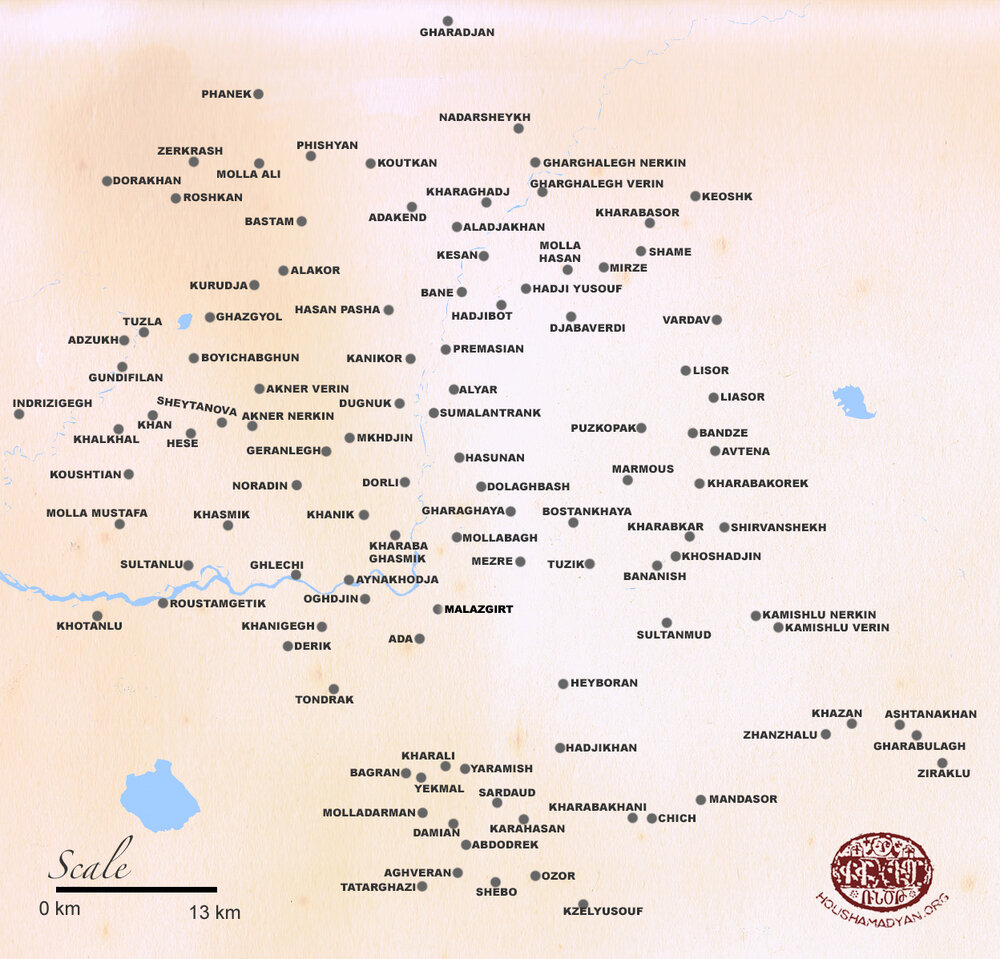

Kaza of Malazgirt - Monasteries, churches and places of pilgrimage

Author: Tigran Martirosyan, 30/05/2018 (Last modified: 30/05/2018)

A kaza (county) of the Moush sandjak (prefecture) of the vilayet (province) of Bitlis, Manazkert, later renamed Malazgirt, during the Ottoman era was the seat of a vice-prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church. From the fourth century BC and until the fifth century AD, the county’s principal town, Manazkert, was the administrative center of Apahunik, a gavar (county) of the Touruberan ashkhar (province) of the Kingdom of Greater Armenia. In the first half of the fourth century AD, King Khosrov II Kotak awarded the lands of the county to the Aghbianosians, a family of nakharars, members of the Armenian nobility. Aghbianosians turned Manazkert into episcopacy. [1] Because bishops serving in it figured in some chronicles as being affiliated with Apahunik, and in other chronicles with the neighboring gavar of Hark, it has been argued that both counties might have been under the jurisdiction of the same diocese. [2] Several bishops, who hailed from the Aghbianosian princely house and served in the Manazkert episcopacy, became catholicoi during the fourth and fifth centuries. These were Shahak I Manazkertsi, Zaven I Manazkertsi, Aspuraces I Manazkertsi, Melité I Manazkertsi, and Movses I Manazkertsi. [3]

From the fifth century onward, Manazkert had its own diocese, as testified by consecutive centuries of records of attendances at various ecumenical councils. One such council, a joint Armenian-Assyrian assembly, was convened in 726 in Norati (Noradin), a village situated fifteen kilometers (nine miles) northwest of Manazkert, to settle differences between the two eastern churches that arose from the teachings of anti-Chalcedonian theologians regarding the virgin birth of Jesus. The delegation of Armenian bishops and archimandrites was headed by Catholicos Hovhannes III Odznetsi. At that time Armenia was conquered by the Arabs, who turned the country into a province (in Armenian, ostikanate), with Armenian nakharars continuing to rule it as vassals of Arab amirs. Initially, the council was scheduled to be held at Artsn, a town near Karin (Erzrum), but the Arab governor forbade convening the meeting outside his domain, intending to exploit the alliance of the two largest Orthodox churches in Eastern Asia Minor against the Byzantine expansionist policies. [4] Almost three centuries later, Manazkert was annexed to the Byzantine empire.

In the ninth through eleventh centuries, Manazkert became the center stage of the Tondrakian religious movement, characterized by both Armenian and Byzantine church authorities as a heretical sect. The movement was centered on the area around Mount Tondrak, north of Lake Van. The votaries of the movement rejected the church hierarchy, supported property rights for the peasants and equality between men and women. On the other hand, the Tondrakians made a distinction between the God who created the material world and the God of Heaven who, they believed, alone should be venerated, considered Jesus Christ an angel, rejected the Old Testament, and denied the immortality of the soul and the afterlife. Having rocked the Armenian orthodoxy for almost two centuries, the movement was quelled during his tenure of Grigor Magistros, a Byzantine governor of Vaspourakan, Taron, Manazkert and other counties.

At the beginning of the eleventh century, the Byzantines had to confront the Seljuks, a nomadic Turkmen tribe belonging to the Oghuz branch of Turks, which migrated westwards from the steppes of Inner Asia a century earlier. The Seljuk intrusions, which lasted from the 1020s to the 1070s, brought chaos and were accompanied by killings and destruction of property. Those in Manazkert were the first to fall prey to the Seljuks when they entered the town after defeating an army of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes in 1071. In the decades that followed the battle, Turkic rulers and Muslim state-supported institutions expropriated the lands and properties of scores of Armenian churches in Manazkert. [5] Armenians had to rebuild the destroyed churches, and even enlarge some of them, one example outside Manazkert being the Saint Bartholomew (Surb Bardoughimeos) monastery near Aghbak (present-day Başkale), a town located southeast of Lake Van. [6]

John George Taylor, a British consul-general who travelled extensively in Armenian-populated regions of the Ottoman empire, reported in 1869 that in the vicinity of Manazkert, Bulanik, and Khlat (Akhlat) counties lived Kurds who belonged to the Hasananli (Hasanan) and Millanli (Milan) tribes. In Taylor’s words, the depredations of these tribes—encouraged by their chieftains and proceeds shared in by them—were manifest all around the area. Ruined Armenian churches, along with deserted villages and crumbling mosques, met the eye everywhere. [7] Thirty years later, Irish geographer Henry Lynch attributed the crumbling churches and towers of the fortress of Manazkert (in Armenian, Manazkerti midjnaberd) to the Muslim rulers of the town, and described them as “the melancholy landmarks of the progressive ruin of the Armenian inhabitants.” [8] The only well-preserved section of the fortress complex was the great tower in the citadel, which might have been later than the eleventh century. Still, in Lynch’s words, there could be “little doubt that the [repair and restoration] work was carried out by Armenians, and in harmony with the original plan.”

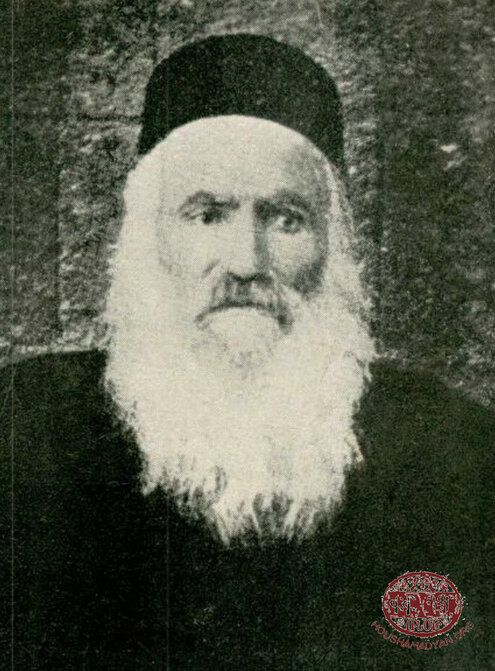

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, Manazkert churches and monasteries were under the jurisdiction of the Vandir or Saint Aghberik (Surb Aghberik or Aghberkavank) monastery located 103 kilometers (64 miles) southwest of Manazkert in the kaza of Khout-Brnashen of the Sassoun sandjak of the vilayet of Bitlis. [9] From then on, the vice-prelacy in Manazkert administratively reported to the prelacy in Moush located 102 kilometers (63 miles) southwest of Manazkert. The jurisdiction of the Moush prelacy extended over the counties belonging to the Moush and Gench (Genç) prefectures. [10] Immediately before the genocide, the prelate of Moush was Supreme archimandrite Vardan Hakobian. He succeeded Bishop Nerses Kharakhanian, who died on April the tenth, 1915, and did not witness the annihilation of his people [11] that started fourteen days later. In 1907, as the abbot of the Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) monastery, Father Vardan sent an entreaty to Czar Nicholas II. In it, the desperate cleric pleaded the Russian monarch to help free the Armenian populations of Manazkert, Bulanik, Moush, and Sassoun from the yoke of Turkish and Kurdish oppressors and establish a Russian consulate in Moush as a measure to safeguard Armenian lives. [12] Supreme archimandrite Vardan Hakobian shared the fate of tens of thousands Armenians of Moush, who were subjected to forcible deportation and murder during the genocide. He was beaten to death with crosiers in a Turkish prison somewhere near the town of Moush.

1) Supreme archimandrite Vardan Hakobian, the last clerical leader of Moush (Source: Hamazasp Voskian, Taron-Touruberani vankere (The Taron-Touruberan Monasteries), Vienna, 1953).

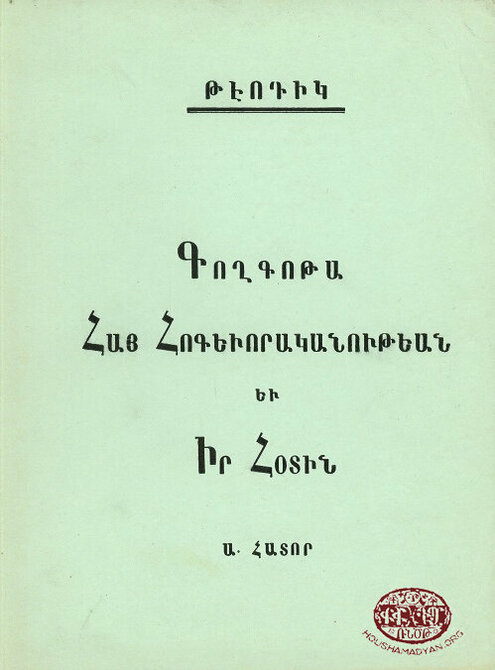

2) The title page of Teodik's book "Koghkota Trqahye Hogevorakanoutyan yev ir Hotin Aghetali 1915 Tariin" (The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915), Tehran, 2014 (reissue).

In the years before the genocide, the vice-prelate of Manazkert was Pastor Hovhannes Ter-Avetissian, a native of Noradin. In April of 1915, a group of Armenian men from the Van province managed to flee to Kzelyusouf, a village in the Manazkert county, but were killed by the Turkish gendarmes there. As soon as the crime became known, Father Hovhannes voiced his indignation to Ibrahim Khalil, the district governor (in Turkish, kaymakam) of Manazkert. [13] When the Russian forces arrived at Manazkert in mid-May, Father Hovhannes mingled with the crowds of Armenians fleeing from Ottoman troops and managed to survive the massacres the troops committed as they advanced.

Prior to World War I, according to the 1913 Patriarchate census, the number of Armenian churches and monasteries in Manazkert, both undamaged and dilapidated, was estimated to be 70. [14] True to their practice of decreasing the number of the Armenian population in Moush, local Ottoman authorities did not hesitate to decrease the number of Armenian churches as well. During his short sojourn in Moush in the late-1890s, Lynch related an incident of bullying a young Armenian priest and pressuring him to lower a real figure in order to portray the Armenian presence in the prefecture as puny as possible. When in the presence of an Ottoman commissary the priest was asked how many churches there might be in Moush, he answered, seven, which in and of itself already was an underreporting, possibly out of fear of the consequences. The commissary, however, had said four. After an armed guard escorting the commissary addressed the priest in Kurdish, “the poor fellow,” in Lynch’s words, “turned pale, and remarked that he was mistaken in saying seven; there could not be more than four.” Such was one of a few of Lynch’s experiences in Moush where, according to him, “the most abject terror was in the air.” [15]

Within a century after the genocide, all Armenian churches and monasteries in Manazkert, along with chapels, miniature chapel-like tempiettos (in Armenian, taghavarikner), cemeteries, and carved cross-stones khachkars, were completely destroyed. As of 1975, khachkars and tombstone remains at Alyar, church and khachkar remains at Noradin, and khachkars at Sultanmud still stood near these villages.

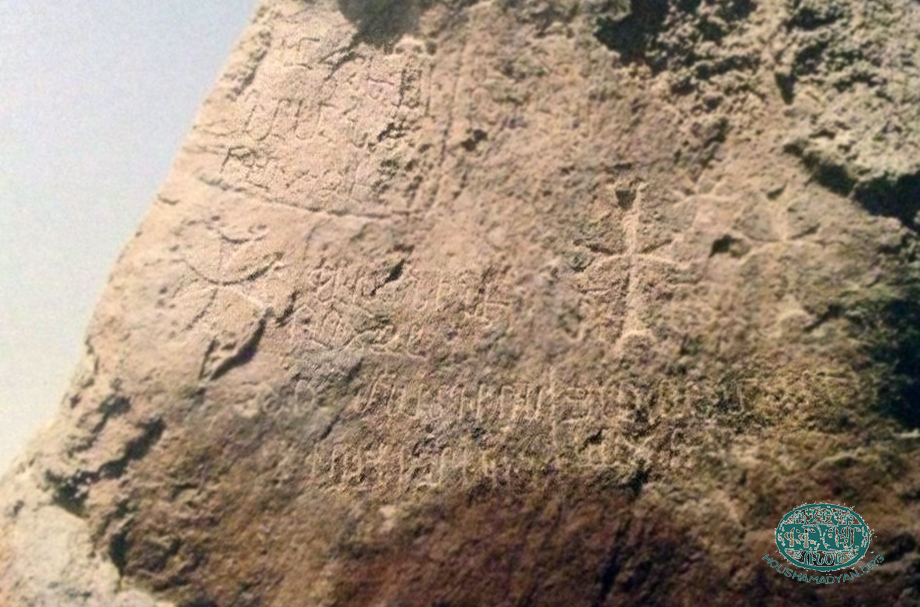

Carved crosses on tombstones at Bostankhaya and carved crosses with donation inscriptions on a rock at Dolaghbash remained visible. [16] In the photograph below, taken in 2007, Armenian inscriptions on the rock at Dolaghbash were already effaced.

As of 2014, one oxygonal, cradle-like tombstone lay in the Manazkert fortress. The tombstone, which apparently was brought from a nearby cemetery, dated back to the sixteenth or seventeenth century and bore a half-desecrated cross on one side and Armenian inscriptions on two other sides.

A rock bearing carved crosses and an inscription “cross [was] elevated” (in Armenian, kanknecav khaches) was found near the southeastern quarter of Oghdjin (present-day Okçuhan), [17] a formerly Armenian-inhabited village situated five kilometers (three miles) west of Manazkert.

This study relied on a number of sources which, along with the names of the most revered Christian saints in Manazkert and adjacent counties, can be found in the article “Kaza of Bulanik - Monasteries, churches, and places of pilgrimage” (http://www.houshamadyan.org/en/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-bitlispaghesh/kaza-of-bulanik/religion/churches.html). The 1878 travel guide by Armenian ethnographer Aristakes Ter-Sargsents (Tevkants) [18] and the 1902 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census of the population of towns and villages on the Plain of Moush and its vicinity collected by writer Gegham Ter-Karapetian, provided supplementary data. One important source is the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople’s lists of churches and monasteries by village for the Moush sandjak submitted to the Ottoman ministry of justice and religious minorities in 1912 to 1913. For unknown reason, however, the lists left out Manazkert and three other counties of the prefecture: Bulanik, Vardo, and Sassoun, thus restricting the count to 82 monasteries and churches in the town of Moush and the villages of the Plain of Moush. [19]

Below is a list of monasteries, churches, and places of pilgrimage in the kaza of Malazgirt during the Ottoman era. Wherever possible, the list includes information regarding the number of the serving clergy, which was extracted from the last of a three-volume travel guide published in 1885 by ethnographer Manuel Mirakhorian, as well as the names of the clergymen, which were obtained from the 1902 Patriarchate census data collected by Ter-Karapetian. Unless otherwise mentioned, the information submitted below is drawn from sources covering a period of about thirty years or from the mid-1880s to 1915.

Monasteries of the Malazgirt county

Monasteries and convents, both undamaged and dilapidated, were abundant in the Malazgirt county. In the medieval era, some monasteries in the county evolved to become major centers of arts and sciences on a par with large populated areas. Besides being the sites where monks lived under religious vows, some monasteries were considered sanctuaries by the locals. Others, such as the convent at Gumbayt, a village in the Apahunik gavar, and monasteries at Arsé (Hesé) and Tondrak, housed scriptoriums, [20] writing rooms that were set aside for the use of scribes, typically monks themselves, engaged in storing and copying manuscripts. The 1902 Patriarchate census of the population of towns and villages on the Plain of Moush and its vicinity listed around eleven monasteries. [21] The 1913 Patriarchate census listed around 37 monasteries. Raymond Kévorkian and Paul Paboudjian, authors of the treatise “Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide,” raised the figure to 45, using supplementary Patriarchate census data available to them.

Aladjakhan

One unnamed dilapidated monastery. The ruins of this formerly large structure stood on a barrow near the northern quarter of the village.

Aynakhodja

Two unnamed dilapidated monasteries. One of them stood near the northern quarter of the village.

Derik

One unnamed dilapidated monastery. This monastery is not to be confused with the one that stood in the homonymous Armenian-inhabited locality in Moush county (present-day Yücetepe), situated 27 kilometers (seventeen miles) north of the city of Moush at the site of the historical village of Ashtishat.

Dolaghbash

Two dilapidated monasteries, Tsartpov vank and Karmir vank.

Gharaghaya

Two unnamed dilapidated monasteries.

Hasan Pasha

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Hesé

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Kanikor

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Khangar monastery (Khangar or Khangari vank) at Akner

The monastery stood not far from the village and by the late eighteenth century was in a dilapidated state. There were, in fact, two Akner villages, Upper and Lower. However, sources used for this study did not indicate which of these two villages Khangari vank was closer to.

Khanigegh

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Kharaba Ghasmik

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Marmous

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Mollabagh

Two unnamed dilapidated monasteries.

The Monastery of Saint George (Surb Gevorg) at Bostankhaya

The monastery became dilapidated by the early twentieth century. Some sources identify Surb Gevorg as a church.

The Monastery of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis) at Dugnuk

There were, in fact, two monasteries bearing the same name. One was located east of the village. The other one stood north of the village.

The Monastery of Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) at Karadjan

Formerly an intact domed structure known by the name of Surb Astvatsatsin, the monastery by the late nineteenth century fell into disrepair figuring as an unnamed monastery in most sources.

The Monastery of Saint John Chrysostom (Surb Hovnan Voskeberan) at Khotanlu

Tevkants reported that by the mid-nineteenth century Surb Hovnan Voskeberan was a dilapidated monastery.

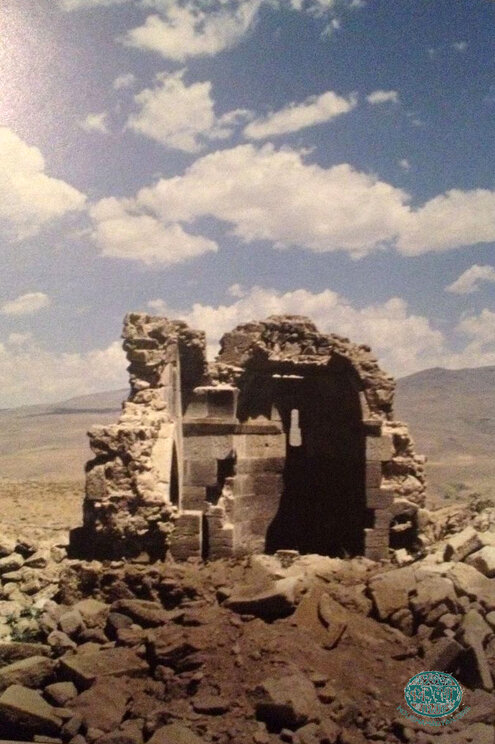

The Monastery of Saint Nicholas of Apahunik (Apahuniats Surb Nikoghayos) at Kurudja

Also called the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) monastery, Surb Nikoghayos was in a dilapidated state throughout the centuries before the genocide. By the early twentieth century, outer walls caved in, but the rest of the vaulted structure remained only half-ruined.

The Monastery of Saint Nerses (Surb Nerses) at Manazkert

Also called Saint Patriarch Nerses (Surb Nerses Hayrapet), the monastery stood a 15-minute walk from the town center. By the early twentieth century, the monastery shrunk considerably because of the destruction and was converted into a chapel with an area barely measuring three to four square meters. The foundation had sunk insomuch that visitors would bend down in order to enter the chapel.

The Monastery of Saint Gregory the Illuminator (Surb Grigor Lusavorich) at Manazkert

Among sources used for this study only the encyclopedic dictionary compiled by Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan listed Surb Grigor Lusavorich as another monastery that stood at Manazkert. [22]

The Monastery of Saint Daniel (Surb Daniel) at Manazkert

The monastery was situated at a short distance from Manazkert, east of the town. In the monastic graveyard stood beautifully carved khachkars, some dating back to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries or even earlier.

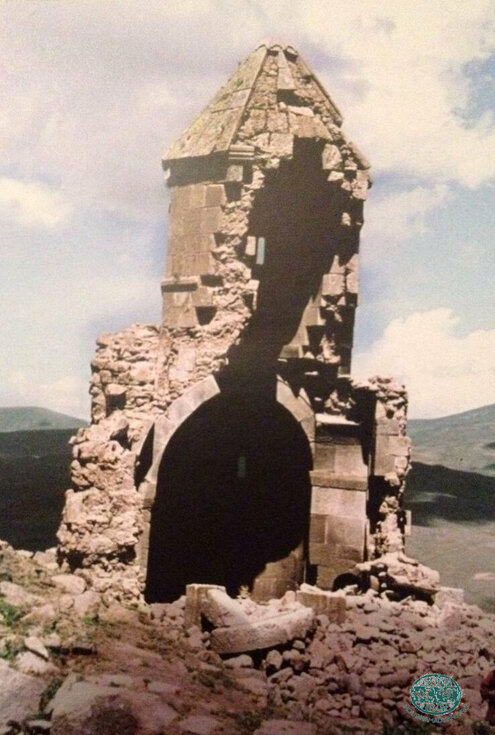

The Monastery of Saint Hovhannes Odznetsi (Surb Hovhannes Odznetsu vank) at Noradin

Also called the Hovhan Odznetsi monastery (Hovhan Odznetsu vank), Surb Hovhannes was located near Noradin, a village where in 726 an ecumenical council mentioned above was convened. In the large monastic graveyard stood khachkars complete with elaborate designs, some dating back to the thirteenth century, as well as several tombstones. [23] In the early twentieth century, ruins of the outer walls of the monastery still stood. The chapel that was erected on the site of the destroyed church reportedly remained intact until the 1920s.

The Monastery of Saint Hovhannes (Surb Hovhannes) at Tondrak

In the ninth century, Surb Hovhannes became a place of assembly of the Tondrakians. The monastery became dilapidated by the early twentieth century. The 1913 Patriarchate census listed two dilapidated monasteries in the village.

Roustamgetik

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Sultanlu

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Yekmal

One unnamed dilapidated monastery.

Churches of the Malazgirt county

In the late nineteenth century and prior to the genocide, there were more than a hundred Armenian or formerly Armenian-inhabited or mixed-population villages in the kaza of Malazgirt. Almost every Armenian village had a church; larger ones had two or more churches. There were also ruins of churches and chapels that stood especially to the west and south of the town of Manazkert, some named, but most unnamed. [24] Almost every functioning church had serving clergy. Ottoman salnames, government annuals containing statistical data for the state and provinces, stated that in 1871, 1872, and 1873 in the kaza of Malazgirt there were thirteen, twelve, and thirteen Armenian churches, respectively. [25] The 1878 Patriarchate census of the Moush prefecture, for unknown reason, mentioned only four churches in Manazkert. The 1902 Patriarchate census of the population of towns and villages on the Plain of Moush and its vicinity listed about 63 churches, many dilapidated. The 1913 Patriarchate census listed nineteen churches in the county, a figure that Kévorkian and Paboudjian raised to 25, using supplementary Patriarchate census data available to them.

Abdodrek (Abdo)

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Adakend

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Aghveran

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Akner Nerkin

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin).

Akner Verin

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg).

Aladjakhan

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Alyar

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Aynakhodja

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Hovhannes was built of wood.

Bagran

One unnamed church.

Bane

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Banzde

One unnamed church.

Damian

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Derik

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Astvatsatsin was built of wood, in 1800. Mirakhorian reported that Surb Astvatsatsin was an unsightly and dark, yet wonder-working church. A local folktale had it that moufflons once came and lay down at the entrance with their necks uncharacteristically craned. After waiting for an hour or so, the pastor asked the bell-ringer to bring salt so have it blessed before slaughtering one of the animals. Considered a sacrificial offering to God, called matagh in Armenian, boiled meats were then handed out to the meek and needy. [26] Two dilapidated churches of Saint James (Surb Hakob) and Saint Sahak (Surb Sahak) also stood in the village. Two serving clergymen, Father Sahak and Father Baghdasar.

Djabalverdi

One unnamed church.

Dolaghbash

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). Surb Gevorg was built of stone. There was another, unnamed and dilapidated, church in the village. Two serving clergymen, Father Baghdasar and Father Gevorg.

Dorakhan

One unnamed church.

Dugnuk

One unnamed church. Two serving clergymen, Father Shmavon and Father Haroutiun.

Gharaghaya

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). Surb Astvatsatsin was an ancient church. One serving clergyman, Father Haroutiun.

Gharghalegh Nerkin

One unnamed church.

Gharghalegh Verin

One unnamed church.

Ghazgyol

One unnamed church. Ghazgyol is purportedly identified with Khazghoughk, a village which figured in a medieval Armenian chronicle as a locality housing two churches, Saint Sion (Surb Sion) and Saint George (Surb Gevorg). In the late twelfth century, a vicar by the name of Avetis bought out an ancient gospel from certain Stepanos, apparently a village priest, and donated it to these churches. [27]

Ghlechi

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Hadjibot

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Hadji Yusouf

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Hasan Pasha

One unnamed church. In the large graveyard near the village stood tombstones bearing Greek and Armenian inscriptions.

Kanikor

One unnamed church. The church was an ancient structure located near the eastern quarter of the village.

Karahasan

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Keoshk

One unnamed church. One serving clergyman, Father Mkrtich.

Kesan

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Khanigegh

The Church of Saint James (Surb Hakob). According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Hakob was built of wood, in 1841. There was another, unnamed and dilapidated, church in the village.

Kharaba Ghasmik

One unnamed church.

Kharabasor

One unnamed church.

Kharaghadj

One unnamed church.

Khasmik

The Church of Saint Toukhmanuk (Surb Toukhmanuk). One serving clergyman, Father Khachatour.

Khotanlu

The Church of John the Baptist (Surb Karapet). Formerly a monastery, Surb Karapet was an ancient, yet simple and unornamented, structure. According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Karapet was built of wood. Several stones of the altar were engraved with cuneiforms. One serving clergyman.

Koushtian

One unnamed church.

Koutkan

One unnamed dilapidated church. The ruins were located near the eastern quarter of the village.

Kzelyusouf

One unnamed dilapidated church.

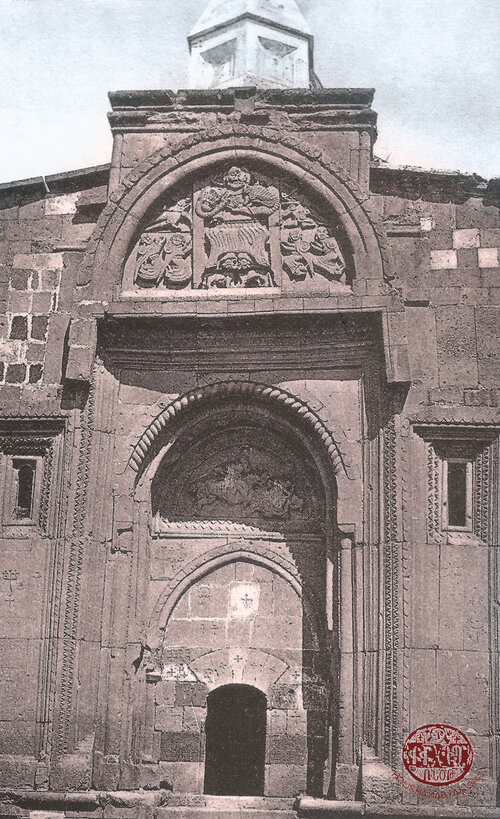

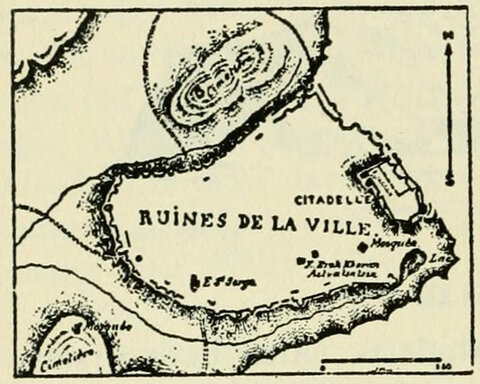

Manazkert

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) and the Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis). According to Lynch, Surb Astvatsatsin was a pleasing peace of architecture and evidently a royal chapel. Another name Surb Astvatsatsin was known under, Yerek Khoran Astvatsatsin, was derived from the three apses that the church was complete with. The interior had a length of 62 feet and a breadth of 40 feet. The nave was separated from the aisles by two rows of three pillars apiece. The walls had once been covered with frescos. [28] According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Astvatsatsin was destroyed in 1885; the roof fell in and one of its apses crumbled. Surb Sargis, according to Bishop Srvandztiants, was an ancient and splendid edifice. [29] This view is shared by Lynch, who reported that Surb Sargis apparently was a town church, complete with three apses. The interior had a length of 66 feet and a breadth of 39 feet. Built in 1139, Surb Sargis, according to Ter-Karapetian, in the early twentieth century was still a place of worship. However, the church, in Lynch’s words, was “maintained in a filthy state.” The two rows of three pillars were seen still standing in the late nineteenth century. A little sacristy adjoined a chapel on the north. Abutting on the western front of this sacristy was placed an independent chapel, already a ruin by then. The chapel was known under the name “church of the Arabs,” or Arab kilise, in Turkish. [30] Lynch presumed that by the ethnonym “Arab,” Turks denoted the Nestorians, possibly because in the early Middle Ages the Nestorian Christianity was spread in the Arabian Peninsula. Tevkants reported the Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) and the Church of Saint Minias (Surb Minas) in the town.

Reconstruction of the tenth-century plan of Manazkert. The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) is in the lower right quadrant. The Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis) is in the lower central quadrant. (Source: Jacque de Morgan, The History of the Armenian People: From the Remotest Times to the Present Day, Boston, 1965).

Near Surb Sargis stood a small, yet beautiful, unnamed church. Two other churches in Manazkert were the Church of Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) and the Church of Saint James (Surb Hakob). As a consequence of a devastating earthquake in May of 1903 centered near Mount Sipan, [31] all churches, except for Surb Sargis, were reduced to rubble. [32] Two clergymen, who apparently served at one of the churches mentioned above, were Father Poghos and Father Yeghiazar.

Marmous

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Hovhannes was built of wood. The village name derives from a biblical theme and is a designation of the nominal compound “mar+Moses” (translated from Persian as “Lord Moses”) or, in Armenian, “Ter Mus (Movses).”

Mirzé

An unnamed dilapidated church.

Molladarman

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Molla Hasan

One unnamed church. According to Ter-Karapetian, the church was an ancient structure.

Molla Mustafa

One unnamed church.

Nadarsheykh

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Noradin

The Church of Saint James (Surb Hakob). Built of stone, Surb Hakob was complete with three apses. Two serving clergymen, according to Mirakhorian. Ter-Karapetian reported that there was one serving clergyman, Father Hovhannes. The 1878 Patriarchate census listed the Church of Saint Stephen (Surb Stepanos) in the village.

Oghdjin

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). Surb Gevorg was a splendid four-pillar structure built of stone, in 1639. In the churchyard stood a beautiful chapel. Legend had it that the village name originated from the Armenian word voghdjuin, meaning “greeting,” as if a merchant passing through the village saw trees exchanging greetings with one another. In order to be certain of what he saw, the merchant commissioned the local priest to say mass. The trees responded to the liturgy with greeting each other by bowing. [33] Tevkants reported the Church of Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) in the village.

Ozor (Oghudjan)

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Roustamgetik

The Church of Saint Toukhmanuk (Surb Toukhmanuk). Two serving clergymen. The 1878 Patriarchate census listed the Church of Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) in the village.

Sardaud

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). Ter-Karapetian reported that there was an unnamed dilapidated church built of stone and complete with elaborate designs.

Shamé

One unnamed church.

Shebo

One unnamed dilapidated church. In the late seventeenth century, an Armenian copy of an ancient gospel was made in the village.

Sulduz

The Church of Holy Saviour (Surb Amenaprkich). According to Ter-Karapetian, Surb Amenaprkich was an ancient church built of stone. Not far from the village, near a monumental bridge over the Aratsani (Murat) River, stood the Holy Seal (Surb Nshan) church. In the mid-nineteenth century, Surb Nshan was already in a dilapidated state; only crumbling walls and the foundation stone remained. A few khachkars were scattered here and there. Three of the thirteen arches of the beautiful bridge were demolished as a result of intertribal clashes between the local Kurdish tribes of Hayderan and Hasanan. [34]

Sultanlu

The Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis). Formerly a monastery, the church stood near the northern quarter of the village.

Tatarghazi

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Tondrak

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). Surb Astvatsatsin was a splendid four-pillar structure built of stone, in 1168. One serving clergyman. Tevkants reported that the village housed the Church of Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) which, in his words, was a splendid church. Two other churches, the Church of Saint James (Surb Hakob) and the Church of Saint Stepanos Priest Housik’s Son (Surb Stepanos Ter Houskan vordu yekegheci), became dilapidated by the late nineteenth century. Stepanos was one of the most revered saints in Manazkert and the neighboring counties. Outside of Manazkert, near Berkri (present-day Muradiye), a town located ten kilometers (six miles) northeast of the easternmost coastline of Lake Van, there was also a monastery where Stepanos was venerated, also known as the monastery of the Holy Mother of God at Argelan (Argelana Surb Astvatsatsin vank). [35]

Yaramish

One unnamed church.

Yekmal

One unnamed church.

Ziraklu

The Church of Saint Stephen (Surb Stepanos).

Places of pilgrimage in the Malazgirt county

Along with monasteries and churches, there were chapels, mountains, khachkars, and spring-wells that Manazkert Armenians regarded with reverence as they went there on pilgrimages or for veneration. The longest pilgrimage occurred after Easter, when for forty days the villagers would go to the many places in the county and beyond that they considered sacred. The pilgrimage was followed by occasional daily or weekly fasts. The terrain of the Malazgirt county was strewn with undamaged or fragmented khachkars, as well as half-ruined or ruined (in Armenian, shabatatsial) convents, some of which were considered sacred. Even heaps of stones, many reduced to mere bumps (in Armenian, derbookner) over the centuries, were considered sacred and thus were not forgotten. The “derbookner” bumps were venerated especially by the local Armenian women, who burnt incense and murmured prayers at their sites. [36] One such derbook, dating from the fourteenth century and bearing the name of a stonemason etched in a horizontal slab at the top, lay north of the town of Manazkert. [37]

Akn spring-well at unknown location

Legend had it that every year, in the early morning of the day of the feast of Hambardzum (Ascension), angels placed a life-giving apple (in Armenian, anmahakan khndzor) in the water of the well “Akn” that sprang at an unknown location in Malazgirt county. It was believed that whoever arrived at the sacred spring-well before the others, would see the wonder apple. But if one tried to reach for it, the apple would immediately disappear. [38]

Aynakhodja

The ruins of an unnamed monastery that stood near the northern quarter of the village were considered a sanctuary by the locals.

Bostankhaya

Across the village rose a cliffy barrow with ledges in the form of a staircase leading to the top, where a garden with planting beds was placed. The barrow earned the village the name Karapartez (translated from Armenian as “rock garden”), or Bostankaya in Turkish. [39] At the top of the barrow also stood ruins of an ancient fortress near which, half-buried in the ground, were hewn stones, some bearing cuneiform writing of the Urartian king Menua. A large tombstone near the ruins was considered a sanctuary, because, according to legend, in it laid a giant (in Armenian, aznavour). [40]

Lousaghbyur spring-well at Oghdjin

Near the Saint George (Surb Gevorg) church sprang the well “Lousaghbyur.” The sick used its water to bathe sore eyes, while the healthy sprayed it on body parts to prevent sickness. In fact, there were quite a few spring-wells that were called “Lousaghbyur” near intact or dilapidated monasteries. Legend had it that after bathing his eyes with the well-water, a blind man had recovered his sight, thus the name “lousaghbyur,” that is, waters endowed with the power to bring the light of day.

Mount Sipan

Western slopes of this mountain, which rose immediately north of Lake Van, formed part of the southernmost edge of the kaza of Malazgirt. A snow-capped dormant volcano, Mount Sipan was the second highest peak in the Armenian Highlands after Mount Ararat (Masis). Its massive dome in the shape of a truncated cone was considered a sanctuary, because, according to legend, in it laid aznavourner, the giants. Malazgirt villagers would go on a pilgrimage to the slopes of the mountain in order to make sacrificial offerings. [41]

Saint Daniel (Surb Daniel) monastery at Kop

Once a year, for the feast of the Transfiguration of Jesus (Vardevar or Vardavar), Armenian residents of adjacent villages of Bulanik and Manazkert counties made a pilgrimage to the Surb Daniel monastery. During the festivities, horsemen grass hockey djirid, as well as dances, chants, and sacrificial offerings, were arranged at the monastery. Located in the kaza of Bulanik 24 kilometers (fifteen miles) southeast of Manazkert, Surb Daniel is not to be confused with the homonymous monastery in the kaza of Malazgirt mentioned above or its chapel mentioned below.

Saint Daniel (Surb Daniel) chapel at Manazkert

Situated at a short distance east of Manazkert, the chapel apparently formed part of the homonymous monastery. Surb Daniel chapel was considered a sanctuary not only by the Armenians, but also the Kurds, who made their own pilgrimages there.

Saint Hovhannes Odznetsi (Surb Hovhannes Odznetsu matour) chapel at Noradin

This small, cabin-like chapel, called “loostun” in the local parlance, stood at the homonymous monastery. Surb Hovhannes Odznetsu chapel was considered a sanctuary and was visited for veneration especially by the local Armenian women.

Saint Nicholas monastery of Apahunik (Apahuniats Surb Nikoghayos) at Kurudja

According to a fourteenth-century Armenian chronicle, the monastery was considered a place of pilgrimage. [42]

Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis) monastery at Dugnuk

The monastery was considered a sanctuary where the locals went to worship Surb Sargis. A general in the Roman army, Sargis suffered martyrdom together with his son Martiros after refusing to recant his Christian faith. In Malazgirt, sanctuaries where Surb Sargis was venerated were fewer compared to places of worship of other saints, such as Saint George (Surb Gevorg) or Saint Toukhmanuk (Surb Toukhmanuk). Nevertheless, Surb Sargis was one of the most revered saints in the county [43] and the neighboring kaza of Bulanik. The saint was held in veneration insomuch that local Armenians would observe a fast for him.

Spring-well at the Holy Seal (Surb Nshan) church at Sulduz

Near the Surb Nshan church sprang a spring-well. Its water tasted sweet and was considered life-giving (in Armenian, anmahakan djour) and thus sacred. Stemming from a cliff, the water flowed through a cupped rock and into the Aratsani (Murat) River, which was two stones’ throw away.

Red monastery (Karmir vank) and boulder (Manazkerti seghankar) at Manazkert

Within an hour’s walk southwest of Manazkert there were ruins of two or three churches, which served as a place of pilgrimige for the Armenian villagers. A popular folk tradition held that at the site of the ruins once stood a monastery, called “Red Monastery” (in Armenian, Karmir vank). [44] Not far from Karmir vank stood a large boulder measuring two by one meter and a half (around seven by five feet). It was a naturally hewn rock, flat and oval-shaped at the top, and carved out like trough. Armenians called it “seghankar” or “seghani kar,” while amongst Kurds the boulder was known as “giavre kafran,” meaning “idolaters’ boulder.” Legend had it that in ancient times at the site of the boulder stood a heathen temple. [45] Several sources identified Karmir vank as a sanctuary located southwest of Manazkert. Hakobyan et al., however, placed the boulder, which reportedly stood not far from Karmir vank, south of Manazkert, near the deserted Armenian village of Sndjan.

1) The title page of Ghukas Inchichian’s treatise Ashkharagroutiun choric masanc ashkhari (The Geography of the Four Cardinal Points), volume 1. Venice, 1806.

2) The title page of A-To's (Hovhanness Der Mardirossian) The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis and Erzurum [in Armenian], Yerevan, 1912.

3) The title page of Hamazasp Voskian's Vaspourakan-Vani vankere (The Vaspourakan-Van Monasteries), volume 1, Vienna, 1940.

Tempietto chapels (Taghavarikner) at Manazkert

Scattered throughout the town were six tempiettos “taghavarikner,” some bearing cuneiform writings. Two of them were called simply “sacred,” or “surb” in Armenian, while the other four “Saint Toukhmanuk” (Surb Toukhmanuk). One of the most revered saints in Manazkert and several other counties, Toukhmanuk, meaning “swarthy lad” in Armenian, was a Kurdish boy sanctified by the Armenians after he converted to Christianity and suffered martyrdom at the hands of his Muslim co-religionists. [46] The tempiettos were considered places of pilgrimage, especially by the women, who on Saturday nights visited them, burnt incense, lit candles and oil-lamps, and murmured: “Astvats, voghormi mer nakhnyats hogouin” (Lord, have mercy on the souls of our forebears). [47]

The Miracle worker (Skanchelagorts) at the Holy Seal (Surb Nshan) monastery

Surb Nshan stood on a southern slope of Mount Sipan near Artske and contained a holy relic, called Skanchelagorts in Armenian. The relic was believed to be a piece of the bronze basin in which Jesus had been washed just after his birth. Mary and Joseph were said to have brought the bronze splinter to Judea, from where Apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew brought it to Armenia. Surb Nshan was located just outside of the southernmost edge of the kaza of Manazkert, but the villagers would go on a pilgrimage to the monastery, because the relic was believed to have the power to cure diseases, such as bubonic plague, smallpox, etc. [48]

The Mother church (Mayr yekegheci) at Manazkert

In the eastern quarter of the town stood a religious edifice, which the locals called “Mother church” (in Armenian, Mayr yekegheci). The walls and the corners of the structure, as well as the elaborate khachkars that stood nearby, were considered sacred. Near the Mother church were the ruins of a smaller, arched church. The church was almost entirely embedded in the ground to the extent that its flattened roof formed a section of a country road.

Unnamed sanctuary (monastery) at Sultanmud

Near the village there was a sanctuary, purportedly a monastery, which was still seen in the late nineteenth century. After Armenians had to abandon the village, apparently during the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish war, the sanctuary was destroyed by a local Kurdish sheikh.

- [1] Hakobyan, Tadevos. “Manazkert,” in Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Press, 1981), volume 7, p. 210. (in Armenian)

- [2] Inchichian, Ghukas. Storagroutiun hin Hayastaniayts (Description of Ancient Armenia). (Venice: Island of Saint Lazarus, 1822), p. 115. (in Armenian)

- [3] Kristonya Hayastan Hanragitaran (Christian Armenia Encyclopedia). (Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishers, 2002), p. 35.

- [4] Papian, Mher. “Manazkerti yekeghacakan zhoghov 726” (The 726 Manazkert Ecumenical Council), in Kristonya Hayastan Hanragitaran (Christian Armenia Encyclopedia). (Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishers, 2002), pp. 668-669. (in Armenian)

- [5] Bedrosian, Robert. “Armenia during the Seljuk and Mongol Periods,” in Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, Richard Hovannisian (ed.), volume 1. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), pp. 246-247, 249.

- [6] Nicolle, David. Manzikert 1071: The Breaking of Byzantium. (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2013), p. 91.

- [7] Inclosure in No. 25. Consul Taylor to the Earl of Clarendon. Erzeroom, March 19, 1869, in British Documents on Ottoman Armenians, volume 1: Turkey No 16 (1877), pp. 16-36, No. 13/1.

- [8] Lynch, H.F.B. Armenia: Travels and Studies, volume 2: The Turkish Provinces. (London, New York: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1901), p. 275.

- [9] Vantir or Saint Aghperig Monastery (Vantir or Surp Aghperga Vank), in Collectif 2015: Réparation, Union Internationale des Organisations Terre et Culture.

- [10] Ormanian, Malachia. Hayots Yekeghecin yev ir patmoutiune, vardapetoutiune, varchoutiune, barekargoutiune, araroghoutiune, grakanoutiune ou nerka kacoutiune (The Church of Armenia: Her History, Doctrine, Rule, Discipline, Liturgy, Literature, and Existing Condition). (Constantinople: V. & H. Ter-Nersessian Publishing House, 1911), p. 262. (in Armenian)

- [11] Bdeyan, Sargis, and Misak Bdeyan. Harazat Patmutioun Tarono (The Authentic Story of Taron). (Cairo: Sahak-Mesrop Publishing House, 1962), p. 335. (in Armenian)

- [12] Petrossian, Hakob. “Verdjin aradjnorde Taron ashkhari (Vardan tsairagouin vardapet Hakobyan) (The Last Clerical Leader of the Land of Taron: Supreme Archimandrite Vardan Hakobyan),” in Etchmiadzin Religious-Armenological Review (no. 68 (12)) (Etchmiadzin: Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church Press, 2012), p. 60․ (in Armenian)

- [13] Teodik. Koghkota Trqahye Hogevorakanoutyan yev ir Hotin Aghetali 1915 Tariin (The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915). (Tehran: S.N., 2014), pp. 71, 141-142. (in Armenian)

- [14] Kévorkian, Raymond, and Paul Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du genocide. (Paris: ARHIS, 1992), p. 59.

- [15] Lynch, op. cit., p. 171.

- [16] Parsegian, V. Lawrence (Project Director, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute). Malazgirt (Manaskert) area, Turkey (A-2001), 5: 033; 6: 080-082, in Cumulative Index and Guide to the Armenian Architecture: Microform Collection, Books I-VII. Leiden: Inter Documentary Company, 1990.

- [17] Matevosyan, Karen. “Vimagrakan nshkharner Arevmtian Hayastanic” (Lithographic Inscriptions from Western Armenia), in Etchmiadzin Religious-Armenological Review (no. 72 (4)) (Etchmiadzin: Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church Press, 2015), pp. 148-149. (in Armenian)

- [18] Tevkants, Aristakes. Aicelutioun i Hayastan (A Journey to Armenia), 1878. Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Press, 1985. (in Armenian)

- [19] Safrastyan, Aram. Kostandnupolsi hayots Patriarqarani koghmic Turqiayi ardaradatoutian ev davananqneri ministroutian nerkayacvats haykakan yekeghecineri ev vanqeri coucaknern ou taqrirnere (1912-1913) (Lists of and Reports on Armenian Churches and Monasteries in the Ottoman Empire Presented to the Ottoman Ministry of Justice and Religious Minorities by the Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople (1912-1913). (Etchmiadzin: Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church Press, 1965, 23 (2) and 22 (2-4)), pp. 41, 182-183. (in Armenian)

- [20] Hakobyan, Tadevos, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan. Hayastani ev harakits shrjanneri teghanounneri bararan (Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories). (Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 1986), volume 1, pp. 975, 485 and volume 2, p. 469. (in Armenian)

- [21] The 1902 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census of the population of towns and villages on the Plain of Moush and its vicinity (collected by Gegham Ter-Karapetian), pp. 157-166. (in Armenian)

- [22] Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan. Hayots pashtamunqayin vayrer (Places of Worship in Armenia). (Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 2009), p. 121. (in Armenian)

- [23] Massis, July 12 (no. 28). Constantinople, 1903.

- [24] Ibid.

- [25] Okcu, Naci, and Hasan Akdağ, Salname-i vilayet-i Erzurum (1287/1870-1288/1871-1289/1872-1290/1873): Erzurum il yıllığı. (Annual Salnamé of the Erzrum Province, 1870, 1871, 1872, 1873). Erzurum: Atatürk Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi, 2010, pp. 205, 317, 442. (in Turkish)

- [26] Mirakhorian, Manuel. Nkaragrakan oughevorutioun i hayabnak gavars Arevelian Tachkastani (A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions of Eastern Turkey). (Constantinople: Partizpanian Publishing House, 1885), volume 3, pp. 60-61. (in Armenian)

- [27] Hakobyan et al., op. cit., volume 2, p. 617.

- [28] Lynch, op. cit., p. 271.

- [29] Srvandztiants, Garegin. Toros Aghpar. Hayastani Champord (Toros Aghpar: A Traveler around Armenia). (Constantinople: G. Baghdadlian (Aramian) Publishing House, 1885), volume 2, p. 278.

- [30] Lynch, op. cit., p. 272.

- [31] Review of the Permanent Seismic Committee of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences, volume 2. (Saint Petersrburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences Press, 1905), p. 94.

- [32] Teodik, op. cit., p. 141.

- [33] Ghanalanyan, Aram. Avandapatoum (Armenian Traditions). (Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Press, 1969), p. 189. (in Armenian)

- [34] Mirakhorian, op. cit., pp. 58-59.

- [35] Voskian, Hamazasp. Vaspourakan-Vani vankere (The Vaspourakan-Van Monasteries), volume 1. (Vienna: Mkhitarian Press, 1940), pp. 357-378. (in Armenian)

- [36] Massis, July 12 (no. 28). Constantinople, 1903.

- [37] Srvandztiants, op. cit., volume 2, p. 278.

- [38] Ghanalanyan, op. cit., p. 105.

- [39] Hambavaber, June 19 (no. 25). Tiflis, 1916.

- [40] Hakobyan et al., op. cit., volume 1, p. 731.

- [41] Bensé. “Hark (Msho Bulanekh)” (Hark։ Bulanik County of Moush), in Armenian Ethnography and Folklore, volume 3. (Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Press, 1972), p. 50. (in Armenian)

- [42] Ararat, April 30 (no. 4). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, 1872.

- [43] Haykuni, Sargis. Bagrevand. djrabashkh gavar (Bagrevand: A Water Distributing County), Etchmiadzin, 1894, cited in “Toukh Manuk (Proceedings of the symposium).” (Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing House, 2001), p. 9. (in Armenian)

- [44] Byuzandion, June 22-July 5 (no. 1127). Constantinople, 1900.

- [45] Mirakhorian, op. cit., pp. 54-55.

- [46] Bensé. “Bulanekh kam Hark gavar” (Bulanik or Hark County), in Ethnographical Journal, volume 6. (Tiflis, 1900), pp. 25-26. (in Armenian)

- [47] Mirakhorian, op. cit., p. 48.

- [48] Ibid., p. 42.