Karen Jeppe (1876-1935): “Mother of Armenians”

Authors: Matthias Bjørnlund & Elyse Semerdjian 10/08/20 (Last modified 10/08/20)

Karen Jeppe’s Early Life

A devout, but liberal Lutheran Christian from rural Denmark, Jeppe spent most of her adult life, a total of 30 years, in the Middle East as a teacher and relief worker whose work focused on Armenians. Her thinking, Keith Watenpaugh has argued, moved beyond missionary work; it was, indeed, at the forefront of modern humanitarianism that emerged before and during World War I. In fact, while Jeppe worked for and with Evangelical missionaries, she explicitly distanced herself from that designation - “missionary” - and from any attempts at proselytizing. [1] From the beginning to the end, she believed that the Armenian people could not survive persecution, genocide, and exile if they were not rooted in their own history, traditions, language, and Armenian Apostolic Christian religion. Of her efforts to rescue and resuscitate Islamized Armenian refugees in Aleppo, Jeppe wrote that the Armenian nation “should re-generate as the new bird Phoenix from the ash of the old one, it must be imbibed by the Armenian genius.” [2] With the mythical Phoenix, she could not have found a more fitting metaphor for the rebirth of a decimated people made possible, in part, by her own efforts to establish new communities for Armenians in post-war Syria.

A daughter of a schoolteacher in Gylling, Jutland, Jeppe too came to follow the footsteps of her father as a teacher, despite her father’s desire for her to become a doctor. He was a progressive local Christian intellectual who would read both Darwin and the Gospels to his daughter. He would also teach her Latin, German, French, Old Norse, and English, study nature with her on their long walks, and prompt her to read books from a young age about science, anatomy, and history. After studying mathematics at the University of Copenhagen without graduating (it apparently got too stressful), she became a full-time teacher at a modern, progressive school. Intellectually and emotionally it was a fulfilling position, but early in 1902 she went to a public event that changed her life. It was a powerful lecture delivered by Danish-Jewish-Icelandic ethnographer, humanitarian, and linguist Aage Meyer Benedictsen (1866-1927) detailing the plight of the Ottoman Armenians during and after the Hamidian Massacres (1894-1896), the devastating effects of which he had witnessed on a recent trip to the Ottoman Empire, Iran, and Russian Caucasus.

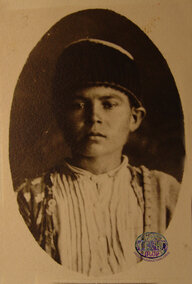

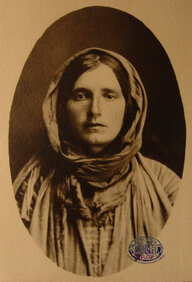

1) Karen Jeppe with one of the orphans of the Rescue House (Source: Bibliothèque Orientale – Université Saint-Joseph, Beirut).

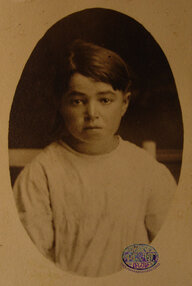

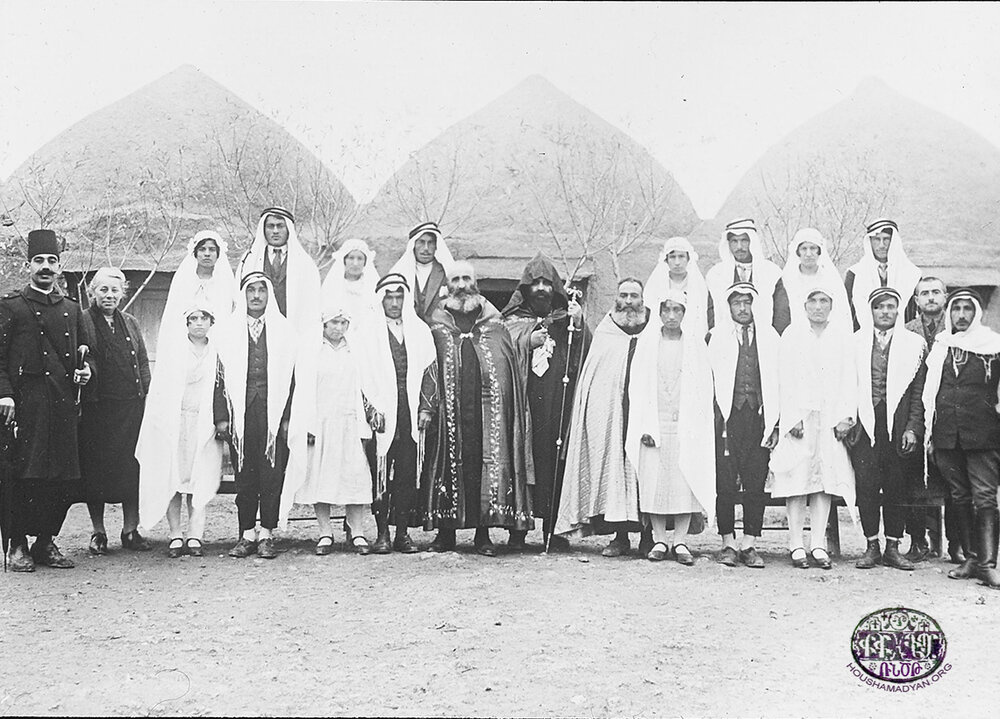

2) A photograph titled “Babo and wife” published in the Danish Armeniervennen newsletter for Danish Friends of Armenia. In the image, Babo clutches a photograph of his brother who lives in America under one arm and his unnamed wife in the other after a group wedding that took place in one of Jeppe’s Armenian colonies, Charb Bedros, under the direction of the Armenian Archbishop of Aleppo (Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Missak Kelechian).

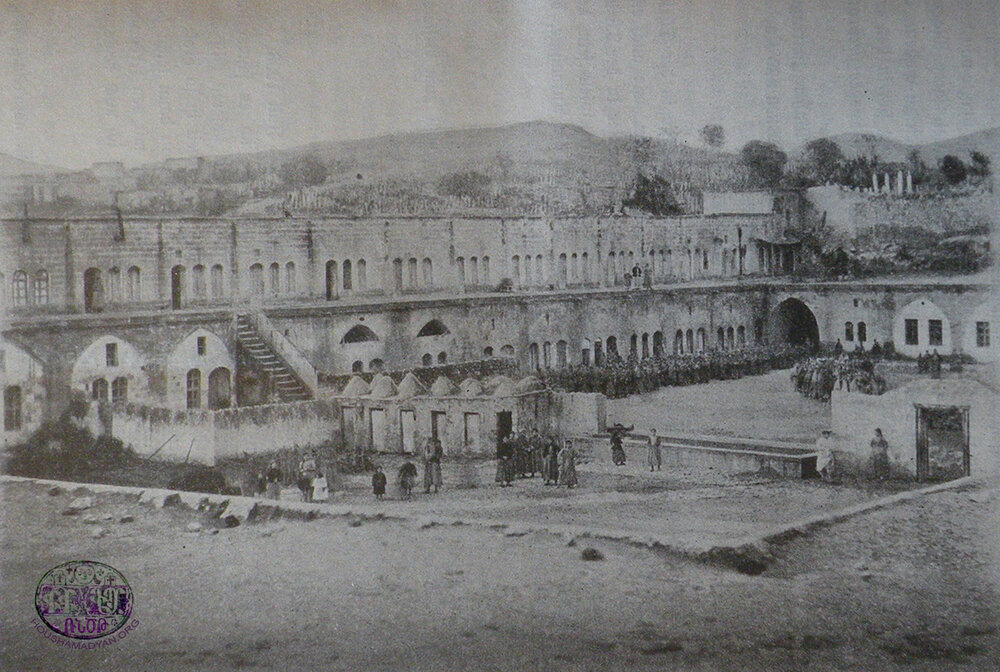

Jeppe and Benedictsen became friends, not least because they both wanted to do more for the Armenians than raising money and awareness. They wanted to help them in their homeland and discussed Jeppe working with them in the field. It is one thing to speak about such matters, though, quite another to actually go through with them. That day in 1902 at Benedictsen’s lecture Jeppe had received her calling to dedicate her life to the persecuted Armenians, as she told her priest, but until the first half 1903, she did not yet think she was ready to work in the Ottoman Empire. Benedictsen and his close and influential friend and collaborator, German theologian and Armenophile Johannes Lepsius (1858-1926), begged to differ, they were both confident that she already possessed unique and very useful talents. So, in November 1903, a mere year and a half after meeting Benedictsen, Jeppe agreed to travel with Swiss missionary Jakob Künzler to the Anatolian city of Ourfa (Şanlıurfa, Edessa), about 170 miles north of Aleppo. Here, Lepsius and his organization, the German Orient Mission (Deutsche Orient-Mission), had created an orphanage in a former caravanserai for a few hundred Armenians and was urgently looking for a teacher. [3] The newly-created Armenophile relief organization Danske Armeniervenner (Danish Friends of Armenians), the brainchild of Benedictsen and a group of likeminded Danes, paid her fare to the Ottoman Empire; Jeppe’s father paid for her equipment, though he was still opposed to her leaving, while the Germans paid her salary. [4]

Relief Work in Ourfa

Upon arrival, Jeppe and Künzler were greeted by legendary American missionary Corinna Shattuck, whose modern approaches to relief work, together with state-of-the-art Danish teaching methods, would become among Jeppe’s most valued initial sources of inspiration. Jeppe first immersed herself in the culture of Ourfa, learning the local languages: Turkish, Armenian, and Arabic. She also helped the manager of the German orphanage, Franz Eckart. After working there for eighteen months, she was ready to take charge of the orphanage that included ten boys sponsored by the DA organization that wired 125 kroners each per year for their care. [5] It was at Ourfa that her experimentation with a two-pronged education program—a modern curriculum combined with training in a skilled trade— took shape. This dual approach to education would also serve as the model for a commune she would later create in Aleppo after the war.

Managing an orphanage with up to 350 Armenian children, a staff led by Ohannes Effendi and his wife Tuma Hanum, as well as a kitchen, bakery, laundry, stables, workshops, classrooms, and dormitories was hard enough. But Karen Jeppe had come to work among an Ottoman Armenian population whose world had been broken. The massacres a few years earlier and the constant persecution were visible everywhere even on the landscape in Ourfa. Jeppe describes, for instance, how Corinna Shattuck pointed at a mound just outside the city gate where Armenian victims of the 1890s atrocities were buried in a mass grave. Indeed, the general Ottoman treatment of the Armenians amounted to “a slow war of extermination,” to use Aage Meyer Benedictsen’s term. But Jeppe also describes how the local Armenians never gave up, and how she found a life-long love of and symbiotic relationship with the Armenian people:

“I was filled with awe to find that the houses which 6-7 years ago were completely emptied of everything that humans need were now stocked with some household items and a certain amount of coziness [hygge]. Moreover, I saw the continuing oppression and exploitation of the Armenian element, an oppression that in itself ought to be more than enough to keep them in a state of misery and resignation. But instead they had, even under these circumstances, begun to stand up again and better their conditions. Now I not only pitied them, I admired them too. Despite centuries of oppression and slavery they kept the Holy Fire burning deep inside, and when I first got an eye for that, I forgot everything else.” [6]

1) Rescue Home children play in one of Karen Jeppe’s Ford automobiles used in rescue missions (Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

2) Karen Jeppe and her closest staff, known as “the Family,” in Aleppo, c. 1925. From top left: the married couples Leopold and Horome Gaszczyk and Lucia and Misak Melkonian. From bottom left: Jenny Jensen, Karen Jeppe, and the Danish women Karen Bjerre. Horome was a widowed survivor of the Armenian genocide married to Leopold Gaszczyk, an ethnic Polish officer posted with the Austrian-Hungarian Orient Korps to the Ottoman Empire during the latter phase of World War I. He both witnessed aspects of the genocide and briefly came to work for Near East Relief as a driver when he was decommissioned in 1919. He met his wife in Aleppo around 1920 and both came to work for Jeppe’s organization (Source: The Danish National Archives, Copenhagen, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

Jeppe’s connection with Armenians was firm indeed to the extent that she adopted two children from the orphanage—Lucia and Misak Melkonian—and more generally crossed socio-cultural boundaries that would have been unacceptable for any Armenian woman. During the genocide, when Armenian clergy were either killed or in hiding, she conducted an ecumenical mass and final rites for fallen Armenians in Ourfa, affirming that she could assume as an outsider and an unmarried woman the position of a priest. Her position allowed her to transgress gender norms and boundaries. Jeppe would, among other things, decry the effects of persecution on the Armenian people, their rank as second-rate citizens, and the unfortunate necessity of foreign involvement, such as the “foreign ideas” disseminated by her own organization as well as some missionaries. But she would still acknowledge with approval that the influx of these ideas could produce a positive side-effect for Armenian women in the realm of education and work opportunities.

“The Big Death” of 1915

In late 1915, during the extermination of the Armenians in Ourfa, Karen Jeppe stood by the window on the second floor of the house she was borrowing from Swiss doctor Andreas Vischer from the German Orient Mission. Swooning with fever and delirium from malaria and spotted typhus, overwhelmed with stress and heavy depression, Jeppe considered jumping. Downstairs, under the floorboards she kept twelve Armenians wanted by the Turkish authorities and in hiding from being captured. Among them were the businessman Bedros der Bedrossian, Kevork Garabedian, as well as the priest Der Karekin Voskerichian, his wife, their 15-year-old daughter, and their two youngest sons. The oldest son had been massacred like so many other Armenians while serving in the Ottoman Army. Initially, only men and boys were hiding in the house, because Jeppe and other foreigners had been led to believe that they could protect girls and women from deportation. That was not the case, the gendarmes came and took a group of them away from Jeppe’s house. A few were released after Jeppe and Künzler protested at the governor’s office, but most disappeared.

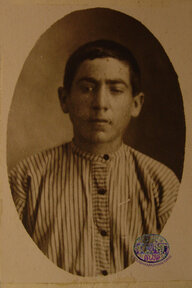

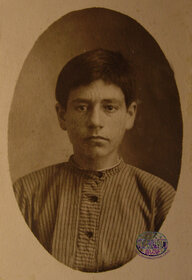

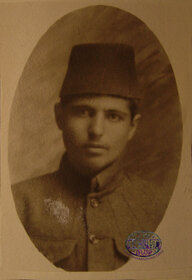

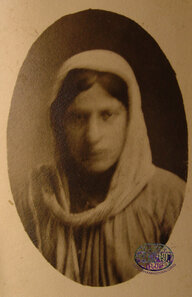

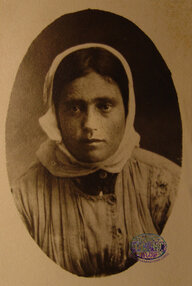

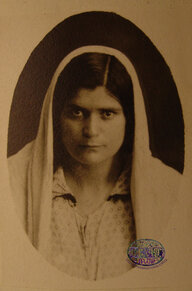

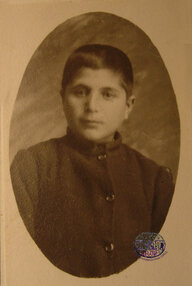

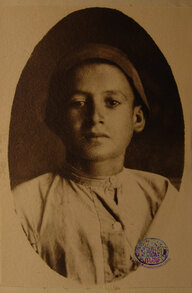

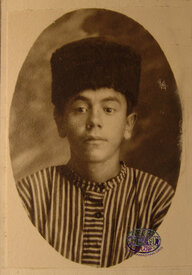

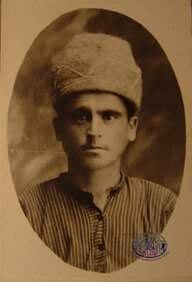

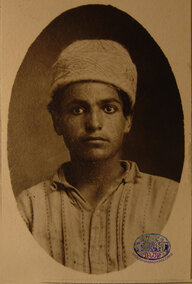

1) Sixteen-year-old Dikranouhi of Adana arrived at the home on September 18, 1925. Her father was disappeared during the initial deportations. She and her mother were taken in by a Kurd, but after her mother fell ill and died, Dikranouhi fled the house because the Kurd showed interest in marrying her. When she fled an Arab abducted her as his second wife. She found her way to Hassakah where one of Jeppe’s agents drove her by car to Aleppo. All rescued Armenians were immediately photographed in a studio next to a prop fence or bannister at the Rescue Home. From there, they were taken into a reception area where their information and biographies were entered into a register. A cropped version of this photograph pasted on entry number 820 (Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

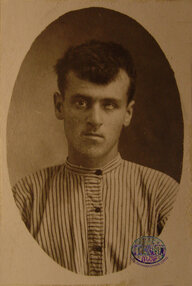

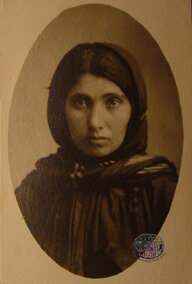

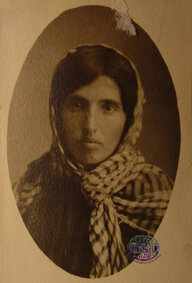

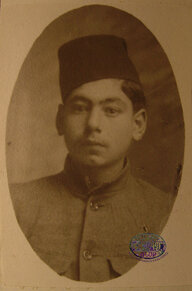

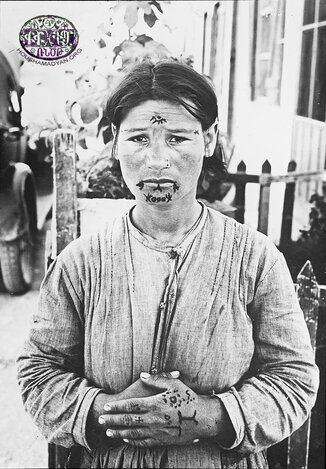

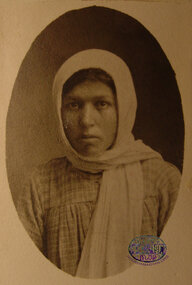

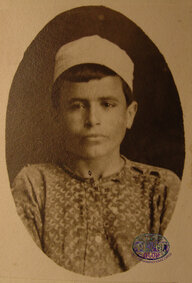

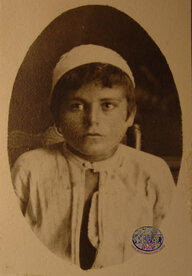

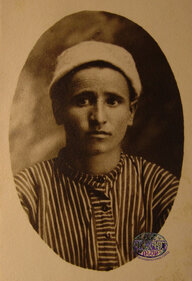

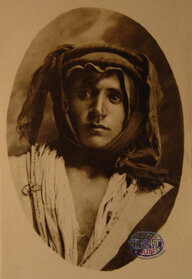

2) Jeghsa Hairobediun [Yeghsa Hairabedian], a twenty-three-year-old tattooed survivor from Adiaman, appeared in several of Karen Jeppe’s personal albums. She lived among Kurds and eventually located her mother nearby. They met in secret, and after 15 years of suffering, they managed to escape and reach Jeppe’s home in Aleppo (Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

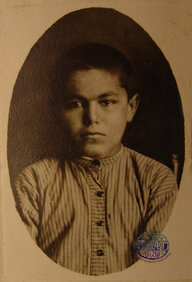

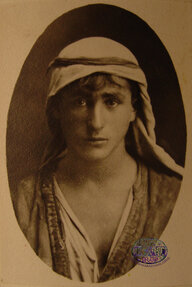

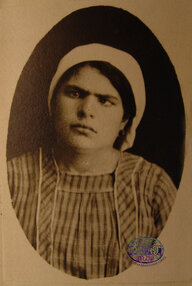

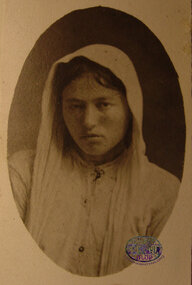

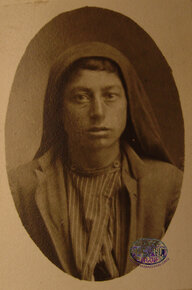

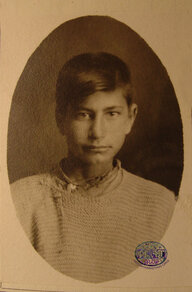

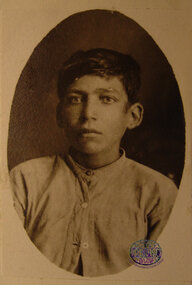

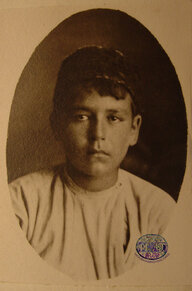

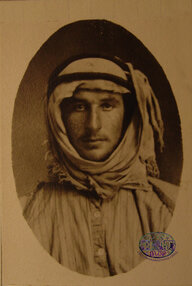

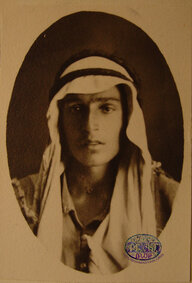

3) Photograph of Dikranouhi [no last name] originally from Bourdour/Burdur, Konya. Her mother gave her to an Arab to spare her “being exposed to the misused of many rude gendarmes” during the deportation, code for sexual abuse suffered by women and girls. The first Arab sold her to another who abused her as a slave for 12 years. In June, 1927, nineteen-year-old Dikranouhi escaped to one of the Armenian colonies Jeppe had established in eastern Syria. Jeppe wrote, “her possessor arrived with many armed men and claimed her yet in our territory she was safe.” One of Jeppe’s agents contacted Hadjim Pasha to mediate the situation since the man who had held Dikranouhi captive for over a decade was his own son! Hadjim Pasha told the agent “put her into a motor-car and send her to your rescue-home in Aleppo. The poor Armenians have suffered much from us, it is enough.” At the Rescue Home, Jeppe was able to find Dikranouhi's mother in Greece; she later joined her in Aleppo. She also overlapped with a young man named Benjamin who was learning to be a tanner who had also been held captive in the east near Mount Sinjar. They married the year after their arrival at the Rescue Home (Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

A dramatized 35 mm documentary silent movie with Danish intertitles about the rescue missions and work at the Rescue Home in Aleppo from 1926. The film’s director is unknown. The movie was commissioned by the League of Nations and made by the production company Pathé France. The movie can be found online in two versions that are 09.50 and 18.35 minutes long, respectively: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O2zfv5x41cQ&t=157s and https://www.europeana.eu/da/item/08601/40639 . The rescue mission depicted in the movie is a composite based on actual rescue missions carried out by Jeppe’s agents in her Ford automobile, and the Armenian escapees Astrig and Lucia depicted in the movie are played by actual Armenian escapees. Furthermore, it is very likely that the Bedouins captors seen in the tent in the movie are played by local Bedouins, as Jeppe and her staff had close personal relations with one or more tribes. In the movie Karen Jeppe embraces rescued women upon their arrival. Several of her employees are featured including Jenny Jensen, Leopold Gaszczyk, his sister Johanna Paritzi, and Jeppe’s adopted son Misak Melkonian. The film depicts how new arrivals were received and registered in the protocols and offers scenes from daily life at the Reception Home, including the school and the workshops (Source: The Danish Film Institute).

After this incident most of the Armenian men went to hide in a basement at a nearby deserted vineyard. But the problems did not disappear for Jeppe. She was constantly harassed by increasingly menacing authorities who were searching for Der Karekin in particular. He was believed to be one of the instigators of the Ourfa uprising; in all likelihood the accusation was false, but that was a moot point, the gendarmes looked incessantly for him. Der Karekin knew that it would end badly, so to save Jeppe and the rest hiding with him and at Jeppe’s house - not least his own children - he had to make the ultimate sacrifice, and his wife wanted to follow him. Thus, to divert the attention of the authorities, the couple drank poison, more precisely strychnine. Then, as the priest had wished, their bodies were carried to a spot by the road where they would be found quickly. Their children cried, the other Armenians did not, they just stood in silence. Bedros der Bedrossian describes the scene this way: “Our own tears had dried out by then.” It was in no way a meaningless gesture, they died, according to eyewitnesses, courageously and dignified, and when the authorities found the bodies it did in fact make life easier for the rest of the fugitives and for Jeppe, at least for a while.

All in all, Jeppe, together with a handful of other Westerners as well as a selected group of Armenian, Arab, and Kurdish helpers managed to hide some 50 Armenians in her house and smuggle most of them to safety disguised as Kurds. Many of those who had fled were wanted by the Ottoman authorities like Der Karekin, so Jeppe hid them well. She did so, first under the floorboards of her house as mentioned above, then in a ditch under a flowerbed in the garden, and finally, after the death of the priest, in a tunnel leading from the basement to the garden. There were regular house searches, and even little Armenian girls under Jeppe’s protection were taken from the house if they were caught. Fear and uncertainty were constant factors in Ourfa.

As Jeppe later wrote: “Back when the Big Death went over Armenia I was there. I experienced it with the unfortunate people; it nearly killed me, that which left its most bloody and indelible mark in my mind, that about which I had the most to tell.” Having experienced the trauma of genocide both personally and professionally, seeing death marches, corpses in the streets, and loved ones being dragged away from her own house, it was the event she had most to tell about. Yet, Jeppe wrote very little about her personal experience. She mostly kept the trauma inside, but still we do know quite a bit about her experiences from various sources - such as herself, Armenian survivors she helped, the Ottoman Arab official Faiz el-Ghusein, the Assyrian priest Joseph Naayem, and Westerners she was in contact with. [7]

Like so many others, including Armenian politicians, Jeppe had been optimistic, even supportive when the Young Turks took power in 1908, but during the siege of Ourfa, she risked the death penalty for saving Armenians. It began in earnest when she, alongside numerous other eyewitnesses, saw columns of Armenians from Harput/Kharpert, Erzerum, Zeitun, Bitlis, and other regions arriving outside Ourfa, the city by the gate to the Syrian desert, during the summer of 1915. She saw thousands of women and children in temporary concentration camps and a slave market that emerged in the city. Armenians were starving, diseased, and dressed in rags and abused by gendarmes and local Turks, Kurds, and Arabs in every conceivable way. Armenian deportees begged for bread and water, and they died in front of her; soon there were corpses everywhere. The Armenian Apostolic cathedral was used as a brothel for mass rapes of Armenian females, and larger structures such as Jeppe’s orphanage were taken over by the Ottoman army and almost all the orphans were killed. Any Armenian survivors were systematically sent to die in the desert.

In Ourfa, the demonization and persecution of the local Armenians had already begun well before the arrivals, and quickly it was clear that they were to meet the same fate as the ones on the death marches. Finally, in August 1915 they did. The Americans and Europeans, including Jeppe, mostly protested and tried to help the deportees and the locals, and so did a few Muslims, as Jeppe notes in a letter to Gertrud Rössler, German consul Walter Rössler’s wife. But most Germans and the vast majority of the locals either stood idle by or actively supported the genocide. On September 29, an epic act of resistance began where Karen Jeppe played her small part. Desperate from waiting for a certain death, the last surviving men, women, and children from Ourfa’s Armenian quarter entrenched themselves behind thick walls and waged guerilla warfare, vastly outnumbered and outgunned, against the regular Ottoman and German troops. After weeks of brutal, heroic fighting the Armenians were defeated. Survivors were hunted down, slaughtered, abused, committed suicide, or were deported to the desert.

Few Armenians were left in the Ourfa region in late 1915, and some two years later, in December 1917, there were literally no more Armenians for anyone to protect. By then, the last ones had left their hiding place in Jeppe’s house by the vineyards in the outskirts of Ourfa, and most others were killed, so there was nothing more for a Danish relief worker to accomplish. Jeppe therefore did what she had been able, but not willing to do all along--she left the Ottoman Empire as a neutral Danish citizen and arrived back in Demark in early 1918. [8]

Karen Jeppe’s Life and Work in Aleppo

From 1918-1921, Karen Jeppe mostly stayed in Denmark working to recover from the post-traumatic stress of witnessing the Armenian genocide at Ourfa and lobbying for the surviving Armenians by giving lectures and interviews. But in early 1921, she and the DA decided that she should go to establish a home for the exiled in the former Ottoman town Aleppo, now part of the French mandate of Syria. A few months after her arrival, she was appointed League of Nations Commissioner for the Protection of Women and Girls in the Near East, which opened whole new avenues of possibilities for relief and developmental work. She had mixed feelings before accepting the appointment, though, as can be seen in a letter she wrote May 1921, shortly after her appointment:

“Really, the Europeans always seem to only deal with Armenian matters in order to fundamentally ruin them one way or the other. But then I thought that this depends to some extent on the people in the Commission [for the Protection of Women and Girls in the Near East]; anyway, it would not make things any better if I stayed out of it.” [9]

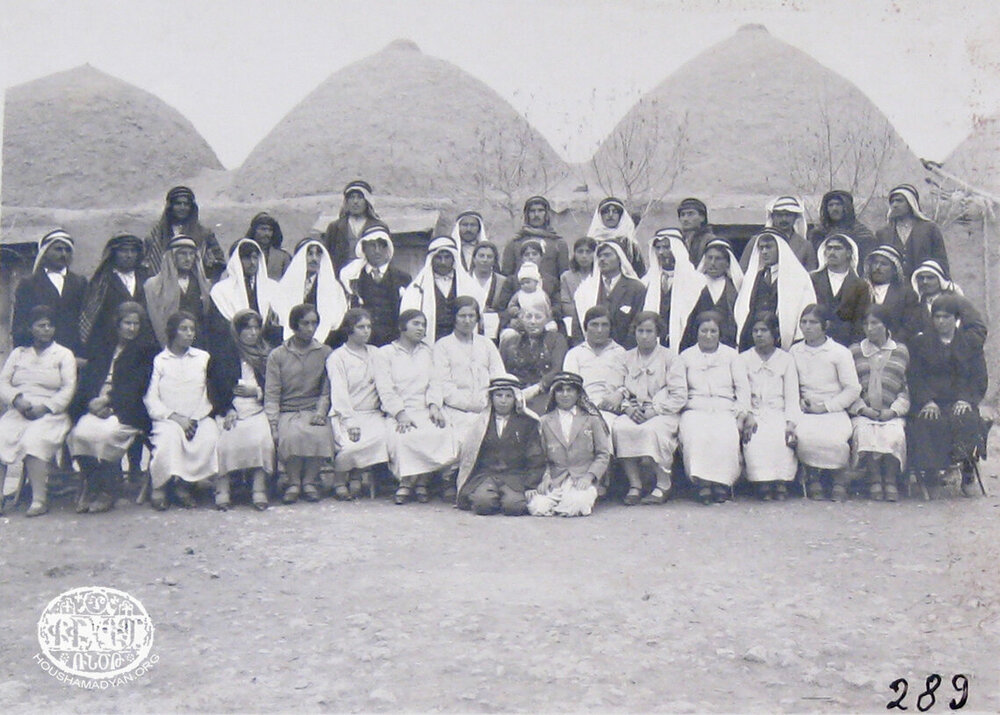

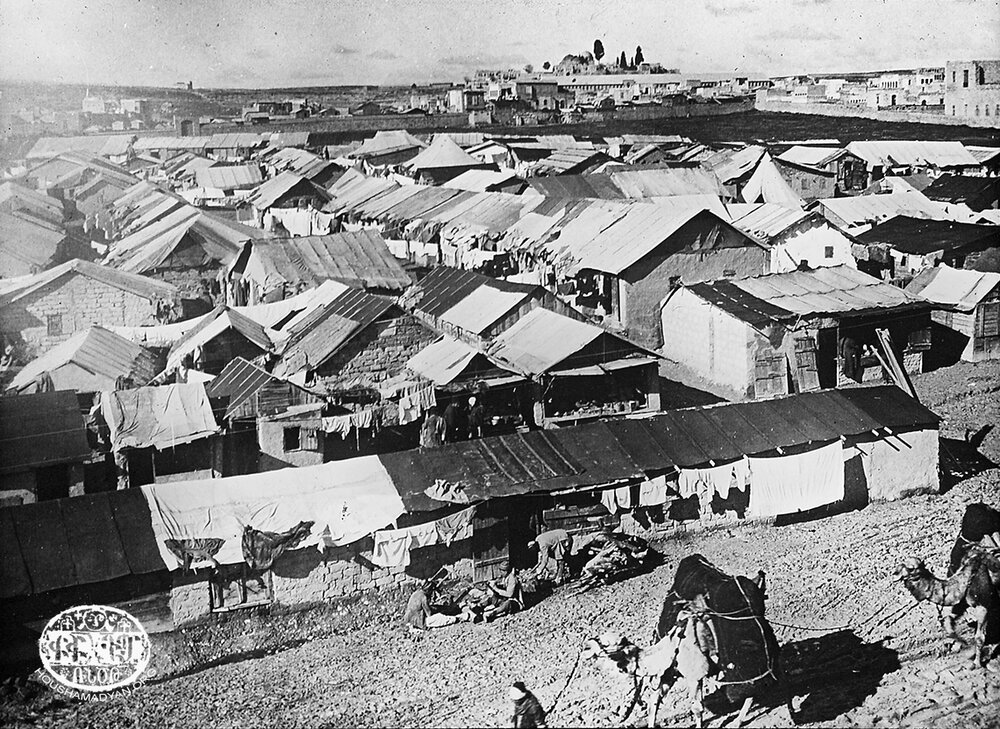

The added support, protection, and funding provided by the League were indeed necessary to supplement the relief work already being conducted by Armenians through the Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople, the Armenian Apostolic Church prelacies in Aleppo and Baghdad, the Armenian Red Cross, the Armenian General Benevolent Union, Dayr al-Zur’s Armenian Catholic Prelacy, Armenian Protestant, and Catholic Churches, that had mobilized during the war to support Armenian refugees throughout the region. [10] There were some 100,000 destitute Armenian survivors in Syria alone, mostly living in primitive refugee camps. Furthermore, 20,000-30,000 of them were women and children who had survived the death marches and were still held in Muslim households, subject to Islamization and very often a life in slavery and abuse.

These forcibly assimilated women and children immediately became the focus of the efforts of Jeppe and her international staff at Aleppo. In 1922, they opened a large Reception Home (a.k.a. Rescue Home) at a compound by the railroad in what would later be called the Shaykh Taha district in the northern outskirts of Aleppo near the Quwayq River, a home where close to 2,000 Armenians would pass through until 1927, helped to escape by a complex network of agents, bribes, persuasion, and negotiation. The word was quickly spread throughout the region that there was an opportunity for Armenians to rejoin their community in Aleppo, which could lead to dramatic flights, and even cost the life of Jeppe’s agent in Hasakah, the Catholic Armenian merchant from Ourfa Vasil Sabagh. The main reason why saving Armenians after the genocide could still be a dangerous business was this: While the project was indeed sanctioned by the League of Nations, there was much local resistance against helping Armenians escape from Muslim households, and the French mandate authorities would also be hesitant to assist Jeppe’s organization in this endeavor to avoid upsetting, e.g., Bedouin tribes. [11]

Stories from the Rescue Home

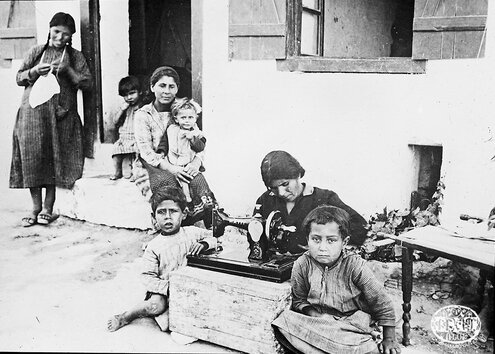

Upon arrival, escapees first got a medical examination and a chance to briefly tell their story which was transcribed into a systematic register in which every “inmate,” as they were called by Jeppe, received a number. The details of their lives were recorded including their names, if they could remember them at all, and the names of their mother, father, and birthplace. An adjacent photography studio snapped portraits of the rescued refugees which was pasted in the upper righthand corner. This identifying information was used in order to track refugees, but also to reunite them with relatives searching for them in Aleppo or as far away as France and the United States. The Rescue Home offered lodging alongside education and vocational training - just as the orphanage in Ourfa before the genocide. There were differences between the new project and the old, of course. Even finding spaces for Armenians to live in Aleppo, due to what Jeppe called a “housing famine,” was nearly impossible. It did not matter if one had the funds to pay for rent.

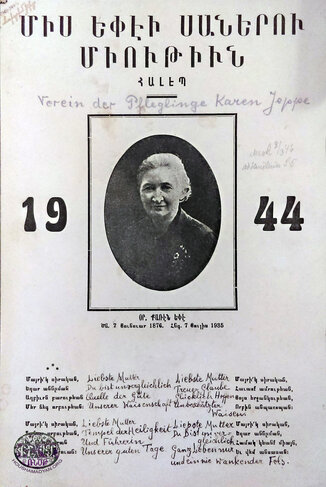

1) A memorial poster with a poem in Jeppe’s honor in German and Armenian made by the Association of Karen Jeppe’s Armenian Orphans in Aleppo. Printed on the ninth anniversary of Jeppe’s death in 1944 (Source: The Danish National Archives, Copenhagen, Demark).

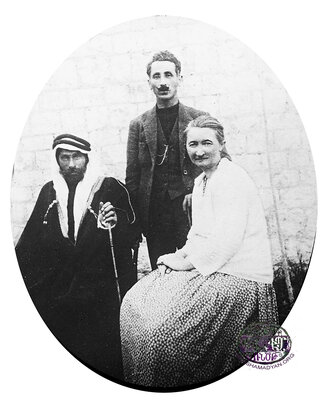

2) From the left: Hadjim [Hashem] Pasha, Misak Melkonian, and Karen Jeppe. Hadjim was a local Arab Bedouin chieftain that Jeppe and her adopted son developed a close personal relationship with. It was also a pragmatic relationship. Hadjim provided land and security for Jeppe’s agricultural colonies – Jeppe never trusted the French colonial authorities in Syria when it came to security and quite a few other matters – while the Armenians at the colonies not only provided grain and vegetables to Hadjim’s tribe and to the region in general, but also, according to Jeppe’s conversations with Hadjim, were a desired factor for development and progress (Source: The Danish National Archives. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

3) A girl in one of the Armenian villages carries a large bundle of wood (Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

In Ourfa, helping orphans was challenging, but in Aleppo, the conditions in the aftermath of genocide were more extreme - every single Armenian they received was deeply traumatized physically and emotionally by the abuse they had endured demanding a higher level of rehabilitation. One survivor, Valantin, was so traumatized upon telling Jeppe her story that she began to shiver, blood ran from her mouth and nose, and she fell to the floor. [12] The rescued sometimes showed up at Jeppe’s doorstep with festering wounds, broken bones, distended bellies, and deformed spines born from multiple beatings. Some wounds were the result of the escape, while others were marks of punishment from cruel household members who never accepted the women and children as their own or punished them when they tried to escape. Women suffered the unique trauma of rape, having been transferred against their will between multiple men as concubines and wives.

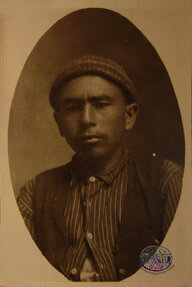

Most of the Armenians who arrived needed urgent medical treatment for gonorrhea, blinding trachoma, and life-threatening dysentery and typhus. Alarming to Jeppe and others was how many rescued Armenians had forgotten their language and culture as the result of mass transfer and assimilation during the genocide. Thus, the Reception Home became “a Babylon of languages,” as genocide survivor Harutiun Tchakerian put it, where Laz, Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab was spoken besides Armenian. [13] Jeppe remarked that "Barkev," a name he was given by relief workers, “does not know anything about his parents, birthplace, or even his Christian name.” [14] Another boy worked hard to remember some Armenian words when he worked as a shepherd by speaking Armenian to his sheep. The stories recorded in the Rescue Home registers provide insights into the state of Armenians rescued by Jeppe as well as the particular ways her program sought to restore them physically, emotionally, religiously, and nationally as Armenians. For women, this meant a specific program to rehabilitate them for remarriage to become the wives and mothers of future Armenians—attested to by documentary evidence of mass marriages in Jeppe’s Armenian colonies.

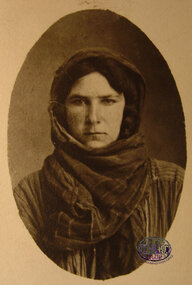

Many of the women and girls who survived had either been forcibly married by their captors, adopted, or absorbed as laborers into Muslim households. While some girls were treated well as adopted children, others endured a decade or more of abuse by jealous wives or male patriarchs. Groomed for marriage to either relatives or fellow tribesmen, the women were absorbed so tightly that, with a few prominent exceptions, Arabs rarely consented to release them. Armenian women and children described the struggle to find an opportunity to escape and the terrible beatings they received when their previous attempts failed. Jeppe observed a woman who had escaped her coerced marriage, “on looking attentively one can see Siranoush’s eyes have been tearless for a long time.” [15] Tattooed between her eyes and on her chin with a traditional Arab tattoo, she was fed very little and worked her hard. She was later married to an Arab as a second wife upon which the first wife began abusing her. Another escaped woman, Mariam, was forcibly married to a Kurd in Viranshehir where she was made, illegally, his fifth wife. Jeppe described the woman’s situation poetically, “she made untold efforts to make her way out of the dark abyss of misery in which she had to disappear at the peril of her life. But Meriam in spite of all dangers had resolved earnestly to flee and she made all possible efforts to rescue herself of that hell.” Mariam did indeed rescue herself from her captivity, eventually reaching Mardin where she reached one of several agents working for Jeppe. [16]

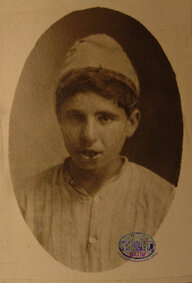

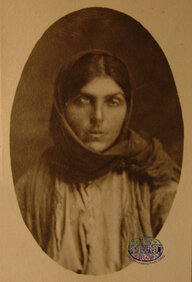

(Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

In other cases, upon learning of the rescue mission, Muslim Arabs of the Jazira region of Eastern Syria willingly released the Armenians of their households. Al-‘Asima, the Damascus newspaper belonging to Syria’s new ruler King Faysal, articulated his demand to his subjects that those holding Armenians must release them to the authorities to comply with the League efforts to reclaim dispersed Armenians. [17] Some Muslims told the Armenians living in their homes that there were no Armenians left in the world. While this could be viewed as deceptive misinformation, as first-hand witnesses to the carnage in the Syrian Desert, some Arabs may have sincerely believed this to be true— an estimated half million Armenians had perished in the region. [18] Terrified for her safety and uncertain that the news about the Rescue Home was true, one Arab hand-delivered the young woman living in his household to Jeppe. In addition, some Armenian women faced the difficult choice of leaving their children born with Muslim husbands; some left their children behind; others took their half Muslim children with them to Aleppo.

Importantly, the Rescue Home offered an opportunity for separated Armenians to reunite with family members. A twelve-year-old boy named Onnig—a name given to him by the reception home because he did not remember his original Armenian name—remembered nothing about his family. He had always been with Arabs as long as he remembered and “he thought that he himself was an Arab.” [19] He was described as “a firm little fellow” who liked to roll and smoke his own cigarettes, something forbidden in the home. Assimilated among the Bedouin, Onnig threatened to run away if the rescue home workers cut his long hair and took away his Arab headdress. One day, while walking down the street his mother found him and cried out to him. He could not understand her since he had lost his Armenian long ago, having lost his mother in Raqqa at six months of age. Through an identification process developed by Jeppe, Onnig and his mother were reunited. The mother and son sat for a portrait afterward, and interestingly, he was still wearing theheaddress.

Through the meticulous care offered at the home, most women and children like Onnig became ready to move on in life. And when they did, Jeppe kept helping individual women and children find missing relatives, homes, and jobs in Syria or abroad. Her organization also, among other things, sponsored children at Armenian Apostolic educational institutions such as the Saint Mesrop and Sahagian schools in Aleppo, ran soup kitchens and clinics, and even cooperated with local French and Arab authorities to establish whole agricultural villages (also called “colonies”) for Armenians east of the Euphrates. Thereby she was realizing a project of Armenian settlement and employment she had already begun outside Ourfa during the last years before the genocide. Furthermore, to find even more large-scale solutions, Jeppe worked with, e.g., Norwegian humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen to secure migration of Armenian exiles in larger groups to places like South America, Australia, Greece, and the Soviet Armenian Republic. Ideally, she wanted proper homelands for the survivors where they could live together and preserve their culture, etc., preferably with some measure of self-rule. This never really materialized, though, making it Jeppe’s only major disappointment during the Aleppo years.

The Later Years

The world war and the genocide were over, but new refugees kept coming—victims of the continuing repression of minorities in the new Turkey. Most of them were Kurds, and with them came more Armenians, who had been rescued and/or abducted by them from 1915. During the 1920s and early 1930s there was never a shortage of tasks for Jeppe and her staff, not even after she stopped working for the League of Nations and once more worked merely for DA. There was still turmoil in the Middle East, including in Syria, with occasional uprisings. It became more difficult to establish new colonies up north, or even keep the existing ones, as the French mandate authorities tended to cave in to demands by Turkish authorities when they objected to any substantial concentrations of Armenian or Kurds by the new Turkish-Syrian border. And, though Jeppe received a gold medal from the Danish king for her efforts in 1927, it became an increasing struggle to make the public eye focus on the Armenian plight. Luckily, Jeppe still had her broad Danish support and her vast international network, not least in Germany. As she wrote in a letter back home July 1931:

“When I was a little girl being educated by my father I remember that he taught us about the sun, starting like this: “If we really want to realize what the sun means to us, let us then begin by imagining that it did not exist.” And then he vividly painted a gruesome picture in our minds. Indeed, what would happen to the more than 300 fatherless children if the German contribution to us was halted? Let us hope it does not happen!” [20]

(Source: The Karen Jeppe Archives, Gylling, Denmark. Courtesy of Mihran Minassian).

Because Armenians were still “a people without a country,” as the saying went, and the trauma and material difficulties the survivors had to deal with did not just go away. Jeppe worked constantly, only allowing herself a bit of rest every now and then at the little white house she and her staff used for recreation in Tel Armen, one of the Armenian villages she established. Once or twice, when the recurring symptoms of malaria become too severe, she would travel to her favorite Swiss mountain retreat near Geneva, the only luxury she ever allowed herself.

Karen Jeppe’s Death and Legacy

It was at Tel Armen, the Armenians’ Hill, in 1935 that Karen Jeppe was seized by her final fit of malaria, when her “enfeebled body” was quickly overcome with a high fever that would not drop. She was rushed to a French hospital in Aleppo by car (the indestructible Ford automobile once donated by Anna Gilpin, an American beneficiary), but though she received the best treatment available, she died there seven days later, 59 years old and surrounded by grieving Armenian, Danish, Norwegian, and French colleagues, friends, and family. [21] At last, her frail body was worn out for good. Jeppe could not lie in independent Armenian soil, as had been her first choice, but she got the next best thing: An Armenian funeral at an Armenian Apostolic church and a burial at the Armenian Orthodox cemetery in the Shaykh Maqsud district of Aleppo. The memorial poem written by the Association of Karen Jeppe’s Orphans in Aleppo in 1944 affirms the special place she holds in the hearts of the Armenians she rescued: “Beloved mother, temple of holiness, our leader into the good days.”

The Danish humanitarian has long been a name remembered by the Armenians of Aleppo and beyond. On October 15, 1947, in order to honor her, Archbishop Zareh of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Aleppo opened the Karen Jeppe College in the compound in Maydan where many of her operations took place during her life and long after her death, including the so-called “Widow Village.” [22] The Maydan (Armenian: Nor Gyugh or “New Village”) district of Aleppo, where she moved most operations to in 1928, was once a refugee camp and later became an emerging hub for Armenian settlement after World War I, until most of the neighborhood was destroyed during heavy fighting in the recent Syrian war. Jeppe is also remembered on, for instance, on a stamp in Armenia; in the Karen-Jeppe-Strasse, the name of a street in Potsdam, Germany; in the name of a group of scouts in Denmark; in her small, quiet town of birth, Gylling, where there is a small archive and a memorial stone in her honor, and on a khachkar, an Armenian cross stone in memory of the victims of the Armenian genocide; and in the hearts and minds of descendants of survivors everywhere in the diaspora and humanitarians who remember her by the epithets of “Protestant saint,” “a pioneer women peacemaker,” “a liberation philosopher,” and “a Danish Florence Nightingale.” [23]

She is indeed hard to forget, Karen Jeppe, this intense, quiet, pragmatic idealist with a dry sense of humor, a weak health, and a strong constitution; a paradox, perhaps. With open eyes she gave up her beloved family, country, and a personal love life for the love of the Armenian people. Kevork Garebedian, who as a child hid under her floor boards in Ourfa in 1915, wrote of Jeppe upon her death: “The Armenians must give her a resting place in the Armenian pantheon where their heroes abide in Erivan [Yerevan], as a token of their ever-lasting honour, she has so worthily deserved and their indebtedness so great to repay, so that future generations may come to know what a Danish Lady—an immortal heroine--has done for their forefathers in days of their distress out of the generosity of her heart and vicariously.” [24]

- [1] Keith Watenpaugh, Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, Berkeley: University of California Press 2015, pp. xi-xiii.

- [2] Karen Jeppe, “Account of the situation of the Armenians in Syria,” Baalbek, August 24, 1922, De Danske Armeniervenner (DDA), Box 10, Folder A, Danish State Archive, 7-8.

- [3] Karen Jeppe, Missak: An Armenian Life, trans. ed. intro. Jonas Kauffeldt, London: Gomidas 2015, p. xii.

- [4] Matthias Bjørnlund, “Karen Jeppe, Aage Meyer Benedictsen, and the Ottoman Armenians: National Survival in Imperial and Colonial Settings,” Haigazian Armenological Review, vol. 28, 2008, pp. 9-43.

- [5] See Ingeborg Maria Sick’s obituary for Jeppe in “Karen Jeppe of Denmark and Armenia,” The American-Scandinavian Review, p. 19.

- [6] Matthias Bjørnlund, På herrens mark. Nødhjælp, mission og kvindekamp under det armenske folkedrab, Kristeligt Dagblads Forlag 2015, pp. 93ff.

- [7] The most important sources to the death of Der Karekin and his wife, as well as to Jeppe’s experiences during the genocide in general, are the unpublished eyewitness accounts by Bedros der Bedrossian and Kevork Garabedian, Danish National Archives, Archives of the Danish Friends of Armenians, 10158, “1919-1949,” “Diverse materialer,” pakke 10; The Karen Jeppe Archives at Gylling; Bedros Der Bedrossian, Autobiography and Recollections, Philadelphia: AIWA Press 2005; Karen Jeppe, Misak. Et Livsbillede fra Armenien, serialized recollections in Armeniervennen, 1922-1929; Ephraim K. Jernazian, Judgment unto Truth:Witnessing the Armenian Genocide, New Brunswick & London: Transaction Publishers 1990. More generally on the genocide in Ourfa, there is rather much literature these days, e.g., Jakob Künzler, In the Land of Blood and Tears: Experiences in Mesopotamia during the World War (1914-1918), Arlington, MA: Armenian Cultural Foundation 2007 (1921); Hans-Lukas Kieser, Der verpasste Friede. Mission, Ethnie und Staat in der Ostprovinser der Türkei 1839-1938, Zürich: Chronos-Verlag 2000; Hilmar Kaiser, ed., Eberhard Count Wolffskeel von Reichenberg, Zeitoun, Mousa Dagh, Ourfa: Letters on the Armenian Genocide, Primceton, NJ: Gomidas Institute 2001.

- [8] The above account is mostly a distilled, reworked version of chapter 7 in Bjørnlund, 2015.

- [9] Letter from Jeppe published in Armeniervennen, Gylling Archives. We thank Mogens Højmark for providing it.

- [10] On Armenian humanitarian resistance, that is the broad efforts of Armenians to save Armenians while the genocide was underway, see Hilmar Kaiser, At the Crossroads of Der Zor: Death, Survival, and Humanitarian Resistance in Aleppo, 1915-1917, London: Gomidas 2002; and Khatchig Mouradian, The Resistance Network: The Armenian Genocide and Humanitarianism in Ottoman Syria, Lansing: Michigan State University Press 2020.

- [11] Bjørnlund, 2015, pp. 210-217; www.armenocide.de; Jernazian, 1990, passim; Hermann Goltz & Axel Meissner, Deutschland, Armenien und der Türkei 1895-1925, Dokumente und Zeitschriften aus dem Dr. Johannes-Lepsius-Archiv an der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Teil 3, Thematisches Lexicon zu Personen, Institutionen, Orten, Ereignissen, München: K. G. Sauer 2004, p. 435.

- [12] “Valantin,” Inmate Registers, Archive of the League of Nations (ALON), 1091.

- [13] Harutiun Tchakerian (Tschakerian), “Zum 10-jährigen Todestags unserer geliebten Mutter Karen Jeppe 7.7. 1935 - 7.7. 1945,” Danish National Archives (Rigsarkivet), DA 10158, “1919-1949,” “Diverse materiale,” pakke 10, Aleppo 1945.

- [14] “Barkev” Inmate Registers, ALON, 710.

- [15] “Siranoush” Inmate Registers, ALON, 1029.

- [16] “Mariam,” Inmate Registers, ALON, 1079.

- [17] Declarations to release Armenians were published in Arabic in King Faysal’s newspaper in Damascus, Al-‘Asima, May 19, 1919. The newly-formed government also supported the efforts of local Armenians to collect orphans, girls, and women. Nora Arissian, Asda’ al-abadat al-armaniyya fi al-sahafa al-suriyya (1930-1877), Beirut: Dar al-thaikra 2004, pp. 112-113; Levon Yotnakhparian, Crows of the Desert: The Memoirs of Levon Yotnakhparian, trans. Victoria Parian, Tujunga, CA: Parian Photographic Design 2012.

- [18] On this “second phase” of the genocide, see in particular Raymond Kévorkian, The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History, New York: I. B. Tauris 2011, passim.

- [19] “Onnig” Inmate Registers, 1325, LON. This story is also retold in more detail by Jenny Jensen, “Fra Optagelseshjemmet,” Armeniervennen, July-August 1929, pp. 29-30.

- [20] Gylling Archives. We thank Mogens Højmark for the reference.

- [21] Ingeborg Marie Sick, “Karen Jeppe of Denmark,” p. 25.

- [22] The former Karen Jeppe College (jamaran) in Nor Gyugh/Maydan is not a university but something more akin to secondary school in the European and American schooling system. Information about the college and the place of Jeppe’s internment in Aleppo can be found in Hagop Cholakian, "Karen Yeppe: Hay koghkotayin yev veradznountin hed", Aleppo: Arevelk, 2001, pp. 158-159.

- [23] Ernest Barron Gordon, A Book of Protestant Saints, Chicago: Moody Press 1946; Matthias Bjørnlund, “Da Danmarks Florence Nightingale fandt sit kald i livet,” Kristeligt Dagblad, 26 December 2015; Elisabeth Lyneborg, Karen Jeppe, København: Lindhardt & Ringhof 2020; Eva Lous, “Karen Jeppe - Danmarks første befrielsesfilosof,” Det Danske Fredasakademi 2003, .http://www.fredsakademiet.dk/library/jeppe.htm .

- [24] Kevork Garabedian,“Miss Koren Yeppe: Mother” Baghdad, Iraq, n.d. De Danske Armeniervenner (DDA), Box 10, Folder A, Danish State Archive, 2.

Archives

- Danish National Archives (Rigsarkivet), Copenhagen, Denmark

- Danish National Library (Det Kongelige Bibliotek), Copenhagen, Denmark

- Lokalhistorisk Arkiv for Gylling og Omegn, Karen Jeppe-samlingen, Gylling, Denmark

- Archive of the League of Nations, Geneva, Switzerland

Selected Readings

- Dicle Akar, Matthias Bjørnlund, Taner Akçam, Soykırımdan kurtulanlar: Halep kurtarma Evi Yetimleri,İstanbul: Iletişim Yayınları 2019.

- Nora Arissian, Asda’ al-abadat al-armaniyya fi al-sahafa al-suriyya (1930-1877, Beirut: Dar al-thaikra 2004.

- Matthias Bjørnlund, På herrens mark. Nødhjælp, mission og kvindekamp under det armenske folkedrab, Kristeligt Dagblads Forlag 2015.

- Hagop Cholakian, "Karen Yeppe: Hay koghkotayin yev veradznountin hed", Aleppo: Arevelk, 2001.

- Lerna Ekmekcioglu, Recovering Armenia: The Limits of Belonging in Post-Genocide Turkey, Stanford: Stanford UniversityPress 2016.

- Edita Gzoyan, “Women Survivors of the Armenian Genocide: Liberation and Relief at the Aleppo Rescue Home,” Central & Eastern European Review, vol. 13, 2019, pp. 13-30.

- Aschot Hayruni, Im Einsatz für das bedrohte Volk der Armenier - Johannes Lepsius und seine Mission, (Eastern Church Identities), Paderborn: Verlag Ferdinand Schöning 2020.

- Karen Jeppe, Missak: An Armenian Life, trans. ed. intro. Jonas Kauffeldt, London: Gomidas 2015.

- Rebecca Jinks, “Marks Hard to Erase: The Troubled Reclamation of “Absorbed” Armenian Women, 1919-1927,” The American Historical Review, vol. 123, no. 1, February 2018, pp. 86–123.

- Jonas Kauffeldt, Danes, Orientalism, and the Modern Middle East: Perspectives from the Nordic Periphery, Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University 2006.

- Dzovinar Kévonian, Réfugiés et diplomatie humanitaire: les acteurs européens et la scène proche-orientale pendant l'entre-deux-guerres, Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne 2004.

- Helle Schøler Kjær, 1915 - Danske vidner til det armenske folkemord, Copenhagen: Vandkunsten 2009.

- Nicola Migliorino, (Re)constructing Armenia in Lebanon and Syria: Ethno-cultural Diversity and the State in the Aftermath of a Refugee Crisis, New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books 2008.

- Khatchig Mouradian, “Genocide and Humanitarian Resistance in Ottoman Syria, 1915-1916,” Études arméniennes contemporaines, vol. 7, 2016, pp. 87-103.

- Khatchig Mouradian, The Resistance Network: The Armenian Genocide and Humanitarianism in Ottoman Syria,Lansing: Michigan State University Press 2020.

- Vahram L. Shemassian, “The League of Nation and the Reclamation of Armenian Genocide Survivors,” in Richard G. Hovannisian, ed., Looking Backward, Moving Forward: Confronting the Armenian Genocide, Routledge: London & New York 2017 (Transaction Publishers 2003), pp. 81-112.

- Ingeborg Maria Sick & Pauline Klaiber, Karen Jeppe im kampf um ein Volk in not, Stuttgart: Steinkopf 1929.

- Ingeborg Maria Sick, “Karen Jeppe of Denmark and Armenia,” The American-Scandinavian Review, vol. 25, no. 1, 1938, pp. 18-25.

- Niels Arne Sørensen, “Humanitarianism (Denmark),” 19 November 2018, encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/humanitarianism_denmark .

- Vahé Tachjian, “Mixed Marriage, Prostitution, Survival: Reintegrating Armenian Women into Post-Ottoman Cities,” in Nazan Maksudyan, ed., Women and the City, Women in the City. A Gendered Perspective on Ottoman Urban History, New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books 2014, pp. 86-106.

- Keith D. Watenpaugh, “The League of Nations' Rescue of Armenian Genocide Survivors and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, 1920–1927, American Historical Review, vol. 15, no. 5, December 2010, pp. 1315-1339.

- Keith D. Watenpaugh, Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, Berkeley: University of California Press 2015.

- Levon Yotnakhparian, Crows of the Desert: The Memoirs of Levon Yotnakhparian, trans. Victoria Parian, Tujunga, CA: Parian Photographic Design 2012.