Kaza of Bulanik - Geography

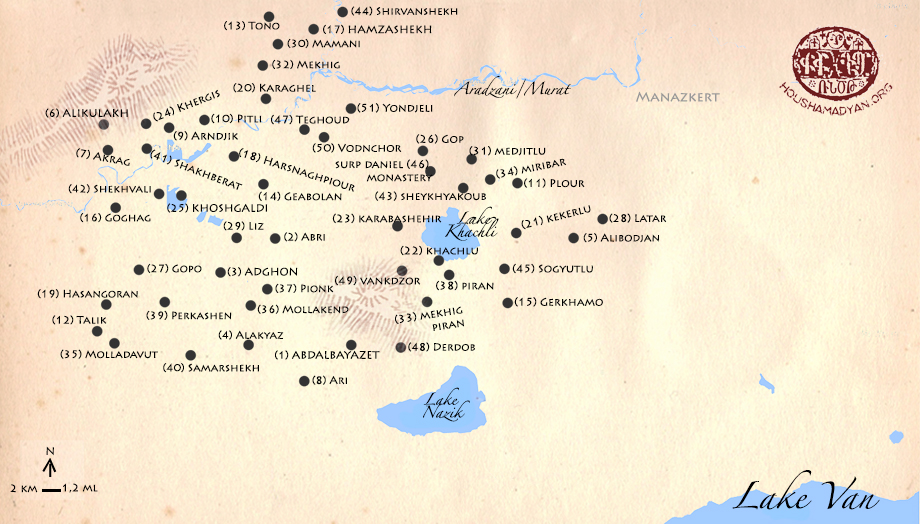

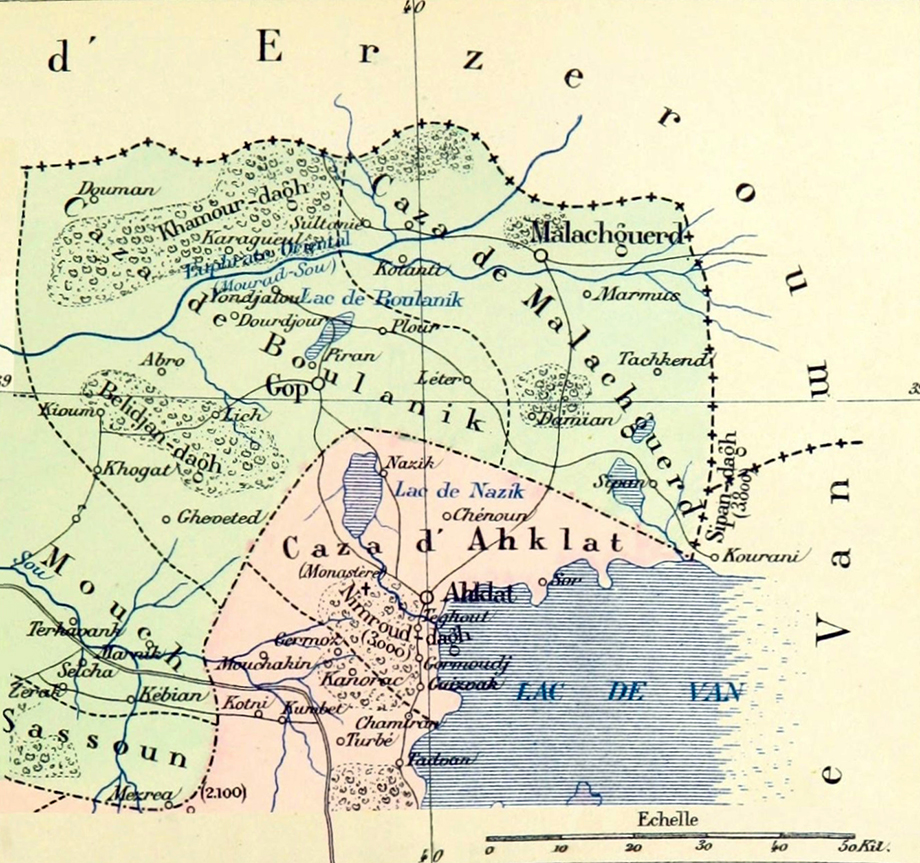

During the late Ottoman period, the kaza of Bulanik was a county in the Moush sandjak (prefecture) of the vilayet (province) of Bitlis (Baghesh) and was known as one of the greatest grain-growing counties in all of the Armenian Highlands. Bulanik, also pronounced Bulanekh, Bulanukh or Bulanegh, derives its name from a Turkish word meaning “muddy,” “turbid,” possibly because of the black soil that once covered most of the county. [1] The county’s historical Armenian name is Hark. A gavar (county) of the Tourouberan ashkhar (province) in the Kingdom of Greater Armenia from the fourth century BC to the fifth century AD, Hark apparently occupied a larger area, which included three adjacent counties from the province: Abahounik, Khorkhorounik, and Bznounik. [2] Throughout the early- and late medieval period and during the Ottoman era following it, the territory of Bulanik overlapped that of Hark and parts of Khorkhorounik counties of the ancient Armenian kingdom. [3]

The kaza of Bulanik was situated in the northeastern section of Moush, sloping away from the northern border heights of the Plain of Moush to the Aratsani (Murat) River and the opposite heights of the mountain ridge of Khamour. [4] In the east and northeast, Bulanik bordered the kaza of Manazkert, another county of the Moush sandjak. In the northwest, it bordered the kaza of Khnous of the Erzurum province. In the southeast, the county bordered the kaza of Khlat of the Bitlis province along the Bznouniats mountain-range, with Mount Sipan (Nekh Masik or Süphan Dağı) as the highest peak. In the west and southwest, Bulanik bordered the kazas of Varto and Moush, two other counties of the Moush sandjak. The length of the kaza of Bulanik was estimated at about sixty-one kilometers (thirty-eight miles) and its width was about twenty-four kilometers (fifteen miles). [5] The principal town of the county was Kop, a locality situated northeast of Biledjan Mountain and north of Lake Khachli (Haçlı Gölü), on the left bank of the Kor-djour River (Güllüce or Körsu Deresi), 78 kilometers (49 miles) northeast of Moush on the road leading from Moush to Manazkert.

The terrain of Bulanik consists primarily of vast stretches of nearly level land and, to a lesser extent, of mountain ranges and barrows. The terrain in the northwestern and western sections of Bulanik was is mostly mountainous. The radial mountain mass of Biledjan divided the kaza of Bulanik into a western and eastern territory or, administratively, into Upper and Lower sub-districts, called nahiyes. While vast tracts of lowlands covered both nahiyes, those in Upper Bulanik spread farther and wider compared to those in Lower Bulanik, because they were largely formed by the Aratsani River. [6] Most Armenian villages were surrounded by meadows and crop fields in a picturesque, lightly forested landscape where only willows and poplars grew. [7] As a result, the villagers used pressed dung as fuel. [8] Bulanik Armenians’ geographical situation was advantageous compared to that of the Turks and the Kurds. The Armenian population extended across the Armenian Highlands from east to west in varying levels of density. In Moush, the crowded Armenians created a wedge dividing two branches of the Muslim inhabitants. [9]

The highest peak in the mountainous areas of Bulanik was is the rugged mass of Biledjan (Bilican Dağları) which rose to a sharp-edged ridge at an elevation of about 2,743 meters (9,000 feet), according to one source, [10] or about 2,950 meters (9,678 feet), according to another. Biledjan stretches from south to northeast in between lakes Nazik and Khachli—to the west of them, and together with nearby mounts Sarakn (Nemrut or Nemrut Dağı) and Nekh Masik (Sipan) formed a triangle, which earned it the name “Sipani net,” in Armenian, “Sipan’s arrow.” [11] The massif has several extensive slopes and peaks, the highest of which bore the same name. Other peaks were called Douman, Berdi sar, Shekh-is, Djodj Hayat, Poqr Hayat, Khandzar, Kosa sar, Kalvakar, Djrovloro sar, Djodj zhakhnots, and Shakar-boulagh. [12] Their Turkish names are Bilican Tepesi, Ziyaret Tepesi, Vangesor Tepesi, Avni Kalesi Tepesi, Şeyhtokum Tepesi, Karaburun Tepesi, and Hasan Tepesi. It does not seem possible to ascertain which peak in Turkish corresponds to the one in Armenian. In the past, Biledjan was more heavily forested, with a grove called Egestar (Turkified from the Armenian Aygestan, meaning “vineyard”) on one of its slopes. [13]

One tradition links the massif’s name to Bel, the ruler of Babylon, who was slain in the rage of a battle by Hayk Nahapet, the progenitor of the Armenian nation, with a shot using a long bow. Bel’s corpse was burned atop the mountain, thus “Bel+a+djan,” in Armenian “Bel’s body.” This version is supported by the massif’s alternate name, Gerezmank, in Armenian, “grave,” “tomb”. However, a local folktale had it that the massif was named after a king by the name of Bedjan, whose fiefdom extended near the slopes of the mountain. Yet another theory suggested the massif could be named for a breeze that blew from its slopes, which Armenian residents of Prkhous, a village in the neighboring Khlat county, called “bledj.” According to the grammatical rules of the Kurdish and Persian languages, bledj could be a designation of the word “bledj+an” in the singular. [14]

Khoylibaba, second to Biledjan in terms of elevation, is a peninsular forest-clad mountain situated in the middle of a triangle formed by the Khnous county, the Khandrez nahiye of the Moush sandjak, and the Lower Bulanik nahiye. The mountain, also pronounced Kolibaba, rose between Bilejan Mountain and the mountain ridge of Khamour.

The Khamour ridge was joined on to the section of a great block of elevated land whose eastern wall projected some distance towards the south, almost up to the right bank of Aratsani. The deep valley, which was formed by this projection and by the ridge of Khamour, is filled by the lofty pile of Khoylibaba that stretched from southwest to northeast, only connected beyond an extensive depression with the slopes of the main ridge. [15]

A portion of that section of block of elevated land is known as the Zernak mountain-range. The Zernak Mountains stretches from north to south and rose to a considerable elevation east of Khamour before descending to the valley of the Pyurakn River (Bingöl Su). [16]

In the southwestern edge of Lower Bulanik rises the Kosour mountain-range, which stretches from Charbohar, a right-bank tributary of the Aratsani River, and connected with the Plain of Moush, thus becoming a natural barrier that separated two counties within the Moush sandjak: Bulanik and Moush.

In the southeastern section of Upper Bulanik, near the Kekerlu village, were unnamed rocky hillocks, called “kerner” or “kraner” in the local parlance.

There were also several ravines and passes in Bulanik which served as through-passages to the neighboring counties. These were: in the southwestern part, the Zatkha-getuk pass; in the southern edge of Lower Bulanik, the Kela-rashu gorge; in the southern edge of Upper Bulanik, the Kersa-getuk gorge that allowed passage to the Moush and Khlat counties; and the Zernaka track that led northward to the Khnous county. [17]

The most extensive plain in Bulanik, which bore the same name, included some of the most fertile land in all of the Armenian Plateau, whose soil yielded grain of excellent quality. [18] In addition to wheat, the Plain of Bulanik produced a particularly good variety of barley and millet. [19] The plain extended in length from the Dutagh village southwestward to the Teghout village for sixty-nine kilometers (forty-three miles), and in width, from the eastern reaches of the Khnous River to the Khachlu village for twenty-six kilometers (sixteen miles). In the northeast, the beginning of the plain was considered part of the Aratsani River valley near the Dugnuk village, north of Manazkert. In the southwest, the plain was separated from the Plain of Moush by the Liz barrows. In the southeast, Mount Sipan separated the plain from Lake Van. In the west, the plain reached across the mountain mass of Biledjan and its outliers to another extensive stretch of fairly level ground. The plain’s median part was formed from the confluence of the Aratsani River and rivers Meghraget, Badnots, and Khnous.

Other lowlands of Bulanik included the following plains.

Beginning from the east shore of Lake Khachli and extending eastwards to the Kekerlu village laid the Khazana plain, which took its name from one of the names by which the lake was known - Khazan.

Near Kop there were plains and fertile tracks of level ground covered with silt, called “hakon” in the local parlance, which bore the names Adji Su, Shorer, Bastovar, Alis, and Shamb. These were extensive stretches of the Oshakan or Havtrang (translated from Kurdish as “seven colors”) valley, which extended westward along the banks of the Aratsani River from as far as Alashkert, with which the Plain of Bulanik was connected via the Glych-getuk pass. In Bulanik, these hakons stretched from Manazkert to the root of the Zernak Mountains, continuing beyond the county along the banks of Charbohar into the Plain of Moush.

In Lower Bulanik there was an orchard called Kopo near the town of Liz and a flat plain near the Shakhberat village. An unnamed small plain lay near the Goghag village.

Water abounded in Bulanik; numerous rivers coursed down the county’s plains.

The largest, for which it earned name of the mother-river of the Armenian Highlands, was Aratsani, also known as Murat Nehri or Eastern Euphrates. Aratsani originated near the Tsaghkants Mountains (Aladağ) and flowed into a gorge north of Mount Tondrak, near the Diyadin village. Here, from funnel-shaped pits along its banks, warm sulfur springs erupted, which in antiquity were known as “Varshaki djermukner,” purportedly named so after Varhsak, a brother of the Armenian nobleman Sahak II Bagratuni. After flowing westward through Manazkert and Bulanik, where it adjoined the Khnous River near the Shirvanshekh village, into the Plain of Moush, where it adjoined the Meghraget River (Karasu), Aratsani met the Euphrates. [20] The locals did not use waters of the river for irrigation purposes, but reaped the fruits of the fertile soil in the valleys and grassy plains that stretched along its banks. The Khnous River and its tributaries, as well as numerous other rivers and streams, were drawn on for irrigation.

One such stream stemmed from the north shore of Lake Khachli and was known as Kor-djour. According to one source, Kor-djour took its name from an Armenian word meaning “blind,” “impure,” because of its turbid waters. [21] Other source suggests that the stream’s original name, Koro-dzor, derives from Kori, a county in the ancient Touruberan province. [22] Although Kor-djour was a shallow stream, its waters formed hakons along the banks and were vital to the villagers as they irrigated crop fields and powered water mills. Flowing near the Sheykhyakoub village and Kop, the stream winded westward and ultimately joined the Aratsani River as its left-bank tributary.

Another stream, Beroush (Beruş Deresi), stemmed from the south shore of Lake Khachli and flowed through the Piran village.

The Sev-djour stream rose in Gonklik, a barrow that stood north of Bilejan Mountain and southwest of Kop. The stream then disgorged its waters into Kor-djour. Previously, Sev-djour reached Alis, a fine-soil plain near Kop, and formed a rushy bog there. Over time, the bog dried up and turned into a vast meadow.

Lza-get, also known as Vard or Lza-djour (Mollokent Deresi), was a left-bank tributary of Aratsani River. The river originated in an area northwest of Lake Van, out of the wells that sprang up on the western slopes of Bilejan Mountain near Pionk and Mollakend villages. Flowing westward through Lower Bulanik, Lza-get irrigated fields and powered water mills, before merging with the Aratsani River near the Akrag village.

There were two lakes in Bulanik: Lake Khachli, essentially a lakelet, which covered ten square kilometers (four square miles) and a maximum depth of seven meters (twenty-three feet), and Lake Nazik which covered forty-four square kilometers (seventeen square miles) and a maximum depth of about fifty meters (one hundred and sixty-four feet). Lake Khachli’s elevation was less than that of Lake Nazik, at 1,692 meters (5,550 feet). Lake Nazik’s elevation was 1,876 meters (6,155 feet).

Lake Khachli was loaded with dark sedimentary matter, a characteristic which inspired one of the names by which the lake was known, Bulama, or the “muddy lake.” [23] The lake was also known by the names Khachi, Khachan, Khachlva, Kazan or Khazana, and Bulanik proper. Kurds called the lake Gola Shelo, [24] a derivative of Shailu, an Assyrian name, by which English archeologist Austen Henry Layard referred to the lake in the mid-nineteenth century. [25] The lake was nearly circular in shape, three to four kilometers (two to three miles) in diameter; its color was muddy brown, emanating a fetid and nauseating odor from the fermentation of vegetable matter. [26] The water in this cliff-rimmed lake tasted sweet and fish abound. The lake had two holms, covered with a thick layer of bird droppings, giving them a tinge of lime. Khachli could appropriately be called the “Nile of Upper Bulanik,” as waters emerging from it via two streams irrigated the nearby crop fields. The ground adjacent to Lake Khachli was level on the east and south. To the west and north, lower elevations of Bilejan Mountain descended to the lake shore. [27]

According to legend, Khachli was a mysterious lake; its waters inhabited by fiery horses and buffalos. Buffalos were said to occasionally emerge from the waters and impregnated cows, which produced snow-white offspring. Another legend has it that in Latar, a village near the lake’s western shore, stood the palace of idolater king Prosh. [28] Unspecified other sources indicated that the palace stood in a small fortress called by its Kurdish name Kela Hoshk, the ruins of which could be found near the lake’s northern shore, northwest of the Saint Daniel (Surb Daniel) monastery at Kop. [29] Before passing away, the king decided his steel sword, “havlooni toor” in Armenian, should be thrown into the lake. His intention was to prevent strife among his three sons. The king ordered each in turn to carry out his wish. The eldest and the middle sons, one after another, took hold of the sword, then lied to their father that they had immersed it in the lake. But their deceit was exposed. Only the youngest fulfilled his father’s command and related that after the sword had gone under, the lake billowed, its waters turned turbid, and loud sounds resonated from its depths.

According to the legend, bravehearts ruled the bottom of that lake, and mightiest of these had claimed the sword, placing it under his head and keeping a firm grip on it. In response, other bravehearts marched against him every week, fighting to strip him of the magic sword. These battles caused the lake to billow, its waters to turn turbid, and brattle sounds to rise from its depths. The king predicted that when the lake dried out, the winner of the scuffle among the bravehearts would emerge, he would be the one holding the sword. [30] Near the western shore of Lake Khachli and at the northeastern root of Mount Bilejan stood an historic settlement, known as Kharabashehir during the Ottoman era. According to ancient chroniclers, it was founded by Hayk Nahapet after his exodus from Babylon into the land of Ararat. He founded a settlement in the plain northwest of Lake Van, giving it his name, Haykashen, meaning “built by Hayk.” [31]

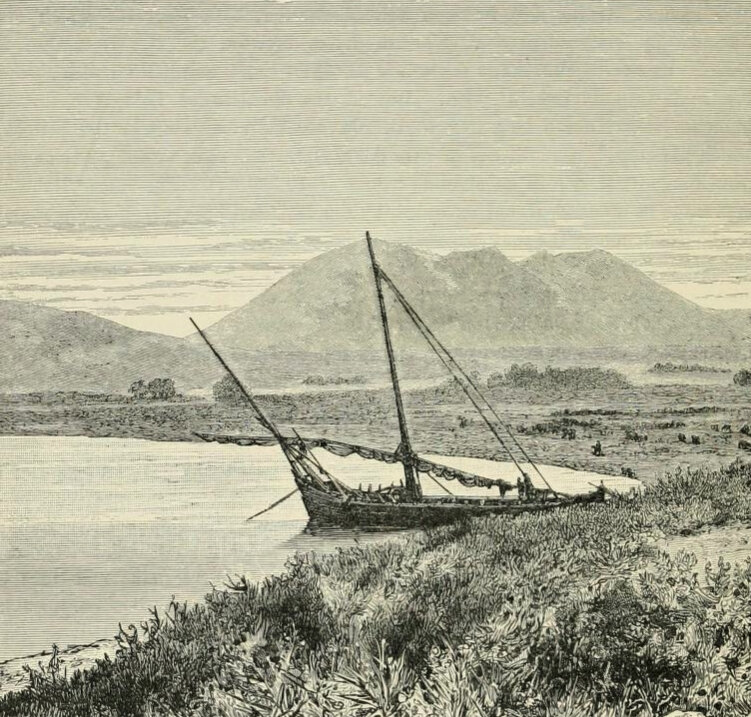

To the south of Lake Khachli lay Nazik, a freshwater lake, also called Nazuká lich. The lake almost certainly got its name from the Armenian word nazeli, which means “gentle,” “graceful.” The water in the lake was soft, clear, sweet, and therefore drinkable. Lake Nazik was oval in shape. There was a holm in the lake. Pelicans abounded on the lake, swimming singly over the mirror of waters or swooping above them in flight. [32] Fish was plentiful beneath its surface, consisting of a large stock of trout, delicious in taste. The fish were caught only at one period of the year, towards the end of May. The panorama offered by the lake and its environs was exceptionally picturesque. The whole landscape seemed infused with a calm and sweet air of romance. The smooth and quiet surface of the water reflected the outlines and varying tints of the surrounding landscape like a mirror. Five tributary streams supplied the lake, while its waters exited via two streams, one flowing to the Aratsani River near the town of Liz, and the other running into Lake Van near the Khlat village. [33] For a lakelet such as Nazik to send emissaries to a lake and river, [34] was a rare phenomenon. Water runoff from the lake continued until the early twentieth century; subsequently the runoff stopped, as a result of construction of roads and hydro-technical utilities.

Lakes Khachli and Nazik lent a touch of beauty to the dreary, yellow landscape of Bulanik, and charm came from Sipan, a snow-capped mountain located southeast of them, immediately north of Lake Van. Reaching 4,058 meters (13,314 feet), this dormant volcano, with a massive dome in the shape of a truncated cone, was the second highest peak in the Armenian Highlands after Mount Ararat (Masis). The slopes of the mountain were covered with Alpine meadows and showy, sweet-smelling flowers. Small, clear-watered lakes were at the base of the mountain. From the slopes of Mount Sipan, Bulanik locals could admire, on one side, the lovely view that the waters of Lake Van commanded, and, on the other, the beautiful landscape of the Bulanik and Manazkert counties.

The climate in Bulanik was moderate and conducive to good health, due to the mountainous terrain, as well as delicious well-water and fertile soil, sand-colored and moist, [35] or colored a rich brown wherever it was exposed by the plough in patches of cultivation. [36] Two rival winds blowing over Bulanik in different directions affected the local flora. One was the south westerly wind, which the Armenians called Msho qami, warm and dry, which would leave reddish coating on bread grains, slant the stems, and thin out the grains. The other one was Adjmu qami, a reviving and favorable wind that set from the Persian Gulf and, hauling around to Lake Van, would bring coolness and moisture to the crops.

Early winters brought neither freezing cold nor ground frost, but snow fell relentlessly, often reaching knee-deep. After the winter solstice, the weather turned cold and the ground froze․ Winters came early in Moush, generally in November, sometimes in October, lasting until mid-April. Bitter cold lasted for about forty dreary days. Ice sheets on Lake Khachli, as much as seventy-one centimeters (twenty-eight inches) thick, cracked, making rumbling noise that was heard for weeks in the far corners of the county. At nights heavy mist hung over the county until it cleared in the early dawn, when it drifted to the mountains. The winter brought blizzards or low level drifting snow, or a combination of both, and whirlwinds called satani qami and hurricanes soaring up to the sky. Subsequent northeasterly chilling breeze, called parzegh, cleared up the skies, presaging the coming of spring.

Spring brought milder, if undependable, weather. In March, the sky grew dim and the clouds darkened, leading to occasional rainfalls, which had no measurable effect on the deep snow cover. Gradually, aided by a warm southerly wind called harav qami, rainfalls softened the snow causing it to melt away. In eastern areas of the county, the climatic effect of Lake Van generated the fertile black soil․ Rainfalls intensified beginning from the mid-April, marking the real break out of winter into the revival of spring.

Summers were hot and torrid; sometimes fog thickened around the mountains. In the summertime Bulanik provided a bountiful harvest of manna, which appeared in the form of white grains or ice pellets on the broadleaved trees, such as ash or oak trees. Because manna tasted like sugared honey, Moush Armenians called it “Surb Karapet’s halva” (the halva of Saint John the Baptist). Also called “gazba” or “gazben,” manna is mentioned in the Bible as the food that God provided for the Israelites after their exodus from Egypt to help them walk through the Sinai desert to the Promised Land. [37]

In autumn, during the dry weather the ground covered with hoarfrost, which penetrated as deep as fifteen centimeters (six inches). However, most of the fall season was bitter cold because of frequent gusty winds accompanied by rain. Late autumn brought piercing northern winds called hyusis qami, which rose unexpectedly but moved on quickly.

- [1] Bensé. Bulanekh kam Hark gavar (Bulanik or Hark County), in Ethnographical Journal, volume 5. (Tiflis, 1899), p. 9. (in Armenian)

- [2] Hakobyan, Tadevos. Hayastani patmakan ashkharhagroutiun: Ourvagtser (Historical Geography of Armenia: The Outlines). (Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 2007), p. 159. (in Armenian)

- [3] Kévorkian, Raymond, and Paul Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du genocide (Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide). (Paris: ARHIS, 1992), p. 498.

- [4] Lynch, H.F.B. Armenia: Travels and Studies, volume 2: The Turkish Provinces. (London, New York: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1901), p. 345.

- [5] Bensé, op. cit., p. 11.

- [6] A-Do (Hovhannes Ter-Martirosian). Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzroumi Vilayetnere (The Provinces of Van, Bitlis and Erzerum). (Yerevan: Tparan Koultoura, 1912), p. 144. (in Armenian)

- [7] Mirakhorian, Manuel. Nkaragrakan oughevorutioun i hayabnak gavars Arevelian Tachkastani (A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions of Eastern Turkey). (Constantinople: Partizpanian Publishing House, 1885), volume 3, p. 67. (in Armenian)

- [8] Philippov, Vladimir N. Voennoe obozrenie Aziatskoi Turcii (A Military Review of Asiatic Turkey). (Saint Petersburg: A.E. Landau Publishing House, 1881), pp. 20-21. (in Russian)

- [9] Lynch, op. cit., p. 425.

- [10] A-Do, op. cit., p. 144.

- [11] Hakobyan, Tadevos, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan. Hayastani ev harakits shrjanneri teghanounneri bararan (Dictionary of Place Names of Armenia and Adjacent Territories), volume 1. (Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 1986), p. 702. (in Armenian)

- [12] Bensé, op. cit., p. 12.

- [13] Bensé (Sahak Movsissian). Hark (Msho Bulanekh) (Hark։ Bulanik County of Moush), in Armenian Ethnography and Folklore, volume 3. (Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Press, 1972), p. 33. (in Armenian)

- [14] Bensé. Bulanik or Hark, p. 12.

- [15] Lynch, op. cit., pp. 333, 350.

- [16] Ibid, 347.

- [17] Bensé. Bulanik or Hark, pp. 11, 13.

- [18] Lynch, op. cit., pp. 344-345.

- [19] Prothero, G.W. (ed.). Armenia and Kurdistan. (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1920), pp. 50, 65.

- [20] Avetissian, Kamsar. Hayrenagitakan Etiudner (Cross-cultural Notes on Armenia). (Yerevan: Sovetakan Grogh, 1979), p. 32. (in Armenian)

- [21] Bensé. Bulanik or Hark, p. 15.

- [22] Hakobyan et al., op. cit., volume 3, pp. 236-237.

- [23] Lynch, op. cit., p. 344.

- [24] Hambavaber, no. 25 (1916), p. 797.

- [25] Layard, Austen H. Discoveries among the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. (New York: Harpers & Brothers, 1853), pp. 16-17.

- [26] Oswald, Felix. A Treatise on the Geology of Armenia (Iona, Beeston, Nottinghamshire: Published by the author, 1906), pp. 175-176.

- [27] Lynch, op. cit., p. 343.

- [28] Bensé. Hark։ Bulanik County of Moush, p. 48.

- [29] Bensé. Bulanik or Hark, p. 14.

- [30] Srvandztiants, Garegin. “Hamov-Hotov” (With Taste and Aroma), volume 1, in Hye Gragetnerou Barekamner, (Friends of Armenian Literary Scholars, no. 16). (Paris: Araks Publishing House, 1949). pp. 83-85 (in Armenian)

- [31] Hakobyan et al., op. cit., volume 3, p. 339 and volume 2, p. 690.

- [32] Lynch, op. cit., pp. 323-324.

- [33] Millingen, Frederick. Wild Life among the Koords. (London: Hurst & Blackett Publishers, 1870), pp. 93-94.

- [34] Reclus, Élisée. The Universal Geography, volume 9: South-Western Asia. (London: J.S. Virtue & Co., 1891), p. 167.

- [35] Mirakhorian, op. cit., p. 67.

- [36] Lynch, op. cit., p. 258.

- [37] Serovbian, Sargis. “Tigranakertn u mananan” (Tigranakert and Manna), in Agos, March 9, 2015, www.agos.com.tr/am/hvotvadzi/10818/dikranagyerdn-u-mananan. (in Armenian)