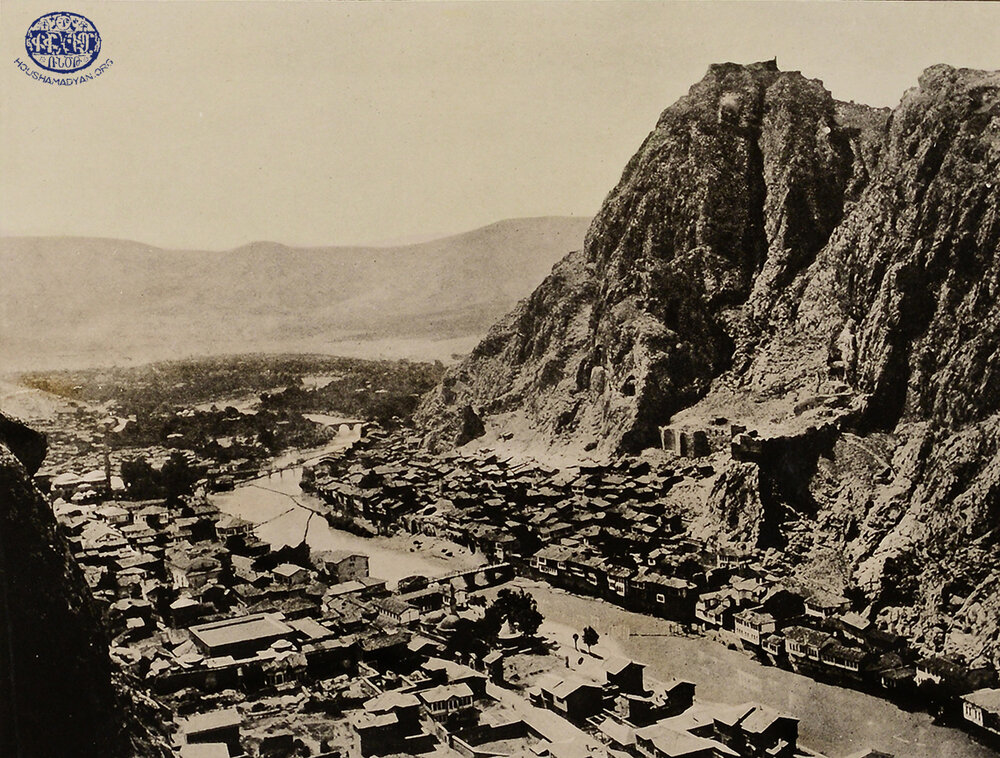

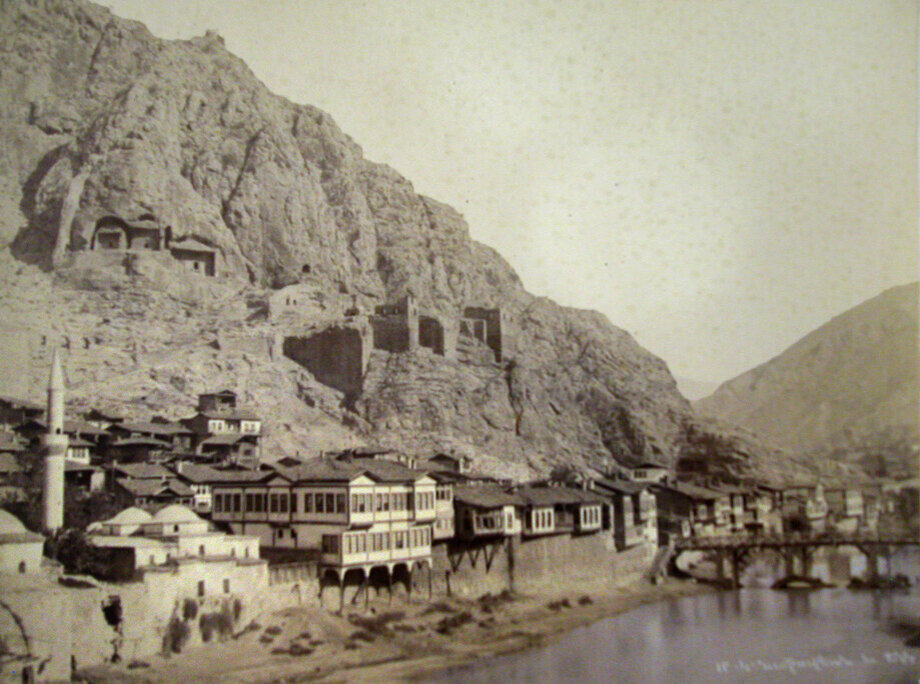

Amasya – Trades and Commerce

Author: Lory Tashjian, 01/02/2022 (Last modified: 01/02/2022) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Armenians of Amasya were known for their affluent lifestyle. At least, that is the impression conveyed by Kapriel Simonian’s expansive work, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo [Memory Book of Pontic Amasya]. In his book, Simonian asserts that each household in the city owned at least a home and an orchard. Household wealth commonly ranged between 200 and 1,000 Ottoman pounds, which was a significant fortune at the time. There were also about forty households in Amasya whose assets – both estates and funds – were thought to range between 1,000 and 7,000 Ottoman pounds.[1]

There were few destitute or needy Armenian families in Amasya. Employment opportunities were plentiful, and those who wished to work were never left idle. Many Armenian peasants from the province of Sebastia/Sivas came to Amasya to work as porters. After a year of diligent labor, they would save enough to send a few medjides back to their families. Many Armenians who had moved to Amasya in pursuit of better economic opportunities had permanently settled down in the city and had become locals. These migrants came from places like Arapgir, Agn, Gesaria (Kayseri), and Gurun.[2]

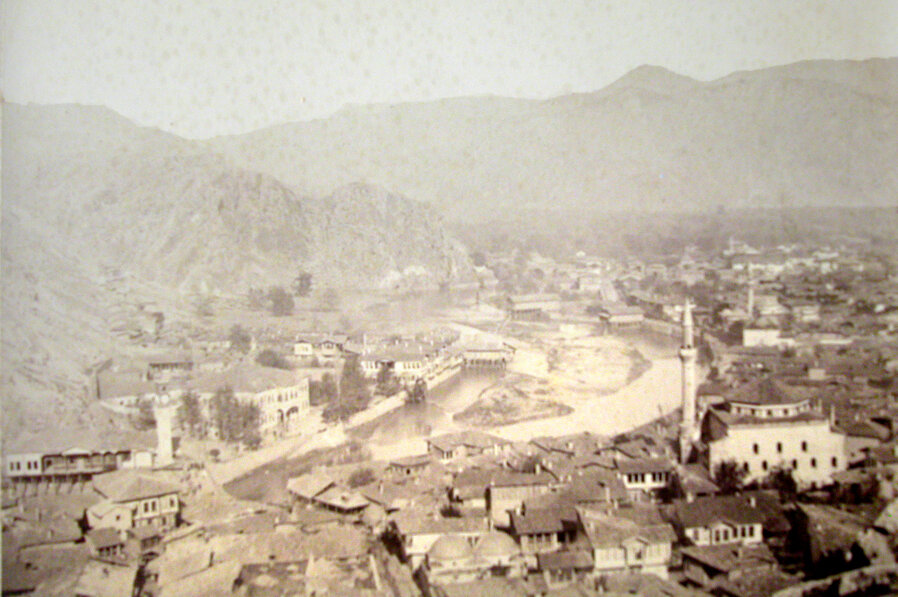

Most of the Armenians of Amasya were craftsmen. Few were engaged in agriculture. The arable fields around the city were owned mostly by Turks. Armenians were known as skilled artisans. Many crafts were passed down from one generation to the next. The most numerous workshops in the city were those operated by tailors, blacksmiths, carpenters, cobblers, fabric weavers, and tinsmiths. As Amasya was rich in water, the city was also home to many flour mills, as well as silk factories. Alongside these crafts, other important sectors of the city’s economy included grape farming and various other types of agriculture.

The people of Amasya actively traded with neighboring cities and villages. They exported weaved fabric, leather, wool, flour, grain, dried okra, grapes, apples, wine, djehri (a yellow, plant-based dye), etc.

The grape harvest. Judging from the individuals’ attire, the photograph may have been taken in the 1920s or 1930s. As such, we cannot be certain that it was taken in Amasya. It appeared in a memory book of Amasya, which indicates that the individuals in the photograph were Armenians from the city (Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice).

This article explores the occupations commonly practiced by the Armenians of Amasya in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Where possible, we have provided the names of notable practitioners of each occupation. Our main source of information was Kapriel Simonian’s book, which focuses heavily on the crafts practiced by the city’s Armenians.[3] The statistics provided throughout the article concern the period preceding the Armenian Genocide.

Bakers and Confectioners

Amasya was famous for its baked goods. The city’s bakers and confectioners were renowned throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Early each morning, bakers would prepare the ring-shaped biscuits that were locally known as simit. To make it, they would dip the dough in boiling water and then keep it exposed to steam for some time. They would then sprinkle the dough with roasted sesame seeds and bake it in the oven.

Other local favorites included cheoregs made with butter, oil, and walnuts; the cheoregs known as nokhoudlou and djevizli; and the biscuits served on Christmas Eve.

Five Armenian master bakers were active in Amasya, specializing in various pastries. Locally, a baker/confectioner was known as a cheoregdji. One of Amasya’s Armenian cheoregdjis was Armenag Moroukian. He had attended the Jesuit School, but had preferred to follow in his father’s footsteps and had become a baker. When the Armenian Genocide began, Armenag and one other Armenian baker from the city were exempted from the deportation order, as their work was considered essential for the local Muslim population.[4]

The bakeries of Amasya also produced high-quality bread rolls and loaves. Local favorites included the pide, an oval-shaped, thin, and long loaf; as well as the thin and round rolls baked on Muslim holidays. Approximately eight Armenian bakeries operated in Amasya. Among the well-known bakers were Ekmekdji Nazar Nazaretian, Ishkhan Yeghian, and another baker known by the moniker Godjagdji.[5]

Two Turkish confectioners (shekerdjis) sold various types of sweets in Amasya. The most renowned confectioners were Armenian, and the most celebrated among them were Haroutyun Karadjian and ShekerdjiGhaysertsi (Gesaratsi, the demonym for Gesaria/Kayseri) Dikran.[6]

The helva of Amasya was also famous. It was made with tahini oil, flour, and sugar. Five or six different types of helva were made. One type of local helva was made in the shape of a rooster’s spur and was sprinkled with roasted sesame seeds. Another variety, the Saint Sarkis helva, was made with walnuts and served in large pieces. Ohan Yeghiazarian was renowned for his delicious helva. There were also two Turkish helvadjis in Amasya. At home, Armenian women would also prepare a type of helva that looked like a finely spun bundle of hay. This was called tel-tel [stringy] helva. It was difficult to make, and it was served to special guests on winter nights.[7]

Ironsmiths, Tinsmiths, Coppersmiths, and Related Trades

The number of Armenian ironsmiths (demirdjis or chilingirs) in Amasya, including apprentices, reached 150. They primarily made blades for ploughs, axes, hoes, weapons, oars, shovels, etc.[8] According to figures from 1890, a total of 30 ironsmith’s workshops operated in Amasya, all owned by Armenians.[9]

There were 11 Armenian tinsmiths (tenekedjis) in Amasya. They produced various items made of tin. The most senior among them was Kapriel Djamdjian, who specialized in tin samovars. According to figures from 1890, there were five tinsmith’s workshops in Amasya, all of them owned by Armenians.[10]

The nearby cities of Tokat and Merzifon/Marzvan boasted a larger number of coppersmiths. In Amasya, there were a total of eight coppersmith’s workshops. Among the well-known local coppersmiths were the Mavian brothers and Kazandji Hovhannes. The latter was an expert in European-style stills for the distillation of spirits.[11]

Amasya was home to two Armenian master bell makers (changhdjis). They would melt copper and other metals and cast small and large bells. They would also make candelabras, censers, and similar items out of yellow brass.[12]

Five Armenian knife-makers (buchakdjis) were active in Amasya. In addition to knives, they also made penknives, shears, shuttles for weaving looms, etc. Among the well-known knife-makers were the Panosian brothers.[13]

There were two Armenian and one Caucasian-Tatar stove makers (sobadjis) in Amasya. They used sheets of iron to make stoves and associated piping. The two Armenian stove makers were Nshan Tabakian and Armenag Samourkashian.[14]

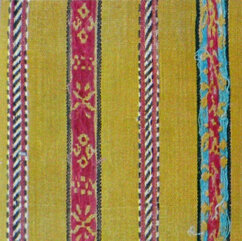

Manisa Weavers (donloukhdjis)

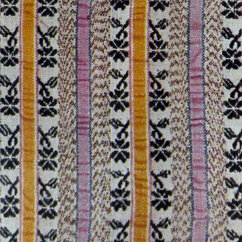

More than ten Armenians in Amasya owned workshops that produced woven manisa and other textiles. These workshops were generally built in the courtyards of large homes, and they were staffed exclusively by Armenians. The textile produced by these workshops was sold wholesale. In addition to these workshops, many families had looms in their own homes. Men and women both made use of these looms. All who worked in this industry were Armenian.

Manisa weaving ensured employment for workers in many other sectors of Amasya’s economy, including dyers, craftsmen who built and repaired various parts of looms, ironers, etc. Both men and women worked in the manisa factories, which, at some point, hired more than 1,000 locals.

The largest manisa weaving factories in the city were owned by the Ipranosian and Enfiyedjian brothers. Those who owned smaller workshops included the Terzibashian family, Hovhannes Begian, Hagop Kazandjian, and the Bahchegoulian family. Toros Deovletian and Haroutyun Izmirian also owned workshops, but both emigrated to the United States before 1915.

Most of the woven manisa was sold within the province of Amasya. In his book, Kapriel Simonian writes that this profession was dealt a heavy blow when the Ipranosian brothers began importing cheap fabric and embroideries from England.[15]

Sock Makers (chorabdjis)

It was customary in Amasya to wear socks knitted at home. Until 1915, the city had a store that sold socks, owned by a Turk. Kasbar Ipegian and Kevork Jamgochian owned sock factories. A total of 10-15 machines were used in these factories to produce Western-style socks.[16]

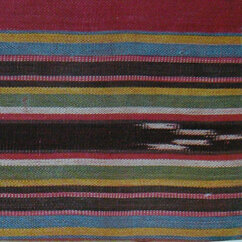

Dyers

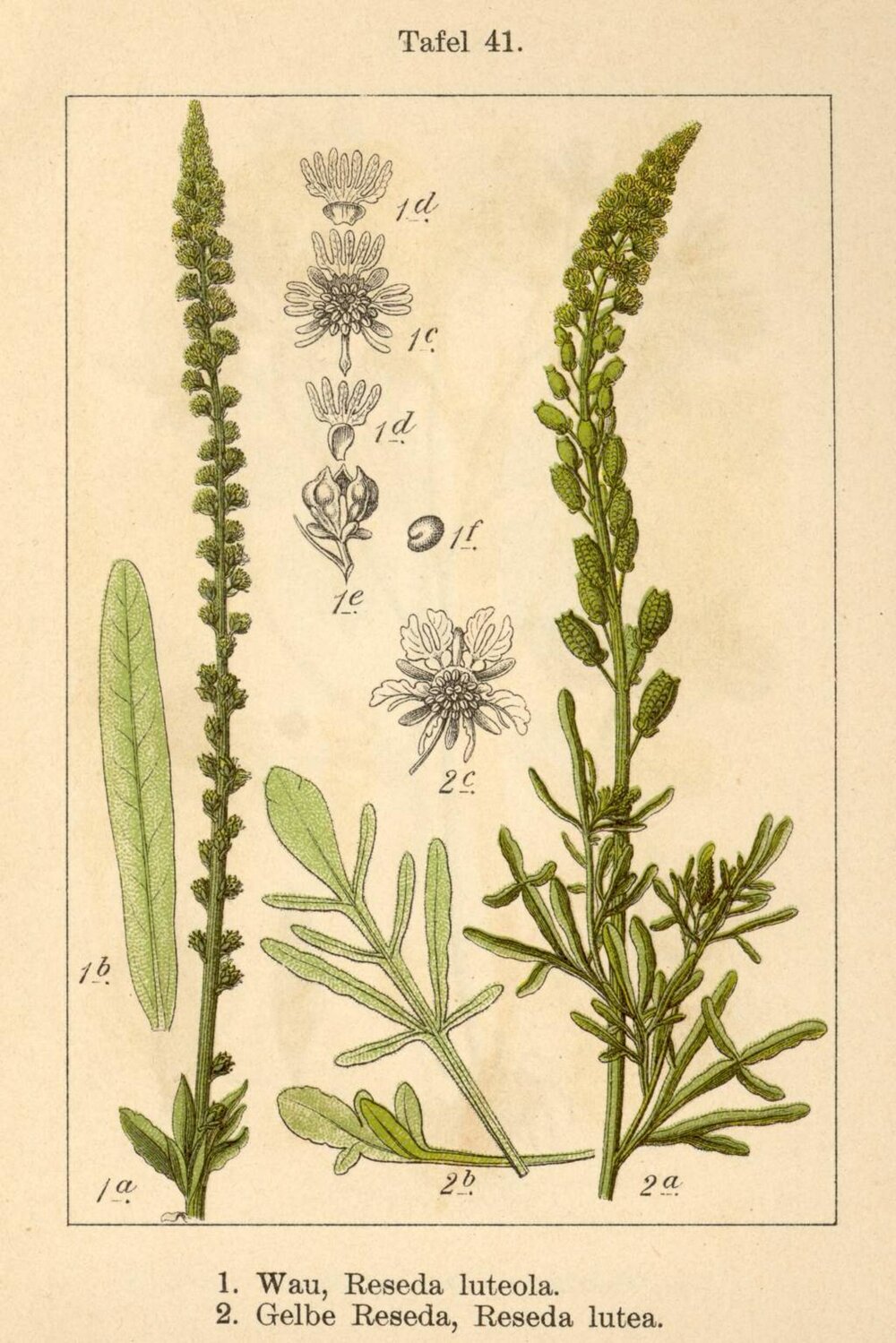

Approximately 15 Armenian dyers (boyadjis) were active in Amasya. They would dye weaved textile and yarn in various colors. They used different roots and plants to make their dyes, of which the most popular was the yellow dye of the fruit of the bush known as djehri (dyer’s weed, reseda luteola). Some of this dye was exported to Europe. Many grew this plant in their own fields. But in later years, cheaper chemical dyes began appearing in Amasya, imported from Europe (mostly from Germany). This put an end to the use of djehri. Abandoned groves of these bushes could be found in many parts of the city for many years into the future.[17]

Djehri (dyer’s weed, reseda luteola) (Source: Johann Georg Sturm / Jacob Sturm, Deutschlands Flora in Abbildungen, 1796; http://www.biolib.de/sturm/flora/high/Sturm06041.html).

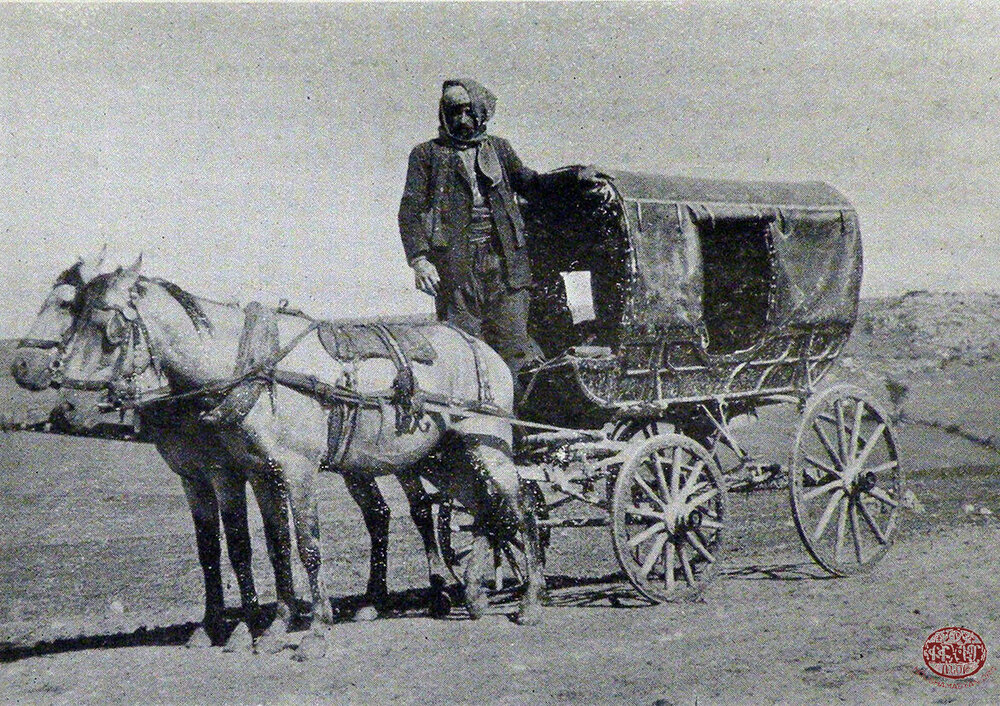

Charioteers (arabadjis) and… The First Automobile in Amasya

There were about 50 Armenian charioteers in the city, in addition to about ten Arnavoud (Albanian) and a few Caucasian-Muslim (Tatar) charioteers.

Amasya was connected to Tokat and Samson by a chariot road that was kept in good repair. Four-wheeled chariots, drawn by two or three horses, transported various wares from Amasya to Samson, and from there to Kharpert, Diyarbekir, Kayseri, and other cities in the Anatolian heartland. Among the well-known local charioteers were Kevork Danadjian, Hadji Hagop Ourzandjian, Kevork Shahsuvarian, Hovhannes Tyulegian, and Hagopdjan Panosian.

An arabadji was a craftsman who build chariots. Of those active in the city, five were Armenians and two were Caucasian Muslims. The Armenian arabadjis built springed and covered chariots.

Notably, an automobile association was founded in Amasya in 1910. Among its members was Armenag Samourkashian, whose brothers Dikran and Apisoghom had emigrated to the United States. They had sent a car to Armenag from America – the first car to ever appear in the city. Armenag also imported bicycles from Europe.[18]

Saddle Makers

One Circassian and two Armenian saddle makers kept workshops in the market of Amasya. They made a type of Circassian horse saddle called egher and silver horse tack; as well as saddles called osmanlu, tack for pack horses, belts for humans, etc. Among the masters of this craft were Mardiros and Hovhannes Adzigian. They were known for decorating their horse saddles and chariots with silver trimmings called savatlou.[19]

Loom Comb Makers (darakdjis)

Prior to the arrival of European metal loom combs in Amasya, Hadji Hovhannes Simonian made loom combs in his workshop in the city, where he employed the master craftsmen Ohan Darakdjian, Garabed Zorigian, and others. Hadji Hovhannes was known as a darakdji. He was a skilled master who repaired the shuttles of weaving looms with the wooden tools he had crafted. He also made a variety of solid and sturdy loom combs, as well as special combs made of local reed used by the local villagers. Hadji Hovhannes would also import much harder reeds from Adana to make higher-quality loom combs.

Among Hadji Hovhannes’ permanent clients were the two best-known producers of silk in Amasya, the Ipedjian and Ipranosian families. Hadji Hovhannes also often received orders from nearby Merzifon, and even from Constantinople.

In the early 20th century, merchants began importing European metal combs into Amasya. As a result, Hadji Hovhannes and his son, Mihran, were forced to close their workshop and instead became merchants.[20]

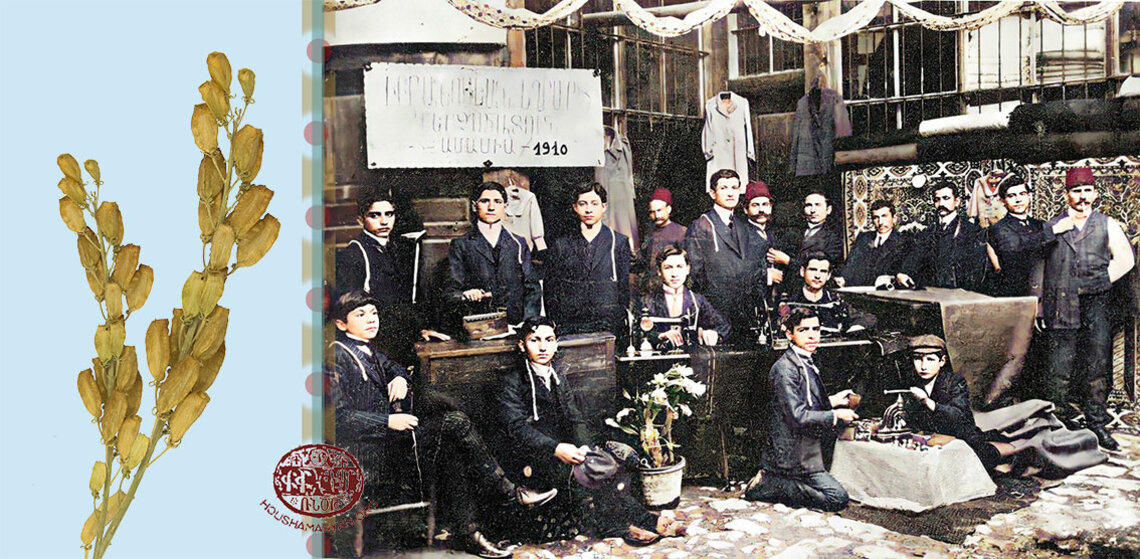

Tailors and Embroiderers

There were more than ten Armenian tailors in Amasya who owned their own workshops. They sewed bespoke clothing for their customers. None of them specialized in women’s clothing. There were about ten Armenian women in the city who owned sewing machines at home and sewed clothing for acquaintances and customers. According to figures from 1890, there were a total of 20 tailor’s workshops in Amasya, of which 15 were Armenian-owned and five were Greek-owned.[21]

After the reinstatement of the Ottoman Constitution in 1908, Armenian women attended sewing lessons in a workshop in Amasya that was run by Father Kachouni.[22]

Alongside these traditional tailors, Amasya was also home to seamsters who specialized in sewing traditional local attire. These tailors were called abadjis, as their main product was the aba (cloak). Four Armenian and one Greek abadjis were active in Amasya. The Ipranosian brothers’ factory also produced abas. The factory’s manager was Hovhannes Tarpinian, who later opened his own tailor’s workshop.[23]

Embroiderers (nakhshudjis) were usually women and young girls. They worked at home. Among the well-known local embroiderers was Mrs. Kayane Elbegian, who was assisted by her two daughters.[24]

Barbers

It was customary for the men of Amasya to be groomed at least once a week. There were eight Armenian barbers (berbers) in the city. The most senior among them was Vahan Dingilian, who had moved to the area from Constantinople and had later returned to Amasya. The barbers of Amasya also practiced primitive dentistry.[25]

Butchers

Well-known local butchers (ghassabs) included Merdinian; Yesayi Yezegian and his son, Yezeg; Kerovpe Kebabdjian and his sons; Arisdages Manasian; Parsegh Parseghian; the Tavitian brothers; and others. Sources also mention two Turkish butchers, one of whom was named Timarkhanedji. He later became notorious for beheading Armenians with his butcher’s knife during the Armenian Genocide.[26]

Machinists and Casters

All machinists in the city were Armenian. Among the master machinists were Krikor Melkonian (who later emigrated to America), the brothers Hagop and Zakar Khachigian, the Boghosian brothers, Haroutyun Ejdarian, Roupen Avakian, Hovhannes Deyirmendjian, Kapriel Kirishdjian, Mihran Ferhadian, and others.[27]

Most of the casters (deokmedjis) who made the various components of the machines used in Amasya’s factories were Armenian. Well-known among them were Nazaret Nazarian and Hampartsoum Tabakian.[28]

Cobblers (ghondouradjis) and Drekh Makers (charoukhdjis)

The master cobblers in Amasya who made all types of European-style men’s and women’s shoes (ghondouradjis) were Armenian. A Greek cobbler also worked in the city. Among these shoemakers, the best-known were Hadjidjanian and sons, Haroutyun Apetian, and the Keolian and Bakhtiyarian brothers.[29]

Charoukhdjis practiced a different branch of cobblery. They made charoukhs (drekhs), which were worn mostly by villagers. The drekh was made from the dried hide of cattle. About ten drekh makers were active in the city, including Toros Saadetian.[30]

According to figures from 1890, there were a total of 50 cobbler’s workshops in Amasya, of which 35 were owned by Armenians and 15 were owned by Greeks.[31]

Carpenters

There were six Armenian carpenters (marangeoz) in Amasya, among whom Hovhannes and Krikor Djamdjian were the best-known. They made delicate and elegant items of furniture. Another well-known local carpenter was Krikor Djurian, who worked with solid logs of cedarwood that he transported down the river from the forests near Tokat. He built boxes with this wood that were used to export shelled walnuts and misget apples. The same type of wood was used to make coffins and furniture. According to figures from 1890, there were a total of ten carpenter’s workshops in Amasya, all owned by Armenians.[32]

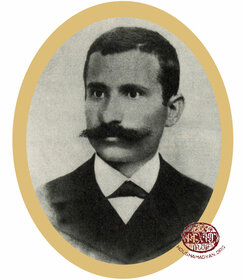

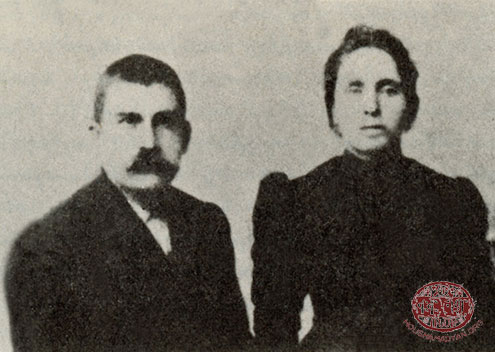

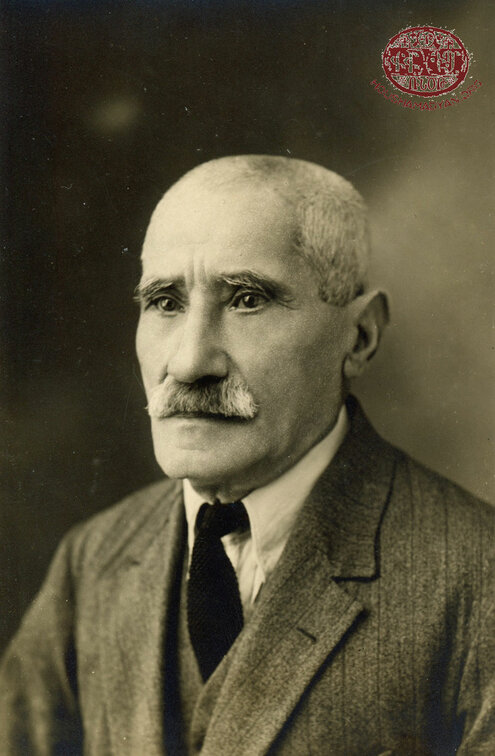

Hamaprtsoum Zakarian and his wife, Lucia Zakarian. Hampartsoum was born in Amasya in 1880 and attended the local Ipranosian technical school, where he studied machinery. He was killed in 1915 (Source: Kapriel H. Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo [Memory Book of Pontic Amasya], Saint Lazarus Island (Venice), 1966).

Jewelers

Amasya was home to six jewelry workshops that belonged to Armenians. Oundjian Ghouyoumdji Yeghia was one of the famed local jewelers (ghouyoumdjis) who crafted delicate ornaments and betrothal rings of gold and silver. Hovhannes Yeremian was also well-known for his skill in engraving gold, silver, and aluminum.[33]

Silkworm Farmers

Among the most senior silkworm farmers (tokhoumdjis) in Amasya were Dimoteos Balukdjian, Hovhannes Pepeyan, Akif Effendi, and Apetnakov Shamlian. Among the well-known younger silkworm farmers were Nshan Evranian and Aram Tarpinian. According to figures from 1907, a total of 17 silkworm farmers practiced their trade in Amasya. Collectively, they produced approximately 25,000 boxes of silkworm eggs. Some of these eggs were exported as far afield as Tbilisi.

Amasya was also home to a silkworm farming school under the direction of Boghos Vartabedian, who had moved to the area from Constantinople.[34]

Ropemakers

There were six Armenian master ropemakers (ourghandjis) active in Amasya. Rope was made in the following way: a machine would be fastened to the ground right at the workshop entrance. A bundle of combed hemp would be tied around the master’s torso, and the other end would be tied to the two screws of the machine. The master would walk backwards, which would cause the machine’s screws and wheel to turn. The master would continuously roll the hemp with his fingers while walking backwards, braiding the strings into strong threads. By the time he reached the back of the workshop, a rope with a length of 30 meters would be made. This type of rope was called ghunnab, and it was used to tie bags and for other needs. There was a type of ghunnab made with three threads of hemp instead of two, called sidjim. Thicker ropes could also be made by combining multiple ghunnabs. Ghunnabs were also used to make reins for pack animals, cinches to secure packaging, etc.[35]

Ghoutoudjis

A ghoutoudji was an artisan who made paper and cardboard boxes. Among the local masters of this craft was Mgrdich Chakurian, a former teacher, who was better known as Reverend Mgrdich. The delicate boxes that he made for silkworm eggs were in great demand. There was also another master ghoutoudji in the city, Hagop Kirishdjian. The latter had built a machine that could make perforated paper boxes, in which silk moths could be kept and lay eggs.[36]

Glaziers

The first person to import glass for windows and lamps into Amasya was Kapriel Djamdjian. His son was also a glazier (djamdji) and had mastered his craft. He was also a practicing tinsmith.[37]

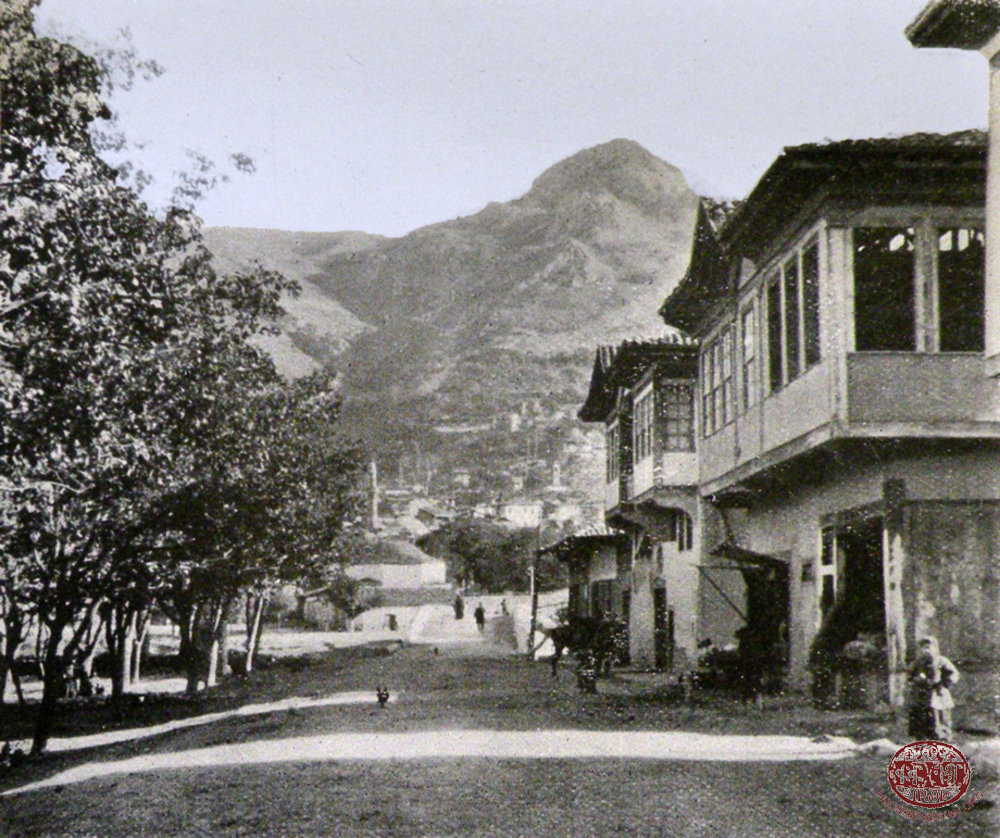

Amasya, early 1930s. A sewing school still operating in the small Armenian community that had survived the Genocide. The school was directed by Miss Yaghlian. Standing, first from the left, is Verjin Niksarlian. The others in the photograph are unidentified (Source: Lerna Yanık collection, Istanbul).

Silk Weavers

There were four Armenian masters in Amasya who practiced this trade in its traditional form. Silk weavers (ipekdjis) were craftsmen who extracted silk from the cocoon of the silkworm. The term ipekdji was also used to describe the owners of modern silk factories.

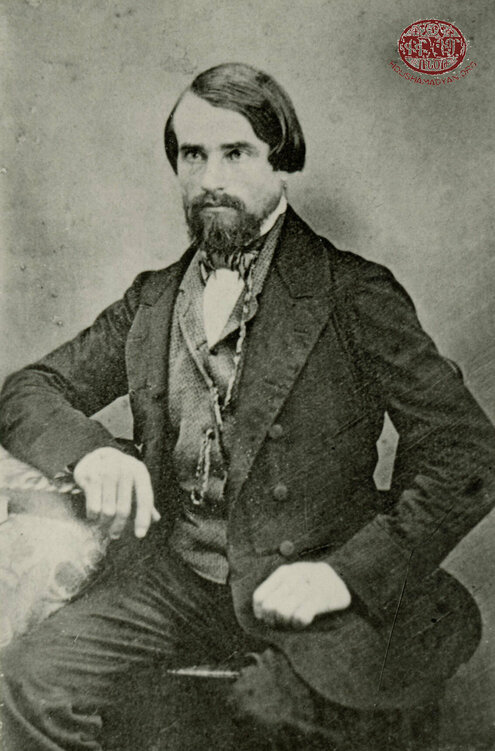

The first such factory in Amasya was founded in 1852 by Georg Krug, a Swiss-German. He was sent to Amasya by Carl Mez, a well-known silk manufacturer from Freiburg (Germany). The factory that Krug managed boasted about 50 looms and employed about 100 female workers. Presumably, the factory was shuttered in the late 19th century.

Later, two modern silk factories were opened in the city, one of which was owned by Marouke Ipekdjian. The other was owned by the Ipranosian brothers. The Ipranosians already owned a manisa cotton factory, and their silk factory soon became the biggest in the city. The factory was managed by Minas Ipekdjian, Marouke Ipekdjian’s son. In 1907, this factory had 55 dezgyahs (looms).[38]

Goat Hair Weavers (moutafs)

These craftsmen used rudimentary tools to weave goat hair and make sturdy bags and sacks. Among the Armenians who practiced this trade were Hadji Khachig Marmarian and the Tavdjian family.[39

Stones Cutters (dashdjis)

In Amasya, the master craftsmen who built dry-stone walls without bricks were usually Greek, but there were also four or five Armenian craftsmen engaged in this occupation. Moreover, about 20 Armenian master masons (bennes) were active in the city, alongside Greek and Turkish masons.[40]

Tanners (khaghakhorts, dabakhs)

Tannery had been practiced in Amasya since ancient times. Most tanners in the city were Armenians. They made a type of colorful leather called sakhtiar out of goat and sheep hide. The leather made of cattle hide was used to make soles for shoes. The Diradourian brothers (Hagop, Giragos, and Dikran) owned a modern leather factory. It was located in the family’s estate near the Bey Bagh orchards of the city. The Diradourian brothers’ business was so successful that they opened an office in Constantinople and branches in Merzifon, Zile, and Sivas. In addition to producing high-quality leather, they also imported and retailed various items and supplies needed by the city’s cobblers and shoemakers.[41]

Millers (deyirmendjis)

Amasya was rich in streams and rivers. The Iris (Yeşilırmak) River flowed through the city. From ancient times, small and large water-powered mills had operated in Amasya. Many flour factories were built on the banks of the Yeşilırmak River, two of which were founded by German and French engineers. The remaining 50 or so mills were built by self-taught Armenian millers. According to figures from 1890, there were 20 modern mills in the city, alongside many smaller mills. Many Armenians were employed by these mills. The flour they produced was used for local consumption and was also exported to Samson.[42]

The small Germany community that had settled down in Amasya played an important role in the proliferation of mills and the development of milling skills among the city’s Armenians. To wit, two watermills were built in the mid-19th century in Amasya by German families. One of these was powered by the Iris River, and the other by the Ziare River. These ethnic Germans had migrated to Amasya from both Germany and Switzerland, mainly with the intention of engaging in sericulture. But in later years, they had expanded into other sectors of the local economy, including the operating of mills. These modern machines were a novelty for the local population. The watermill on the bank of the Iris River began operating around 1858. It was the brainchild of Georg August Krug, a Swiss. The Armenian workers he employed learned the skills and secrets of the trade, which were a complete mystery to their compatriots. In later years, they built their own mills in Amasya. In 1898, an article that appeared in the Puzantion [Byzantium] newspaper of Constantinople stated that more than a hundred mills were operational on the banks of the Iris and Khodor rivers, and that the owners of these mills had either previously worked in Krug’s mill or had been apprentices of the latter.[43]

Another miller active in Amasya was Johann Kallenbach. He had moved to the area from Germany and had later married a local Armenian woman, Amali Ansourian.[44]

In later years, the engineering of local mills, as well their modernization, owed much to Krikor Melkonian (1856-1939) and Hagop Khachigian. Krikor Melkonian emigrated to the United States in 1904. Among other Armenian millers, historical sources mention Nigsarlian Hadji Agha, Krikor Kayutian, Garabed Papazian, the Khachigian brothers, Nshan Yaghlian, and the Hovnanian brothers. The mill known as Chalan Fabrica was owned by a local Turk, but its master miller was Ohan Tutundjian, an Armenian.[45]

Restaurant Owners/Cooks (ashdjis)

There were four or five restaurants in Amasya owned by Armenians. The most well-known among them was Ashdji Artin Agha (Haroutyun Karadjian). There were also seven kebab stalls owned by Armenians in the upper and lowers markets in the city.[46]

Combers (halladj)

These artisans combed wool and cotton using primitive tools. There were three Armenians in Amasya engaged in this occupation.[47]

Chickpea Roasters (leblebidjis)

Four Armenians and one Turk in the city were engaged in this occupation. They would peel chickpeas, roast them, and sell them. Roasted chickpeas were called cherez, and they were consumed mostly during the Christmas holidays.[48]

Currency Exchangers (sarrafs)

There were four currency exchangers working in the market of Amasya – Bennekhachigian, Parsegh, Dikran, and Garabed Tellalian. In their shops, these businessmen were engaged in the trade of jewelry, accessories, and antiques more than the trade of currencies.[49]

Tile Makers (kiremidjis)

An Armenian by the name of Mekenian had founded a factory in Amasya that produced European tiles for roofs, bricks for walls, and four-sided baked tiles for the ground floors of buildings. Three or four Armenians owned factories in Amasya that produced local varieties of tiles and bricks.[50]

Photographers

The first photographer in Amasya was an Armenian by the surname of Naldjian. He had learned his craft in Europe. During the massacres and looting of 1895, Naldjian’s home and studio were looted. After these events, he no longer practiced his trade. Those who followed in his footsteps included Ghazaros Kaiyan, Tornig Terzibashian, and Hrant Gemidjian (Photo Hrant).[51]

Dolabdjis

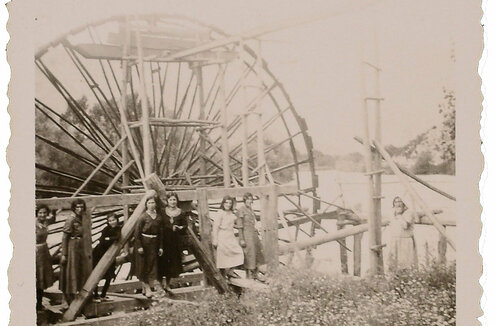

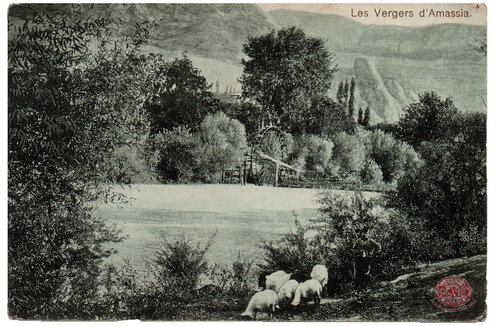

Dolabdjis were craftsmen who made and maintained the norias that were installed on the riverbanks to secure the city’s water supply. These water wheels (dolabs in Turkish) ensured a supply of water to the vineyards, orchards, and gardens of Amasya during the dry summer season. In the fall, the wheels were dismantled, and then re-installed in the spring. A few Armenians had mastered this craft, but most of its practitioners were Turks.[52]

1) Amasya. Armenian women photographed in front of a noria (Source: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice).

2) Amasya. In the background, a noria is visible on the bank of the Iris (Yeşilırmak) River. This post office was printed by Ardashes Kerkeselian, from Amasya (Source: Lerna Yanık collection, Istanbul).

Potters

There were four potter’s (cheomlekdji) workshops in Amasya, three owned by Armenians and one by a Greek.[53]

Other Occupations

- Pewterers (kalaydjis): four Armenians.

- Scarf makers (yazmadjis): two Armenians, Meremkoulian and Yazmadjian.

- Maker of shoe molds: Haroutyun Keoleyan.

- Farrier/shoer: one Armenian.

- Makers of handles/grips for shovels, hoes, and other tools (sapdjis): two Armenians.

- Limeburners (kuredjdjis or alchidjis): two Armenians.[54]

Commerce

Alongside craftsmen, both small and large traders (tudjars) were active in the market of Amasya. They were mostly engaged in manifatura, or the trade of local textiles. In hundreds of shops in the Amasya market, they sold attire for both city dwellers and villagers, as well as a variety of fabrics and embroideries. According to figures from 1890, a total of 300 manifatura stalls were active in the city, of which 10 were owned by Greeks, and the rest owned by Armenians.[55]

Among the local retailers of wool, silk, and cotton items were Yesayi, Sarkis, Hovhannes and Hagop Nigoghosian; the Bahdjegulian brothers; the Bekdemirian brothers; Hagop Sarafian; the Ipranosian brothers, who owned four stores; as well as the retail section of the Ipranosian brothers’ factory. As for merchants who sold local attire to the villagers, they included Mgrdich Tinponian, the Dingilian brothers, Krikor Kurkkeselian, M. Djrukian, Kevork Benlian, Shahinian, Djakdjakian, Aroudjian, Adzigian, Zorig Zorigian, Piligian, and others.[56]

The largest commercial establishment in Amasya belonged to the Ipranosian brothers. Others who owned shops included the Mardigian brothers, Eftikis, and Hadji Istil. They would import colorful wool scarves/belts from Gurun, silk embroideries from Diyarbekir, and bath towels from Merzifon and the village of Sim Hadji.

Most of the owners of shops that sold produce and grain to the local population were Armenian. As for wholesale flour merchants, they included Hadji Garabed Chekemian, Mgrdich and Mihran Simonian, Haroutyun Shishmayan, Garabed Papazian, Nigsarlian, Nigoghosian, Levon Deokmedjian, Hayrabed Mouradian, Krikor Boyadjian, Dikran Chalkayudjian, Nshan Benneyan, the Tabakian brothers, etc.

Garabed Papazian exported a type of local apple called misget. Dikran Tellalian, Haroutyun Piranian, Garabed Papazian, Yaghlian, Kevork Benneyan, Garabed Ourghandjian, and others exported okra, opium poppies, and tiftik (a type of wool). Alongside them, many Greek and Turkish merchants also conducted trade in the city.[57]

The shops in Amasya that sold novelties, school supplies, metal items, machines, kerosene lamps, cups, and other sundry items were also almost exclusively owned by Armenians. The best-known among them were the Mardigian brothers, who also owned an establishment in Samson and an office in Constantinople. Others included Ghougas Salian, Khntirian, the Fenerdjian brothers, Bahchegulian, Chebishian, Imirzeyan, Shahsuvarian, Shirinian, and the Armazanian brothers.[58]

- [1] Kapriel H. Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo [Memory Book of Pontic Amasya], St. Lazarus Island of Venice, 1966, p. 628.

- [2] Ibid.

- [3] Ibid., pp. 628-641.

- [4] Ibid., pp. 636-637.

- [5] Ibid., p. 633.

- [6] Ibid., p. 636.

- [7] Ibid., p. 634.

- [8] Ibid., p. 639.

- [9] Loumen, “Deghegakragan – Amasya” [“Geography – Amasya”], Arax Illustrated Review, December 1890, year 3, book B, Saint Petersburg, p. 19.

- [10] Ibid.; Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 633.

- [11] Ibid., p. 633.

- [12] Ibid., p. 636.

- [13] Ibid., p. 638.

- [14] Ibid., pp. 639-670.

- [15] Loumen, “Deghegakragan – Amasya,” p. 18; Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 640.

- [16] Ibid., p. 637.

- [17] Ibid., p. 638.

- [18] Ibid., p. 632.

- [19] Ibid., p. 638.

- [20] Ibid., p. 639.

- [21] Loumen, “Deghegakragan – Amasya,” p. 18; Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 633.

- [22] Ibid.

- [23] Ibid., p. 632.

- [24] Ibid., p. 636.

- [25] Ibid., p. 638.

- [26] Ibid., p. 635.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] Ibid., p. 639.

- [29] Ibid., p. 635.

- [30] Ibid., p. 636.

- [31] Loumen, “Deghegakragan – Amasya,” p. 19.

- [32] Ibid.; Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, p. 635.

- [33] Ibid.

- [34] Ibid., pp. 634, 645-646.

- [35] Ibid., p. 636.

- [36] Ibid., p. 635.

- [37] Ibid.

- [38] Ibid., pp. 609-610, 634; “Arevdouri gyanku kavarneroun mech” [“Commercial life in the provinces”], Puragn Weekly, year 25, number 42, October 1907, Constantinople, pp. 1546-1548.

- [39] Ibid., p.636.

- [40] Ibid., pp. 638-639.

- [41] Ibid., pp. 516, 639.

- [42] Ibid., p. 36; Loumen, “Deghegakragan – Amasya,” pp. 17-19.

- [43] Ibid., pp. 493-494; L. B., “Kermank i Pokr Asia” [“Germans in Asia Minor”], Puzantion, 24 November 1898, year 3, number 639, Constantinople; Iris, “Amasya,” Sourhantag, 17-18 September 1899, number 166-167, Constantinople.

- [44] Jochen Mangelson, Ophelias lange Reise nach Berlin, Donat Verlag, 2001, Bremen.

- [45] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, pp. 36, 493-494, 639; Iris, “Amasya,” Sourhantag.

- [46] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, pp. 40, 632.

- [47] Ibid., p. 634.

- [48] Ibid.

- [49] Ibid. p. 638.

- [50] Ibid., p. 640.

- [51] Ibid., pp. 640-641.

- [52] Ibid., p. 639.

- [53] Ibid., p. 637.

- [54] Ibid., pp. 633-634, 636, 638, 640.

- [55] Ibid., p. 633; Loumen, “Deghegakragan – Amasya,” pp. 17-19.

- [56] Simonian, Houshamadyan Bondagan Amasyo, pp. 633-634.

- [57] Ibid., p. 634.

- [58] Ibid.