Musa Dagh - Family Structure

Author: Vahram L. Shemmassian, 16/09/19 (Last modified16/09/19)

Marriage and Family Formation

Exogamy was the norm in family formation: a distance of “seven navels” of blood relations was kept to avoid genetically transmissible disorders from occurring. [1] As a rule, marriages were arranged. Parents knew best for their son, but obtained his consent after focusing on a suitable girl. They then conducted a background check on her and her family’s socioeconomic status, reputation, and physical/mental fitness. Eventually, before making any commitment, the girl’s family also inquired about their future son-in-law and his kin. These checks were more easily done in village-endogamous cases, where people knew each other rather well, than in village-exogamous ones, which were not too common. [2] Elopements took place occasionally when a boy and a girl were in love and her father opposed their union. [3] In case of legal recourse, the girl’s wish prevailed. [4] Girls commonly married in their teens and boys by their mid-twenties. In rare instances, especially when a girl’s material wealth or inheritance prospects exceeded those of the male suitor, she could be older than him. [5]

Generally speaking, asking for a girl’s hand in marriage and obtaining her family’s consent involved three visits to their house by a delegation representing the bachelor’s family. During the first visit, the priest/pastor, chairman of the parish council/church board, a village notable, and or an elder male member of the family made their intentions known. During the second visit, the team obtained verbal approval. The actual engagement took place during the third visit with both families participating. Festivities marked the occasion. While engaged, the couple could not meet privately or speak to one another even in the presence of others so as to maintain family “honor” or “dignity” and also keep a certain distance just in case things went wrong. [6]

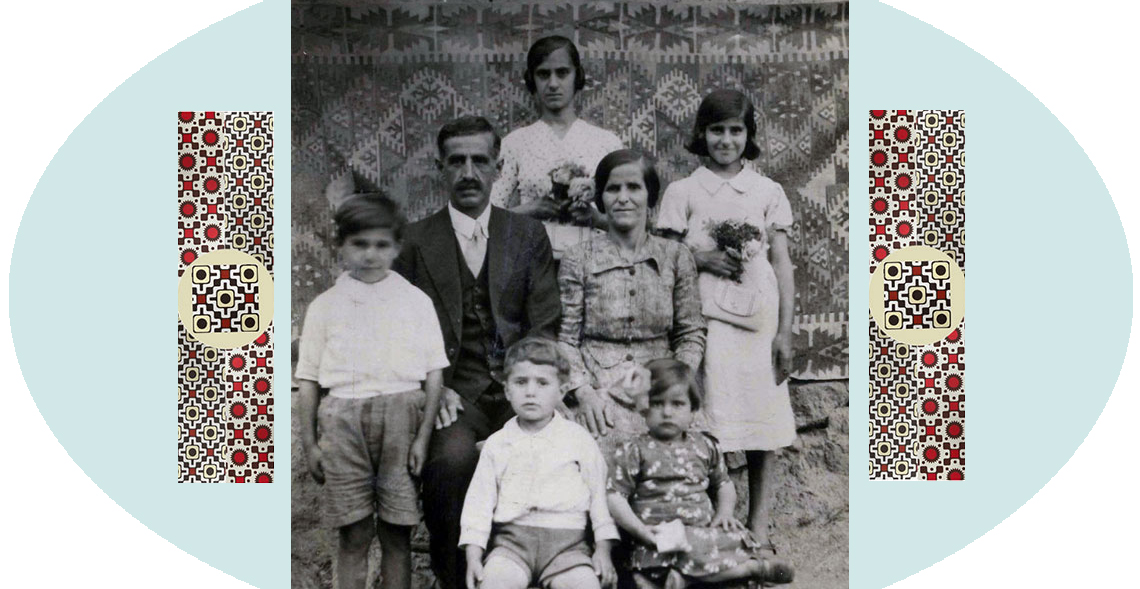

1) Wedding portrait of Nshan Boyajian of Kheder Beg and Ovsanna Filian of Bitias, 12 (or 21) October 1932, Kheder Beg? (Source: Vahram Shemmassian collection, Los Angeles).

2) Yesayi (after 1938 Fr. Movses) Shrikian and Negdar Bursalian wedding in 1923, Yoghunoluk (Source: Father Nareg Shirikian collection, Los Angeles. Courtesy of Liza Manoyan).

Weddings took place on Saturdays. Specially prepared foods and traditional music, songs, and dances enriched the celebration. The groom and godfather were dressed by the igitbashi (leader of braves) and his informal voluntary association of village bachelors. A group of women, including unmarried women and newly-wed ladies, performed similar rituals at the bride’s house. A joyous procession marched from the groom’s house to the bride’s house, picked her up, and led her to the church, usually on a horse. As a rule, the bride’s parents did not attend the church service, the explanation being that they “mourned” her leaving their home to join another family. After the wedding ceremony, the groom’s relatives converged on his residence to continue the celebrations. Young women from the bride’s side carried the kumash (fabric) and other articles as part of her uzhed (dowry), while a man carried the heavier dowry chest. Before the couple’s entry into the house, the bride symbolically smashed a clay jar to dispel evil spirits. She also threw a pomegranate to the ground or at a wall in hopes of having as many children as the number of seeds that burst out. Festivities continued through Sunday. The honeymoon took place at the husband’s house (traveling to a preferred or exotic destination was an unknown luxury). Celebratory gunshots fired in the air signaled the bride’s virginity at the time of marriage (the method of verifying virginity is not specified), thereby satisfying both families that their honor remained unblemished. [7] Last but not least, only death could separate a couple; divorce was virtually unheard of. [8]

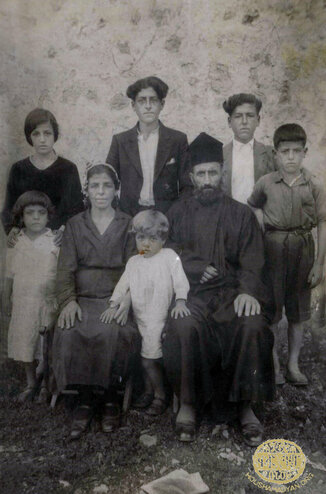

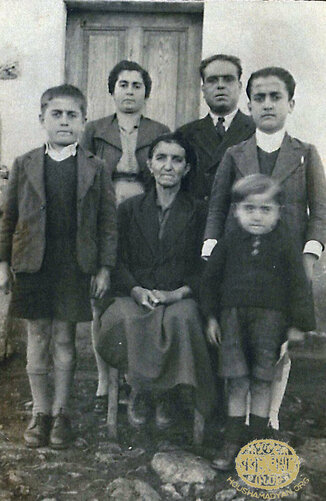

1) The family of Fr. Vahan (baptismal name Sarkis) Kendirjian of Bitias, mid-to-late 1930s (Source: Vahram Shemmassian collection, Los Angeles).

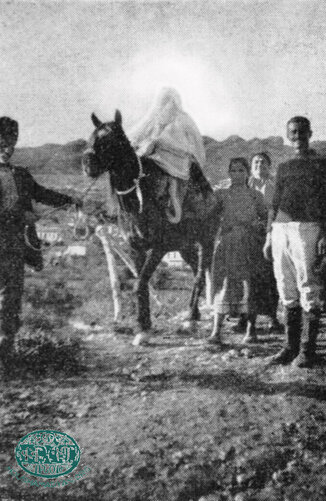

2) A wedding procession in Musa Dagh, place and date unknown (Source: Mardiros Kushakjian and Boghos Madurian, eds., Hushamadian Musa Leran [Memorial Book of Musa Dagh] (Beirut: Atlas press, 1970).

3) Nshan and Ovsanna Filian Boyajian family of Kheder Beg, 1930s (Source: Vahram Shemmassian collection, Los Angeles).

Births and Family Size

Children were expected to be born within the first year of marriage. Traditional treatments, sometimes mixed with folkloric rituals, were employed in case a woman did not become pregnant. But divorce was not an option even if all conception methods failed. People preferred to have a boy as their first child, for two reasons: to continue the family name and to have an economic helping hand. The first male and female children were invariably named after their paternal grandfather and grandmother. Boys and girls were raised differently after a certain age. In the case of boys, emphasis was placed on hard work so that they could support their families in the future. In the case of girls, childhood was a time for learning how to become good housewives. That is why, generally speaking, girls’ formal schooling was not considered as important, [9] although that mentality had begun to change.

By all indications, family size in Musa Dagh was not big. Three surveys bear out this fact. To begin with, the average family size in each village based on a 1929 population count was as follows: Bitias, 5.05; Haji Habibli, 4.4; Yoghunoluk, 5; Kheder Beg, 4.83; Vakef, 5.4; Kabusiye, 5, for an average of 4.94. [10] Second, a survey conducted sometime in 1939 in preparation for the exodus revealed the following figures (unfortunately those of Yoghunoluk and Vakef are not available): Bitias, 278 heads of households, 946 family members. Listed under “head of household” were 63 bachelors (mostly) and unmarried women (and perhaps a few old widows and widowers) with no family members of their own indicated. Therefore, the actual number of heads of households was 215 and the average family size was 4.33, 10 being the largest size. In Haji Habibli, there were 207 heads of households with a total of 909 members, for an average of 4.39 members, 11 being the largest size. In Kheder Beg: 217 heads of households, 1,037 members, 4.77 average household size, 11 being the largest size. In Kabusiye: 184 heads of households, 890 members, 4.83 average household size, 9 being the largest size. To summarize, household size in those four villages varied between 4.33 and 4.83 members, for an average of 4.58 members. (See appendices).

Third, a 22 August 1939 French survey conducted at the Ras al-Basit encampment yielded the following results: Bitias: 228 families, 982 individuals, 4.3 individuals/family (the averages are mine); Haji Habibli: 215 families, 909 individuals, 4.22 individuals/family; Yoghunoluk: 236 families, 886 individuals, 3.75 individuals/family; Kheder Beg: 243 families, 1,082 individuals, 4.45 individuals/family; Vakef: 89 families, 368 individuals, 4.13 individuals/family; Kabusiye: 193 families, 898 individuals, 4.65 individuals/family. [11] Therefore, family size varied between 3.75 and 4.65 individuals, for an average of 4.25 individuals per family. To conclude, although there are differences among the averages of the three surveys, they still indicate that family size in Musa Dagh was small, under five members per family. Unfortunately, we do not have concrete evidence as to the number of families living together under the same roof, although there is a hint to that effect in the section on housing above.

Inner-Family Relations

Husband-wife relationships, and the social status of men and women in general, differed to some extent depending on location and religious denomination. The Musa Dagh villages could be divided into two groups for our purposes: Group 1: Yoghunoluk, Kheder Beg, Vakef, Kabusiye; Group 2: Bitias and Haji Habibli. In Group 1, there was marked inequality between the two genders. Men made the important decisions and gave the orders, while women had to obey without questioning them. However, women, not men, carried heavy loads of wood and bushes, as well as water from the springs. Men did not even carry their children in public, considering it inappropriate, if not shameful. [12] Although women shouldered a heavier burden than men in terms of house chores, child rearing, and economic contribution, their duties were not acknowledged or appreciated by society at large. If a couple went out together for some reason, they walked separately, with the wife trailing behind. At the Apostolic Church, men occupied the front section, followed by elderly women in the middle and younger ones at the far end near the entrance. [13]

In Group 2, women felt less constrained by traditional, conservative dictates. Within the Protestant community especially, they were more outspoken in their views. Husbands were less controlling and more respectful towards their spouses. Married couples usually walked next to each other on outings, sometimes even arm-in-arm. No less burdened with heavy labor than women elsewhere, they were nevertheless recognized for their substantial contributions to family well-being. There certainly was physical separation between genders during church worship. But it was a parallel division, meaning, the men sat in the right pews and the women in the left pews facing the pulpit, thus not according to a front-back order. The Apostolic community in Bitias, while not as liberal, was influenced by the Protestants and therefore less conservative than its counterparts in Group 1. [14] The Haji Habibli community, although belonging almost entirely to the Apostolic Church, was quite similar to its Bitias coreligionists in terms of women’s status and gender relationships. This can be explained in part by the familial relationships that a number of people from both villages had, and by their proximity. [15] Information pertaining to man-woman relations and status in the smaller Catholic communities of Kheder Beg and Yoghunoluk is not available. However, it would be relatively safe to assume that Catholics were closer to conditions existing among their fellow Apostolic villagers.

With some exceptions, the husband in Group 1 did not speak with or refer to his wife by her first name. He instead called her meir (our), chujekhnen muar (the children’s mother), genag (wife/woman), ashgein (girl/daughter of… [father’s name]), etc. [16] In turn, the wife addressed or referred to her husband as mourt (man/husband) or meir mourt (our man/husband). Why? In the case of men, it was because expressing affection whether at home or in public, even by just mentioning the wife’s Christian name, was considered shameful, or not uttering her name would affirm or reinforce his authority or superiority. In the case of women, they had to maintain the expected formality by addressing their spouses in the third person. [17] But in Bitias, both husband and wife called each other by their first names [18]—another manifestation of informality or open affection. This, and some of the above phenomena, could be explained by the many decades of exposure to American Protestant missionary liberalism, at least compared to Musa Dagh conservatism, [19] and as an effect of the bourgeois lifestyles of summer vacationers.

An elaborate terminology identified the various family members including those of in-laws and godfather. Dud and mar denoted father and mother, respectively. Babag was the designation for paternal as well as maternal grandfather. But “grandmother” was treated differently. While dadimar literally meant father’s mother, kiremar meant maternal uncle’s mother. In other words, maternal grandmother came to be known through her son rather than directly through her daughter. This can be viewed as yet another indication that Musa Dagh society was by and large patrilineal. The paternal uncle was amma, whereas his wife was called aghpergen, that is, (father’s) brother’s spouse. Hurker/hurkayr was paternal aunt and hurkerar her husband. Kira was maternal uncle and kiregen his wife. Murker/murkayr was maternal aunt and murkerar her husband. A woman’s father-in-law and mother-in-law were known as (e)sgsrar and (e)sgiseur, whereas a man’s father-in-law and mother-in-law were called kayenbaba and kaynana. The word for husband’s brother was dakrari and that for his wife nirdigen. The husband’s sister was dul or daldigen, but no particular name, it seems, existed for her husband. On the other hand, the wife’s brother was keina. A man’s family called his wife hurs (bride/daughter-in-law) and their daughter’s husband piso (groom/son-in-law). Siblings and cousins called each other aghpar (brother) and kayr/kureug (sister). A grandchild of either sex was turen. As for godfather, he was addressed as bub, his wife as mum, mother as babumar, and sister as babuker. Strangely, here too the bub’s father and brother did not have particular designations. However, the godfather’s entire family was respectfully addressed as babenk. People followed in-law- and godfather-related protocols attentively, as reciprocal invitations, visits, and/or gift exchanges took place on special family occasions and religious holidays. [20]

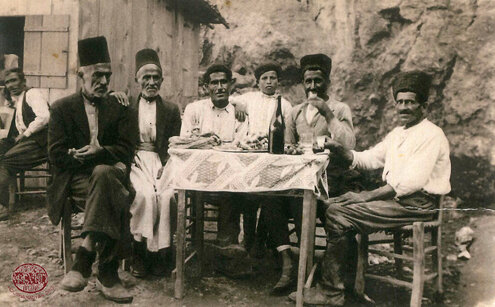

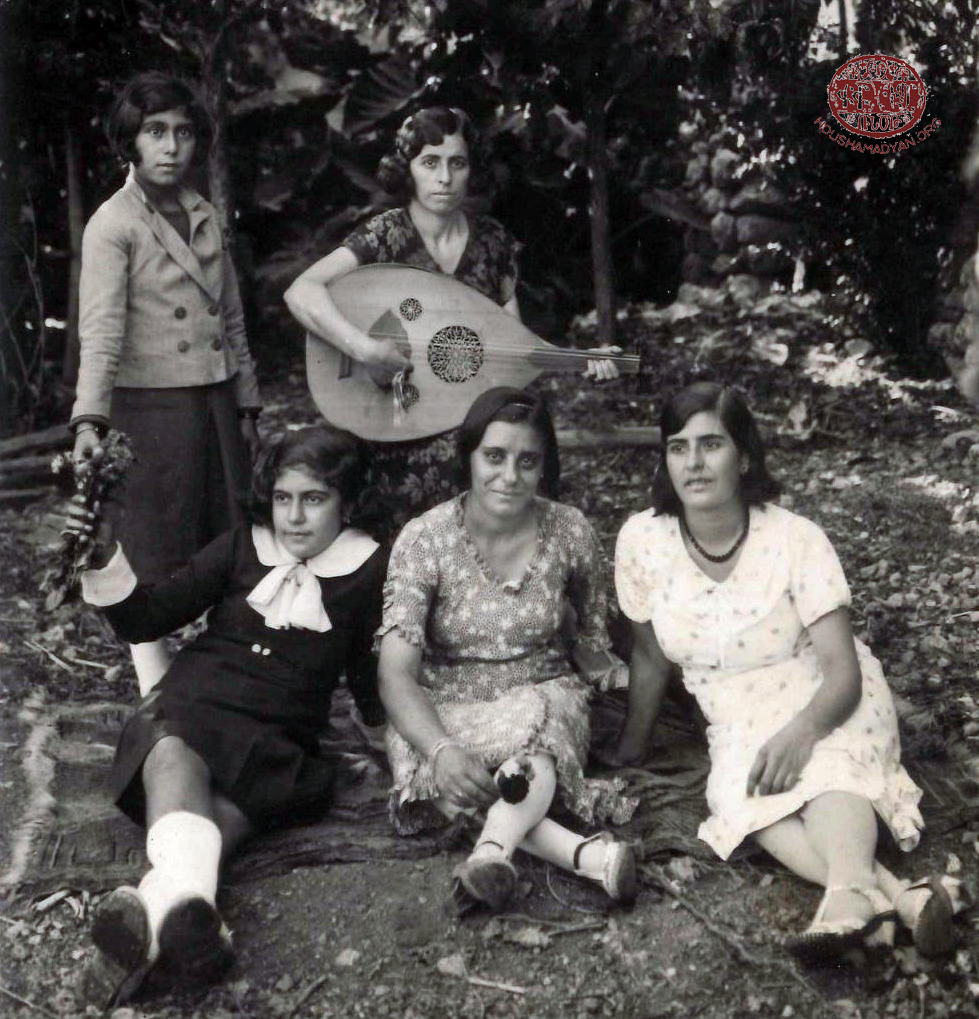

Yard of Kevork ("Aziz") Sherbetjian's residence, his family, and guests, 1930s, Bitias.

Seated L to R: Suren Papakhian, a Darontsi teacher at the Bitias national school and later Fr. Suren Papakhian of St. Sarkis Church of Detroit, Michigan; Kevork ("Aziz") Sherbetjian; his wife, Varter nee Maghzanian; son-in-law Yesayi Stambulian; youngest daughter Zekiye.

Stanting L to R: Mari Sherbetjian, another daughter; a certain Maghzanian, a relative; Jemile Sherbetjian Stambulian, a daughter and Yesayi's wife; Hagop Simoni (Dasnabedian), future ARF leader Hrach Dasnabedian's uncle (Source: Vahram Shemmassian collection, Los Angeles).

Surnames

Musa Daghian surnames, which may be divided into six main categories, constituted additional indicators of social roles, status or relationships. To begin with, a significant number of families identified themselves by the first name of a founding ancestor or patriarch plus the “ian” Armenian suffix, in this case meaning “descendent of.” Thus, Tovmasian, Torosian, Matosian, Antreasian, Mikaelian, Aprahamian, Andonian, Nigoghosian, Melidonian, Isgenderian, and so on. Because some families hailed from priestly background, they added the Der (Father/Lord) title to their surname: Der Kalusdian, Der Bedrosian, Der Hovhannesian, Der Arakelian. Second, a tangible fraction of last names revealed the bearers’ geographical origin, such as Bolisian (from Constantinople), Stambulian (from Istanbul), Izmirlian (from Izmir/Smyrna), Bursalian (from Bursa), Aintabian (from Aintab), Urfalian (from Urfa), Kebreslian (from Cyprus), and Kesablian (from Kesab). [21] In other words, the Musa Dagh community comprised a mixture of people from different places, whose forebears had migrated to or taken refuge in Musa Dagh for various reasons, thereby adding to a presumed original core which must have existed since antiquity.

In the third place, certain surnames hinted at occupations. This category included the Boyajians (painter), Kushakjians (maker/seller of girdles), Berberians (barber), Kuyumjians (goldsmith), Demirjians (ironsmith), Tenekejians (tinsmith), Kazanjians (cauldron maker), Keoshkerians (shoemaker/cobbler), Sherbetjians (juice seller), Kadeian (judge), Kassamanian (tax distributor/divider), etc. To be sure, the 1920s-1930s generation, that is, those who had such family names, did not necessarily practice the stated professions; rather, they carried on those personal identifiers bequeathed to them by previous generations. The same category of surnames also indicated some types of official religious role, for example, Zhamgochian (church bell sounder/assistant to the priest) and Shemmassian (deacon). Fourth, the peculiar physical feature and/or ability of an ancestor determined a last name (evidently evolving from a nickname). For instance, the Filians (elephant) were so called because of their huskiness; the Jambazians (acrobat) demonstrated agility; the Tilkians (fox) either resembled or acted like that wily animal; the Kerkezians (vulture) were somehow associated with that ravenous bird, etc. Fifth, honorific titles formed a few surnames, such as Begian (sir/country gentleman), Aghaian (notable), Efendiian (educated gentleman/high-ranking Ottoman personage), and Pashaian (highest title of Ottoman and military officers). Whether they truly testified to the bearers’ high rank (in the Ottoman era) cannot be readily determined. And the sixth category of last names consisted of a potpourri of designations, some explicable, others not. [22]

1) Daughters and one granddaughter of Kevork (“Aziz”) and Varter Maghzanian Sherbetjian of Bitias, early 1920s. Front row, L-R: Zakiyé (holding a chicken), Jamilé (holding a white, handmade doll), Mary Shemmassian (holding a cat; she later married Hovhannes Bursalian of Yoghunoluk). Back row, L-R: Mary (Sherbetjian), Marta (Sherbetjian, married to Kapriel/Jabra Shemmassian of Yoghunoluk and mother of Mary standing in front of her). (Source: Vahram Shemmassian Collection, Los Angeles).

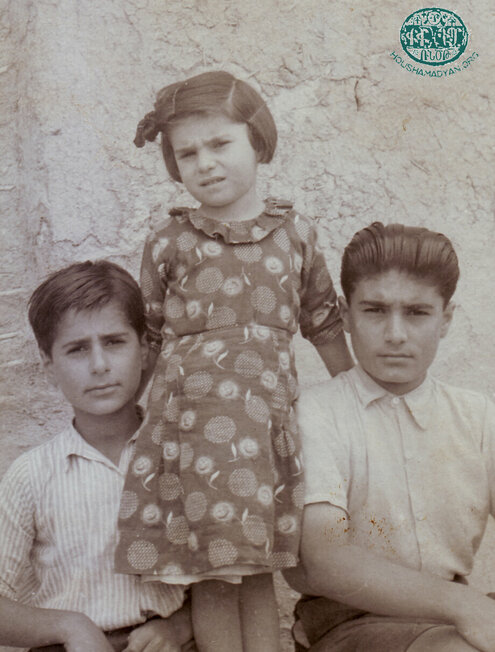

2) Children of Fr. Movses and Negtar Burasalian Shrikian of Yoghunoluk, 1938: Herminé (center) with her brothers Pailag (left), who later became Fr. Goriun and served the St. Sarkis Armenian Apostolic Church of Detroit, Michigan, and Kevork (right), who later became Fr. Nareg and served the St. Paul Church in Anjar, Lebanon, and subsequently several Armenian Apostolic churches in California, USA. They had two more siblings (not pictured): Sosen (m. Nazaret Bidanian), and Kurken (Source: Father Nareg Shrikian collection, Los Angeles. Courtesy of Liza Manoyan).

A number of families had the same roots, but carried different surnames. There are two explanations for this phenomenon. The first deals with size. As families in time grew larger, some heads of households decided to adopt their father’s or immediate grandfather’s name as last name to avoid confusion. In some of these cases nicknames offered a practical solution, as explained by Bitias native Alberta Magzanian:

"Some may dismiss nicknames as a frivolous topic, but not in a place where people were known by their nicknames and not any given names. Besides, in a small community where there is a tradition of naming one’s first born after a grandparent, within a couple of generations, one may end with multiple Hagops, Annas, Musas, Maries, etc. Nicknames were creative and solved many identity problems. In some instances, the nickname was adopted as the new family name - a challenge for people who want to trace their genealogy, an issue I am sure did not concern those who made the change. Our family name, Magzanian name, still wanted to go their separate ways. For instance, the original Stambulian split with some family members in Bitias becoming Keshishian"[23].

1) Bitias: Fixed Property Ownership, 1939

2) Bitias: Animals and Weight of Other Movable Properties, 1939

3) Haji Habibli: Inhabitants, Animals, and Value of Fixed Properties, 1939

4) Kheder Beg: Inhabitants, Animals, and Value of Fixed Properties, 1939

5) Kabusiye: Inhabitants, Animals, and Value of Fixed Properties, 1939

The first and last names have been spelled as they appear in the original document. To view a PDF of all pages, click on the photographs above.

Ethiopia-born Hagop Atamian explains the reason behind the Atamian-Chemenian division in Yoghunoluk:

"My grandfather was Khatcher, son of Hagop. Khatcher changed his name from Atamian to Chemenian. According to my aunt's stories, letters, etc. which my father used to send to his father from Ethiopia sometimes reached the other Khatcher Atamian (his cousin??) by mistake. So my grandfather apparently got angry about this and decided to change his name to Chemenian (it is said he liked to eat chemen [a spicy seasoning]). So, part of my dad's family subsequently became Chemenian". [24]

The second reason emanated from a desire to Armenise the family name from its original Turkish version. Such was the case, for instance, of the Keshishians (priest in Turkish) and Yeretsians and the Bayramians (holiday in Turkish) and Donigians, both sets of families being from Kabusiye. As these and other families over time splintered into multiple branches, they naturally transcended the traditional understanding of “extended family” as three generations living under the same roof. Hence, one would find in Musa Dagh, as in other societies, people claiming the same roots but with various last names, not just in the case of females (who would adopt their husbands’ names), but also males. [25]

It should also be noted that people with the same surname in different villages may or may not have been related. For instance, the Zobians in Haji Habibli and Bitias claimed common ancestry. Because Kheder Beg and Vakef were offshoots of Yoghunoluk, their inhabitants with the same last name were usually related, for example, the Shemmassians of Yoghunoluk and Vakef and the Adajians of Yoghunoluk and Kheder Beg. On the other hand, the Mardirians of Haji Habibli, Kheder Beg, and Kabusiye, and the Sherbetjians of Bitias and Kheder Beg had no common bonds.

Nicknames

Parents named their children at birth, but people ascribed unofficial names to each other according to their preferences or perceptions. Locally referred to as laghabu (laqab in Arabic, meaning, title/label), nicknames were usually given not during childhood, but rather after adolescence, when a person had formed his distinct personality and/or lived long enough to be recognized by a distinctive feature. No adult male (or some women), it seems, was immune to this practice. That the phenomenon of labeling was prevalent and deeply rooted in Musa Dagh society was underscored by the fact that peoples’ actual names/surnames were sometimes, if not often, forgotten as they were supplanted by nicknames commonly used in everyday life. [26]

Various factors determined nicknames. To begin with, they described individuals based on their origins or histories. A lad orphaned as a result of the 1909 massacres in Antioch and subsequently relocated to Bitias for safety became known as Antakalen (the Antiochian). Krikor Arushian, a baker in Bitias, and his family were referred to as Urfatsink (hailing from Urfa). [27] An expatriate in the United States who returned to his native Yoghunoluk after World War I was recognized as Amirikitsen (The American), and so on. [28]

A certain activity, behavior or manner figured prominently in giving informal names. Uchereb, a corruption of the Turkish-Arabic compound word meaning “three-quarters” (in this case, of 1 lira), was a man who charged that amount when purchasing orders for fellow villagers in Antioch. Tahtelbahar, another compound Arabic word, meaning “under the sea,” dove into the Buyuk Karachay to catch fish. Pst walked quietly like a cat. Kute Charek, meaning, “bad shoe” in Turkish, was a thief. Kambuza prepared an eponymous onion dish. Tk-tk used to knock on doors in his childhood. Keklik imitated the sound of a partridge. An old woman called Atash Nana worked hard and fast like a consuming fire. [29] Khuruzink were known as such, because their family patriarch, Sarkis Igarian, did two things: first, every time that he finished building a house, he climbed to the roof and crowed like a rooster as a sign of accomplishment; second, he organized and/or enjoyed cock fights. [30] A man who gossiped became known as Fesfes. [31]

Looks also captured the attention of name givers. Kallash was bald. Ashkar had blond hair. Ingiliz looked fair like an Englishman. Ezghir’s (Arabic word) body was small, and so was Petit Vanis’s. Kerraj had remained diminutive. Ishnunink (derived from the local Armenian word ishsheunk, i.e., fall), appeared pale and exposed like a leafless tree in autumn. Saba and Dkhruni resembled a Greek merchant from Antioch and a Social Democrat Hnchagian (SDHP) leader called Sarkis Dkhruni (Kederian), respectively. Kartaloghlan comported himself in a proud manner like an eagle. [32] Garmer’s (red) face radiated that color; it also betrayed the man’s Communist orientation. [33]

People with physical/mental impairments did not escape comment. Gayr (blind), Shashgah (cross-eyed), Kheul (deaf), Tupal (lame), Chulakh (crippled hand), Garj (short), Kheiv (fool), and other adjectives were given unabashedly. Certain unsavory acts likewise created nicknames, but these were few and far between. Character (stinginess), one’s nature (melancholic), occupation (butcher, clairvoyant), miscellaneous other nicknames, and weird, inexplicable designations also made the list. [34]

Something said by someone, whether just once or repeatedly, would be cause to affix a nickname to that person for life. Magzanian elaborates her mother’s case:

"The majority of the male inhabitants of Bitias may have earned nicknames in their life time, but the same cannot be said of the women. There were, however, a few exceptions, such as…our mother Victoria Chaparian Magzanian. At a young age, our mother acquired the nickname Keleshum and she retained it throughout her life. When mother was about four years old, she accompanied her Chaparian cousins to a picnic at the outskirts of the village to gather manigh, a wild edible weed. While the older Chaparians were digging up the plants, it seems mother collected some of their harvests and took it to an elderly woman from the village of Yoghun Oluk. The lady was delighted by her action and addressed her by the following words,“Keleshum, chuts el aghveur lortch itchvinir gunna.”Translated from the dialect into “pretty one, you have such pretty blue eyes.” That did it! On their way back home, the cousins took turns carrying her almost as a trophy on their shoulders and, of course constantly addressing her as Keleshum". [35]

Another person from Bitias was called Khashdag (a corruption of the Arabic word for “enough”) because he used that term profusely. In fact, the entire family became known as Khashdagink. Kevork Sherbetjian carried the label of Aziz (dear) for his sweet talk and addressing his fiancée as such. A man greeting others with the Arabic marhaba (hello) acquired the nickname Mahrabe. When asked what he was up to, a farmhand replied, “eqlebo,” meaning, turning the soil upside down. So people nicknamed him Eqlebo. [36] A villager from Vakef was anointed Jsd-Vsd because he repeatedly said “jsd-vsd alright” when supposedly “answering” a visiting Englishman’s questions. [37] The list goes on.

Defying life’s unfairness in terms of low socioeconomic status constituted yet another nickname determinant. This was particularly—and perhaps uniquely—true in the case of the inhabitants of the Vire Teugh neighborhood of Yoghunoluk, who counted among the have-nots. Demonstrating a sense of acceptance mixed with humor, they mocked poverty by bestowing honorific titles on each other. Thus, a poor man was agha, a poorer man pasha, and the poorest man efendi. [38]

The village notables were the unquestioned aghas or barins/bariuns (barons). Even if in rare cases there was a necessity for another nickname, still it would be applied in conjunction with the honorific title, for example, Sallan Bariun (Yesayi Aprahamian of Kheder Beg). Movses Der Kalusdian, on the other hand, arguably the most dominant figure in post-World War I Musa Dagh politics, was referred to as the Efendi. As for clergymen of the three denominations (Apostolic, Catholic, Protestant), they were addressed by their proper titles. Fr. Hagop Kelemian, one of the Apostolic priests in Haji Habibli, was additionally referred to as Der Hmbalus (Father Myrtle), perhaps for his excessive craving for that fruit. Similarly, parishioners at Vakef branded a non-native priest as Char (naughty/evil) for his selfish, worldly lifestyle. [39]

Unknown to the public at large, nicknames in the form of noms de guerre were adopted by members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) for exclusive, insider, clandestine use. Several categories of fictitious names existed. Some were derived from nature, denoting toughness and/or ferociousness: sar (mountain); zhayr/abarazh (rock); gaydzag/paylag/shant (lightning); hur (fire); yergat (iron). Others were selected from the animal kingdom, manifesting combativeness, peace, and beauty: ariudz (lion), kayl (wolf), varaz (wild boar); ardziv (eagle), paze/shahan (hawk); dadrag (dove); sokhag (nightingale). Still others were adaptations of the first names of Armenian political and military leaders, freedom fighters, and ancient pagan gods: Arshag, Vartan, Vahram, Vahan, Mushegh, Smpad, Suren; Keri, Murad; Vahakn. Furthermore, a number contained the “uni” suffix that many nakharar (medieval Armenian feudal lord) dynasties carried as part of their surname: Peruni, Nerguni, Anmahuni. A mixture of other designations, including shorter versions of common names as well as strange, inexplicable names, completed the catalog of noms de guerre. [40] Social Democrat Hnchagian Party members may also have followed this tradition of using pseudonyms, but hard evidence is lacking.

The nicknaming practices of Musa Daghians revealed the character of the people. First, they indicated strong imagination, a characteristic that must have been acquired from nature and from the unhindered freedom of thought that nature afforded, in addition to innate ability. Second, they indicated an acute awareness of the social and physical environment. Being highly perceptive, nothing seemed to escape their eyes (and ears). In this, they described their observations quite accurately. Third, their crudeness did not spare people with physical shortcomings; little consideration was given to human sensitivities, and causing psychological damage did not seem to matter. Fourth, they generally showed respect towards clergymen, educators, and other notables. Fifth, they did not mince words; they were straightforward and unabashed. Sixth, they demonstrated an uninhibited sense of humor. Seventh, they mocked life with all its socioeconomic inequalities. They, in short, reflected characteristics, some positive and some negative, not much different especially from others living in challenging environments.

- [1] Krikor Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune (The Ethnography of Musa Dagh) (Yerevan: National Academy of Sciences of the Republic Armenia “Kidutyun” Publishing House, 2001), p. 149.

- [2] Ibid., p. 150.

- [3] Shushanig Chaparian Papakhian, unpublished memoirs, Detroit, Michigan, p. 57.

- [4] Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, p. 149.

- [5] Ibid., pp. 148-49.

- [6] Ibid., pp. 151-52; Fr. Movses Shrikian, “Hushakrutiun Movses A. khn. Shrikiani (Avazanin Anun, Yesayi)” (Memoirs of Archpriest Movses Shrikian [Baptismal Name, Yesayi]), unpublished memoirs, Montebello, California, p. 69; Mardiros Kushakjian and Boghos Madurian, eds., Hushamadian Musa Leran (Memorial Book of Musa Dagh) (Beirut: Atlas Press, 1970), pp. 163-65.

- [7] Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, pp. 202, 153-67; Kushakjian and Madurian, Hushamadian, pp. 166-70. See also Fr. Shrikian, “Hushakrutiun,” p. 70.

- [8] Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, pp. 147, 149.

- [9] Ibid., pp. 167-74.

- [10] Hayrenik (Fatherland) (Boston), 2 November 1929.

- [11] France, AMAE, E-Levant, Syrie-Liban, 1930-1940, Sandjak d’Alexandrette, Carton no. 530, telephone message from Bart (DELELATTA, i.e., Delegate at Latakia) to High Commissioner, Beirut, 22 August 1939.

- [12] Telephone interview with Vehanush Kuyumjian Bursalian, 25 September 2013, Granada Hills, California-Fresno, California; telephone interview with Sosen Shrikian Bidanian, 25 September 2013, Granada Hills, California-Fresno, California; Kushakjian and Madurian, Hushamadian, p. 170.

- [13] Telephone interview with Shrikian Bidanian. For the heavy work done by women, consult Khacher Madurian, “Mer Hatse,” in Kushakjian and Madurian, Hushamadian, pp. 148-58.

- [14] Telephone interview with Alberta Magzanian, Granada Hills, California-Olney, Maryland, 25 September 2013.

- [15] Ibid., 31 December 2013.

- [16] Telephone interview with Shrikian Bidanian; telephone interview with Kuyumjian Bursalian; Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, p. 144.

- [17] Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, p. 144; telephone interview with Shrikian Bidanian.

- [18] Telephone interview with Magzanian, 21 August 2013.

- [19] For the activity of American Protestant missionaries in Musa Dagh during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, see Vahram L. Shemmassian, “The Armenian Villagers of Musa Dagh: A Historical-Ethnographic Study, 1840-1915,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1996, pp. 81-98.

- [20] For family membership terminology, see Sima Aprahamian, “The Inhabitants of Haouch Moussa: From Stratified Society through Classlessness to the Re-Appearance of Social Classes,” Ph. D. Dissertation, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, 1989, pp. 72-3; Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, p. 144; interview with Isgender Nashalian, 1 July 1989, Glendale, California; interview with Rosine Shemmassian Kundakjian, 1 September 2013, San Carlos, California.

- [21] For surnames, see appendices 1-5. The names and surnames are listed as spelled in the original documents and therefore often differ from the spellings in the text.

- [22] Ibid. The translations/interpretations of names are mine.

- [23] Alberta Magzanian, lettere, 2 February 2011.

- [24] Hagop Atamian, email to the author, 15 December 2011.

- [25] Gyozalyan, Musa Leran Azkakrutyune, p. 141.

- [26] Interview with Movses Sarkis Sherbetjian, 6 January 2002, Thousand Oaks, California.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] Interview with Hovhannes Hajian, 5 January 1990, Hollywood, California.

- [29] Interview with Sherbetjian.

- [30] Telephone interview with Florence Igarian Harutiunian, 27 October 1991, Van Nuys, California-Glendale, California.

- [31] Sarkis Penenyan, Hushabadgerner Musa-Daghen yev Modig Antsialen (Memorial Scenes from Musa Dagh and the Recent Past) (Los Angeles, CA: Sarko Printing, 1983), p. 81.

- [32] Interview with Sherbetjian.

- [33] Penenyan, Hushabadgerner, pp. 73-4.

- [34] Interview with Hajian.

- [35] Magzanian, letter, 2 February 2011.

- [36] Interview with Sherbetjian.

- [37] Penenyan, Hushabadgerner, p. 13.

- [38] Tovmas Habeshian, Musa-Daghi Babenagan Artzakankner (Ancestral Echoes of Musa Dagh) (Beirut: Erepuni Press, 1986), pp. 204-06.

- [39] Penenyan, Hushabadgerner, pp. 70-1, 106.

- [40] Armenian Revolutionary Federation Archives, Boston (now in Watertown), Massachusetts, File 965/28, H.H.T Giligio gam Lernavayri G. Gomide 1921 t. (A.R.F. Cilicia or Lernavayr Central Committee 1921), the Roster of Kabusiye Comrades; untitled roster of Yoghunoluk comrades.