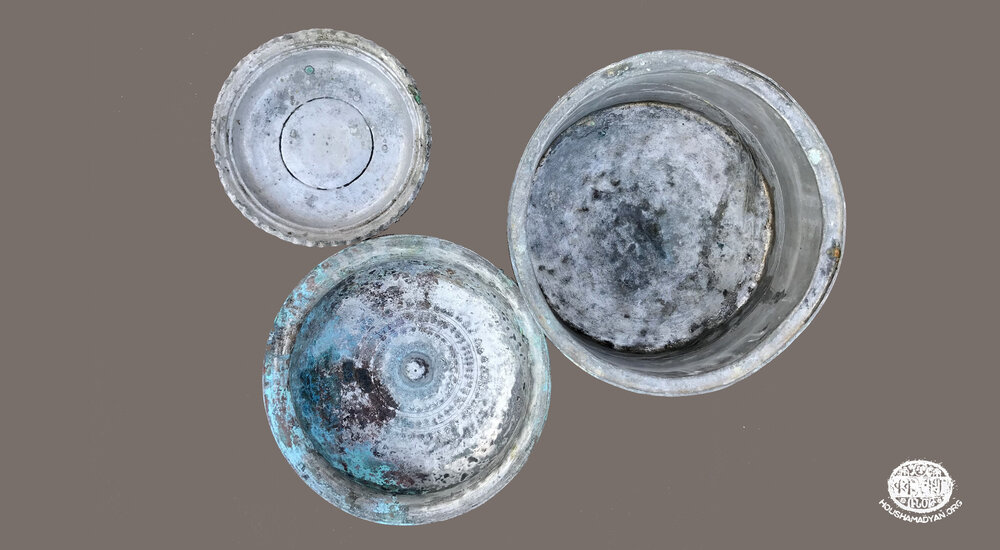

Duzdabanyan collection - Yerevan

The Secret Language That My Family Knew

Author: Ani Duzdabanyan-Manoukian, 05/10/2021 (Last modified: 05/10/2021)

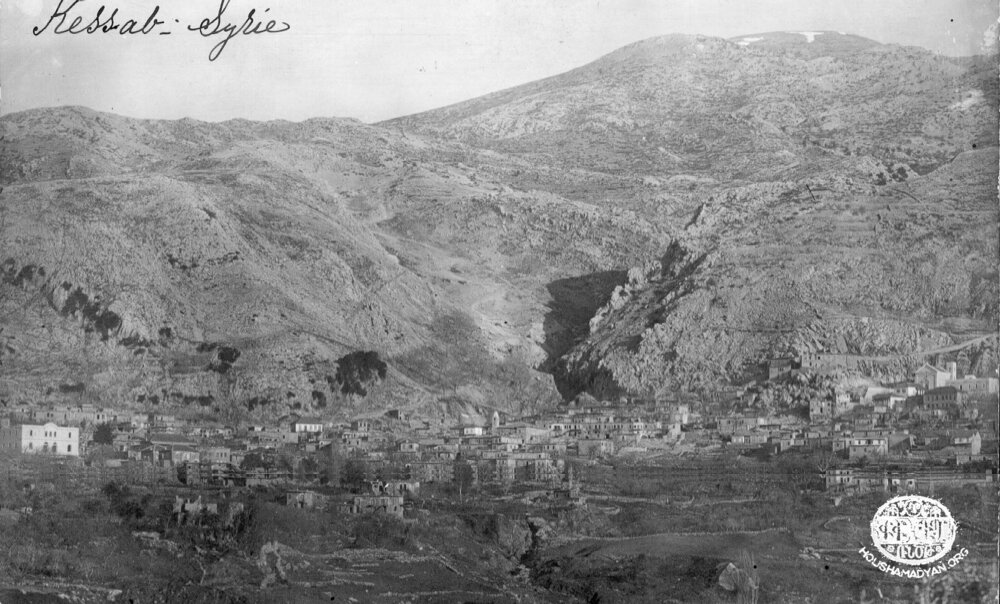

When I was a child, the adults in my family spoke a secret language, the Kessab Armenian dialect. They used this language whenever they needed to conceal their conversations from us, the children. This dialect was spoken by my paternal grandfather, a descendant of a survivor of the Armenian Genocide from Kessab; and my grandmother, who, like any true Kessabtsi wife, had learned it over her 20-plus years of marriage, just as she had learned how to cook, sing, and skillfully turn a coffee cup upside-down on a saucer for a session of fortune telling.

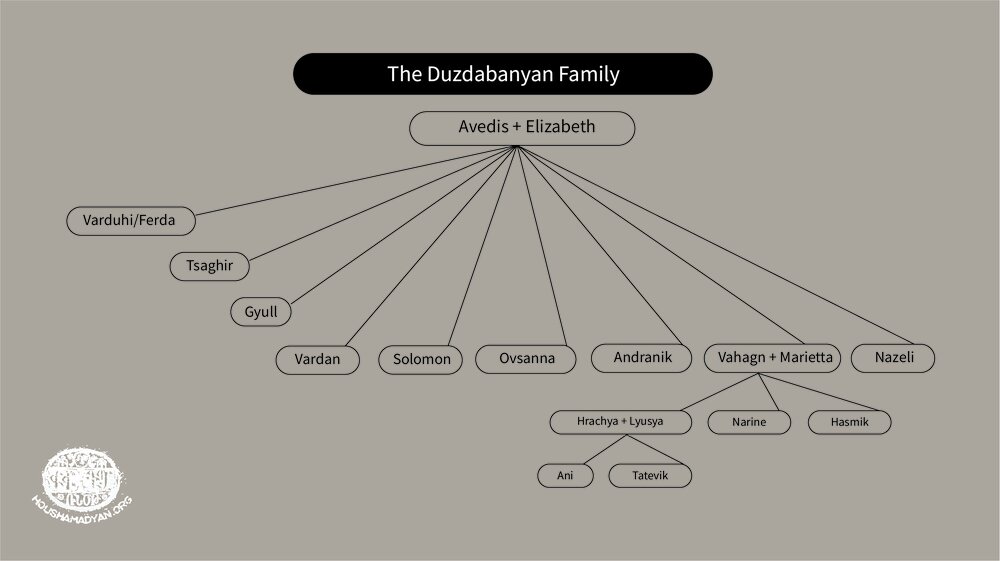

Our surname is Duzdabanyan. In Turkish, düz taban translates into “flat foot.” Presumably, one of my ancestors suffered from this physical deformity. According to Hagop Tcholakian, the author of a three-volume work on the Armenians of Kessab, the Duzdabanyan family lived in the village of Sev Akhpyur (Black Spring). H. Tcholakian mentions that my family was one of the three large families in Kessab that consisted of more than 30 members in 1911. That number decreased to five in 1920, after most of the family had moved to Beirut, Lebanon, after surviving the deportations during the Armenian Genocide. Some were forced to march to the deserts of Jordan, others to Deir Ez-Zor.

Years later, their tale of deprivation and torment became a bedtime story told by Ashkhen Baboudjian, Avedis’ granddaughter and my father’s cousin. She still remembers her mother’s reluctance, followed by resigned obedience, when she asked her to tell the story of the survival of Avedis and Elizabeth Duzdabanyan. “When the order to leave Kessab was issued, the apricots and prunes were ripe on the trees. The grain had already been harvested, but hadn’t been milled yet…” That’s how Tsaghir, Ashkhen’s mother and Avedis’s daughter, would begin the story of her unfortunate parents.

After receiving the deportation orders, the Catholic and Apostolic Armenians of Kessab packed their belongings and set off on their march towards the unknown. Among the Armenians in this caravan were Avedis and Elizabeth, who silently left their native land with their daughter, Ferda, and a baby boy who later died on the journey. My great-grandfather was a shoemaker, and quite a famous one. When they reached Homs, a sheikh learned that Avedis could repair shoes and even make new ones. He decided to take him and his family under his wing, thus saving them from certain death. Avedis and Elizabeth lived in Homs until the end of World War I, when British forces occupied Syria.

Upon receiving news that their fellow villagers had returned to Kessab, the Duzdabanyan family also returned, but they found their home in ruins. They rebuilt it and continued living in their native land. Ashkhen’s mother was born after the family’s return, as were all seven children of the family. During the death march, Avedis had managed to save seven orphaned sisters, who returned with him to Kessab and later followed him to Armenia. In 1946, Avedis, a member of the Social-Democrat Hunchak Party, was among the thousands of repatriates who immigrated to the motherland with hopes of a better life. This dream destroyed Avedis, once so renowned and admired. He quickly discovered that the Soviet promise was a lie. Unable to adapt to the conditions in Armenia, he fell ill and died. His wife Elizabeth suffered from severe dementia. My father often recalls how, when he would play outside their house in Yerevan with his friends, Elizabeth would come outside with a stick in her hand and shout at them: “Go away, Turks!”

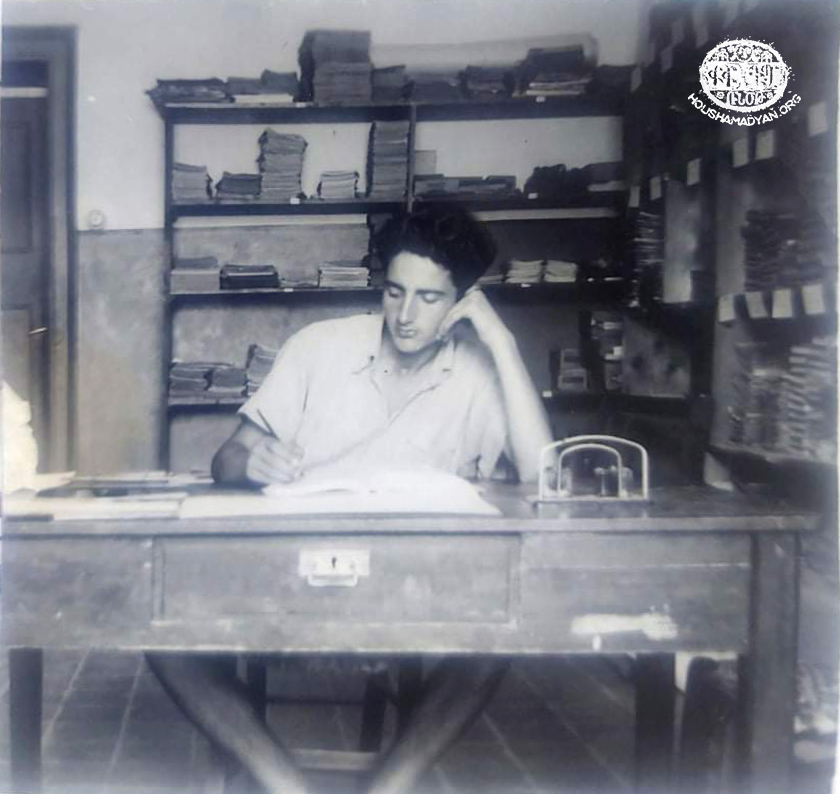

Despite all the challenges they faced, Avedis Duzdabanyan’s sons achieved success in Armenia as sculptors and builders.

I often think about all the questions that I could have asked Avedis’s children when they all gathered in my house over harissa. To make this dish, my grandfather, Vahagn, would spend all night melting chicken bones into the wheat with a wooden spoon (my grandfather was a former student of the Melkonian Educational Institute in Cyprus, but had never graduated due to his move to Armenia). Throughout my childhood, my mother continued to use that same spoon in her kitchen.

Whenever my elders spoke in their “secret” language, I endeavored to decode what they were saying, but the best I could do was only catch a familiar word.