Diyarbekir – Schools

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 05/11/20 (Last modified 05/11/20) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Armenian population of the city of Diyarbekir and the surrounding area on the eve of the Armenian Genocide.

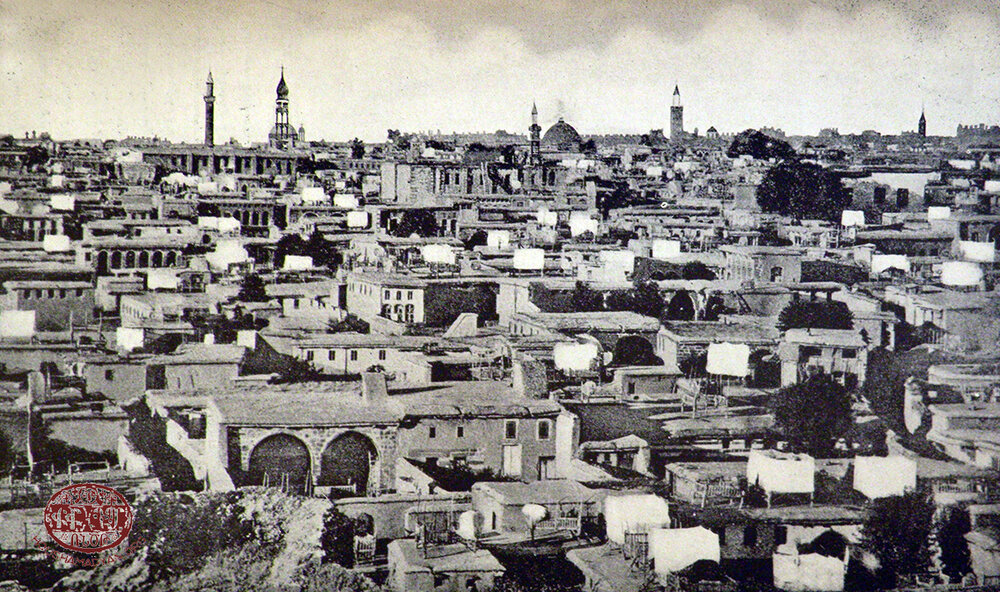

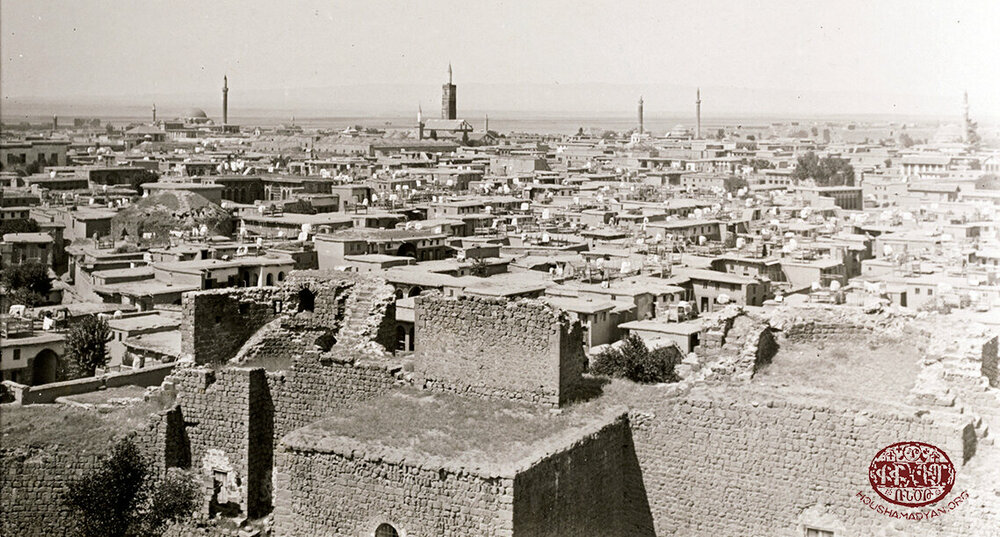

The city of Diyarbekir (historical Amid, Amed) was one of the large population centers located on the border between the province of Aghtsnik of Greater Armenia and the region of Armenian Mesopotamia, in the southwest corner of historical Armenia [1].

The Armenian authors of the Middle Age associated the city of Diyarbekir with the city of Dikranagerd, founded by King Dikran (Tigranes) the Great of Armenia [2]. The Armenian residents of the city also called their home Dikranagerd [3].

Ottoman rule was established over Diyarbekir in 1515. The city became the capital, or provincial seat, of the eponymous province (eyalet, later vilayet) [4].

In the 1870s, approximately half of the population of the city of Diyarbekir was Christian, about three-fourths of whom were Armenian. In later years, especially after the 1895 Hamidian massacres, there was a decline in the percentage of Armenians as a proportion of the general population, leading to a similar decline of the proportion of the city’s Christian population [5].

According to the figures of the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate from 1913, the sub-district of Diyarbekir was home to 3,271 Armenian households and 16,352 Armenians. A total of 14,100 Armenians, or 2,935 households, lived in the city of Diyarbekir. 2,252 Armenians, or 336 households, lived in 47 villages across the sub-district with an Armenian presence [6]. Aside from Armenians, the sub-district was home to an additional 5,801 Christians (the great majority of them Syriacs). The total Muslim population of the sub-district was 51,908 (the majority of them Kurdish), and the number of adherents of other religions was 521 (mostly Jewish) [7].

The Armenian villages of the sub-district were divided into two clusters separated by the Tigris River – the western cluster (Gharb Nahie) and eastern cluster (Shark Nahie) [8]. Gharb Nahie consisted of 24 Armenian-populated villages. Aside from Ali Pounar (Alipounar) and Hayeghigits (Hay Yeghig), the Armenian population of the other villages was not permanent. These Armenians were marabas, or field hands/farmers who lived in rented accommodations. Often, they would relocate to other areas in pursuit of better opportunities [9]. As for Shark Nahie, it included approximately ten villages with a permanent Armenian population (Kuturbul, Irindjil, Kabasakal, Karabash, Satoukegh, Arzoghli, Baghchenig, Djrnig, etc.) [10].

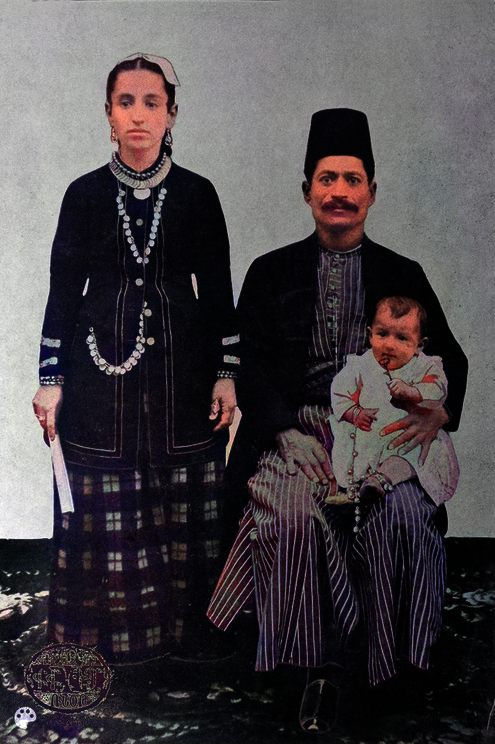

Like in other cities of Western Armenia, the main occupations of the Armenians of Diyarbekir were commerce and the crafts. The preferred fields of Armenian craftsmen were jewelry, weaving, and sericulture [11].

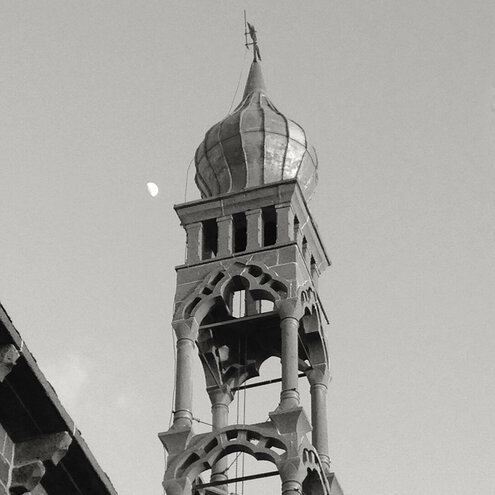

Diyarbekir was the seat of the Dikranagerd Diocese of the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate [12]. In the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, there were two functioning Armenian Apostolic churches in the city, Saint Giragos (with its seven altars) and Saint Sarkis (with its five altars) [13]. The Armenian neighborhoods of the city were concentrated around these two churches [14].

The schools of Diyarbekir between 1850 and the 1870s. The work of Archbishop Pilibbos.

“To raise the next generation of selfless individuals through education and edification”

The foundations of the modern Western Armenian educational system were laid with the special edict issued by Garabed III Balatsi, Patriarch of Constantinople, on 10 July 1824. The edict ordered the prelates of all dioceses under the jurisdiction of the patriarchate to establish schools “for the edification of the children of the church” [15]. This decree spurred the proliferation of parochial schools functioning alongside local churches throughout the cities and provinces of Western Armenia, including the city of Diyarbekir.

The next momentous event in the history of Western Armenian education came in the form of the Armenian National Constitution, adopted in 1860 [16]. The Constitution created the system that coordinated the Armenian “national”-community (parochial) schools across the Empire – a system that operated without any fundamental modifications until the Armenian Genocide. An educational council was formed alongside the Armenian Patriarchate, known as the Constantinople Central Educational Council. This group was tasked with supervising the Armenian educational system across the Empire. The council’s specific aims were to oversee the “reforms” of “national”-community schools; to support the educational/”cultural” [17] organizations that had been established to support the work of Armenian schools; to contribute to the preparation of “proficient” teachers (this included the awarding of the council’s own certificates of endorsement to worthy teachers); to publish textbooks; etc. The council also helped formulate a standardized educational program for “national”-community schools, created templates for graduation diplomas, and attended to other similar duties (see National Constitutions of Armenians, Article 45) [18].

The direct, immediate supervision of “national”-community schools and the provision of necessary supplies to ensure their proper operation was the duty of each respective area’s neighborhood council, or each school’s board of trustees appointed by the respective neighborhood council (Article 52). All necessary funds for the operation of these schools were to come from the respective neighborhood councils’ “coffers” (budgets). These funds consisted of the locals’ neighborhood taxes, income generated from the estates of the church or the school, income generated from the church, bequests, gifts and donations, etc. (Article 53). Each neighborhood council was required to maintain direct contact with the Constantinople Central Educational Council and discuss all issues related to the operation of the local schools (Article 54) [19].

The Central Educational Council soon issued a standardized educational program for Armenian “national” schools across the Ottoman Empire. This was mostly a copy of European programs, namely the French educational program. The tiers of pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, grammar school, elementary school, and secondary school were established. For each tier, the program specified the subjects to be taught, the number of classes, the length of each class, and recommended rewards and punishments for pupils. The program also specified the separation of grade levels, the different tiers of schooling, a standardized class schedule, detailed instructions on holding lessons, a recess schedule, a list of holidays, etc. Some time later, “national” Armenian schools also adopted the system of evaluating students’ work with grades, of final examinations, and of the distribution of graduation diplomas [20].

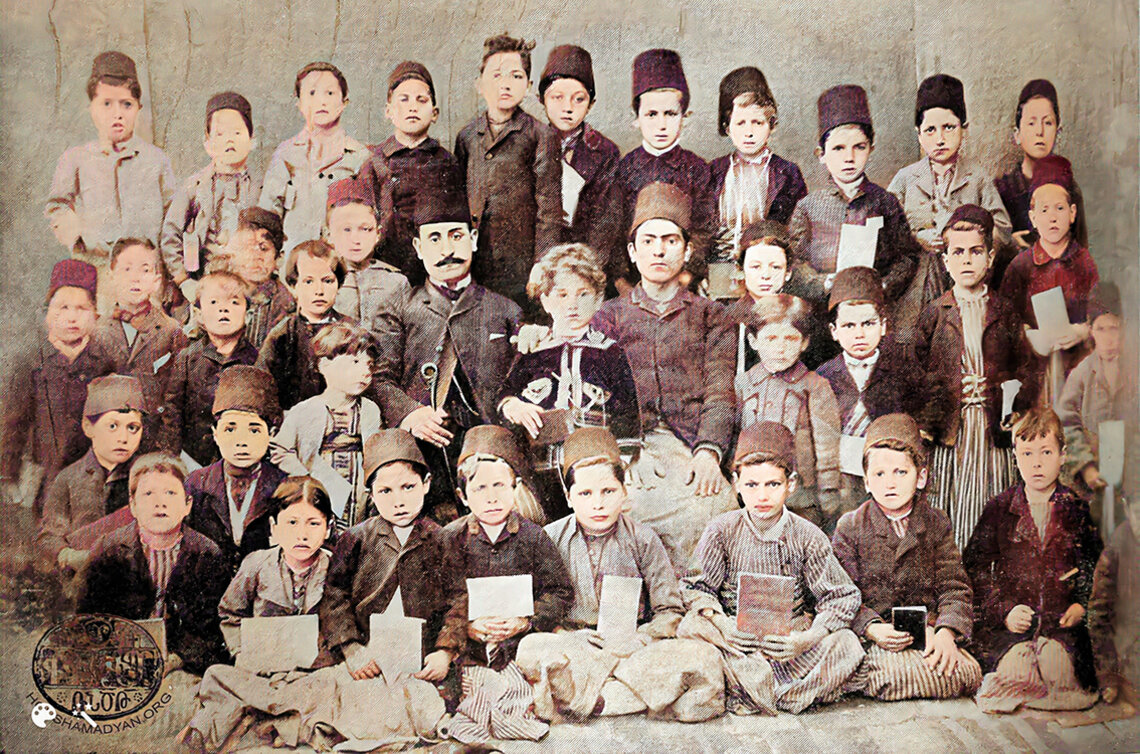

The first references to Armenian “national”-community schools operating in Diyarbekir appear to be from the 1850s. Thus, sources indicate that in 1857, girls’ schools operated alongside the city’s Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis churches (the sources call these schools varjadouns [“schoolhouses”]). A total of 70 girls were enrolled in the Saint Giragos School, and 50 in the Saint Sarkis School. The number of students showed signs of growing, as “the desire for education was spreading among the people” [21].

In addition to these two schools, in the same year, a boys’ school was opened in the city, with an enrollment of 200 pupils (our sources don’t indicate which church this school was affiliated with; presumably, it was affiliated with the Saint Giragos Church). This was a grammar school that mostly taught reading and writing, as well as church singing. It was funded by the Sourp Lousavorich [Holy Illuminator] educational-“cultural” society, which consisted of a group of wealthy Armenians. According to one source, “Apostolic boys who hitherto attended schools of other faiths flocked to this school” [22].

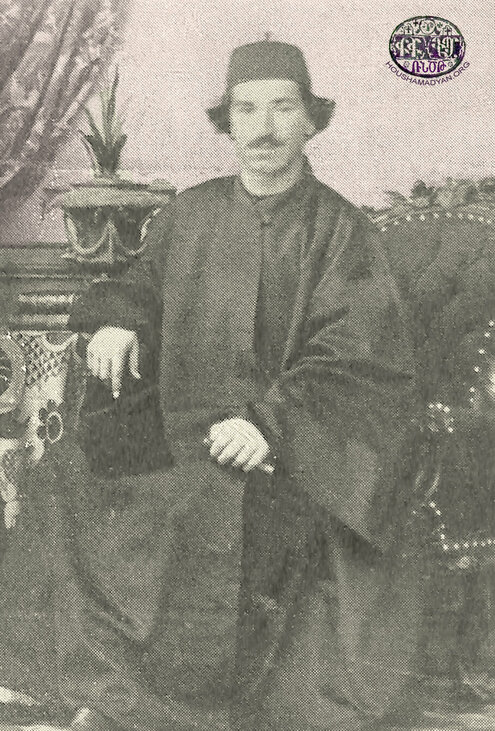

The progress in the field of Armenian education in Diyarbekir between 1850 and the 1870s owed much to the efforts of Mgrdich Ekmekdjian (1775-1885). Ekmekdjian was a well-known intellectual, “schoolmaster,” and teacher/supervisor who worked at the Saint Giragos School and the city’s other schools. His efforts resulted in the founding of the Diyarbekir chapter of the Antsnver [Altruistic] educational-“cultural” society, an organization headquartered in Constantinople. One of the main initiatives of this organization was the organizing of Sunday school classes for local Armenian craftsmen, with the goal of teaching them how to read and write Armenian. According to one account, “In the 1870s, the main school building of the Saint Giragos Church was a lively place on Sundays, when it hosted the Arhesdavorats [Craftsmen’s] School, led by Teacher Mgrdich” [23]. Among the subjects taught by Teacher Mgrdich at the Sunday school and the Saint Giragos School were Armenian grammar, interpretations of the Nareg and of church hymns, mathematics, geography, the Holy Books and Armenian history, logic, and rhetoric [24].

Between the 1860s and 1880s, one of the most prominent figures in the field of education in Diyarbekir was Tovmas Zavzavatdjian. In 1865, with the help of other “devotees of education,” he founded the Hayrenaser [Patriotic] Society. In that same year, this organization opened the Hayrenasirats coeducational school, which would play an important role in the life of the community (see the appropriate section of this article for additional details) [25].

Another initiative by Zavzavatdjian was a series of lectures and discussions for adults, held on Sundays. With these events, he attempted to inculcate in his listeners a desire to “advance in their crafts;” and to encourage the poor to “learn skills that allow them to earn a living, instead of begging or relying on the church” [26].

Zavzavatdjian’s lectures, and the general pattern of his educational/instructional undertakings, effectively brought him into conflict with the church’s charitable work for the poor. This invited the displeasure of the diocese prelate, Archbishop Hagop Papazian. In this clash between the archbishop and Zavzavatdjian, the former had the support of the local commercial circles, and the latter of the esnaf (craftsmen/artisan) class. As tensions rose, in a sermon delivered from the pulpit, the archbishop dubbed Zavzavatdjian “faithless and Godless,” then ordered priests to make the rounds of the city and exhort the people not to send their children to the Hayrenasirats School. Zavzavatdjian responded with a play performed by the pupils of the school, entitled Ignorance and Progress. In the play, the character of “progress” chased away the character of “ignorance” from the Armenian nation.

Zavzavatdjian soon presented a second play, entitled Norayr, which underlined the importance of a good education, based on solid moral values, from a young age. The play ended with the following symbolic lines: “To love and help each other, this is the essence of the Bible, the death of science, and the goal of civilization. Those who help will be helped, those who raise will rise. Blessed are those who have ears to hear this message!” [27].

The plays, and the impression they left on the locals, did not please Archbishop Hagop Papazian, who resorted to denouncing his rival to the authorities. In early April 1872, Turkish policemen appeared at the Hayrenasirats School and ordered its closure, informing Zavzavatdjian that “the governor pasha has heard that agitators were being bred in this school” [28]. After the closing of his school, Zavzavatdjian temporarily retired from teaching.

The events surrounding the Hayrenasirats School were widely discussed in Western Armenian media and intellectual circles. In the summer of 1874, Archbishop Nerses Varjabedian, the newly elected Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, removed Archbishop Hagop from the position of prelate, and appointed the young cleric Father Pilibbos Nadjariants (Khoundjariants) (styled archbishop in the summer of 1876) as interim prelate [29].

Upon his arrival in Diyarbekir, some of the Archbishop Pilibbos’ first initiatives were the re-opening of the Hayrenasirats School; the construction of a new, “well-lighted and magnificent” building for the Saint Giragos School (in the courtyard of the eponymous church); and the opening of a new girls’ school (with Anna Hagopian serving as teacher) [30].

The newly appointed prelate made it a priority to ensure the growth of community organizations that played an important role in the Armenian educational system of Diyarbekir – the Antsnver, Hayrenaser, and Mesrobian “cultural” societies. These groups were led by committees whose members represented the proud esnaf class and “did not shrink from any sacrifice” [31]. Aside from the regular, internal meetings that these leadership committees convened, they also came together for monthly “joint” sessions presided by Archbishop Pilibbos. During these meetings, the prelate would make use of his “fatherly, mild, and persuasive” tone to reconcile and coordinate the work of these disparate organizations, allowing them to complement each other’s work. The archbishop always emphasized the importance of education and schooling, “often repeating the words of Zahari Stoyanov, the Bulgarian exile [32]: ‘To raise the next generation of selfless individuals through education and edification’” [33].

According to a contemporary account, “Archbishop Pilibbos had captured the hearts of the common people. Three societies were formed by the locals, [a reference to the previously mentioned Hayrenaser, Antsnver, and Mesrobian societies – ed.] and their members created “committees” that were in awe of Archbishop Pilibbos and, encouraged by him, engaged in efforts to improve the local educational system” [34].

An extensive report published on 13 April 1879, entitled Vidjag Azk.[ayin] Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi [Report on the National Schools and Societies of Dikranagerd], sheds light on the successes of the diocese’s interim prelate in the field of education. According to the report, the schools operating in the city were the boys’ and girls’ schools of the Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis churches, alongside their respective kindergartens; as well as the schools of the Antsnver, Hayrenaser, and Mesrobian societies. In total, Dikranagerd was home to seven “national”-community and private Armenian educational institutions, with a combined enrollment of 443 pupils [35] (for detailed numbers on each of the schools, see the appropriate section of this article).

In the educational and other community-”national” spheres, Archbishop Pilibbos gave favorable treatment to the esnaf class and relied on its support. Correspondingly, he limited the role of the wealthy merchant class to paying prelacy taxes and funding initiatives without active participation. This could not fail to draw the ire of the wealthy [36]. Opposition to the interim prelate first appeared among the members of the Saint Sarkis Church board of trustees, who sought every opportunity to publicly repudiate Archbishop Pilibbos. One such opportunity was the visit to Diyarbekir of the emissary of the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate, Father Karekin Srvantsdyants, in September-November 1879 [37]. On the eve of Srvantsdyants’ departure from Diyarbekir, the board of trustees convened a meeting with his participation, and after hearing his impressions, suggested that he replace Archbishop Pillibos as prelate. News of this meeting soon spread, reaching the craftsmen of the city, and arousing their anger. A crowd gathered near the Saint Sarkis Church, demanding that Srvandsdyants immediately leave the city. Clashes erupted between Archbishop Pilibbos’ supporters and his opponents. Order was restored only after the intervention of the Turkish police. As a result of this event, many members of the Hayrenaser Society were arrested, and Zavzavatdjian was forced to go into hiding. As for Archbishop Pilibbos, he was escorted by the police to Constantinople to make an official statement [38].

The schools of Diyarbekir from the 1880s to the mid-1890s

“The state of education among Armenians is exceedingly unenviable.”

After these clashes, Armenian national-community life entered a period of relative stagnation, perhaps even of regression. Intra-community conflicts led to a series of interim prelates who quickly succeeded each other, some serving no more than a few months: Bishop Khoren Mkhitarian (March 1880-May 1880), Father Hovhannes Baghdasarian (June 1880-June 1881; April 1883-September 1885; 1888-August 1891), Father Yeghishe Kazandjian (June 1881-April 1883), Father Arisdages Tertsagian (September 1885-May 1886), Senior Priest Father Nerses Kharakhanian (1887-1888), and Bishop Yeznig Abahouni (August 1891-September 1891) [39]. The chaotic state of diocesan affairs also had its effect on the local educational system.

When Margos Natanian, a Western Armenian intellectual, visited the city in early 1895, he reported that the state of education in Diyarbekir was unenviable. In fact, not a single adequate school operated in the city. “Partisan disagreements, which have been festering since the time of Archbishop Pilibbos, still simmer, though not as intensely. There is no prelate, neither interim nor provisional, and no way forward,” Natanian concluded [40].

According to information from early 1896, from a report in the newspaper Armenia, the coeducational schools of the Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis churches still operated, alongside their kindergartens, in addition to the schools of the Hayrenaser and Antsnver societies. The combined enrollment in all these schools was 630 [41] (for detailed numbers for each of the schools, see the appropriate section of this article).

The majority of the teachers who taught in the schools of Diyarbekir were natives of the area and had graduated from the schools where they worked. Their monthly salary, depending on their schedule and level of classes they taught, was 25, 50, 60, 75, 120, or 150 kurus. None of the teachers working in Diyarbekir possessed a teaching certificate from the Constantinople Central Educational Council.

There was also no standardized educational program or curriculum. “Even a student transferring from one school to another that shared the same courtyard would have to unlearn everything and begin anew… There were no end-of-semester or final exams. No punishments for misbehavior or rewards for proper behavior. No separation between the grade levels, and no schedule of classes. It was a rarity for an entire class to learn together; usually, the teacher worked one-on-one with each student. There were no rules regulating the enrollment of new students, nor any questions for families who pulled their students from the schools. Schools gave the impression of pigeon coops – kids entering through one door and leaving out the other. No separation based on age, ability, health,” the same report stated [42].

The condition of the school buildings around Diyarbarkir was also dire: “The buildings were not designed to serve as schools at all. The larger buildings are too large and the smaller ones too small. All are built in the old style. They do not have facilities for separate study rooms, classrooms, and canteens. Just one room for the use of all,” wrote the same reporter [43].

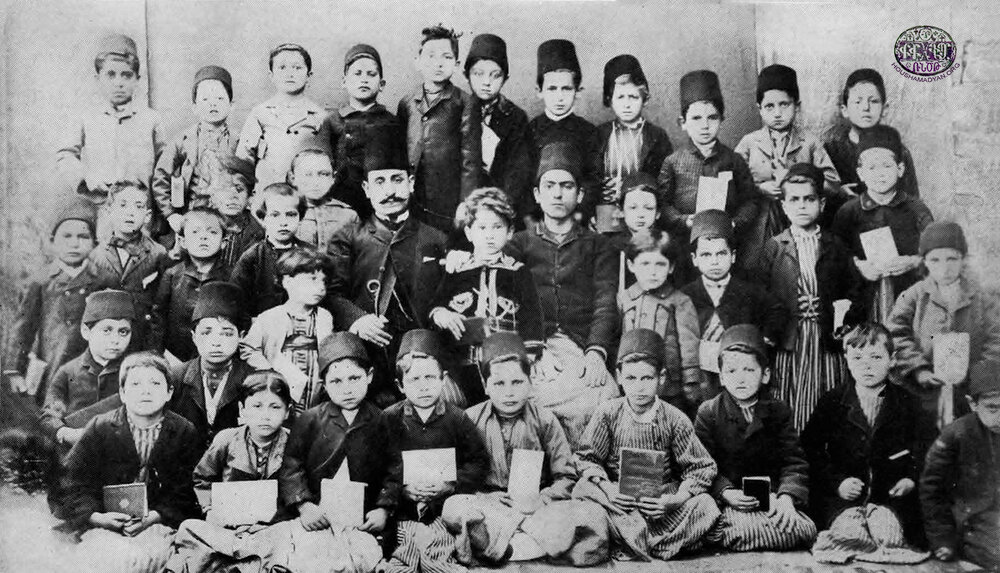

French researcher Vital Cuinet’s book, Asian Turkey (La Turquie d’Asie), provides a great deal of detailed information on the Armenian schools of Diyarbekir in the late 1880s and early 1890s. According to him, there were nine “national”-community and private Armenian schools operating in the city, five of which were Apostolic schools (four boys’ schools and one girls’ school); one was a Catholic boys’ school; and three were Protestant schools (two boys’ schools and one girls’ school). The combined enrollment of these schools was 490 pupils, of whom 380 were boys and 110 girls. A total of 300 pupils studied in Apostolic schools, 40 in the Catholic school, and 150 in the Protestant schools. The combined number of teachers was 20 (see Table 1 for a detailed breakdown of students and faculty by school) [44].

V. Cuinet also stated that the Apostolic schools were funded by each church’s parish community via a special tax, donations, and fundraising. Schools also charged tuition fees. The education that the pupils received was elementary. They were taught in two languages, Armenian and Turkish [45].

Table 1. Armenian schools in Diyarbekir in the late 1880s, according to figures provided by V. Cuinet

Community | Male | Female | ||||

Schools | Pupils | Teachers | Schools | Pupils | Teachers | |

Apostolic Armenian | 4 | 240 | 8 | 1 | 60 | 2 |

Catholic Armenian | 1 | 40 | 1 | - | - | - |

Protestant Armenian | 2 | 100 | 6 | 1 | 50 | 3 |

Total | 7 | 380 | 15 | 2 | 110 | 5 |

Diyarbekir’s Armenian schools from the mid-1890s to the 1908 Your Turk Revolution

“Results that were not seen in previous years.”

On 8 June 1895, Father Yezegiel Arsharouni was appointed interim prelate of the Diyarbekir Diocese. He served in that capacity until mid-1908 [46]. Arsharouni’s lengthy term played a positive role in the stabilization of “national”-community life in Diyarbekir and in defusing internal tensions.

The Hamidian massacres also played an important role in awakening Diyarbekir’s Armenians. According to accounts that appeared in the contemporary press, between the 20th and 22nd of October (1st to the 2nd of November) 1895, 2,000 Christians were killed and another 1,500 injured in the city of Diyarbekir and surrounding villages. The great majority of these Christian victims were Armenians. All of the city’s and sub-district’s churches and monasteries were damaged, and 1,200 stores and 1,500 homes belonging to Armenians were robbed. The total damage suffered by the Armenian community was calculated at approximately 10 million Ottoman pounds [47].

The economic downturn that followed the massacres also blighted Diyarbekir’s Armenian schools. Between 1896 and 1899, even the city’s most established community-“national” educational institution, the Saint Giragos parochial school, operated intermittently and irregularly, repeatedly closing its doors and reopening. In the spring of 1899, the majority of the its board of trustees resigned from their positions when faced with the reality that they would be unable to secure the financial means to maintain the school. Saint Giragos once again faced the threat of closure [48].

In the summer of 1899, Garabed effendi Der-Boghosian assumed the chairmanship of the board of trustees of the Saint Giragos School. The “capable” members of the newly elected board, “with commendable dedication and unimpeachable love for education,” were able to finally turn the tide and achieve the modernization of not only the Saint Giragos School, but also of the entire Armenian community-“national” educational system in Diyarbekir [49].

The new board selected the educator Bedros Srabian, a native of Keghi, as principal of the school. Srabian was described by contemporaries as “a serious man with an intimate knowledge of school reforms.” The existing faculty was supplemented with experts invited from the outside. The school’s costs increased in proportion to these reforms, reaching 3,000-4,000 kurus a month, which, according to a contemporary observer, was “unheard of in the annals in schooling in Diyarbekir” [50].

To raise the funds necessary to operate the school, the board of trustees resorted to a method that other Western Armenian institutions employed widely – the “patronage” system, whereby individual donors agreed to pay the tuition fees of one or several poor students [51].

According to an article published on 29 November (12 December) 1900 in Arevelk newspaper, the Saint Giragos parochial school, thanks to the efforts and its board of trustees and administration, had seen gradual improvements. New teachers, from well-known Western Armenian centers of education, had begun teaching at the school. Classes had begun as scheduled and continued to be held regularly. The faculty convened regular meetings, and one of its ongoing projects was the creation of a library [52]. The main challenge facing the board of trustees was securing the funds necessary to operate the school, as its budget ran a deficit of 10 Ottoman pounds per month. The board expected the help of the prelacy in resolving this issue. The Arevelk reporter suggested that the prelacy raise the funds by preaching the importance of education and schooling “not with the usual, dry exhortations of ‘Give, give!’, but by appealing to people’s emotions, by striking the fragile cords of the love for education in their hearts” [53].

An article dated 26 July 1901 joyfully reported that the Armenians of Diyarbekir “had never had a school as organized and well-run as Saint Giragos” [54]. Nevertheless, the article also stated that the school was in need of an additional 40-50 Ottoman pounds to “hold the final lessons for the graduating class and to ensure that the work of educating the young can proceed with even more regularity” [55].

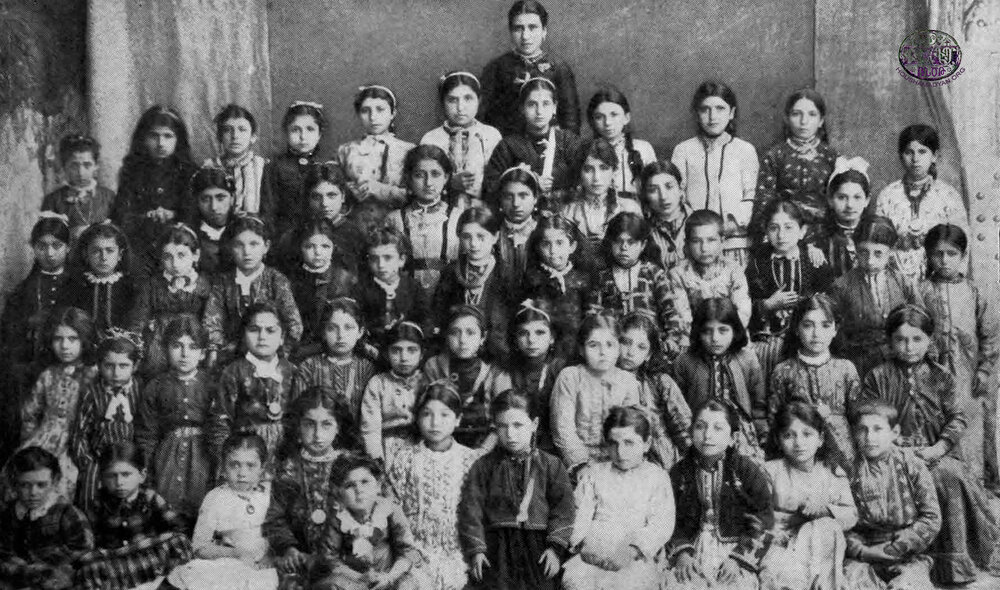

In another article from the same year, the results achieved by the Saint Giragos girls’ school are described as “exceeding many people’s expectations … Unprecedented results that were not seen in previous years” [56]. To graduate from the school, students had to pass examinations in Armenian, religious studies, grammar, and home economics. The article noted that these subjects were taught to the girls using an “effective pedagogical method” [57].

Graduates from Armenian schools in Diyarbekir received their diplomas in solemn ceremonies, held in the courtyard of the respective neighborhood church. These ceremonies would be attended by the diocese prelate, prominent members of the community, representatives of the city’s Catholic and Protestant communities, and the general public [58].

The results achieved by the Saint Sarkis School were less satisfactory. On 20-22 October 1895, during the Hamidian massacres, the church was looted and suffered significant damage. As a result, its school did not operate at all in 1896-1897. In 1898, the church and school were reopened, but the school’s board of trustees failed to properly manage its affairs. Specifically, it failed to secure competent teachers, as a result of which there was a constant trickle of students leaving the school [59].

The prelate, who was troubled by the dire state of the Saint Sarkis School, commissioned Bedros Srabian, the principal of the Saint Giragos School, to investigate the situation and to recommend reforms. According to the report that Srabian submitted, the Saint Sarkis School, at the time, had 57 male and 45 female pupils; and three male and two female teachers. Among the notable problems were the inappropriate separation of grade levels; the lack of alignment of the curriculum with the guidelines of the Central Educational Council; irregularities in the student rosters and records; the use of obsolete textbooks; the lack of internal oversight; the lack of discipline; etc. [60].

To address the situation, Srabian recommended that all students of the school be given detailed exams, after which, according to the results, new classes would be created; a new educational program would be formulated; appropriate textbooks would be distributed; new desks, chairs, and other equipment would be procured; and, most importantly capable and conscientious teachers would be invited to work at the school [61]. Evidently, most of these recommendations were implemented over time.

Another valuable source of information on the schools of Diyarbekir during this period is the Constantinople Patriarchate’s National Central Executive Board’s educational committee’s report on “national”-community schools in Ottoman provinces, prepared in 1901. According to this document, the Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis coeducational schools alone had an enrollment of 884 pupils (560 male, 324 female) and a faculty of 25 teachers (16 male, 9 female) [62] (for detailed information on each school, see the appropriate section of the article). According to the same report, the combined enrollment of the Diyarbekir Armenian Catholic and Protestant schools was 190 Armenian pupils (90 male, 100 female) [63].

None of the villages of the Diyarbekir sub-district had operational Armenian grammar schools. However, the prelacy intended to open one school in each [64].

An important event in the history of education in Diyarbekir was the reopening of the Sunday school for young craftsmen, in the fall of 1902, by the prelacy. The subjects taught included Armenian, Turkish writing; and when possible, French and English, religion, mathematics, writing, and “moral instruction.” The classes were held in the building and courtyard of the Saint Giragos School. Initially, the management of the Sunday school was entrusted to Father Krikor Hakimian, the church priest, and four teachers working in the Saint Giragos School. But the large number of enrollees who appeared on the first day of classes forced the school’s board of trustees and administration to become actively involved [65].

Approximately 100 youth attended these Sunday school classes. No tuition fees were charged. Each student was asked to voluntarily pay whatever amount he could. The board of trustees was required to use these voluntary fees to procure books and newspapers for the school or to establish a school library [66].

It was in the early 1900s that attempts were made to open Armenian schools in some of the larger Armenian-populated villages of the Diyarbekir sub-district. To wit, in 1901, “thanks to the generous contributions of a philanthropist,” a school was opened in the village of Sat (which, according to figures from 1913, had a population of 70 Armenian households). The school was soon the source of “great solace for the rural community” [67]. This school, and others that were opened in the villages of the sub-district in future years, operated intermittently, opening and closing depending on the availability of funds and qualified teachers.

The schools of Diyarbekir after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution: The Harachtimagan [Progressive] Secondary School

“Still, there’s much to be done in the field of education in Diyarbekir.”

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution ushered a period of significant progress in all domains for the Armenians of Diyarbekir, including the field of education.

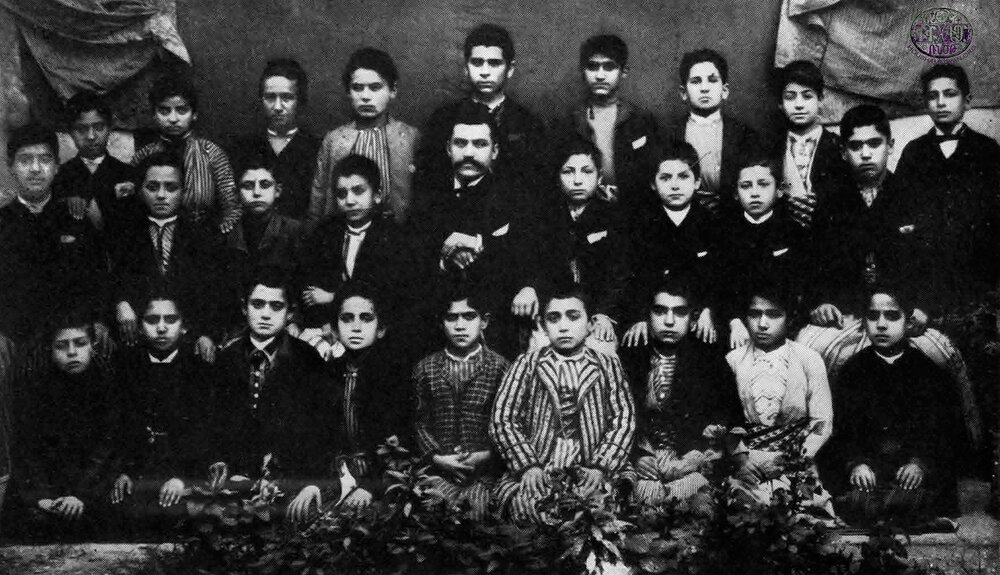

An important milestone in the history of education in Diyarbekir was the founding, in 1909, of its first secondary school. This was a private institution named the Harachtimagan [Progressive] School. It operated with a license from the Ottoman Ministry of Education. It was founded by a “group of capable” activists, led and brought together by Dr. Hovhannes Terzian [68] [69].

The school had eight grade levels, six of which used the standardized educational program, and two of which were exclusively technical/pedagogical, designed to train “well-prepared and qualified” teachers who would serve in the “backward” villages of Diyarbekir sub-district [70].

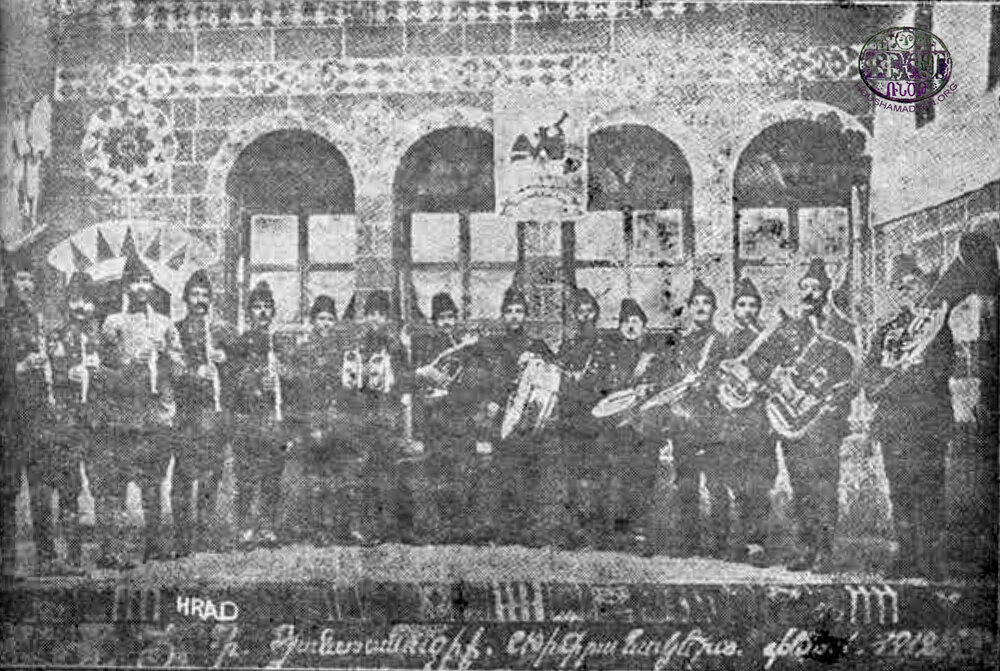

The school employed modern teaching methods befitting its name. The faculty included teachers (almost all of them members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, Dashnak Party)) who had been invited from Constantinople, Kharpert/Harput, Garin/Erzurum, Aintab, and even Eastern Armenia. Among these teachers, the most influential thanks to his age and experience was Haroutyun Kasparian, from the Caucasus. In order to ensure cooperation between the community, the parents, and the school, regular faculty and parent-school conferences were organized [71].

With the help of its supporters, both local and abroad, the school was gradually able to obtain proper furniture and to create a library that, through small, included first-rate titles. The school also received support from local educational-“cultural” organizations, Diyarbekir Armenians who had emigrated, and groups of “supporters” in various corners of Western Armenia. For example, on 30 September 1912, the supporters of the Harachtimagan Society organized a public movie viewing (“cinematographic presentation”). The funds raised by this event were used entirely to support the needs of the Harachtimagan School [72].

The Harachtimagan School was held in high esteem by the local Armenian population. One contemporary wrote that “it promised to become a new Sanasarian [73] in the heart of our province” [74].

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution marked the start of a period of great activity for the educational-“cultural” organizations of Diyarbekir. On 1 September 1908, the Dikranagerd Armenian Scholastic Society was founded. Its mission was to “use every available means” to support education and schooling in the city’s and the sub-district’s villages (“To encourage all initiatives that have the potential to secure the necessary moral and intellectual progress of the people … To establish daily schools (in the villages), Sunday schools, and night schools; to open libraries, reading rooms, lecture halls; to organize events appropriate for each time and place”) [75]. In 1909, the “educational” committee of the society, “thanks to its ceaseless and determined efforts and the generous support of its contributors,” paid the tuition fees of 40 indigent pupils, and also opened a school in the village of Hayeghig (according to figures from 1913, the village had an Armenian population of 20 households). The society planned to continue opening schools in the large Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district [76].

In 1908, the Yeridasartats [Youth] Society was formed in the Saint Sarkis neighborhood. It was an educational-“cultural” society, and in that same year organized Sunday classes and evening lectures for the public [77].

In 1909, the Hayouhyats [Armenian Women] Society was founded, to operate alongside the girls’ division of the Saint Giragos parochial school. The society secured the use of a meeting hall and organized Sunday lectures for the public [78].

At around the same time, members of the Catholic Armenian community of Diyarbekir founded the Zarkasirats [Progressive] Society, and members of the Protestant community founded the Grtasiratrs [Educational] Society, both of which actively pursued their aims in the field of education [79].

Also after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in 1909, students of the highest grade level of the Saint Giragos School, the fifth and sixth graders, formed their own educational society, which launched several initiatives (including the school’s own library/reading room, with subscriptions to various Armenian newspapers) [80]. Members of the society also published Araks, a hectograph paper [81].

With the support of the Scholastic Society, the students of the Saint Giragos parochial school also found the courage to present their many demands to the school administration, and to organize walk-outs and student strikes to campaign for their rights [82].

The actions of the Scholastic Society were met with some trepidation by the administration of the local schools and the Central Educational Council. In early 1910, the members of the Council were Pilibbos Arpiarian (chairman), Kourken Barsamian (secretary), Boghos Teghdarian (treasurer), Hagop Keatibian, Hagop Ghazigian, Giragos Ghazaz-Bezazian, Hovhannes Daghlian, and Dikran Bekdjibashian [83]). The Council demanded that the Society present all of its plans to it for approval [84].

In January of 1910, Senior Priest Father Zaven Der-Yeghiayan was appointed interim prelate of the Diyarbekir Diocese. Upon his arrival in the city, he began regularly visiting the city’s “national” schools; acquainted himself “seriously and methodically” with the issues they faced; and proposed solutions, chief among which was the construction of new school buildings [85].

The interim prelate also organized a series of regular lectures on various subjects of public interest at the Saint Sarkis Church and its school. The lectures were scheduled on Mondays for men, and on Wednesdays for women. Events of educational/religious nature were also held, with the participation of invited guests. To wit, on 21 February 1910, the Saint Giragos Church hosted lectures by Zaven Der-Yeghiayan himself and Ferid Djemil (Dikran Amseyan), the latter a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and a teacher. The lecture focused on “the importance of schools and the imperative of improving them” [86].

Zaven Der-Yeghiayan’s abovementioned initiatives prompted journalist Levon Srabian to describe the newly appointed interim prelate as “practical and a master of administration … Not prone to empty demonstrative acts. He who will continue to rise and achieve” [87].

According to Levon Srabian, aside from the construction of new school buildings, other urgent problems in the field of education in Diyarbekir in 1910 were the absence of a coeducational kindergarten, the need for additional subjects in the schools’ curricula, and the need for better-qualified principals [88].

In another article, Levon Srabian emphasized the importance of the adoption of internal bylaws by the Armenian schools, which would codify “the prerogatives and the relationships between the students, the faculty, the boards of trustees, the Educational Council, and the community.” He also underlined the importance of the creation of an educational program that would specify the number of subjects taught per grade level and the required quality of instruction, alongside “a consistent application of educational methods” [89].

The Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate’s 1913 report provides detailed information on the state of the Armenian educational system in Diayarbakir on the eve of the Genocide. According to this report, at the time, there were 11 “national”-community schools operating in the sub-district of Diyarbekir, of which 9 were boys’ schools and two were girls’ schools. The report did not list schools per city or village, but we can safely assume that four of them (two boys’ and two girls’ schools) were located in the city of Diyarbekir (the Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis boys’ and girls’ schools). The other seven were most probably the boys’ primary schools located in some of the larger Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district. The combined enrollment in all these schools was 1,300 (no gender breakdown provided) [90]. For comparison, the figures from 1901 indicate that the only community-“national” schools operating in the sub-district were located in the city of Diyarbekir (the Saint Sarkis and Saint Giragos boys’ and girls’ schools), with a combined enrollment of 884 pupils.

As in other parts of Western Armenia, the further development of the educational system in Diyarbekir came to a screeching halt when the Armenian Genocide began. Alongside the rest of the Armenian residents of Diyarbekir, the city’s Armenian intellectuals were exterminated. Among the victims of the Genocide were 48 male and female teachers who worked in the Armenian Apostolic, Catholic, and Protestants schools of Diyarbekir [91]. A total of 30 were teachers who worked in the Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis parochial schools [92].

Armenian schools operating in the city of Diyarbekir in the second half of the 19th Century and early 20th century

The Saint Giragos parochial, coeducational school

The first recorded mentions of the Saint Giragos coeducational school date from the 1850s.

According to the Vidjag Azk.[ayin] Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi [The State of National Schools and Societies in Dikranagerd], dated 13 April 1879, and which reproduced facts from local sources, the school’s kindergarten had an attendance of 160 pupils, with only one teacher, Tovmas agha Soghramadjian, who had been teaching at the school for 14 years. The number of pupils in the boy’s upper section was 24. They were taught Armenian by Garabed Basmadjian, who had been teaching at the school for four years [93]. The girls’ upper section had a total enrollment of 150 pupils. They were taught Armenian, embroidery, and needlework [94]. According to these figures, the total number of boys and girls enrolled in the school in 1879 was 334.

According to figures from early 1886, total enrollment in the boys’ section of the kindergarten was 200, and of the boys’ upper section was 70. The total number of girls enrolled in the school was approximately 100 [95], for a total enrollment of 370 pupils.

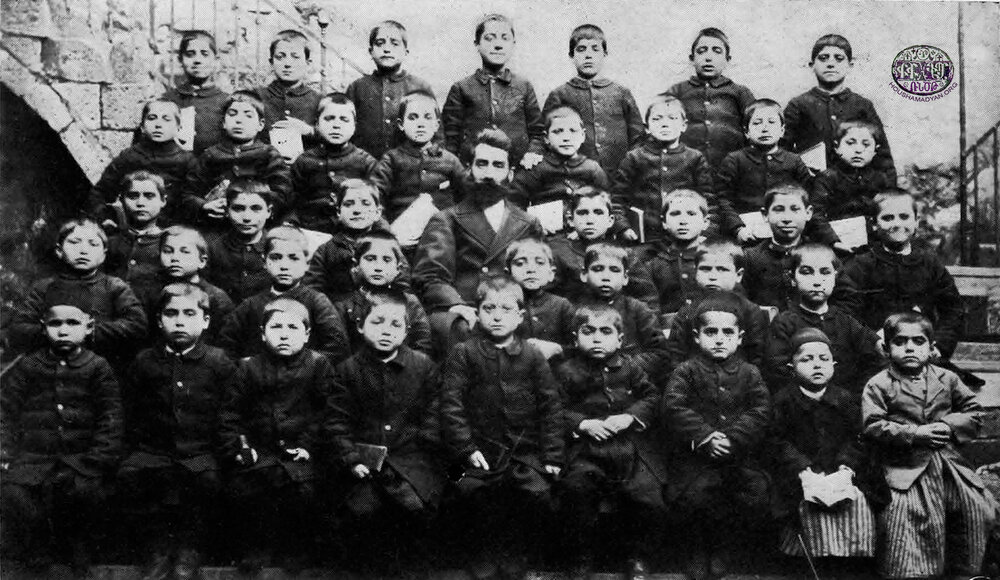

According to the 1901 report prepared by the Central Educational Council, the Saint Giragos parochial school offered a six-year course of education (grades “A through F”): kindergarten and preparatory grades, grammar school, and the upper grades. In the 1900-1901 schoolyear, total enrollment stood at 754 pupils (480 boys, 274 girls), under the care of 20 teachers (13 male, 7 female). The monthly expenses of the school totaled 2,900 kurus, which came from the neighborhood council’s budget (608.5 kurus), tuition fees (1,425 kurus), and various gifts and donations (866.5 kurus) [96]. Interestingly, the school’s Ottoman Turkish teacher received his or her salary (1,800 kurus) from the local Ottoman authorities [97].

Garo Sassouni, the celebrated Armenian intellectual, served as a young teacher between 1906-1908 first in the Saint Sarkis School of Diyarbekir, then in the Saint Giragos School (in 1906, Sassouni was only 17 years old). In his memoirs, he wrote that at the time, the total number of students enrolled in the Saint Giragos School was 1,200. The faculty consisted of 36 male and female teachers, and the school had a large library with a collection of 6,000 volumes. Sassouni wrote that his salary as a teacher was one Ottoman pound, which “was enough for a single man to live well” [98].

The Saint Sarkis parochial, coeducational school

The first recorded mentions of the Saint Sarkis coeducational school date from the 1870s. According to the figures of the 13 April 1879 report, the school had an enrollment of 24 pupils. The teacher was Dikran Varjabedian, who taught Armenian, Armenian history, and Ottoman Turkish [99].

According to figures from early 1886, the Saint Sarkis parochial school already had a kindergarten, as well as boys’ and girls’ sections. Total enrollment stood at approximately 200 pupils, of whom about 100 were enrolled in the kindergarten, 40 in the boys’ section, and 60 in the girls’ section [100]. Between 1885 and 1888, the principal of the school was Tovmas Zavzavatdjian, who had returned to Diyarbekir. According to a contemporary source, Zavzavatdjian had given the school “a stamp of excellence, and to a certain extent it overshadowed the Saint Giragos School and poached some of its most important pupils” [101].

According to the figures from the 1901 report, the Saint Sarkis School offered a four-year course of education (grades “A through D”). It had an enrollment of 130 pupils (80 boys, 50 girls). The faculty consisted of five teachers (3 male, 2 female). The monthly expenses of the school totaled 400 kurus, of which 309 came from the neighborhood budget, 83 from tuition fees, and 8 from gifts and donations [102].

According to Garo Sassouni, who taught at the Saint Sarkis School, then the Saint Giragos School between 1906 and 1908, the Saint Sarkis parochial school had an enrollment of 350 pupils (of both sexes). At the time, the school’s principal was the celebrated local intellectual and author Hagop Papazian [103].

The coeducational school of the Hayrenaser (Hayrenasirats) Society

The school of the Hayrenasirats Society was founded in 1865 by Tovmas Zavzavatdjian, a member of the society, and other local “devotees of education.” In the year of its founding, the school had an enrollment of 40 pupils. Zavzavatdjian himself taught Armenian using “the most modern methods.” Aside from him, the school’s faculty also included Simeon Hekimian (from Sepasdia/Sivas, taught Armenian and French) and Deacon Bedros Atamian (from Chmshgadzak) [104].

The school was closed in early 1872, then re-opened in the fall of 1874 (see the appropriate section of this article for additional details). According to figures from April 1879, it had an enrollment of 25 pupils and a faculty consisting of three teachers: Tovmas Zavzavatdjian (taught Armenian), Bedros Djerahian (taught French), and Garabed Khandanian (taught Ottoman Turkish). The school also had a library with a collection of 100 volumes [105].

According to figures from early 1896, the school had an enrollment of 40 pupils [106]. Classes were held in the building of the Saint Giragos School [107].

Our sources do not provide additional information regarding this school and its operations in subsequent years.

The school of the Antsnver Society

The Antsnver Society’s Diyarbekir chapter was founded in 1868 thanks to the efforts of Mgrdich Ekmekdjian, the prominent local educator and pedagogue. The society’s school was founded in the same year, alongside a free Sunday school designed for local craftsmen. The combined enrollment in both institutions was 70, with a combined faculty of 12 [108].

The school’s classes were held in the building of the Saint Sarkis School [109].

According to figures from 13 April 1879, the school had an enrollment of 30 pupils, under the care of pedagogue/principal Krikor Hekimian. An additional 50 people were enrolled in the craftsmen’s Sunday school. These adults attended various lectures on “national” issues, aimed at “cultivating and edifying the minds of the masses.” Among the Society’s other initiatives was the Srpazan Tarkmanchats (Holy Translators) Library, with a collection of 400 volumes [110].

According to figures from early 1886, the Antsnver Society’s school had an enrollment of 20 pupils [111].

Our sources do not provide additional information regarding this school and its operations in subsequent years.

The school of the Mesrobian Society

The Mesrobian Society was founded in 1877 by several prominent individuals who lived in the Saint Sarkis neighborhood. Its aim was to found a school in the same neighborhood. According to figures from April 1879, the Mesrobian Society’s school had an enrollment of 30 pupils. Efforts were being made to improve the quality of instruction it provided [112].

The school’s classes were held in the building of the Saint Sarkis School [113].

Our sources do not provide additional information regarding this school.

The Protestant schools of Diyarbekir

The Protestant church of Diyarbekir was founded in 1851 by American missionaries Azaria Smith and George and Susan Dunmore [114]. A school was also opened alongside the meeting hall. The children of local Armenians who had embraced Protestantism soon flocked to this school. In the early 1860s, a Protestant Sunday school also operated in the city, and provided religious instruction to 284 believers in 1862, with this number rising to 339 by 1865 [115].

According to the figures provided by V. Cuinet, three Protestant schools operated in Diyarbekir in the early 1890s, two of which were boys’ schools, and one a girls’ school. The boys’ schools had a combined enrollment of 100 pupils, and a combined faculty of six teachers. The girls’ school had an enrollment of 50 pupils under the care of three teachers. The Armenian Protestant schools were associated with the American Protestant missions. The schools’ educational programs reflected the local limitations. The educational level of the teachers was not particularly high. Classes were held in Armenian, Turkish, and English [116].

Aside from the abovementioned schools, records indicate that a Protestant girls’ secondary boarding school was founded in Diyarbekir in 1882 [117].

According to figures from 1903, four teachers were working in Diyarbekir’s Protestant schools. Among them was head teacher Haroutyun Dikidjian, a graduate of the Aintab American College [118].

The Catholic schools of Diyarbekir

According to V. Cuinet, there was one Armenian Catholic school in Diyarbekir in the 1890s. It was a boys’ school, with an enrollment of 40 pupils under the care of a single teacher. However, dissatisfied with the level of instruction at this school, many of the local Armenian Catholics sent their children to the Latin Catholic schools that operated in the area. One of these was established by two Italian members of the Capuchin Order, and it provided relatively decent elementary education in the Armenian, Turkish, and Italian languages. Another of these schools was headed by four Franciscan nuns, and provided education in Armenian, Turkish, and French. These schools were open not only to Armenian Catholics, but to children who belonged to all Christian denominations and nationalities [119].

According to figures from 1903, the local Catholic school had one teacher. However, the Catholic community, “understanding the necessity of having a better-regulated school,” planned to expand the existing school and had already budgeted about 100 Ottoman pounds per year for this purpose [120].

- [1] H. H. Khoutanian, “Hnakuyn Aghtsniki Deghakroutyan yev Dndesoutyan Masin” [“On the Geography and Economy of Ancient Aghtsnik”], Lraper Hasaragagan Kidoutyunneri, 2014, number 2, p. 62.

- [2] Madteos Purhayetsi, the 11th-12th century Armenian chronicler, writing about the campaign launched by Byzantine general Mleh-Demesligos in 927-928 CE against the Arab Caliphate, wrote that the general assaulted the city of Dikranagerd, built on the banks of the Tigris River, which was also called Amit (see Madteos Purhayetsi, Jamanagakroutyun [Chronicle], Yerevan, 1973, p. 10). The Armenian historians of the Middle Ages, following the example of Movses Khorenatsi, attributed the founding of Dikranagerd to Dikran Haygazoun, who ruled in the sixth century BCE.

- [3] Yervant Kasouni, Amit (Diyarbekir)-Dikranagerd (Farghin) Shpotu Hay Badmakroutyan Mech [The Confusion between Amit (Diyarbekir)-Dikranagerd (Farghin) in Armenian Historiography], Beirut, 1968, p.34.

- [4] T. Kh. Hagopian, S. D. Melik-Pakhshian, H. Kh. Parseghian, Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri Deghanounneri Pararan [Dictionary of Place Names of Armenia and the Surrounding Area], volume 2, Yerevan, Yerevan State University, 1988, p. 100.

- [5] Suavi Aydın and Jelle Verheij, “Confusion in the Cauldron: Some Notes on Ethno-Religious Groups, Local Powers and the Ottoman State in Diyarbekir Province, 1800–1870,” Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915, Joost Jongerden and Jelle Verheij (ed.), Leiden-Boston, BRILL, 2012, p. 21.

- [6] Raymond H. Kévorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la Veille du Génocide [The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide], ARHIS, Paris, 1992, pp. 59 and 397-398; Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and its Flock's Catastrophic Year of 1915], New York, 1985, pp. 264-265.

- [7] Vidjagatsoutys Dikranagerdi Temin, 1913 [Report on the Diocese of Dikranagerd, 1913], Archives of the Noubarian Library of Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), Paris, ABC/BNu, DOR 3/2, f. 47.

- [8] Teotig, Koghkota…, p. 264.

- [9] Kegham M. Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani Badmajoghovrtakragan Ngarakiru Medz Yegherni Nakhoreyin” [“The Ethno-Demographic Character of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide”], Part 9: Diyarbekir Vilayet, Diyarbekir Sanjak, and the Sub-Districts of Mardin and Djezire, Vem Pan-Armenian Journal, year 12 (18), number 1 (69), January-March 2020, p. 159.

- [10] Teotig, Koghkota…, p. 264.

- [11] Hagopian et al., Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, volume 2, p. 101.

- [12] Archbishop Maghakia Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin yev ir Badmoutyunu, Vartabedoutyunu, Varchoutyunu, Paregarkoutyunu, Araroghoutyunu, Kraganoutyunu, ou Nerga Gatsoutyunu [The Armenian Church and its History, Priesthood, Administration, Reforms, Rituals, Literature, and Current State], Constantinople, 1911, p. 263.

- [13] Hagopian et al., Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri…, volume 2, p. 101.

- [14] The Armenian-populated neighborhoods around Saint Giragos were Fatteh Pasha, Karib Kastal, Khanchapag, Sheikh-Matar, Geavour Meydan, Hormnouts, Chrik (Upper and Lower), Pous Koucha, Chardukhli, Upper Fourdji Koucha, Ardabash, Alibardagh, etc. The Armenian neighborhoods around Saint Sarkis were Pous Koucha, Marhabba Klokh, Geavour Kouchasi, Markozma, Dava Kalduran, Lelebeg, Bekir Pasha, Sineg Bazar, and Loulanire (Kaghkutsi, “Yeraneli Orer” [“Wonderful Days”], Dikris Yearbook, Published by the Dikranagerd Compatriotic Union, Aleppo, Dikris Printing House, Vartkes Krikorian, 1946, p. 34).

- [15] T. Azadian, Haruramya Hopelyan Bezdjian Mayr Varjarani. Kumkapı. 1830-1930 [Centennial Jubilee of the Bezdjian School. Kumkapı. 1830-1930], Constantinople, 1930, p. 14.

- [16] Ratified by the Ottoman government in 1863.

- [17] Organizations that operated in Western Armenia with the objective of helping the community in various ways were called “cultural” organizations.

- [18] Azkayin Sahmanatroutyun Hayots: Hasdadyal 1863 yev Veraknyal [The National Constitution of Armenians: Ratified in 1863 and Revised], Cairo, Arshalouys Newspaper Press, 1901, p. 33.

- [19] Ibid., pp. 41-42.

- [20] Levon Chormisian, Hamabadger Arevmdahayots Meg Tarou Badmoutyun [An Overview of a Century of Western Armenian History], Volume 1, 1850-1878, Beirut, 1972, pp. 525-526.

- [21] Masis Political, National, Linguistic, and Economic Journal, Constantinople, 25 April 1857.

- [22] Ibid.

- [23] Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker [Echoes of Amida], New Jersey (USA), 1950, p. 322.

- [24] Ibid.

- [25] “Vidjag Azk.[ayin] Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi” [“The State of National Schools and Societies in Dikranagerd”], Terdjeman Efkyar, Constantinople, 7 May 1879.

- [26] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 158.

- [27] Ibid., p. 159.

- [28] Ibid., p. 160; Yeghishe G. Debaghian, “Tovmas B. Zavzavatdjian (Mkhitar Amtetsi) (1842-1911),” Nor Dikranagerd Ethnographic, Geographic, Historical, and Literary Bimonthly, New York, April 1939, number 3, p. 6.

- [29] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 160.

- [30] Ibid., p. 314. Also, Armenia National, Political, and Commercial Newspaper, Marseille, 3 October 1894.

- [31] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 161.

- [32] In the 1860s-1870s, the Ottoman authorities exiled numerous Bulgarian nationalist activists to Diyarbekir. The local Armenians were well-acquainted with them and their activities (Овнанян С.В., «Из истории армяно-болгарской дружбы», Historical-Rhetorical Review, 1967, 2-3, pp. 303-313).

- [33] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 161.

- [34] Ibid., p. 165.

- [35] Terdjeman Efkyar, 7 May 1879.

- [36] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 165.

- [37] Srvantsdyants was dispatched to Western Armenia to study the conditions of the Armenian population there and to prepare a report on its demographic and other characteristics (for additional details, see Robert Tatoyan, Arevmdahayoutyan Tvakanagi Hartsu 1878-1914 Darineroun [The Problem of Determining the Western Armenian Population in the Years 1878-1914], Yerevan, Museum of the Armenian Genocide, 2015, p. 81; and Emma Gosdantian, Karekin Srvantsdyants, Yerevan, Science Academy of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1979, p. 117).

- [38] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, pp. 165-167. For an account of these events from Karekin Srvantsdyants’ perspective, see K. Srvantsdyants, Toros Aghpar [Brother Toros], Part B, Constantinople, 1885, pp. 218-220. It’s worth noting that later, when Archbishop Pilibos was appointed Prelate of the Baghdad Diocese (in 1883), he invited Tovmas Zavzavatdjian to teach in the local parochial schools that had just reopened (see Debaghian, Tovmas Z. Zavzavatdjian, p. 7).

- [39] This list of prelates of Diyarbekir is based on information from the following sources: Armenia Newspaper, Marseille, 12 August 1885, number 3, p. 12; Armenia Newspaper, 29 May 1886, number 81, p. 2; Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker, p. 202.

- [40] Margos Natanian, “Dikranagerd gam Amit” [“Dikranagerd or Amit”], Masis Journal, Constantinople, 4 May 1885, number 3768, p. 970.

- [41] Armenia Newspaper, Marseille, 6 January 1886, number 42, p. 2.

- [42] Armenia Newspaper, Marseille, 6 January 1886, number 42.

- [43] Ibid.

- [44] Vital Cuinet, La Turquie D’Asie [Asian Turkey], volume 2, Paris, 1981, p. 455.

- [45] Ibid., p. 457.

- [46] For the date of the start of his term, see Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker, p. 203. We estimated the length of his term based on information from different years’ issues of Untartsag Oratsuyts S. Prghchian Hivantanots Hayots[Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital].

- [47] A resident of Dikranagerd, “Deghegakir Dikranagerden” [“A Report from Dikranagerd”], Armenia Newspaper, Marseille, year 11, number 56, 15 February 1896.

- [48] Hagop B. Papazian, “Grtagan Kordzu Dikranagerdi Mech” [“The Work of Education in Dikranagerd”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, number 4989, 4/17 July 1902.

- [49] Ibid. The board of trustees was still in office, under the leadership of Garabed Der-Boghosian, until the summer of 1902 (see A Devotee of Education, “Diyarbekiri Grtagan Kordzu” [“Educational Work in Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, July 3/16 1903, number 5297). Another source described Der-Boghosian as a man of work, who “despite being involved in various commercial enterprises, deeply understood the value of schooling… He devoted a significant amount of his time to the cause of education. He discussed, consulted, appealed, and often worked alone, always exhibiting great modesty. He was one of the selfless men who, with their own personal efforts, prevented the complete collapse of the educational system in the city and formulated the plan to completely re-organize the city’s schools” (Levon Srabian, “Kavari Oushakrav Temkeru” [“The Prominent Figures of the Provinces”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 6/19 March 1903, number 5197).

- [50] Papazian, “Grtagan Kordzu Dikranagerdi Mech,” 1902, number 4989.

- [51] Ibid.

- [52] M. Tanielian, “Diyarbekiri Kordzer” [“Affairs of Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 29 November (12 December) 1900, number 4494.

- [53] Ibid.

- [54] Sharour, “Diyarbekiri Varjaranneru” [“The Schools of Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 30 August (12 September) 1901, number 4727.

- [55] Ibid.

- [56] Pelag, “Antranig Shrchanavardneru Diyarbekiri Varjaranen” [“The Inaugural Graduating Class of the Diyarbekir School”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 21 August (3 September) 1901, number 4719.

- [57] Ibid.

- [58] For a description of the graduation ceremony at the Saint Giragos School held at the conclusion of the 1901-1902 schoolyear, see Hagop Papazian, “Grtagan Hantes Diyarbekiri Mech” [“An Educational Celebration in Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 6 (19) August 1902, number 5017.

- [59] Hagop Papazian, “Grtagan yev Yegeghetsagan Kordzu Diyarbekiri mech,” [“The Work of Education and the Church in Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 18 September (1 October) 1902, number 5092.

- [60] Papazian, “Grtagan Kordzu Diyarbekiri Mech,” Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 1 (14) November 1902, number 5092.

- [61] Ibid.

- [62] Vidjagatsouyts Kavaragan Azkayin Varjaranats Tourkyo. Badrasdyal Ousoumnagan Khorhrto Azkayin Getronagan Varchoutyan. Dedr. A. Vidjag 1910 Darvo [Report on the Provincial Armenian Schools in Turkey. Prepared by the Central Executive Board of the National Educational Council. Book A, Report on the Year 1910], Constantinople, H. Madteosian Press, 1901, p. 17.

- [63] Ibid.

- [64] Ibid.

- [65] Hagop B. Papazian, “Giragnorya Varjaran Diyarbekiri Mech” [“Sunday Schools in Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 17/30 October 1902, number 5079.

- [66] Ibid.

- [67] Hagop Papazian, “Grtagan Kordzu Diyarbekiri Temeroun Mech” [“The Work of Education in the Parishes of Diyarbekir”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 3/16 August 1902, number 5015.

- [68] Hovhannes Terzian (1883-1915) was a doctor by profession, and a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). He was born in Diyarbekir, and had received his early education at the Saint Giragos parochial school, after which he had matriculated at the Euphrates College in Kharpert and the medical school of the American University of Beirut. While studying at the university, he had become a member of the ARF. In 1910, he returned to Diyarbekir and began practicing medicine. He actively participated in Armenian life in the city, serving as a member of the executive committee of the ARF chapter of Dikranagerd. In 1912-1913, he participated in the Balkan Wars as a member of the Ottoman Army. He was called up to the army again upon the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, serving as a colonel in the Erzincan military hospital. He was killed in July 1915 (for more details on Hovhannes Terzian, see Nora Parseghian, “Badarigner Dikranagerdtsi Terzian Undaniki Badmoutenen ou Hbardoutenen” [Fragments of the History and Pride of the Terzian family of Dikranagerd], Aztag Daily, accessed online at http://archive.aztagdaily.com/archives/72809).

- [69] H. K., “Dikranagerdi Harachtimagan Varjaranu” [“The Harachtimagan School of Dikranagerd”], HarachCommunity, Economic, Political, and Literary Newspaper, Garin, 29 September 1912, p. 107.

- [70] Ibid.

- [71] H. K., “Dikranagerdi Harachtimagan Varjaranu…”; also, Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakankerou Veragochoumn yev Pen Hador [The Recalling of the Echoes of Amida and the Second Volume], New Jersey, 1953, p. 332.

- [72] Ibid.

- [73] A reference to the famous Sanasarian School in Erzurum.

- [74] Kaghkutsi, “Yeraneli Orer,” p. 34. The Harachtimagan School remained open until mid-1913, when it was forced to close due to financial difficulties (Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker, pp. 153 and 332).

- [75] “Dikranagerdi Hay Ousoumnasirats Ungeroutyan Nbadagn ou Dzrakiru” [“The Goal and Program of the Scholastic Society of Dikranagerd”], Armenia Newspaper, Marseille, 16 December 1908, number 20.

- [76] Keghchoug, “Khabrigner Yergren” [“News from the Country”], Azadamard Newspaper, Constantinople, 5/18 January 1910, number 177.

- [77] Yeprem V. Boghosian, Badmoutyun Hay Mshagoutayin Ungeroutyunnerou [History of Armenian Cultural Societies], volume 2, Vienna, Mkhitarine Order Press, 1963, p. 451.

- [78] Ibid., p. 452.

- [79] Ibid., p. 451. Levon Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen” [From the Banks of the Euphrates], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 18 (31) March 1910, number 7282.

- [80] Ibid., p. 452.

- [81] Azadamard Newspaper, Constantinople, 26 March (8 April) 1910, p. 243. This was not the first attempt to publish an Armenian periodical in Diyarbekir. After the Young Turk Revolution, various periodicals and papers succeeded each other with “meteoric speed” at the Saint Giragos School. Among these was a journal published by Levon Srabian, one of the teachers, entitled Kragan Karoun [Literary Spring] (Levon Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen”).

- [82] For the description of a specific incident in December 1909 when students came out in protest against their teacher, see Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen,” Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 19 March (1 April) 1910, number 7283. For a description of another protest organized by students against a teacher, see Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen,” Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 15 (28) July 1910, number 7365.

- [83] Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen,” Arevelk Newspaper, number 7283.

- [84] Azadamard Newspaper, number 243.

- [85] Srabian, “Gyanku Kavarin Mech. Dikrisi Aperen” [“Life in the Provinces. From the Banks of the Euphrates”], Arevelk Newspaper, number 7246.

- [86] Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen,” Arevelk Newspaper, number 7283.

- [87] Srabian, “Gyanku Kavarin…,” Arevelk Newspaper, number 7246.

- [88] Ibid.

- [89] Levon Srabian, “Dikrisi Aperen,” Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 10 (23) July 1910, number 7361.

- [90] Report on the Diyarbekir Diocese, 1913 (AGBU Noubarian Library Archives, Paris, ABC/BNu, DOR 3/2, f. 47).

- [91] T. Mgrdichian, Dikranagerdi Nahanki Charteru yev Kurderou Kazanoutyunneru [The Massacres of the Province of Dikranagerd and the Atrocities of the Kurds], Cairo, Krikor Djihanian Press, 1919, p. 95.

- [92] Hamarod Deghegakir Dikranagerdi Verchin Godoradzneroun (Badgerazart) [Overview of the Last Massacres of Dikranagerd (Illustrated)], Dikranagerd Compatriotic Union, 1919, p. 25.

- [93] “Vidjag Azk. Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi.”

- [94] Ibid.; S. M. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [The Western Armenian World], New York, 1947, p. 746.

- [95] Armenia Newspaper, 6 January 1886, number 42.

- [96] Vidjagatsouyts Kavaragan Azkayin Varjaranats…, p. 17. For the classification of grade levels, see Pelag, “Antranig Shrchanavardneru Diyarbekiri Varjaranen.”

- [97] Vidjagatsouyts Kavaragan Azkayin Varjaranats Tourkyo, p. 17.

- [98] Garo Sassouni, “Horizone Horizon” [“From Horizon to Horizon”], Pakin Literary and Artistic Monthly, year 12, number 9, Beirut, 1973, pp. 15-16. Also, A. Nersisian, Garo Sassouni, Yerevan, Caucasian Center for Iranian Studies, 2004, p. 28.

- [99] “Vidjag Azk. Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi.”

- [100] Armenia Newspaper, 6 January 1886, number 42.

- [101] Papazian, “Grtagan Kordzu Dikranagerdi Mech.” Also, Debaghian, “Tovmas B. Zavzavatdjian,” p.7. In 1888, the board of trustees of the Saint Sarkis School resigned and the school was closed, pending the board’s re-appointment. After this, Zavzavatdjian retired from teaching and took up his former occupations again, working as a weaver and engraver. The gradually intensifying persecution he suffered at the hands of the Hamidian authorities forced him to flee Diyarbekir in the early 1890s. He emigrated to the United States (ibid., p. 8).

- [102] Ibid.

- [103] Sassouni, “Horizone Horizon,” pp. 15-16; Nersisian, Garo Sassouni, p. 28.

- [104] “Vidjag Azk. Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi.”

- [105] Ibid.

- [106] Armenia Newspaper, 6 January 1886, number 42.

- [107] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 161.

- [108] Boghosian, Badmoutyun Hay Mshagoutayin…, p. 446.

- [109] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 161.

- [110] “Vidjag Azk. Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi.”

- [111] Armenia Newspaper, 6 January 1886, number 42.

- [112] “Vidjag Azk. Varjaranats yev Ungeroutyants Dikranagerdi.”

- [113] Mgount, Amidayi Atsakanker, p. 161.

- [114] G. B. Adanalian, Houshartsan Hay Avedaranaganats yev Avedaranagan Yegeghetsvo (Knnagan Dzanotoutyunnerov) [Memorial to Armenian Evangelicals and the Armenian Evangelical Church (with Critical Commentary)], Fresno, 1952, p. 471; Rufus Anderson, History of the Missions of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, to the Oriental Churches, volume 2, Boston, Congregational Pub. Society, 1872, p.83.

- [115] Ibid, p. 227.

- [116] Cuinet, La Turquie D’Asie, p. 455.

- [117] Adanalian, Houshartsan Hay Avedaranaganats…, p. 473.

- [118] M. B., “Artsakank Diyarbekiren. Varjarannerou Vertapatsoumu” [“Echo from Diyarbekir: The Reopening of Schools”], Arevelk Newspaper, Constantinople, 26 September/9 October 1903, number 5370.

- [119] Cuinet, La Turquie D’Asie, p. 455.

- [120] M. B., “Artsakank Diyarbekiren…,” Arevelk Newspaper, number 5370.