Zeytun – Religious customs

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 20/6/12 (Last modified 14/7/15)- Translator: Ara Melkonian

In parallel with his daily life, the person from Zeytun being a traditionalist has, over the centuries, evolved family ritual ceremonies and customs that are unique and differ from those of the surrounding area. Thus, beginning with wedding ceremonies, it is the custom, as in all Armenian-inhabited areas, that when two families feel sympathetic to each other and want to expand their link, they betroth their infant children to each other, each family then calling the other khenami (in-law) and having a closer relationship. When the children reach marriageable age (in Zeytun the engagement age is 15-17 for young men and 12-14 for girls), formal discussion ceremonies begin between the families concerning the young peoples’ marriage. If no one has been chosen, but there is a young man in the family of the right age, the women of that family, mainly the mother, begin to look for a prospective bride and take an interest in the local girls, especially taking note in church of those that are grown-up. When they have selected one, they suggest their choice to the young man and, after getting his assent (although it should be said that the young man is bound to accept his mother’s suggestion, even if he is in love with someone else), [1] they find an opportunity to visit the prospective girl’s home and, during their conversation, ask the prospective bride for water. This is a sign to the girl’s parents that the guests have come to see their prospective daughter-in-law. After they have departed, the girl’s parents decide whether to proceed or not, and send word accordingly to the young man’s home. If they have said, ‘May God do the good thing,’ then they answer is positive.

Betrothal

The young man’s father, through the priest, sends the girl’s family either a gold ring, a pair of gold bracelets or several ghazis (gold coins) as a sign of the couple’s betrothal which are given to the prospective bride on various occasions during the years of their engagement, so that, by collecting them, they will later form her forehead jewellery or necklace. [2] Several of the young man’s closest relations, bringing honey, nougat, walnuts, raisins, seeds, and occasionally gold coins, accompany the priest to the girl’s house. A large carpet is laid with comfortable couches on it to welcome the guests and priest to the prospective bride’s house. Her father greets them and invites them to be seated, then calls his nearest and dearest to join the guests. Hospitality begins with djigara (tobacco) and nargilo (hookah) being brought in, after which all are served with oghi (raki) and wine with the appropriate side dishes (raisins, walnuts, honey, apricot sheets, figs, stuffed partridge and chicken). The priest begins the conversation, saying, ‘Well, don’t they ask the visitors why they have come? If the Lord wills it and God sees it is good, you have spoken about giving your daughter to this family’s son. Is this right? If so, take this token [a ring].’ Then, blessing it, he gives the ring to the girl’s grandmother; she passes it to her son, in other words the girl’s father; in his turn he gives it to his wife so that the latter can put it on the girl’s finger. While this is happening, the girl’s relatives announce, ‘May God grace it, it is good. Ten people wanted her before this, but it seems that this is her fate.’ The girl, entering the room, kisses everybody’s hands. Then the meal is brought with special dishes for the occasion, such as soghanle, hadruz, micheov keofte, havget dabgilo and so forth. If, however, it is a time of fasting, then the appropriate food is served. They eat after the priest has said grace and congratulate one another. At the end of the visit, when the guests are due to leave, the priest once more says a prayer. The now-engaged girl kisses everyone’s hands once more. The priest receives the gift of a towel, and the guests, wallets. [3]

Visiting the engaged girl’s home

On the Friday of that week, the young man’s father summons a brave (fighting) man from Zeytun and commissions him to invite their friends, comrades, neighbours and relatives to visit the prospective daughter-in-law’s home.

On the Saturday the young man’s people kill a sheep, fill its stomach with walnuts, meat and dried fruit, and cook it. Rice pilav is also prepared. They then dress in their best clothes and in a large group, solemnly go to see the engaged girl, taking the cooked sheep, honey, wine and bread with them.

The girl’s family, having laid a long carpet and put couches on it, await the in-laws. There is plentiful hospitality, drinks, good wishes and joy. Then someone takes a plate and collects the bride’s gift, usually money, from those present. This is given to the bridegroom-to-be so that he can buy gold coins for his fiancée. [4]

The engagement usually lasts from one to three years, during which the engaged couple have no right to see one another. Even if they meet by chance, they must part, turning their heads away. The young man’s family, on every feast day, goes to the girl’s house with gifts and a great deal of food. [5]

The wedding

The priest’s visit (babun hantibil).- This expression is symbolic: it is the harbinger of the marriage. Several weeks before the wedding, the young man’s father prepares a delegation, comprising the priest, several friends and notables from the neighbourhood, and sends them to the in-laws’ house, where they are received with special hospitality. After they have eaten and drunk, they give the reason for their visit – they have come to arrive at decisions concerning the wedding. Often the bride’s family will be reticent, want to delay it, saying that their daughter is still too young. Then they raise the question of the cost of the preparations for the wedding – that of clothing, several pairs of shoes, the groom’s red coat (barekod), his brothers’ sandals, the neighbours’ slippers or handkerchiefs and so on. If they come to an agreement, then the purchase and sewing of the wedding clothes begins. [6]

It is significant that when preparations are begun on the week of the wedding, on the Monday (Irgushapten), things start with cleaning rice for pilav. Rice is the symbol of plenty and it is not by accident that when the bride leaves, rice is thrown over her, perhaps recalling the wedding, in the 2nd century BC, of the Armenian King Ardashes I and Queen Satenig.

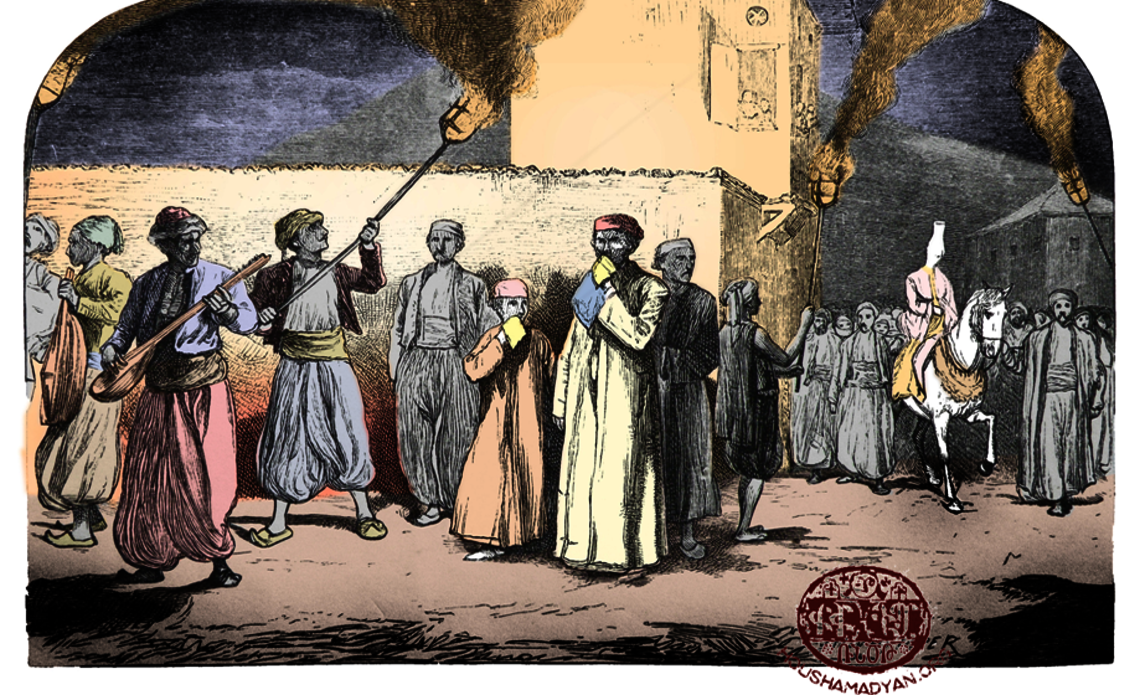

On the Tuesday women gather and bake great quantities of bread for the wedding. At the same time the young people are sent to gather wood. 30-40 young men, wearing red coats, with silver chains on their chests and with pistols in their belts, gather together. The groom’s father loans them mules as well as giving them great quantities of oghi, wine, bread and other traditional things. They then head for the forest called Khanos. The young men occasionally fire their guns, so that everyone knows about the wedding. Often other young men join the party, dressed in the same way. They sing, joke and fire their guns during the entire journey. They stay for a night in the forest enjoying themselves, then the next day, having loaded the mules with wood, they return to the wedding house with the same noise and joy, being met at the village entrance by musicians playing drums and pipes. They continue enjoying themselves after handing over the load, this time having a target shooting competition. They are entertained in the groom’s house in the evening. After that the wedding table is always open to all guests. It should not be forgotten that the groom’s father sends several loads of wood to the bride’s house. [7]

On the Thursday the young man’s father sends the azabbashi (godfather) a gift – either a silver chain for his pistol or a new pair of shoes. The godfather puts on his magnificent red coat and ties a silver thread edged handkerchief on it as a sign of being a godfather. He gets pastries suitable for the occasion from the market and gives one to each person who will be invited to the wedding, saying, ‘I wish the same for your child too; please come to the wedding.’ Meanwhile bread is continually being made in the house, meat is being beaten, keofte is being made, as well as the house being cleaned thoroughly. The bride and groom are also really getting ready: they fast, repent and have confession. Sometimes, if they are rich, they distribute alms to the poor. [8]

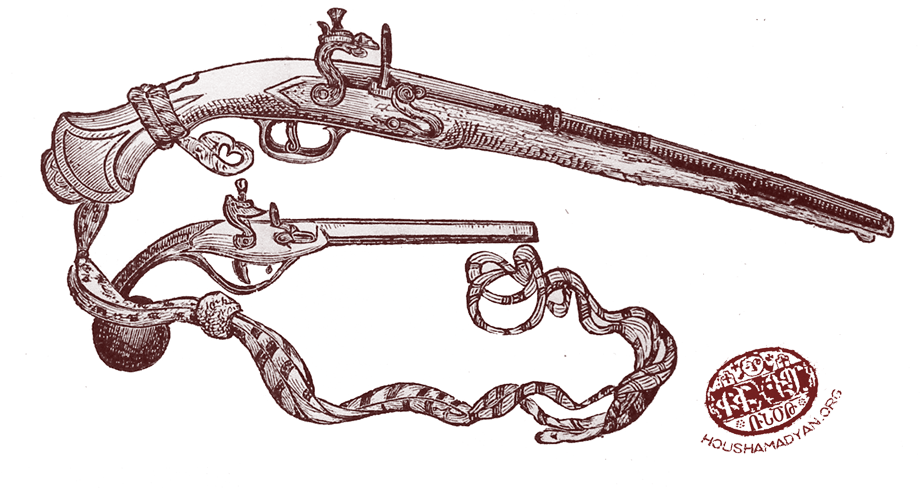

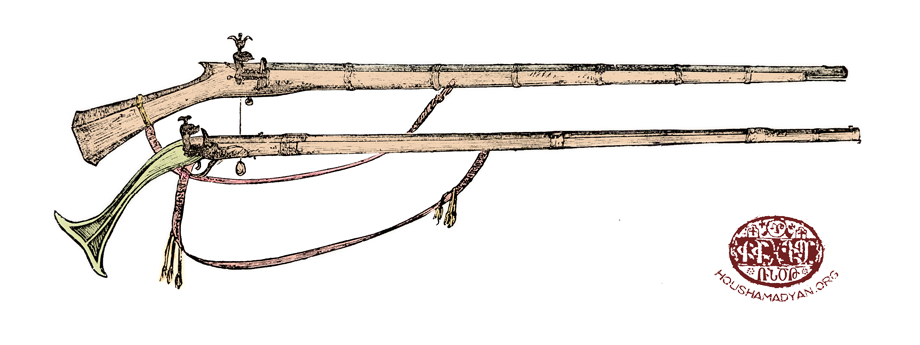

Guns and pistols used in the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the 19th century. (Source: Henry J. Van-Lennep, Bible lands. Their modern customs and manners, part II, London, 1875)

The main day for the wedding is Friday. Several cauldrons of dagabur, eaghtsiudz iusb, oruzabur, soghanle and so on are cooked in the morning. Relatives, friends and neighbours don’t arrive empty-handed either; they too bring different dishes, fruit and sweets. The women fill their pockets with walnuts, raisins, apricot sheets, hazelnuts, sugar etc, so that they can distribute them among the children.

They go to the church to bless the marriage tokens (nishon orhnel) – the gold ring to be given to the groom and the bride’s gold bracelet that are tied together with a colourful silk ribbon. The priest, in the presence of the groom’s friends and relatives says, ‘With the sign of your all-conquering cross, Christ,’ and blesses theses symbols of marriage and a handkerchief full of raisins and seeds, by singing a canticle. While this is happening, those present collect their gift which is the priest’s portion. After the blessing the godfather stands at the church door, distributing the raisins and seeds to those present, as a hope they will enjoy the same. [9]

The next ceremony is the djarturumn (decoration). The groom’s family, accompanied by the priest and notables, to the beat of music, go to the bride’s house; the godfather carries the bride’s clothes etc (ghutni khumash), her dress and a pair of yellow shoes on a large circular tray he holds on his head. When they get to the door of the bride’s house, fireworks are let off (giulbeng). The women, taking the tray of clothes etc, and led by the patriarch of the house, dress the bride to the accompaniment of singing and dancing, and then henna her hands. When they return the tray to the godfather, they place a cup of wheat, a spoon, comb and a needle on it. Meanwhile the priest and deacon sing:

You are like an incense tree,

You will give forth good fruit,

You are a sweet-tasting fruit,

Holy Mother of God, we beg your pardon. [10]

The procession then goes to the groom’s house, to conduct the ceremony of ‘bathing the king’ (teakviur volo). They seat the groom in a large tub; the godfather holds a sword, like a cross, over his head, then they bathe the groom with hot water and soap, while singing the canticle ‘Today ineffable...’ It is then the godfather’s turn. After bathing him too, the young men who are not married wash their feet in the same water so that they may have the same good fortune. [11]

Then the bridegroom’s and godfather’s clothes will be blessed; this ceremony is called halav urhnek (halav, blessing of the clothes). The clothes, wrapped in a white parcel, are brought in – the coat, a sleeved shirt with tassels, a handkerchief, trousers, belt, turban and slippers, as well as the bride’s coat and cloth head-covering. After the blessing and dressing, they kneel before the priest who, after reading a bahbanich (prayer of protection), handing the bridegroom a sword, says, ‘God puts this sword at your strong waist, as a decoration for you. Be victorious over your enemies with it. Take it and keep it firmly.’ During the feast that follows, a further collection is made for the priest. Then the priest, with the bridegroom and godfather, with the others in procession, go to the bride’s house, where the pre-wedding ceremony is held – the joining of the bride’s and groom’s hands. [12] Then the groom, the godfather and their people, returning home with the bride’s relatives, begin to play joyful games, joking, singing and dancing, feasting and enjoying themselves. This lasts until dawn; there is a great crowd present. They light a bonfire after midnight, jump over its flames, and coat the young mens’ faces with a mixture of flour and soot and also fire guns into the air. This visit by the in-laws is called ‘to annoy’ or ‘annoyance’; they therefore begin to present strange demands such as: so-and-so has to stand with a bucket of water in each hand; another has to bite the onion hanging from the ceiling; someone else has to use grindstones to mill some wheat and eat it; two partridges have to be brought; water has to be asked for from the fountain; to prepare and serve keofte and so on. [13]

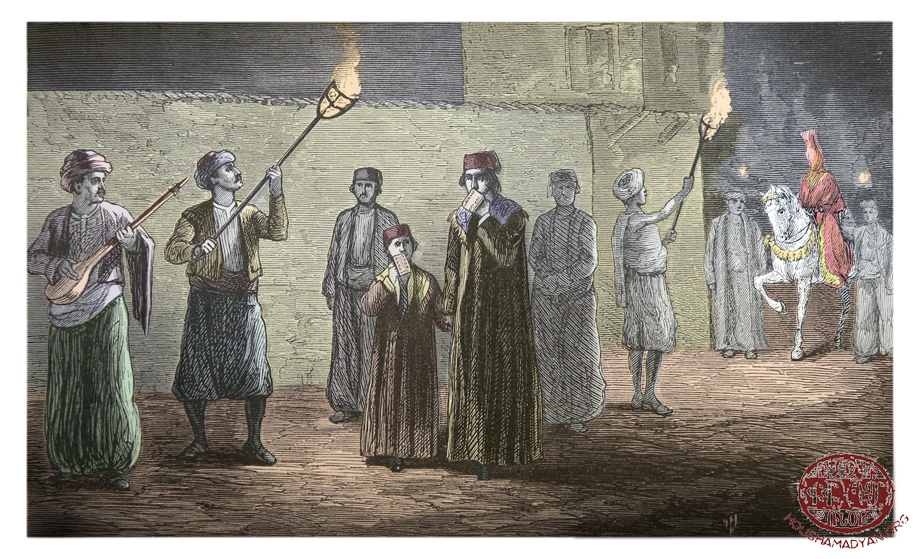

A sheep is killed just before dawn and madagh is prepared. Neighbours and relatives bring food too. The bells are rung, Mass starts in church and, when it is light, they go to ‘bring out the bride’ (hars hanel). At the bride’s house carpets have been laid and cushions arranged, and a spit roast and oghi prepared. The men sit down to eat, while the women, with the assistance of the priest’s wife, singing and dancing, dress the bride in her red and silk coats and rose-coloured slippers, into which they will have put a coin – the person who helps her on with them receives it as a gift. A large sheet is put on her head and veil over her face, and her forehead and neck are adorned with gold coins and jewellery and handkerchiefs are fixed to her red coat in various places. When she is ready to leave the house her brothers stand at the door to prevent her from going until they receive pairs of shoes as gifts. As the bride leaves the house, the priest’s prayers accompany the singing and dancing, the sound of the firing of guns by the young men and the boys’ shouts: ‘We cheated them, we got her!’ When she is seated on a horse, she cries, saying, ‘I cry but I go...’ The joyful procession takes the bride to the church. [14]

At the beginning of the marriage service, the bride and groom each have a cross on a silken cord tied around their heads; a cross-shaped censer is hung from the groom’s shoulders and an orange or apple, wrapped in a silk, tasselled handkerchief is given to him to hold. The godfather holds his sword, like a cross, over the couple’s heads during the entire service. At the end of the service, the maid of honour (harsnakiur) gives the priest a parcel, from which he removes a fez, which he puts on the bridegroom’s head and a ring; he distributes the apricot sheets and honey in the parcel among the children. Those present approach the married couple with their congratulations, the men kissing the cross on the groom’s forehead, the women that of the bride. As they leave the church, the priest and deacon, to the sound of cymbals, sing the canticle ‘The sun of justice...’, and then the schoolchildren sing any patriotic song, followed by the young people singing the following Turkish song:

It is pouring with rain, the ground gets wet,

This is joy for all the birds;

The fine lover is drunk,

Come moving, moving. [15]

Then all the young people shout ‘ Ku, lu,lu, ku, lu, lu!’ meaning ‘hurrah for the bride and groom.’ They seat the bride on a horse, and the bridegroom and godfather on a mule each, and the procession moves off, dancing and singing, to the groom’s house. On the way people from the houses along the route provide hospitality in the form of drink and fruit, also throwing handkerchiefs on the bride’s head; they then, holding the horse’s reins, ask for her to sing. [16]

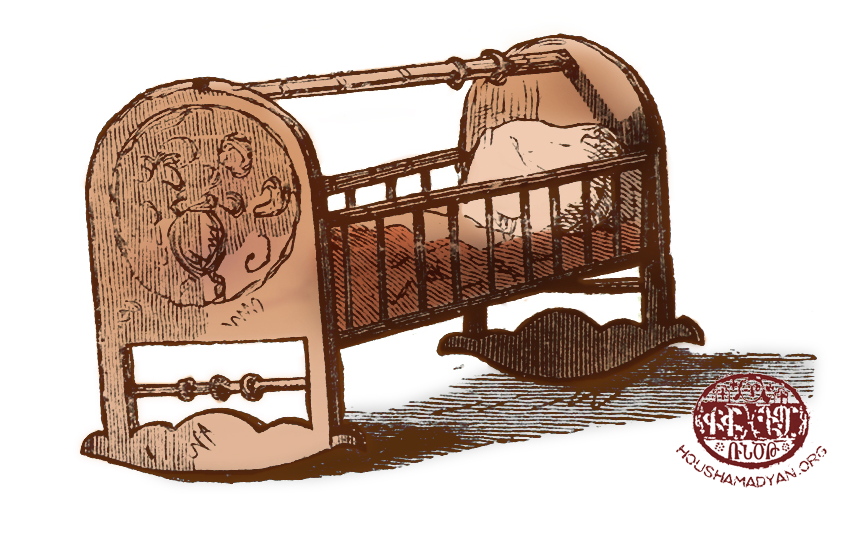

When they reach he groom’s home, the godfather brings a bread kneading tray to the bride. She mimes the actions of kneading dough, with the promise of being a humble, diligent daughter-in-law; at the same time the groom’s mother throws a handful of small coins (or cracked barley) from above, symbolizing plenty. At the threshold the bride’s father-in-law promises her a gift of a vineyard or field; in answer, the bride brings out a pomegranate from her breast, striking the threshold with it, scattering the seeds, expressing her wish that, like the seeds, she should be beautiful, healthy, have many children. Then they put a newly-born boy in her lap, so that her first-born will be a boy.

As soon as she enters the house, she is taken to stir the dinner cauldron, and then separated from everyone else by being put in a curtained room. The bridegroom, carrying a sword in one hand and a wrapped parcel of fruit in the other, accepts congratulations standing. There is feasting and merriment once more which lasts until Sunday evening. They bring the bride’s dowry chest and her clothes from her parent’s home with other minor gifts that will be distributed among the groom’s people.

The wedding celebrations end on the Monday. From the time that they received Holy Communion during the wedding service and for eight days, the bride and groom are not permitted to be together, the groom staying at the godfather’s house, where celebrations continue. If someone, by mistake, calls the bridegroom by his name, rather than ‘king’, they are fined, having to provide a sheep, which becomes the opportunity for more celebration.

After eight days, the priest comes to the newly-married couple’s house and, according to church law, takes away the censer and cross, explains the sacrament of marriage, gives them advice and reads a prayer of protection for them.

40 days after the honeymoon period of one month, the bride visits her parents’ home. This is known as tarts (return). It is the responsibility of the priest’s wife to bring her back to her husband’s home after 15 days.

The daughter-in-law in Zeytun is humble, docile and obedient towards her family, never speaking to her mother-in-law or father-in-law; the husband never speaks to his mother-in-law or father-in-law until the birth of the first child. [17]

Birth and baptism

Taking the newly-born infant, the midwife, after washing it, sprinkles it with salt and lays it to one side for a few hours. The mother asks that it be sprinkled with plenty of salt, so that the child will be firm and strong. There is a saying in Zeytun regarding people who speak improperly: ‘The midwife only sprinkled a little salt on him when he was born.’ The midwife comes to repeat this for eight days. When she leaves, she is given a cloth head-covering, apricot sheets, walnuts, raisins, wheat, cracked wheat etc as gifts.

When relatives and neighbours visit the new mother, they bring hapusa (a locally made sweet) with them so that she recovers her strength and has plenty of milk. Then she must remain in the house for 40 days. [18]

It is the midwife’s responsibility to inform the godfather and the priest on the day the infant is born, so that they will be ready to baptize the child eight days later. If the new-born is a boy, the godfather becomes very happy, saying, ‘Oh! We have gained another chakhmokh (musket)!’ He advises the midwife to sprinkle plenty of salt on the newborn so that when the child starts running about, he shouldn’t get too hot under the arms or in the groin, and that he will be firm and brave when he has to fight. Then he goes to church, makes confession, has Holy Communion and sleeps apart from his wife for 8 days. He buys a special material used for baptisms called gongugh for the baby; if it is a boy, 1.5 gankuns (a measure from the tip of the middle finger to the inside of the elbow, or about 2 feet, 60 cm) of silk, and if it is a girl, the same length of multi-coloured woven material printed with flowers.

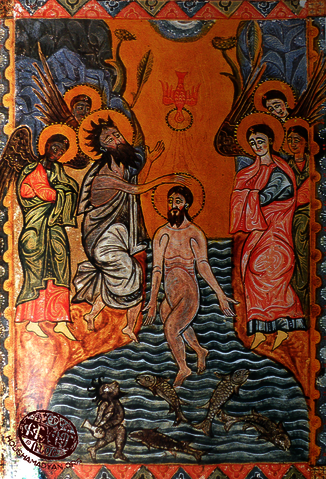

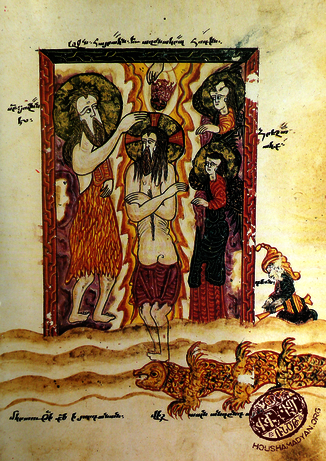

The baptism of a boy is accompanied by a solemn Mass and madagh. On the chosen day the godfather, carrying the infant comes to the church and waits for the priest. A boy brings a bucket of water. The midwife undresses the infant and hands him to the godfather. He and the priest take the child to the font and christen him in accordance with rites of the church. The women ask the midwife for a little of the water in the font to bring home with them. After the ceremony the godfather, carrying the infant, with a pair of lighted candles and with the priest and deacons, all come to the baptized child’s home. The new mother will be seated, covered in a white bridal sheet. The godfather puts the child on a cushion in front of the mother, saying, ‘May he grow up with a mother and father.’ In her turn she bends and kisses the godfather’s foot. After the priest’s blessing, the house owner invites everyone to the table, for a baptism meal. The godmother gives the godfather a gift of a handkerchief, apricot sheets, raisins and a bunch of flowers. The godfather pays the expenses of the baptism – for the priest, the church and the midwife’s fee, the material and the coloured thread that the baptismal cross is threaded on. [19]

After keeping the Holy Chrism on the child’s body for eight days, the midwife comes to bathe the child. Those present throw coins into the basin; these are the gift to her.

40 days later the mother, taking the infant, goes to the church so that the priest, through a special ceremony, ends the child’s 40 day seclusion. It is also a mandatory custom to take the child, with walnuts and raisins, to the church on the first feast of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (Diyarnentarach) for a blessing.

On every feast day the godmother sends the godfather a gift parcel containing a bottle of oghi or wine, several kinds of fruit, a dish of soup, a shirt or a buckle and or a handkerchief. [20]

Baptism

1 Gospel, Harput, 1025 (Source: Adriano Alpago Novello, Dir Armenier. Brücke zwischen Abendland und Orient, Stuttgart/Zürich)

2 Gospel, Klatsor, 1307 (Source: Adriano Alpago Novello, Dir Armenier. Brücke zwischen Abendland und Orient, Stuttgart/Zürich)

3 Gospel, Avants, Vasburagan, 1600. Painting by Zakarya Avantsi, Ms. 2804, f. 12 v, Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts - Matenadaran, Yerevan (Source: Tamara Mazaéva, Hratchia Tamrazyan (editors), La miniature arménienne, Ed. Naïri, Erevan, 2006)

Death and burial customs

If there is a sick person near death, the priest is called so that the person’s confession may be heard and Holy Communion administered. It is considered to be a great sin or very bad luck for someone to die without having taken Communion. This ceremony is called idemide beshor (final provision). At the time of death those present try to quickly close the deceased’s eyes and mouth and cross his hands over his chest, and to align the body towards the east. Then they call the priest so that he can say a bidding-prayer (hokots), then the body is put on a wide board to one side in the house to be washed with hot water and soap. The fire used to heat the water is immediately extinguished and its remains are taken and thrown far away (so that no one picks them up by mistake and takes them to their house, thus becoming the reason for a death in the family). [21]

The body is shrouded in an unwashed cloth seven gankuns (about 10 feet 6 inches, 3m) long. If the deceased person is a woman, then women must prepare the body and sew the shroud; if it is a man, then men must do so. When the shroud is being sewn, a piece of communion wafer is put in the deceased’s mouth and incense and a candle brought from Jerusalem in the palms of the hands. They put a khedug chuangen (a red, worked silk string brought from Jerusalem used both at baptisms and funerals) about the deceased’s neck. [22] Then the priest and deacon arrive; they conduct a special ceremony in the house. Then, putting the body on a leshped (a litter used in place of a coffin), they cover it with an old cope and, singing canticles, take it to the church. If the deceased was wealthy, then on the following day they have a funeral service and burial after Mass; if not, they conduct the funeral service on the same day. With the relatives of the deceased gathered around the body, the priest begins the ceremony saying, in the place of the departed, ‘Alas, oh most holy...’ [23] Everyone from the same quarter of the town, without exception, attends the funeral. The litter is placed on the shoulders of four men and taken to the cemetery. On the way, female relatives of the deceased, each with a piece his or her clothing in their hands, loudly sing the praises of the deceased, crying and wailing. This custom is universal, except when fighters have been martyred in battle, when crying aloud is forbidden, it being considered to be unseemly and a curse on the martyr. In the evening all the people from the quarter, the priest and the ishkhan (the notables are called by this title) go together to the departed’s home to commiserate with and comfort his or her relatives. A spirit meal (hokedjash) is given only to the priests and the poor. On the following day they all go together to the cemetery for the Aykuts (Daybreak) ceremony, and a huge spirit meal is served, made by the deceased’s relatives and neighbours. If, however, the weather is not good, then it is served in the deceased’s house.

There is another custom associated with burials: when women who have gone to get water hear that a death has occurred, they pour the water away and return to the fountains to refill their pitchers as a sign that they share the deceased’s family’s grief.

A priest’s funeral differs from an ordinary one, in the sense that first, the church bell is sounded sadly for a long time then his body is taken there, where it is washed and kept, with candles burning around it, until dawn the next day. After morning Mass, the last rites are administered by the abbot of the local monastery. The inhabitants of all the quarters of Zeytun come to pay their last respects. The deceased’s clothes are sent to the monastery. The cost of the death meal is paid for by the deceased’s blessing godfather. [24]

Another belief is that when the person dying gives up the ghost with difficulty and any member of the family is absent, the relatives are advised by those close by to bring something belonging to the absentee near to the person dying. [25]

The deceased’s new clothes are given to the priest and the old ones distributed. It is also the custom to give the priest a tray and a spoon as his death portion. The people of Zeytun don’t grieve; they can even marry the following week.

- [1] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present, Part 2, Paris, 1903, p. 135. [In Armenian]

- [2] K. Deovlet, Sandokh, Paris, 1945, p. 99. [In Armenian]

- [3] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun, Istanbul, 1884, pp. 72-75. [In Armenian]

- [4] Ibid, pp. 75-77:

- [5] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 136.

- [6] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 78.

- [7] Ibid, p. 80.

- [8] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 137.

- [9] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 83.

- [10] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 138.

- [11] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 84.

- [12] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 140.

- [13] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 86.

- [14] Ibid, էջ 88:

- [15] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 141.

- [16] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 88.

- [17] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, pp. 143-147.

- [18] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 18.

- [19] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 134.

- [20] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 21.

- [21] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, p. 148.

- [22] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 98.

- [23] Ibid, p. 99.

- [24] Zeytuntsi, From Zeytun’s past and present …, pp. 147-150.

- [25] H. Allahverdian, Ulnia or Zeytun …, p. 97.