Music gallery - I

17 August 2011 (Last modified: 2 April 2013)

Editor's note

It is Houshamadyan’s aim to try to understand and to introduce, as far as possible, the variegated and heterogeneous Ottoman Armenian world – in all the places where Armenians lived in the Ottoman Empire. It is simple for us to see the often great differences in Ottoman Armenian culture between one place and the next. We do not want to ignore this diversity that exists in the same community group. On the contrary, we consider it a different ingredient in the Ottoman Armenian legacy, and thus a subject worthy of study without bias.

It is the same in the field of the art of song. Armenians have not spoken or sung in Armenian everywhere in the Ottoman Empire. We find geographical regions in the Ottoman Empire where the local Armenians, different especially to those of the many places in the Armenian highlands, have lived less isolated lives or, over the centuries, found themselves to be in a minority situation. The impact of the social environment and cultural influences has also left its mark on the language and the songs these groups of Armenians used. For this reason there have been areas of Armenian settlement and towns and cities where the Armenians’ mother tongue has been Turkish, and the songs they have created and sung have been in that same language.

It is possible to say the same about the some of the musical instruments the Ottoman Armenians used. Some of them, like the ud (oriental lute) for example, have practically no place in contemporary Armenian music. But as we’ve already pointed out, Houshamadyan’s aim is not to wipe out or ignore these differences. We want to reconstruct a past that is as accurate as possible. Using this principle we will attempt to present the Ottoman Armenian just as he or she was, staying away from ideological, aesthetic or various politico-cultural influences.

We think that the list of songs presented below best defines the great diversity of Ottoman Armenian culture. In it we can find classical Armenian songs still heard on Armenian stages today. But there are also other songs whose tunes and the sounds of the instruments used may seem alien by those who admire contemporary Armenian music. In other words the collection of songs and singers are often incoherent and will be difficult to place within a general theme. But from our point of view, these songs also have a common denominator; they have been listened to and sung by Ottoman Armenians – in their home cities and towns or villages or, later, in the 1920s, outside the Ottoman Empire, in the newly-formed exile communities. This means, of course, that such songs have accompanied the Ottoman Armenians and have formed part of daily lives. Our aim is to give a place in our website pages to all such songs, knowing well that they all have their place in the Ottoman Armenians’ general legacy.

Houshamadyan’s editorial board would especially like to thank Ian Nagoski who put the following songs at our disposal when we were preparing this page on our website: ‘Chinari yares aghchig’ (sung by Karekin Prudian), ‘Keriyin yerke’ (sung by Karekin Prudian), ‘Anduni’ (sung by Armenag Shahmuradian), ‘Hai aghchig, char aghchig’ (sung by Duzjian), ‘Tamzara’, ‘Usge gukas’ (sung by Nishan Keljikian), ‘Hop pala’ (sung by Stepan and Haigaz), ‘Grung’ (sung by Zabelle Panosian). We also utilised Nagoski’s text in preparing the biographies of these singers. We should point out that all these songs, as well as the singers short biographies, are to be found on the three CDs prepared by Nagoski called ‘To What Strange Place: The Music of the Ottoman-American Diaspora, 1916 – 1929’, a sprawling 3CD set compiled by Ian Nagoski in 2011 (www.tompkinssquare.com). We should also like to thank the www.excavatedshellac.com, that put the song ‘Menk angeghdz zinvor enk’, sung by Levon Hampartsumian, and ‘Gigo’ sung by A. Kevorkian at our disposal.

Karekin Prudian

Among the most prolific performers of Armenian Ottoman folk music of the 1910s and 1920s, singer Karekin Prudian, born in Dikranagerd (Diyarbakir) in 1884, arrived in the US in 1903 and settled in West Hoboken, New Jersey, in a large Dikranagerdtsi community. He recorded 18 tracks as a singer in 1915-1916 for Columbia and Victor records. 17 were in Turkish and 1 was in Armenian ("Iprev Ardziv" the ode to General Antranig written by Ashugh Sheram.) When fellow Dikranagerdtsi M.G. Parsekian founded his record label in West Hoboken in the early 1920s, Prudian's record of Glorig Manch with Hasagt Partsr was the first release. Hasagt Partsr, also known as Kale Kale, became a very popular song for Armenian-Americans until today. During the 1920s, Prudian recorded 22 songs, 18 in Armenian and 4 in Turkish, for the M.G. Parsekian and Sohag record companies, both owned by Armenians in New Jersey and New York. Many of the Armenian songs were composed by Hovsep Shamlian. On this one from his Parsekian sessions, a girl is compared to a poplar tree (chinar). The musicians are most likely Harry Hasekian (violin) and Edward Bashian (ud), who are pictured on the label. Karekin Prudian worked in the photoengraving business by day, and died in 1977.

Text by Harry Kezelian

Chinari yares aghchig (My love is like a poplar tree)

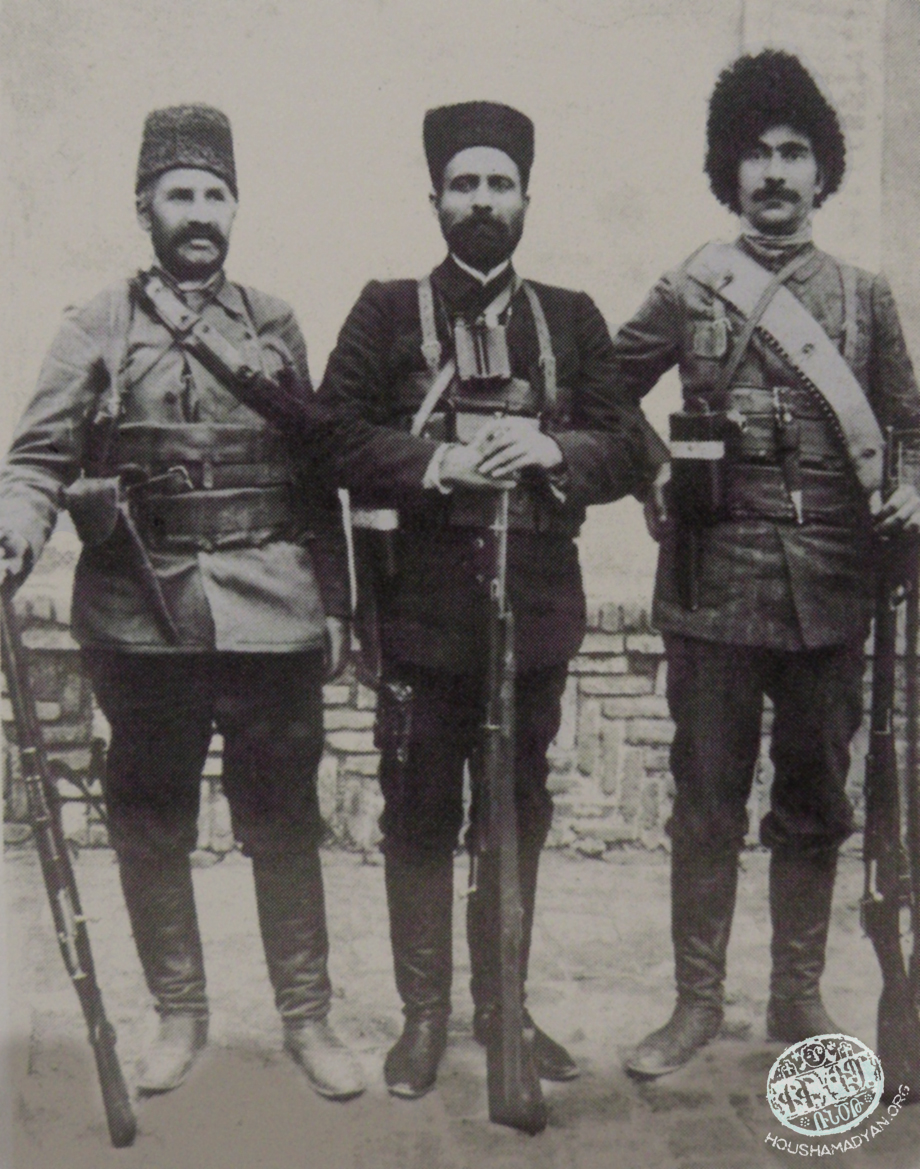

The second song sung by Karekin Prudian is the well-known revolutionary song dedicated to Keri. Keri, or Kavtar Arshag Kalfayian, an ARF (Dashnaktsutiun) fedayi, operated in Sasun and Vasburagan during the Abdulhamid II regime from 1903-1905. From 1908 to 1912 he was a participant, with Yeprem Khan, in the Persian revolution. He was appointed commander of the 4th Armenian Volunteer Regiment after the start of the First World War. This military unit was attached to the Russian army and operated on the Russo-Turkish front. He was killed in 1915, during an operation at Rawanduz, in present-day Iraq. The song was composed on the occasion of his death.

Keriyin yerke (Keri’s song)

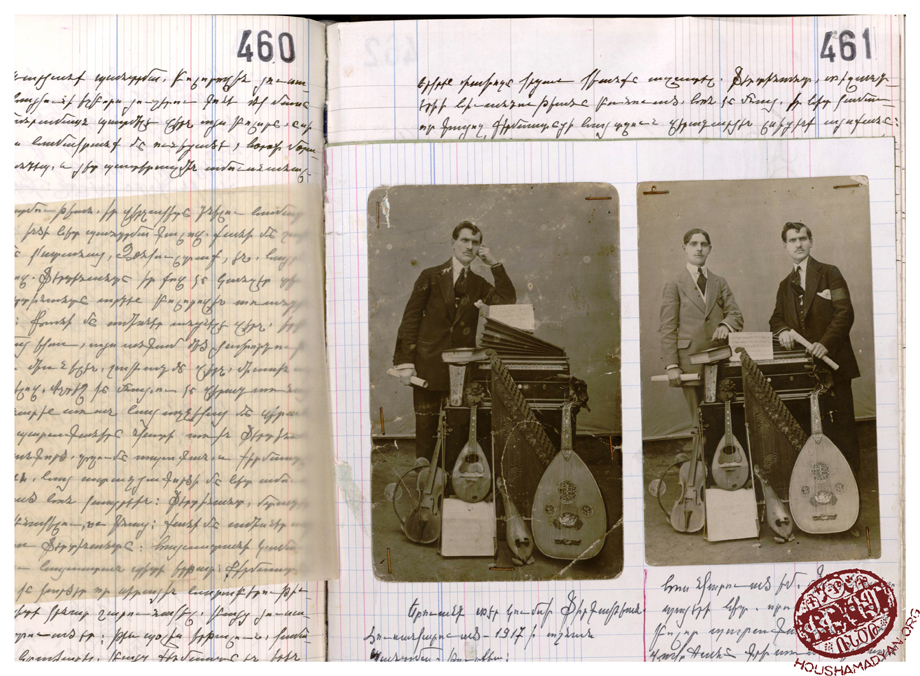

Armenag Shahmuradian

Shahmuradian was the son of a blacksmith and was born in Mush, Eastern Anatolia in 1878. He received his education in the seminary of St Garabed monastery, Mush, then in the Holy Echmiadzin Kevorkian seminary, and finally in the Nersisian School in Tiflis (Tblisi). He was known as the ‘nightingale of Daron’. Shahmuradian was a student and friend of the famous Armenian ethnomusicologist Gomidas Vartabed. He received his musical education in Paris. He was in the United States of America during the First World War. This performance of one of Gomidas’ compositions was made in 1917 during one of Shahmuradian’s U.S. tours. Nearly every Armenian home with a gramophone in the U.S. included his records. He died in 1939 in Paris.

Kele Kele

(sung by A. Shahmuradian, in CD, The Voice of Komitas Vardapet, Traditional Crossroads, 1995)

Hov Arek (soloist unknown)

The first person to sing this song is thought to be Armenag Shahmuradian, bearing in mind that this is what is stated on the CD sleeve. But according to experts (and for this we express our thanks to Andranik Michaelian, and for his advice) the voice heard is unlike that of Shahmuradian. As to who is actually singing – this remains a mystery to us.

Hov arek, sarer chan, hov arek,

Im tartin tarman arek.

Sarere hov chen anum,

Im tartin tarman anum.

Amber, amber, mi kich zov arek,

Varar antsrev tapek, dzov arek,

Kesh martu or-areve

Sev hoghi dagov arek.

M. Duzjian

Nothing is really known about the udist and singer M. Duzjian who recorded 14 performances in the mid 1920s for the M.G. Parsekian and Pharos labels. He seems to have been one Mgrdich Duzjian, born May 1896, who emigrated in 1921 and lived in Union City, New Jersey. The title of the song, recorded about 1927, is ‘Armenian girl, naughty girl’.

Hai aghchig, char aghchig (Armenian girl, naughty girl)

D. Berberian

Very few is known about this clarinetist who recorded for the tiny early 1920s vanity record label of singer and violinist Vartan Margosian (January 1891 - September 1965). Margosian’s band, including Berberian, kanun (oriental zither) player Boghos Boghosian and udist H. Karagosian released around 20 discs of spirited, if amateurish, folk music. By the late 1920s Margosian was living in the Bronx in New York and had recorded music for the equally obscure Sokhag label and one disc, accompanied by Stepan & Haigaz Simonian, for Pharos. The tamzara is a very popular line dance among the Armenians of eastern Anatolia in 9/8 time.

Tamzara

Nishan Keljikian

Nishan Mardiros Keljikian (July 1886/7 - October 1962) arrived at Ellis Island in November 1911 at the age of 25 from Mezre (actually Elâzığ) in Eastern Anatolia. Keljikian joined his brother in Chelsea, Massachusetts and worked first as a barber and then as a surveyor for the city of Medford. He recorded only a few songs, including this one around 1929 for Pharos with a group of two violins, piano and tar, the long-necked, double-bowled lute. The song clearly expresses the Armenian immigrant to America’s worries, his expectations about America as well as the disillusionments he has lived.

Usge gu kas (Where are you from?)

Ameriga esbas gorapats

Nshanadzes antin mnats

Teyev unim badar me hats

Peranes chor, achkes tats.

Usgits hanetsir ays ko dan,

Menk hos yegank anonk u՞r yertan,

I՞nch dun unink, inch al vartsank

Shevaretsank, menatsink, gortsank.

Ameriga tun miyain gas,

Haieren chi kar kez vnas,

Yerp esgsink khosil chakhpat

Badrasdenk mez melting pot.

Khergetsir tram, misionar,

Brod erir mez angadar

Yegur yeghir mez hokadar

Menk chenk ellar kezi odar.

Stepan & Haigaz

Armenian violinist Stepan Simonian was a native of Mezire (Mamuretul-Aziz, present-day Elazığ) in Eastern Anatolia, province of Kharpert. He arrived at Ellis Island in 1907, at the age of 20, and was headed for Haverhill, Massachusetts, along with his 16 year old bride, Sofia (a Kharpert Assyrian), his parents and siblings. Their surname given on the records was Alexanian, but Stepan later changed his last name to Simonian, in honor of his father Simon. Beginning in 1927, he recorded several sides for Columbia with his son Haigaz (American name, Henry) on the piano and Shmon Arslen (apparently another Assyrian) on vocals. Stepan and Haigaz later recorded a group of performances with the Armenian-owned Pharos Records. This recording, entitled Hop Pala (hoppala, an exclamation which is difficult to translate) is notable for its unusual metre.

Text by Harry Kezelian

Hop Pala

Levon Hampartsumian

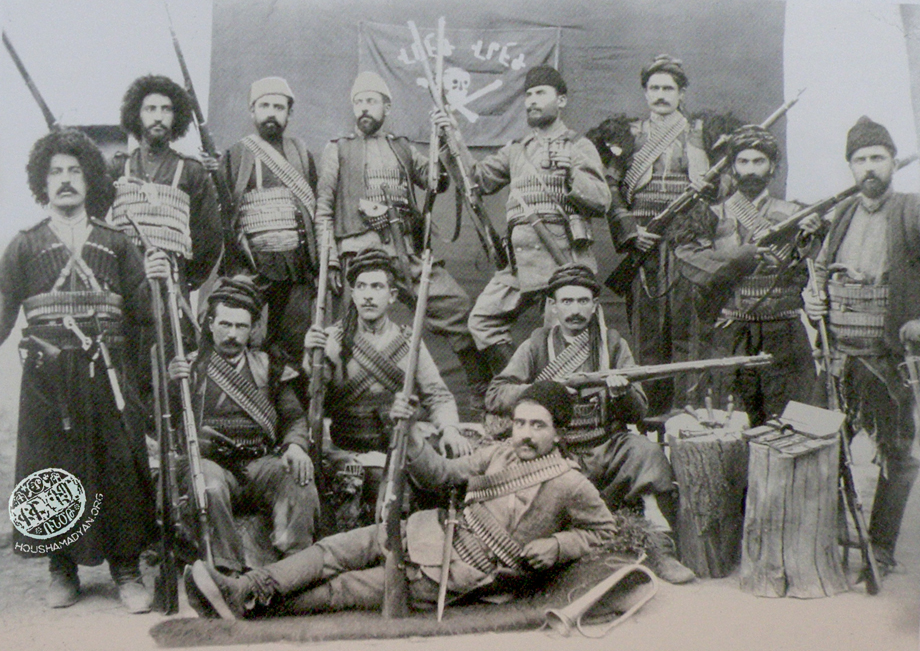

This Odeon recording was made probably between 1913 and the 1920s. The singer's name is Levon Hampartsumian, and he was accompanied by two violinists. The song title is ‘Menk angeghdz zinvor enk’ (We are sincere soldiers). It was composed at the end of the 19th century on the occasion of the Khanasor foray. In July 1897, about 250 Armenian fedayis of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutiun) succeeded in crossing the Persian-Turkish border and attacked the Kurdish Mazrig tribe at Khanasor. This was a punitive response, bearing in mind that armed members of the Mazrig tribe were direct participants in the anti-Armenian massacres in Van in 1896.

Menk angedz zinvor enk (We are sincere soldiers)

A group photograph of the fedayis who took part in the Khanasor foray. Standing, in front of the flag, from left to right: Prince Hovsep Arghutian (deputy commander of the expedition), Vartan (commander) (Source: Hagop Mandjikian, Memorial book of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, an album-atlas, 2nd edition, Los Angeles, 2001)

A. Kevorkian

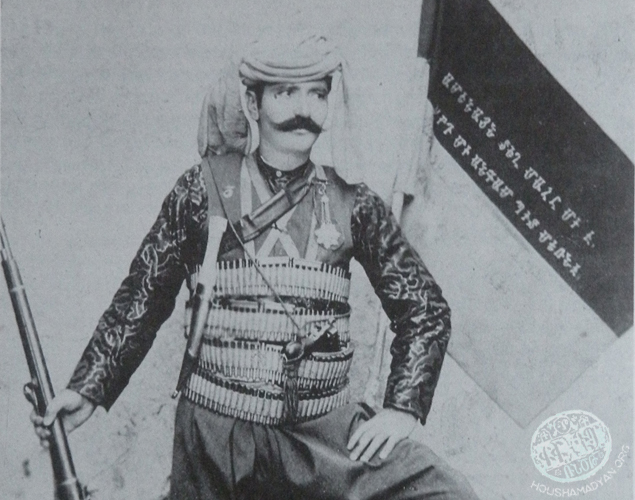

Kevorkian sang these tracks in January of 1929 in Los Angeles, and is accompanied by violin, ud, and Mesrob Takakjian on clarinet. Other recordings from this session were released by Columbia. The first song appears to be based on a number of popular tunes and has new lyrics. The second song is dedicated to the well-known fedayi Antranig Ozanian (1866-1927), who was born in Shabinkarahisar. From 1897 to 1904 he operated in the Van, Akhlat and Sasun regions.

Gigo

Antranig’s march

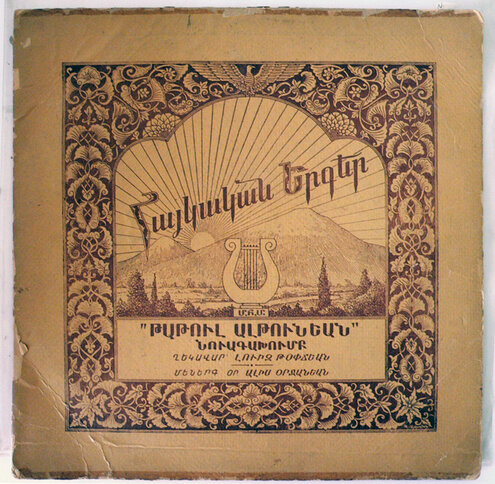

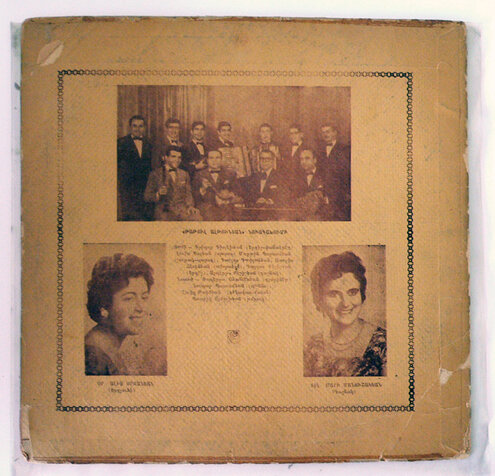

The "Tatul Altunian" Ensemble (Argentina)

These recordings were made in the 1950s. The ensemble was directed by Avedis Topdjian (1909-1975). He was born in Ayntab, survived the genocide then, with his family, settled in Aleppo, Syria. He emigrated with his family to Argentina in 1926. He became a well-known photographer in Cordoba and founded the "Tatul Altunian" Ensemble in which he played the kanon (oriental zither). He had been given this instrument in Argentina by another survivor, Mr Sahag who was a master instrumentalist in the Ottoman era. It is said that during the genocide the perpetrators cut the tendons to his fingers so that he could never play the instrument he loved so much, ever again. As a result his fingers were always curled into his palms. But Mr Sahag was determined to play again. He had special rubber finger stalls made that he put on his own fingers to allow them to move and, through sheer willpower, was once more able to make the kanon’s strings sound sweetly when he plucked them.

Zghchum (Repentance)

This song was very popular from the 1920s in the Greek and Armenian communities formed from former Ottoman citizens who had settled in the United States of America.

Yegur, yegur (Come, come)

Zabelle Panosian

Zabelle Panosian (May, 1893 - January 1986) was 23 years old and the mother of a six-year-old daughter when she recorded the famous song Grung (Crane), in about April 1917. It is thought that this song was written in medieval times. It had already been recorded in Paris by Gomidas Vartabed in 1912. Panosian recorded only eleven songs in a period of about ten months. She arrived in the USA in 1907, lived for some time in Boston and later in Manhattan, New York, and travelled to Paris in the 1920s.