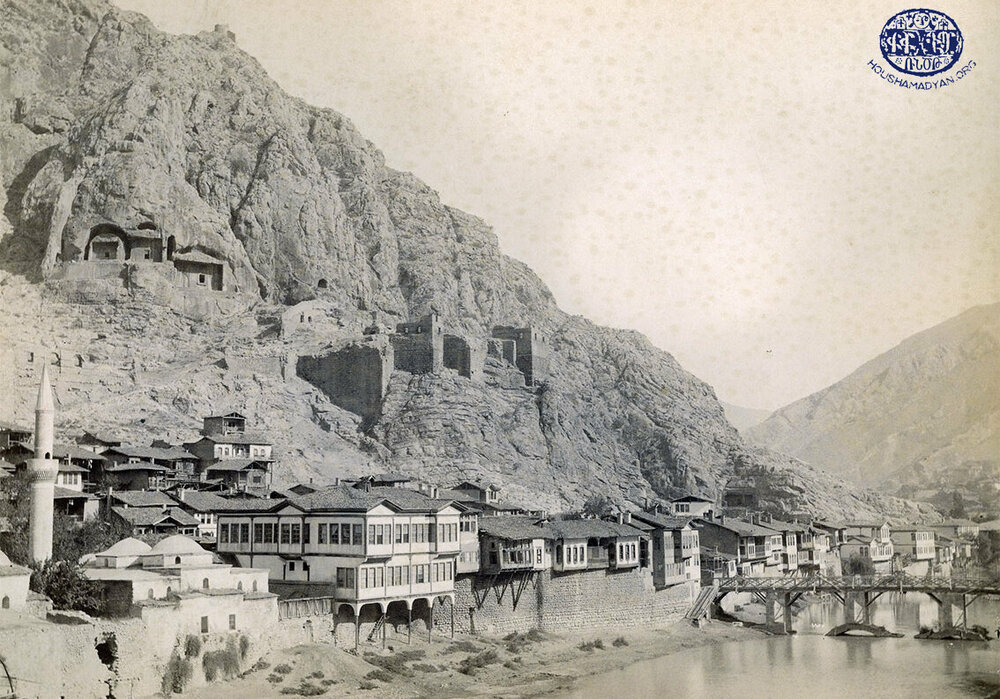

Amasya – Religious Customs

Author: Lory Tashjian, 29/10/2021 (Last modified: 29/10/2021) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The life of Amasya Armenians was rich with religious traditions and customs. Some of these familial and ancestral practices had been inherited from the pagan era. Alongside religious holidays, these practices marked the important stages of life: birth and baptism, betrothal and marriage, and death and burial.

The Armenians of Amasya, faithful to ancestral traditions, steadfastly observed the prescribed celebrations of the various milestones in their lives.

Khoskgab (Engagement)

In Amasya, once a young man reached the age of marriage, his parents and relations would take it upon themselves to find a proper bride for him. Once they settled on a candidate, her parents and family would obviously have to give their consent, too. The negotiations between the two sides would sometimes last for months, even up to a year. While the arrangements were being made, the future groom’s mother would make inquiries about the future bride’s physical traits. She had to be flawless. The people of Amasya bathed at least one a week. To confirm the physical fitness of their potential daughters-in-law, mothers would visit the baths on the same day as they did. If the examination yielded satisfactory results, it was customary to say “paghnikoutyune aghvor e” [“the bathing was satisfactory.”]

The father of the young man, the godfather, and other influential relatives would sound out the girl’s father and family. If they received encouraging signals, a group of them would be formed to visit the girl’s home and ask for her hand. After the preliminary niceties, the future groom’s parents would address their future in-laws: “With the blessing of God and according to the laws and regulations of our church, we have come to ask you to consent to the marriage of [the future groom’s name] to [the future bride’s name].” It was customary for the girl’s parents to initially show reluctance, and protest that their daughter was still too young, that she was not proficient in housework, that the dowry was not yet ready, etc. Eventually, they would consent, and would say: “Let it be as you see fit.” After these words were uttered, the future bride’s mother would go into the adjacent room, where her daughter would be waiting, and instruct her to serve the guests arak, sugar, lokum (Turkish delight), mezze, and coffee. The most senior person in the room, before drinking the arak or liqueur, would express his well wishes and congratulate all involved. Thereafter, all would felicitate each other: “Congratulations! May the Lord give his blessings! May God bring it to a good end! May you always live in light!” With these words, the engagement was considered to have been confirmed, and the two families would agree on a date for the betrothal ceremony.

If the girl’s family refused the suitors, the latter would depart with these words: “May God grant his khayerlu [favor] to both families” [1].

Betrothal

Prior to the second quarter of the 19th century, a betrothal was a very simple ceremony. The groom-to-be’s family would visit the home of the bride-to-be, carrying two trays – one brimming with bunches of flowers, and the other with sweets. A golden ornament would be placed in the center of the latter tray. Men and women would gather in different rooms of the future bride’s home. Traditionally, rings were not exchanged on this occasion.

Over the years, the betrothal ceremony evolved significantly. In more modern times, a jeweler would visit the future bride right after the engagement, then the future groom, and measure their fingers for their rings. The future groom’s family would pay for the future bride’s ring, and vice-versa. The future bride’s family was responsible for the costs and preparations of the betrothal ceremony and celebrations, while the future groom’s family was responsible for the costs of sweets and jewelry. On the eve of the official betrothal ceremony, the future groom’s family would prepare a beautifully adorned tray overflowing with sweets. In the center would be the gold jewelry, arranged around be the future bride’s wedding ring, which would have a silk handkerchief tied to it.

The betrothal ceremony would be held on a Saturday. A procession consisting of the future groom’s family members, of both sexes, would walk to the future bride’s home, where she and her family would await them. The procession would also be carrying the aforementioned tray of sweets and jewelry, including the ring. Upon the guests’ arrival, this tray would be placed in the center of the home’s guestroom, precisely in the center of a table covered with a hand-sewn tablecloth. The future bride would then appear, alongside a recently married, female relative of hers. The godmother would meet the bride at the table, pick up the ring from the tray, and slide it on her finger. She would also hang the jewels from the bride’s neck. In her turn, the future bride would kiss the guests’ hands, starting with her future mother-in-law, the godmother, and then the others. She would be showered with the guests’ well-wishes and felicitations. All the while, young girls would serve food and drinks to the guests.

The betrothal celebration would go on for several hours. The future groom’s family, before taking their leave, would receive a gift – a tray of sweets. In the center of this tray would be the future groom’s ring, with a silk handkerchief tied to it.

In later years, it became customary to present the future groom with a gold watch during the betrothal ceremony. He would wear this watch on his wedding day. It also became customary for the betrothed to slip the rings on each other’s fingers. Once the betrothal ceremony ended, it was no longer improper for the future groom and bride to correspond or to meet in various settings.

The betrothal ceremony would also be attended by the local priest, who would bless the union with his Bahbanich. The two families would then agree on a wedding date [2].

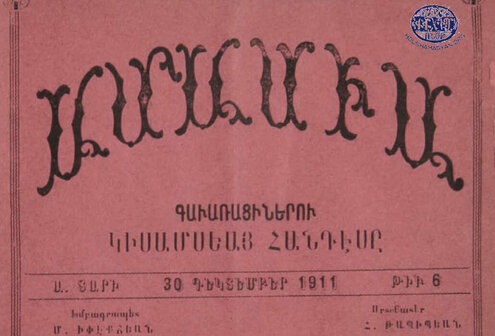

A description of an Amasya betrothal ceremony can be found in a 1911 issue of the newspaper Amasya. The ceremony it describes was performed in a church, after the regular church service, in the presence of the happy couple, their families, close relations, priests, and acolytes. The nshans, or the two rings, were placed on the altar, on white cloth, with silk handkerchiefs tied to them. The main priest officiated the ceremony, blessed the rings, and then, alongside the other priests and acolytes, sang Nshanav Amenahaght [3].

Wedding

Preparations for the wedding ceremony would begin on the Monday of the wedding week. The wife’s dowry would have been prepared in advance. The husband’s family was responsible for the costs of the ceremony, including the wedding attire of both parties. The bride’s veil was provided by the godparents. The invitations were sent out on Wednesday and Thursday. Some invitations were delivered personally by a close friend, such as the godfather. Friday and Saturday were reserved for the festivities. Family, loved ones, and the godparents arrived at the soon-to-be newlyweds’ home, where the revelries lasted long into the night. These guests would spend these nights in the newlyweds’ home. Prior to the popularization of written wedding invitations, the people of Amasya practiced a tradition called tzendouk. Members of the families would personally visit relatives and friends to invite them to the ceremony. Tzendouk can roughly be translated into “give a call.” In Amasya, tzenel was the equivalent of the Armenian tsaynel, which translates into “to call” or “to invite” [4].

Historically, wedding invitations were handwritten. In later years, when printing presses began operating in Amasya, printed invitations became the norm.

Until Monday evening, separate celebrations would be held in the bride’s and groom’s homes. Family members would send lamb, baklava, and other delicacies. It was also customary for the bride-to be to receive gifts of gold. Presents given on a wedding or the birth of a child were called teore/töre.

The two sexes would celebrate together but would not mix. On the men’s side, a long table, consisting of two planks, rising to 45 centimeters from the floor, would be set. The attendees would sit cross-legged around this improvised table, which would be covered with a tablecloth and a long towel. This towel was called dolama peshgir, and was sewn in a checkered pattern, with white and blue fabric. It was unique to Amasya, and each Armenian household in the town owned one. A similar table would be set on the women’s side of the hall. A separate table would be reserved for the singing musicians. In the more distant past, girls and women would celebrate in a different room, separated from the men.

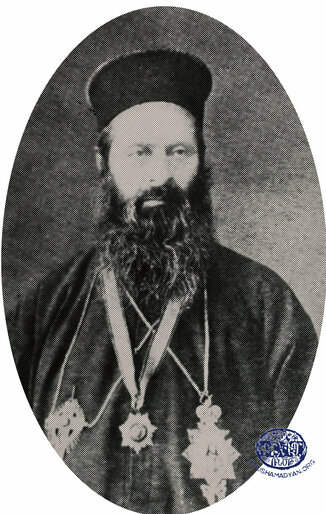

1) Bishop Hovhannes Yetesian, Prelate of the Amasya-Marzvan Diocese from 1868 to 1877. He died in 1884 and was buried in Amasya.

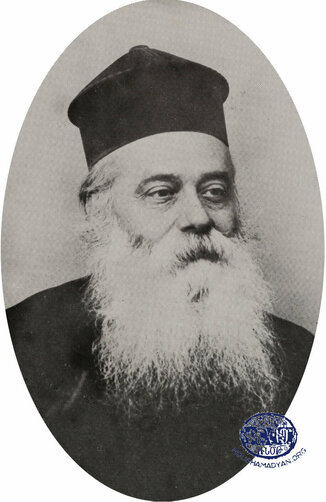

2) Father Diradorian, a priest from Amasya, who served as a cleric in Samsun.

3) Father Sahag Odabashian. In 1905, he was appointed interim prelate of the Amasya Diocese.

(Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice).

The actual wedding ceremonies would begin on Saturday, in the groom’s home. The first event was called ergenler. One of the bachelors invited to the wedding would be chosen as the ergen bash, and he would assume the role of the tamada (toastmaster). He would be responsible for overseeing the festivities. The groom would tie a keshan peshdimbal (Keşan peştemali) around the ergen bash’s waist. This was a silk belt, made in Keshan. In his turn, the ergen bash would select a group of young men as his designated assistants and would tie locally made aprons around their waists.

The first dishes and drinks to be served were sini bourma beoreg, other pastries, mezze, and arak. The guests would clink their glasses – an act called tokha – and toast the bachelors, wishing them a swift marriage. Then, the guests would be served meat with zerdeli (apricots), pacha, and various pickles.Meanwhile, the ghouzou/kouzi (lamb) would be roasting in the oven, stuffed with pilaf. Once ready, this roasted lamb, garnished with parsley in its mouth, would be brought to the table on a tray. The toastmaster would cut the meat and serve it to the guests. The first portions would be reserve for the godfather and godmother.

The ergen bashi would also be the first to drink the wine. He would pour a glass and toast the godfather and godmother. He would then sing a song dedicated to a revolutionary hero. This would often be Rafael Badganian’s poem, which had been turned into a song:

Te im alevor herks sevnayin,

Ouyj indz yed kar, gdridj tarnayi,

Njuyk tsi nsdadz, bekhers voloradz,

Tserks tour aradz razmatashd g’ertayi. [5]

[If my grizzled hair were to turn black,

If my strength returned, and I became a warrior,

Astride a steed, with my mustaches rolled,

Sword in hand, I would make for the battlefield.]

The wine would flow generously; the singing, music, and dancing would begin; and a joyful and celebratory mood would dominate. Celebrations would also be held in the future bride’s home, but they would be less exuberant.

On Saturday morning, the godmother would take the bride to the baths. They would be accompanied by other girls who were of marriage age. Later that evening, it was the turn of the godfather to take the groom and the other young man to bathe. This latter event was called pesapaghnik and was a joyful occasion.

On Saturday night, the hina khaghtsnel [playing with the henna] ceremony would be held. The henna would be poured into a tub, and many of the guests would dance while carrying this tub above their heads. The little finger of the pesakhbar would be dipped into the henna, and the rest of it would be sent to the future bride’s home, where she and many of her companions would also dip their little fingers into it. In earlier times, it was also customary to paint various patterns in henna on the bride’s heel, toes, and hands. We must note that the pesakhbar played an important role throughout the wedding ceremonies, and he was not the groom’s brother. He was a young man who accompanied and assisted the groom throughout the wedding. He was often the godfather’s son.

On Sunday morning, the bridal party’s wedding attire would be sent from the groom’s home to the bride’s, alongside the empty dowry chest, which would usually be made of walnut wood. The key to the chest would be entrusted to a young boy, who would only relinquish it to the bride upon receiving a gift from her. The women and girls would then carefully pack the bride’s dowry into the chest.

Another ceremony held on Sunday was called pesa trash. A barber would arrive to the groom’s home and shave the godfather first, then the groom, and then any of the other guests who wished to be shaved. Musicians would play during this ritual, with a bard singing the praises of each of the men being shaved. The men would pay the musicians by placing money on the santur (stringed instrument of the hammered dulcimer).

On Sunday evening, after regular church services, the ceremony of the blessing of the dowry and the wedding attire would be conducted.

After the festivities on Sunday night, the ceremony of dressing the groom would begin, and would last until late into the night. The groom would be in his undergarments. His loved ones and friends would take turns and dress him with one item of clothing each. The attendees would exclaim “May God grace it with his blessings!” every time an item of clothing was donned by the groom [6].

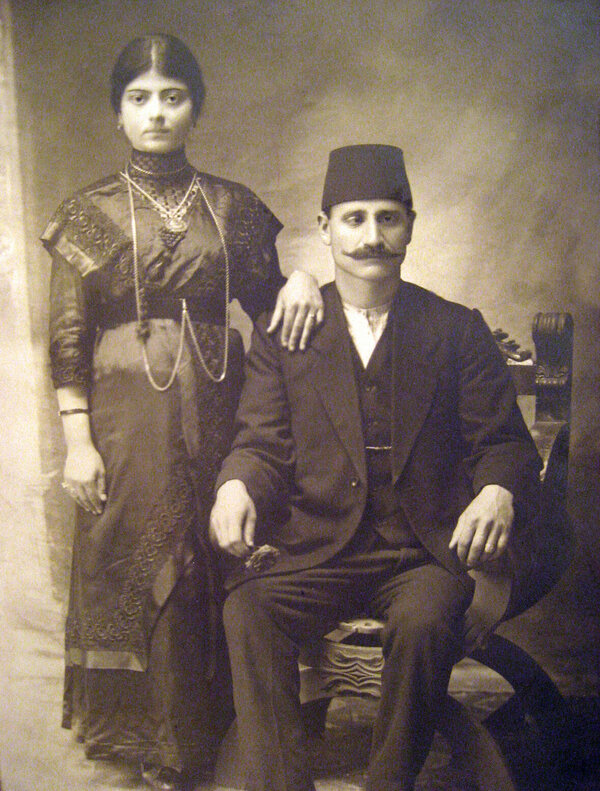

Until the first quarter of the 19th century, the attire of an Armenian groom from Amasya consisted of a tasseled fez, a meles (silk) shirt, a yelek (sleeveless vest), and a starched collar. Over the yelek, grooms would wear the mintan or mitan, a coat made of blue wool. Grooms would also wear blue shalvars (baggy trousers), socks, and shoes that were called labdjin galosh. Around their necks, they would hang the saat keoset, a gold watch with a chain. This attire evolved over the years and gradually became westernized. Eventually, the only traditional item that was kept was the tasseled fez [7].

As for brides, until the middle of the 19th century, they would wear a simple, silk dress adorned with patterns embroidered with silver thread. They would also wear an embroidered belt around their waists, with a silver buckle. Over the dress, they would wear a coat also embroidered with silver thread. The entire attire was called the gaba. On their heads, brides would wear a wooden hat that resembled a small fez, which craftsmen would make by carving out light wood. This hat, called a dingil, would be wrapped in colorful silk. Over this hat, brides would wear a veil the covered their faces and backs. On their feet, they would wear socks and silk shoes that resembled slippers. From head to food, brides would be concealed by a simple and densely woven silk veil, which was usually a gift from the godmother. The bride’s brother would tie the belt around her waist, repeating three times: “One like you, two like me.” This was a benediction, hoping that the bride would have two sons for each daughter she had. Dressing the bride was the responsibility of the godmother.

Beginning in the middle of the 19th century, like the wedding attire of grooms, the attire of brides underwent great changes under the influence of western trends. The gaba was replaced by a dress called bindallu (one thousand branches), made of blue or red velvet and embroidered with patterns sewn in silver thread. The bindallu was a full dress, covering the bride from head to toe. Over this dress, brides would wear a coat made of the same material, and around their waists they would wear a velvet belt. On their heads, instead of the dingils, brides began wearing a needle-embroidered silk veil. By the end of the 19th century, Armenian brides in Amasya had almost completely adopted the western wedding dress [8].

Once both the bride and groom were dressed, two hours after midnight, preparations would begin for the harsnar [carrying off the bride] ceremony. A procession would be formed, led by a youth holding a burning torch of resinous branches. He would be followed by the godfather, members of the family, and other men, in their turn followed by the women, children, and the musicians. This procession’s objective was to “carry off” the bride from her home and take her to church for the wedding ceremony. Upon arrival at the home, the procession would find the door shut. They would knock several times but would receive no answer. Then, they would promise a bribe to the member of the bride’s family guarding the door. The latter would immediately open the door, and the groom’s procession would pour in [9].

Customarily, young men from the groom’s side would attempt to steal a turkey or a few hens from the bride’s family’s henhouse, while young men from the bride’s side would attempt to thwart these attempts. In the end, the groom’s side would succeed in stealing at least one animal. They would tie the turkey’s or hens’ feet to a long stake, and two of them would hoist the ends of the stake on their shoulders. They would then light a wax candle and wait for the procession to join them in the street outside.

After a few hours spent in the bride’s home, the time would come to head to church. The bride’s family would not usually attend the wedding ceremony. But they would send representatives, two men and two women, who would be present throughout. These were called harsnbahs. As the groom, alongside the bride, left the house, her mother would shove two small and large cakes under his and the pesakhbar’s arms. The bride’s representatives would walk ahead of the groom’s procession. At the very head of the group would walk two young girls holding wax candles. These would be followed by the bride and the godmother, the groom’s mother, the harsnbah ladies, as well as all the women and girls on the groom’s side, all holding lighted candles. Behind them would come the groom’s procession, led by the groom, the pesakhbar, the groom’s father, and the godfather. All other guests, as well as the musicians, would follow them. It is said that in earlier times, the bride would be seated on a steed and would be escorted to church by three brave men, one of them holding the horse’s reins.

On the way from the bride’s home to the church, the musicians accompanying the procession would play music and sing wedding songs, such as this one (see the English translations in the righ column):

Yegan touru shukhshukhtsoutsin, Mi lar, mayrig! | They came and banged on the door, |

The following was a well-known wedding song in Turkish:

Duz ğaçını duzsuz koyan, | The saltshaker, empty of salt, |

The procession would enter the church. The bride, groom, and godfather would stand at the main altar. The ceremony of marriage would be performed. Afterwards, the bride and groom would leave the church together, the procession would re-form, and the crowd would head to the groom’s home. A sheep or lamb would be slaughtered on the threshold, and the new bride would step in the blood before entering the main hall alongside the candle-bearing girls. These candles would be put out and stored, to be used in the future during the baptismal ceremony of the couple’s first child. The men would then head to a larger room. The groom would wait in a corner of the room until all the others took their seats, after which he would go around the room and kiss the hands of his elders, receiving their benedictions in exchange. He would shake hands with those younger than him. Eventually, after receiving the godfather’s permission, he would take his seat. Similarly, the bride, in the room reserved for the women, would wait for all to take their seats, and then make the rounds and kiss the guests’ hands. She would also receive her teore, the name given to the jewelry she received to mark the occasion [11]. This would generally consist of gold necklaces and chains, as well as pearl and diamond earrings [12].

Meanwhile, the women in the room would be offered arak, baklava, qurabiya, sweets, and cake. The godmother, with another young woman, would lead the new bride to the men’s hall, where she would kiss the hands of the godfather, her new father-in-law, and then the rest of the men, receiving their blessings in exchange [13].

On the Monday after the wedding, the men would leave for work, promising to return in the evening and attend the continuing festivities. The groom would now be left in the men’s hall with just his family and a few close relatives. In the women’s hall, the celebrations would continue with singing, music, and dancing.

On Monday evening, the festivities would resume. The tables would be set, and the toastmaster would present the day’s meal, which was usually an oven-roasted lamb stuffed with pilaf. This feast would continue until ten or eleven o’clock at night, in the presence of musicians. Thereafter, the guests would take their leave, and even the home’s residents would spend that night with relatives. The only ones allowed to stay in the home that night were the bride and groom, the godmother, the groom’s mother, another lady, and a few children.

The groom would enter the nuptial chamber, alone. It was customary for the godmother, sometimes accompanied by the bride’s new mother-in law, to gently coax the bride to enter the room and join her new husband.

On Tuesday morning, the day after the night of consummation, the godmother would awaken the newlyweds and check the nuptial chamber. If she found everything in order, she would lead the new couple to the hall, where a small number of relatives would be gathered. For this occasion, the family would prepare halva made with flour and plenty of oil. The guests gathered around the table would clink their glasses of arak and congratulate each other. A woman would be chosen to take the good news of the consummation to the bride’s parents. She would also take a package of sweets with her as a gift.

This is how the married couple’s new life would begin in the groom’s home. The custom in Amasya was for several generations to live under one roof. Sons brought their brides and raised their families in their parental home. Only when there was no room left would a son establish a new residence. There were occasions when a groom moved into the bride’s parental home. Such a groom was called a doun pesa [house groom]. This was not a popular tradition, and often resulted in endless disputes between the grooms and their in-laws. In fact, a popular adage in Amasya went, “Doun pesa, shoun pesa” [“House groom, dog groom”] [14].

Five days after the wedding, on Friday, the bride’s mother-in-law would send invitations to all female in-laws, the godmother, and female relations and friends to join her on a visit to the baths. On Saturday morning, the entire group, alongside their children, and accompanied by the bride, would enter the baths. This ceremony too, was part of Amasya’s wedding rituals, and was called harsnapaghnik. A special area would be reserved for the bride and her companions, which would not be closed-off like the other stalls. There would be a platform, rising to about a meter above the floor, upon which the family would sit, visible to all in the baths. To bathe the new bride was an honor, and therefore every female relative attempted to participate in this ceremony. At noon, after the bathing, a sheet would be spread on the floor, and the bride and the other young women would serve the food they had brought with them.

After bathing the bride, her companions would place a wreath of woven ribbons on her head, with silver chains dangling from it. The bride would kiss the hands of her companions, leave the bathing stall, and walk into a separate room where a curtain would be held for her to protect her privacy. She would put on her undergarments, after which the screen would be taken down, and the ceremony of dressing the bride, again in full view to all who were present in the establishment, would begin. The bride would be dressed in the most valuable clothing in her dowry, and she would then stand in the corner of the baths, so that she could be seen by all. “May God watch over her, protect her from the evil eye,” would say the Armenian women, while the Turkish women would join in with “Mashallah, Allah sahabuna baghshlasun” (Maşallah, Allah sahibine bağışlasın). This marked the end of the ceremony.

On the Sunday after the wedding, the groom’s mother, alongside her relatives, would take the new bride to church. On the Sunday two weeks after the wedding, they would also be joined by the bride’s parents. After the church service, the groom’s parents, bride, and groom would lunch at the home of the bride’s parents. In the evening, the groom’s parents would leave, but the bride and groom would remain behind. This was known as the “dzerk baknel” [“kissing of the hands”] ceremony [15].

Birth and Dgharouk

In Amasya, the term dgharouk referred to the baptism of a child and the celebrations that were held to mark this occasion. The guests who attended this event were usually women, and included the godmother, midwife, and female relatives, alongside their daughters and children.

The baptism ceremony was performed on the Sunday closest to eight days after the birth of the child. It is notable that most of the participants in this ceremony were women. That Sunday, the midwife, godmother, and other relatives would gather in the child’s home, then take the child to church. The mother would stay at home. At church, the priest would perform the baptismal ceremony, after which the child would be wrapped in cloth and carried by the godfather to the main altar, where the day’s preaching priest would be standing. The latter would place a small crumb of the host in the infant’s mouth. In this way, the infant would receive his/her first communion. The godfather would then walk back to the godmother and hand the infant to her. The family, alongside the priest, would return home, where the dgharouk celebrations would continue [16].

Another source states that in Amasya, the dgharouk celebrations would be held on the day after the baptism ceremony. After the arrival of the female guests, the newborn would be brought out in the crib. The guests would kiss his/her forehead, which would be anointed with holy water, and each would place a gift beside the infant. These gifts would usually be gold or silver coins, yazmas, socks, and undergarments. According to the same source, the dgharouk ceremony was generally held for a family’s first-born [17].

The dgharouk ceremony would last until noon. At that point, the men would leave, and only women, girls, and children would remain. Different types of confectionaries would be served, and the adults would enjoy various spirits. In the afternoon, it was time to enjoy a special cheoreg called cheoreg shougayi [18], a culinary delicacy unique to Amasya and a staple of local wedding and baptism celebrations. It was made with thin, ridged dough, and a stuffing of walnuts, cinnamon, and powdered cloves.

For forty days after the baby’s birth, the mother and child were not allowed to sleep in the same room without supervision. The mother-in-law, or another elderly female relative, would usually share the room with them. These women’s task was to keep vigil and make sure that the al did not enter the room through the window, lest it strangle the mother and baby or kidnap the baby and replace him/her with another. If the mother and baby were forced to be alone in a room, a man’s hat would be placed near the mother’s pillow, or a needle would be thrust into the blanket, in order to ward off the evil spirit [19]. The al was this evil spirit. This belief in evil spirits preying on newborns and their mothers had its origins in the fact that in Amasya, in those years, it was common for new mothers and newborns to contracts various illnesses. And so, if the mother or newborn died soon after birth, the people of Amasya would say that the “Al had struck them” [20]. Another common saying in Amasya was: “For forty days and forty nights after birth, a hoe and a shovel must be placed under a mother’s pillow.” The hoe and shovel were gravedigger’s tools. They were tangible reminders of the fact that for the first forty days after birth, death constantly stalked the mother and newborn.

The day after the dgharouk, the ceremony of dipping the infant in holy water would take place. The midwife would wash the child, set him/her down in the crib, then pile about four kilograms of cotton nearby. She would then pick up the infant and carefully roll him/her around in the cotton. This action would be repeated three times, and each time, the midwife would recite the same words: “Whether you climb up a tree, up a hill, or up a mountain; if you fall, may you always fall on a tay.” A tay was a foal. This was a blessing, hoping that whatever misfortune befell the child, he/she would always remain healthy [21].

New mothers in Amasya usually observed a karasounk (forty days) after birth. For at least 40 days after giving birth (and sometimes even longer, up to 60 days), they would not leave the home. On the fortieth day, mother and child would be dressed in their finest and visit the church. There, after the service, the priest would perform a special reading for the two. Afterwards, the new mother would always lunch at a relative’s home [22].

In Amasya, newborns were nursed on mother’s milk for at least one year. Sometimes, infants were nursed for up to three years. If the mother could no longer nurse, or if she fell ill, she was replaced by a wet nurse, who was called a djuzgan [23]. Mothers who were able to lactate normally but chose to entrust their child to a wet nurse were severely scorned [24].

The midwives of Amasya were usually elderly women, and they would supervise the entire course of a woman’s pregnancy. After the reinstatement of the Ottoman Constitution (1908), a midwife with a certificate from the Istanbul Medical Institute, Aghavni Vosgerichian, returned to her native Amasya and was licensed by the local authorities as the city’s official midwife. Her services were usually sought by families that were considered more progressive and educated. Traditional midwives continued serving the city’s Armenians [25].

The mothers of Amasya would bathe their newborns in hot water every day until the 40th day after birth. While bathing their children, it was customary for mothers to hold them by their ankles, upside-down, and to recite the following: “Shalge mesig, totve chourig” [“Carry a mesig, shake off the water”]. It is unclear what they meant by mesig. Possibly, it’s an adulteration of the word misig (meat/flesh), comparing the newborn to a hunk of flesh [26].

The people of Amasya had a unique idiom that had become a local adage. If an enterprise failed, they would say that it “hadn’t come out of the water.” This idiom’s origin was the following anecdote: one day, six children were to be baptized together at the Holy Virgin Church of the city’s Savayid neighborhood. When the priest plunged the first of the infants into the water, the latter died immediately, killed by the extreme heat of the water. The priest reacted by saying, “This one didn’t come out of the water. Bring me another” [27].

Below are examples of lullabies sung by the Armenian mothers of Amasya (see the English translations in the right column):

Nanni anem kounu dane, Mahlen tskem shounu dane, Horkouyrn arne dounu dane, Tatigneroun hina tne. Nannig anem vor medztsnem Karneroun geolu loktsnem, Meghrov khaymakh gertsnem, Baghoug chourer al khmtsnem. Bar-bar, dapag kar, Yegour dayin yaylan dar, Bzdig e chem i dar, Yerp medzna ne yergou dar. Bar anem djor anem Gaban garem chor anem, Zadig ka ne nor anem Yes as dghan inch anem. Oror unem vor knana, Anoush kounerou dirana, Amen tsaverou timana. | I will rock you, sleep will take you, |

The mothers of Amasya also sang Turkish lullabies to their babies, including this one:

Nenni nenni nesdesi,

Gilabdonın desdesi,

Oğlum uyku hastesi,

Nenni deyim uyusun,

Uyusun de böyüsün,

Çıksın beşiktan nürüsün. [28]

Death and Funeral

The priest would be called to the deathbed to recite the Narek and administer communion. Aside from these traditional rites, there was another, more unique custom practiced in Amasya. There were elderly women in the town whose duty it was to sit at the head of the deathbed and murmur prayers over the sick person. They would also yawn repeatedly while performing their task. If they yawned excessively, it meant that the illness was not terminal and that the sick person would soon be cured.

These women also performed the ceremony of casting the ghourshou [lead] [29]. A quantity of lead or wax would be melted in a pan, and then poured into a bowl of water [30]. The melted substance would take on different shapes in the cold water, and these women’s task was to interpret these shapes and make predictions regarding the sick person’s fate [31].

Once the sick person died, one of his/her loved ones would close his/her eyes, then arrange his/her arms and legs. The arms would be arranged in the shape of a cross across the chest.

The devout Armenians of Amasya, especially the women and peasants, had a practice of washing the corpses of their loved ones before the funeral. This was done to ensure that the deceased left this world in a state of purity. Those performing this ceremony they would place a lighted candle, in a candelabra, behind the deceased’s head. It was also customary to place, in the deceased’s palm, a piece of wax from a candle that had been lit at the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem. Generally, all married women had pieces of this wax in their marital dowry. After being cleaned, the deceased would be wrapped in white cloth.

The deceased would be placed in a coffin, or as the people of Amasya called it, a gatakhk. The mourners would then form a procession and make their way to the funeral. The procession would consist exclusively of men. One of them would have a carpet or a rug from the deceased’s home draped over his shoulder. This item would be donated to the church after the ceremony. After the short church ceremony, the coffin would be carried to the cemetery. The priest would bless the dirt, which would be presented to him in a shovel. Afterwards, the mourners would kiss the priest’s cross and wash their faces and hands with the water from the cemetery’s spring. A modest funeral meal would be served near the external doors of the church. The mourners would drink arak and eat kesme sheker and lokum.

After the death of a loved one, women would wear black for forty days, and men would refrain from shaving for the same span of time. Sometimes, men in bereavement would not shave for up to three or six months [32].

- [1] Kapriel H. Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo [Memory Book of Pontic Amasya], Saint Lazarus Island (Venice), 1966, p. 892.

- [2] Ibid., p. 893.

- [3] Arkam Knouni, “Hay Kavaragan Parker yev Sovorutyunner – Nshandouku” [“Armenian Provincial Traditions and Customs – Betrothal”], Amasya, year 1, 15 December 1911, number 5, pp. 71-73.

- [4] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 895.

- [5] Ibid., p. 896.

- [6] Ibid., p. 897.

- [7] Ibid., p. 890.

- [8] Ibid., pp. 886-887.

- [9] Ibid., p. 897.

- [10] Ibid., p. 898.

- [11] Ibid.

- [12] Ibid., p. 884.

- [13] Ibid., p. 899.

- [14] Ibid., p. 900.

- [15] Ibid., p. 902.

- [16] Ibid., pp. 902-903.

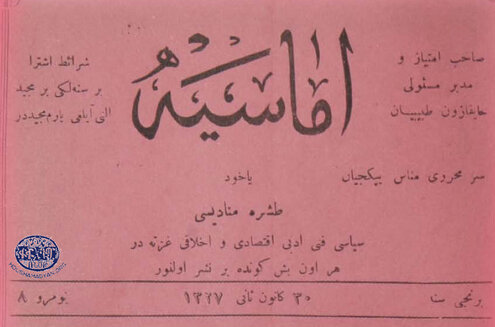

- [17] Mgrdich Kechedjian, “Amasyatsi Hay Ginu” [“The Armenian Woman of Amasya”], Manzoumeyi Efikyar, year 49, 17/30 January 1907, number 1711, Istanbul.

- [18] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 879.

- [19] Ibid., p. 903; Mgrdich Kechedjian, “Amasyatsi Hay Ginu.”

- [20] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 923.

- [21] Ibid., p. 904.

- [22] Mgrdich Kechedjian, “Amasyatsi Hay Ginu.”

- [23] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 921.

- [24] Mgrdich Kechedjian, “Amasyatsi Hay Ginu.”

- [25] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 921.

- [26] Mgrdich Kechedjian, “Amasyatsi Hay Ginu.”

- [27] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 903.

- [28] Mgrdich Kechedjian, “Amasyatsi Hay Ginu.”

- [29] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 918.

- [30] Ibid., p. 921.

- [31] Ibid., p. 918.

- [32] Ibid., p. 919.