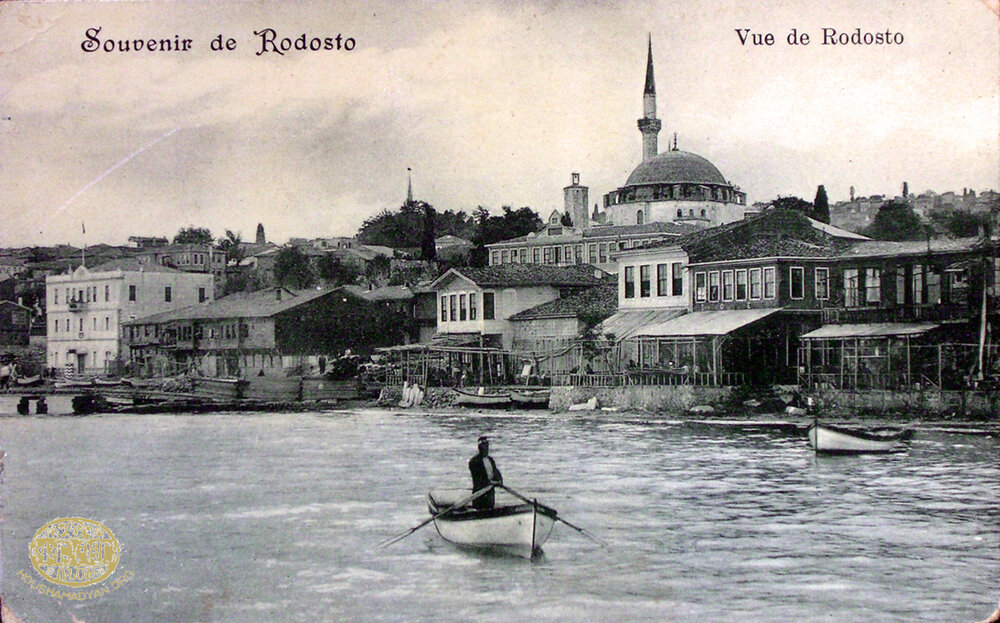

Rodosto/Tekirdagh – Churches

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 28/01/21 (Last modified 28/01/21) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

It is believed that Armenians first settled down in the Rodosto area in the early 17th century. These Armenians were natives of Kemakh (Gamakh), Sivas (Sebasdia), Erzindjan (Yerznga), Kayseri (Gesaria), and Divrig. They had been forced to flee their homes to escape the endless wars between the Safavids and the Ottoman forces, as well as the violence unleashed by the Djelali rebellions. They reached the European section of the Ottoman Empire in 1606-1607. Most probably, they first settled down in the city of Rodosto, then scattered to the towns and villages in the surrounding area, including Chorlou, Gelibolu/Gelipoli/Gallipoli, etc. Although some of these refugees returned to their homes a few years later, a significant number of them established permanent residence in and around Rodosto. [1]

As for Chorlou Armenians, their origins have been recorded in the local oral history. It is said that during the reign of Sultan Suleiman I (1520-1566), when the decision was made to construct the Suleimani Mosque in Chorlou, masons were sent to the city from Constantinople, and these masons were natives of Van. They became the first Armenians to settle down in Chorlou. [2]

The seat of the prelacy that served this territory was located in the city of Rodosto. The diocese included the cities of Rodosto, Chorlou, Dardanelles (Chanakkale), Malkara, Ezine, Silivri, and Gelibolu. [3]

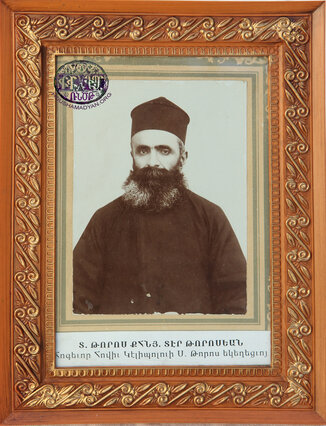

In his book, Sarkis Pachadjian provides a list of the prelates of the Rodosto Prelacy. The first among them was Father Hagop Oulnetsi (“from Ouln,”in the area of Zeytun). He was succeeded by Krikor Taranaghtsi. They were followed by Father Sarkis Tekirdaghtsi, Archbishop Apraham Gredatsi (prelate from 1709 to 1734), Archbishop Sarkis Sarafian, Archbishop Hagop Hovnanian, Archbishop Arakel Bayazidtsi (prelate from 1816 to 1831), Hagop Srpazan, Archbishop Tateos (prelate from 1847 to 1870), Senior Priest Yeznig Abahouni, Archbishop Madteos Izmirlian (prelate from 1873 to 1876), Bishop Nerses Kevorkian Tekirdaghtsi (prelate from 1877 to 1888), Bishop Hmayag Timaksian (prelate from 1889 to 1893), Senior Priest Partoughimeos Baghdjian (prelate from 1894 to 1898), Senior Priest Hovsep Ayvazian (prelate from 1898 to 1900), Bishop Nerses Aslanian (prelate from 1901 to 1903), Senior Priest Vahridj Shahlamian (prelate from 1904 to 1906), Bishop Arisdages Vankian (prelate from 1907 to 1908), Senior Priest Kevork Aslanian (prelate from 1910 to 1914), and Senior Priest Yervant Perdahdjian (prelate from 1920 to 1922). [4]

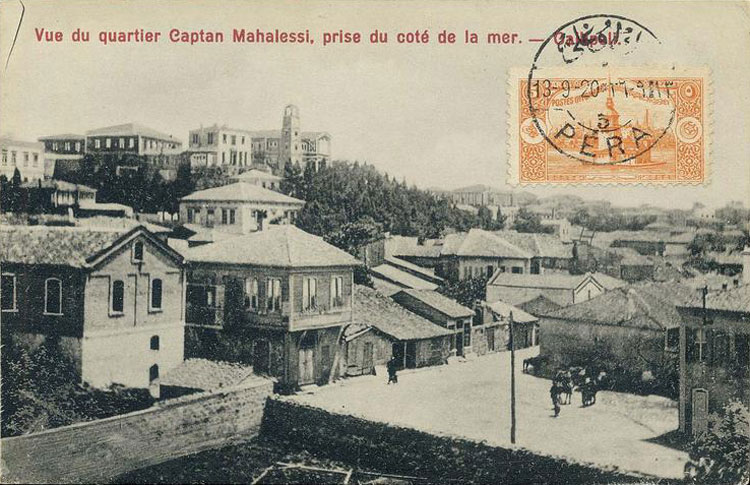

Rodosto/Tekirdagh

Approximately 15,000 Armenians lived in this city, alongside the Turkish, Greek, and Jewish communities. The total population of the city was about 30,000.

From Krikor Taranaghtsi’s book, we learn that the settlement of Armenians in the city had not been a peaceful process. He writes that the arrival of Armenians engendered a wave of discontent among the city’s Turks and Greeks. In fact, these two communities sent a joint petition to the Ottoman authorities, asking that the Armenians be moved elsewhere. It was also said that in 1620, the marriage of an Armenian youth to a Greek girl stirred conflict between the Armenian and Greek communities in Rodosto. The resulting unrest saw Greeks destroying vineyards belonging to the city’s Armenians. In 1629, it was the turn of the Turkish mob to attack the city’s Armenian and Greek neighborhoods. In the ensuing violence, the city’s Greek church was damaged, and the newly built Armenian Holy Archangel Church was completely destroyed. [5]

The Holy Archangel and Saint Hovhannes Churches of Rodosto

Soon after the settlement of Armenians in the Rodosto area, the community’s spiritual leader, Father Hagop Oulnetsi, obtained a berat (official permission) from Sultan Ahmed I (who ruled from 1603 to 1617) to build a church in the city. Construction of the church ended in 1607. Khalil Pasha, a janissary and a former Grand Vizier, played an important role in the process of obtaining the berat. Armenian sources mention that he was of Armenian origin, hailed from Zeytun, and was a relation of Hagop Oulnetsi’s.

The newly built church was called the Holy Archangel. As we have already mentioned, it was destroyed by a Turkish mob in 1629. After its destruction, with the approval of the local Greek Patriarchate and thanks to the intervention of prominent local Turks, one of the city’s Greek churches, Saint Hovhannes, was handed to the Armenian community. Taranaghtsi states that all the official steps necessary for the transfer of ownership were taken by the Greek community and the government authorities. However, it is also known that Rodosto’s Greeks were opposed to this move from the very beginning. The church was located in the Greek neighborhood of the city. Often, Greeks would impede Armenians from reaching it and harass them in other ways. In 1684, this church was burned down by the city’s Greeks. [6]

The Holy Savior Church of Rodosto

As we have seen, Rodosto’s Greek community spared no effort to prevent the city’s Armenians from using the Saint Hovhannes Church as their house of worship. In view of this, even before Saint Hovhannes was burned down, the local Armenian community began planning the construction of a new church, at the site of the destroyed Holy Archangel Church. At first, a chapel was built, called the Holy Savior. However, by the time of the death of Krikor Taranaghtsi (Prelate of Rodosto) in 1643, the Holy Savior was already known as a church. Taranaghtsi was buried in the corner of the left-hand side of its narthex. Beside his grave was another gravestone, bearing the name of Senior Priest Hagop. This was probably the final resting place of Father Hagop Oulnetsi, Rodosto’s first prelate. [7]

Later, the church gained access to its own spring. In 1810, it gained access to a second spring, flowing straight out of its external wall. However, this spring originated on land that belonged to the Greek community. Sources indicate that the construction of the springhouse was performed over a single night, thus placing the Greek community and the local authorities before a fait accompli.

The Holy Savior burned down in 1881. It was rebuilt in the following year, designed by the architect Garabed Kalfa Silivritsian. A substantial portion of the funds necessary for the renovations were provided by the Rodosto Women’s Union. [8]

The Holy Savior Church was on the coast. During the term of Prelate Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian (1889-1893), the prelacy headquarters was moved from a building adjacent to the Holy King Church to a newly constructed building in the courtyard of the Holy Savior Church. [9]

The Holy King Church of Rodosto

The Holy King Church was built in 1841. Its site was previously occupied by a monastery built in 1800, and that had 80 rooms reserved for visiting pilgrims. The architect of the new church was Minas Kalfa from Constantinople, an imperial architect. It is said that the city’s Greeks, envious of the beauty of the new church, persuaded the Ottoman authorities that the church’s name, SourpTakavor [Holy King], had political connotations for the local Armenians. The government ordered construction to be halted, but the local Armenians sent a delegation to Constantinople and receive permission to resume work.

The Holy King Church sustained significant damage in the 1912 earthquake, but repairs were completed in that same year.

For some time, the headquarters of the Rodosto Prelacy was located in a building in the courtyard of the Holy King Church. However, during the term of Archbishop Hmayag Timaksian (1889-1893), the prelacy moved into a new building adjacent to the Holy Savior Church. [10]

The courtyard of the Holy King Church was also the site of many political gatherings. Specifically, in 1908, after the reinstatement of the Ottoman Constitution, a rally was held there, featuring speeches by the commander of the Rodosto police force, Nihad Bey; and the principal of the Hisousian School, Kevork Mesrob. They both hailed the revolution and called for brotherhood among nations to celebrate the occasion. [11]

A few years after this rally, the Balkan War started, and in October 1912, Rodosto was occupied by Bulgarian forces. The stone building of the Hisousian School, adjacent to the Holy Cross Church, was used as a garrison for the Bulgarian troops. An Armenian battalion fought alongside the Bulgarian Army, under the command of Antranig Ozanian and Karekin Njteh. The two commanders, with their 300 soldiers, visited Rodosto and received communion at the Holy King Church on Christmas. The entire Armenian population of the city came out to greet them on that day. The Armenian battalion was accompanied by Colonel Protogeroff of the Bulgarian Army. At the entrance of the Holy King Church, the Armenian marching band played the then-Bulgarian anthem, Shumi Maritsa, and the Armenian anthem, Mer Hayrenik. Then, mass was held in the church, after which Karekin Njteh made speeches in Armenian and Bulgarian, and the church’s boys’ and girls’ choirs sang national songs. Afterwards, the crowd gathered in the courtyard, where Colonel Protogeroff, in the name of the Bulgarian king, awarded crosses of bravery to the Armenian soldiers, while the Armenian marching band once again played the Bulgarian national anthem. The first of the Armenians to receive the medal was Antranig Ozanian, and as he received the decoration, the band played Iprev Ardziv, a song dedicated to him. [12]

The Holy King Church was a particularly popular destination on the Feast of the Assumption/Dormition of Mary. This holiday held special significance for Rodosto, and it was also the feast day of the church. Every year, on that day in the middle of August, thousands of pilgrims would crowd into Rodosto. The celebrations culminated with the public display of the Sourp Pever (Holy Nail), the most important relic kept at the Holy King Church. According to tradition, it was the nail that had affixed the sign reading “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” on Christ’s cross. The name of the church, the Holy King, was inspired by this relic. [13]

The Holy King neighborhood had its own Armenian cemetery. [14]

Clergymen known to have served in the Holy King Church include:

- Father Mampre Kirazian (1847-1916).

- Father Khoren Djamdjian (1866-1931). From 1910 to 1915, he was the locum prelate of the Rodosto Prelacy.

- Father Arisdages Malakian (born in 1856).

- Father Tateos Chilingirian.

- Father Partogh Takumdjian (1875-1941).

- Father Kegham Yulduzian (1871-1940).

- Father Tateos Poryadjian (1879-1952). He was deported to Der Zor in 1915, but survived.

- Father Nerses Ghazarosian. [15]

The Holy Cross Church of Rodosto

The Holy Cross neighborhood had once been the chiftlik (farm) belonging to a Turkish pasha, where poor Armenian farmers worked the land. In later years, the site grew into one of the city’s neighborhoods. It was known to the city’s Armenians as Holy Cross (Sourp Khach), and to the city’s Turks as Chiflikeonu, a name that had originated with the area’s original status as a chiftlik.

In 1804, the neighborhood constructed its own church, the Holy Cross, built of wood. The structure had not been sanctioned by the authorities. The permit was finally obtained in 1808, thanks to Boghos Agha Dilanian, one of the preeminent residents of the neighborhood. The imperial berat of the church was signed by Sultan Mahmud II (who reigned from 1808 to 1839). An anecdote has been traditionally recounted about these events: Boghos Agha appeared before the Sultan with his petition in hand, and a sack slung over his shoulder. In the sack were an axe and a length of rope. The petition read:

İstediğimiz kilise

İzin verilmez ise

Darılır Hazreti İsa.

[What we want is a church

And if we are not granted our wish,

Isa [Christ] will be displeased with you.]

Boghos Agha presented this petition to the Sultan and placed the items in his sack before him. When the Sultan asked for an explanation, Boghos Agha replied that he was offering the Sultan three choices: to behead him with the axe, to hang him with the rope, or to grant him the berat. The Sultan chose the third option… This anecdote, incidentally, illustrates the significance of the berat for the local Armenian community. Boghos Dilanian died in 1815 and was buried at the front of the right-hand side of the narthex of the Holy Cross Church. [16]

In subsequent years, as the Armenian population of the Holy Cross neighborhood grew, the church could no longer accommodate the large number of worshippers. In 1843, work began on its expansion. Unfortunately, during construction, the structure collapsed. Construction of a new church building began in 1847, designed by architect Minas Agha, from Constantinople. Construction ended in that same year. Funding for this project was provided by Rodosto Armenians living in Constantinople, as well as descendants of Kayseri and Moundjousoun Armenians. The names of the donors were engraved on the church door. [17]

The Holy Cross neighborhood had its own Armenian cemetery. [18]

The following clergymen are known to have served in the Holy Cross Church:

- Father Vrtanes Adzrigian-Pashalian (1854-1923).

- Father Hagop Nazarian (born in 1867). In the years of the Genocide, he was deported to Syria, but survived.

- Father Nerses Nazarian (1847-c. 1920).

- Father Kapriel Begian, who was deported and killed during the Genocide. [19]

The grave of Archbishop Hagop Hagopian, one of the prelates of the Rodosto Diocese, was in the courtyard of the Holy Cross Church. [20]

Armenian Clergymen Born in the Rodosto Area

Father Andon Tekirdaghtsi (died in 1715), Father Arakel Mazloumian (died in 1891), Archbishop Sarkis Der Sarkisian (1872-1932), Father Kevork Tourian (born in 1872, killed in 1915), Khachadour Sdepanian (Silistretsi), Father Khoren Portoukalian (died in 1902), Father Ghevont Bekarian, Archbishop Hagop Tekirdağtsi, Father Hagop Boloutsi, Archbishop Haroutyun Tekirdaghtsi (died in 1793), Archbishop Sarkis Sarkisian (born in 1871), Father Vartan Hagopian (1849-1920), Father Vagharshag Boghosian (1835-1905), and Father Yeremia Chorloutsi (born in 1796). [21]

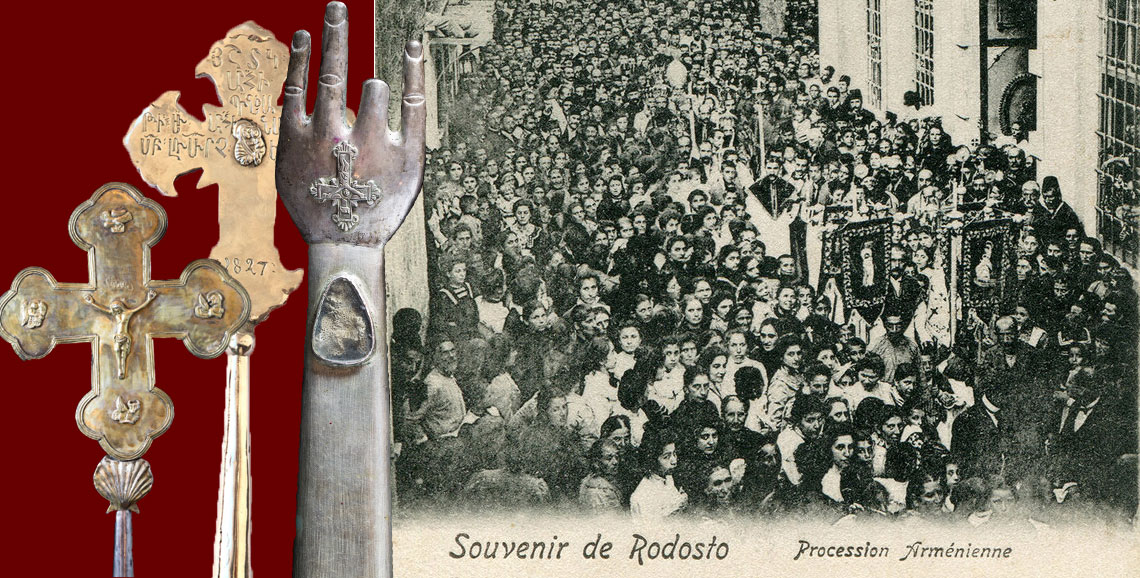

The Treasures of the Churches of Rodosto

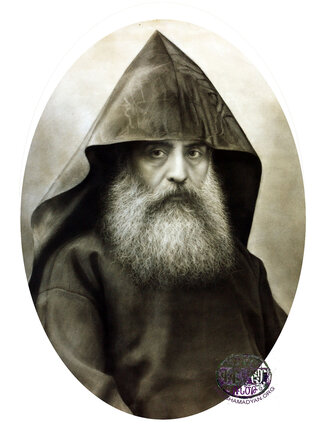

The churches of the Rodosto area no longer stand. They have been demolished, and the fervent religious life that once thrived within their walls has disappeared. However, some of the treasures of these churches were rescued by local Armenians who smuggled them out of the country and to their new homes. This was especially true of the treasures of the churches of the city of Rodosto and the Saint Toros Church of Gelibolu/Gelipoli/Gallipoli.

We know that throughout the Ottoman Empire, including in Rodosto, the treasures of Armenian churches were plundered during the years of the Genocide. But some of these items were spared the worst and were preserved by devout Armenians. After the Armistice of 1918, survivors of the massacres returned to their homes and began a new life in Rodosto, this time under Greek occupation. The hidden treasures of Rodosto’s churches were unearthed and religious life resumed. In late 1922, the Turkish armies recorded significant and successive successes on the Greco-Turkish front, forcing the Greek armies to retreat. This resulted in the exodus of the city’s Greeks and Armenians. The Armenian refugees chose two primary destinations – Bulgaria and Greece. They once again smuggled out the treasures of their churches, particularly those of the Holy King Church, but also those of the Holy Cross and Holy Savior churches. These items were taken to Bulgaria, packed in 13 boxes, and kept in the Saint Kevork Church of Phillipolis/Plovdiv. Some items were moved to Echmiadzin in 1947. [22]

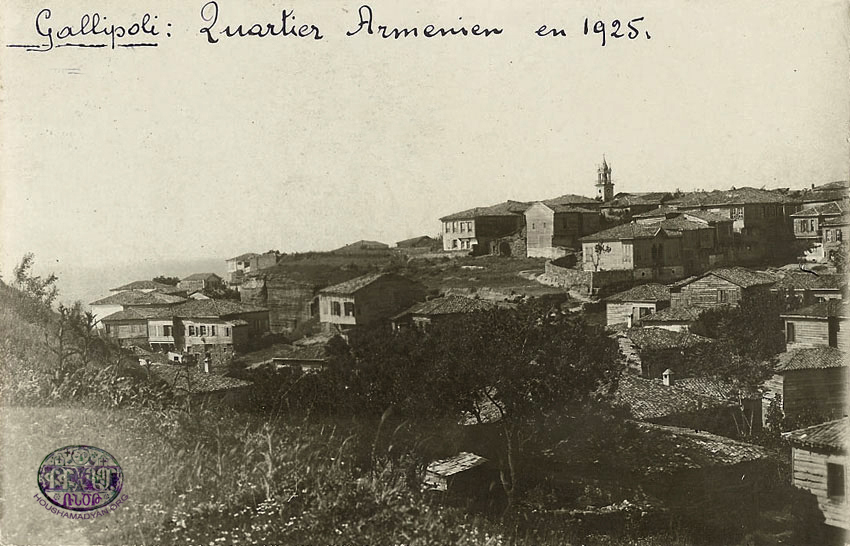

The treasures of the Saint Toros Church of Gallipoli were also saved thanks to a similar effort. Specifically, in 1922, during the mass emigration of the Armenian population from the area, each household assumed responsibility for saving one item from the church. The city’s Armenians boarded a ship together and took the road of deportation. Their first stop was the island of Cephalonia. Later, most of them moved to Kokkinia (Nikaia), near Pireas, where a large community of Armenian and Greek refugees had already settled down. The rescued treasures of the Saint Toros Church found a new home in the Saint Hagop Church, built by this immigrant community. They are still kept there today. [23]

The Martyr’s Pilgrimage Site of Rodosto

This was the name given to a grave located near the Armenian Holy King neighborhood. It consisted of a modest hut, which sheltered the final resting place of an Armenian youth named Sdepan. It was a popular destination for both Armenian and Turkish pilgrims, who specifically visited it hoping to be cured of their ailments.

According to legend, Sdepan was a youth who had spent his life in the service of the Armenian church. In 1699, when he was 23 years old, he had a dispute with one of the local ecclesiastic leaders, after which he converted to Islam. But he quickly rued this decision and returned to his original faith. This action, unfortunately, was considered illegal. He was tried, and the judge found him guilty of insulting the Muslim faith. Sdepan was sentenced to prison. Despite the torture that he endured, Sdepan remained steadfast and did not convert back to Islam. Eventually, the authorities beheaded him and tossed his body into the street. But at night, the locals noticed that an ephemeral light shone out of the young man’s lifeless corpse, which prompted the Turkish authorities to demand that the Armenian community retrieve and bury the body. Sdepan was buried near the Armenian cemetery, and his grave became a pilgrimage site shortly thereafter. [24]

The Evangelical Church of Rodosto

There were two Protestant meetings halls in Rodosto – one in the Holy King neighborhood, and the other in the Holy Cross neighborhood. According to information from 1903, the city’s Protestant community did not yet have architectural blueprints for the construction of their church, and both meetings halls were spacious. The community consisted of about 100 individuals.

We have no information regarding the first-ever Armenian Evangelical church in Rodosto. But we know that the second such church was built in 1863. This project was spearheaded by The Very Reverend Boughdanian. It was a rented residence, located in the Holy King neighborhood. A year later, another residence was purchased, and the community’s church and school were moved into it. The missionary association provided much of the funding needed to operate the two Evangelical churches of the city. [25]

Boughdanian served as the spiritual leader of his community until 1870. He was succeeded by The Very Reverend Hovhannes Sdepanian, who served in Rodosto until 1898. His term coincided with a significant growth in the itinerant book trade – the community would dispatch its members to the nearby cities and villages to sell the Holy Book and proselytize. After Sdepanian’s departure from the area, the lay leader of the community, M. H. Kouzou Kebabian, led the services in the two churches. During this period, while the community lacked a permanent minister, many traveling clergymen visited its churches. In December 1901, Reverend Aristidis Moumdjiadis came to Rodosto. He was a Rodosto Greek, had graduated from the theological seminary of Marzvan/Merzifon, and spoke Armenian. Reverend Moumdjiadis also preached in Greek in the First Evangelical Church. [26]

Later, The Very Reverend Sarkis Manougian assumed leadership of the community, and served in this capacity until 1915. [27]

The Catholic Church of Rodosto

We know very little about this community. We simply know that an Armenian Catholic Church stood in the Holy King neighborhood, and that the local Armenian Catholic community consisted of a few households.

Chorlu

The Saint Kevork Church of Chorlou

Approximately 2,000 Armenians lived in Chorlou.

Presumably, the city’s Saint Kevork Church was built in the 17th century, as the grave of an Armenian clergyman, bearing the date 1692, was located on the church grounds. It is more probable that the church was a simple chapel in the early years of the 17th century and was later expanded into a church. This leads us to conclude that the berat issued by Sultan Selim III (who reigned from 1789-1807) and kept in the church, dated 1789, was in fact the original permission for its construction. In that same year, the local Armenian community received a second official permission, this time from Yusuf Pasha, the Grand Vizier, which allowed Armenians to collectively establish residence in the neighborhood around the church. Construction of the Saint Kevork Church began in 1791 and ended in 1796.

The berat issued by Sultan Selim III was kept in the church, and constituted the imperial edict sanctioning the establishment of the Armenian community in Chorlou. [28]

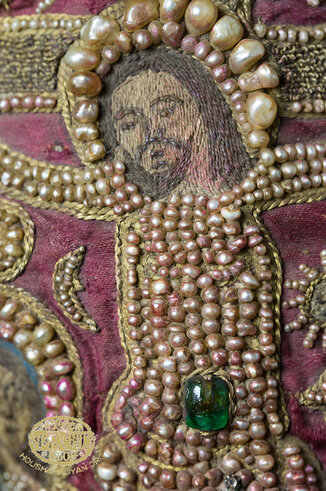

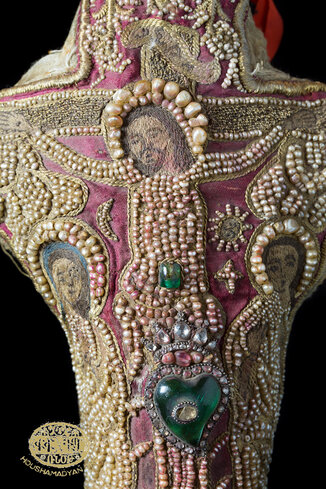

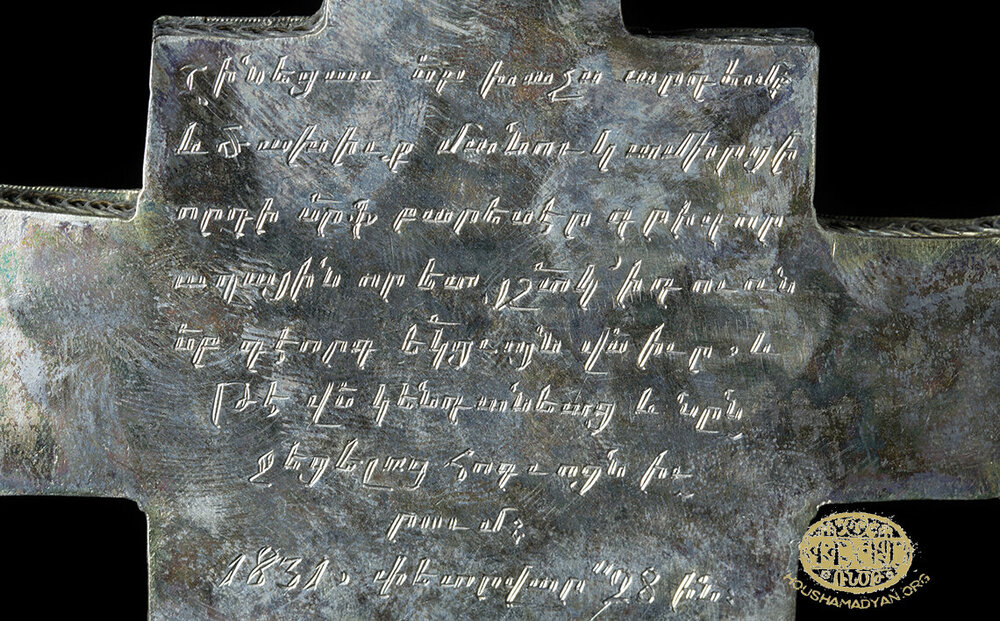

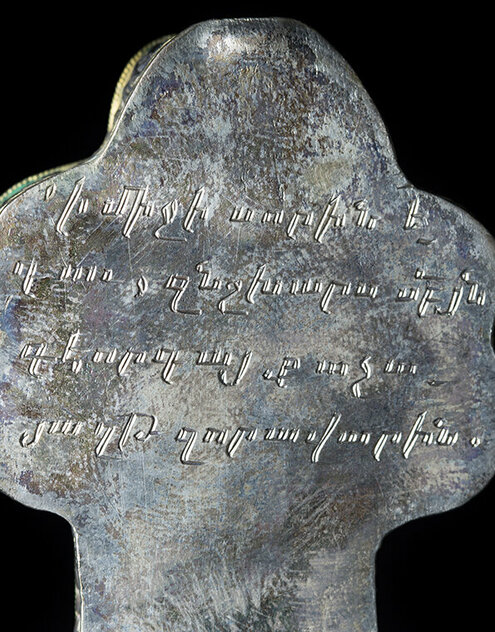

A silver cross. The back of the cross indicates that it was a gift to the Saint Kevork (George) Church by Krikor Agha (son of Manoug Amira), and was presented to the church on February 28, 1831. It is also noted that the cross bears relics of Saint George, the “Unconquerable Warrior.” In the Rodosto area, the communities of Chorlou, Silivri, Ezine, and Dardanelles all had churches named Saint Kevork. This cross came from one of those churches, but we cannot determine which. It is currently kept at the Saint Kevork Church of Plovdiv. Photographed by Raffi Youredjian.

After its construction, the Saint Kevork Church became an important pilgrimage site for the area’s Armenians. Previously, Rodosto’s Armenians would celebrate the Feast Day of Saint Kevork, locally known as Khederellez/Hıdırellez, by visiting the Ay-Yorgi Greek Church of Ereğli. But after its construction, Saint Kevork became the primary pilgrimage site for the locals. On that holiday, pilgrims would arrive in chariots from Rodosto and stay for an entire week. To accommodate these pilgrims, an inn was built behind the church with more than 30 rooms. [29]

Arshag Alboyadjian writes that once, a building stood beside the Saint Kevork Church that housed the prelacy. By the end of the 19th century, the building had been vacated and had been rented out. It is unclear which prelacy this refers to, as the prelacy of the diocese was headquartered in the city of Rodosto. Was it headquartered in Chorlou for some time? Unfortunately, we are unable to answer this question. Alboyadjian adds that the building had been constructed in the 1860s, and notes that previously, the prelacy had been headquartered in another building in the city. This building had been turned into a garrison for passing Sardinian troops during the Crimean War (1853-1856) and had burned down in 1856. [30]

In his article published in 1901, Alboyadjian provides a detailed description of the Saint Kevork Church. He writes that it was a dark and low structure with many columns. The altar table was made of ebony, with a mother-of-pearl inlay. The walls of the church were covered in porcelain tiles, each featuring the sign of the cross. At the top corner of each tile was the phrase “Servant of Christ,” and at the bottom was the name of a benefactor. As a result, the walls of the church displayed a large number of names. Alboyadian writes that on the left-hand side of the church, a small altar table bore an inscription that provided an explanation of these porcelain tiles. It stated that the names on the tiles belonged to master and apprentice tailors from Chorlou and Tekirdagh (Rodosto). In fact, names of other individuals also appeared. These tailors worked in Constantinople and lived in the Kelle Kese Khan [inn]. Alboyadjian adds that this khan was destroyed in the 1894 earthquake. The porcelain tiles were gifts that that these devout Armenians had crafted and had presented to the Saint Kevork Church in 1815. [31]

Alboyadjian also provides a great deal of information on the church’s treasures. Its walls were decorated with a number of paintings, including several that portrayed episodes of the life and trial of Saint Yeghia (the prophet Elijah). The main altar featured icons of the Holy Virgin and Saint Sdepanos. The church also housed a collection of manuscripts. One of these was an expansive, handwritten djashots [lectionary], which included several chronicles, the oldest of which dated from 1407. It is presumed that this manuscript was brought to Rodosto from Amasia. [32] The collection of manuscripts also included a Bible from 1649 and two Mashdots [ritual books]. One of the latter was written in 1833, in fine and elegant handwriting. As of the time of Alboyadjian’s visit, this Mashdots was still being used during baptismal ceremonies. The other Mashdots had been a gift that the church had received in 1833. [33]

In 1893, Saint Kevork’s belfry was built, featuring metallic pillars. [34]

Clergymen known to have served in the Saint Kevork Church include:

- Father Nshan Der-Antreasian, who served until 1915 as the last priest of the church, and who had been ordained in 1907. Like the rest of the Armenian population of Chorlou, he was deported to Nicomedia/Izmit, and from there into Syria. He was killed in Der Zor.

- Father Kevork Tavitian.

- Father Dionysius Arsenian. [35]

Another important feature of the religious landscape of Chorlou were the tombstones of the city’s cemetery. The inscriptions carved on them were in Turkish, as the Armenian population of Chorlou spoke Turkish as its primary language. [36]

Silivri

The Saint Kevork Church of Silivri

Approximately 1,000 Armenians lived in Silivri on the eve of the Genocide. Clergymen known to have served in this church include:

- Father Khoren Djamdjian, who served as a priest in the village from 1900 to 1910.

- Father Arisdages Adzrigian.

- Father Vrtanes Adzrigian.

- Father Garabed Dishlian, who was deported during the Genocide and was killed in Der Zor. [37]

Ezine

The Saint Kevork Church of Ezine

The number of Armenians who lived in Ezine before 1915 was 670. This included the Armenian-Posha(Romani) population of two villages near the city, Kuzul and Baluklu, which had a majority Turkish population. [38]

The church was built in 1839 and underwent repairs in 1889. [39]

Clergymen known to have served in this church include:

- Father Vrtanes Adzrigian.

- Father Mesrob Torosian (born in 1866). [40]

Malgara

The Saint Teotoros Church of Malgara

Approximately 3,500 Armenians lived in Malgara on the eve of the Genocide in 1915.

Clergymen known to have served in this church include:

- Father Kevork Tavitian (born in 1872), who served as the church priest until 1915.

- Father Hovhannes Der-Mgrdichian (born in 1866). He served as a priest in Malgara until 1912, when he moved to Constantinople.

- Father Toros (surname unknown). [41]

The Father Movgim Pilgrimage Site of Malgara

This was a holy site (ayazma) located outside of the city. It was visited by pilgrims on Ascension Day. [42]

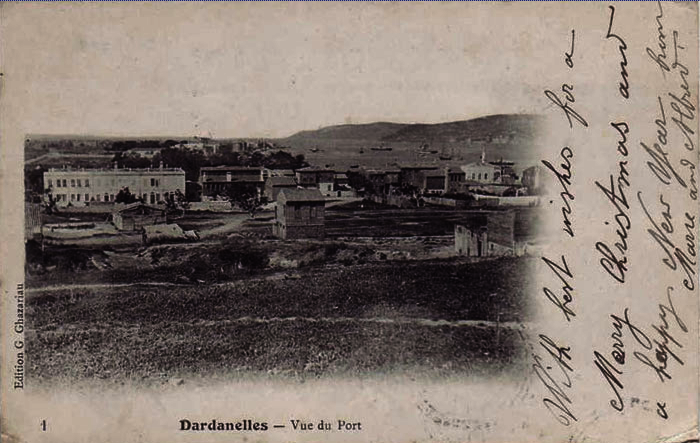

Dardanelles (Chanakkale)

The Saint Kevork Church of Dardanelles

Approximately 1,200 Armenians lived in this city. From 1909 to 1915, Father Dionis Drezian (born in 1870) served as the priest of the Saint Kevork Church. [43]

The Evangelical Community of Dardanelles

Dardanelles was home to a small Armenian Evangelical community. Its members, according to information from 1903, would gather in a home they had purchased to use as a meeting hall. The community had ties to the Evangelical Church of Rodosto. [44]

Gelibolu/Gelipoli/Gallipoli

The Saint Toros Church of Gelibolu

Approximately 1,200 Armenians lived in this city until the start of the First World War.

Clergymen known to have served in this church include:

- Father Toros Torosian.

- Father Karekin.

- Father Vartan Bedrosian. [45]

- [1] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru (Irents Antsyaln ou Nergan)” [“The Armenians of Chorlou (Their Past and their Present)”], Puzantion, 6th year, number 1554, 5/18 November 1901, Constantinople.

- [2] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru (Irents Antsyaln ou Nergan),” Puzantion, 6th year, number 1552, 2/15 November 1901, Constantinople.

- [3] Sarkis K. Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi Hayeroun 1606-1922 [Memory Book of Rodosto Armenians 1606-1922], G. Donigian Press, Beirut, 1971, p. 172; Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru (Irents Antsyaln ou Nergan),” Puzantion, 6th year, number 1561, 13/26 November 1901, Constantinople.

- [4] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, pp. 173-181.

- [5] Father Krikor Gamkhetsi, Jamanagakroutyun Krikor Vartabedi Gamakhetsvo gam Taranaghtsvo [Chronicle of Father Krikor Gamakhetsi or Taranaghtsi], Jerusalem, 1915; Sarkis K. Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, pp. 21-32.

- [6] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, p. 27 and pp. 36-37; Hayr Vartapuyr, “Mishd Gentani ou Mkhatsogh Kaghakneren Hay – Rodosto” [“The Always-Vibrant and Sprightly Armenian Cities – Rodosto”], Baykar, 13 August 1958, number 189 (16000), Boston.

- [7] Ibid., p. 38 and pp. 173-174.

- [8] Ibid., p. 38.

- [9] Ibid., pp. 179-180.

- [10] Ibid., pp. 41-42 and 179-180.

- [11] Ibid., p. 51.

- [12] Ibid., pp. 55-57.

- [13] Ibid., p. 229.

- [14] Ibid., p. 196.

- [15] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and Its Flock's Catastrophic Year of 1915], New York, 1985, pp. 415-416; Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, pp. 38-40.

- [16] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, pp. 38-40.

- [17] Ibid., p. 41.

- [18] Ibid., p. 196.

- [19] Teotig, Koghkota…, pp. 417-418.

- [20] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, p. 175.

- [21] Ibid., pp. 183-186.

- [22] Ibid., pp. 229-231.

- [23] Father Varak Hovsepian (ed.), Kokkinio S. Hagop Hayasdanyats Arakelagan Yegeghetsvo Himnatroutyan 70-Amyag, 1933-2003 [The 70th Anniversary of the Founding of the Saint Hagop Armenian Apostolic Church of Kokkinia, 1933-2003], Kokkinia, 2003, pp. 55-56.

- [24] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, pp. 197-198.

- [25] M. K., “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyunu” [“History of the Church of Rodosto”], Puragn Review, year 20, number 51, 21 December 1902, Constantinople, p. 813.

- [26] M. K., “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyunu, 1852-1902,” Puragn Review, year 20, number 7, 15 February 1903, Constantinople, pp. 135-136; M. K., “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyunu,” Puragn, year 21, number 8, 15 March 1903, pp. 155-157; M. K., “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyunu,” Puragn, year 21, number 11, 22 February 1903, p. 235; M. K., “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyunu,” Puragn, year 21, number 16, 19 April 1903, p. 311.

- [27] Teotig, Koghkota…, p. 418.

- [28] Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru…,” Puzantion, number 1554.

- [29] Ibid.; Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, p. 200.

- [30] Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru…,” Puzantion, 6th year, number 1561, 13/26 November 1901, Constantinople.

- [31] Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru…,” Puzantion, number 1554; Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru…,” Puzantion, 6th year, number 1555, 6/19 November 1901, Constantinople.

- [32] Ibid.

- [33] Alboyadjian, “Chorloui Hayeru…,” Puzantion, number 1561.

- [34] Alboyadjian, “Chorloui Hayeru…,” Puzantion, number 1555.

- [35] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Chorlouyi Hayeru (Irents Antsyaln ou Nergan),” Puzantion, 6th year, number 1564, 16/29 November 1901, Constantinople; Teotig, Koghkota…, pp. 418-419.

- [36] Alboyadjian, “Chorloui Hayeru…,” Puzantion, number 1561.

- [37] Teotig, Koghkota…, pp. 416-417 and p. 419.

- [38] Ibid., p. 421.

- [39] Ibid.

- [40] Teotig, Koghkota…, p. 417 and 421.

- [41] Ibid., p. 419.

- [42] Pachadjian, Houshamadyan Rodostoyi…, p. 180.

- [43] Teotig, Koghkota…, p. 420.

- [44] M. K., “Rodostoyi Yegeghetsiyin Badmoutyunu,” Puragn, year 21, number 11, 22 February 1903, Constantinople, p. 217.

- [45] Teotig, Koghkota…, p. 422.