Kaza of Siirt/Sghert – Demography

Author: Robert A. Tatoyan, 01/12/2021 (Last modified: 01/12/2021) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

In antiquity, Sghert was the center of the Kherhet or Serkhetk district of Aghtsnik province of Greater Hayk (Greater Armenia). According to a widely accepted theory, Sghert was named after this ancient district. [1]

The city of Siirt/Sghert came under Ottoman rule in the early 16th century. The Ottoman authorities designated it as the administrative center of the eponymous kaza (sub-district) and sandjak (district) within the vilayet (province) of Diyarbakir. [2] In the 17th century, Siirt was also listed as a sandjak of the Van eyalet. [3]

In the mid-19th century, as part of the Tanzimat reforms, the Ottoman authorities initiated a restructuring of the empire’s administrative divisions, which also affected the territory of Western Armenia. In 1878-1879, the sandjaks of Bitlis and Moush were separated from the vilayet of Van, and were merged into a previously nonexistent vilayet, the vilayet of Bitlis. In 1880, the sandjak of Siirt was removed from the jurisdiction of the vilayet of Diyarbakir and attached to the vilayet of Bitlis. [4]

After the creation of the vilayet of Bitlis, in the 1880s and 1890s, the authorities redrew the internal and external borders of the vilayet’s administrative units, including the sub-district of Siirt. As a result of these changes, Hazzo and Khaplchozu were removed from the territory of the Siirt sub-district and attached the district of Moush as the Sassoun sub-district. [5]

1) Vital Cuinet, La Turquie d’Asie [Asian Turkey], volume 2, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1891.

2) Vladimir T. Mayewski, Voenno-statisticheskoe opisanie Vanskogo i Bitlisskogo vilayetov [The Military Statistics of the Van and Bitlis Provinces], Tiflis, Caucasus Military District Headquarters Press, 1904.

3) Teotig, Գողգոթա հայ հոգեւորականութեան եւ իր հօտին աղէտալի 1915 տարին [The Calvary of the Armenian Clergy and its Followers in 1915], 1st Volume, Constantinople, 1921.

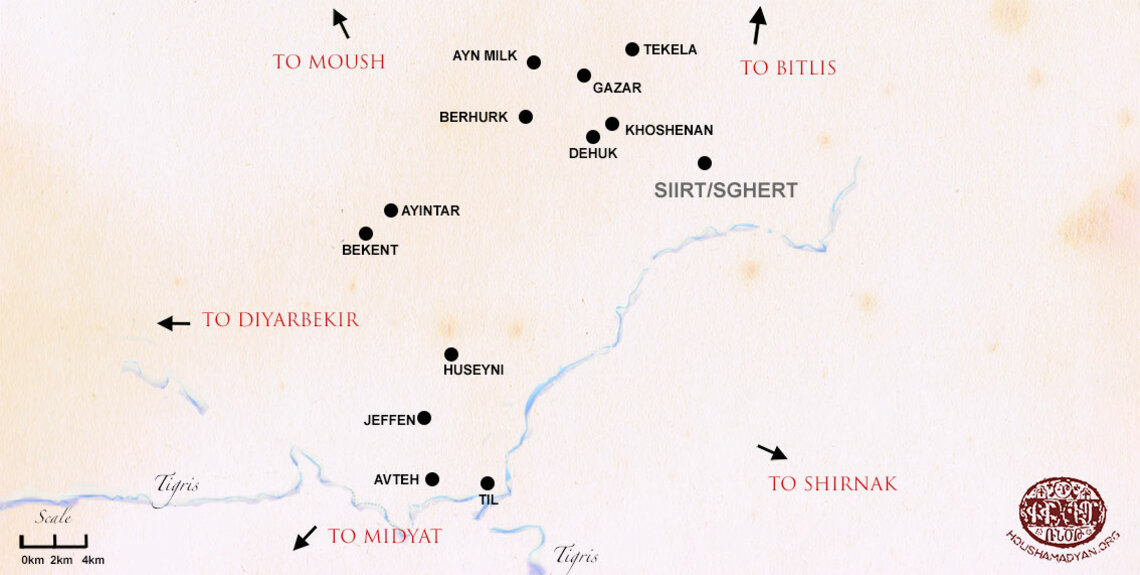

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the district of Siirt covered an area of 7,090 square kilometers in the south of the vilayet of Bitlis. Its borders were: in the south-east, the Modgan, Bitlis, and Khizan sub-districts of the vilayet of Bitlis; in the south-west, the Sassoun sub-district of the district of Moush; in the east, the province of Van; and in the south and west, the province of Diyarbakir. The Siirt district was divided into five sub-districts, which were Siirt, the central sub-district (merkez kaza in Turkish), covering an area of 797 square kilometers; Erouhi, covering an area of 1,992 square kilometers; Parvar, covering an area of 1, 536 square kilometers; Kharzan, covering an area of 1,570 square kilometers; and Shirvan, covering an area of 1,195 square kilometers. [6]

The sub-district of Siirt occupied a central geographic position in relation to the district’s other sub-districts. It shared borders with three other sub-districts: in the west, it bordered Kharzan; in the north-east, it bordered Shirvan; and in the east and south, it bordered Erouhi.

In the late 19th-early 20th centuries, the entire territory of the district of Siirt was under the jurisdiction of the Sghert Bishopric/Prelacy, itself under the jurisdiction of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople. [7]

In terms to demography, Siirt/Sghert is one of the least studied areas of Ottoman Armenia. Historians who have researched the subject have noted the dearth of regular census/survey information regarding the sub-district’s Armenian and non-Armenian population. Vladimir Mayevsky, the deputy consul of the Russian Empire in Van in 1895, noted in his work A Military-Statistical Description of the Provinces of Van and Bitlis that he could find only a few sources of information about this sub-district. He also stated that to compile the statistics that he presented in his work, he had relied on his own personal observations, as well as the figures provided by French researcher Vital Cuinet and by Ottoman Salnames. [8] These sources often provided contradictory information. [9]

Garo Sassouni was another prominent scholar who noted the dearth of statistical data regarding the population of the sub-district of Siirt. [10]

In 1913, when the Sghert Prelacy sent its survey of the Armenian population of the sub-district to the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate, Father Kevork Nalbandian, who served as the interim prelate of the prelacy, sent a letter to the Patriarchate alongside the survey. In this letter, he explained that the work of collecting demographic information on the local Armenian population had been complicated by the fact that the area’s Armenian-populated settlements were scattered across a wide area and were separated by great distances. [11]

In the late 19th-early 20th centuries, across the sub-district of Siirt, Armenians lived in the city of Siirt/Sghert and in approximately 10 villages/settlements. There were no communities that were exclusively Armenian-populated. Armenians across the sub-district mostly lived alongside the local Kurds (in both Ottoman sources and later Armenian surveys, the Kurds were listed according to their religious affiliation, namely as “Muslims”).

In some mostly Kurdish-populated settlements, Armenians were not a permanent presence. Two or three Armenian families would live in these villages as marabas (tenant famers) or artisans. They would often leave these villages when subjected to persecution or when facing lack of employment.

The largest Armenian-populated villages in the sub-district had Armenian populations of 13 to 15 households. Outside of the city of Sghert, none of the Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district had Armenian schools or Armenian churches.

The Hamidian massacres were a great blow to the Armenian population of Sghert. In the city of Sghert, the carnage occurred on November 3 (16), 1895. The bloodthirsty mob broke into and robbed the Armenian church, prelacy, and school. The interim prelate, Father Teotoros Divrigian, was seriously injured. An Armenian priest and the interim prelate’s servant were killed. According to contemporary news reports, the number of Armenians killed in the city was approximately 70. [12] Many women and girls were abducted. Many of the city’s Armenians converted to Islam under the threat of death. [13]

In October-November 1895, additional massacres occurred in 12 Armenian-populated villages in the Erouhi sub-district and 20 Armenian-populated villages in the Shirvan sub-district of the district of Sghert. [14] Massacres also occurred in other parts of the district.

Although in later years, most of the Armenians who had been forcefully converted to Islam returned to their faith, many previously Armenian-populated villages and settlements remained deserted.

Three separate sources provide detailed information regarding the Armenian population of Sghert, broken down by settlement or locality. These sources are:

- The survey prepared by Father Arisdages Devgants in 1878 and commissioned by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate. [15] According to this survey, Armenians lived in five localities in the sub-district, including the city of Sghert, and their total population was 2,489. [16]

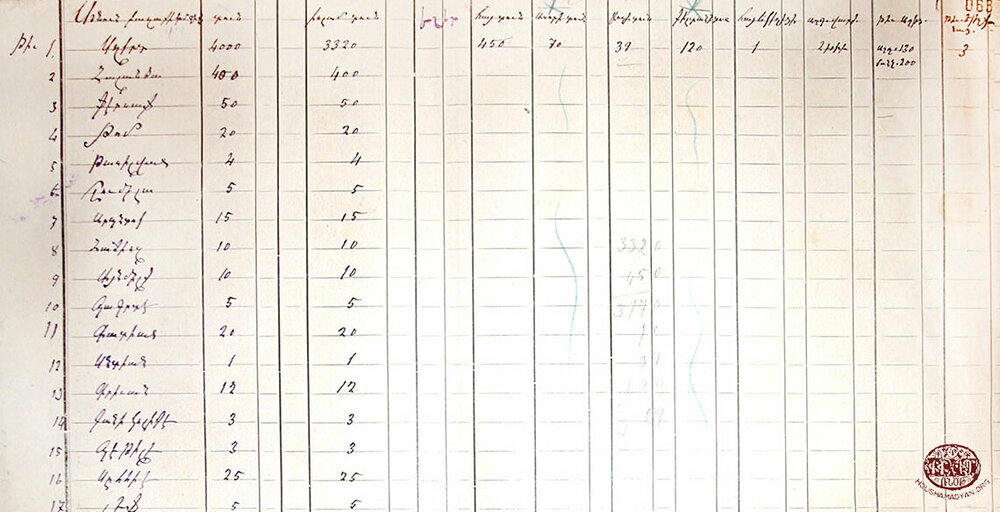

- The 1902 report prepared by the Sghert Prelacy and titled Survey of Shgert and its Dioceses. [17] According to this report, the entire sub-district, including the city of Sghert, had 12 Armenian-populated settlements, with a total Armenian population of 590 households. [18]

- The survey prepared by the Sghert Prelacy in late 1913 and commissioned by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate. [19] Of the 70 settlements of the sub-district included in this survey, only 10 had an Armenian population (including the city of Sghert). The total Armenian population of the sub-district was 545 Armenian households, including 52 Protestant households. [20] This survey also noted that the sub-district was home to 5,097 Muslim households, 153 Syriac households, and 236 Chaldean households (identified as kildanis). [21] According to the calculations of French-Armenian researchers R. Kévorkian and P. Paboudjian, which were based on this data, the sub-district had an Armenian population of 4,437. [22]

Demographic information regarding the Armenian population of Sghert is also provided by the following sources, but without a detailed breakdown of population by locality:

- According to French surveyor Vital Cuinet, in 1891, the Armenian population of the sub-district was 6,020, consisting of 1,204 households. Of these, 1,080 households, or a total of 5,400 Armenians, were Apostolic; and 124 households, or 620 Armenians, were Protestant. [23] According to Cuinet, approximately half of this Armenian population, or 2,700 individuals, lived in 37 villages in the sub-district (outside of the city).

- According to V. Mayevsky, in 1899, the Armenian population of the sub-district was 6,622. Mayevsky calculated this number by taking Cuinet’s figure and simply increasing it by 10 percent. [24]

- According to the Ottoman census, in 1914, the Armenian population of the sub-district was 2,630, of whom 2,218 were Apostolic and 412 were Protestant. [25]

Below, we present detailed information regarding the Armenian population of the towns and villages of the sub-district of Siirt, based on the surveys conducted by Devgants in 1878 and the Sghert Prelacy in 1902 and 1913, in addition to some other sources. We will first examine the Armenian population of city of Sghert, and then proceed to the sub-district’s other settlements in [Armenian] alphabetical order.

These settlements’ present-day Turkish names were obtained from the website Index Anatolicus (www.nisanyanmap.com) and other sources.

City of Sghert, Sgherd, Serhedk, Serkhet, Kherhet, Kherherk, Perkherk [Siirt]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 55' 37'' N, 41° 56' 43'' E

The city of Sghert was one of the largest Armenian settlements not only in the sub-district, but also the entire district.

According to the 1878 Devgants survey, the total population of the city was 6,412, consisting of 2,400 Armenians and 4,012 Kurds. [26]

According to Cuinet’s figures from 1891, the city of Sghert consisted of 3,000 households and had a total population of 15,000, of which 1,936 households, or 9,680 individuals, were Muslims; 560 households, or 2,800 individuals, were Apostolic Armenians; 104 households, or 530 individuals, were Protestant Armenians; 300 households, or 1,500 individuals, were Catholic Syriacs (Chaldeans); and 100 households, or 500 individuals, were Jacobite Syriacs or belonged to other ethno-religious groups. [27] Therefore, according to Cuinet’s figures, Armenians (both Apostolic and Protestant) constituted 22 percent of the city’s population; and Armenians and other Christians constituted 34 percent of the city’s population.

In its 1902 report, the Sghert Prelacy stated that “according to the authorities’ records” (meaning, according to the surveys of the Ottoman authorities), there were 300 Apostolic Armenian households in Sghert, but that the actual number was 500 households and 5,000 individuals. According to this report, the city was also home to 25 Armenian Protestant and two Armenian Catholic households, alongside 4,000 Muslim households, 80 Chaldean households, and 30 Syriac households. [28]

According to the figures of the 1913 Sghert Prelacy, the city was home to 450 Apostolic Armenian households and 39 Armenian Protestant households, for a total of 489 Armenian households. According to the same survey, the non-Armenian population of the city consisted of 3,320 Muslim, 70 Syriacs, and 120 Chaldean households. [29] Using these figures, French-Armenian researchers R. Kévorkian and P. Paboudjian concluded that the total Armenian population of the city of Sghert was 4,032. [30]

The information provided by other Armenian sources regarding the Armenian population of the city of Sghert on the eve of the Armenian Genocide is mostly based on the figures of the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey. For example, Teotig rounded up the prelacy’s figures, and estimated the Armenian population of Sghert to be 500 households, of which 50 were Protestant. [31]

According to Western Armenian researcher S. Dzotsigian, who used the testimonies of Genocide survivors as a primary source, the city of Sghert had an Armenian population of about 6,000 in 1915, out of a total population of 15,000. [32]

Aynmilk, Aynmyulk, Ayn Milk [Pınarova]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 59' 11''N, 41° 48' 51''E

According to the 1878 Devgants survey, Aynmilk was home to 24 Armenians. [33]

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village had a population of four-five Armenian households and 10 Muslim households. [34]

The 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population. The survey noted that the village was exclusively Muslim-populated, with a population of 10 Muslim households. [35]

Ayndar, Ayntar [Ağaçlıpınar; Aghachlipinar]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 53' 42'' N, 41° 42' 14'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, this village had an Armenian population of 10 households. The survey noted that many Armenians had fled to Ayndar from the village of Bekend in 1901 (“fled from Bekend last year”), but no information is provided on what prompted these Armenians to flee their homes. According to the survey, in addition to these Armenians, the village was home to eight Muslim households. [36]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, Ayndar was home to three Armenian households, two Muslim households, and one Syriac household. [37] The significant decline in the Armenian population between 1902 and 1913 was most probably due to the return of the abovementioned refugees back to Bekend.

Avte, Avti, Inner Oyte [Balıklı]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 44' 2'' N, 41° 44' 10'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to six Armenian households and 15 Muslim households. [38]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, Inner Oyte was exclusively Muslim-populated, with a total population of 10 Muslim households. [39]

Kazar, Kezer [Pınarca]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 58' 41'' N, 41° 51' 8'' E

According to the 1878 Devgants survey, Kazar was home to 16 Armenians. [40]

The 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, Kazar (Kezer) was exclusively Muslim-populated, with a total population of 25 Muslim households. [41]

Kotib

We were not able to determine the geographic coordinates of this locality.

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to five Armenian households, 25 Syriac households, and two-three Muslim households. [42]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, Kotib was still home to five Armenian households and 25 Syriac households. The survey did not mention any Muslim households in the village. [43]

Tile, Til [Çattepe]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 43' 50'' N, 41° 46' 43'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village had a population of five Armenian households and eight Muslim households. [44]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village had a population of three Armenian Apostolic households, five Armenian Protestant households, five Syriac households, and 10 Muslim households. [45] Tile was the only village in the sub-district of Sghert that had an Armenian Protestant population on the eve of the Armenian Genocide.

Khoshenan, Khoushenan [Yağmurtepe]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 56' 51'' N, 41° 52' 31'' E

Khoshenan was one of the larger Armenian-populated villages of the sub-district. It is the only village of Sghert that is listed as having an Armenian population in all three of the 1878, 1902, and 1913 surveys.

According to the 1878 Devgants survey, the village was home to 32 Armenians. [46]

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village had a population of 12 Armenian households and 20 Muslim households. [47]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, Khoshenan was exclusively Armenian-populated, home to 13 Armenian households. [48]

Huseyni, Husenik [Aydemir]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 48' 31'' N, 41° 45' 3'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to five Armenian households and 10 Muslim households. [49]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to two Armenian households, three Syriac households, and four Muslim households. [50]

1) G. Sassouni, BadmoutyunDaroniAshkharhi [HistoryoftheLandofDaron], Beirut, Central Executive Board of the Daron-Darouperan Compatriotic Union, Sevan Press, 1956.

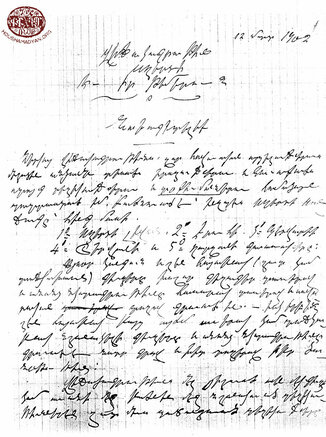

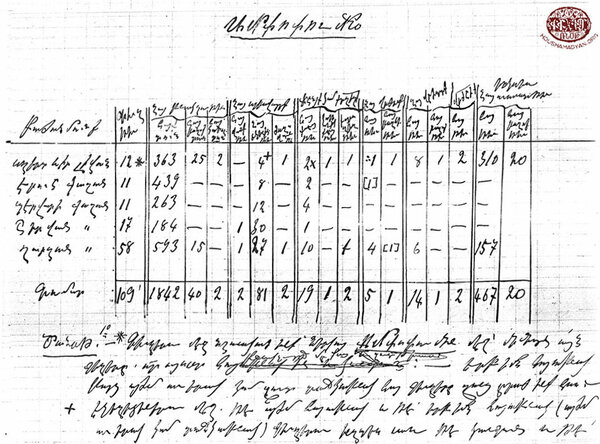

2) The title page and data table of the 1902 Sghert Prelacy demographic survey (Source: National Archives of Armenia, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856).

3) S. M. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [The Western Armenian World], New York, A. Y. Leylegian Press, 1947.

Djeffen, Djafan [Tulumtaş]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 46' 14'' N, 41° 43' 47'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to three Armenian households and eight Turkish households. [51]

The 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population. The survey noted that the village had a population of five Syriac households and 30 Muslim households. [52]

Belek, Beleke

We were not able to determine the geographic coordinates of this locality.

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to four Armenian households and 30 Muslim households. [53]

The 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population. The survey noted that the village had a population of four Syriac households and 14 Muslim households. [54]

Bekend [Beykent]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 52' 54'' N, 41° 41' 5'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, Bekend had a population of three Armenian households, five Chaldean households, and 50 Muslim households. The survey noted that in 1901, 8-10 Armenian households had fled to the village of Ayndar. [55]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to 10 Armenian households, 10 Chaldean households, and 20 Muslim households. [56] The significant increase in the Armenian population between 1902 and 1913 was most probably due to the return of refugees from Ayndar.

Brhour, Berhourk, Prhour, Prhourigs [Aktaş]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 57' 12''N, 41° 48' 29'' E

According to the 1878 Devgants survey, Brhour was home to 17 Armenians. [57]

The 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was exclusively Muslim-populated, with a total population of 25 Muslim households. [58]

Degela [İnkapı]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 59' 39'' N, 41° 53' 26'' E

The 1878 Devgants and 1902 Sghert Prelacy surveys did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to four Armenian households and four Muslim households. [59]

Dershimsh

We were not able to determine the geographic coordinates of this locality.

The 1878 Devgants survey and 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village had a population of two Armenian households and six Chaldean households. [60]

Duhok, Dihok [Oluk]

Geographic Coordinates: 37° 56' 30'' N, 41° 51' 37'' E

The 1878 Devgants survey did not list this village among those with an Armenian population.

According to the 1902 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village was home to five Armenian households and 8-10 Muslim households. A “half-ruined” church also stood in the village. [61]

According to the 1913 Sghert Prelacy survey, the village had a population of two Armenian households. [62]

Surveys of the Armenian population of the sub-district of Siirt/Sghert from 1878 to 1914

Below, we present a table that summarizes the figures provided by the 1878 Devgants survey and 1902 and 1913 Sghert Prelacy surveys. As the 1902 and 1913 surveys only counted the numbers of households, the total population for each locality was calculated by assuming a household size of eight individuals.

# | Locality | 1878 – Devgants | 1902 – Sghert Prelacy | 1913 – Sghert Prelacy | ||

Individuals | Households | Individuals | Households | Individuals | ||

1 | City of Sghert | 2,400 | 527 | 4,216 | 489 | 3,912 |

2 | Aynmilk | 24 | 5 | 40 | - | - |

3 | Ayndar | - | 10 | 80 | 3 | 24 |

4 | Avte | - | 6 | 48 | - | - |

5 | Kazar | 16 | - | - | - | - |

6 | Kotib | - | 5 | 40 | 5 | 40 |

7 | Tile | - | 5 | 40 | 15 | 120 |

8 | Khoushenan | 32 | 12 | 96 | 13 | 104 |

9 | Huseyni | - | 5 | 40 | 2 | 16 |

10 | Djeffen | - | 3 | 24 | - | - |

11 | Belek | - | 4 | 32 | - | - |

12 | Bekend | - | 3 | 24 | 10 | 80 |

13 | Brhour | 17 | - | - | - | - |

14 | Degela | - | - | - | 4 | 32 |

15 | Dershimsh | - | - | - | 2 | 16 |

16 | Duhok | - | 5 | 40 | 2 | 16 |

| Total | 2,489 | 590 | 4,720 | 545 | 4,360 |

- [1] T. Kh. Hagopian, Badmagan Hayasdani Kaghakneru [The Cities of Historic Armenia], Yerevan, Hayasdan Press, 1987, p. 226. Sghert is mentioned in ancient Syriac records (8th century BCE) as Ziqirtu (source: https://virtual-genocide-memorial.de/region/the-six-provinces/bitlis-vilayet/sancak-slirt/).

- [2] Tahir Sezen, Osmanli Yer Adlari, Ankara, 2017, p. 683.

- [3] Ibid.

- [4] Birken Andreas, Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches, Wiesbaden, Dr. Ludwig Reichert verlag, 1976, p. 184.

- [5] Sezen, Osmanli Yer Adlari, p. 666.

- [6] J. MacCarthy, The Arab World, Turkey and the Balkans, 1878-1914. A Handbook of Historical Statistics, Boston, G. K. Hall, 1982, p. 21. Kemal H. Karpat, Ottoman Population 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics, Wisconsin, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985, p. 174. For the land areas of the sub-districts, see Маевскiй, В. Т., Военно-Статистическое описанiе Ванскаго и Битлисскаго вилаетовъ, Тифлисъ, Типографiя Штаба Кавк. воен. окр., 1904, pp. 12-13.

- [7] Archbishop M. Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin yev ir Badmoutyune, Vartabedoutyune, Varchoutyune, Paregarkoutyune, Araroghoutyune, Kraganoutyune, ou Nerga Gatsoutyune [The Armenian Church and its History, Priesthood, Administration, Reforms, Rituals, Literature, and Present State], Constantinople, published by V. and H. Der-Nersessian, 1911, pp. 261-262. 1904Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1904 Complete Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, pp. 374-375. For more on the organization and administration of the Sghert diocese, see A. Alboyadjian, “Arachnortagan Vidjagner” [“Jurisdiction of Dioceses”], 1908 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1908 Complete Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1908, pp. 313-315 and p. 346.

- [8] Salnames were official yearbooks published by the central and provincial Ottoman authorities, which contained detailed information on the administrative divisions, demography, economy, and finances of the Ottoman Empire and/or its specific administrative divisions.

- [9] Маевскiй, Военно-статистическое описанiе Ванскаго и Битлисскаго вилаетовъ. Статистическiй очеркъ, p. 222; Ibid., Отдҍлъ приложенiй, pp. 140-141.

- [10] G. Sassouni, Badmoutyun Daroni Ashkharhi [History of the Land of Daron], Beirut, Central Executive Board of the Daron-Darouperan Compatriotic Union, Sevan Press, 1956, p. 361.

- [11] The letter dated 13 December 1913, from Father Kevork Nalbantian, interim prelate of the Sghert Diocese, to the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate. The letter was sent alongside the 1913 demographic survey of the Sghert Diocese (AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 31).

- [12] Pagheshtsi, “Pagheshi vidjagu godoradzen verch” [“The situation in Paghesh after the massacres”], Hunchak, the Central Organ of the Hunchak Party, year 9, number 2, 31 January 1896, p. 12.

- [13] “Hayasdanyayts Yegeghetsin Dadjgahayasdanoum” [“The Armenian Church in Ottoman Armenia”], Ararat Monthly (Echmiadzin), year 29, February 1896, pp. 89-90.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Arisdages Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878 t. [A Visit to Armenia in the Year 1878], Yerevan, Printing House of the Science Academy of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1985, pp. 114-117 (figures relating to the Sghert sub-district) and pp. 126-127 (for additional information).

- [16] Ibid., p. 114.

- [17] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun” [“Survey of Sghert and its Parishes”], National Archives of Armenia (hereafter NAA), f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 1-14.

- [18] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 2-4. The survey noted that according to official Ottoman figures, the city had an Armenian population of 300 households (ibid., p. 2).

- [19] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 63-78. For information specific to the Sghert sub-district, see ff. 63-65. As we have already mentioned, the survey was sent to Constantinople on 14 December 1913.

- [20] Generally, Protestants were listed in Ottoman and Armenian surveys as a single category, without additional information regarding their nationality. However, the great majority of Ottoman Protestants, if not all, were Armenian.

- [21] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 63-65.

- [22] Raymond H. Kévorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du genocide [The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide], Paris, Editions d’Art et d’Histoire ARHIS, 1992, pp. 502-203.

- [23] Vital Cuinet, La Turquie d’Asie [Asian Turkey], volume 2, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1891, p. 600. These figures, provided by Vital Cuinet, were used by A-To, and following A-To’s example, by Garo Sassouni (see A-To, Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzurumi Vilayetneru [The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis, and Erzurum], Yerevan, Cultura Printing House, 1912, p. 153; and Garo Sassouni, Badmoutyun Daroni Ashkharhi, p. 362).

- [24] Маевскiй, Военно-статистическое описанiе Ванскаго и Битлисскаго вилаетовъ, Статистическiй очеркъ, p. 22; Ibid., Отдҍлъ приложенiй, p. 140.

- [25] Karpat, Ottoman Population 1830-1914…, p. 174.

- [26] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, p. 114. Also see Y. M., “Namag Sghertits” [“Letter from Sghert”], Artsakank Literary and Political Periodical, Tbilisi, year 1, number 9, 18 April 1882, p. 136.

- [27] Cuinet, La Turquie D’Asie, p. 600.

- [28] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 1-2

- [29] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 63.

- [30] Kévorkian and Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman…, pp. 502-503.

- [31] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan, p. 90. Teotig’s method was emulated by S. Karayan, who assumed an average size of seven individuals per household. This formula yielded a total population of 3,500 Armenians (Sarkis Y. Karayan, Armenians in Ottoman Turkey, 1914: A Geographic and Demographic Gazetteer, London, Gomidas Institute, 2018, p. 2018). Also using Teotig’s method, Kegham Patalian estimated the Armenian population of the city of Sghert to be 500 households (Kegham Patalian, “Arevmdyan Hayasdani badmajoghovrtakragan ngarakiru Medz Yegherni nakhorein. Mas yoterort. Bitlisi nahanki harav-arevelyan kavarneru” [“The historical-ethnographic character of Western Armenia on the eve of the Armenian Genocide. Seventh part. The south-eastern districts of the province of Bitlis”], Vem Pan-Armenian Review, year 8 (14), number 4 (56) (October-December 2016), p. XIX.

- [32] S. M. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [The Western Armenian World], New York, A. Y. Leylegian Press, 1947, p. 672.

- [33] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, p. 114.

- [34] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [35] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 63.

- [36] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [37] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64.

- [38] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [39] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 63.

- [40] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, p. 114.

- [41] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64.

- [42] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [43] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64.

- [44] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [45] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64.

- [46] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, p. 114.

- [47] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [48] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64.

- [49] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [50] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 65.

- [51] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [52] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64

- [53] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [54] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 63.

- [55] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [56] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 65.

- [57] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan, p. 114.

- [58] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 64.

- [59] Ibid.

- [60] Ibid.

- [61] “Vidjagakroutyun Sgherti yev ir Temeroun,” NAA, f. 412, l. 1, c. 1856, sh. 4.

- [62] AGBU Nubarian Library Archives, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 65.