Agn – Religious Customs

Author: Khazhak Drampyan 28/07/2017 (Last modified: 28/07/2017), Translator: Simon Beugekian

The people of Agn/Eğin (present-day Kemaliye) had great reverence for tradition. Their daily, domestic relationships were regulated by rigid rules that had been passed down through the generations, and which every Agntsi knew by heart. By examining these rules, we can make certain conclusions regarding Agntsis’ notions of their rights and duties. For example, the young were expected to respect and obey their elders; but the elders were expected to always love the young, treat them with fairness, and exercise their authority with kindness. Youth who were able to earn the respect and love of their village considered themselves to have earned their elders’ blessing, and looked forward to a life of success and happiness [1].

The typical household in Agn consisted of multiple married couples of the same extended family. But even in this collective setting, there were clear delineations. The entire household dined from the same larder, but each member of each family was entitled to and watched over his or her own possessions. These delineations of property were based on divisions of labor, and had a positive effect on the relationships among the wives of the household.

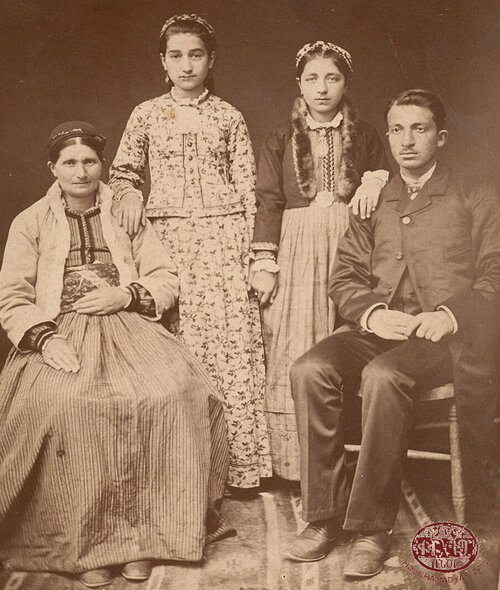

Agn, 1880s. From left to right – Melkon Jamgochian’s mother (name unknown); Akabi Jamgochian (nee Janigian, Avedis Jamgochian’s wife); Margarite Jamgochian (Melkon Jamgochian’s sister, later Kasabian, 1872-1911); Melkon Jamgochian (Avedis and Margarite Jamgochian’s brother, killed during the 1895 Hamidian massacres) (Source: Jamgochian collection, USA).

In Agn, families and relationships between various members of families were anchored on faith. And when the precepts of faith and household regulations merged into one, both young and old endeavored to abide by the resulting collection of conventions, resulting in households where mutual respect, love, and trust reigned [2].

Agntsis were fervently Christian. They trusted God to preserve their families, which, as we have mentioned, were solidly anchored on faith. Prayer and piety were their debt to their Lord. Agntis customarily prayed twice daily, and assiduously observed Lent. They believed it was their duty to always lend a helping hand to their local church and school, as well as to the poor and destitute.

The unique inter-familial relationships and customs of Agntsis also manifested in other aspects of life. Below, we provided some examples, and through these examples we attempt to gain some insight into the character and makeup of Agntsis [3].

Baptism

Infants were baptized approximately 40 days after birth, on a Saturday or a Sunday. The infant would be taken to the church by the Godfather and Godmother in a grand procession. After the baptism and christening ceremonies, the procession would head back to the family’s home, where a celebration would be organized for the guests. Then, in the presence of all members of the family and the guests, the infant would be anointed with holy water. The Godmother would then hand over the infant to his or her paternal grandfather, and the guests would begin congratulating the family with their blessings:

Dnertit shen ou dzaghgadz mna, tornerov ou tornortinerov ltsvi, dzer orerou mech hazar kavazan ounenak!

[May your home remain prosperous and flourish, and may it be filled with grandsons and great-grandsons. May you have a thousand staffs to lean on in your old age!”]

Angoghint kolov, dzenountet bayzar arev tarna, kezi ayt angoghnuyn mech shad desnenk!

[May your bed always remain snug, may your birth become a sun, may we see you in that bed for many long years!] [4]

For the baptismal ceremony, the parents of the infant were sometimes charged a fee by the presiding priest. The fee was proportional to the family’s means. This fee was never charged to the Godfather [5].

The infant’s crib was then filled with packages containing the written congratulations and well wishes of the guests. If the infant was a girl, golden trinkets were placed on her lahore scarf, which would be woven with expensive, valuable thread.

The feast was accompanied by song and dance, and would last late into the night. Three days after the baptism ceremony, a smaller, tighter circle of family members would once again gather to celebrate the washing of the holy water, meaning the bathing of the infant. The remaining holy water would then be discarded at a location that would not be trodden by people [6].

They would place a vat of lukewarm water in the center of the home’s main room. After bathing the infant in water, the wet nurse would place the head of the infant in her left palm, and while rubbing the infant’s forehead with her right hand, she would recite blessings:

Layn djagad ellas, gamar ounkvi ounenas, khoshor achvi, yergayn tartich ellas, pats peran chelas, kich khosis, shad lsogh ounenas, amragour grtski, sona boylu yev jarbig ellas [7].

[May you have a wide forehead; may you have high eyebrows; may your eyes be large, your eyelashes long. May you not have a gaping mouth; may you speak little, but have many listeners. May you have a wide chest; and may you be tall and clever.]

They would then wrap a bundle and roll it onto the ground, having previously placed on the ground a piece of bread, a book, and an inkwell. The significance of this act is illustrated in the associated blessing that was recited:

Khoroung gartatsogh ellas, krchet grag tsadge, Asdzo yergughn ounenas yev hatset trutyamp vasdagis [8].

[May you be a deep reader; may fire spark out of your pen; may you know the fear of God, and may you earn your bread with ease.]

If, however, the infant was a girl, the items consisted of a piece of bread, alongside cotton, gold, and pearls. The blessing was:

Vosginerou yev markridnerou mech loghas, pambagi bes sbidag ou makur mnas, hatset madagararel kidnas [9].

[May you swim in gold and in pearls; may you remain white and unsullied as cotton; may you always know how to obtain your daily bread.]

In Agn, when an infant was taken out of the house to attend his or her baptism, the family crossed the threshold while carrying bread, in order to fend off evil. This bread was then distributed to the poor, in order to earn an additional blessing for the child [10].

If the infant in question was a girl, the mother would knit socks. If the infant in question was a boy, she would read a book of a newspaper, thus hoping to raise a literate son [11].

Agntsis believed that if the person bringing water to the church to be used for the baptismal ceremony looked backwards during his journey, the infant baptized with that water would suffer from a lazy eye [12].

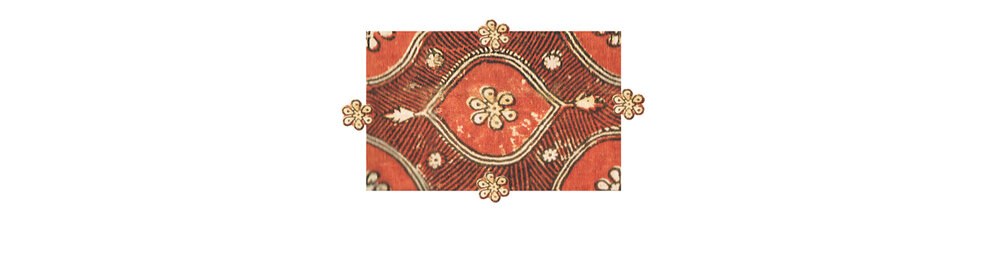

Silver bridal belt, from Agn. The belt once belonged to Almas Kaboulian. After Almas’s death, the belt was passed on to her daughter-in-law Rosa Kaboulian (wife of Kegham Kaboulian), who later brought it with her all the way to the United States. Today, the belt is kept as a family heirloom in the United States (Source: Kaboulian collection, USA).

Khosgab and Betrothal

In Agn, the minimum marriage age for men was 18, and for women, it was 15. By the age of 18, men would already be earning a living. Families would then be in a hurry to marry their sons, on the condition that after their marriage, the sons would replace their fathers or brothers as emigrants in other parts of the country or abroad. Their fathers and brothers would then be able to return home. There was a large number of emigrants leaving Agn with the intention of working elsewhere and earning a living for their families. Thus, early marriages were also a way for the people of Agn to keep their sons, who were often abroad, tied to their native lands, and to prevent their total alienation from the homeland [13].

The job of finding a bride for a young man was reserved to his mother. She would spend years investigating and vetting potential candidates, and would eventually settle on a potential bride worthy of her son. Thereafter, the choice had to be approved by the groom’s father, then the groom, and then the rest of the family. After receiving the approval of the immediate family, the mother would solicit the views of other relatives and family friends. She would also take into consideration the reception she had received when visiting the candidate and her family, as well as the candidate’s character and demeanor, all in an effort to avert a future collapse of the marriage. Finally, at the end of the process, the mother would announce her conclusion to her son, who was usually already aware of what it would be [14].

The groom’s mother was also tasked with the preservation of the family’s honor and moral rectitude. Agntsis were a very righteous people. For them, a family’s name and reputation were all-important, and had to be protected from the danger of being sullied by the actions of children and grandchildren, which reflected negatively on their parents and grandparents. This concern with reputation had a positive effect on children being raised in the city. As boys grew up, they were constantly given the advice and counsel they needed to eventually succeed as family men and in their careers [15].

Once everything had been agreed upon, the khosgab (pledge) ceremony would be scheduled, officiated by a priest. The priest would first speak to both of the families involved, and ensure that both families approved of the union. The ceremony was attended by the couple’s parents and others loved ones. The priest would give the couple his advice, after which he would hand over to the bride’s parents the first gifts of the ceremony, consisting of a ring and jewelry. In response, the groom’s parents would offer gifts of pastries and desserts, in order to share the good news with all who were present [16].

The medz nshantrek (betrothal ceremony) would be held a week or two later. For Agntsis, this was a very important ceremony, associated with very large costs. The ceremony, which had become a way for families to show off their wealth, was particularly important for the bride-to-be’s parents. They would use all of the financial means in their disposal to organize the grandest festivities they could. The groom’s side also attached great importance to this ceremony, and strived to secure impressive gifts for the bride-to-be (usually jewelry). The betrothal ceremony was an opportunity for the families and loved ones of the soon-to-be bride and groom to become better acquainted, and to discuss the details of the upcoming wedding [17].

Details from above presented silver bridal belt from Agn. The belt was made in Van, and sports two maker’s marks, one being the image of a lion, which means the belt was the work of master craftsman Arslanian, and the engraved letters “G” and “T,” which attest to the fact that a second craftsman also worked on it. The name Almas is also engraved on the surface of the belt, as well as the number 98. It is plausible that the belt was made in 1898 (we thank Osep Tokat for providing information related to the belt’s provenance) (Source: Kaboulian collection, USA)

On the day of the betrothal ceremony, the sending of food, drink, and other gifts to the homes of in-laws and friends was forbidden [18].

One of the most important ceremonies during the betrothal celebrations was the khalwat (khalwat means hidden or secret, but in this case it is the name given to the part of the ceremony when the bride-to-be and groom-to-be met in private for the first time, and for a short time). The betrothed couple would go into a room together and speak privately. Two young men from each of the bridal parties accompanied the groom-to-be to his betrothed’s room. The young couple then parted from each other in full view of their families and loved ones. The groom-to-be would give the bride a special gift (a silver box or golden jewelry), while the bride’s party would offer the groom a tray full of sweets, as well as other items [19].

In the Abuchekh Village of Agn, it was customary for the gnkahayr (male wedding sponsor) to pick only one of the family’s friends for participation, alongside himself and the groom-to-be, in the betrothal ceremony [20].

The gold gifted during these ceremonies was usually valued at 20, 60, or 80 kuruş (Ottoman currency) [21].

Family friends were forbidden from gifting the bride-to-be any gold or other presents. For this reason, family friends could not participate in the ceremony of visiting the bride. Additionally, the groom-to-be, prior to being officially betrothed, was forbidden from sending any gifts to the bride-to-be [22].

1. Agn, circa 1885: Wedding portrait of Nicolas and Makrouhy Derghazarian Gabrielian. Photo by A. F. Gabrielian (Source: PROJECT SAVE, Armenian Photograph Archives, Watertown, MA, courtesey of Syranoush Movsesian).

2. Agn, circa 1897: Makrouhy Gabrielian (née Der Ghazarian) and Nicolas Gabrielian with their children. Their last photograph in Agn; the family emigrated soon after to the USA, probably to New Jersey (Source: PROJECT SAVE, Armenian Photograph Archives, Watertown, MA, courtesey of Syranoush Movsesian).

Wedding Ceremony

The wedding ceremony took place two weeks after the betrothal ceremony. During that two-week period, the betrothed couple strove to become better acquainted with each other, while leaving the task of organizing the wedding ceremony to their parents and families. On each Saturday, and on all holidays during that period, the groom, alongside his friends, would visit the bride’s home, where he would be welcomed warmly by the bride’s family. The goal of these meetings was to ensure that the two had time to familiarize themselves with each other, so that they could then make their grand [marital] pledges with full awareness and conviction [23].

After frenetic preparations and much hard work, the family’s parish priest was finally invited to visit the betrothed couple. The priest, equipped with the official marriage certificate, would visit the groom and the bride separately a few days before the scheduled ceremony, and inform them of the date, time, and other details of the ceremony. These visits were dubbed imats devek (notification). In the last week prior to the wedding, messengers sent by the families would go from home to home, inviting family and friends to the bride’s home. The guests would begin arriving on Saturday evening, bringing gifts with them (sheep, baskets, trays of sweets, etc). The guests were accompanied by, and greeted by, musicians [24]. According to custom, the father of the groom informed the father of the bride of the exact time of the ceremony two days prior to the ceremony [25].

Wedding ceremonies in Agn were much more festive and exuberant than wedding ceremonies in the Armenian countryside. The ceremony was governed from beginning to end by clear and unambiguous regulations. These regulations were a reflection of traditional Armenian customs and observances, as well as ancient pagan rituals mixed with contemporary Christian practices [26].

After the arrival of the families and loved ones, and after the first reception and feast, the ceremony known as khnamiyert (visit of the in-laws) was conducted at midnight. One man and one woman were selected from the groom’s party, and were tasked with bringing red henna, which symbolized the marriage, to the bride’s home. The ceremony of decorating the bride with the henna ink was accompanied by music and dancing. The “Henna Dance” was performed by the wedding sponsors while holding an elegant crystal tray. The tray would have several candles burning in the center, and would also hold the henna ink. While the sponsors danced, women gathered around them and sang:

As hinan an hinan che,

Ghrgoghn al inch aghvor manch e. [27]

[This henna isn’t just any henna,

And it was sent by a wonderful boy.]

Then, the bride would approach a cushion placed in the middle of the room. The henna ceremony would then begin in earnest, accompanied by more songs:

Vosgi amani mech hinan shaghvetsin,

Artsat sandrov khobobs kagetsin… [28]

[They kneaded the henna in a golden plate,

They brushed my curls with a silver comb…]

These songs were meant to stir nostalgia in the bride, who was about to bid farewell to her simple, maidenly lifestyle and to her family’s home [29].

The gnkamayr (female wedding sponsor) would then cover the bride’s hands with embroidered gauze and pain them with henna. The young women of the bridal party would brush the bride’s hair and style it, decorating it with golden ribbons. The bride’s head would then be covered with a silk, gold-threaded veil. This ceremony of readying the bride for the wedding ceremony was called kogh tskel (the ceremony of veiling) [30].

This ceremony was immediately followed by the singing of love songs and by dancing. One of the popular dance tunes was the tevbar, during which the dancers would play humorous games and swap partners in such a way that at the end, the groom and bride were left facing each other [31].

During these songs and dances, and in general, during the ceremonial interactions of the couple, their loved ones were not allowed to gift them any gold [32].

After these ceremonies, the celebrants would return to the groom’s home, where he and his friends would also be decorated with henna [33].

The festivities would last until noon on the following day. At that point, the first meal of the celebrations would be laid out. The officiating priest would partake in this meal, during which he would conduct the ceremony known as halav orhnek. The ceremony required the participation of barbers, who would cut the hair of the groom and his friends, and then guide them to their room. There, the groom would don his wedding suit, with the exception of his doublet and coat. Instead, he would wear a fur over his shoulders. His doublet and coat, alongside his hat and the gnkahayr’s sword, would be placed in a tray in front of the priest. Those present would then be invited to hear God’s words. The priest would bless the sword, which would have a white handkerchief tied to the hilt. He would then hand over the handkerchief to the gnkahayr. The priest would also bless the groom’s items of clothing, which he would then hand over to the groom’s brother. The latter, after spinning the clothes in a circle three times above the head of the groom, would dress the groom while reciting [34]:

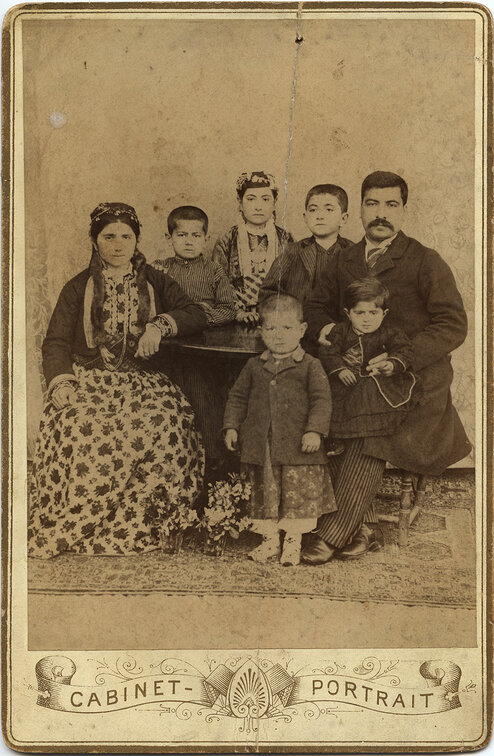

This family most probably hailed from Agn, and the photograph was taken very likely in Agn or a nearby city. The family is unidentified, but the photograph is in the Jamgochian family (from Agn) collection. Therefore, it is presumed that the family in the photograph was either related or friendly with the Jamgochians (Source: Jamgochian collection, USA).

Asdvadz shnorhavor ene,

Asdvadz shnorhavor ene,

Shnorhavorn Asdvadz ene… [35]

[May God bless you,

May God bless you,

May God be the one to bless you…]

Once he had his hat on, the groom was addressed by the title of takvor (king). Whenever he sat, those around him would place cushions on his chairs, so that he would always stand out among those present. And whenever the takvor drank wine, those present had to applaud wish such intensity that the windows and the glasses had to vibrate [36].

Songs of praise sung during wedding ceremonies were customarily dedicated to the bride, but there was one song of praise dedicated to grooms, specifically singing the praises of their physical characteristics:

Yeli gayne, takvor aghpar!

Yes kez kovim, kloukhn i var.

Erech yes kou boyigt esim,

Our chineri dzar gu mani.

Angits yes kou yeresn esim,

Our lousni tal gou mani.

Angits yes kou perchemn esim,

Gulebudun tel gou mani.

Angits yes kou achvin esim,

Our shaheni achk gou mani. [37]

[Stand up, takvor brother,

And let me praise you, from head to foot.

First, I will praise your stature,

You’re as tall as a sycamore tree.

Then I will praise your visage,

Which is like the moon’s halo.

Then I will praise your hair,

Hanging down like beautiful thread.

Then I will praise your eyes,

Which are hawk’s eyes.]

Eating or drinking was forbidden to the guests while the groom was being dressed [38].

After the conclusion of the halav orhnek ceremony, the groom would approach his parents to receive their final blessings. He would kiss their hands, receive their blessing, and also receive a gift from them. Customarily, this gift was a watch or a wallet full of loose money. This gift symbolized the fact that the groom now had the prerogative to carry a wallet, meaning he was now the head of a household [39].

After the halav orhnek, the groom and the gnkahayr had to remain in each other’s company at all times. The other guests, meanwhile, would try to make them the butt of their mischief, by trying to steal the gnkahayr’s dagger or the bride [40].

The halav orhnek was followed by the official visits of the groom’s parents to their new daughter-in-law’s home. As opposed to the hinatrek, the in-laws would be accompanied by a larger group of relatives and loved ones. For this reason, this ceremony was called the medz khnami yert (the in-laws’ great visit). Almost all of the guests in the groom’s party would participate in this visit. The procession would usually be headed by a group of musicians, who would usually play kash harems (heavy melodies).

The bride’s family would greet this procession right outside their home. The objective of the medz khnami yert was for the groom to bring the expensive wedding gown that he had bought to the bride [41]. The bride would then be led to a special room, where the in-laws would be gathered. Upon the bride’s entrance, the in-laws would begin singing:

Aghchig, kou hakadzt al [garmir, keghetsig] e,

Aloug peshert ver dzale.

Kale ou mandrdik kale,

Kou aghdoug boygit yereva. [42]

[Girl, what you’re wearing is [red, pretty] too,

Fold your skirts up.

Prance for us lightly,

Show off your stature, tall as a fence.]

The sister of the bride would then help the bride into the wedding gown provided by the groom, while the musicians continued playing kesh harems. She would then invite the bride to join the other guests [43]. One of the bride’s close relatives, usually the aunt (her mother would not participate in this ceremony, because she would be overcome with emotion), would sit on two cushions placed on top of each other, and would take the bride’s head into her hands, in order to prevent the groom’s family from taking the bride away. Seven women would then try to pull the bride back to her feet, but would fail. Then the gnkamayr, the most respected of the wedding guests, would come forward and successfully raise the bride to her feet. The gnkamayr would then seat the bride on cushions, tie a belt around her waist, and place a hat on her head. Once the hat was placed on her head, the young woman was officially considered a bride. The participants of the ceremony would begin singing [44]:

Yegour, aghvor aghchig, hars yeghar mezi… [45]

[Come, beautiful girl, you’re now our bride…]

One of the most demanding tasks of the bride was the kissing of every guest’s hand. This process would often span hours. The bride, accompanied by her sister, was duty-bound to kneel before each guest, and to slowly and patiently kiss his or her hand. Hours later, once this process was completed, the guests would once again head towards the groom’s home, in order to resume the festivities there. Then, at dawn, they would return to the bride’s home to perform the harsnar ceremony [46].

In the Abuchekh Village of Agn, it was customary for family visiting the in-laws’ home to abstain from all food and drink. They would even abstain from desserts. They were only allowed coffee [47].

The wedding wreaths would be worn by the bride and groom from dawn to dusk. However, they were compelled to preserve their marital fast assiduously, according to regulations [48].

The customary fee paid to the priest officiating a wedding was 20, 30, 40, or 60 kuruş, based on the family’s means. The family also paid an additional fee called a svid hakha (no additional details are available regarding this fee) of 10, 15, 20, or 40 kuruş, based on the family’s means [49].

Harsnar (Escorting the Bride to the Bridal Home)

A harsnar was an inherently beautiful and impressive ceremony. The gnkahayr and gnkamayr, alongside the groom, would lead the procession, mounted on horses. The procession, alongside the accompanying musicians, would make their way to the bride’s home, where they would find the door shut. The bride’s party would then ostensibly create obstacles and demur. The groom and his party would entreat the bride to consent to the marriage with special songs for the occasion [50].

During a harsnar, the groom may not dismount. His companions, also mounted on their horses, must have nothing with them other than their coffee [51].

The groom was soon told by the bride’s party that they did not consent to handing over the girl. Then, the gnkahayr would promise the father of the bride a vat of wine and a table laden with food. Upon this promise, the gates would open, and the groom and his family would enter and go for the bride’s room. Meanwhile, they would continue to sing the praises of the bride’s family and parents. Soon, the bride would implore her mother, through song, for permission to leave the house, and for encouragement to do so:

Mi lar, mayrig! Mi lar! Yes noren di kam,

Asge dasnhink or, erigovs di kam. [52]

[Don’t weep, mother! Don’t weep! I will be back,

In fifteen day’s time, I will be back with my husband]

For the bride’s parents, and especially for her mother, this moment of parting was very difficult. They wondered if their daughter would be happy, and wondered what kind of future awaited her. And so, this moment in the ceremony was usually punctuated by emotional embraces. Then, the doors of the bride’s home would be thrown wide open, and the feast and farewell ceremonies would begin. After receiving her parents’ and her relative’s final blessings, the bride would then join the in-laws’ procession, mounted on a decorated horse. The procession would head directly to the church, where the wedding ceremony would be held [53]. After the ceremony, the procession would accompany the newlyweds to the groom’s home. When he and the bride reached the threshold, the musicians and the women would split up into two groups and begin singing. The first song was addressed to the new bride:

Pari louys! Aghvor! Pari lous! (rpt.)

Pari lousoun parin vrat (rpt.)

Our tsate arevn i vrat. (rpt.) [54]

[Good morning, beautiful, good morning! (rpt.)

The good morning will dawn (rpt.)

So that the sun rises over you. (rpt.)]

They would then address the groom’s mother, imploring her to come out and greet the bride:

Takvori mayr, tours yegou

Takvor vortegt e yeger,

Tek mnatser yev chifa yeghel. [55]

[Mother of the takvor, come outside,

Your son, the takvor, has come,

He was alone, now he’s become a couple.]

They would then address the bride –

Voleretsar, poleretsar

Aghvor! Jampan moleretsar

Moleretsar ou ners yegar

Hay im hay, annman aghvor… [56]

[You wondered, you circled,

Beautiful, you lost your way

You lost your way then came inside,

Hay im hay, unequaled beauty.]

The “lost your way” in the song is a reference to the fact that the bride, after a church ceremony, has made her way to the groom’s home, instead of her father’s home, as she would normally have done [57].

On the following day, after lunch, it was the bride’s turn to visit the groom’s home. The procession would include carts filled with the bride’s dowry, as well as musicians and the multitude of revelers [58].

The bride’s dowry would be taken to the bedroom reserved for the bride in her new home. The boxes would be opened in the presence of girls and women. These women would carefully examine the dowry, evaluate it, praise this or that item, etc [59].

On the following day, in the early morning, the groom and his brother would once again make their way around the village, alongside the musicians, and invite the village to the bride’s home. There, a short feast would be organized, and the revelers would be quenched with wine or arak. This gathering, organized on the day following the wedding, was called pashayi aravod [pasha’s [lord’s] morning], because the fare served was worthy of a pasha’s table [60].

Agn, circa 1892. Seated, left to right – Melkon Jamgochian and Mariam Jamgochian (Melkon’s wife). The children, from left to right – Matteos and Eliza, Avedis (Melkon’s brother) and Akabi Jamgochian’s children. Melkon was killed in Agn during the 1895 Hamidian massacres (Source: Jamgochian collection, USA).

Death and Burial

In Agn, Just like births, baptisms, and wedding ceremonies, various unique customs were associated with deaths and burials [61].

After death, the deceased was kept in the house for one day for the final farewell. After this one-day wake, the body was transferred to the local church. Aside from the natural and universal expressions of grief, Agntsis also had their own unique ways to paying respect to and mourning their dead. Most ceremonies involved the women. Women would get together in a room, where they would compose and sing dirges praising the character and celebrating the life of the deceased. They would embrace the other mourners, and share the household’s grief. The dirges and the grieving would come to a stop with the intervention of the men, as there had been instances of some women losing consciousness, and even dying, after particularly intensive bouts of grief [62].

Beginning in the mid-1800s, as a result of pressure exercised by educated youth, and thanks to the sermons of the clergy, it became possible to rein in some of the excessive expressions of grief and the use of garish dirges in the city. Alongside these reforms, a stop was also put to the custom of three-day funeral meals, which were hosted by the deceased’s household, in the presence of many guests. These three-day meals were associated with many financial difficulties for the families concerned, as due to its geographic location, the residents of Agn could not simply walk to a market or practice commerce whenever they wished. Agntsis had only two opportunities per year – in the autumn and the spring – to accumulate enough food for the entire year [63].

Burial photograph from Agn, circa 1910. The dead child was Boghos and Rebecca Kaboulian’s five-year-old son, Hovhanness. The bearded man seated right behind the coffin is Boghos Kaboulian, and on his left is Rebecca Kaboulian, covering her face with a handkerchief. At the feet of the deceased child is Varsenig (Boghos and Rebecca’s daughter), and the boy standing near the deceased’s head is Gabriel (Boghos and Rebecca’s son) (Source: Kaboulian collection, USA)

On the eight-day anniversary of a love one’s death, as well as on the forty-day anniversary, the one-year anniversary, and on the five days of the year reserved for remembrance of the dead, Agntsis visited the graves of their loved ones. There, they blessed the graves, honored the memory of the deceased, and distributed gifts to the poor. Others preferred requiem ceremonies conducted in churches [64]. The tombs of the deceased were also visited on other holidays [65].

Another custom was the placing of a tombstone on the one-year anniversary of a death, and this was another occasion to remember the deceased [66].

According to ecclesiastic regulations, each church required a specified fee for a burial. This fee ranged from 6 to 200 kuruş. Additional gifts to the officiating priest were also not frowned upon. However, if a family refused to pay the prescribed free, the priest was obligated to take the issue up with the neighborhood council [67].

Ecclesiastic regulations made no stipulations regarding fees for services in the memory of those who died in foreign lands [68].

Dirges

Agntsis had preserved the traditional customs of mourning the dead, and the customary mourning was accompanied by dirges and, in the popular jargon, laments. The family of the deceased composed these dirges, or, more often, borrowed popular dirges which could be altered to suit the occasion [69].

Two rooms were set aside in the home of the deceased, one for the men, and one for the women. If the home was not large enough, the home of one of the neighbors was used for the occasion [70].

The dirges and laments were recited in the room reserved for the women, in the presence of the deceased’s closest female relatives (e.g. mother, sister, daughter, aunt, etc). If the deceased was a particularly prominent and respected individual, the dirges would reflect this fact in their duration and exuberance. The family might also invite some of the city’s famous professional mourners, who would pay appropriate respect to the deceased with their laments and weeping, and share the pain of the family’s loss [71].

Songs called andounis were also popular in Agn. They were short songs celebrating various episodes of the deceased’s life, and also praising the deceased’s virtues. These songs were usually written in formal, old Armenian, and had a rigid structure and rhyming scheme [72]:

Yertam khaj gakvuk lenim,

Kam tarim kou penjireyit

Inchvan ah our zar anim

Fizahes kounet chi dani… [73]

[If I were a hazel partridge,

I would perch on your windowsill,

And I’ll raise such a racket

That my anguish will keep you from sleep.]

As opposed to the andounis, popular dirges were sung in colloquial Armenian and were not so rigidly structured:

Haydi, yertank lernern i ver

Sev ou teghin dzaghig kaghelu

Seve tnenk sev srdnernus,

Teghinn ilan elli,

Khatun mors yarannerun. [74]

[Come, let’s journey up the mountains,

To pick black and yellow flowers,

The black to match our hearts,

And the yellow, for an ointment,

To heal the khatun [dignified title for a lady] mother’s wounds.]

Agntsis had many customs and superstitions surrounding death. Some are described here:

When a member of a family passed away, threads of cotton were measured in the size of the other members of the family, and buried alongside the deceased, with him or her in the burial shroud. The purpose of this act was to bury any diseases that the family members suffered from alongside the deceased [75].

If, after a family member’s burial, a member of his or her family fell ill, a shirt was placed around the deceased’s tombstone, hoping that the disease would remain in the shirt and die out [76].

Agntsis asserted that those who planted walnut trees were condemned to die if the width of the tree’s trunk exceeded the width of their necks [77].

Father Karekin Srvantsdyants’s Decree

On November 3, 1879, Father Karekin Srvantsdyants, the Prelate of Agn, issued a decree to the public. The decree stated that a joint summit of the religious and political leadership of the city had come to the conclusion that certain pernicious and unnecessary practices had taken root among the people of Agn and the surrounding area. The leadership of the community had made the decision to put an end to such practices. A committee had been formed, made up of prominent local figures, which had presented a program of economic reforms to the meeting, after which the meeting had agreed to the plan and to its implementation. Thereafter, the decree had been written and was dispatched to every Church in Agn, to be read publicly. Priests and neighborhood trustees were tasked with the implementation of the decree and its implementation [78].

Specifically, in the decree, the Prelate criticized the generous use of wine and liquor during wedding ceremonies in the area’s churches. Furthermore, the Prelate forbade drunkenness, writing that, firstly, “it clouded men’s reason and was the mother of all sin,” and that secondly, “during celebrations, it was often the cause of unruly behavior” [79].

The edict also called upon the people to put an end to many mourning practices, including the pulling out of hairs, the tearing out of collars, and the use of dirges, because they were “unnatural and manifestations of dishonesty.” Instead, the edict encouraged the faithful to pray for the salvation of the decease’s soul and for its eternal rest. These, and many other customs, according to the edict, were having a destructive effect on the community [80].

The decree made a particular point of imploring women to put an end to these above-mentioned practices, encouraging them to refrain from spending money on such lavish displays, and to instead invest the money in the preparation of new schoolmistresses who would work in the local schools [81].

- [1] Arakel Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, 1020-1915 [Agn and its People, 1020-1915], Volume I, Bucharest, 1942, pages 65-66.

- [2] Ibid., page 66.

- [3] Ibid., pages 67-68.

- [4] Ibid., page 68.

- [5] Toros Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar [Agn, Readings on its Culture and History], Volume I, Istanbul, 1955, page 25.

- [6] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, pages 66-69.

- [7] Ibid., page 69.

- [8] Ibid.

- [9] Ibid.

- [10] Arakel Kechian and Mgrdich Barsamian, Agn yev Agntsin, Paris, 1952, page 293.

- [11] Ibid., page 293.

- [12] Ibid.

- [13] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 69.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Ibid., page 70.

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] Ibid., page 71.

- [18] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 24.

- [19] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 71.

- [20] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 23.

- [21] Ibid., page 23.

- [22] Ibid.

- [23] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 72.

- [24] Ibid., page 72.

- [25] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 24.

- [26] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 72.

- [27] Ibid., page 73.

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] Ibid.

- [30] Ibid., pages 73-73.

- [31] Ibid., page 74.

- [32] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 24.

- [33] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 74.

- [34] Ibid.

- [35] Ibid.

- [36] M.S. Kaprielian, Agna Kavaraparpare yev Arti Hayeren Lezoun [The Agn Dialect and the Modern Armenian Language], Vienna, Mkhitaryan Press, 1912, page 136.

- [37] Ibid.

- [38] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 24.

- [39] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, pages 74-75.

- [40] Ibid., page 75.

- [41] Ibid.

- [42] Kaprielian, Agna Kavaraparpare…, page 133.

- [43] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 75.

- [44] Kaprielian, Agna Kavaraparpare…, pages 131-132.

- [45] Ibid., pages 131-132.

- [46] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 75.

- [47] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 24.

- [48] Ibid.

- [49] Ibid., pages 24-25.

- [50] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 76.

- [51] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 24.

- [52] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 76.

- [53] Ibid.

- [54] Kaprielian, Agna Kavaraparpare…, page 137.

- [55] Ibid.

- [56] Ibid., page 138.

- [57] Ibid.

- [58] Kechian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 77.

- [59] Ibid.

- [60] Ibid., page 78.

- [61] Kechian and Barsamian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 301.

- [62] Ibid.

- [63] Ibid., page 302.

- [64] Ibid.

- [65] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 25.

- [66] Kechian and Barsamian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 532.

- [67] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 25.

- [68] Ibid., page 25.

- [69] Kechian and Barsamian, Agn yev Agntsin, page 532.

- [70] Ibid., page 533.

- [71] Ibid.

- [72] Ibid.

- [73] Ibid., page 534.

- [74] Ibid., page 535.

- [75] Ibid., page 291.

- [76] Ibid.

- [77] Ibid., page 290.

- [78] Azadian, Agn, Nyuter ir Mshaguytin ou Badmutyan Hamar, page 12.

- [79] Ibid., page 12.

- [80] Ibid., page 13.

- [81] Ibid.