Van - Monasteries and Churches of Timar

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 26/10/18 (Last modified 26/10/18) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Monasteries of Timar (nahiye)

The Saint Garabed Monastery of Gdouts (Gdouts Hermitage)

The Hermitage of Gdouts was located on the eponymous island in Lake Van. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the monastic compound consisted of only one church, Saint Garabed, in addition to monastic living quarters and the structure called the “outer house,” located on the mainland to the south of the island.

According to legend, the monastery was founded by Krikor the Illuminator. The first patriarch of the Armenian church was returning from Rome, bringing with him a piece of the True Cross and relics of seven saints. When he reached the island of Gdouts, he heard a voice that said – “Enshrine us here.” Krikor the Illuminator enshrined the seven relics in seven different locations, built a church at each site, each bearing the name of the corresponding saint, and appointed one of his disciples as prelate of the churches. Over time, the monastery’s order grew to 500 monks. One day, three of the monks fell ill and died. The servants, arriving in the dead monks’ room, saw that a gdouts (a group) of angels had gathered in the room, and called to each other – “A gdouts of angels has appeared! A gdouts of angels…” From that day on, the monastery came to be called the Gdouts Hermitage [1].

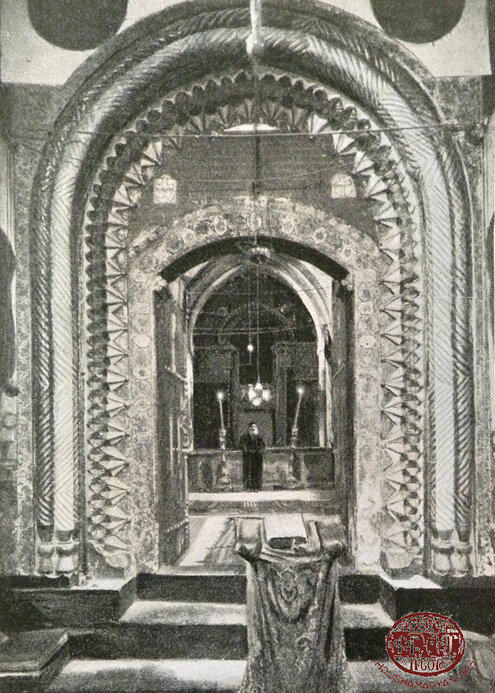

The Saint Garabed Church of the Gdouts Monastery and its narthex or “wall” were built of white, polished stones. The church was rectangular, and had two full columns and six half columns, above which rose horseshoe-shaped arches supporting an eight-cornered dome with a tapering spire. The columns were rectangular and simple. The altar arch was circular and horseshoe-shaped, adorned with a gilded crucifix. The main altar table was dedicated to the Holy Virgin, the right-side altar to Saint Garabed, and the left-side altar to Saint Sdepanos.

In the past, the church’s walls had been adorned with oil paintings. By the early 20th century, the only paintings that had survived were those of kings Apkar and Constantine the Great, both hanging from the columns.

The church’s doors, which opened onto the narthex, were crowned with several concentric arches, sculptures, and paintings. In the narthex, beside the entrance on both sides, were small tables covered by arches dedicated to Saint Minas and Saint Hagop, respectively.

A door in the northern wall of the narthex opened onto a small, vaulted chapel, housing a table dedicated to the holy archangels. This chapel also housed the monastery’s handwritten manuscripts.

On both sides of the western door of the narthex stood twin rectangular columns, which supported the columned belfry with its dome. Inside was a rock dedicated to Christ’s ascension.

The monks’ ancient living quarters were located to the southwest of the monastery. They consisted of principally one, or sometimes two rooms each, damp and with low ceilings, lining the two sides of a long hallway.

On the eastern side of the church was a large room, where the monastery’s eminent guests lodged. To the south of the church was the abbot’s quarters, consisting of two rooms.

The Gdouts Hermitage’s “outer house” was located on the mainland across Lake Van, to the east of the island. It consisted of a few rooms for monks; a small, ordinary church; a small school building; and a few buildings dedicated to trade (stables and granaries).

The “outer house” also included an orphanage, which in 1909 was home to about 15 orphans [2].

In the early 1910s, the Gdouts Hermitage owned large tracts of farmland, forests, orchards, a water mill, an olive oil press, 300 heads of sheep, 100 heads of cattle, and commercial properties in Van, Adrianapolis (Edirne), Tbilisi, and Istanbul [3]. The monastery’s total income was 300 Ottoman pounds, which was mostly used to fund the costs of the monastic order and the orphanage [4].

On the eve of the Genocide, the following eight villages in the Timar cluster of villages were under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Gdouts Hermitage – Alur, Khavents, Trlashen, Annavank, Amenashad, Marmed, Yegmal, and Chirashen [5].

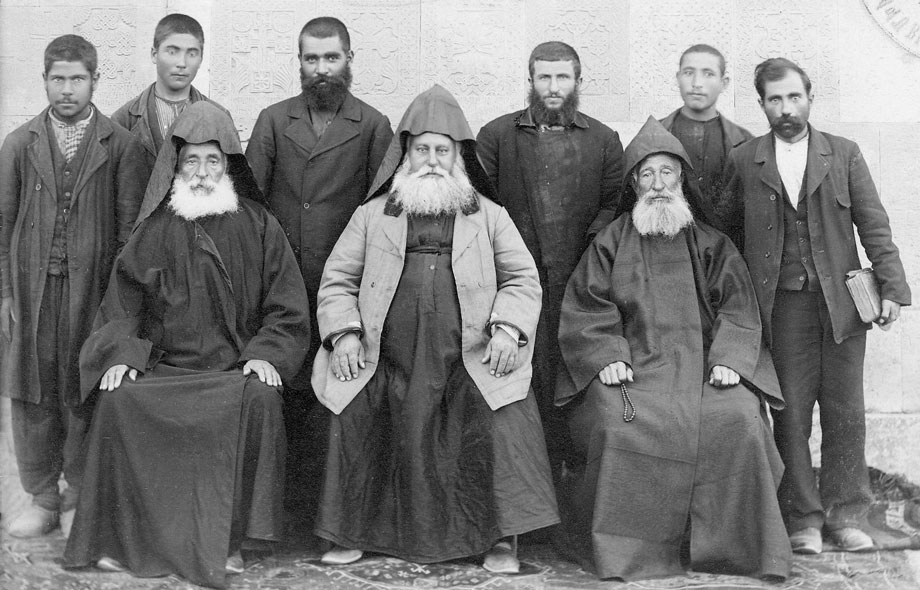

In 1873, the monastery’s order consisted of 12 priests, four senior deacons, two acolytes, five readers, and 11 mahdesis (laymen who had made pilgrimages to Jerusalem, and upon their return, had committed to living temporarily or permanently as members of the monastery’s order) [6]. A-To (Hovhannes Der-Mardirosian), who visited Gdouts in 1909, noted that the monastery’s order consisted only of three priests. The acting abbot, Father Sdepanos Aghazadian, lived in the “outer house” and kept the reins of the monastery’s finances firmly in his hands. The monastery’s avantabah (keeper of tradition) was the elderly Father Yeghia, who never left the hermitage. All affairs dealing with the outside world were entrusted to Father Krikor, who continually toured the monastery’s properties, supervised the planting and harvesting, and collecting the bdghin [7].

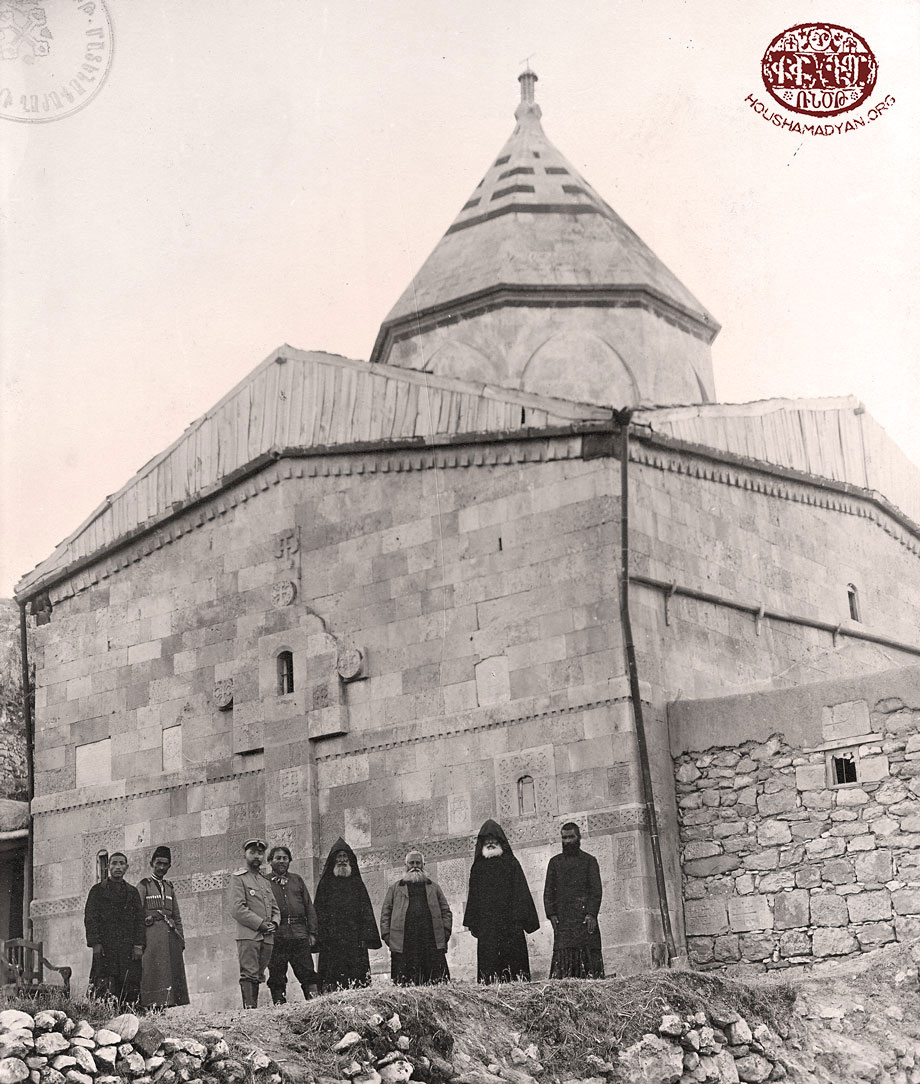

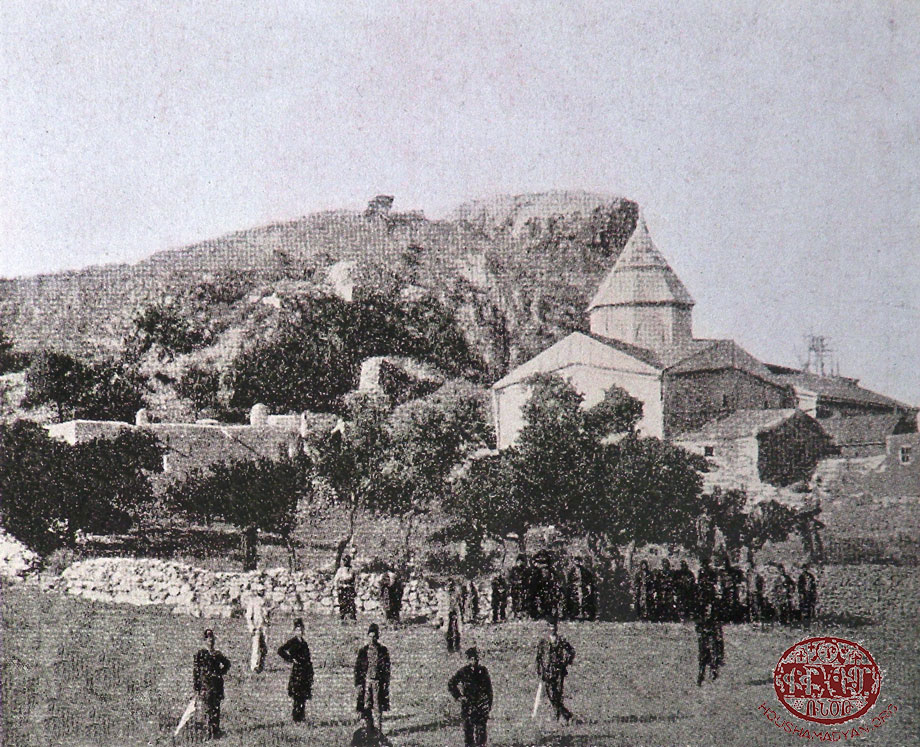

The monastic compound of the Gdouts Hermitage (Source: H.F.B. Lynch, Armenia. Travels and Studies, Vol. II, London, 1901).

A-to reported that the members of the monastery’s order cohabitated in harmony, and the monastery’s financed were marked with careful administration. The small library of the monastery was the object of particular care, with its carefully arranged collection of ancient, handwritten Bibles and other religious works [8].

In 1911, Senior Priest Father Yeghiazar Bedrosian was appointed acting abbot of the Gdouts Hermitage. He remained in that position until the Armenian Genocide, and was killed in 1915. On the eve of the Genocide, the other members of the monastic order were Father Boghos Vartabedian (killed in 1915), Father Sdepanos Der-Hovhannesian (killed in 1915), Father Sahag Adomian, Father Bedros Shahinian, Senior Priest Father Sdepan Aghazadian, and Deacon Nerses (killed in 1915) [9].

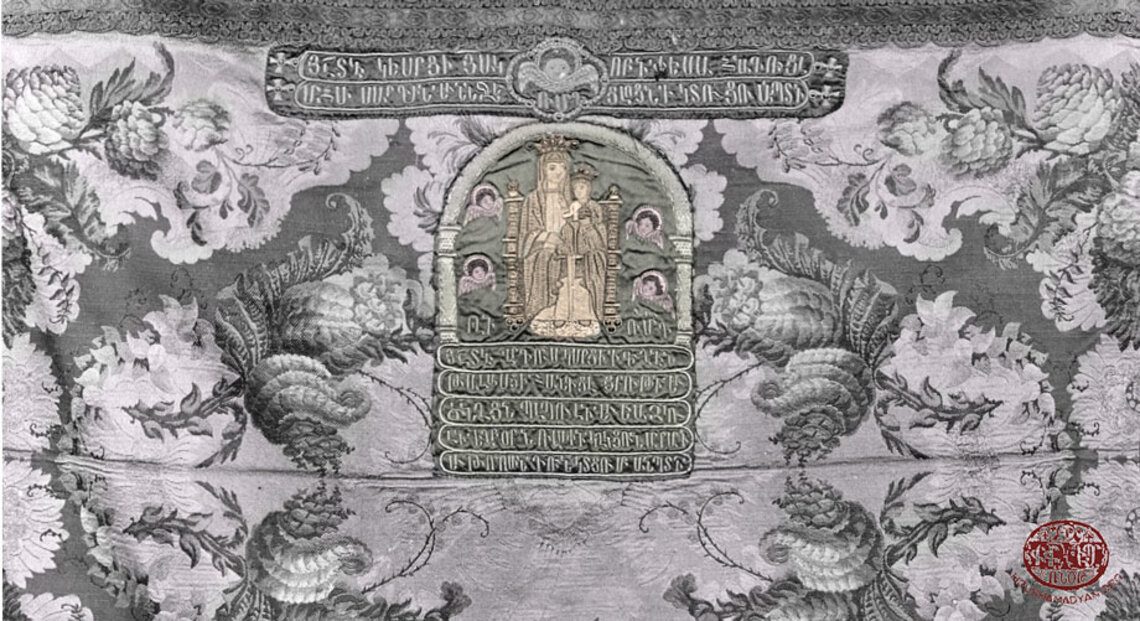

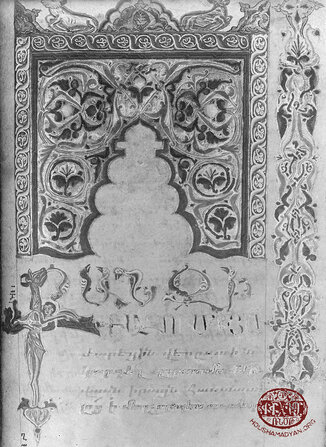

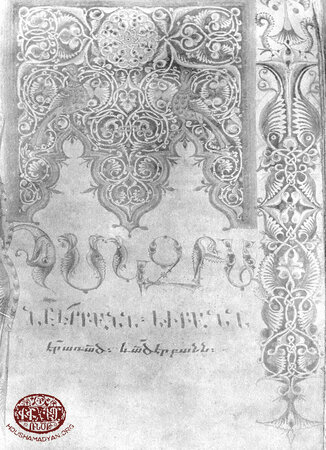

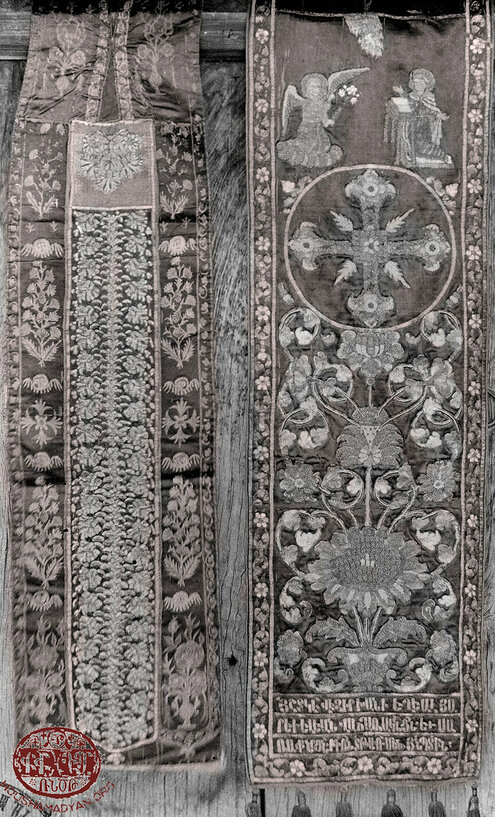

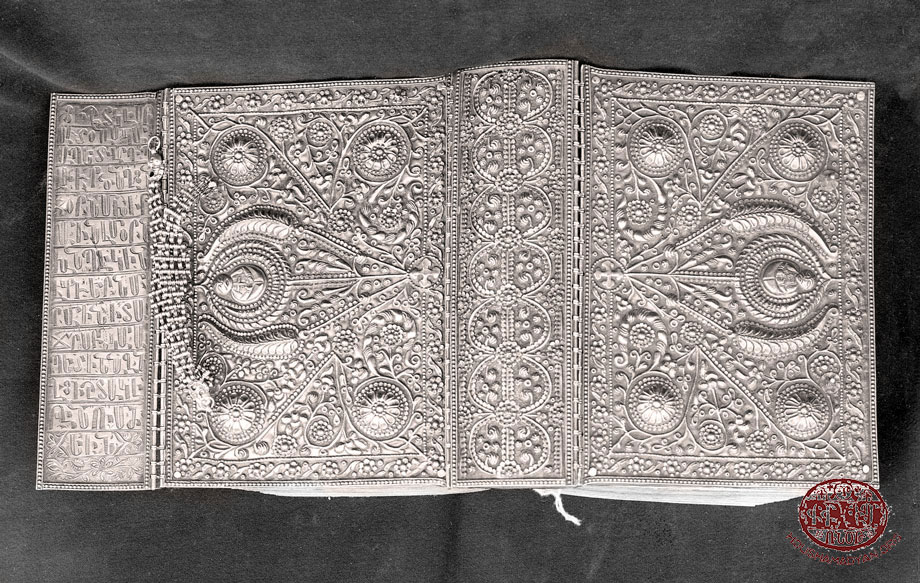

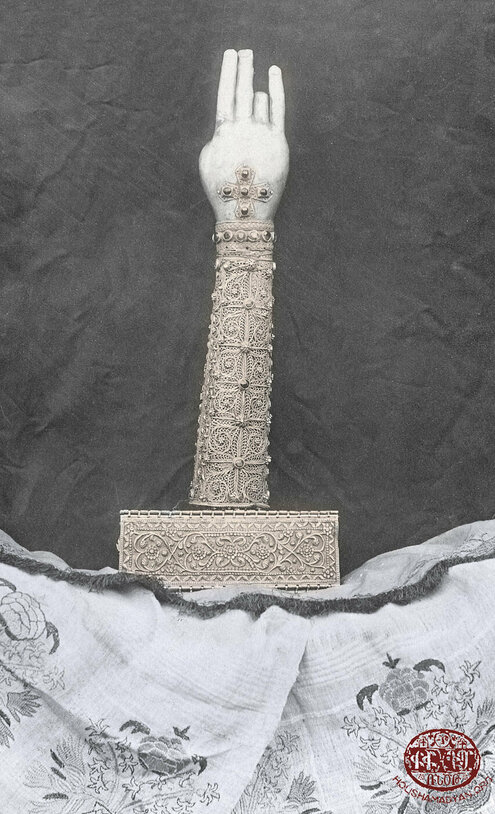

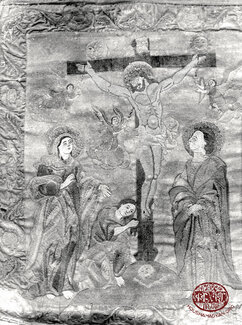

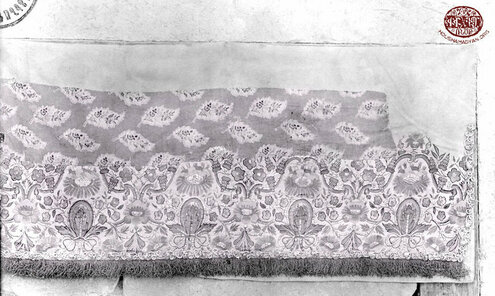

1), 2), 3) Different parts of the bishop’s attire kept at the Gdouts Hermitage and used during specific religious ceremonies (Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice).

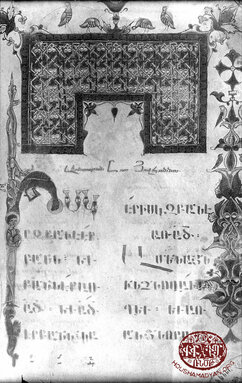

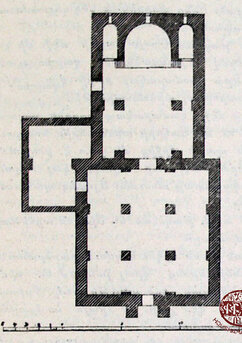

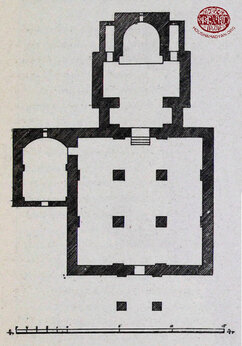

4) The layout plan of the monastic compound of Gdouts Island (Source: Y. Lalayan, Vasbouragan. Nshanavor Vanker [Vasbouragan. Renowned Monasteries], signature (section) A, Tbilisi, 1912).

The Lim Hermitage (Saint Kevork Monastery)

The Lim Hermitage was located on the island of Lim, located in the southeast of Lake Van. This is Lake Van’s largest and most expansive island [10]. The origin of the name “Lim,” according to our sources, is the Greek word “limne,” meaning lake, or “limin” (or “limen”), meaning port or safe harbor [11].

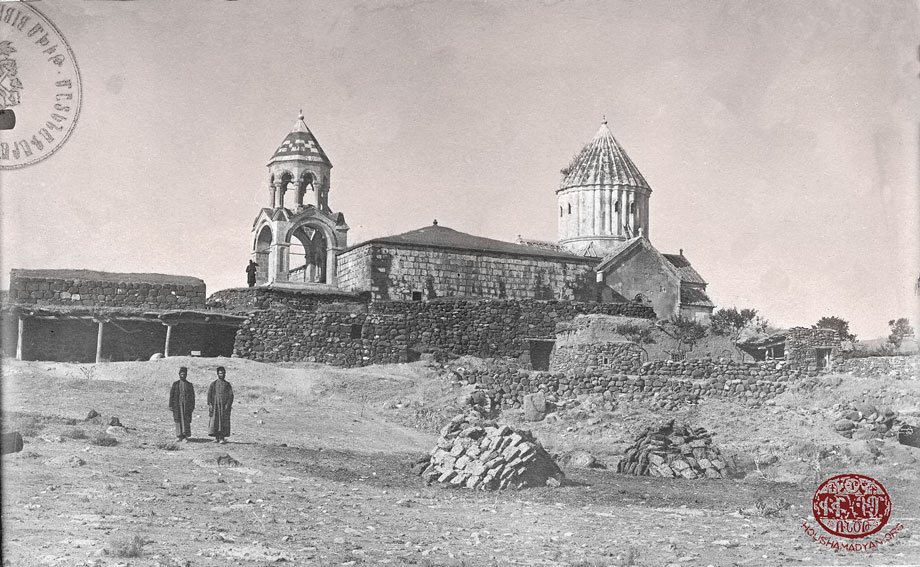

According to legend, as in the case of the Gdouts Hermitage, Lim was founded by Krikor the Illuminator [12]. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the monastic compound consisted of the Saint Kevork Cathedral, living quarters for the monks, and the compound’s “outer house,” located on the mainland to the south of the island [13].

The Saint Kevork Cathedral consisted of the church building itself, a narthex or “gate,” and a belfry. The church was called Saint Kevork because a relic of the saint was preserved near the church’s northern wall, alongside a small crucifix [14].

The church building was built of polished, white stones. The church’s walls were unadorned, and it had a low dome with a tapering spire. The drum consisted of circular and square half columns, with eight small windows carved into it. The church had four windows and one door, which opened onto the narthex. The narthex was rectangular, larger than the church building itself, and with a floor lowered by about a meter. Adjacent to the eastern wall of the narthex, on both sides of the door leading into the church, were two crucifixes dedicated to Saint Sdepanos and Saint Garabed. A depiction of the holy trinity hung above the door. Another such painting hung above the narthex’s western door, leading into the belfry. The narthex’s columns and walls were adorned by old and new oil-painted icons. On the northern side of the narthex was a door leading into a chapel called Saint Sion. On the west side of the narthex was the columned belfry, which contained a small liturgy table, dedicated to the holy archangels. A ceremony was held there once every year, on the Feast of the Ascension [15].

As in the case of the Gdouts Hermitage, Lim’s “outer house” consisted of living quarters for monks and an orphanage/school, home to 15 orphans, for which a new building and a new administrative building were built in 1883 [16].

In 1896, during the Hamidian massacres, the monastery’s “outer house” was attacked and plundered by Kurdish mobs. At the same time, at different times and during different waves of violence against Armenians, the monastery’s island served as a refuge for thousands of Armenians [17].

Bishop Eremia Devgants, who visited the monastery in the spring of 1873, reported that the monastic order had 32 members (14 priests, two senior deacons, two acolytes, eight readers, and seven mahdesi) [18]. In the early 1880s, Lim’s monastic order had almost 50 members [19], but by the late 19th century and early 20th century, that number had dropped. Already by the early 1910s, Lim’s order consisted of only eight members (seven priests and one archbishop) [20]. In 1911, the abbot was Father Hovhannes Husian, thanks to whom some of the monastery’s handwritten manuscripts and silverware were rescued in 1915 and sent to Echmiadzin (on the eve of the Genocide, the Lim Hermitage had a rich library consisting of 550 handwritten manuscripts and more than 3,000 printed books) [21].

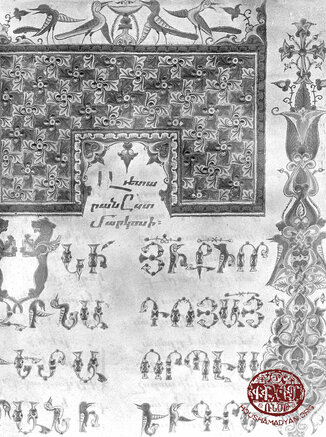

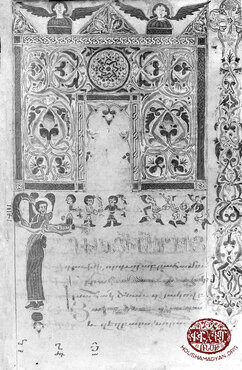

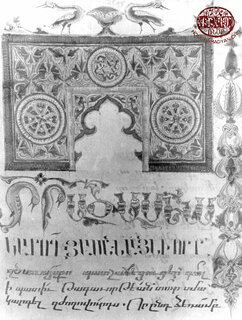

1) A lectern used in the Lim Hermitage (Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice).

2), 3) Lim Hermitage. Examples of the handwritten manuscripts preserved in the monastery’s library/repository (Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice).

4) The layout plan of the monastic compound of Lim Island (Source: Y. Lalayan, Vasbouragan. Nshanavor Vanker [Vasbouragan. Renowned Monasteries], signature (section) A, Tbilisi, 1912).

The monastery’s monks were renowned for their austere lifestyle. The monks’ cells were dark and damp rooms lining the two sides of a dark hallway. Each monk only had one room, where he slept and spent his free time before and after services. Monks were not provided with beds. They slept and sat on the ground, and consequently almost all them suffered from arthritis.

The monks’ diet was exceedingly sparse. Meat and wine were generally forbidden. The diet usually consisted of vegetables, with the addition of milk, yogurt, and tanabour on holidays. All fast days were observed strictly. The monks fasted on Mondays, in addition to Wednesdays and Fridays. They usually ate one meal per day, in the refectory. During these meals, one of the monks read out passages from the Bible. Almost all meals consisted of a single dish [22].

In the late 19th century, according to ancient monastic tradition, seven services were held in the monastery every day. In the early 1900s, this regimen was relaxed, and the number of daily services was reduced to five [23].

The Lim Hermitage’s spiritual jurisdiction extended over 16 villages of Timar, including Chanig, Tarapeg, Norshen, Ader, Noravants, Koms, Shahkealti, Kharashig, Amoug, and Pirgarip; as well as the Holy Virgin (Khatoun Diramayr) Monastery of Timar and the Saint Sahag Monastery of Echmiadzin [24].

The monastery owned large tracts of farmland, fields, forests, and orchards, as well as four water mills and commercial properties in Van and elsewhere [25]. The income derived from the monastery’s assets was used to fund the needs of the monastic order and the monastery school.

The Holy Virgin Monastery of Alyur

The Holy Virgin Monastery was located about ten minutes south of the Armenian-populated village of Alyur in Timar. The date of the monastery’s founding has been lost to history, but it is presumed that it was built no later than the 13th century, because the outer façade of the its northern wall includes a khachkar that was carved in 1214 [26].

E. Devgants, who visited the monastery in April of 1873, noted that the monastic compound consisted of the church building, built of polished stones; the narthex; and several structures devoted to administration and the monastery’s economy (prelacy, school, administrative building, storeroom, cowshed, and hay barn). The monastery’s abbot was Father Garabed. In the winters, he also served as the teacher in the monastery’s school, which the village boys attended. In the summers, he worked in the monastery’s fields [27]. Manvel Mirakhorian, who visited the monastery in 1883, also mentioned the abbot, but without naming him [28].

According to records from the early 1900s, the monastery no longer had an active, permanent abbot. Instead, it was placed under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Gdouts Hermitage, and was administered by a series of clergymen visiting from there [29]. Records also indicate that by this time, although the monastery still possessed certain properties and agricultural assets, due to the lack of effective administration of the its finances, the residents of the village of Alur were using the its fields and lands for their own benefit [30].

The Saint Echmiadzin Monastery

The Saint Echmiadzin Monastery was located on the eastern coast of Lake Van, on the road connecting the “outer houses” of the Gdouts and Lim hermitages. The monastic compound consisted of two churches, the Saint Echmiadzin and the Holy Virgin, and one chapel [31] (according to another source, the compound consisted of one chapel (Upper Echmiadzin) and a church (Inner Echmiadzin) [32]). A contemporary chronicler, K. Sherents, described Saint Echmiadzin as a “small monastery” without going into the details of the different structures [33].

According to legend, the area of the monastery had once been a sanctuary for ascetics, to whom Jesus Christ had once appeared. As Christ is also called Miadzin (only-begotten), the monastery was called Saint Echmiadzin [34] (“Echmiadzin” translates into “the descent of the only-begotten”).

Y. Devgants, who visited the monastery in 1873, reported that at the time, it served as a farm for the Lim Hermitage, and had an abbot and one monk [35].

At the start of the 20th century, the monastery had already lost its permanent order of monks. Records only mention a serving abbot [36]. It was under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Lim Hermitage, and members of the Lim order regularly visited to manage its finances and oversee its assets (which included a large mulberry orchard of 2,000-3,000 mulberry trees, gardens, forests, fields, farmland, pastures, etc.) [37].

The monastery’s pilgrimage day was the Feast of Ascension. On that day, it hosted large crowds from the neighboring villages [38].

Ererna Saint Sahag (Saint Sahag of Ererin)

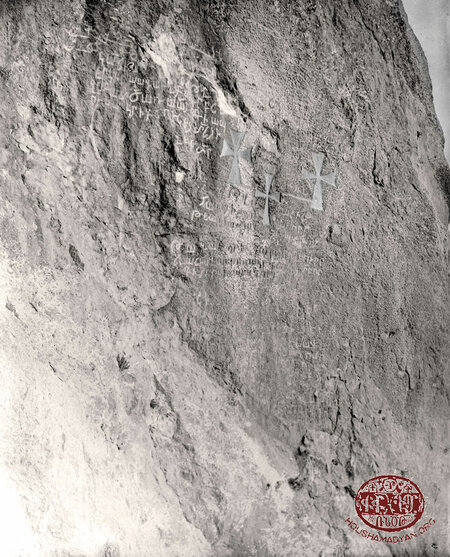

The Ererna Saint Sahag Monastery was located on the flank of a mountain rising above the Armenian-populated village of Ererin in Timar. The monastery compound was walled, and consisted of a domed church and a narthex. Prior to the Genocide, the monastery was abandoned, and its buildings lay in a dilapidated state.

The monastery housed a relic, the right hand of Saint Sahag Bartev (Saint Isaac of Armenia). In the 1840s, when the monastery was abandoned [39], the relic was transported to the Lim Hermitage, which held spiritual authority over Ererna Saint Sahag. Saint Sahag was one of the more celebrated saints among the people of Timar. The locals believed that his powers were particularly effective in healing illnesses of the eyes [40].

Vartavar Sunday was dedicated to celebrations of Saint Sahag. Pilgrims from various parts of Timar gathered at the monastery, most of them young. The Divine Liturgy was celebrated [41].

The summit of the mountain on which the monastery was located was called Khachkloukh (Head of the Cross). There, according to legend, Saint Krikor the Illuminator had lived as an ascetic and had consecrated a cross. A small chapel had been built on the summit, and was also a renowned pilgrimage site [42].

At a distance of half an hour to the east of the Saint Sahag Monastery were the ruins of the main wall of another monastery, which was purported to be the Saint Bedo Monastery. A “holy” spring flowed near this site [43].

Y. Devgants, who visited Saint Sahag in 1873, noted that the establishment had no serving monks or priests, and that the compound was maintained by the Kherabed clan of Ererin, who lived in the monastery and worked the fields, although ignoring the upkeep of the monastery’s buildings [44].

In the 1910s, the monks of the Lim Hermitage planned to establish a summer school at the Saint Sahag Monastery, for the hermitage’s orphans. But the lack of resources and the outbreak of the Armenian Genocide derailed these plans.

The monastery owned farmland, which was let out to the residents of surrounding villages [45].

The Churches of Timar

Below we present a list of churches of the villages of Timar on the eve of the Armenian Genocide, according to various sources. The towns and villages included are only those that had a functioning church according to documented evidence.

Averag/Alabayır

187 households, 1,061 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the village had three serving priests [46].

Atikeozal/Adıgüzel

31 households, 226 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [47].

Alyur/Alaköy

343 households, 1,955 Armenians.

The Saint Krikor, Saint Sdepanos (built in 1911), and Saint Naregatsi churches. In the mid-1850s, the village had three serving priests. On the eve of the Genocide, the village’s four serving priests were Father Garabed Touigian (killed in 1915), Father Hovhannes Der-Hovhannesian (killed in 1915), Father Sarkis Der-Sarkisian, and Father Sdepanos Proudian [48].

Aghchaveran/Akçaören

32 households, 147 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church [49]. In the mid-1850s, the village did not have a functioning church or a serving priest [50].

Amenashad/Arısu

40 households, 204 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (formerly a monastery). On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priest of the village was Father Simon Yeghiazarian [51].

Amgoupert (Amuk, Norkegh)/Yeşilsu

30 households, 210 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church [52].

Annavank/Dibekdüzü

50 Armenians, 254 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood). On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priest was Father Hovagim Khachadourian [53].

Asdvadzadzin (Diramayr)/Ermişler

63 households, 462 Armenian.

The Holy Virgin Church (Khatoun Diramayr). It had formerly operated as a monastery. The building was described as beautiful, crowned with a white and magnificent dome. According to legend, the monastery occupied a site that previously housed a pagan temple, where three brothers had served as priests (Shirag, Zirag, and Mirag). The three brothers had accepted the Christian faith after hearing the sermons of Saint Thaddeus the Apostle or Saint Nerses Bartev [54].

Manvel Mirakhorian, who visited the village in 1883, stated that the village had two priests. A grade school functioned adjacent to the monastery, serving 35-40 pupils [55].

The pilgrimage day of the church was the Holiday of the Assumption of Mary. On that day, large crowds gathered on the island (8,000-10,000 people), coming from nearby towns and villages, as well as from Persia and Russia. Among the pilgrims were many Kurds, Turks, and Assyrians [56].

Ader/Yaylıyaka

71 households, 444 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (roof built of wood) (or the Holy Virgin Church, according to another source [57]). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [58].

Adnagants/Yeniköşk

31 households, 247 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar) [59].

Paytag/Özkaynak

28 households, 195 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood) [60].

Keolou/Göllü

15 households, 91 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church [61]. In the mid-1850s, the village had no functioning church [62].

Koms/Emek

53 households, 340 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (roof built of wood) [63]. The serving clergyman was Father Margos [64].

Gyusnents/Kasımoğlu

138 households, 825 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the village had two serving priests [65].

Tarapeg/Derebey

37 Armenians, 243 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [66].

Yegmal

31 households, 226 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (according to another source, the Saint Kevork Church (roof built of wood) [67]). On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priest was Father Krikor Hagopian [68].

Ererin/Dağönü

151 households, 938 Armenians.

The Saint Hovhannes and Saind Sdepanos churches. In the mid-1850s, the village had three serving priests [69].

Khavents (Havents)/Ağartı

106 households, 633 Armenians.

The Saint Giragos Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had two serving priests [70]. On the eve of the Genocide, the village’s serving priests were Father Apraham Der-Hovhannisian and Father Garabed Der-Kevorkian [71].

Khjishg/Halkalı

132 households, 775 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the village had six serving priests. A Bible called Sheg was kept in the church [73].

Dzagdar/Tevekli

38 households, 231 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [74].

Godj

26 households, 137 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church [75]. In the mid-1850s, the village had no functioning church [76].

Marmed/Topaktaş

153 households, 811 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had two serving priests [77]. On the eve of the Genocide, the village’s serving priests were Father Hagop Der-Hagopian, Father Mardiros Der-Garabedian, and Father Nerses Tavitian [78].

Norshen/Kumluca

45 households, 270 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [79].

Norovants/Esenpınar

37 households, 215 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [80].

Shahkealti (Shenig)

22 households, 156 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos (Saint Steven) Church (built of stone and mortar) [81].

Boghants/Aşıt

71 households, 451 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (roof built of wood) [82].

Chanig/Gedikbulak

100 households, 714 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (roof built of wood) [83]. The serving priest was Father Hovhannes [84].

Chikrashen/Otluca

76 households, 475 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (built of stone and mortar) [85]. On the eve of the genocide, the village had two serving priests, Father Hagop Giragosian and Father Sahag Markarian [86].

Sosrat (Dzordzorpert)/Tabanlı

42 households, 251 Armenians.

The Holy Cross Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [87].

Drlashen

95 households, 657 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had three serving priests [88]. On the eve of the Genocide, the village’s serving priest was Father Simon Khachadourian [89].

Pirgarip

57 households, 373 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the village had one serving priest [90].

Keochani/Güveçli

111 households, 705 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood) [91]. On the eve of the Genocide, the church’s serving priests were Father Hovhannes and Father Kevork [92].

Keoprikeoy

3 households, 12 Armenians.

The village had no functioning church. The residents relied on Father Simon of Drlashen for their spiritual needs [94].

[1] Y. Lalayan, “Vasbouragan. Nshanavor Vanker” [Vasbouragan. Renowned Monasteries], Azkakgragan Hantes [Ethnographic Review], Tbilisi, Book XXII, 1912, page 88.

[2] A-To, Vani, Bitlisi, yev Erzurumi Vilayetnere [The Provinces of Van, Bitlis, and Erzurum], Yerevan, Cultura Press, 1912, page 29.

[3] Yervant Lalayan, who visited Van in the summer of 1910, assembled a detailed list of Gdouts Hermitage’s properties (Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, page 93).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Y. Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun Partsr Hayk yev Vasbouragan 1872-1873 [Travels in Upper Hayk

and Vasbouragan 1872-1873], Yerevan, History Institute of the Academy of Science of Armenia, 1991, pages 205-251.

[7] A sort of tax paid by the villagers to the monasteries, in the form of grain.

[8] A-To, Vani, Bitlisi, yev Erzurumi Vilayetnere, page 29. During the Armenian Genocide (1915-1916), 202 handwritten manuscripts were transported from the Gdouts Hermitage to Echmiadzin, and are currently housed at the Madenataran (L. Toumanian, “Lim yev Gdouts Menasdannere Medz Yegherni Orerin” [“The Lim and Gdouts Hermitages during the Armenian Genocide”], Echmiadzin, Official Monthly of the Catholicosate of the Holy See of Cilicia, 2013, D (69), page 106).

[9] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [Calvary of Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915], New York, 1985, page 52.

[10] K. Sherents, Srpavayrer. Deghakroutyun Vasbouragani-Vana Nahanki Klkhavor Yegeghetsyats, Vanoreyits yev Ousoumnaranats [Holy Sites. Geography of the Most Significant Churches, Monasteries, and Educational Institutions of Van-Vasbouragan], Tbilisi, 1902, page 76.

[11] H. Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere [The Monasteries of Van-Vasbouragan], Part A, Vienna, Mkhitarine Press, 19140, page 4.

[12] R. Atayan, “Lim Anabad” [“Lim Hermitage”], Krisdonya Hayasdan Hanrakidaran [Encyclopedia of Christian Armenia], Yerevan, 2002, page 412.

[13] Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, page 85.

[14] Ibid., page 90.

[15] Ibid., page 91.

[16] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part A, page 45.

[17] Father Magar Der-Hovhannisian, “Vana Dzovn yev ir Gghzinere” [“The Sea of Van and its Islands”], Puzantion, February 23 (March 8), 1913, N. 4368.

[18] Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun, page 260.

[19] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part A, page 44.

[20] Puzantion, Constantinople, February 23 (March 8), 1913, N. 4368.

[21] Toumanian, “Lim yev Gdouts Menasdannere…”, page 104; K. Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan Ngarakire Medz Yegherni Nakhorein. Mas Arachin: Vani Vilayeti Gendronagan, Husisayin yev Arevelyan Kavarnere” [The Historical and Ethnographic Character of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide, Part One: The Central, Northern, and Eastern Districts of Van Province], Vem All-Armenian Review, Year Seven (13), N. 2 (50), April-June, 2015, page 125.

[22] Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, page 88.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part A, page 46.

[25] For a list of monastery properties, see Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, pages 91-92.

[26] Ibid., page 99; also see Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part A, page 343.

[27] Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun…, page 266.

[28] M. Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Kavars Arevelyan Dadjgasdani. Deghagroutyunk Saren yev Tsoren, Hnen yev Noren Bidani Kidnots [Descriptive Chronicle of Travels to Armenian-populated Provinces of the Eastern Ottoman Empire. Reports and Practical Information on Mountains and Valleys, on the Old and the New], Part B., Constantinople, M.G. Sareyan Press, 1885, page 280.

[29] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 74.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Lalayan, Azkakgragan Hantes, page 99.

[32] Puzantion, Constantinople, February 23 (March 8), 1913, N. 4368.

[33] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 75.

[34] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part A, page 350.

[35] Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun…, pages 254-255.

[36] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 75.

[37] Puzantion, Constantinople, February 23 (March 8), 1913, N. 4368.

[38] Lalayan, Azkakgragan Hantes, Book XXI, 1911, page 99.

[39] Father Magar Der-Hovhannesian, who was member of the monastery’s order, wrote in 1911 that it had been 70 years since the monastery had been left to the care of others as if it were a useless possession (Puzantion, Constantinople, February 23 (March 8), 1913, N. 4368).

[40] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 76.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, Book XXI, 1911, page 99.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun…, pages 256.

[45] Puzantion, Constantinople, February 23 (March 8), 1913, N. 4368.

[46] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180; Hayots Tseghasbanoutyune Osmanian Tourkiayoum: Verabradznerou Vgayoutyunner: Pasdatghteri Joghovadzou [The Genocide of Armenians in Ottoman Turkey: Testimonies of Survivors: Anthology of Documents], Volume I, Van Province, page 36.

[47] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[48] Ibid.; Teotig, Koghkota…, page 53; Hayots Tseghasbanoutyune Osmanian Tourkiayoum…, page 117.

[49] Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan…”, page 122.

[50] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[51] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 54.

[52] Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan…”, page 124.

[53] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 54.

[54] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part A, pages 352-353.

[55] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, Part B., pages 271-272.

[56] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 80; Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, Part B., pages 274-275.

[57] Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan…”, page 122.

[58] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180; T.Kh. Hagopian, S.D. Melik-Pakhsian, H.Kh. Parseghian, Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri Deghanounneri Pararan [Dictionary of Place Names of Armenia and Surrounding Areas], Volume 1, A-D, Yerevan, Yerevan State University Press, 1986, page 370.

[59] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180; Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, Volume 1, page 372.

[60] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[61] Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan…”, page 123.

[62] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[63] Ibid.; Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, Volume 1, page 370.

[64] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 45.

[65] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[68] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 54.

[69] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180; Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, Volume 2, D-G, Yerevan, Yerevan University Press, 1988, page 364.

[70] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[71] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 54.

[72] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180; Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, Volume 2, page 729.

[73] Hayots Tseghasbanoutyune Osmanyan Tourkiayoum…, page 133.

[74] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180; Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, Volume 2, page 830.

[75] Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan…”, page 124.

[76] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[76] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 53.

[79] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 45.

[85] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[86] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 54.

[87] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[88] Ibid.

[89] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 53.

[90] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[91] Ibid., Hayots Tseghasbanoutyune Osmanyan Tourkiayoum…, page 146.

[92] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 45.

[93] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1878, September, page 180.

[94] Teotig, Koghkota…, page 54.