Erzindjan/Erzincan/Yerzenga - Churches and Monasteries 2

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 16/12/2019 (Last modified: 16/12/2019) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Armenian Monasteries of Erzindjan

Overview

According to the list of Armenian houses of worship provided by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople to the Ottoman Ministry of Justice and Religious Denominations, there were a total of 77 Armenian churches and monasteries across Erzindjan in 1912-1913, both standing and in ruins. Of these, 24 were monasteries and 53 were churches [1].

Bishop Drtad Balian, in 1902, listed 27 monasteries across Erzindjan, both standing and in ruins [2]. Father Hamazasb Vosgian, in his work Partsr Hayki Vankere [The Monasteries of Upper Hayk], listed 34 monasteries across Erzindjan [3].

According to Father Taniel Hagopian, interim prelate of the Erzindjan Diocese from 1897 to 1905, there were nine functioning monasteries within the borders of the diocese proper. These were the Saint Giragos, the Miyavor Saint Garabed, the Dirashen Saint Nerses, the Saint Boghos-Bedros (Chakhermanou), the Shoghakat Holy Virgin, the Saint Kevork of Yergan, the Saint Hagop (Gayipos (Gabos)), the Charcharanats [Bearer of Sufferings] Saint Krikor the Illuminator (Dasag Monastery), and the Saint Nigoghos (Saint Nigoghayos) of Ptaridj [4].

Other sources also include the Avak (Saint Tateos-Partoghomeos) and Saint Krikor the Illuminator (Medz Lousavorich) in the list of Erzindjan monasteries. However, strictly according to the diocesan-administrative divisions of the Armenian Church, these institutions were located in the neighboring diocese of Gamakh [5].

Most of Erzindjan’s monasteries were located in the foothills and on the flanks of the mountains that ringed the Erzindjan Valley. They all had dominant geographic positions above the valley, and boasted rich supplies of water, fertile fields, and a temperate climate [6].

Like in other regions of historic Ottoman Armenia, Erzindjan’s monasteries were also sacred pilgrimage sites. The saints after whom the monasteries were named were thought to have the ability to heal visiting pilgrims. One was thought to heal ailments of the eye, another to heal pains of various kinds, a third to heal infertility, etc. Each monastery had its own lousaghpur, a sacred spring of frigid water flowing inside the monastery compound or nearby. The locals believed that these waters also had healing powers. In particular, those who suffered from febrile conditions believed that they would be cured if they bathed in them [7].

In the era immediately preceding the Armenian Genocide, none of the monasteries of Erzindjan had a functioning order. They were administered by boards of trustees and by the Armenian Prelacy. As a general rule, the diocesan authorities would rent out the monastery properties to married priests or sometimes lay private individuals, including peasants and farmers. These tenants, called vanabeds or vanabahs [monastery custodians], had full rights over the monastery estates, and earned all income generated from them. In exchange, they paid rent to the Prelacy. According to figures from the 1890s, the total income generated for the Prelacy from these rentals was 80 Ottoman pounds per year [8].

As for monasteries that did not own much land or property, they were usually maintained by groups representing specific industries or crafts from the city of Erzindjan. These groups would look after the monasteries and ensure that they were in good repair. In exchange, they received the right to spend their summers on the monastery grounds alongside their families. For example, the Saint Kevork Monastery of Yergan was maintained by copper workers, the Miyavor Saint Garabed by barbers [9], and Saint Giragos by commercial painters [10].

The full text of the contract signed between the board of trustees of the Dirashen Saint Nerses Monastery and its custodian has been preserved. It is an illustrative examples of the relationship between the monasteries of Erzindjan and their custodians, as well as the latter’s rights and responsibilities. The contract stipulated that the custodian was duty-bound to treat the monastery as he would treat his own home; perform all necessary maintenance and repair work not exceeding 100 kurus in cost; plant 300 willows and poplar trees; pay the emlak tax imposed on the property by the government; pay 7.5 Ottoman pounds to the board of trustees as rent; not cut any of the monastery’s trees or sell any of the its water (the monastery’s water was to be used only for its own needs); etc. In exchange, the custodian received full rights over the monastery’s property and animals, as well as any income generated from the estate. Any fees paid by visiting pilgrims for church rites were also remitted to the custodian [11].

Despite such contracts, as a general practice, many monastery custodians were much more interested in abusing their privileges for personal gain, rather than maintaining or improving monastic compounds. A contemporary observer reported: “Because the monasteries have no orders or monks, they are being destroyed by the greed of the tenants, who sometimes cut down the orchards, sell the animals, plunder the furniture and even the holy utensils, and renounce their contractual obligations to renovate and refurbish the buildings” [12].

The monasteries played the role of unique holiday destinations for the Armenians of Erzindjan, who spent their summers there as “pilgrims.” All functioning monasteries in Erzindjan had living quarters to accommodate such guests. Most monasteries had five to ten rooms, each of which could accommodate, if necessary, up to two-three families. When they ran out of space in the living quarters, pilgrims simply pitched tents on the monastery’s grounds.

The custodian shared vegetables and fruits from the monastery’s fields and orchards with the pilgrims, sometimes also providing them with milk and yogurt. In exchange, the pilgrims would bring gifts of shoes, clothing, and products of their own crafts for the custodian’s family. In addition, the visitors would make gifts of cash to the landlords, which were effectively payments for room and board [13].

Before leaving, the pilgrims would customarily slaughter an animal as a sacrifice. The ill-fated ewe or calf would always be purchased from the monastery, and the skin would be put aside for the custodian. Monastery custodians also supplemented their income with the funds raised during services (plate alms), as well as the gifts that poured in when holy relics were put on public display [14].

The monastery custodians of Erzindjan, in order to protect their interests, sought the patronage of prominent and notable Armenian community figures from the city. These patrons would advocate for the custodians within both Armenian and Ottoman institutions in exchange for gifts and the right to spend the summer months at the monasteries as guests of honor with full privileges [15].

To be the custodian of a monastery was not easy. The monasteries, usually located in distant valleys or perched on precipitous hills, far from settlements, were constantly attacked and plundered by Kurdish marauders. To confront such dangers, custodians had to possess both great courage and great diplomatic skills [16].

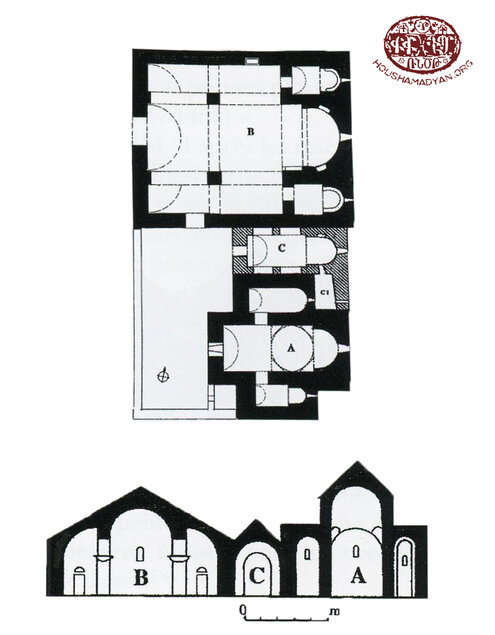

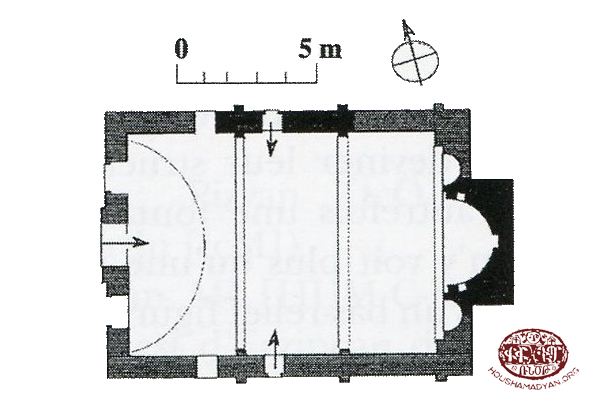

1) The sketch of the Avak Monastery’s Holy Mother of God Church.

2) A reproduction photo portraying the cross on the dome of the Holy Mother of God Church (Vank Monastery).

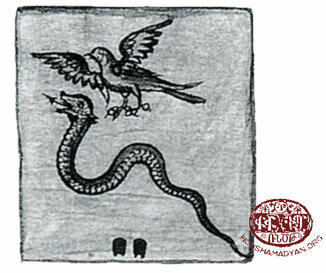

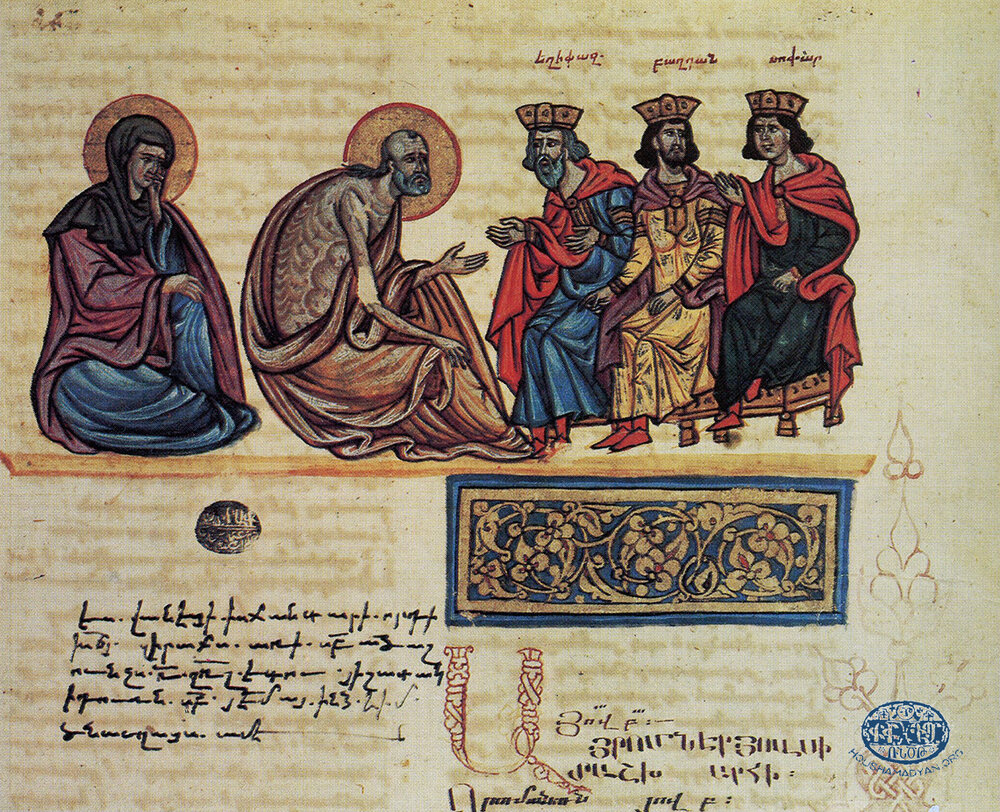

3) The picture of an “teghtap” (antidote) located in the monastery at Mt. Sebouh. A snake and dove appear. “Teghtap” (դեղթափ) is an Armenian word meaning antidote/poison neutralizer.

(Source: Jean-Michel Thierry de Crussol, Monuments arméniens de Haute-Arménie, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2005)

However, even the bravest and most diplomatic custodians did not escape the wave of violence that fell upon the district of Erzindjan during the Hamidian massacres, in October 1895. During these events, eight of the diocese’s monasteries were attacked and plundered. The custodian of the Charcharanats Saint Krikor the Illuminator Monastery, as well as the priests of the villages of Khntsorig and Gharatoush, alongside their families, were killed [17].

In the years following the Hamidian massacres, the monasteries of Erzindjan recovered only partially. Eventually, relative normalcy was restored until the Genocide and the final extermination of the area’s Armenian population.

Below, we present detailed information on the nine monasteries functioning in Erzindjan on the eve of the Genocide, as well as the three famed holy sites in the western foothills and on the western flanks of Mount Sebouh (Mount Khohanam or Manya) – the Saint Tateos-Partoghomeos Monastery (Avak Monastery), the Saint Krikor the Illuminator Monastery, (Medz Lousavorich), and the Holy Savior Monastery of Tortan, also known as the Grave of the Nine Saints.

The Holy Sites of Mount Sebouh

The Saint Tateos-Partoghomeos [Thaddeus-Bartholomew] Monastery (Avak Monastery)

The Avak Monastery was located in the western foothills of Mount Sebouh, in a dell (for this reason, it was also called Terevank). The monastery was near the Armenian-populated village of Garni (Karni). Accordingly, it was also sometimes called the Garni (Karni) Monastery [18].

According to legend, the monastery was founded by Saint Thaddeus the Apostle, who initially named it the Holy Virgin. Only later was it renamed after the apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew [19].

The monastic compound included three non-domed churches, the Saint Tateos, Holy Virgin, and Saint Garabed. It also included living quarters for monks and for visiting pilgrims, and the buildings necessary for the monastery’s economy (barn, granary, etc.). The compound was surrounded by a wall [20]. The largest of the monastery’s churches was the Saint Tateos, which was described as a beautiful, majestic, and formidable structure [21]. The wooden door of the church featured carvings of Christ and his apostles, as well as an inscription [22].

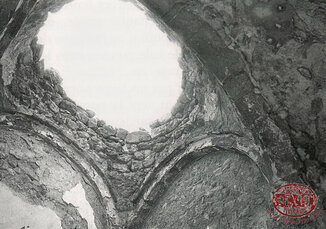

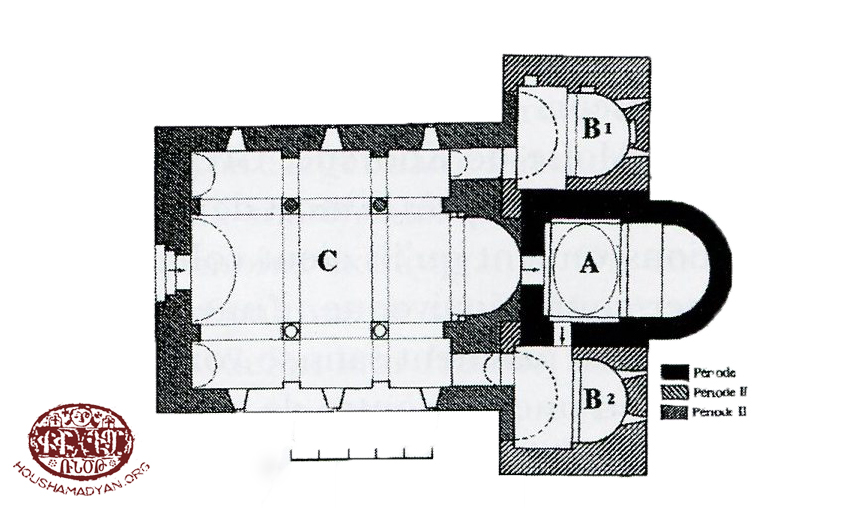

1) Interior view of the ruins of the Avak Monastery’s Holy Mother of God Church.

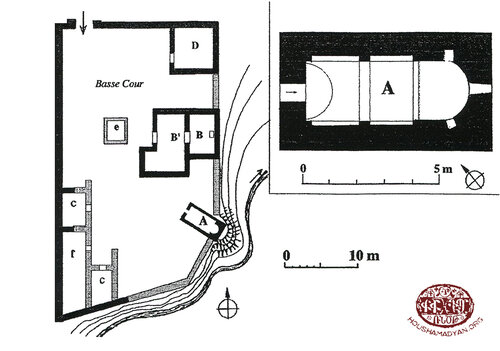

2) The floor plan of Avak Monastery: A) Holy Mother of God Church; B) Saint Thaddeus Church; C) Saint Garabed Church; C1) Sacristy.

(Source: Jean-Michel Thierry de Crussol, Monuments arméniens de Haute-Arménie, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2005).

The monastery’s estate included a bountiful vineyard, a grove of mulberry trees, a large forest, and about 150 plots of arable but fallow fields. The monastery’s parish consisted of more than 10 Armenian-populated villages in Gamakh [23].

One of the monastery’s ancient treasures was the Teghtap Stone. It was a round, concave, sky-blue sapphire, about the size of a small hand, carved with the portraits of a man and a woman. According to legend, this stone was a gift from Constantine the Great, the Roman Emperor, to King Drtad. The two carved figures were said to be the Roman emperor and his wife. The locals believed that the stone had healing powers [24].

Thanks to the Teghtap and other relics it housed, the Avak Monastery was the most popular of the holy sites on Mount Sebouh. Every summer, it would attract large numbers of pilgrims and visitors [25].

The monastery’s custodianship was the hereditary prerogative of the Prokhoronian (Prokhoranian) family, whose members also served as abbots upon taking the monastic vows [26]. The Prokhoronians insisted that they were the progeny of a great house of pagan priests and had the innate right to lead the monastery [27]. They were the custodians not only of the Avak Monastery, but also other monasteries in the area, risking their lives to defend them from regular Kurdish raids, and not allowing the local Kurds to destroy the vast forests of the Mount Sebouh. Their income consisted of what they earned by cultivating the monasteries’ fields, as well as remittances from a few young members of the family who had emigrated to the United States [28].

During the Hamidian Massacres, the abbot of the Avak Monastery, Father Vartan Prokhoronian, who was also the interim prelate of Gamakh, defended the monastery against Kurdish bandits with courage and determination. For this, he was jailed, then exiled to Constantinople, where he remained until his death [29].

The Saint Krikor the Illuminator Monastery (Medz Lousavorich)

The Saint Krikor the Illuminator or Medz Lousavorich (Great Illuminator) Monastery was located on the western flank of Mount Sebouh. According to legend, it was founded in the fifth century at the site of Krikor the Illuminator’s death, near the Manya Cave (hence, it was also called the Resting Illuminator Monastery) [30].

The monastery’s main church, the Saint Krikor the Illuminator, was a structure divided into two sections – the inner sanctum and outer temple [31]. The inner sanctum housed Saint Krikor’s left arm, as well as his cross pendant [32]. Northeast of the Saint Krikor was the Holy All-Savior Church, a small structure with a domed roof [33]. Adjacent to this church was a spring called Pareham, which was famed for its plentiful and delicious water, and which, according to legend, had sprung from the ground as a result of a miracle attributed to Saint Krikor [34]. Beside the spring was the main cave of Manya, and below the monastery was the rock called the Rock of Drtad. According to legend, it marked the site where Drtad, King of Armenians, had been baptized as a Christian [35].

The monastery compound was surrounded by a high, brick wall with a forged-iron gate [36].

The monastery owned arable fields and a large forest. Its parish consisted of five-six villages in Gamakh [37].

Like the Avak Monastery, the Saint Krikor the Illuminator Monastery was under the custodianship of the Prokhoronian family [38].

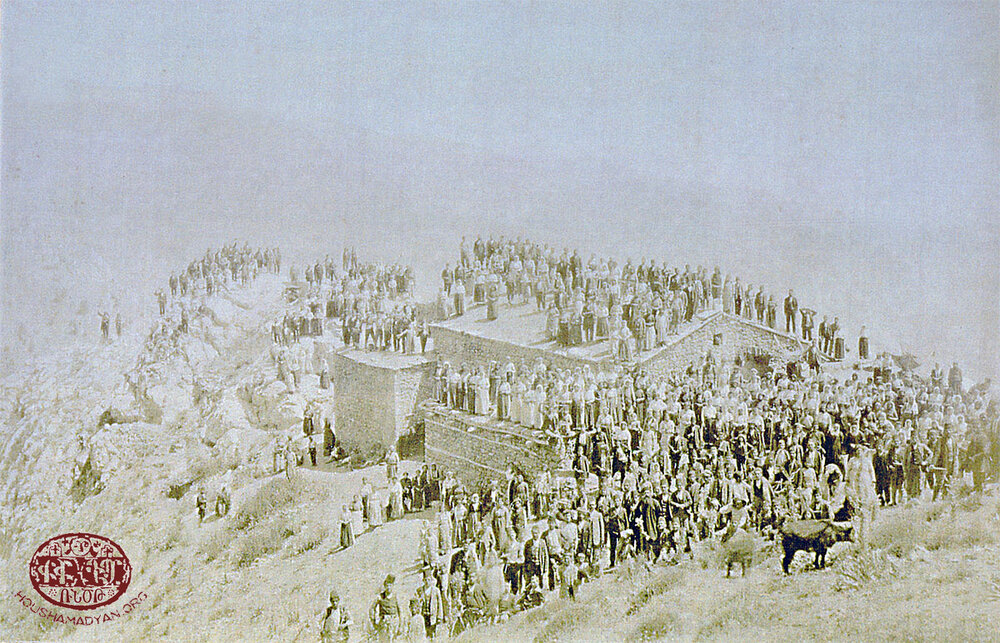

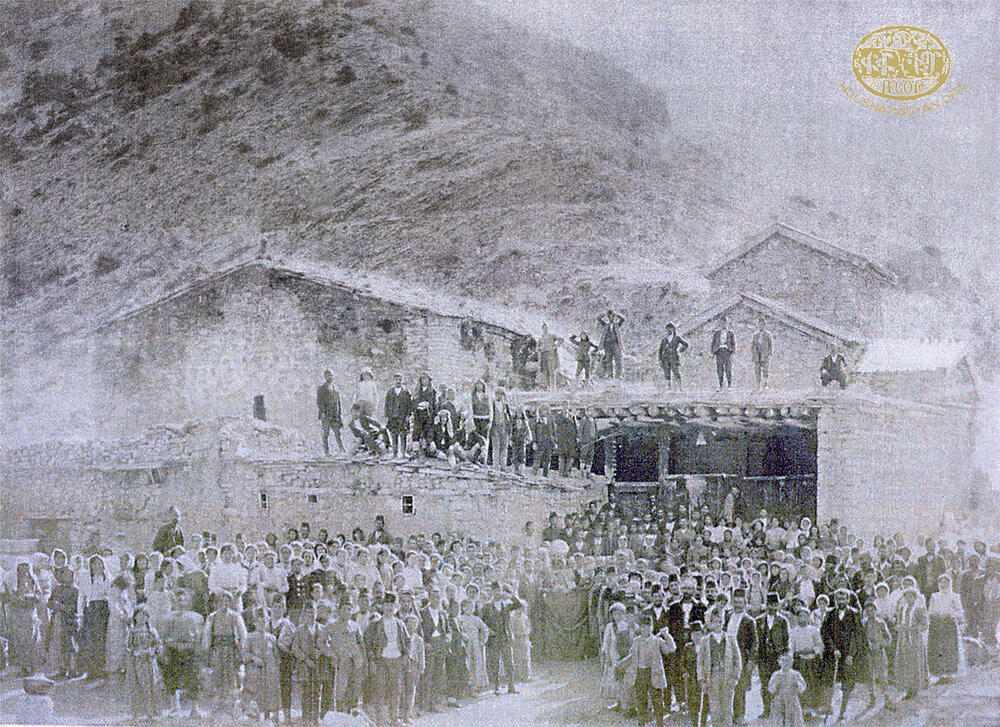

The monastery’s pilgrimage day coincided with the holiday of the internment of Krikor the Illuminator’s remains (Kud Nskharats) (on the third Saturday of the Pentecost). “On the holiday of Kud Nshkharats, large numbers of devout Armenians from Erzindjan and from all over Greater Hayk would make their way up the mountain, in groups, usually on foot. Holding candles, they would head to the high altar, kneel, and pray, some weeping. Some pilgrims would even spend the night in the church, praying constantly and only sleeping intermittently. Infertile women would mix soil from Krikor the Illuminator’s grave with water and drink the mixture, hoping for a miraculous cure,” wrote a pilgrim who participated in these events [39].

The monastery was heavily damaged during the Hamidian massacres. The church was plundered and destroyed, as were the monastery’s other buildings. Father Taniel Hagopian, then Prelate of Erzindjan, visited the monastery in 1901, and found it in a dilapidated state, also mentioning that in order to rebuild the Saint Krikor and Erzindjan’s other monasteries, and to refurbish them to a point where they would be usable and capable of being taken into the care of custodians, the prelacy would need a sum of 250-300 Ottoman pounds [40].

The Holy Savior Monastery of Tortan (Grave of the Nine Saints)

The Holy Savior Monastery of Tortan (also called Holy Cross and Saint Nshan [41]) was located on the western flank of Mount Sebouh, at a distance of about seven hours from Erzindjan, in the historic Armenian village of Tortan [42]. It was also known as the Grave of the Nine Saints, because according to legend, it was the final resting place of King Drtad III the Great, his wife Ashkhen, and his sister Khosrovitoukhd; Saint Krikor the Illuminator; the catholicoses of the Armenian church who were descendants of Saint Krikor – Vrtanes, Housig, and Krikoris (Bishop of Aghvank); as well as two famous ecclesiastic figures from the fourth century, Taniel the Assyrian and Khat [43].

By the eve of the Genocide, only the church building had been left standing from the erstwhile prosperous monastic compound. It served as the parish church for the village of Tortan [44].

The church was divided into an inner sanctum and outer temple. The outer temple, as was the custom, had three altar tables, brick walls, and a ceiling of logs. The entrance to the inner sanctum was underneath the dais of the main altar table of the outer temple. The inner sanctum was entirely built of stone and mortar, with a stone ceiling, and designed in the shape of a cross. It featured a cathedra, with an eight-sided summit. The sanctum had only a single high altar, built underneath the eastern arch. Buried underneath the altar were the relics of King Drtad the Great and Queen Ashkhen. Immediately adjacent to them, below the inner arch, were the tombs of Khosrovitoukhd and Taniel the Assyrian. Below the northern arch was the tomb of Vrtanes, built of stone and with a four-cornered cathedra atop it, its four columns supporting a miter-shaped dome. Right across Vrtanes’ tomb, under the southern arch of the sanctum, was the tomb of Housig [45].

Krikor the Illuminator’s tomb was on the southern side of the western arch. It would be the first tomb seen by pilgrims upon entering the sanctum. The tomb’s architecture was similar to those of Vrtanes’ and Housig’s, except that it was larger. Krikoris’ tomb was also located in the inner sanctum [46].

Khat’s tomb is mentioned as being located in the southern section of the sanctum, inside the side vestry [47].

The Functioning Armenian Monasteries of Erzindjan

The Saint Hagop Mdzpnya Monastery (Gayipos Monastery, Gabos Monastery)

The Saint Hagop Mdzpnya Monastery was located about 20 kilometers west of the city of Erzindjan, on the southeastern flank of Mount Sebouh. According to popular etymology, the monastery was called Gayipos, or more correctly “ga i pos” [there is a ditch], because it was located in a small gorge on the flank of the mountain. According to another theory, the more ancient nickname of the monastery was Gabos, because it was once named after Saint Galibos [48].

Compared to Erzindjan’s other monasteries, Saint Hagop was located at a higher altitude. “There are only two seasons here: the frigid winter and the jovial spring,” noted Sarkis Adamian, who visited the monastery in the mid-1880s [49].

The monastery compound included the church, built of polished stone, with a beautiful and high dome. It also included a small belfry, a narthex, a rectory, as well as a two-story dormitory with several clean rooms reserved for pilgrims [50]. The compound was surrounded by a sturdy and high wall. By the 1880s, it was already showing signs of falling into disrepair [51].

The monastery owned large tracts of arable fields (the equivalent of 40 parcels) and pastures [52]. However, due to its distance from the city, the monastery was regularly raided and plundered by Kurdish bandits, as a result of which its custodians often abandoned it and decamped [53]. In the mid-1880s, the custodian was Khachadour Agha, brother of Father Vartan, the interim prelate of the Gamakh Diocese [54]. By 1901, custodianship of the monastery had been entrusted to a Kurdish family, “in order to save it and its lands from being lost irretrievably” [55].

As a result of its distance from the city and lack of safety, the monastery was visited by few pilgrims. Most of the monastery’s visitors were the same Armenians who had made pilgrimages to the other holy sites of Mount Sebouh, the Medz Lousavorich and Avak monasteries [56]

The Shoghakat Holy Virgin Monastery

The Shoghakat Holy Virgin Monastery was located about 10 kilometers west of the city of Erzindjan, at the base of Mount Sebouh. According to legend, it was founded by Saint Thaddeus the Apostle (in the first century). It was later renovated on the orders of Catholicos Nerses the Great (in the fourth century), as well as in the 1680s, during the term of Avedik Yevtogatsi [57].

The monastic compound consisted of the church building, not particularly large, and with an arched roof; the single-story rectory; and a two-story guest house, with the second floor reserved for pilgrims, and the first floor used as a barn, stable, granary, etc. [58]. The monastery was surrounded by a wall, which was, however, low and in disrepair [59]. Adjacent to the compound were its large orchard and grove, as well as pastures [60].

Located at some distance from Kurdish-populated villages, the Holy Virgin was relatively safe from raids and attacks. The residents of the nearby Turkish-populated village of Shokhd had always maintained peaceful relations with the monastery [61].

In the later years of the 19th century, custodianship of the monastery was entrusted to lay Armenians. Historical records mention the names of two of these custodians – Nshan Effendi Sdepanian and his son, Sarkis Effendi Sdepanian [62].

With its temperate climate, clean and salubrious air, sapid (though not plentiful) water, and other advantages, the monastery was one of the favorite pilgrimage and vacation destinations for the Armenians of Erzindjan. The summer homes of some of the city’s wealthiest Armenians were also located in its environs [63].

Charcharanats (Dadasgi; Bearer of Sufferings) Saint Illuminator (The Little Illuminator Monastery)

On the eve of the Genocide, the Charcharanats Saint Illuminator was the largest and oldest functioning monastery in Erzindjan. It was located about 25 kilometers southeast of the city, at the base of the Merdjana (Doudjig) Mountains. The Merdjan River flowed beside the monastery, and due to this, it was also known as the Merdjana Monastery [64].

The monastery’s cathedral (its main church) was described as simple and elegant, built of stone and mortar in the classical architectural style. Aside from the cathedral, the monastic compound also included a small chapel called The Prison of the Saint Illuminator [65]. The relics preserved in the monastery included Krikor the Illuminator’s gold- and silver-plated right hand, as well as seven small spikes, which, according to Akatankeghos, were used to torture the first patriarch of the Armenian Church. According to legend, the monastery was built at the very site where Saint Krikor was tortured. The monastery’s treasures also included relics from other saints, sacred vessels, parchment manuscripts, etc. To defend itself against raids by Kurdish bands, these treasures were kept in a special cellar, and were taken out only on special occasions, such as holidays, and displayed to worshippers in special ceremonies [66].

The monastery’s parish included the villages of Meghoutsig, Gharatoush, Akrag, and Djandjige (the latter already Kurdish-populated by the end of the 19th century). The monastery received tithes in the form of fruit from the villagers [67].

The monastery compound also included living quarters for monks, a kitchen, a refectory, a granary, and some agricultural buildings, including a barn, a stable, a hayloft, an apiary, etc. The monastery owned large tracts of arable fields, pastures, gardens, and vineyards. The compound was protected by a wall. The two northern corners of the wall had observation posts, from which Kurdish raiders could be spotted from a long distance, allowing the monastery to prepare for their raids [68].

The monastery’s salubrious air and delicious water, as well as breathtaking views it offered, made it one of the most popular summer pilgrimage destinations for the Armenians of Erzindjan. Even several local Turkish officials and notables spent their summer holidays in the monastery [69].

Between 1870 and 1895, the monastery’s abbot was Father Ghevont Der-Boghosian. Being a sagacious, energetic, and erudite leader, he was able to improve the monastery’s financial situation and restore it to relative prosperity. In the mid-1880s, The Charcharanats Saint Krikor the Illuminator was the only monastery in Erzindjan with a large, productive, and self-sufficient economy [70]. Father Ghevont, using his connections as protection, managed the monastery independently, rebuffing all attempts by community organizations to place it under the management of a board of trustees [71].

The Charcharanats Saint Krikor the Illuminator was in this prosperous state on the eve of the Hamidian massacres. However, in October 1895, the monastery was attacked by a Kurdish band. Father Ghevont defended his domain heroically, and died in the process. The Kurds then proceeded to plunder the monastery [72].

In later years, the monastery continued to be administered by members of Father Ghevont’s large family. However, these custodians were able to organize the cultivation of only a portion of the monastery’s expanses of arable fields [73].

The Dirashen Saint Nerses Monastery

The Dirashen Saint Nerses Monastery was located 10 kilometers south of the city of Erzindjan, on a steep cliff in the foothills of Mount Mntsour [74]. According to legend, the monastery was founded by the Armenian King Diran II (reigned from 338 to 350), hence the name “Dirashen” or “Diranashen” [built by Diran] [75]. The monastery was consecrated as the Saint Nerses Monastery in 1275, when, thanks to a vision, Saint Nerses’ relics were rediscovered and brought to be preserved there [76].

Dirashen was one of Erzindjan’s largest and most famous functioning monasteries [77]. The monastic compound consisted of the “outer” church, with its large and small domes, and the relatively small, but handsome main cathedral, both built of polished gray stone. Inside, to the right of the main door, was as vestry, where the church’s utensils and clerical vestments were kept. Below the cathedral was the cellar, where the valuable sacred vessels and ancient treasures were stored (a golden chalice, silver-plated and gold-plated boxes of relics, silver crosses, etc.) The walls of the church were decorated with oil-painted icons, famous among which was the large painting of Saint Nerses, placed in the center of the altar table [78].

On the southern side of the cathedral was a door that allowed entry into the tomb of Saint Nerses – a small and dark room, with the remains of the Saint interred in the wall. An account of the relics’ discovery was affixed to the saint’s tombstone [79].

From ancient times, the monastery was famed for the outer church’s “zarmanakordz” [“magnificently crafted”] door, carved with religious motifs, figures, inscriptions, and uncial letters that were difficult to decipher [80].

The monastery complex also included a guest house, living quarters for pilgrims, a barn, and a cattle shed. The compound was surrounded by high walls [81]. In the mid-1880s, the monastery’s assets included 36 plots of land, eight sheep, seven goats, five cows, and three calves [82]. Adjacent to the monastery was a meadow, ringed with mulberry trees, willows, and poplars; as well as a vegetable garden, another garden, and a large fruit orchard.

In view of its proximity to the city of Erzindjan, Saint Nerses was under the jurisdiction of the Erzindjan Diocese, and the subject of special care by the city’s population. It attracted countless pilgrims and visitors [83]. In the 1880s, a boarding school also operated on the monastery grounds.

Like the other monasteries of Erzindjan, Saint Nerses was entrusted to the care of custodians. In the 1880s, Father Vartan, a native of Terchan, held this position. He had fled his birthplace and moved to the monastery to escape the persecution of a Turkish landowner called Kut [84].

Saint Nigoghos of Ptaridj (Saint Nigoghayos)

The Saint Nigoghos (Saint Nigoghayos) Monastery was located about 25 kilometers southeast of the city of Erzindjan, at the base of the Keshish and Sare-ghaya mountains, near the village of Ptaridj [85].

On the eve of the Genocide, the monastery compound consisted of the domed cathedral, a large narthex, a rectory, living quarters for pilgrims, and various buildings necessary for the monastery’s economy (shed, barn, hayloft, etc.). The compound was surrounded by a high and sturdy wall [86].

In the 1880s, the monastery’s custodian was Father Kapriel Der-Maroukian, from the village of Meghousig. He managed the monastery’s field, orchards, and large vineyard [87].

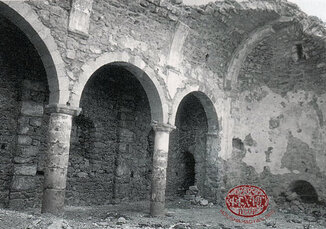

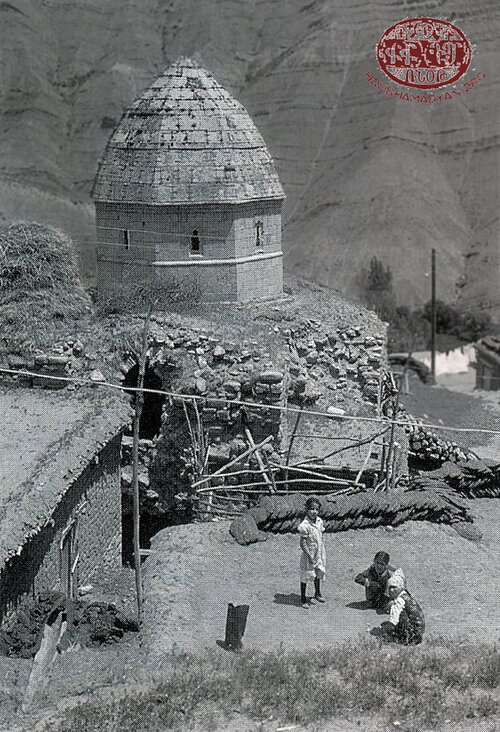

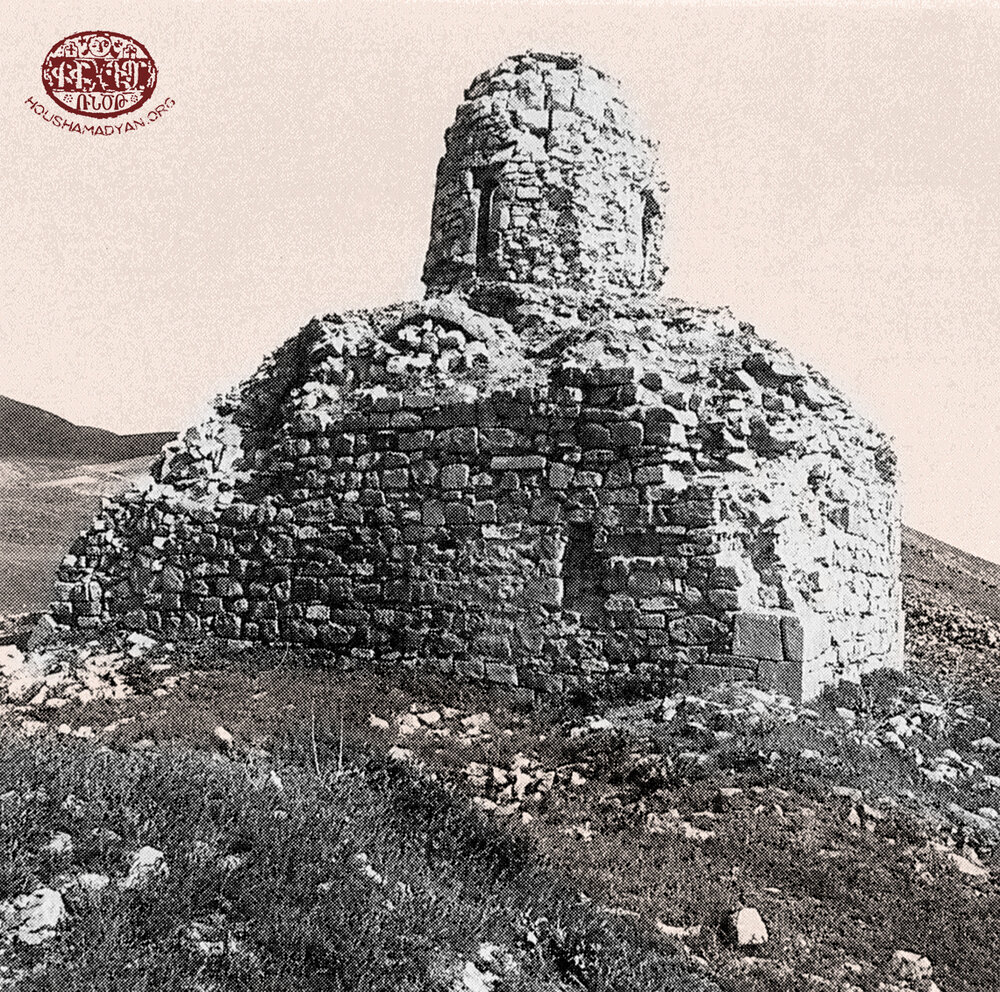

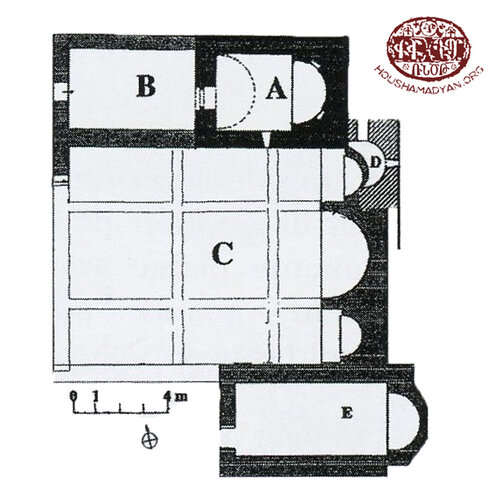

1) Floor plan of the St. Nigoghos (Nigoghayos) Monastery – Ptaridj: A) Church; B) Narthex; C) Saint Nicolas Church; D) Chapel; E) Chapel.

2) Ruins of the St. Nigoghos (Nigoghayos) Monastery – Ptaridj.

(Source: Jean-Michel Thierry de Crussol, Monuments arméniens de Haute-Arménie, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2005).

Records mention Apraham Agha, from Ptaridj, as the custodian of the monastery in the 1900s. He is said to have been an “intrepid personality, who overcame many challenges to protect the monastery from the plundering and pillage of the Turks and Kurds” [88].

The parish of the monastery consisted of the villages of Ptaridj, Gharakilise, Aghdjekend, Khntsoreg, and Shkhli [89].

With its position in the foothills of the mountains and the beautiful scenery it offered, the monastery was a beloved holiday/pilgrimage destination for the local population. One description of these pilgrimages reads: “In the vast mulberry orchards, cooled by the large fronds, the pilgrims scatter, sitting on cushions or bedding. Some stone the mulberry trees, others climb them and shake their branches, yet others frantically collect the fallen mulberries (mostly the women, girls, and boys). Some – the men – drink from bottles of arak. They place their bottles in a large spread on the green field, beside the trays of roasted lamb. Some play backgammon, some chess. Others hunt, their shots ringing intermittently through the forest” [90].

The Saint Kevork Monastery of Yergan

The Saint Kevork Monastery of Yergan was located approximately 20 kilometers southeast of the city of Erzindjan, near the Armenian-populated villages of Yergan and Geoltsnik, on the flank of the Doujig (Merdjan) Mountains [91].

The monastery had two adjacent churches. One was the Saint Kevork [92], described as unimpressive, dark, and damp; and the other was the Holy Virgin, built of stone, small, and sturdy. Both churches were in a dilapidated state [93].

The monastery compound included living quarters for monks and pilgrims (15-20 rooms) and buildings necessary for the monastery’s economy (store, barns, etc.), and was surrounded by a wall [94]. A sacred spring flowed on the monastery grounds. The water was drunk by pilgrims, who believed it had miraculous healing powers. The monastery owned about 50 parcels of arable fields, as well as a large fruit orchard [95].

The custodianship of the monastery was entrusted to the copper workers of Erzindjan, who organized fundraisers among themselves to care for the monastery. They also visited the compound regularly [96].

The Saint Giragos Monastery

The Saint Giragos [97] Monastery was located at the base of Mount Mntsour, at a distance of an hour and a half (eight kilometers) southeast of the city of Erzindjan, near a Kurdish-populated village [98]. The monastery’s geographic position was described as lofty, offering beautiful views of the Erzindjan Valley below it. The monastery compound, with its noble and captivating appearance, was visible from all angles [99].

On the eve of the Genocide, the monastery consisted of the main church, adjacent to which were the living quarters consisting of 8-10 rooms and two terraces (ayvans) reserved for pilgrims [100]. Several illuminated parchment manuscripts, as well as the relics of Saint Giragos, were kept at the church [101].

The monastery compound was not walled, and lacked gardens, fruit orchards, and arable fields. Across a gorge was the mountain called Saint Yeghia, covered in greenery, where the monastery’s flocks grazed. In the gorge flowed a sacred spring, renowned for its frigid, clear, and plentiful waters [102].

Abutting the monastery was a cave called the Madourig [Small Chapel], which, according to legend, had been Saint Giragos’ cave dwelling [103].

Thanks to its location, its salubrious air and water, and its proximity to the city, during the summer months, especially around Vardavar (Feast of Transfiguration), the monastery became one of the area’s main destinations for pilgrims and visitors. Most of the monastery’s income was earned from these visitors [104].

The custodianship of the monastery was entrusted to a board of trustees created by Armenian commercial painters from the city of Erzindjan, with a remit to “care for and make improvements to the monastery” [105].

The Miyavor Saint Garabed Monastery

The Miyavor Saint Garabed Monastery was located southwest of the city of Erzindjan, at a distance of about two-three hours (about 12 kilometers), at the base of the Aghtagh peak of the Soupnkor (Sourp Krikor [Saint Krikor]) Mountains [106]. The monastery’s structures were described as “outdated” and “dilapidated.” The cathedral, the main church of the compound, though high-domed and spacious, was in half-ruins. The wall around the compound was described as “sturdy.” By the 1880s, the monastery had already lost some of its lands, and was considered to be impoverished. It only owned about 12 parcels of unirrigated fields, and a fruit orchard adjacent to the compound, which lay abandoned [107].

Nevertheless, the views of the Erzindjan Valley that the monastery offered, and its clean air and water, attracted relatively large numbers of pilgrims from the city and surrounding villages during the summer months [108].

The custodianship of the monastery was the hereditary prerogative of the Torosian family, natives of the neighboring Armenian village of Garmri [109].

The Saint Boghos-Bedros Monastery (Chakhermanou Monastery)

The Saint Boghos-Bedros (Peter-Paul) or Chakhermanou [Warder of Evil] Monastery was located at a distance of approximately two hours (10-12 kilometers) northeast of the city of Erzindjan, on the flank of Mount Keshish. It offered clean, salubrious air; delicious and frigid waters; and splendid views [110].

The monastery’s church was built of stone, and was a small structure. It was surrounded by living quarters and buildings necessary for the monastery’s economy [111].

At the start of the 19th century, the monastery was under the custodianship of the Dadian family of Constantinople, whose members had renovated the compound and had maintained its buildings for some time [112].

By the 1870s, the monastery had fallen into disrepair, and was administered by a Turkish custodian, who had turned it into a cattle barn. In the early 1880s, Bishop Hmayag Timaksian appointed a lay Armenian custodian to administer the monastery, and also created a board of trustees for it, whose members were chosen from the Armenian residents of the village of Pzvan. He was also able to recover some of the monastery’s lands that had been appropriated by the Turkish and Kurdish residents of neighboring villages (the monastery owned a vineyard and about 50 parcels of arable land) [113].

- [1] A. Kh. Safrasdian, “Gonstantnoubolsi Hayots Badriarkarani goghmits Tourkyayi Artaratadoutyan yev Tavanankneri Minisdroutyan Nergayatsvadz Yegeghetsineri yev Vankeri Tsoutsagnern our Takrirnere (1912-1913)” [“Lists of and Reports on Armenian Churches and Monasteries Presented by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate to the Turkish Ministry of Justice and Religious Denominations (1912-1913)”], Etchmiadzin, Bashdonagan Amsakir Hayrabedagan Atoro Sourp Etchmiadzni [Etchmiadzin. The Official Monthly Digest of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin], 1965, A, January, pages 45-47. An independent review of the information provided by this report was performed by French-Armenian researcher Raymond Haroutyun Kévorkian (see Raymond H. Kévorkian, Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la Veille du Génocide [The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide], ARHIS, Paris, 1992, pages 59 and 453-455.)

- [2] Archbishop Drtad Balian, Hay Vanorayk [Monasteries of Armenia], Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, 2008, pages 168-180.

- [3] H. Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere [The Monasteries of Upper Hayk], Vienna, Mekhitarine Order Press, 1951, pages 53-113.

- [4] Buzantyon [Byzantium], December 20, 1897 (January 1, 1898), n. 351; Giragos S. Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner Oughevoroutyan [Mixed Correspondence of Travels], Constantinople, Sareyan Press, 1887, pages 22-26. The same monasteries are listed as functioning in the 1878 survey of the Erzindjan Diocese (Charents Museum Archives, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, case 42, sheet 7). Nine standing monasteries in Erzindjan (albeit some “in disrepair and dilapidated”) were also listed by Sarkis Amadian (Arevelyan Mamoul, Smyrna, February 1887, page 49). For another list of the monasteries of the Erzindjan Diocese, see 1904 Entartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1904 Complete Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1904, page 369. However, it must be noted that this latter list is inaccurate, as it omits the Saint Boghos-Bedros Monastery and includes the Holly Hairabed (Holy Abbot) Monastery of Til, which was already in ruins by 1904 and was no longer functioning.

- [5] K. Surmenian, Yerznga [Erzindjan], Cairo, Sahag-Mesrob Press, 1947, page 86.

- [6] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1887, page 49-50.

- [7] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 102. The author attributes the healing powers of the water to the increased circulation of blood throughout the body.

- [8] Arkam, “Yerzngayi S. Lousavorich Vankn yev ir Temere” [“The Saint Illuminator Monastery of Erzindjan and its Parishes”], Arevelyan Mamoul, December 1899, pages 24 and 1024.

- [9] Surmenian, Yerznga, pages 91 and 99.

- [10] Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, page 24.

- [11] For the full text of the contract, see Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 54-55.

- [12] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1887, pages 50-51.

- [13] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 102.

- [14] Ibid., page 104.

- [15] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1887, page 51.

- [16] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 104.

- [17] “Hayasdanyats Yegeghetsin Dadjgasdanoum” [The Armenian Church in Ottoman Turkey], Ararad, February 1896, page 88.

- [18] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 3; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 181.

- [19] Ibid.

- [20] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 104.

- [21] Ibid., page 88; Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 364.

- [22] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 88.

- [23] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 182.

- [24] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 86. According to another theory, the Teghtap Stone was a gift to Krikor the Illuminator from Pope Silvester I (Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 182).

- [25] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 181.

- [26] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” Ararad, 1901, numbers 7-8, page 364.

- [27] Bishop Yervant Perdhadjian, “Taraghanyats Kavare (Hayreni Housher)” [“The Province of Taraghan (Memories of the Fatherland)”], Sion, Year A, July-August 1927, n. 7-8, page 213

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 364; Bishop Yervant Perdahdjian, “Taranaghyats Kavare,” page 213.

- [30] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 185.

- [31] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 363. For a detailed, architectural description of the church, see Jean-Michel Thierry, Sebouh Leran Houshartsannere (Hnakidagan Ousoumnasiroutyunner)” [The Monuments of Mount Sebouh: Anthropoligical Studies], Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, 1989, 36 (D-Z), pages 80-81.

- [32] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, pages 33-34.

- [33] Jean-Michel Thierry, “Sebouh Leran Houshartsannere,” page 81.

- [34] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 88.

- [35] Bishop Yervant (Perdahdjian), “Taranaghyats Kavare,” page 213.

- [36] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 34.

- [37] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 185.

- [38] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 91.

- [39] Bishop Yervant (Perdahdjian), “Taranaghyats Kavare,” page 213.

- [40] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 364.

- [41] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 31.

- [42] On the eve of the Genocide, Tortan had 46 Armenian households and an Armenian population of 430 (Kévorkian and Paboudjian, Les Arméniens…, page 456).

- [43] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 362. According to Bishop Yervant Perdahdjian, the church also housed relics of Arisdages, Nerses the Great, Sahag Bartev (Isaac of Armenia), and Karnig the Hermit. However, Perdahdjian also stated that according to historical sources, only the remains of Krikor the Illuminator, Vrtanes, and Housig were interred at Tortan. The resting places of Arisdages and Nerses the Great were in the town of Til, in the ruins of the Choukhdag Hayrabedats (Twin Abbots) Monastery. Sahag Bartev’s resting place was in Ashdishad, in Daron. Krikoris was thought to have been buried at the Saint Krikoris Monastery of Amaras, and Khat was buried at the church of the village of Hanksdoun in Keghi (for more on Khat, see Houshamadyan’s article Keghi – Churches and Monasteries; and Bishop Yervant Perdahdjian, “Taranaghyats Kavare,” page 212).

- [44] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 186.

- [45] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 362.

- [46] Ibid.

- [47] Ibid.

- [48] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, pages 69-70.

- [49] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1888, page 98.

- [50] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 97.

- [51] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1888, page 99.

- [52] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 177.

- [53] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 98.

- [54] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1888, page 100.

- [55] Father Taniel Hagopian, “Sebouh Leran Srpavayrere,” page 364.

- [56] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1888, page 100; Surmenian, Yerznga, page 98.

- [57] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 173; Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 99.

- [58] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 98.

- [59] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 173.

- [60] Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, page 24.

- [61] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 97.

- [62] Arevelyan Mamoul, September 1889, page 175.

- [63] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 97.

- [64] Surmenian, Yerznga, pages 94-95; Arevelyan Mamoul, August 1887, pages 380-381.

- [65] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 171.

- [66] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 95.

- [67] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 102.

- [68] Ibid.; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 171.

- [69] Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, page 25.

- [70] Arevelyan Mamoul, August 1887, page 383.

- [71] Arkam, “Yerzngayi S. Lousavorich Vankn yev ir Temere,” page 1047.

- [72] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 95.

- [73] Arkam, “Yerzngayi S. Lousavorich Vankn yev ir Temere,” page 1047.

- [74] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 92.

- [75] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 49.

- [76] Ibid., page 50.

- [77] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 174.

- [78] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 92.

- [79] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 50.

- [80] Ibid., page 51.

- [81] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 106.

- [82] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, pages 51 and 54.

- [83] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 93.

- [84] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 53.

- [85] Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 96.

- [86] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 99.

- [87] Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, page 22; Arevelyan Mamoul, August 1887, page 380; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 170.

- [88] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 100.

- [89] Arevelyan Mamoul, August 1887, page 380.

- [90] Arshavir, “Menasadanneri Shourche. S. Nigoghos Vank” [“The Environs of Hermitages. The Saint Nigoghos Monastery”], Masis, Constantinople, August 5, 1906, n. 21, page 334.

- [91] Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, age 25; Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 56.

- [92] K. Surmenian listed this site as a chapel (Surmenian, Yerznga, page 91).

- [93] Arevelyan Mamoul, September 1887, pages 437-438.

- [94] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 91.

- [95] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 180.

- [96] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 91; Arevelyan Mamoul, September 1887, page 438.

- [97] The full name of the monastery was “Saint Giragos and his Mother Saint Yughida,” so it is also mentioned in records as the Saint Giragos-Yughida Monastery (Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 82).

- [98] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 168; Surmenian, Yerznga, page 93; Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, pages 82-83.

- [99] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 93.

- [100] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 56; Surmenian, Yerznga, page 94.

- [101] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 94.

- [102] Ibid.

- [103] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 168.

- [104] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 94.

- [105] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1888, page 57; Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, page 24.

- [106] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1887, page 52; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 172.

- [107] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1887, page 52; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 173.

- [108] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 94.

- [109] Ibid., page 98.

- [110] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 170; Vosgian, Partsr Hayki Vankere, page 100.

- [111] Surmenian, Yerznga, page 99.

- [112] Ghazandjian, Kharn Namagner, pages 22-23.

- [113] Arevelyan Mamoul, February 1887, page 53; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, page 170.