Diyarbekir – Family and Religious Customs and Traditions

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 23/07/20 (Last modified 23/07/20) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Lifestyle of Diyarbekir Armenians

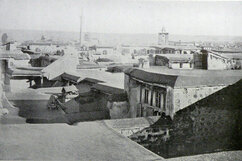

The Armenian population of Diyarbekir/Dikranagerd on the eve of the Armenian Genocide was approximately 35,000-40,000. They lived alongside a diverse array of other national and religious groups. The unique Armenian dialect of Diyarbekir was the dominant language among the city’s Christians [1]. The Armenians of the city included renowned merchants and master craftsmen. Among the crafts they practiced were blacksmithing, pewter making, construction, cobblery, carpentry, masonry, jewelry, tailoring, saddlery, weaving, etc.

Many of the city’s Armenian families owned gardens and orchards.

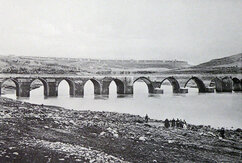

The Armenians of Diyarbekir lived an opulent and cheerful lifestyle. Around them, nature’s bounty was abundant, and the climate was temperate. Whether they were poor or rich, whether they had small or large incomes, enthusiasm for life and hospitality were dominant traits of their temperament. They always found opportunities for celebrations and feasts. Among these were betrothals, week-long weddings, the pesabadiv (when in-laws invited a newly married groom for a visit), the nerabadiv (when a newly married groom invited his in-laws for a visit), other gatherings organized in honor of in-laws, births and baptisms, name days, church and national holidays, pilgrimages, etc. The walls of the city had four gates, immediately outside of which were expansive and beautiful orchards. These were popular destinations in the evenings. Families would visit them dressed in their best attire and bedecked with their best jewelry and trinkets. Similarly, feasts and excursions were organized along the banks of the Tigris River [2].

Celebrations

When holding celebrations, the Armenians of Diyarbekir would invite neighbors, in-laws, acquaintances, and friends. According to tradition, male and female guests were seated separately, at separate tables. It was not necessary to wait for a special occasion to hold a celebration. The aim was simply to meet with friends, chat, share a meal, and enjoy each other’s company. Such gatherings were usually held during the winter when the weather forced people indoors.

During celebrations, women would play the daf, santour, and masha (an instrument similar to the old bambir). Men would play the keman (violin), qanun, dmbek, and chghartman (a flute-like instrument with seven holes) [3].

Beginning in March, when the violets began to bloom and the migratory birds returned, families would begin working in their fields, located beyond the city walls. In April, they would organize excursions to the almond orchards. In May, they would visit the rose gardens, among which was the famous Geoturmaz garden. In June, they would visit the Alipounar and Keterbel gardens. In the summer months, during harvest time, many would temporarily relocate to the bostennire (the vineyards and the fields of melons and watermelons), on the banks of the Tigris. There, each family would have already built a houlle (hut). After spending their days engaged in backbreaking work, upon sunset, they would visit each other, set tables, hire musicians, and organize festivities. The most sought-after dish in the fields was pacha.

Another fascinating custom was practiced when the people were out in the fields. At night, on the banks of the river, families would send lamps to each other by floating them down the current. They would scoop out watermelons, fill the shell with ash, rags, and kindling, then pour kerosene over the flammable material and light it. They would then push these makeshift rafts down the river. This would lead to a beautiful procession of torches floating down the Tigris, each raft welcomed with cheers and applause [4].

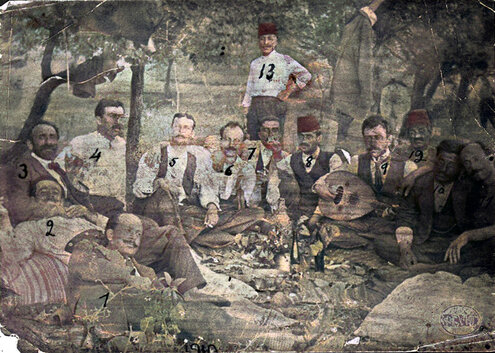

1) Armenians picnicking in Diyarbekir, 1910 (Source: PROJECT SAVE, Armenian Photograph Archives, Watertown, MA, courtesy of John Kazanjian).

2) Armenians in Diyarbekir, c. 1912, photographer unknown. Ready for merriment with a kanoun, a violin, a waterpipe and a bottle of arak. (Source: Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, Watertown, MA, courtesy of Antranig Tarzian).

These photographs, originally in black and white, were digitally colorized using DeOldify and were retouched by Houshamadyan. Scroll to the end of the article for the original photographs.

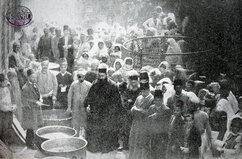

Churchgoing

The Armenian community of Diyarbekir was concentrated in the neighborhoods surrounding Armenian churches. The two Armenian Apostolic churches in the city were the Saint Giragos and Saint Sarkis. The Evangelical and Catholic Armenian communities also had their churches. Every Sunday, after services, the meat of slaughtered cattle would be distributed to the public. This compassionate custom had a long history in Diyarbekir. The meat was prepared in several large vats called jamu bghints, then distributed to the poor in pails. The food was even delivered to the home of the sick, destitute, and downtrodden. On holidays and on special occasions, the wealthy would make donations to sponsor the distribution of food [5].

The city also had its poorhouse, to which Armenians donated generously, both on holidays and on other occasions. Donations were made when people recovered from diseases, in the memory of the deceased, when people were rescued from hardship, when people returned from abroad, etc. [6]

Pilgrimages also played an important role in the life of Diyarbekir Armenians. On every major holiday, people would pack carts with the necessities, and alongside their families, would travel to visit the monasteries or holy sites in the area. The elderly and the children would ride in the carts, while the young would walk along. These pilgrimages often devolved into communal celebrations. The city’s Armenians also made a habit of visiting the Holy Land. They would save money all year to make the pilgrimage and earn the title of hedji mahdesi. Pilgrims returning from Jerusalem were welcomed back with great pomp and celebratory feasts. Their acquaintances would kiss their hands as a sign of their reverence. In their turn, returning pilgrims would gift their friends and loved ones armaghans (souvenirs) brought from the Holy Land.

Family Life

The homes of the city’s Armenians usually consisted of two floors. The exterior was not particularly attractive, but within the walls, they were comfortable and elegant. The courtyards often featured pools and were decorated with large vases. Each home had its tonir house, which also served as the kitchen. Each household’s wealth was measured by the size of its kiler (storeroom), as well as the size of the jugs and the amount of food stored in it. Each family endeavored to have a storeroom overflowing with jugs full of supplies. The people would wish each other “Hayr Eprehemi khern ou berekete beges cheghne geresnerin” [“May your jugs never be deprived of Father Abraham’s blessings.”] The grandmothers would place the Eucharist they received at church in these jugs, hoping that it would bestow its blessings on the home and all who lived in it [7].

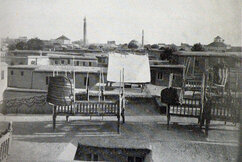

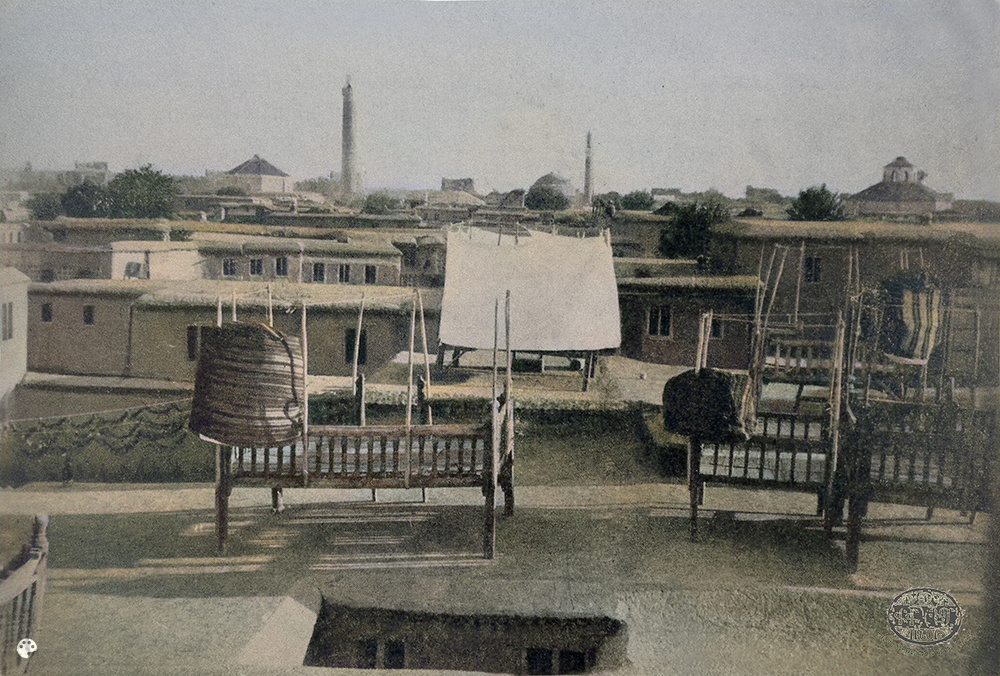

The roofs of the houses were generally flat. In the early summer, families would set up their takhds, or large wooden beds, on the roofs. Curtains, in the form of sheets, would be drawn across the frames for privacy. In some places, these beds were called chardakhs. A jug of water was kept at one end of each bed. In the evening, the water was sprinkled, and when the wind blew down the mountains, the household went up to the roof, and in the cool air of the winter, an entirely different life began for them. They would share meals and go from takhd to takhd, visiting each other. The elderly would recite folk tales, the girls would sing, the children would play, and the women would whisper the latest news to each other until late into the night, when peace would eventually descend [8].

It was common in Diyarbekir for neighbors to help each other. Mgrdich Margosian, in his autobiographical work Mer Ayt Goghmere [Those Parts of Ours], describes how households helped each other prepare for winter: sheghre gdril (cutting vermicelli), cleaning coal, winnowing and boiling wheat, preparing dough and bulgur, etc.

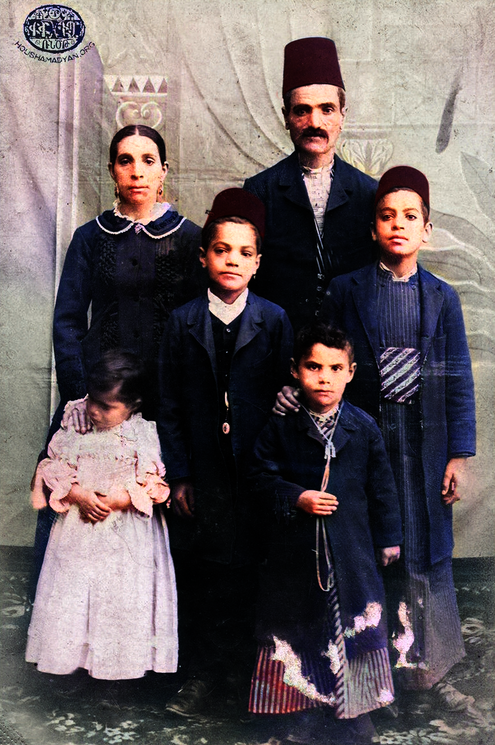

1) Diyarbekir, the Asfar family. In the back row: Sara Asfar and her husband Krikor Asfar with four of their children. The family belonged to the Assyrian community of Diyarbekir (Source: Christine Asfar George collection, Johnstown, Pennsylvania).

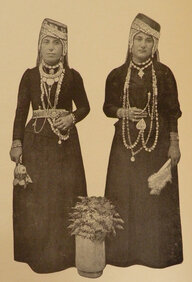

2) Names of women and children unknown, Diyarbekir, pre-1915; photographer unknown. Armenian women wear seed-pearl headdresses with earflaps, unique to Diyarbekir (Source: PROJECT SAVE, Armenian Photograph Archives, Courtesy of the Boyajian Family, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, through the kindness of Bishop Papken Varjabedian).

These photographs, originally in black and white, were digitally colorized using DeOldify and were retouched by Houshamadyan. Scroll to the end of the article for the original photographs.

Margosian remembers that although some families had dining tables, it was more common to eat meals sitting on straw mats on the floor and out of a copper brgich (sini, tray). The lady of the house would serve the main dish in the large tray, alongside cheese and bread, herbs, and seasonal vegetables. The family would gather around the meal, say the Lord’s Prayer, and would eat using their wooden spoons, helping themselves from the communal dish [9].

The Armenians of Diyarbekir were of a straightforward and simple nature. It was a daily occurrent to go musafer (visit someone). In the chapter entitled “We Went to See the Bozoyents” of his book, Margosian describes a night visit to the home of the Bozoyents family. Apparently, there was no need to give prior notice when visiting. Simply, after dinner, families would pick up a kmbo (small kerosene lamp) to light their way and walk together to their destination. They would knock on the door using the chakhchakhos (door knockers). If their friends were at home, the door would be opened. If not, it meant that they were visiting someone else. In this case, the family would choose another home to visit. “We came as musafers to you,” they would say, take off their shoes, and walk in. Their friends would welcome them happily: “Mir klkhin vre, egek egek, ners mdik!” [“Welcome, welcome, come on, come inside!”].

The men would often play dama (Turkish checkers) and drink wine, while the women would knit and exchange news. The elderly, after telling fairy tales to the young, would doze off, huddled together in front of the fireplace. The children would crack walnuts on the floor, then wrap the nuts in bastegh (grape leather) and eat while playing [10].

There were several old and large public baths in Diyarbekir, and visiting these baths was an important part of life for the city’s residents. The baths were built near the river, and thus enjoyed an abundant supply of water. The wealthy permanently rented djourous in this area. Djourou is usually translated as canal, but in this case, it denotes a pool. The women of the city would send porters ahead to the baths with their legens (tubs), tsak-legens (little tubs), and kildans (boxes containing soap, luffas, and combs). Then, with great ceremony, all the women and children of the family would ride a carriage to the bath, taking with them food, sweets, and juices. Naturally, the baths were conducive to women choosing brides for their sons. They would thoroughly scrutinize the young girls while other women provided advice or communicated this-or-that candidate’s flaws with furtive glances. The men’s baths were in different buildings, and unlike the women’s baths, were open at all times of the day [11].

Especially in the city, it was customary for both boys and girls to attend school carrying their defters (exercise books) and kelims (pencils). After returning home from classes, girls would help their mothers with domestic work – cleaning, sewing and mending, weaving, cooking, and embroidering. The teenage boys, meanwhile, would enter into apprenticeships with craftsmen, and would also help run errands outside the house. On Sundays, many of them would go to church and serve as tbirs (acolytes).

Margosian remembers that the typical age of marriage for girls was 14-16, and for boys 18-19. If a girl was 18 years old and still unmarried, she was deemed to have “stayed at home.” If a boy turned 20 and was still unmarried, he was “either drunk or crazy.” If either a man or woman was 40 years old and did not yet have grandchildren, it was concluded that he or she had “never seen the light of the sun.” [12]

Margosian, reminiscing about the first time he fell in love, mentions several customs practiced by teenagers to find spouses. The young men would stand outside the baths, waiting for the young girls to come out so they could see them and make their choices. As for the girls, when bringing water back from the spring, they would “accidentally” spill it on the boy they liked, or would drop their handkerchief out of the window when he walked down the street. The boy would share the secret with his mother, and upon her approval, would respond to the gesture [13].

Toiletry items from Diyarbekir, part of the Silva Özyerli Collection (Istanbul). From left to right: a bathrobe/bath gown (fouta), a copper soap case (kildan), a boroda (a white cloth that was spread on the floor after baths, and on which people sat and enjoyed dried fruits), and wooden bath sandals (nalens).

Aghchigdes (Visiting a Potential Bride)

Selecting a bride for a young man was the duty of his mother and sister. Customarily, a candidate would be invited as a purported konakh (guest) to the house, alongside other girls from among the relations. The guests would sometimes be kept for several days, affording the family the time to get to know the potential bride. Another custom was for the mother of a young man to attend church services, and afterwards, speak to her female friends, asking them to “aghchig me saluzen,” or to find a suitable bride for her son. The mother and her relations would then visit any plausible candidates. This visit was called the aghchigdes.

There was no need to agree on the visit in advance. The guests simply struck the chakhchakho (door knocker) several times softly and in quick succession. This meant that they were there on an aghchigdes visit. One of the household’s adults would open the door, while the girl retired to get ready before meeting the guests. While the women chatted, she would serve coffee, which would give the guests the chance to scrutinize her – her stature, her face, her demeanor, etc. If they approved of her, they would visit again the following week, and this time, they would state to the bride’s mother: “With the will of God, we would like your daughter’s hand for our son.” The girl’s mother would first demur and make a pretense of refusing, in order to preserve the honor and reputation of her daughter. This would also give the girl’s family the time to inquire about the potential groom – who he was, what kind of temperament he had, what prospects he had for a livelihood, his position in society, etc. Once the two sides were satisfied with their inquiries, they entered negotiations [14].

Khosgarnoum (Asking for the Bride’s Hand)

The groom’s father and relatives, having first notified the bride’s family, would call upon them on a Sunday evening, accompanied by the parish priest. Women would not be in attendance. The men would chat for a while, then the priest would deliver a religious sermon on marriage, announce that they were there to ask for the bride’s hand, and conclude with the words: “With the will of God, we have come to ask for your daughter’s hand in marriage.” Naturally, the bride’s family would demur and raise objections, passing around the responsibility of making the final decision. Finally, the girl’s uncle would declare: “I am in agreement if her father also agrees.” This would bring the negotiations to an end. The men would proceed to celebration, raising their glasses in toasts and congratulations. This being an official event, musicians would not be present [15].

Betrothal

The following Sunday would be designated as the day of betrothal. The prospective groom’s family would go the church and have the priest bless the betrothal nshan. This nshan would usually consist of several items, depending on the means of the prospective groom’s father. It would always include a ring, a watch, and several items of gold jewelry. The prospective bride’s family would be gathered at her home, ready to accept the nshan. They would also host a small reception on this occasion.

The prospective bride’s family chose the date of the wedding. This would afford them the time necessary to prepare her dowry. During the betrothal period, especially on church holidays, the prospective groom’s mother, alongside other female relatives, would visit the bride-to-be, bringing gifts and sweets with her. To preserve modesty, the groom-to-be would have to avoid the environs of the bride’s home for the duration of the betrothal.

Marriage

A week before the wedding, individual invitations would be sent to guests from both families.

On the Thursday before the wedding, all the female guests, including the children, would gather in the bride’s home. There would be singing and dancing, jokes, and the bride’s hand would be painted with henna. A candle would be lit, the henna mixed with water and brandy, then applied to the bride’s palms as she danced.

That same night, the men would take the groom to the baths and would celebrate all night.

Friday and Saturday were reserved for cooking the wedding meals. The bread and cheoreg would be baked, and the cheese and a confection called shakarish would be prepared.

On Saturday, to herald the impending wedding, the groom would send the khalaf to the bride. This would consist of an expensive coat and gold jewelry, alongside a large array of confections.

The wedding would be held on Sunday. Men and women would gather in separate rooms in the bride’s family’s home. The women would dress the arous with songs and dancing, blessing each item of her attire in turn – the veil, the belt, the shoes… Meanwhile, the men would sing: “Yegan danoghnir, charchar groghnir, hoki hanoghnir, eghna shnofour.” [17]

In the groom’s home, his family and friends would be gathered to get him ready. First, his peers of the same age would take him to the storeroom to dress him in his underwear. Then he would be taken to the guest room, where the men would sing humorous songs while dressing him in the rest of his attire.

Both families would celebrate lavishly with food and drinks, music, dancing, and fireworks. This would stretch on until the wedding ceremony, which would usually be held at midnight.

The acolytes would greet the groom and bride with hymns. The priest would officiate the ceremony, receiving a monetary gift as compensation.

After the ceremony, the wedding procession, consisting of a large crowd, would make its way home. It would be led by two youth carrying torches, lighting the way for the musicians walking between them. Behind them, on horseback, would come the Godfather and the bride and groom, surrounded by a crowd of revelers. The young men would occasionally set off rockets into the sky. Customarily, any relatives or friends whose house the procession passed would have a table laid out for them on the street. The candle-lit table would have incense burning in the center, surrounded by various types of drinks, roasted almonds and nuts, sweets, and other delicacies. The procession would pause, the music would become livelier, and the guests would perform a circle dance. The man of the house would serve drinks while his wife sprayed the couple with rose water, congratulating them: “May God keep you, may he save you from the evil eye, may you grow together and bear fruit!” [18]

A lavish table would be laid out in the guest room of the groom’s home. The main dishes would be roasted chicken and pilaf. The music would go on until the morning.

The following day, the priest would visit the home to “bring the wedding to an end.” Until then, the bride would still be with the women, and the groom with the men. They would now stand side-by-side in the courtyard, and the priest would pray over them. At the conclusion of this prayer, an elderly woman would sprinkle them with rose water, then spin the censer around them while chanting “Asdvadz shnofour ene” (“May God Bless you”) [19].

Dowry

The bride’s djhez (dowry) would be carried out of her family’s home by porters. One porter would carry the trunk containing the dowry, the other would carry the bride’s basin and toiletries. The items of the dowry would be showcased with great ceremony in the groom’s home, in the presence of the women.

It was customary for dowries to include at least a few dzandr tserks, beautiful gowns sewn with silver thread, alongside the srmaye kourks, which were coats that matched the gowns. The dowries would also include sazos (short coats); zbouns (underwear) of various thickness and made with various fabrics; Baghdadou shals (Baghdad scarves) with blue floral prints; peshdmals (aprons) for various types of usage and of various patterns; Lahore djars (a type of belt sewn with Indian fabric); tezniks (sleeves); srdanots (brassieres); Istanbolya chite mandils (handkerchiefs); kolans (stockings); etc. Footwear was kept in special sacks. This included shoes for both daily use and for special occasions: kalosh potins, teghin djezmas, shoes with toes worked with golden thread, ornamental slippers, etc. Women used red veils to cover their faces when necessary. The dowry would also include towels of various shapes and sizes for the body and the hair; bath gowns; as well as basins, tubs, wooden chairs, combs, luffas, bath towels, etc.

All of this would be carried in a special trunk, built of walnut wood. Other dowry items included the badan eynasi, a large mirror that would be hung from a wall, as well as a small hand mirror to carry in the purse. Notably, for brides who were literate, the dowry would always include a copy of the Bible in modern Armenian, with a wonderful locking binding and gilded corners. There would always be a peshtaghta, a small wooden box that contained jewelry. Women had an astounding array of jewelry items: djagdnots, pearl chits, pearl pskuls (fringes), pearl fezzes, gold-threaded puskuls, etc… As for daily use, they had the bochir (hair band), and for special occasions, a hair band with gems. They would also have one to ten karpouzes or btirs (bracelets), btoum oghir (earrings), watch chains, geardanlez (pendants), sharans, gold fish trinkets, blazougs, khalkhals, etc. There were many types of rings. Aside from the usual, the women of Diyarbekir wore a large ring on their thumbs, called zike, as well as the takhem, a set of eight rings with variegated gems that were all worn together. Children wore msases (bracelets) or zeng zengs (ankle bracelets). Blue beads, called mavi peroz, were worn to ward off the evil eye [20].

Anerbadiv (Honoring the In-laws)

The Sunday following the wedding was reserved for the anerbadiv. The parents of the groom would organize a lavish celebration in honor of the bride’s father, as a token of their gratitude. On that day, the bride’s father and other relations would visit their daughter for the first time since the wedding. A special ceremony would be organized to mark this event. Tea would be served to all the guests, and the father of the bride, as well as any of the other guests wishing to do so, would place gold ornaments inside the teacups upon returning them. The festivities would continue late into the night.

On the following Sunday, it was the turn of the groom to be honored. This was called the pesabadiv. The groom and his relatives would visit his in-laws’ home. This was yet another opportunity to organize a celebration.

Later, the bride’s mother, alongside other female relatives, would visit her daughter. This would be followed by the groom’s mother visiting the bride’s parents [21].

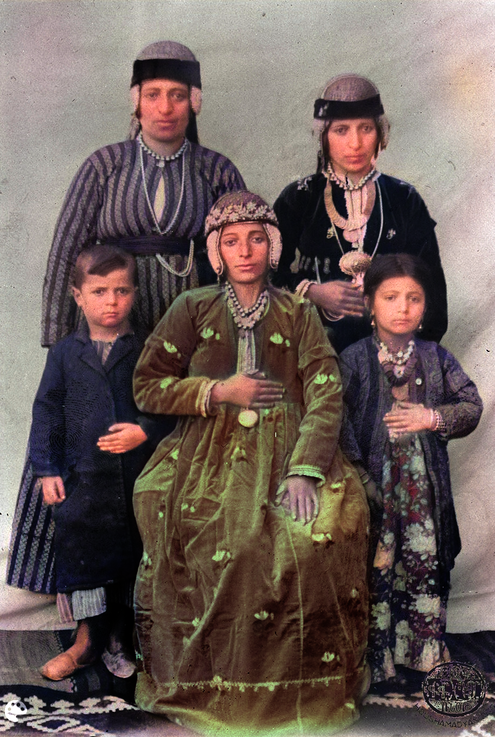

1) Diyarbekir. Carpenter Krikor (or Koro, seated on the left) and his family (Source: Dikran Mgount, Ամիտայի արձագանգներ [Echoes from Amida/Diyarbekir], Vol. 1, New York, 1950).

2) The Proodian Family, Diyarbekir, c. 1912 (Source: PROJECT SAVE, Armenian Photograph Archives, Courtesy of Antranig Tarzian)

3) The Malkhasian/Malkasian Family, Diyarbekir, 1911. Only three of those pictured here survived the Genocide: seated at the center the young boy, Harutiun, the small girl on the right, Toontouch "Florence" Malkasian, and the young woman Arek, standing on the left (Source: PROJECT SAVE, Armenian Photograph Archives, Courtesy of Antranig Tarzian).

These photographs, originally in black and white, were digitally colorized using DeOldify and were retouched by Houshamadyan. Scroll to the end of the article for the original photographs.

Birth and the Dghatskani Paghnik (Postpartum Bath)

Margosian remembers that in Diyarbekir, pregnant women were called dkhmrov(with a dkhmar, or with child), and were attended on by everyone around them, especially during their first pregnancy. The midwife who helped with labor was called kourme mama. She was held in high esteem by the community. When children saw her in the streets, they ran to her and kissed her hand [22].

When the mother’s contractions began, the midwife was summoned. A few elderly women would assist her, fetching warm water, clean rags, etc. “It’s a boy, congratulations!” would herald the midwife. If the child were a boy, she would receive additional compensation. The newborn would be washed, cleaned, and swaddled before being handed to the mother. The mother-in-law’s first task was to cook malez. The mother would remain in bed for a full week.

Once the mother had recovered enough to leave the bed, her female acquaintances would begin visiting her. Then, the mother and infant would be taken to the baths for the dghatskani paghnik. With them, they would take food, chief among which would be the dghatskani halva, made with various herbs and spices. Specifically, it would consist of honey and oil mixed with corn cockle seeds, cloves, mastic, nutmeg, cinnamon, turmeric, anise, coriander, ginger, allspice, black pepper, cardamom, etc. All of this would be kneaded together and rolled into small balls. These balls would then be rolled in sesame seeds, arranged in a box, and taken to the baths. But before eating the halva, the other women would rub it all over the mother’s body. She would then spend several hours inside the baths to allow the ingredients to be absorbed through her pores, thus aiding in her recovery. The women would then proceed to a room where they would make tea and drink it together. The halva would also be sent to relations and acquaintances.

In his memoirs, Margosian also writes that it was customary to lay infants to sleep in a specially built cradle called gadjoren. Two large nails would be hammered into adjacent walls, a rope would be tied between them, and sheets used to make the bed in which the infant lay [24].

Baptism

Like in all other Armenian regions of the Ottoman Empire, infants in Diyarbekir were baptized within 40 days of birth. The baptism ceremony was sometimes held in the church, but also often at home. To celebrate the ceremony, the family would invite guests and serve a dessert called hasa.

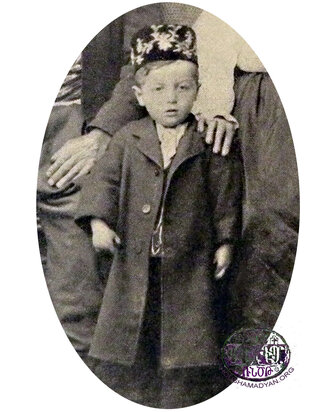

Embroidered headgear for children, part of the Silva Özyerli Collection (Istanbul). The little boy in the center of the photograph (a close-up of another photograph) was a member of the Kasabian family of Diyarbekir. (Source: Dikran Mgount, Ամիտայի արձագանգներ [Echoes from Amida/Diyarbekir], Vol. 1, New York, 1950).

Agra Hadig (Teething Celebration)

When an infant teethed for the first time, the paternal grandmother would invite female in-laws, acquaintances, friends, and neighbors. She would boil wheat alongside a small amount of chickpeas. After draining the boiled cereals, she would mix in various sweet spices, such as cinnamon, anise, aromatic seeds, cloves, etc. Then she would add sweetened leblebi (roasted chickpeas), raisins, walnuts, almonds, etc.

The infant would be seated on a rug, in the center of the room. His or her head and face would be covered by a veil, and then an array of objects would be laid out before him or her, each symbolizing a profession – scissors, a pen, a hammer, a thimble, a ring, a bracelet, etc. Other children would continually sprinkle the infant with grains of wheat while an elderly woman sang Mor Kovasanke [A Song in Praise of Mothers]. The others would watch to see which object the infant picked up. This choice would augur the infant’s future profession. If the infant were a girl, the object would symbolize the profession of her future husband. Thus, if the child picked up the pen, he would be a writer/scholar; if he picked up the thimble, he would be a tailor; if he picked up the ring, he would be a jeweler; if he picked up the hammer, he would be a carpenter; and the bracelet symbolized fine arts and painting [25].

Death and Burial

When a household had an extremely ill or very elderly and bedridden member, the family would place a Bible under his or her bed. Then they would summon the priest for the last rites. News of the death would be broadcast to the public with the pealing of the church bells. Upon hearing it, people across the city would stir and wonder who had passed away. Upon discovering the deceased’s identity, they would rush to his or her home to bid one final farewell, express their condolences to the loved ones, and offer their assistance with the funeral arrangements.

The priest would perform the rites of the funeral and requiem, receiving his compensation in return. Margosian writes that at the conclusion of the funeral ceremony, bread and halva would be distributed to the poor, and then the attendees would leave to attend the hokedjash (meal served after the funeral) [26].

On every Remembrance Day of the Dead (Merelots), believers, especially women, would visit the graves of their loved ones to light incense and pray. They would end their visits with the recitation of the hymn Voghormi Erte Hokernout [27].

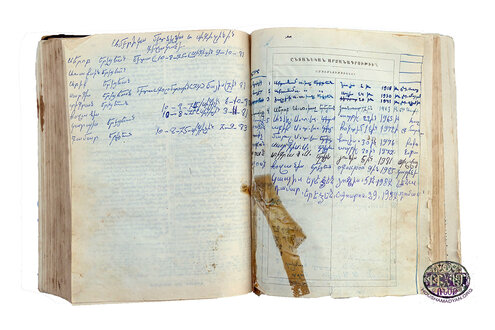

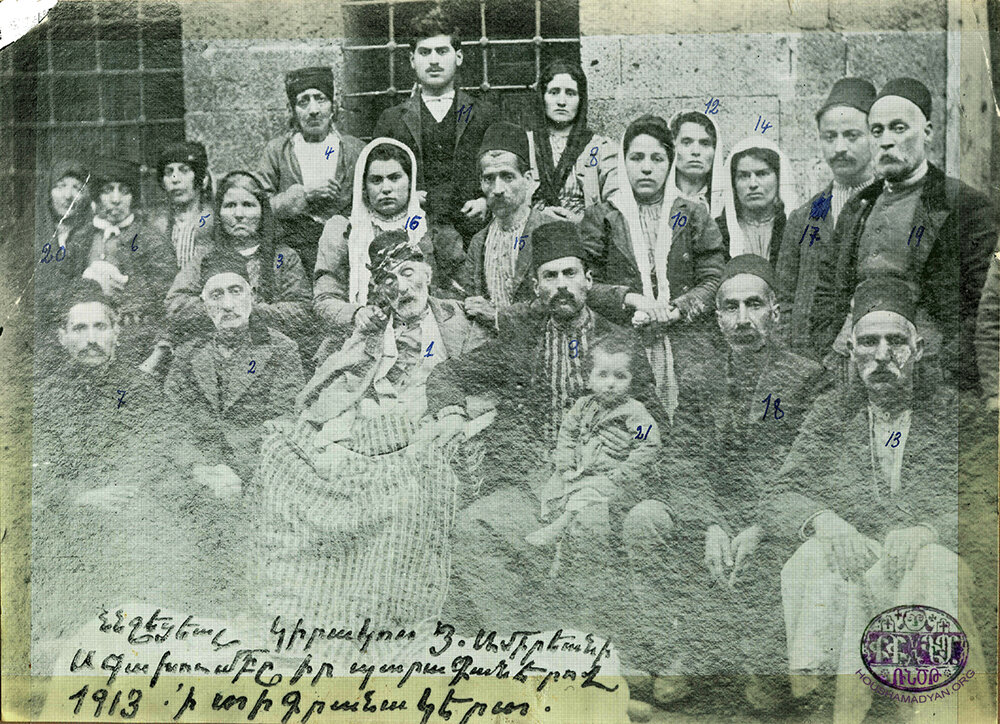

A funeral photograph, Diyarbekir, 1907 or 1908. The deceased is Giragos Amirian (#1), who has been positioned in a chair. #2 is the deceased’s brother, Hagop Amirian. #3 is the deceased’s wife, Proun (Prapion). #4 is the deceased’s sister (name unknown). #5 is the deceased’s sister, Hanum. #6 is the deceased’s sister, Sara. #7 is the deceased’s son, Aslan. #8 is Aslan’s wife, Lucia. #9 is the deceased’s son, Hovsep. #10 is Hovsep’s wife, Sousli. #11 is the deceased’s son, Dikran. #12 is the deceased’s daughter, Gadar. #13 is Gadar’s husband, Mgrdich Yaldjian. #14 is the deceased’s daughter, Touma. #15 is Touma’s husband, Boghos Ghrbadjian, an artist whose works included the carvings in the interior of the Saint Giragos Church. #16 is the deceased’s daughter, Mnoush. #17 is Mnoush’s husband, Tovmas. #18 is the deceased’s cousin (aunt’s son), Tovmas Vosgerichian. #19 is the deceased’s cousin (also aunt’s son), Bedros. #20 is the deceased’s sister (name unknown). #21 is Aslan’s son, Karnig.

The family lived near the Saint Giragos Church. The photograph is presumed to have been taken in the same neighborhood. Hagop, Proun, Aslan, Dikran, Gadar, Mgrdich, Touma, Boghos, Nmoush, Tovmas, and Karnig all died during the Armenian Genocide (source: Hourig Attarian Collection, Montreal).

- [1] Dikris [Tigris] Yearbook, Aleppo Chapter of the Dikranagerd Compatriotic Union, Dikris Press, 1946, Aleppo, p. 29.

- [2] Ibid., page 10.

- [3] Ibid., page 31.

- [4] Ibid., page 33.

- [5] Ibid., page 16.

- [6] Ibid., page 15.

- [7] Mgrdich Margosian, Mer Ayt Goghmere [Those Parts of Ours], Aras Press, Istanbul, 1994, p. 94.

- [8] Dikris Yearbook, p. 35.

- [9] Margosian, Mer Ayt Goghmere, p. 76.

- [10] Ibid., pp. 127-130.

- [11] Dikris Yearbook, p. 36.

- [12] Margosian, Mer Ayt Goghmere, p. 38.

- [13] Ibid., p. 56.

- [14] Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker [Echoes of Amida], Volume A, New York, 1950, p. 400.

- [15] Ibid., p. 401.

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] Ibid., p. 402.

- [18] Dikris Yearbook, p. 12.

- [19] Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker, p. 406.

- [20] Ibid.

- [21] Ibid., p. 408.

- [22] Margosian, Mer Ayt Goghmere, p. 70.

- [23] Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker, p. 460.

- [24] Margosian, Mer Ayt Goghmere, p. 79.

- [25] Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanker, p. 409.

- [26] Margosian, Mer Ayt Goghmere, p. 37.

- [27] Ibid., p. 28