The Churches and Monasteries of Hayots Tsor

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 03/12/18 (Last modified 03/12/18) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Monasteries of Hayots Tsor (nahiye)

According to the figures of A. Menag, a reporter for the Askhadank weekly newspaper published in Van, there were 12 monasteries in the area of Hayots Tsor in 1911, of which five were standing, and seven were in ruins. The monasteries that were still standing were the Holy Virgin of Ankgh, the Holy Cross or Saint Marinos of Srkhou, the Saint Kevork of Khek, the Saint Abraham Monastery, and the Holy Virgin or Dzidzaghaper. The monasteries that were in ruins or semi-dilapidated were the Saint Vartan (which was submerged under the waters of Lake Van), the Vart Badrig Chapel, the Khntragadar Monastery, the Chapel of Adom, the Saint Vartan of Aregh, the Holy Virgin of Khosb, and the twin monasteries of Saint Sarkis and Saint Kevork (submerged under the waters of Lake Van) [1].

The Holy Virgin Monastery of Ankgh (Kapenits Saint Kevork)

The Holy Virgin Monastery of Ankgh was located 1.5 kilometers southeast of the village of Ankgh. It consisted of one small, unimpressive church, housed in an old, ordinary building. The main altar was dedicated to the Holy Virgin, and the altars to the right and left of the main altar were dedicated to Saint Kevork and Saint Sdepanos, respectively [2]. According to another source, Saint Kevork was a separate church [3]. There was also a smaller altar near Saint Kevork, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, with a “yughadzoran” window. From this window dripped an oily liquid, which the locals had dubbed “the tears of the Holy Virgin” and to which they ascribed miraculous healing powers [4].

According to legend, the Holy Virgin was founded by Thaddeus the Apostle, who had also stored the Holy Lance, as well as the Holy Virgin’s veil and a bottle of oil used by her, inside the monastery [5].

In 1882, the United Society opened a school at the Holy Virgin. The school operated until 1896, and was plundered and burned, alongside the rest of the compound, during the Hamidian massacres [6].

The monastery is mentioned in records as the largest and preeminent pilgrimage site in Hayots Tsor. Its pilgrimage day was the Feast of the Assumption of Mary. On that day, the site would host large crowds consisting not only of Armenians, but also of Kurds and Turks [7].

The monastery was considered to be functioning but had no serving monks. Y. Devgants, who visited it in the summer of 1873, found it in a relatively prosperous state. It had a serving abbot, Father Kevork, as well as three ploughmen, a cowherd, and a shepherd. The caretaker was the abbot’s mother [8]. The monastery continued to be administered by Father Kevork’s family in subsequent years [9].

But already by 1911, records indicate that the church was in a dilapidated and unimpressive state, and the monastery compound uninhabited. The records note that that monastery’s estates (large tracts of land, tree orchards, pastures, water mills and other structures) had previously been appropriated by a single priest and his family (presumably a refence to the Der Kevorkian family), who had paid a paltry sum (moukata) to the Aghtamar Catholicosate. The Catholicosate had, in recent years, taken to the practice of renting out the monastery’s lands in exchange for 40 units of wheat (around 17 Ottoman pounds) per year [10].

The Holy Virgin Monastery of Eremer (Dzidzaghaper Holy Virgin)

The Dzidzaghaper Holy Virgin Monastery was located approximately half a kilometer east of the Armenian-populated village of Eremer, at the tip of a cluster of hills that rose in a cyme-like pattern from the valley [11].

The Holy Virgin, among other monasteries, was under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Aghtamar Catholicosate. It was renowned for the beautiful views it offered, its orchards, and the fertile soil of its fields [12].

According to legend, the monastery was built by Thaddeus the Apostle at the very site where the smiling Holy Virgin had appeared to him. This was the origin of the monastery’s moniker of “dzidzaghaper” [“that which brings a smile”] [13].

The monastery consisted of one church, an adjacent narthex, and the wall surrounding the compound [14]. The structures were built of ordinary, unpolished stones. The church had a height of eight meters and a width of six meters. It had no columns, and was an ordinary, domed building. The narthex was built in the same shape, and also lacked columns [15].

On the eve of the Genocide, the monastery did not have an active order. The priests of Eremer served as its abbots. In late 1895, the monastery was plundered by Kurdish bandits. The abbot, Father Mardiros, escaped to Van, but then fell victim to the massacres that struck the city in June 1896 [16].

The Armenians of Eremer had great reverence for the Holy Virgin. K. Sherents writes that all of them, women and men, would visit the monastery as soon as it opened its doors in the morning, would kneel before it and its kiss its stones and cross, and only then head to their village church for service [17].

According to figures from 1903, the monastery housed the Eremer village school, with its one teacher and 40 pupils [18].

According to an account from 1911, a priest and his family lived on the premises of the monastery, and supervised its extensive properties (fields, orchards, etc.) The priest’s salary was paid by the Aghtamar Catholicosate, and consisted only of 25 units of wheat per year, equivalent to 10 Ottoman pounds [19].

The Saint Nshan or Saint Marinos Monastery of Srkhou

The monastery was located in the south of Hayots Tsor, at a distance of approximately two kilometers (30 minutes’ walk) from the Kurdish-populated village of Galbalasan. It stood beside a boulder, in a rocky valley. The year of its founding is unknown, but judging from a khachkar located on the premises, it must have been built by the 13th century at the latest [20]. According to records, the monastery had previously served as a large convent, and was home to 300 nuns under the leadership of Saint Marianos, after whom the site was later named [21]. The locals pointed to an unimpressive and dilapidated chapel nearby as the final resting place of Saint Marianos. This chapel was a pilgrimage destination for infertile women, as well as women who were unable to lactate [22].

The monastery consisted of a church with a central dome and related structures, all built in a row behind a wall that rose on the western side of the compound [23].

M. Mirakhorian, who visited the monastery in 1883, mentioned that the compound was still partially standing. Two year prior to his visit (in 1881), it had still had an abbot, who later abandoned the monastery. The Aghtamar Catholicosate, which had spiritual jurisdiction over Saint Nshan, had let out its approximately 400 plots of farmland to the local villagers [24].

The monastery was plundered during the 1896 Hamidian massacres [25].

According to an account from 1911, the monastery was abandoned and uninhabited, although only “years earlier” it had had proper facilities and many monks. The monastery’s farmlands, about 300 plots, were still being let out to local villagers in exchange for 35 units of wheat (15 Ottoman pounds) per year [26].

The Saint Kevork Monastery of Khek

The monastery was located to the southwest of the Armenian-populated Khek (Hayg) village of Hayots Tsor, at a distance of about 20 minutes’ walk from it.

The date of Saint Kevork’s founding is unknown. M. Mirakhorian, who visited it in 1883, described it as an old monastery that lacked a cathedral. He also mentioned the abbot, Sdepan Der-Sarksian, thanks to whose efforts a few new rooms had been built in the monastic compound. The monastery also had a functioning school [27].

Saint Kevork shared the fate of other monasteries in Hayots Tsor, and was plundered and burned in 1895 [28]. It was apparently abandoned after this catastrophe.

An account from 1911 describes Saint Kevork as “a monastery built in the old and tasteless fashion.” It was reported that the compound’s structures had once been quite luxurious, but had fallen into disrepair and dilapidation due to years of neglect [29].

The monastery owned large tracts of arable lands, which the Aghtamar Catholicosate had let out in exchange for 40 units of wheat (approximately 17 Ottoman pounds) per year [30].

The Saint Abraham Monastery of Khek

The monastery was located approximately two kilometers southeast of the Khek village of Hayots Tsor – a distance of about an hour from the Saint Kevork Monastery. It stood at the feet of a mountain rising above a valley [31]. The monastery was dedicated to Abraham, a student of Saint Ghevont’s, who is mentioned by Armenian historian Yeghishe. The locals believed that the spring that flowed near the compound, and which had appeared in response to Abraham’s prayers, had miraculous healing properties [32].

In 1873, the monastery still had an abbot, by the name of Father Bedros, who also served as the abbot of the Saint Kevork Monastery of Khek [33].

M. Mirakhorian, who visited the monastery in 1883, described the compound’s cathedral as a robust, beautiful structure. He also stated that the monastery had been abandoned, and the monks’ quarters were semi-dilapidated [34].

The monastery owned land, which was let out to locals.

Saint Abraham’s pilgrimage day was on the Feast of the Ascension. On that day, large crowds of pilgrims converged on the monastery from Armenian villages all over Hayots Tsor, as well as from elsewhere. The monastery’s abbot would celebrate the Divine Liturgy in the presence of these pilgrims [35].

The Churches of Hayots Tsor (nahiye)

Below, we present a list of the churches in the villages of Hayots Tsor on the eve of the Armenian Genocide. The villages are listed in alphabetical order (Armenian alphabet). We have only included villages in which the presence of a church could be confirmed.

Ankgh/Deonemech (Dönemeç)

108 households, 678 Armenians.

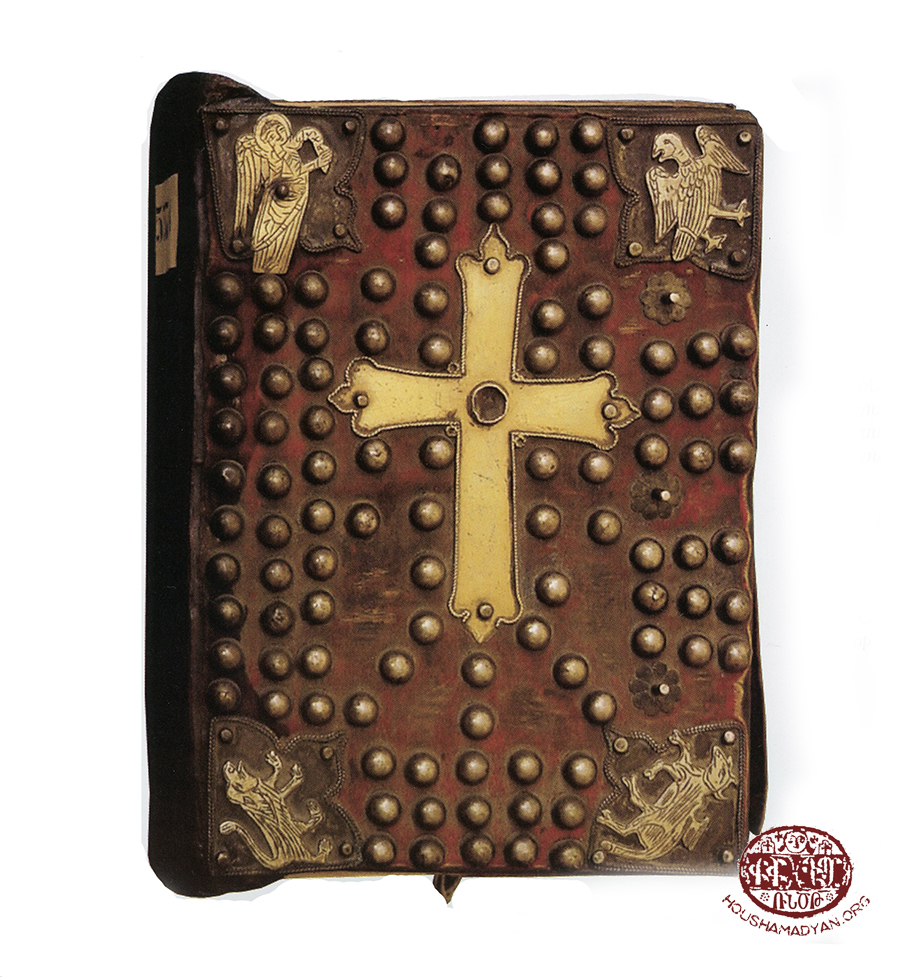

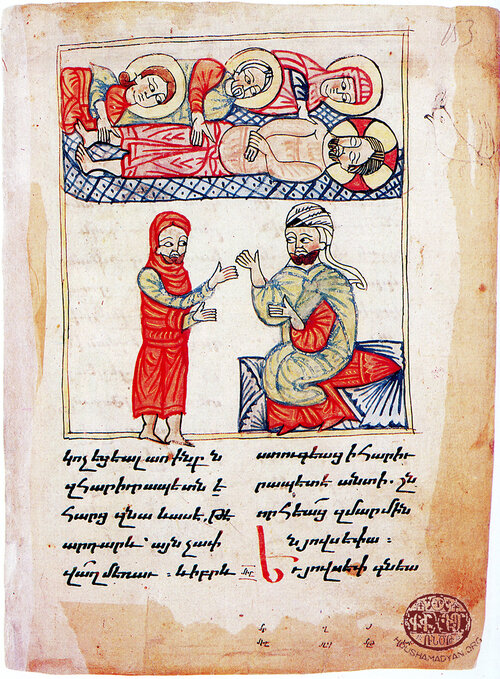

The Saint Kevork Church (functioning), and the Saint Sarkis and Saint Dziranavor churches (in ruins). In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest. Prior to the Armenian Genocide, a handwritten manuscript of the Bible was preserved at the Saint Kevork Church [36].

Angshdants/Parmakkape (Parmakkapı)

67 households, 411 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar) [37].

Aregh/Bozyighit (Bozyiğit)

26 households, 175 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church [38].

The Saint Vartan Monastery stood approximately two kilometers east of the village. According to legend, Vartan Mamigonian’s head was preserved at this monastery, and for that reason it was called Saint Vartan [39].

M. Mirakhorian, who visited the monastery in 1883, described it as deserted. Out of the entire monastic compound, only a small church still stood. Mirakhorian also noted that once every year, on the Holiday of Saint Vartan, the village priest of Aregh would celebrate the Divine Liturgy at this church, in the presence of large crowds of pilgrims [40].

According to an account from 1911, the villagers had taken over the farmlands belonging to the monastery, without paying any rent to Varakavank, which had spiritual jurisdiction over Saint Vartan [41].

Asdvadzashen/Chavoushtepe (Çavuştepe)

48 households, 351 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest [42]. The fort of Haygapert (Urartian Sartourikhinili) was located east of the village [43].

Aradents/Kasr

40 households, 235 Armenians.

The Saint Krikor the Illuminator Church (built of stone and mortar) [44].

Eremer

82 households, 432 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (built of stone and mortar) [45].

Ishkhanikom/Bakemle (Bakımlı)

70 households, 409 Armenians.

The village had two functioning churches, one of which was Saint Hovhanness (built of stone). The other church’s name is unknown. In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest. In the vicinity of the village were the ruins of the Kava Holy Virgin and “Arakelots Tar” monasteries, as well as the ruins of the Saint Sarkis and Saint Haroutyun churches [46].

Kharagants/Enginsu

36 households, 219 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood). In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest [47]. The Saint Kevork and Saint Sarkis monasteries were located in the vicinity of the village, but were submerged under the waters of Lake Van [48].

Khek (Hayk)

34 households, 219 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church [49].

Khosb/Sakalar

52 households, 291 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church [50]. A survey conducted in 1858 also mentioned the Holy Virgin Church (built of stone and mortar) and the Saint Hagop Church (roof built of wood) [51]. The Holy Virgin Monastery was located approximately 1.8 kilometers west of the village. M. Mirakhorian, who visited the monastery in 1883, described it as “quite trim and beautiful… Though the building was undamaged, it stood shuttered and abandoned amid the old and new khachkars, and against the backdrop of a beautiful scenery” [52].

Khorkom/Dilkaya

65 households, 435 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (roof built of wood) [53]. In the mid-1850s, the community had two serving priests. Within the borders of the village, to the southwest, stood one of the celebrated holy sites/pilgrimage destinations of Hayots Tsor, the Chapel (it had served as a monastery in the past) of Vart Badrig (7th century Armenian general, also known as Prince Vart Rshdouni, son of Theodoros Rshdouni). The primary festival day of this holy site was Vartavar Sunday (the Feast of Transfiguration). On that day, large crowds from the villages of Hayots Tsor would gather at the site, including a large number of youth [54].

Gem/Keopruler (Köprüler)

100 households, 547 Armenians.

The Saint Thaddeus Church (built of stone and mason, “apostle-built”) [55]. In the mid-1850s, the community had two serving priests. The remains of the Khntragadar Monastery were located to the north of the village [56].

Gezeltash (Garmrakar)/Kezeltash (Kızıltaş)

51 households, 314 Armenians.

The Holy All-Savior Church (built in 1858). In 1883, the name of the church was recorded as the Holy Trinity [57].

Gghzi/Gurpenar (Gürpınar)

44 households, 312 Armenians.

The Saint Daniel Church. The ruins of the Holy Virgin Monastery of Arghou was also in the vicinity of the village [58].

Hirdj

30 households, 205 Armenians.

According to records from 1858, the village church was called Saint Sdepanos (built of stone and mortar). According to records from the 1880s, the village church was called the Holy All-Savior [59].

Hntsdan/Erkalde (Erkaldı)

37 households, 209 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (built of stone and mortar). Records also mention another church operating in the village [60].

Mashdag/Geolkashe (Gölkaşı)

64 households, 394 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest [61].

Marks/Andach (Andaç)

20 households, 170 Armenians.

The Saint Minas Church (built in 1858). On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the church was known as Saint Mardiros [62].

Moulk

7 households, 33 Armenians.

The Holy Virgin Church [63].

Norkegh/Chakenle (Çakınlı)

88 households, 513 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest [64].

Vochkhrants/Koyounyataghe (Koyunyatağı)

11 households, 67 Armenians.

The village did not have a church. About half an hour’s distance southeast of the village stood the dilapidated Saint Adom Chapel, which was a pilgrimage destination for infertile women [65].

Upper Bjngerd (Mjngerd)/Youkarekaymaz (Yukarıkaymaz)

7 households, 53 Armenians.

The Saint Tovma Church [66].

Bltends/Aladuz (Aladüz)

65 households, 386 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar). In the mid-1850s, the community had one serving priest [67]. The ruins of the Saint Hovhannes Monastery were located to the south of the village [68].

Saint Vartan/Keyedjak (Kıyıcak)

18 households, 114 Armenians.

The Saint Vartan Church (roof built of wood) [69]. The village was named after the “beautiful and grand” Saint Vartan Monastery, located nearby on the shores of Lake Van. In the 1760s, the monastery was submerged as a result of rising water levels of the lake [70].

Karvants/Chayerbashe (Çayırbaşı)

2 households, 14 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (in half-ruins) [71].

Kerdz/Abale (Abalı)

104 households, 637 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (built of stone and mortar) [72].

Keoshg/Yenikeoshg (Yeniköşk)

40 households, 232 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (built of stone and mortar) [73].

[1] Ashkhadank Weekly, Van, March 20, 1911, N. 10, pages 5-6 (274-275), N. 11 (March 27), pages 4-6 (289-291).

[2] Y. Lalayan, “Vasbouragan. Nshanavor Vanker” [Vasbouragan: Renowned Monasteries], Azkakgragan Hantes [Ethnographic Review], Tbilisi, 1911, Book XXI, page 100.

[3] S. Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, Research on Armenian Architecture (RAA) Fund, 2018, page 50.

[4] K. Sherents, Srpavayrer. Deghakroutyun Vasbouragani-Vana Nahanki Klkhavor Yegeghetsyats, Vanoreyits yev Ousoumnaranats [Holy Sites. Geography of the Most Significant Churches, Monasteries, and Educational Institutions of Van-Vasbouragan], Tbilisi, 1902, page 99; H. Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere [The Monasteries of Vasbouragan-Van], Part C, Vienna, Mkhitarine Press, 1940, page 748.

[5] Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part C, page 748.

[6] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 100.

[7] Ibid., pages 99-100.

[8] Y. Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun Partsr Hayk yev Vasbouragan 1872-1873 [Travels in Upper Hayk and Vasbouragan 1872-1873], Yerevan, History Institute of the Academy of Science of Armenia, 1991, page 280.

[9] Thus, K. Sherents (in 1902) states that the administration of the monastery was entrusted to the Der Kevorkian family of Ankgh, and that the family’s representative also served as the monastery’s priest (Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 99). According to Y. Lalayan (in 1910), the monastery was administered by the priest of Ankgh (Lalayan, Azkakgragan Hantes, Book XXI, page 100).

[10] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 10, pages 5-6 (274-275). For additional details on the monastery, see Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, pages 46-51.

[11] Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, Book XXI, page 56; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 77.

[12] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 100.

[13] Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, Book XXI, page 56; Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankere, Part C, page 757.

[14] Lalayan, Azkakragan Hantes, Book XXI, page 56.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 101.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 82.

[19] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290).

[20] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 114.

[21] M. Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Kavars Arevelyan Dadjgasdani. Deghagroutyunk Saren yev Tsoren, Hnen yev Noren Bidani Kidnots [Descriptive Chronicle of Travels to Armenian-populated Provinces of the Eastern Ottoman Empire. Reports and Practical Information on Mountains and Valleys, on the Old and the New], Part A, M.G. Sareyan Press, 1884, page 141.

[22] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 4 (289).

[23] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 114. For additional details on the buildings of the monastery compound, see the same source, pages 118-123.

[24] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, page 140.

[25] Ararad, 1896, E, page 247.

[26] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 4 (289).

[27] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, page 164.

[28] Ararad, 1896, B, page 88; E, page 247.

[29] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 4 (289).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 100; Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 4 (289).

[32] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 4 (289).

[33] Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun…, page 172.

[34] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, page 165.

[35] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 103.

[36] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 42; Hayots Tseghasbanoutyune Osmanian Tourkiayoum: Verabradznerou Vgayoutyunner: Pasdatghteri Joghovadzou [The Genocide of Armenians in Ottoman Turkey: Testimonies of Survivors: Anthology of Documents], Volume I, Van Province, Yerevan, Armenian National Archives, 2012, page 152.

[37] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 53.

[38] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 55.

[39] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290).

[40] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, pages 160-161; Archbishop D. Balian, Hay Vanorayk [Armenian Monasteries], Echmiadzin, 2008, page 262.

[41] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290); Garbedian, Hayots Tsor, page 60.

[42] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 60.

[43] For additional details on the fort, see Garbedian, Hayots Tsor, pages 63-71.

[44] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 145 (Haradents).

[45] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 77

[46] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, pages 87-91.

[47] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 93

[48] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290); Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 93.

[49] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 98.

[50] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 104; K. Patalian, Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan Ngarakire Medz Yegherni Nakhorein. Mas Arachin: Vani Vilayeti Gendronagan, Husisayin, yev Arevelyan Kavarnere” [“The Historical-Ethnographic Character of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide. First Part: The Central, Northern, and Eastern Provinces of the Van Vilayet”], VEMPan-Armenian Journal, Year 7 (13), Number 2 (50), April-June 2015, page 119.

[51] Arevelyan Mamoul, Smyrna, December 1879, page 364.

[52] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, Part A, page 184; Garbedian, Hayots Tsor, page 105.

[53] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 109.

[54] Sherents, Srpavayrer…, page 98. For additional details on the chapel, see Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, pages 111-113.

[55] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 136.

[56] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290).

[57] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 127.

[58] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 141.

[59] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 150.

[60] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 158.

[61] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 165.

[62] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 168.

[63] Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan…”, page 119.

[64] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 182.

[65] Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290); Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 183.

[66] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364.

[67] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 173.

[68] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, pages 187-188.

[69] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 188.

[70] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun…, Part A, pages 123-124; Ashkhadank, 1911, Number 11, page 5 (290); Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 262.

[71] Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 196

[72] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 364; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, pages 203-204.

[73] Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1879, page 365; Karapetyan, Hayots Tsor, page 207.