to attend church. We were taught, and most of us learned to recite, the Yegestse, Havadov, Mer Amenagal, Voghormya, and other prayers, as well as many hymns, pokhs, and sermons” [17].

The same source mentions that in the 1840s-1850s, parochial schools also operated alongside churches outside of the city, in some of the larger Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district [18]. At this time, the style and methods of schooling in the countryside did not differ from those in the city.

As in other Armenian-populated parts of the Ottoman Empire, the advancement of education in Erzindjan went hand-in-hand with the growth of educational and “cultural” organizations created for the purpose. The Saint Nersesian Association was founded in 1848, and is the oldest such organization mentioned in our sources [19].

Between 1856 and 1859, the Lousavorchian Association was particularly noted for its work. The organization’s mission was to support the school attached to the Holy Trinity Church of Erzindjan (which would later become the Central School) [20].

After the ratification of the Armenian National Constitution in 1860, the field of education continued to experience steady and continuous growth in Erzindjan, as it did in other Armenian-populated areas of the Ottoman Empire. The Constitution codified a system of governance for Armenian schools that survived, without any appreciable changes, until the Armenian Genocide. A national educational council was formed, known as the Constantinople National Educational Council, consisting of seven laymen elected by the Diocese Clergy Conference and functioning alongside the Armenian Patriarchate. This council was tasked with the enormous responsibility of overseeing the education of Ottoman Armenians. Its specific priorities were the overseeing of reforms of parochial schools; the provision of support for the educational-“cultural” organizations that had been created to support education in Ottoman Armenia; the preparation of “highly skilled” teachers; the dissemination of textbooks, etc. The National Educational Council was also responsible for the development of standard curricula for “azkayin” schools, the development of templates for graduation diplomas, and other similar tasks (see The National Constitution of Armenians, article 45) [21].

The local neighborhood councils of Armenian towns and villages, and the school boards of trustees they appointed, provided immediate oversight of “azkayin” schools operating in their parishes. They also attended to the schools’ immediate needs. The neighborhood councils were expected to use resources from their “coffers” (budgets) to ensure the uninterrupted and smooth operation of their schools. These funds were obtained from neighborhood taxes on the locals, income from the local church and school properties, endowments, gifts, etc. The neighborhood councils were required to contact the Constantinople National Educational Council to resolve any issues that arose in the running of schools [22].

During this period, the National Educational Council began putting into circulation the educational program that it had developed for the “azkayin” schools of the Ottoman Empire. The program was modeled on European, specifically French educational programs. It delineated the kindergarten, primary, elementary, upper elementary, and secondary levels of schooling. For each level, it specified the subjects that had to be taught, the number of classes for each subject, the duration of classes, and the acceptable forms of reward and punishment. The program also established divisions of classrooms; the classification of schools; and the schedule of classes, recesses, lunch breaks, holidays, etc. “Azkayin” schools also began adopting new methods of evaluating and assessing students’ aptitude and progress, conducting final examinations, and distributing diplomas upon graduation [23].

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, in addition to the Yeznigian School operating alongside the Saint Nshan Cathedral and the Lousavorchian School operating alongside the Holy Trinity Church, two new neighborhood schools were established in the City of Erzindjan – the Aramian School (affiliated with the Saint Sarkis Church) and the Naregian School (affiliated with the Holy Savior Church). Aside from these, in the 1870s, the Chrisdinian Girls’ School was founded in the city (1875), as well as the co-educational Torkomian and Haigaznian private schools, which charged tuition fees to fund their operations. Preparatory “kindergartens” were also opened alongside all these school. The four neighborhood/”azkayin” schools of the city, as well as the Chrisdinian Girls’ School, continued to operate up until the Armenian Genocide.

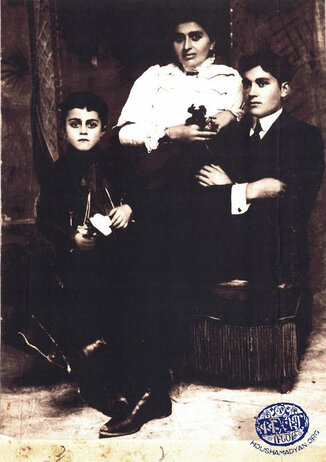

1) Erzindjan, circa 1909. From right to left – Haig Mordjigian, his sister Hayganoush Baronian (nee Mordjigian), and an unidentified child (Source: Thompson/Nielsen Collection, Iowa City (IA) and Berkeley (CA), USA).

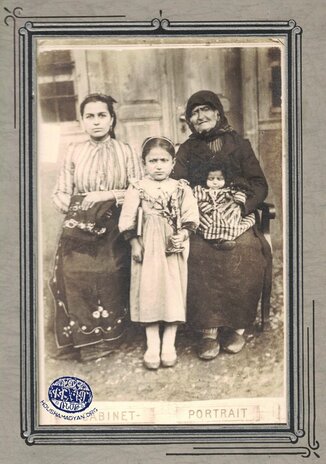

2) Erzindjan. From left to right – Hayganoush Baronian (nee Mordjigian), Miriam Shakardjian (the standing girl), and Helen Shakardjian (nee Shamegian). The child in Helen’s lap is probably Sherman Baronian, Hayganoush’s son (Source: Thompson/Nielsen Collection, Iowa City (IA) and Berkeley (CA), USA).

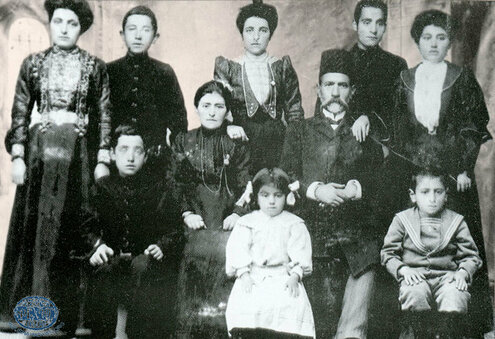

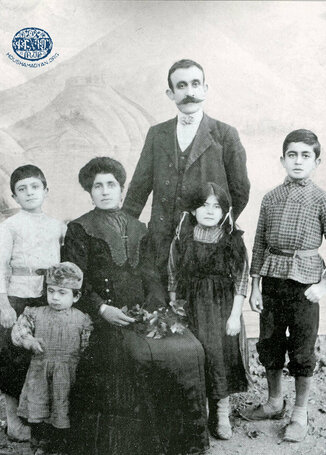

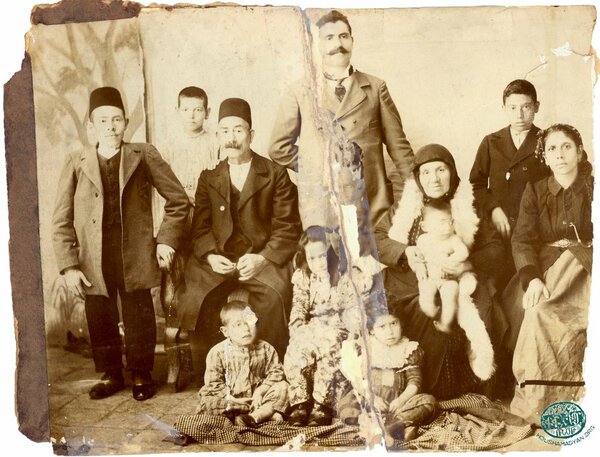

3) Erzindjan, 1885. The Yourouzgerian family (Source: Karnig Sdepanian, Yerzenga/Erzindjan: from Antiquity to Today, Yerevan State University Press, Yerevan, 2005).

According to the survey conducted by the Erzindjan Prelacy in April 1878 on behest of the Armenian Patriarchate, combined enrollment in the seven aforementioned schools totaled 900 pupils, of whom 600 were boys and 300 were girls [24]. Other schools operated in 20 Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district, with a combined enrollment of 720 pupils (no information is provided on the number of students from each sex) [25]. Thus, in 1878, a total of 27 schools operated in the City of Erzindjan and the villages of the sub-district, with a total enrollment of 1,620 pupils.

According to a testimony reflecting the situation in the 1870s and 1880s, “Four neighborhoods [in the City of Erzindjan – ed.], more developed than the others, have their own schools, their own leaders, and their own administrations. These neighborhoods are competitors and rivals … Each parish and neighborhood council jealously protects its neighborhood’s interests and strives to improve its financial situation, with the ultimate aim of improving the local school. Each church now has a school attached to it, funded partly by the church and partly by the students’ tuition fees” [26].

Senior Priest Boghos Natanian, who visited Erzindjan in May 1878, reported that the city’s educational institutions were housed in newly-built, spacious, and well-lit two-story buildings; and that the teachers working in these institutions were “skilled and well-versed in Armenian.” B. Natanian described the people of Erzindjan as supporters of education and progress, as evidenced by the stellar condition of their schools [27].

In less stellar condition were the neighborhood schools of the sub-district’s villages. They mostly operated intermittently, usually only in the winter months. During the other seasons of the year, the pupils helped their parents with farm work [28]. Education in village schools was typically limited to elementary instruction in grammar, the Saghmos, the Nareg, catechism, mathematics, and liturgical music, all taught by the village priest or teacher [29].

Armenian Education in Erzindjan in the 1880s: The Association School and the Saint Nersesian Boarding School

The growth that the Armenian educational field had experienced in Erzindjan in the 1870s accelerated after the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish War. By then, the Armenian Issue had become an item on the international diplomatic agenda. Gradually, Western Armenians were attaching more importance to the growth of a shared national consciousness. Their willingness to insist upon their rights was growing correspondingly. Armenian intelligentsia saw progressive education in the national spirit as the means by which the Armenian nation could obtain recognition of its rights. Schools were now seen as crucial cauldrons for the creation of the Armenian national consciousness and the launching of a new national awakening [30].

The Ottoman-Armenian educational renaissance that began in this period penetrated even the darkest corners of Ottoman Armenia. On June 1, 1880, three organizations operating in Constantinople – the Araradian, Scholastic-Oriental, and Cilician educational organizations – merged to create the United Association of Armenians (or United Association for short). The stated aim of the United Association was to support educational initiatives and the expansion of the network of Armenian schools in Ottoman Armenia (specifically in Cilicia and the six Armenian-populated provinces of Van, Bitlis, Erzurum, Diyarbakir, Kharpert (Harput) and Sebastia (Sivas) [31]). After this merger, in the early 1880s, the United Association established some 24 new schools. By the mid-1800s, its network of schools consisted of approximately 50 institutions [32]. In 1881, it established the Sanasarian secondary (intermediate) school in Garin.

The Armenians of Erzindjan, imbued with patriotism, actively participated in the developments in the field of education. Two new educational institutions were established in Erzindjan – the Erzindjan Association School and the Nerses Patriarch Boarding School (also known as the Saint Nersesian Boarding School). Below, we will examine the work of these two institutions in detail.

When he visited Erzindjan in the May of 1879, renowned Armenian church official Father Karekin Srvantsdyants happily reported the great regard the locals had for education and schooling, as well as the results of the recent growth in the educational arena. “There is a cadre of honorable youth in the city, some of whom contributed to the establishment, and still regularly and effectively manage the operations, of the Association School. The Chrisdinian Girls’ School and Central Boys’ School are the pride of Erzindjan, and are revered by the locals, as are the toddlers’ primary schools and the organizations established to support education” [33].

According to information from 1886, eight “azkayin”/neighborhood and private schools operated in the City of Erzindjan. Total enrollment stood at 1,050 pupils, of whom 600 were boys and 450 were girls. The total number of teachers was 34, 20 of whom were male, and 14 female. Two of the teachers working in Erzindjan were from Istanbul, while the others were graduates of the local schools (Central School, Association School, and Nersesian School). All these teachers had diplomas or certificates of school graduation, and some also had teaching certifications from the National Educational Council. The combined budget of the schools was 650 Ottoman pounds, which was secured from tuition fees, fundraisers, and neighborhood council taxes. Additionally, the schools of Erzindjan received financial and moral support from the United Association and Association of Armenian Women, the former supporting the Central School and the latter supporting the Chrisdinian School. The parochial, private, and Association-supported schools in Erzindjan all had their own educational programs and curricula, and each school’s course of studies was determined by the timeframes stipulated in these educational programs [34].

During this period, Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian, Prelate of the Erzindjan Diocese from 1880 to 1886, contributed greatly to the development of education in Erzindjan. One of his contemporaries provided the following description of his efforts – “Timaksian cherished and supported the churches and schools, as well as all efforts aimed at the edification and advancement of the people. During his term, the administration of all parochial schools was put on the right course, particularly the Chrisdinian Girls’ School and the Saint Lousavorich School of the Holy Trinity Church, which later became the Central School. He founded the Saint Nerses Boarding School, and also oversaw the construction of the prelacy and Armenian cemetery. It was thanks to his encouragement that the youth succeeded in founding the city’s first theater. He would often visit the schools and attend lectures and examinations. He presided over award ceremonies and discussions concerning the schools, and took practical steps to support both students and teachers” [35].

The Erzindjan Association School

The Association School was founded on January 1, 1879, with the patronage of Erzindjan’s “earnest and enlightened” local community leaders (Hagop-Shavarsh Kenirdjian, Mgrdich Tanielian, Hovhannes Tanielian, Hagop Bedrosian, and Pilibos Boyadjian). The institution was a secondary (intermediate) school, and its mission was to provide the children of the City of Erzindjan and the sub-district with the best possible education, based on the most modern practices, thus allowing them to receive first-rate schooling from the primary to the secondary level. “The school was established to provide Armenian children with the type of education and schooling that would allow them to later contribute to the Lord and to the nation. Spiritual education is a priority. Graduates are expected to be humane and virtuous, and to cherish the Armenian Church and Armenian traditions,” states one of the school’s own documents [36].

Initially, the course of studies offered by the school spanned seven years (three years of primary (elementary) schooling and four years of secondary (intermediate) schooling) [37]. Later, this was increased to eight years (four years of primary (elementary) schooling and four years of secondary (intermediate) schooling) [38]. The school was housed in the rented premises of the newly-built Naregian School building, the neighborhood school attached to the Holy Savior Church [39].

In its first year of operation, the school had three primary classrooms, with an enrollment of 50 pupils. Enrollment reached 70 in 1880, 116 in 1881 (six classrooms), and 125 in 1884. In principle, the school was designed to accommodate a maximum of 140 pupils [40]. Tuition fees were waived for students from indigent families (26 in 1880; 30 in 1884). The school attempted to fund their education through donations and fundraisers, as well as the innovative practice of “sponsorship” by benefactors. In 1881, the number of students “sponsored” in this fashion was eight [41]. The school often appealed to the community for donations via the local press. One notice disseminated by the school administration on March 16, 1884 reads – “With your contribution of one Ottoman pound per year, a child from the villages can receive an education, changing the life of an entire family” [42].

The school offered classes in catechism; ethics; classical and modern Armenian; Armenian literature; Turkish, French, Armenian, Ottoman, and general history; arithmetic; accounting; bookkeeping; natural sciences; geography; character development; drawing; music (including musical notation and singing)’ calligraphy (Armenian, Turkish, and French); and physical education [43].

The school had its own internal regulations, which outlined its admission policies, the duties of students, acceptable methods of reward and punishment, rules governing examinations, etc. [44].

Education was conducted using “new and more straightforward” methods, and efforts were made to continually refine these practices. The school adopted two fundamental educational principles – “1. Pupils must be taught according to their physical and mental capabilities. Lessons should be simple, brief, easy to grasp, and at the same time entertaining; 2. Teachers must strive to ensure that students learn consciously and comprehensively, understanding concepts rather than learning by rote” [45].

The school’s teaching guidelines also emphasized that teachers, as the “true friends and partners of students,” must treat them with great respect and “with affection,” and must attempt to kindle in their hearts the traits of honor and magnanimity. Violence, corporal punishment, and other “outdated and extreme practices” were to have no place within the school [46].

In 1880, with the purpose of supporting the school, its graduates and faculty formed the school’s alumni and teachers’ associations. The latter specifically had the following aims – “1. To create true friendship, honest dialogue, and a sense of mutual respect between students and staff…; 2. To encourage freedom and confidence among the students; 3 – And to develop and implement educational practices aimed at the greater edification of students” [47].

The prestige of the Association School, the role it played in the city, and its reputation as a “model school” were predicated on the talent and skills of its faculty. In 1881, the school had four permanent teachers [48], who were:

- Teacher and principal Sarkis Amadouni (Amadian), who taught French, Turkish, history, and geography;

- Bedors Poharian, who taught Armenian, catechism, natural sciences, arithmetic, musical notation, and drawing;

- Mgrdich Torosents, who taught arithmetic and bookkeeping;

- Jirayr Vasgouni, who taught physical sciences, arithmetic, character development, and physical education [49].

Alongside the rise in the school’s enrollment came an expansion of its faculty. Thus, in 1884, the school had 11 teachers, of whom 6 were permanent, and 5 were visiting teachers [50]. The school’s teachers lived very Spartan lives, keeping themselves from any temptations. The lifestyle of its teachers contributed even more to the school’s reputation among the locals, resulting in even greater improvements of the school’s practices and the further expansion of enrollment [51]. During its first years of operation, the Association School received accreditation from the National Educational Council; was honored in a special decree issued by Archbishop Nerses Varjabedian, Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople; and received the praise of many visitors [52].

Four years after its establishment, in 1883, the Association School produced its first class of graduates, consisting of 20 pupils. A few of them left for Constantinople to continue their studies (the school’s board of trustees secured educational scholarships for them), while some others were hired by the school as teachers. Many others became teachers in village schools across the sub-district [53].

However, with its expansion and the growth of its student body, the Association School more urgently faced its greatest challenge – the lack of resources. The school’s funding came from the students’ tuition fees, as well as the donations of various organizations and individuals. Despite the best efforts of the school’s board of trustees, these donations did not keep pace with the growth in enrollment. The attitude adopted in the 1880s towards the school by Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian, the Prelate of Erzindjan, did not help. He prioritized support for neighborhood/“azkayin” schools, and saw the Association School as a competitor of these parochial institutions. As a result, though he did not exhibit any hostility towards the school, he also did not exhibit any favor towards it, nor was he in the least concerned with its situation. He even abstained from attending events and celebrations organized by the Association School. In its turn, the administration of the school wasted no opportunity to rebuke and criticize Timaksian [54].

As a result of these circumstances, beginning in 1882, the Association School operated with a deficit in its budget, which grew every year. Even the yearly contributions from the United Association were insufficient to balance the school’s budget. S. Amadian, unable to overcome these financial challenges, resigned from his position as principal. He was replaced by Mihran Khortoumdjian, who was a man of strong character and willpower. He was successful in reforming the budget, thus ensuring that classes continued to be held regularly. However, the school’s board of trustees failed to increase the institution’s revenues, as a result of which the school was permanently closed in 1886, having “shined like a star for six-seven years in the firmament of the field of education in Erzindjan” [55].

The Prelate Saint Nerses Boarding School (Saint Nersesian Boarding School)

The establishment of a boarding school at the Prelate Saint Nerses Monastery (seven kilometers south-east of the City of Erzindjan) became the most important educational initiative launched by Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian, who was appointed Prelate of the Erzindjan Diocese in early 1880. The principal mission of the boarding school was to prepare the next generation of teachers and priests who would serve in the Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district [56].

A special building was built on the monastery grounds to house the school. The building had a large dormitory, classrooms, and learning rooms, all specially designed with children in mind [57].

The school began operating in 1882, with an initial enrollment of 30 pupils. On Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian’s instructions, the school prioritized the admission of poor, but gifted children from the large Armenian-populated villages of the region. Madteos Torosian, who had graduated from the renowned Armash Seminary, was appointed schoolmaster. Musicologist Khachig Durgerian was appointed the school’s custodian [58]. In later years, enrollment reached 40 pupils, and the number of staff and faculty reached 10 [59].

As the monastery could not cover the costs of operating the school from its own budget, Prelate Timaksian obtained gifts and raised funds from other sources to fund the school. A contemporary testimony reads – “A few of the wealthy citizens of the community, with yearly sponsorship contributions, funded the education of one student each. Additionally, each village that had a student attending the school provided wheat, beans, hay, lumber, vegetables, and other supplies as payment” [60].

The school was not self-sufficient. Its continued existence depended on the funds allocated to it from the diocese authorities, which were secured thanks to the personal efforts of the Prelate. Prelate Timkasian was able to keep the school open for as long as he retained his office. However, he was relieved from the position in 1886 and left Erzindjan. As a result, the school was unable to overcome its financial challenges and closed shortly thereafter [61].

Even though the school operated for a mere four years, according to contemporaries, in its short life it produced a large number of well-educated and cultivated graduates, many of whom would later play an important role within the Erzindjan Armenian community. About 10-15 of the school’s graduates would also become teachers working in village schools across the sub-district [62].

The establishment of the boarding school gave new life to the Saint Nerses Monastery. The monastery buildings were renovated, and its lands and other estates thrived [63].

Public Education in Erzindjan in the 1890s: The Issue of the Unification of Schools

After the dismissal of Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian and the closure of the Saint Nerses Boarding School and the Association School, educational activity in Erzindjan experienced a period of relative stagnation. Efforts now focused on improving “azkayin”/neighborhood and village schools. The problems in the educational arena were exacerbated by the Hamidian massacres, which were an economic shock for all of Erzindjan, also affecting the revenues and financial wellbeing of neighborhood schools and other educational institutions. The wave of persecution launched by the Ottoman authorities after the 1895 massacres was a particularly great blow to the Yeznigian School. One of its teachers, Bedros Pogharian, and two of its trustees, Haroutyun Lepian and Ghazarosian, were accused of conducting revolutionary activities and arrested. The school was temporarily shut down [64]. Under these circumstances, the issue of the unification of Erzindjan schools became relevant.

As early as the 1860s-1870s, in response to the fact that four different schools and educational systems were operating in Erzindjan, sensible intellectuals and educational leaders began raising the possibility of a unified educational system. The advocates of such a system argued that it would give the community the opportunity to concentrate its efforts and substantially improve the quality of education. A centralized system would, among other things, be more capable of providing education to indigent children whose families could not pay [65], allow for the implementation of a unified curriculum and educational program, and attract a cadre of high-quality teachers.

In the mid-1890s, former principal of the Association School, Sarkis Amadian, perhaps with some level of hyperbole and exaggeration, described the challenges facing the Armenian community of Erzindjan in the field of education – “And so, the intelligent segment of the community realizes that despite the reputation of the people of Erzindjan as supporters of education, educational efforts there have been foundering for 20-30 years. It is true that some isolated azkayin and neighborhood schools, boarding schools, and other educational institutions have implemented some reforms, but these reforms have lacked the continuity which is necessary for results. The children of workers and the poor are always deprived of education, and the education of girls is completely ignored. Neighborhood schools claim to be able to simultaneously offer primary, intermediate, and secondary classes, but have failed to do so on repeated occasions. The four different churches, with their four different schools, neighborhood councils, boards of trustees, faculties, and parishes repeatedly undermine each other’s efforts and engender division and enmity” [66]. Amadian, who had great insight into these problems, saw the solution in the unification of the individual schools.

Another advocate of unification was the young, educated Father Daniel Hagopian, who had assumed the mantle of Prelate of Erzindjan in 1897. At his initiative, in the summer of that same year, the Provincial Council gave its approval to the plans for unification [67]. However, these efforts were fraught with difficulties from the very outset. In particular, the neighborhood council of the sub-district’s wealthiest church parish, the Holy Trinity, opposed the initiative and refused to take part in it. Nevertheless, in early 1898, the neighborhood councils of the Saint Nshan, Saint Sarkis, and Holy Savior churches merged, with the corresponding merger of the Yeznigian, Aramian, and Naregian schools. The Yeznigian and Aramian schools became elementary schools, one of them co-educational, with a shared administration, faculty, and educational program. The Naregian School became a learning institute (secondary school). Total enrollment after the merger was around 600, with a faculty of 17 teachers [68].

However, income from tuition fees and from the parishes’ estates was not sufficient to meet the needs of the merged schools. The wealthy residents of the Armenian neighborhoods were now also more reluctant to open their purses to help the new institutions that had no direct affiliation with their neighborhood churches. As a result, the deficit in the school’s budget grew every year. In 1900, the Erzindjan Provincial Council attempted to resolve the problem by forcing the Holy Trinity Church to join the merger. This, however, resulted in the exact opposite. The neighborhood council of Holy Trinity resolved to vehemently oppose any decisions made by the Provincial Council or even by the Constantinople National Educational Council. Under these circumstances, the members of the Provincial Council, especially in view of the ambiguous stance of the prelate, were unable to enforce their decision, and convinced that it would be pointless to continue, tendered their resignations. This was followed by resignations of the neighborhood councils, and later the educational councils, of the three merged parishes. As a result, this short-lived merger ended, and the educational field in Erzindjan returned to its previous state, with the re-establishment of four different schools [69]. We must note, however, that this separation of the City of Erzindjan into four neighborhoods and four separate parish schools had its benefits, as well as its drawbacks. It encouraged competition between the neighborhoods, which led to the continuous improvement of the schools [70].

Despite this unstable situation in the educational field in Erzindjan in the 1890s, the number of pupils in the city’s and villages’ schools continued to slowly, but steadily grow. According to the 1902 survey, 22 “azkayin” schools operated in the Erzindjan Diocese, five of which were in the city, and 17 in the Armenian-populated villages. Enrollment was 1,864 pupils, of whom 1,389 were boys and 475 were girls. The teachers numbered 63, of whom 54 were men and 9 were women (for information on each village, see the applicable section of this article) [71]. This was a slight improvement compared to the numbers from 1878, when total enrollment in the schools of the city and villages stood at 1,620.

Nevertheless, many schools across the area, particularly in villages with small populations of Armenians, shut due to the lack of financial resources. Moreover, in some villages, the parlous condition of school buildings forced teachers to hold classes in private homes [72]. Already in 1897, Prelate Daniel Hagopian noted that a large number of the diocese’s schools existed only on paper, and their buildings were simply left vacant [73].

Education among the Armenians of Erzindjan after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution brought about an easing of the persecution of Armenians across the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in improvements in the social, political, economic, and cultural-educational arenas of Armenian life in Erzindjan.

Advances in the educational field in Erzindjan particularly manifested themselves in the active work of cultural and educational organizations in the area. In this period, the educational organization that most distinguished itself was the Yegeghiats (Erzindjan) Scholastic Union, which was formed in 1909 with the merger of two other organizations, the Grtasirats (Scholastic) Association (formed by graduates of the Yeznigian School) and the Yegeghiats Association. On the eve of the Genocide, the Scholastic Union had 500 members, most prominent among whom were Kourken Lazian, Terenig Djizmedjian, Armenag Melikian, and Kegham Sahagian [74].

With its library, oration, and theater groups, the union energized cultural and educational efforts in the region. Among its accomplishments were the opening of a library/reading room with a collection of thousands of Armenian books; the organizing of periodic lectures on various relevant and pertinent societal and political topics (such as the collectivization of farms, the origins of religion, the Ottoman Constitution, oppressed nations, Marx's Das Kapital, the life of Khrimian Hairig, etc.); and the staging of various plays (Muratsan’s Ruzan, Shirvanzate’s Namous, Aharonian’s Artsounki Hovide, etc.) [75].

The Erzindjan Scholastic Union received support from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnak Party). Many of the union’s members were also members of the party [76], as were many of the teachers working in the city and village schools.

After the Young Turk Revolution, the unification of the schools of Erzindjan was once again proposed. Work towards this goal began as early as 1908. However, the successful unification of the Yeznigian and Aramian schools was not finalized until early 1910. The board of trustees of the combined school was able to double its revenues, as well as to attract a select group of experienced, effective, and reliable teachers. It was reported that locals had been able to secure enough funds to pay for the tuition of approximately 100 children from indigent families. Each individual or household had “sponsored” one pupil, donating one Ottoman pound per year (this system had previously been implemented by the Association School, and had apparently later been adopted by other neighborhood schools in Erzindjan) [77]. However, this merger between the Yeznigian and Aramian schools was short-lived. Sources indicate that by 1913, the two schools were once again operating separately.

Advances in the educational field in Erzindjan in the 1910s owed much to the efforts of a newly elected educational council, whose members were Zarmayr Djermagian (principal of the Central School), Mamigon Varjabedian (a renowned pedagogue, a native of Keghi by birth), Bedros Srabian (one of the most celebrated former teachers of the Association School and the principal of the Yeznigian School), Bedros Pogharian (a former teacher of the Association School, later principal of the Chrisdinian Girls’ School), and Boghos Mardirosian [78].

Between 1908 and 1914, efforts to reform the sub-district’s village schools were renewed. New school buildings were renovated, particularly in the larger villages (Mtni, Mahmoudtsik, Meghoutsig, etc.) A new six-year course of studies was adopted by the village primary schools (for additional details regarding each of these villages, see the applicable section of this article).

Like in other regions of Ottoman Armenia, the development of effective primary education in the villages of Erzindjan owed much to the organizations and associations formed overseas by migrants from Erzindjan (especially in the United States). These organizations’ goal was to provide financial support to maintain village schools and improve the educational system in the sub-district.

As we previously noted in our article on schools and education in Keghi, the lack of archival sources regarding the activities of Armenian organizations functioning in Ottoman Armenia often forces us to rely on isolated, occasional reports in the press [79]. At best, we can glean some information from these associations’ own publications. The number of associations created by migrants from Erzindjan was not large (according to the 1913 Patriarchate survey, the total Armenian population of the sub-district was 25,795, and the total number of migrants was 1,952 [80]). The majority of Armenians that migrated overseas from Erzindjan did so only after the Young Turk Revolution.

In 1910, Armenians who had emigrated to the United States from the sub-district’s Gullidje village established a scholastic association. By 1914, this association had 40 members, and had created an endowment of $800. Each year, the interest earned from these funds was sent to the village school. The association also had a chapter in Gullidje itself, whose leader owned a store that sold consumer products. The yearly profits of the store, consisting of 20-25 Ottoman pounds, were also donated to the school [81].

There are also mentions in the press about a scholastic union formed in the American city of Detroit by migrants from the Mahmoudtsik village of Erzindjan. In 1912, members of this organization donated $77 for the renovation of the village school [82].

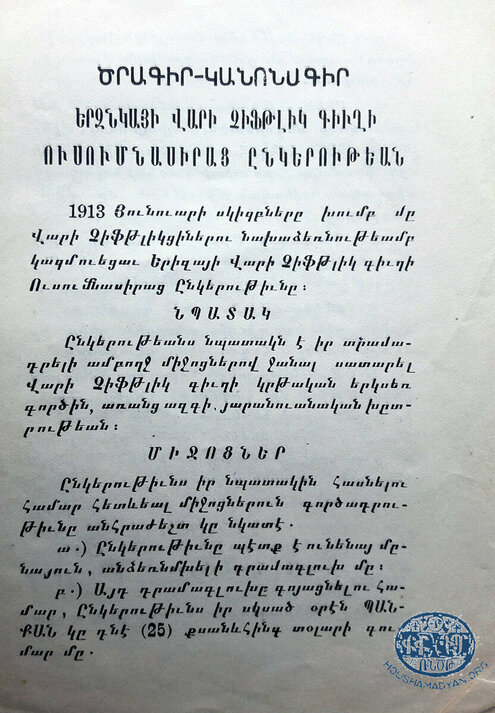

In early January 1913, a group of Armenians who had migrated to the United States from the Vari Chiftlig village established the Scholastic Association of Erzindjan’s Vari Chiftlig Village. The stated mission of the association was to support the co-educational school in the village (“the Association will use all means at its disposal to support co-educational education of children in the village of Vari Chiftlig, without regard to national origin or creed” [83]).

To achieve this goal, the association, from the very first day of its existence, took financial responsibility for the village school and ensured that its needs were met. It appointed a board of directors for the school, and provided children from indigent families with the means to attend classes (tuition fees, costs of textbooks, costs of school supplies, etc. [84])

Members of the association were responsible for raising funds, a portion of which would be added to the association’s endowment, which grew every year. These funds were inaccessible until the total sum reached $500, at which point they would be transferred to the educational union that was meant to be established in Vari Chiftlig [85].

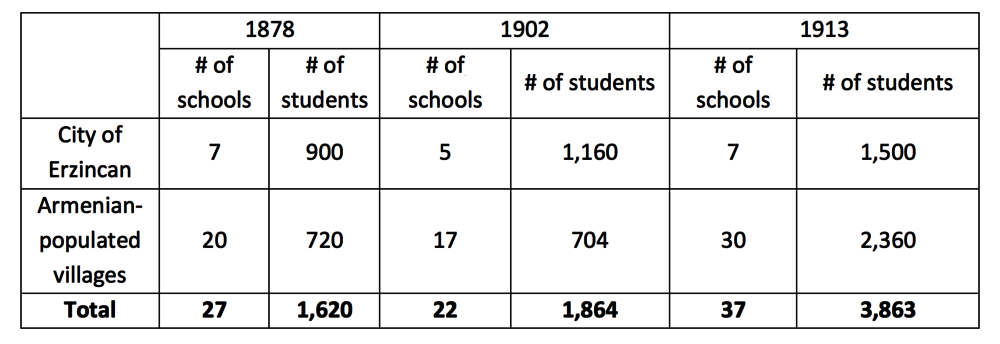

Evidence that education in Erzindjan was experiencing a period of revival prior to the Armenian Genocide is also provided by the periodic Patriarchate surveys. According to the survey of 1913, the sub-district was home to 37 Armenian educational institutions, of which 7 were located in the City of Erzindjan (5 “azkayin” and 2 private), and the other 30 were located in the Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district. The number of pupils enrolled in these educational institutions was approximately 3,860, of whom 1,500 attended the schools in the city, and the other 2,360 attended schools in the villages [86] (information regarding individual villages is provided in the appropriate section of this article). The data from the 1913 survey, when compared to the data from the 1878 and 1902 surveys, shows a sharp increase (more than two-fold) in the number of pupils enrolled in the sub-district’s schools (see Table 1 below).

The Educational Infrastructure of the Protestant Armenian Community of Erzindjan

The number of Armenians in Erzindjan who had converted to Protestantism was not very large – approximately 147 individuals (according to data published by the Ottoman authorities in 1914 [87]); or, alternatively, 500 individuals (in 1902, according to the Armenian Patriarchate [88]). The Armenian Protestants of the sub-district lived almost exclusively in the City of Erzindjan. Most of these Protestant Armenians were not native to Erzindjan. About 20 of these families had moved to Erzindjan from neighboring districts and provinces [89].

The Armenian Protestants of Erzindjan congregated in a two-story house at the western edge of the city’s Armenian neighborhood. This building served not only as a meeting hall and preaching hall, but also as a primary school [90].

The “Azkayin” Neighborhood Schools Operating in the City of Erzindjan on the Eve of the Genocide

The Central School

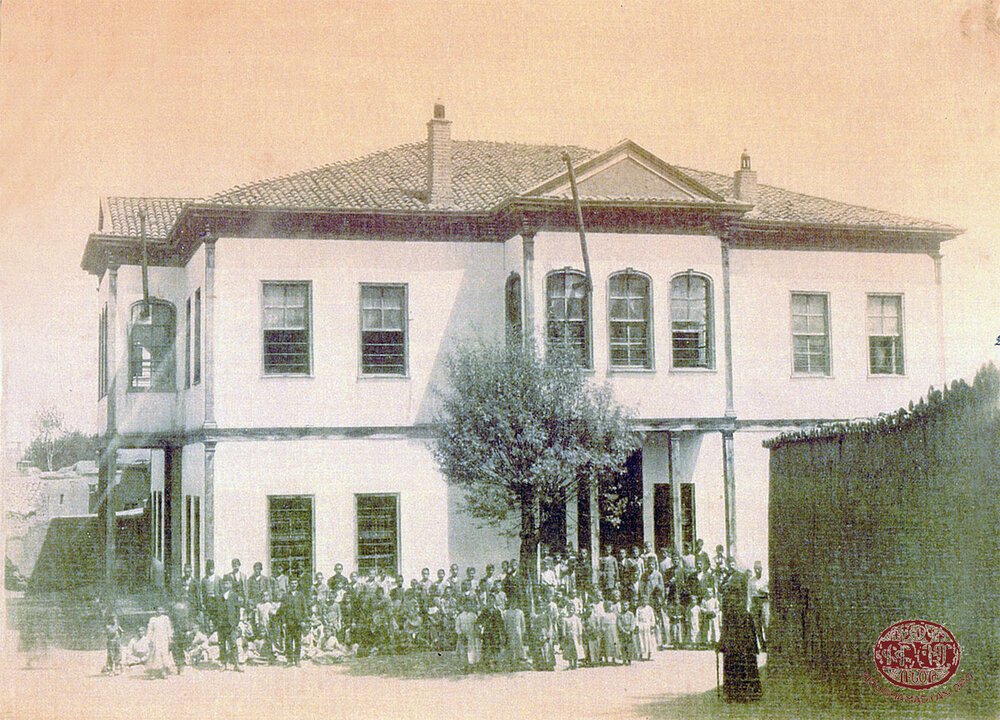

The Central School [91] was the neighborhood school attached to the Holy Trinity Church of Erzindjan. It was housed in a two-story building built in the church square. The first floor housed the primary school and the first and second grades, and the second floor housed the upper grades [92].

The school’s revenue consisted of tuition fees and income from church properties, as well as various donations and fundraisers. Among all the city’s parochial schools, the Central School was the most financially secure. This was due to two main factors – first, The Holy Trinity Church parish was much larger than any of the others in Erzindjan, and second, it owned a large estate, and income from this estate was used to finance the school’s operations [93]. The availability of funds allowed the school’s board of trustees to make it into the best of Erzindjan’s schools, as prestigious as the Association School that operated in the city in the 1880s. The Central School offered a seven-year course of studies, and instruction was provided according to the curriculum developed by the Constantinople National Educational Council [94].

According to reports concerning the 1883-1884 school year, the school had an enrollment of 200 pupils and a faculty of seven teachers [95].

According to the 1902 survey, the school had an enrollment of 280 boys and a faculty of 10 teachers [96].

On the eve of the Genocide, enrollment was between 300 to 350, with a faculty of 10 teachers [97].

In 1914 the principal of the school was Zarmayr Djermagian, who is remembered in his students’ memoirs as a witty, intelligent, serious, profound, and cultivated man, characterized by his strong will and determination. Among the renowned teachers of the school were Dikran Garmirian, Dikran Baghdigian, and Soghomon Rahanian (all three killed during the Genocide) [98].

Among the graduates of the Central School were Avedis Kachperouni, future secretary of the Garin Diocese and deputy supervisor of United Association schools in the Davros region; teachers Vartan Gharchbegian, Nshan Ehramdjian, Garabed Kachperouni, and Nshan Ptigian; Ottoman minister of post Vosgan Mardigian; revolutionary activist Roupen Shishmanian (Keri) [99]; and others.

A teachers’ and students’ organizations operated alongside the school. The local press made particular mention of the Alumni Association, which in 1914 operated a library with about 200 books [100].

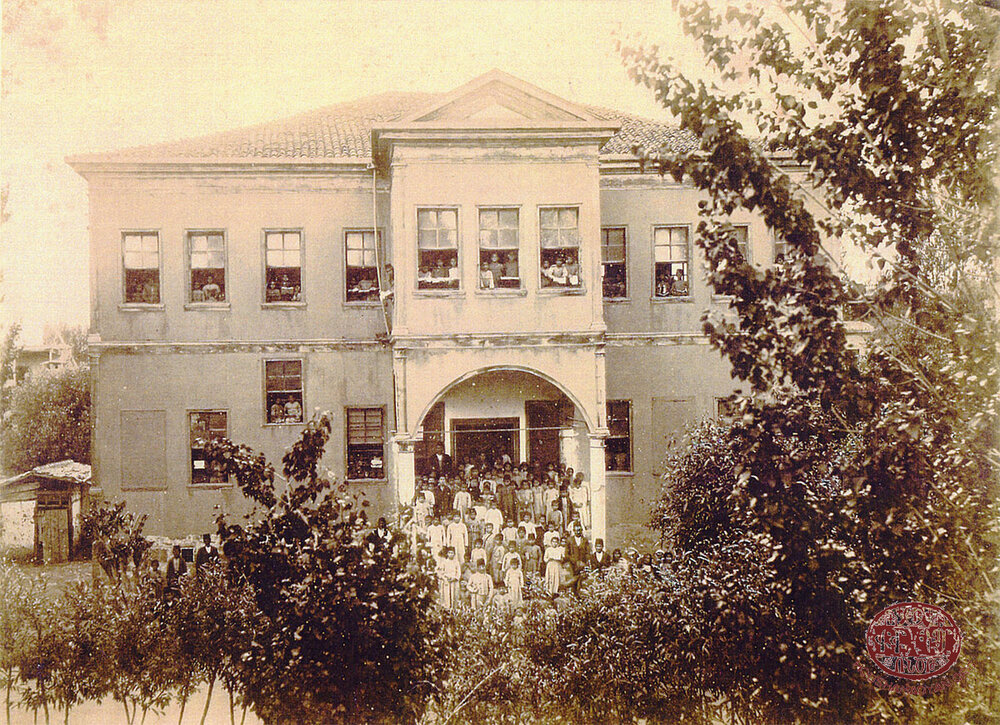

The Yeznigian School

The Yeznigian School was the neighborhood school attached to the Saint Nshan Cathedral. It was the second most prestigious school in Erzindjan after the Central School. The school was housed in a two-story building adjacent to the church, built “in a modern style and using a modern building plan” featuring a new configuration for classrooms and amenities in a “splendid” building. The construction of the building was funded by one of the neighborhood’s wealthy notables [101].

In its early years, Yeznigian was a primary school, but beginning in the 1890s (with some interruptions), it offered upper elementary classes and a six-year course of education.

In 1883-1884, the school had an enrollment of approximately 80 students and a faculty of two teachers [102].

According to the 1902 survey, the school already had an enrollment of 250 boys and a faculty of 10 teachers [103].

On the eve of the Genocide, the school had an enrollment of between 250 and 300 pupils and a faculty of eight teachers [104].

Among the renowned principals of the Yeznigian school was Bedros Srabian. Among its renowned teachers were Mamigon Varjabedian (a native of Keghi, and son of Melkon Djantemirian-Varjabedian), Kourken Papazian, and Nshan Vosgeritchian [105]. Among the graduates of the Yeznigian School was Soghomon Tehlirian [106].

The Aramian School

The Aramian School was the neighborhood school attached to the Saint Sarkis Church. It was housed in a wooden building adjacent to the church. In the 1880s, it was considered to be the second most prestigious school in Erzindjan, second only to the Central School. However, it subsequently experienced a period of decline and was surpassed by the Yeznigian School [107].

According to reports concerning the 1883-1884 school year, the school had an enrollment of 150 students and a faculty of four teachers [108].

According to the 1902 survey, the school had an enrollment of 120 pupils and a faculty of five teachers [109].

On the eve of the Genocide, the school had an enrollment of between 150 and 200 pupils and a faculty of six teachers [110].

The Naregian School

The Naregian School was the neighborhood school attached to the Holy Savior Church. The school was housed in a three-story building partly built of stone. The building was described as “immense and splendid.” As the local community had no need for such a large school, the third floor was almost always vacant. In the 1880s, this floor was rented by the Association School. Between 1897 and 1899, when, for a short period, the neighborhood schools of the city were united under a single banner, the senior classes of the merged school were held in this building [111].

According to reports concerning the 1883-1884 school year, the school had an enrollment of approximately 80 students and a faculty of two teachers [112].

According to the 1902 survey, the school had an enrollment of 160 pupils (100 boys and 60 girls) and a faculty of six teachers [113].

On the eve of the Genocide, the school had an enrollment of between 100 and 150 pupils, and a faculty of four teachers [114].

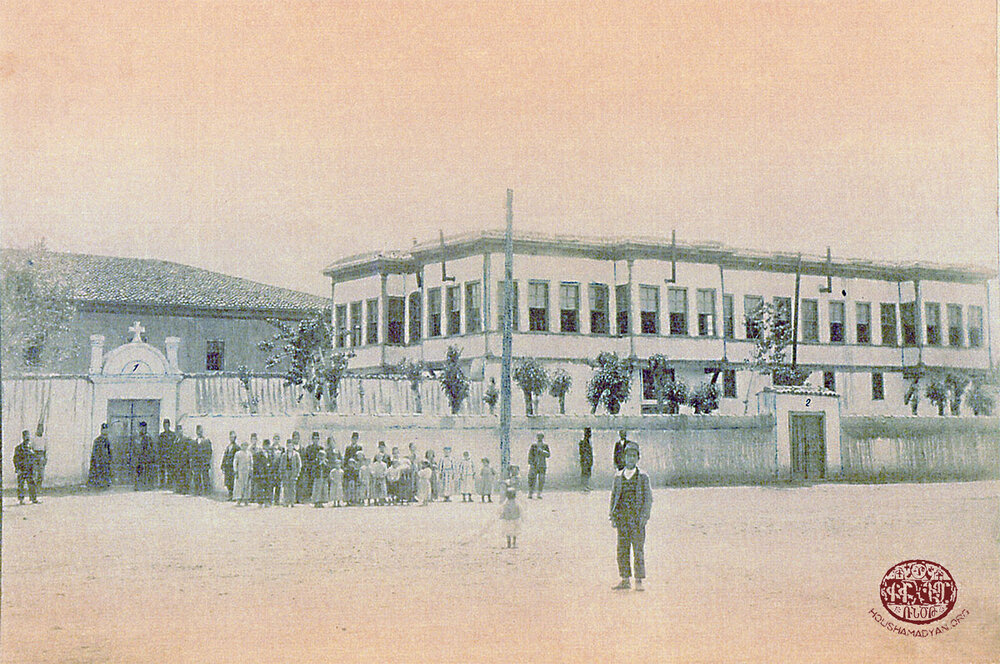

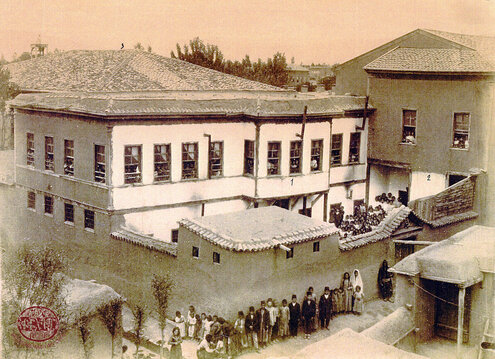

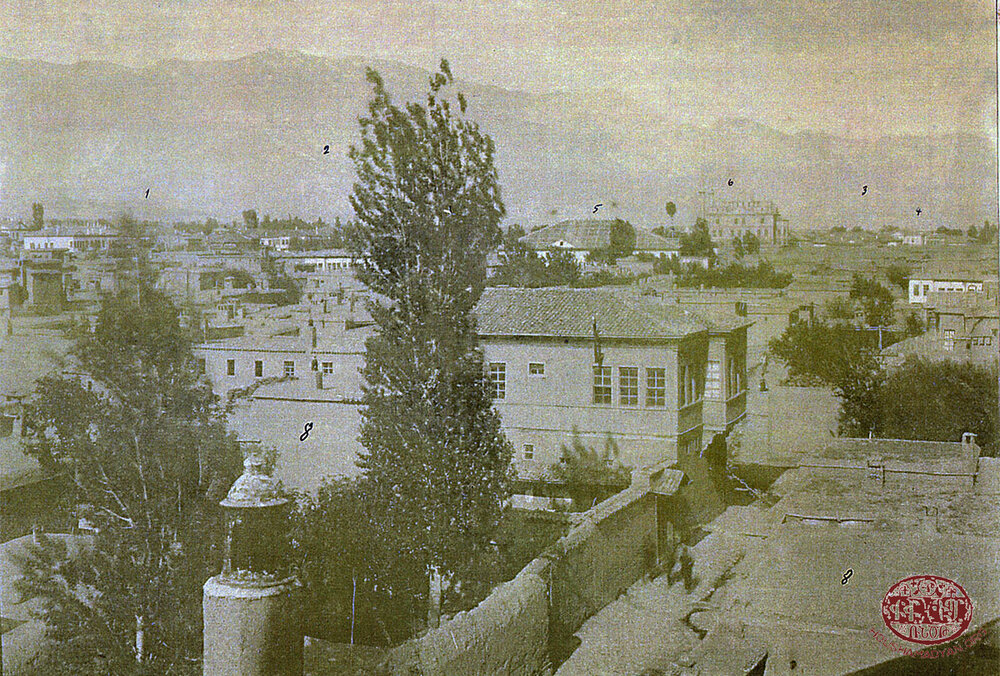

1) The Chrisdinian Girls’ School of Erzindjan (the white building in the center). The structure on the right, featuring the two windows, is the school’s kindergarten. The roof and bell tower of the Saint Sarkis Church are visible behind the white school building.

2) The Saint Sarkis Church. The roof of the Chrisdinian Girls’ School is visible behind it.

(Source: Erzindjan Illustrated Album, Constantinople, 1907, prepared for Bishop Maghakia Ormanian).

The Chrisdinian Girls’ School

The Chrisdinian Girls’ (Maidens’) School was the only regularly operating girls’ school in Erzindjan. It was founded in 1875, thanks to the efforts of Archbishop Krikor Aleatdjian, who served as the prelate of the Erzindjan Diocese from 1874 to 1876. The school was housed in a two-story building located behind the Saint Sarkis Church. The primary school was located on the first floor, while the second floor housed the elementary school [115].

The school had its own board of directors, elected by and answerable to the parochial authorities (“National Board”). The school’s revenues consisted of tuition fees, funds allocated to it by the Patriarchate, the proceeds of various events, and donations [116]. In the 1880s, the school also received financial support from the Patriotic Armenian Society of Constantinople, which founded a chapter in Erzindjan in 1880 [117].

According to reports concerning the 1883-1884 school year, the school had an enrollment of approximately 250 students; and a faculty of one female teacher and two male teachers [118].

According to the 1902 survey, the school had an enrollment of 350 pupils, of whom 330 were girls and 20 were boys. The faculty consisted of 11 teachers (seven female and four male) [119].

On the eve of the Genocide, the school had an enrollment of 350-400 pupils, and a faculty of seven teachers [120].

In 1879, alumnae of the Chrisdinian School founded the Chrisdinian Alumnae Association, whose goal was to help provide school supplies and uniforms to the school’s indigent students [121].

In the 1890s, a kindergarten was established adjacent to the Chrisdinian School, housed in a separate building. The number of kindergarten pupils was 250-300. The kindergarten’s curriculum was based on the “latest, most advanced methods of the Froebelian [122] system,” which was seen as the most progressive pedagogical system of the time [123].

Among the many celebrated teachers and schoolmasters of the Chrisdinian School was Bedros Pogharian, a native of Arapgir by birth.

An interesting note – the yearly examinations of the Chrisdinian School were held in public, and the students of the city’s boys’ schools customarily attended these examinations and listened to the girls as they answered the examiners’ questions. In effect, this was a unique form of bridal visitation, which allowed the youth of Erzindjan to select their potential future spouses [124].

Armenian Schools Operating in the Armenian-Populated Villages of the Erzindjan Sub-district on the Eve of the Genocide

Below, we present information on the schools operating in the individual villages of the Erzindjan Sub-district prior to the Genocide. This information was gleaned from the 1878, 1902, and 1913 surveys conducted by local parochial authorities on behest of the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate, as well as other sources. The villages are listed in Armenian alphabetical order. The Armenian population of each village is provided according to the 1913 Patriarchate census [125].

Aghdjekend (present-day Altınbaşak)

5 households, 45 Armenians.

According to the 1895 survey, the Haigazian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 17 pupils [126]. There is no information regarding the schools operating in the village in later years. K. Surmenian mentions that there was a “pitiful” school operating in the village [127].

Pzvan (present-day Yoğurtlu)

70 households, 430 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Arshagounyats primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 40 pupils [128].

According to the 1902 survey, the Saint Nishan school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 50 students and a faculty of one teacher [129].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 100 pupils [130].

Ptaridj (present-day Bayırbağ)

68 households, 399 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Nersesian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 30 pupils [131].

According to the 1902 survey, the Keshishian co-educational school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 40 pupils (30 boys and 10 girls) and a faculty of one teacher [132].

According to the 1913 survey, the enrollment of the village school was 50 pupils [133]. K. Surmenian mentions that the school had a faculty of two teachers [134].

Ergan (present-day Oğulcuk)

105 households, 852 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Ghevontyants primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 50 pupils [135].

According to an account from the mid-1880s, the village had two operating schools, one “azkayin,” the other private. The private school was administered by Shavarsh Chilasezian, a graduate of the Erzindjan Association School, and an “intelligent and virtuous youth.” The village was described as “studious, hospitable, and quite developed” [136]. The enrollment of the two schools was approximately 40 pupils [137].

According to the 1902 survey, the Ghevontyants co-educational school also operated in the village, with an enrollment of 60 students, consisting of 55 boys and 5 girls [138].

According to the 1913 survey, the enrollment of the village school was 150 pupils [139].

Khntsoreg (present-day Pınarlıkaya)

40 households, 366 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Vartanian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 25 pupils [140].

The 1902 survey does not list any schools operating in the village [141].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 80 pupils [142].

K. Surmenian writes that on the eve of the Genocide, the principal of the Khntsoreg school was appointed by the United Association, which “made a great contribution to the work of teaching our native language to the new generation and ensuring that these half-Kurdish-speaking Armenians did not lose their national identity” [143].

Dzatkegh (present-day Değirmenköy)

78 households, 628 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Torkomian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 60 pupils [144].

According to the 1902 survey, the Mesrovbian boys’ school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 40 students and a faculty of one teacher [145].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 80 pupils [146].

Another source reports that one the eve of the Genocide, the enrollment of the school village was 65 pupils, taught by a faculty of two teachers (accounts vary as to the exact enrollment of schools in specific periods, due to the differences between the nominal enrollment and the number of students actually attending classes) [147].

Garmri (present-day Yeşilçat)

47 households, 315 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Naregian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 20 pupils [148].

Reports concerning 1885 indicate that the village elementary school had an enrollment of 25 pupils. The school only operated during the winter months, as during the summers, the boys were engaged in work in the fields [149].

According to the 1902 survey, a co-educational “azkayin” primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 25 pupils (22 boys and 3 girls) and a faculty of one teacher [150].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school already had an enrollment of 85 pupils [151]. Another source reports that one the eve of the Genocide, the village school has an enrollment of 60 pupils [152].

Geolntsik (present-day Kelines)

39 households, 329 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Torkomian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 20 pupils [153].

The 1902 survey does not list any schools operating in the village [154].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 60 pupils [155].

Gullidje (present-day Güllüce)

60 households, 755 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Vartanants primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 40 pupils [156].

According to the 1902 survey, the Aramian boys’ school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 25 pupils and a faculty of one teacher [157].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school already had an enrollment of 150 pupils [158]. Another source reports that on the eve of the Genocide, the village school had an enrollment of 100 pupils and a faculty of five male and female teachers [159].

Harabedi (present-day Üçkonak)

14 households, 130 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, 10 young boys from Harabedi attended the schools of the City of Erzindjan (the village was located at a distance of about half an hour from the city) [160].

According to the 1913 survey, the village had a school with an enrollment of 30 pupils [161].

Horom Akrag (present-day Tepecik)

36 households, 200 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Haigaznian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 14 pupils [162].

According to the 1902 survey, the Kakigian co-educational school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 40 pupils (30 boys and 10 girls) and a faculty of one teacher [163].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school already had an enrollment of 60 pupils [164].

Gharatoush (present-day Karatuş)

41 households, 235 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Mamigonian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 14 pupils [165].

According to the 1902 survey, the Mesrovbian co-educational school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 25 pupils (20 boys and 5 girls) and a faculty of one teacher [166].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school already had an enrollment of 65 pupils [167].

Gharadigin (present-day Karadeğin)

43 households, 350 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Haigaznian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 20 pupils [168].

The 1902 survey does not list any schools in Gharadigin [169].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school already had an enrollment of 70 pupils [170].

Gharakilise (present-day Altınbaşak)

45 households, 302 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Sisagian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 30 pupils [171].

According to the 1902 survey, the Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Virgin) boys’ school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 15 pupils and a faculty of one teacher [172].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school already had an enrollment of 80 pupils [173]. Another source reports that on the eve of the Genocide, the village school had an enrollment of approximately 50 pupils and a faculty of one teacher [174].

Mahmoudtsik (present-day Mahmutlu)

55 households, 820 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Naregian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 50 pupils [175].

According to the 1902 survey, the Nersesian boys’ school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 50 pupils and a faculty of two teachers [176].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 120 pupils [177].

In 1911, a modern school building was built in the village, housing a library and a hall with a theater stage. The village youth were quite well-educated and greatly valued education. The village produced many teachers who taught both in the City of Erzindjan and in the sub-district’s villages [178].

Medz Akrag (present-day Dörtler)

83 households, 650 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Lousavorchagan primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 60 pupils [179].

According to the 1902 survey, the Aramian co-educational school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 75 pupils (50 boys and 25 girls) and a faculty of two teachers [180].

According to the 1913 survey, the enrollment of the village school was 100 pupils [181]. K. Surmenian writes that on the eve of the Genocide, the school had a faculty of three teachers [182].

Meghoutsig (present-day Yalınca)

304 households, 1,822 Armenians.

Meghoutsig was the largest Armenian-populated village of the Erzindjan Sub-district. According to the 1878 survey, the Hairenik primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 100 pupils [183].

According to the 1902 survey, the Saint Lousavorich boys’ school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 85 pupils and a faculty of two teachers [184].

According to accounts from 1911, the village already had a co-educational school, with an enrollment of 180 pupils (120 boys and 60 girls) and a faculty of five teachers. The school utilized the curriculum developed by the provincial educational council. The village’s newly created local council and board of trustees spared no efforts to fund the school from the village budget, and to ensure that the school received the necessary funds on a regular basis [185].

According to K. Surmelian, in the early 1910s, the school village had an enrollment of 250 pupils and a faculty of four or five teachers [186].

The 1913 survey mentions two schools operating in Meghoutsig, with a combined enrollment of 350 pupils [187]. The schools offered a five-year course of studies, and had a faculty of five teachers [188].

After the 1908 constitutional reforms, on the initiative of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnak Party), an organization called the Progressive Association was formed in the village, with the purpose of organizing educational projects. The efforts of the association resulted in the establishment of a library for adults, as well as a hall that hosted theatrical productions in the winters. in 1911, to raise funds for the construction of a girls’ school, the village youth performed the plays Shoushanig, Sev Hogher, Tebi Azadoutyun, and VartanMamigonian in this hall [189].

Mtni (Mtenni) (present-day Gümüştarla)

120 households, 1,316 Armenians.

Mtni was one of the larger purely Armenian-populated villages of Erzindjan. According to the 1878 survey, the Smpadian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 70 pupils [190].

According to the 1902 survey, the co-educational Saint Ghevontyants school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 100 pupils (80 boys and 20 girls) and a faculty of two teachers [191].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 200 pupils [192].

According to another report concerning the period preceding the Genocide, the village school had an enrollment of 300 pupils and a faculty of three teachers. A library/lecture hall operated adjacent to the school, hosting theatrical productions in the winters [193].

K. Surmenian reports that the people of Mtni were fervently religious and highly valued education, adding that the village’s “magnificent” school had an enrollment of more than 100 pupils and a faculty of three or four teachers [194].

Mollakegh (present-day Mollaköy)

38 households, 280 Armenians.

The 1878 survey does not list any schools operating in the village [195].

According to the 1902 survey, the Holy Virgin co-educational school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 27 pupils (20 boys and 7 girls). The school’s faculty consisted of two teachers [196].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 60 pupils [197].

Shkhli (present-day Uluköy)

23 households, 158 Armenians.

The 1878 survey does not list any schools operating in the village [198].

According to the 1902 survey, an “azkayin” boys’ school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 15 pupils and a faculty of one teacher [199].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 30 pupils [200].

Srbihan (Sourp Ohan) (present-day Kılıçkaya)

31 households, 140 Armenians.

The surveys of 1878 and 1902 do not list any schools operating in this village [201]. According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 50 pupils [202].

Chiftlig Veri/Upper Chiftlig (present-day Hancıçiftliği)

57 households, 336 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Roupinian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 30 pupils [203].

According to the 1902 survey, a boys’ school called Haygaznian operated in the village, with an enrollment of 12 pupils and a faculty of one teacher [204].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 100 pupils [205].

Another account from the eve of the Genocide reports that that village school had an enrollment of 60 pupils and a faculty of two teachers [206]. A small library/reading room also operated adjacent to the school [207].

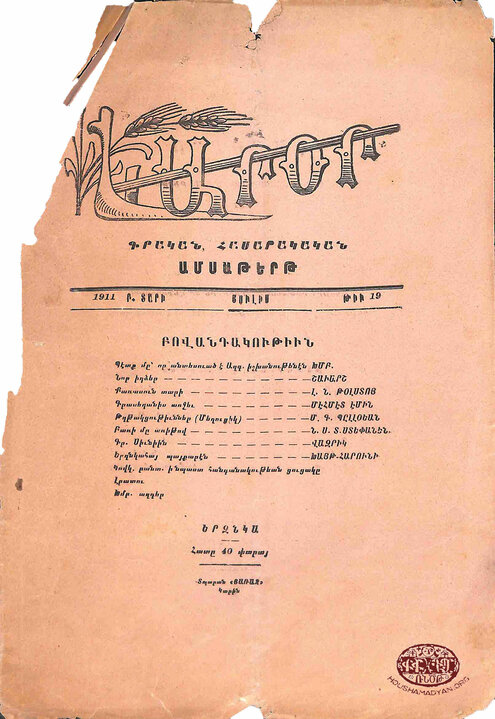

1) The July 1911 issue of Aror Monthly, published in Erzindjan. As this page states, the monthly newspaper was printed by the Harach Printing Press in Erzurum/Garin.

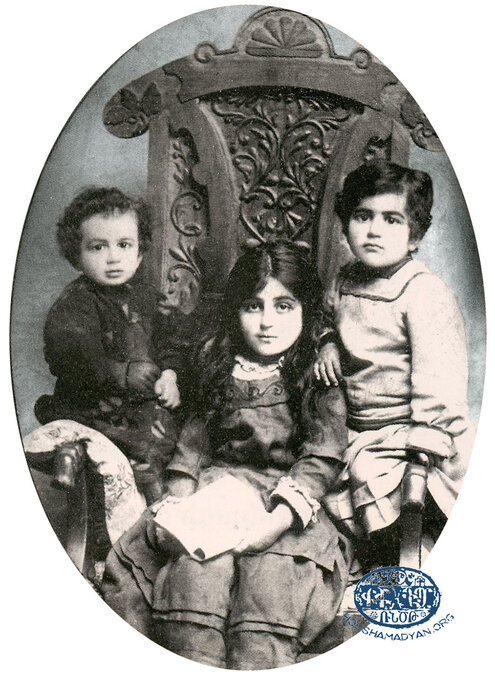

2) Erzindjan, 1913. The children of the Bedigian family (Source: Karnig Sdepanian, Yerzenga/Erzindjan: from Antiquity to Today, Yerevan State University Press, Yerevan, 2005).

Chiftlig Vari/Lower Chiftlig (present-day Ganiefendiçiftliği)

27 households, 229 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Roupinian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 10 pupils (we cannot rule out the possibility that this is the same Roupinian school that operated in Chiftlig Veri, and that the 10 pupils mentioned here were those attending that school from Chiftlig Vari) [208].

According to the 1902 survey, an unnamed “azkayin” school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 20 boys and a faculty of one teacher [209].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 70 pupils [210].

Another account from the eve of the Genocide states that the village school had an enrollment of 40 pupils [211].

Dadjrag (present-day Türkmenoğlu)

33 households, 249 Armenians.

According to the 1878 survey, the Dadjadian primary school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 10 pupils [212].

According to an account from the mid-1880s, the village school had an enrollment of 15 pupils [213].

The 1902 survey does not list any schools operating in Dadjrag [214].

According to the 1913 survey, the village school had an enrollment of 60 pupils [215].

Palanga

14 households, 104 Armenians.

The surveys of 1878 and 1902 do not list any schools operating in this village.

According to the survey of 1913, one school operated in the village, with an enrollment of 30 children [216].

- [1] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga [Erzindjan], Cairo, Sahag-Mesrob Press, 1947, page 13.

- [2] A-To, Vani, Bitlisi yev Ezrurumi Vilayetnere [The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis, and Erzurum], Yerevan, Cultura Press, 1912, page 218.

- [3] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 73.

- [4] Kegham M. Patalian, Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtagan Ngarakire Medz Yegherni Nakhorein. Mas Yerrort: Erzurumi Nahanki Gendronagan yev Arevmdyan Kavarnere yev Erzurum (Garin) yev Yerzenga Kaghaknere [The Demographic and Historical Character of Historical Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide. Part Three: The Central and Western Districts of the Erzurum Province and the Cities of Erzurum (Garin) and Erzindjan, VEM All-Armenian Review, Yerevan, 2015, Year G (13), number 4 (52), October-December, Appendix, page XXX.

- [5] This survey is also known among historians as the 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate Census.

- [6] Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Armeniens dans l’Empire Ottoman a la Veille du Genocide [The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide], Paris, ARHIS, 1992, page 59 and pages 454-455.

- [7] S. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [The Western Armenian World], New York, 1947, page 156.

- [8] K. A. Nazigian, Arevmdahay Mangavarjagan Midkn ou Tbrotse (19rt Tari Sgzpits minchev 19rt Tari 50-60-agan Tvagannere) [Western Armenian Pedagogy and Schooling (from the 19th Century to the 1850s and 1860s)], Yerevan, Louys Press, 1969, page 25.

- [9] Ibid., page 21.

- [10] T. Azadian, Haruramya Hopelyan Bezdjian Mayr Varjarani: Koum Kapou: 1830-1930 [Centenary Jubilee of the Bezdjian Mother School: Koum Kapi: 1830-1930], Constantinople, 1930, page 6.

- [11] Ibid., page 14.

- [12] A. Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario: Deghakragan, Badmagan, yev Azkakragan Ousoumnasiroutyun [History of Armenian Gesaria: A Geographic, Historical, and Demographic Study], Volume 1, Cairo, 1937, page 1095.

- [13] Arevelyan Mamoul, Smyrna, June 15, 1897, number 12, page 429.

- [14] Giragos S. Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner Oughevoroutyan [Mixed Correspondence of Travels], Constantinople, Sareian Press, pages 18-19.

- [15] Ibid.

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] Ibid.

- [18] Ibid., page 18.

- [19] Yeprem V. Boghosian, Badmoutyun Hay Mshagoutayin Engeroutyunnerou [History of Armenian Cultural Associations], Volume 2, Vienna, Mekhitarist Press, 1963, pages 104-105.

- [20] Masis Political, National, Rhetorical, and Economic Review, Constantinople, July 2, 1859, number 388.

- [21] Azkayin Sahmanatroutyun Hayots – Hasdadial 1863 yev Veraknyal [The National Constantinian of Armenians – Confirmed in 1863 and Reinstated], Cairo, Arshalouys Press, 1901, page 33.

- [22] Ibid, pages 41-42.

- [23] L. Chormisian, Hamabadger Arevmdahayots Meg Tarou Badmoutyan [An Overview of a Century of Western Armenian History], Volume A, 1850-1878, Beirut, 1972, pages 525-526.

- [24] Archives of the Yeghishe Charents Museum of Literature and Art (Charents Museum), T. Azadian Fund, Part 3, Sheets 8-9.

- [25] The calculations were performed by the author based on the table provided by the primary source. See the applicable section of the article for figures on individual towns and villages.

- [26] Arevelyan Mamoul, May 1886, pages 230-231.

- [27] Senior Priest Boghos Natanian, Ardosr Hayasdani gam Deghegakir Paloua, Karpertou, Charsandjaki, Jabagh Chouri, yev Yerzengayou Havelvadz Esd Khntranats Azkasirats Khizan Kavari [The Tears of Armenia, or a Survey of Palu, Kharpert, Charsandjak, Jabagh Chour, and Erzindjan, with Additions Requested by the Patriotic People of Khizan Province], Constantinople, 1878, pages 157-158.

- [28] This was the case in, for example, the Pzvan, Gharadigin, Gullidje, Mahmoudtsik, and other villages of the sub-district (S. Amadian, “The Sub-district of Yerzenga. A Description of Armenian Villages,” Arevelyan Mamoul, April 1891, pages 155-159; Arevelyan Mamoul, May 1891, pages 207-210.)

- [29] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 147.

- [30] Ibid., page 128.

- [31] Miatsyal Ungeroutyounk Hayots (1880-1908), Yeramsia Deghegakir, 1098 Okosdos 21-1911 Okosdos 31 [United Association of Armenians (1880-1908), Three-year Report, August 21 1908-August 31, 1911], Constantinople, Nshan Babigian Press, 1911, page 9.

- [32] Ibid., page 11 for the list of schools administered by the organization upon the merger.

- [33] K. V. Srvantsdyants, Toros Aghpar [Brother Toros], Part B, Constantinople, K. Baghdadlian (Aramian) Press, 1885, page 49.

- [34] Masis National and Political Weekly, Constantinople, September 27, 1886, number 3,841, page 139.

- [35] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 154.

- [36] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 117.

- [37] Engeragan Varjaran Yegeghyats: A. Deghegakir Yergamya 1879-1881 Amo [The Association School of Erzindjan: First Two-Year Report, Years 1879-1881], Constantinople, Hovsepa Kavafian Press, 1881, page 10.

- [38] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 117.

- [39] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 120.

- [40] Information on 1879 from K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 130. Information on 1880 and 1881 from Engeragan Varjaran Yegeghyats: A. Deghegakir Yergamya 1879-1881 Amo, pages 5 and 19. Information on 1884 from Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 119.

- [41] Engeragan Varjaran Yegeghyats: A. Deghegakir Yergamya 1879-1881 Amo, page 19. For the list of individuals who donated to the school between 1879 and 1881, see ibid., pages 22-23.

- [42] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 117.

- [43] The school’s educational program by grade – Engeragan Varjaran Yegeghyats: A. Deghegakir Yergamya 1879-1881 Amo, pages 114-115.

- [44] Ibid., pages 15-18.

- [45] Ibid., page 14.

- [46] Ibid.

- [47] Yeprem V. Boghosian, Badmoutyun Hay Mshagoutayin Engeroutyunnerou, pages 114-115.

- [48] We must note that the school’s first principal was Khachig Hovnouni, a native of Divrig, who was described as conscientious and capable, and as an “industrious lecturer.” However, he died only a month after the opening of the school, and the school’s board of trustees was forced to seek another principal.

- [49] Engeragan Varjaran Yegeghyats: A. Deghegakir Yergamya 1879-1881 Amo, page 19.

- [50] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 118.

- [51] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 131.

- [52] Areveleyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 118. Impressions of the school provided by Karekin Srvantsdyants, Mgrdich Portoukalian, Dzerentsi (Hovsep Shishmanian), and Henry Trotter (ambassador of Great Britain in Erzindjan) from Engeragan Varjaran Yegeghyats: A. Deghegakir Yergamya 1879-1881 Amo, pages 25-33.

- [53] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, pages 131-132.

- [54] Ibid., page 132.

- [55] Ibid. As early as March of 1886, the editor of the Arevelyan Mamoul magazine, published in Smryna, sounded the alarm – “We have received disheartening reports on the current state of the Association School of Erzindjan, which is currently facing a financial crisis. We all know that this school is one of the first in Armenia, as confirmed by many prominent Armenians and foreign observers. Naturally, if this school collapses, the cause of education will suffer a great blow. … The founders are doing all they can, and sparing no sacrifices, to avoid the danger of closure. The funding the school receives from the United Association and the tuition fees of the students do not meet the school’s needs. The faculty, after making all possible personal sacrifices and working selflessly, can no longer carry on, and is of a mind to resign and leave. The school’s founders have made several appeals to compatriots to help and support the school, but their appeals have barely been heard.” (Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1886, page 116).

- [56] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 129.

- [57] Ibid.

- [58] Ibid.

- [59] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 53.

- [60] Ibid., page 52.

- [61] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 129.

- [62] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 53.

- [63] Ibid.

- [64] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 141.

- [65] To wit, renowned Erzindjan pedagogue Markar Shavarsh, in his article published in 1897 in the Arevelyan Mamoul magazine of Smyrna, expressed hope that with the unification of the schools, “to receive a higher elementary education would no longer be the preserve of our wealthy compatriots, and the children of poor families, thirsting for knowledge, would benefit. Today, only a small number of them are able to obtain an education, mostly thanks to the pity of this or that kind-hearted sponsor.” (Arevelyan Mamoul, June 15, 1897, number 12, page 428).

- [66] S. Adamian, “Invitation to Erzindjan from the Shores of Honia,” Arevelyan Mamoul, November 1, 1897, number 21, page 713. The author also writes that even before the 1890s, three different attempts were made to unify the educational institutions of Erzindjan, but they had all failed, due to the opposition of the neighborhood councils, which did not want to lose their control of finances.

- [67] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, page 146.

- [68] P. Zorian, “The Current State of Education in Erzindjan,” Arevelyan Mamoul, November 1, 1898, number 21, page 825.

- [69] Barzmen, “The Issue of Unification in Erzindjan,” Arevelyan Mamoul, November 15, 1900, number 22, pages 883-884.

- [70] K. Surmenian, Yerzenga, pages 146-147.

- [71] Vidjagatsouyts Kavaragan Azkayin Varjaranats Tourkyo: Badrasdyal Ousoumnagan Khorhrto Azkayin Getronagan Varchoutyan: Dedr B. Vidjag 1901-1902 Darvo [Report on Armenian National Schools in Turkey: Prepared for the Educational Council of the National Central Executive: Book B, Report on 1901-1902], Istanbul, H. Madteosian Press, 1903, pages 6 and 27.