Ayntab – Photographers

Author: Mihran Minassian, 27/03/20 (Last modified 27/03/20) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

Overview

In the Ottoman Empire, Armenian photographers were pioneers in their field. They practiced their art in all corners of the country, from the famous Abdullah(ian)s and Pascal Sebah of Constantinople, to those working in the provinces: the Dildilians (Sivas/Sepasdia, Merzifon/Marzvan, Samsun/Samson, and Kastamonu/Kastemonu), the Soursourians (Harput/Kharpert), Garabed Solakian (Konya), Krikor M. Msrlian (Aleppo), Patriarch Yesayi Garabedian and Garabed Krikorian (Jerusalem), Garabed Lekegian (Cairo and Constantinople), and many others. In fact, so many Ottoman photographers were of Armenian descent that in many areas, the occupation was seen as the preserve of Armenians. Based on approximate calculations, more than 500 Armenian master photographers were active at one point or another across the Ottoman Empire, in addition to vendors of photographic equipment, retouching experts, printers and sellers of postcards, etc. After the Armenian Genocide, many of these individuals survived and continued to practice their crafts across the world, from the Middle East to various European cities, and even in the distant corners of Africa and America, where they remained unmatched in their skills.

A General Overview of Armenian Photography in Ayntab

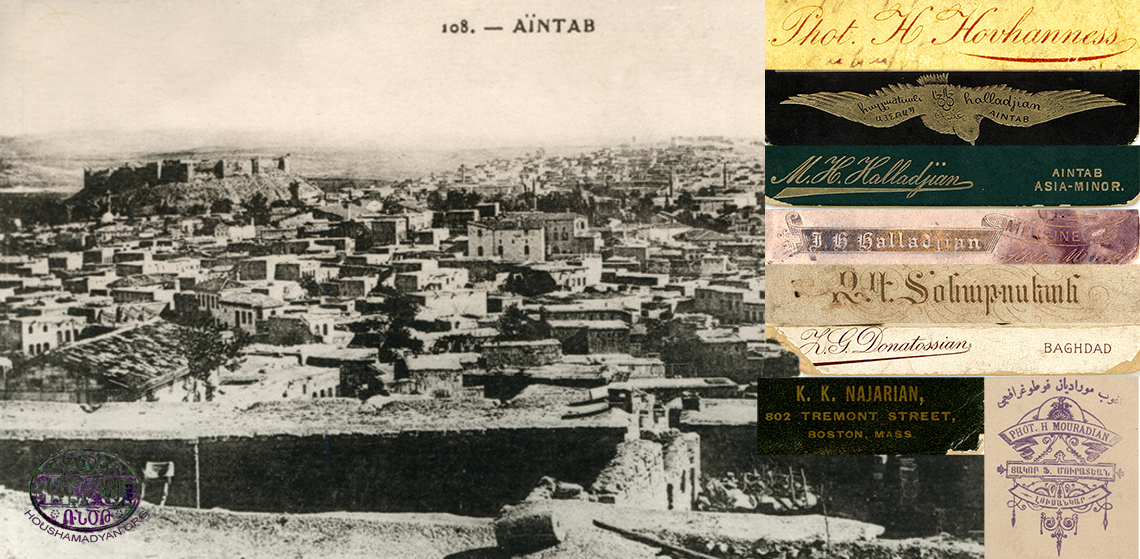

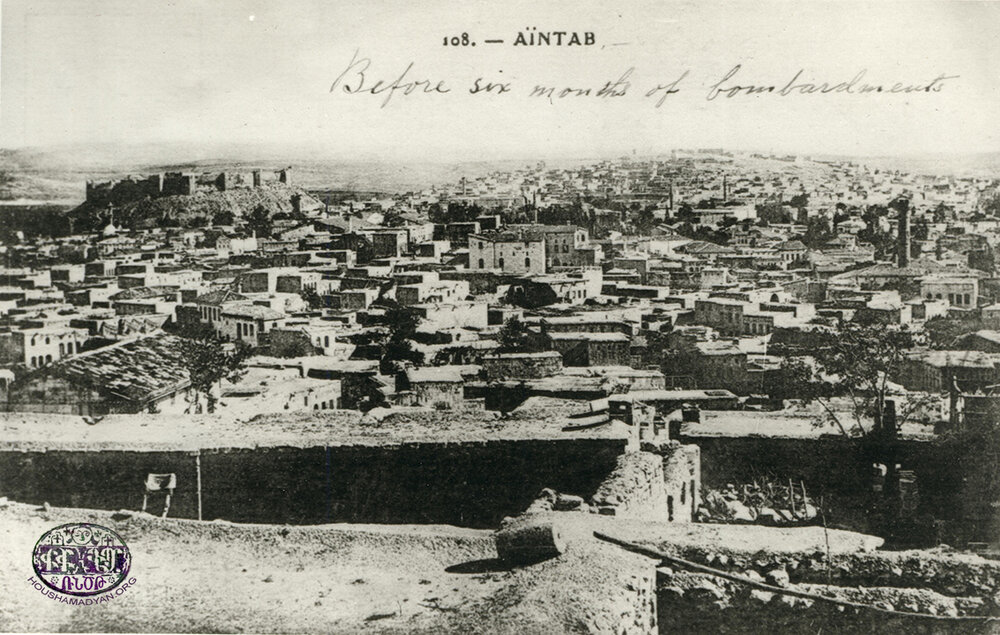

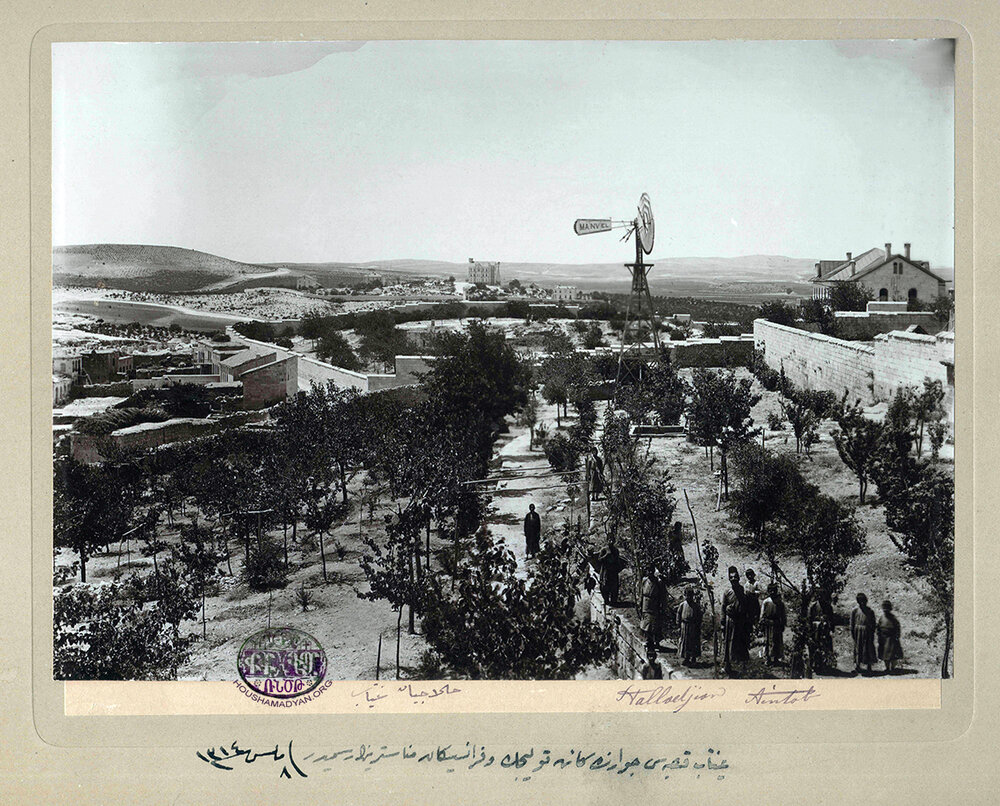

The historic Armenian-populated city of Ayntab, on the borders of Cilicia, was famous not only for its educational institutions, art, crafts, commerce, and resourceful and prolific residents, but also for its large cohort of Armenian photographers. In a relatively short period of time, between approximately 1884 and 1921, about a score of Armenian photographers were active in the city. Many of them continued practicing their craft elsewhere after they left Ayntab, including Marash, Adana, Mersin, Aleppo, Baghdad, Haifa, the Damascus area, Beirut, the United States, etc.

The growth of photography in Ayntab, compared to other provincial Ottoman areas, was partially predicated on the relative prosperity of the Armenian community of the city, as well as the presence of foreign institutions there, with whom the locals interacted and from whom they gained knowledge and experience.

It is well-known that during the years of the Genocide, the Armenian community of Ayntab suffered fewer losses than Armenian communities elsewhere. A large number of Ayntab Armenians, alongside their property, survived. These survivors were able to take a large number of photographs with them when they emigrated. Today, countless such photographs are preserved in archives and museums across the world, as well as in private and family collections. These pictures offer us a glimpse into the past, and not only the recent past, of Ayntab Armenians; and into the work of Armenian photographs there and the high quality of their products.

Photographers in the early 20th century customarily glued their photographs to thick pieces of cardboard, which also served as frames. At the bottom, on the cardboard stretching beyond the edge of the photograph, they usually printed their own name. Sometimes, their location (city) would also be included. Similarly, the back of these cardboard frames would feature beautiful patterns, reproductions of prizes or medals won in exhibitions and competitions, as well as the photographer’s name and location, often in multiple languages. Some photographers who did not have printed cardboard frames would simply hand-write their names and imprint their stamps on the front or back of their cardboard frames. These markings tell the story of the photographs, indicating location and approximate date, as well as other details.

This practice of gluing photographs to cardboard frames survived into the 1920s. It was used in later years only in rare cases, such as “official” photographs.

Unfortunately, not all photographers had their own unique cardboard frames, as it was an expensive luxury. The printing was mostly done in Constantinople or in Europe, in locations like Vienna, Paris, etc. Many of the extant photographs we have examined lack a photographer’s inscription, stamp, or printer’s mark. As a result, all traces of the photographers are lost, and we are unable to identify them and to give them the credit they deserve.

Today, as we examine these photographs, a whole past world comes to life before our eyes. They are living witnesses of the former glory of thousands of destroyed Armenian churches, monasteries, historic monuments, schools, and homes in Western Armenia, Cilicia, and Asia Minor. They are the visual history of Armenian traditional attire, customs, rituals, crafts, daily lifestyle, and countless relics that have been lost to time.

***

The French translation of an abridged version of this article appeared, under the title “Les photographes arméniens d’Ayntab et de la Cilicie : Bref aperçu,” in the book Les Arméniens de Cilicie: habitat, mémoire et identité (Université Saint-Joseph Press, Beirut, 2012, pp. 134-167).

A Review of the Literature on the Armenian Photographers of Ayntab

It would not be an exaggeration to say that until the expulsion from Ayntab of its Armenian population, Armenians there had a complete monopoly over the profession of photography in the city. Until the year 1921, not only single non-Armenian photographer practiced in Ayntab.

Any investigation into the history of Armenian photography faces serious challenges, foremost among which is the scarcity of surviving photographs, the lack of access to those that have, and especially the scarcity of other studies into the subject, with a few notable exceptions.

Engin Özendes, a Turkish expert on the history of photography during the Ottoman era, in her seminal work, Photography in the Ottoman Empire 1839-1923 [1], provides a list of photographers who practiced in Ottoman Ayntab. The list includes seven names, all of whom are Armenian. Four of the names are from Kevork A. Sarafian’s book dedicated to the history of Ayntab, which we will discuss further. The fifth name is Haroutyun Mardigian, who practiced photography in Damascus from 1890 to 1892, and in Jerusalem from 1894 to 1913. We believe that his inclusion in this list was erroneous. We also believe that the name of Krikor M. Msrlian (1853-1932) was included erroneously, as he practiced exclusively in Aleppo from 1880 until his death, and there is no evidence indicating his presence in Ayntab. As for the seventh and final Armenian photographer listed by Özendes, we will discuss him in some detail in the last section of this article.

Another important source of information on the subject is an album published by the Gaziantep (present-day Ayntab) city administration in 2007, on the occasion of a photographic exhibit organized under the title of “A Photographic Exhibit of Historic Gaziantep”. The album includes 70 historical photographs, the majority taken between the 1920s and 1950s. The album does not list any Armenian or non-Armenian photographers active in the city until 1920 [2].

A third noteworthy work on the subject is the seminal book Armenian Photographers by photographer Vahan Kochar. The book provides the individual biographies of hundreds of historical and modern Armenian photographers who worked across the world, alongside examples of their works. Although this is the most comprehensive work ever published on the subject, it provides little information on the work of Ottoman-Armenian photographers, or more generally western Armenian photographers. From all of Cilicia, only the name of Hagop Terzian is mentioned, as the author of a monograph on photography. No photographers from Ayntab are mentioned [3].

Our principal sources of information on the Armenian photographers of Ayntab remain the two-volume Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots [History of the Armenians of Ayntab], edited and compiled by Kevork A. Sarafian [4]; as well as various issues of the periodical Hay Ayntab [Armenian Ayntab] (Nor Ayntab [New Ayntab], beginning with the 44th issue in 1971). The latter was founded in the 1960 in Arlington (Massachusetts), in the United States, and was then moved to Beirut and is still being published today [5]. The periodical was edited by Krikor Bogharian, and published several pieces indirectly pertaining to this article’s subject. Some information on Armenian photographers also appears in the books dedicated to the battles fought during the siege of Ayntab, as well as the memoirs of survivors of these events.

We also gleaned some information from Dickinson Jenkins Miller’s “Armenians and the Growth of Photography in the Near East (1856-1987),” a final dissertation presented to the American University of Beirut. However, this dissertation cites Sarafian’s above-mentioned work for all of the information it presents.

According to one survey, throughout its existence from 1880 until its closure, the Central American College of Turkey of Ayntab had 424 graduates, approximately 2.5 percent of whom would later choose photography and photoengraving as professions. This translates into 10-11 graduates who later became photographers [6]. These probably included both natives of Ayntab and students who came from other regions, as we will see below.

The Armenian Photographers of Ayntab

We will now provide short biographies of individual Armenian photographers who were active in Ayntab, in order of chronology.

We must emphasize that this is not an exhaustive list. We are certain that there were other Armenian photographers whose works were either not preserved, or were not available to us. We must also add that in most photography studios, aside from the master, one or two apprentices also worked. Therefore, the true number of Armenian photographers in Ayntab must have been much larger than the list presented here.

Some of the facts we provide here on Ayntab’s Armenian photographers may not seem particularly essential biographical information, but due to the scarcity of primary sources, we lack more comprehensive accounts of their lives. We have been forced to provide what little information we have been able to gather.

Some Armenian photographers were active in areas that neighbored Ayntab, like Aleppo or other nearby cities. It is difficult to ascertain if these individuals also practiced in Ayntab. We have still listed them here, in order to provide a more complete picture of the contributions that Armenians made to photography in the Ottoman Empire. It cannot be ruled out that these individuals practiced their craft in Ayntab, too, and we simply lack the data to confirm this.

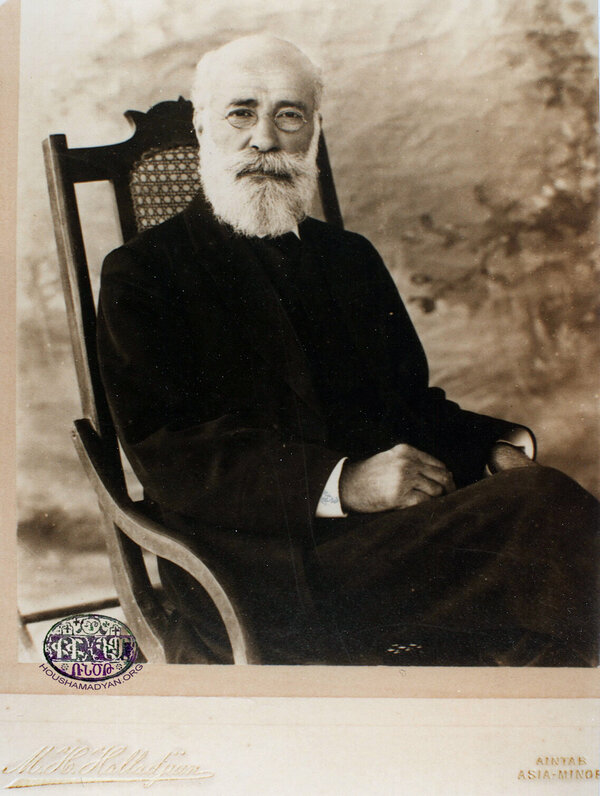

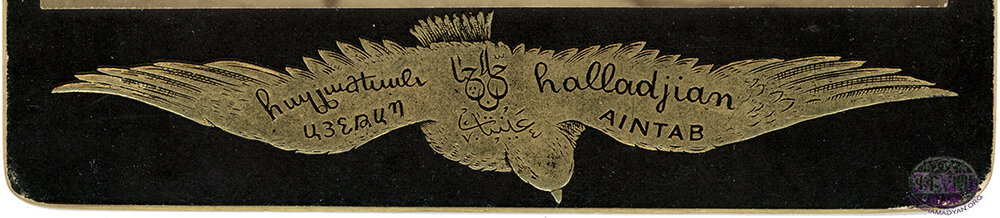

1. Hovhannes Haroutyun Halladjian-Hovhannesian

The Halladjian family belonged to Ayntab’s Armenian Evangelical community. They are also listed under the name “Hovhannesian” in the government registers and certain Armenian sources. This seems to have been the family’s original surname, which was later changed to Halladjian [7].

Hovhannes Halladjian was the son of Very Reverend Haroutyun Halladjian-Hovhannesian. The reverend had founded, and had for many years operated, an orphanage/workshop in Ayntab, known as the Halladjian Orphanage-Workshop. Hovhannes’ mother was Lucia Mamian-Haroutyunian.

Hovhannes was born in Ayntab on April 28, 1867. In 1877, he graduated from the local Asdvadzadour Khalfa School, after which he and his family went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. In the same year, he visited Beirut, to which he returned often afterwards, with a last visit in 1912 [8].

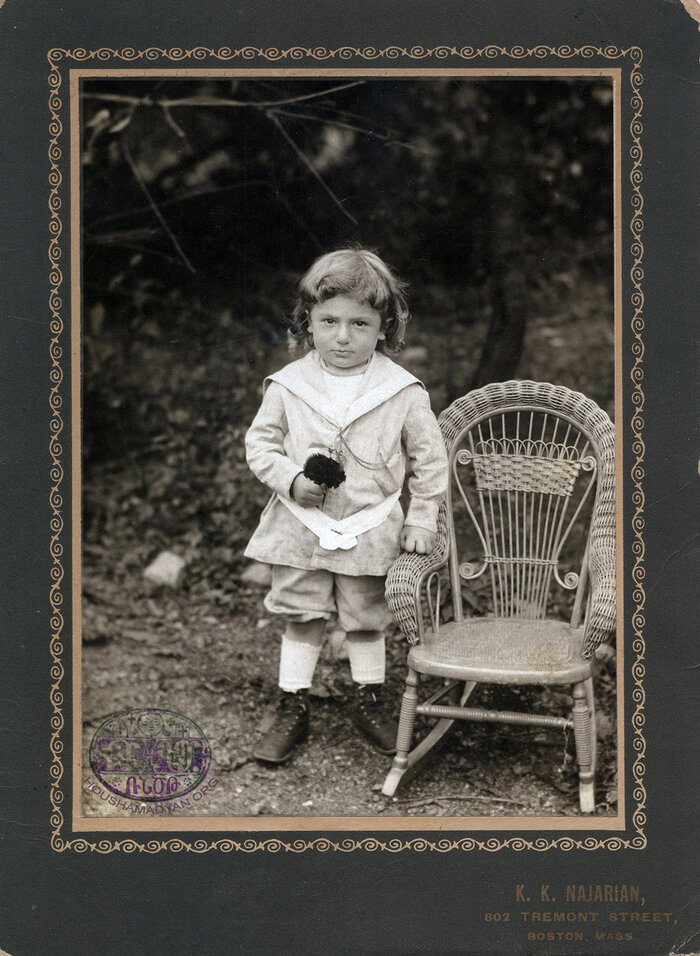

In 1883-1884, he learned photography from a renowned French master. Then he returned to his birthplace, and between the years 1884 and 1894, for 10 years, practiced photography there. For that entire decade, he was the city’s only photographer. “In Ayntab, the art of photography appeared for virtually the first time in 1884…”, states Very Reverend A. Halladjian, of the same family, in his small monograph about photography in Ayntab [9].

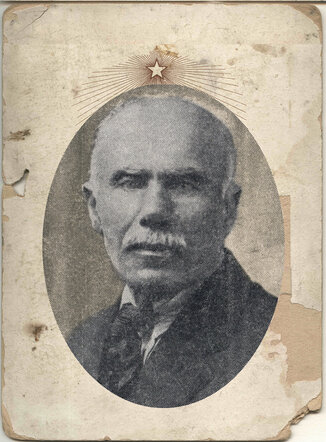

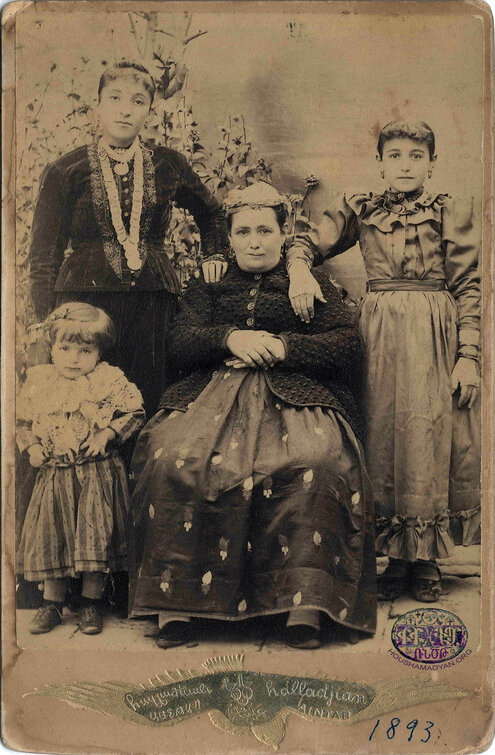

1) The Babigian family, Ayntab, 1893.

The child on the left is Yernig Babigian, who later married photographer Mihran Halladjian. The girl standing behind her is Makrouhi Babigian, the seated woman is Yeghisapet Babigian, and the girl on the right is Eliza Babigian (later Sulahian).

Photographed by Hovhannes Halladjian (Source: Mihran Minasian Collection).

2) An unidentified couple from Ayntab, 1880s or 1890s. The woman is holding a hookah. Photographed by Hovhannes Halladjian (Source: Mihran Minasian Collection).

Hovhannes Halladjian was a polyglot. Through self-education, he had become fluent in several languages. He could read, speak, and write Armenian, Turkish, Arabic, Farsi, English, French, German, Greek, Italian, and Russian. He had a love for photography and thanks to his knowledge of foreign languages, he had developed his knowledge of the craft by reading journals and books published in Europe, keeping up with the latest innovations and staying abreast of the newest developments. He regularly obtained modern photographic equipment from England [10].

He worked as a photographer in Ayntab until 1894. In that same year, he left for Adana and Mersin, and in 1895 he reached Aleppo [11].

A few years later, in 1898, in Ayntab, he was replaced as a photographer by his younger brother Mihran, who had been his apprentice [12].

In the 1890s, in his capacity as a photographer, Hovhannes frequently visited Marash [13], because apparently, there was no practicing photographer in Marash at the time. One of the photographs he took in Marash in 1893 was reprinted in Very Reverend Hampartsoum H. Ashdjian’s memoirs [14].

It remains unclear how he survived the Armenian Genocide and where he spent the years 1915-1918. We only know from ancillary sources that after the expulsion of the Armenian population from Cilicia and Adana, the Halladjians settled down in Aleppo, like thousands of their compatriots [15]. From there, they would later emigrate to other parts of the world.

Hovhannes Halladjian was still living in 1949, in London. From there, he wrote an autobiographical letter to a relative, which concluded with these words: “I will only say this – I never imagined that I would live in this country for so long as a refugee, after having been saved from the ravages of war by the grace of God. I have not taken any photographs for some time, even though I have a good camera. But I have neither the place nor the heart to do it…” [16].

So he had a camera in London, too, but we know nothing of his having worked as a photographer there. We can assume that he practiced photography when he first arrived in London, but that by 1949, due to his advanced age, he had retired.

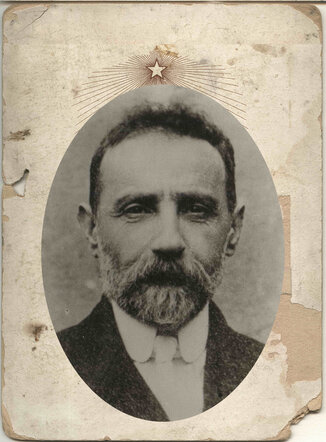

The Reverend Haroutyun Halladjian, the father of photographers Hovhannes, Mihran, and James Halladjians, was born in Ayntab, in 1841. He lost his father at the young age of 20. He studied for some years at the Marash Theological Institute, and then left for the United States and continued his education at Oberlin College (Ohio). He graduated in 1875, after which he traveled to England, then back to Ayntab in 1876, where he founded the Halladjian Orphanage-Workshop.

Reverend Halladjian visited England and Scotland in 1880 to raise funds for his orphanage. He remained there until 1884, returned to Ayntab, and then traveled back to Britain in 1886. On each of his visits, as “living examples,” the reverend took several of the orphans with him, so that foreigners would see them and be spurred to donate generously. Halladjian had also arranged for the orphans who accompanied him to England to learn different crafts (dentistry, leathercraft, brushmaking), so that upon their return, they could practice these crafts in Ayntab.

It is probable that Hovhannes accompanied his father on the first of these trips to England, and that in London he honed his skills as a photographer. Further evidence of this is the fact that he went to Istanbul to further study photography in 1884, and founded his studio in Ayntab in the same year – the year he returned to Ayntab from London.

Reverend Halladjian ran his orphanage singlehandedly for 28 years, after which he retired and handed it over to the three Armenian Evangelical churches in Ayntab. He died in Ayntab, in 1914 [17].

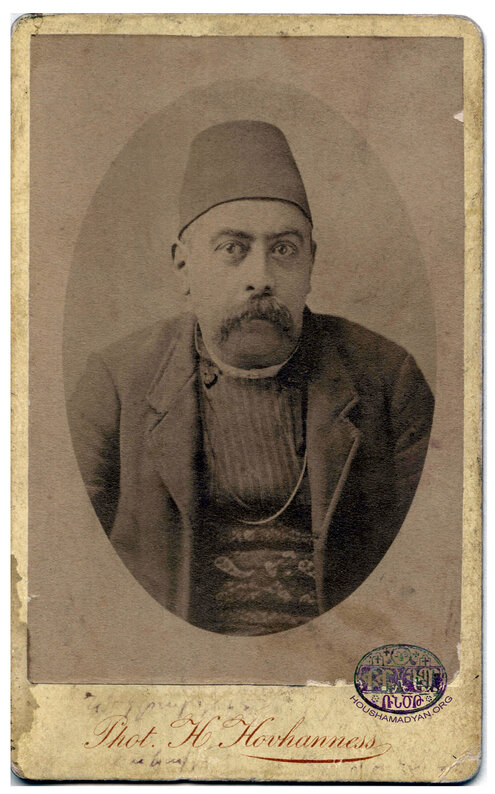

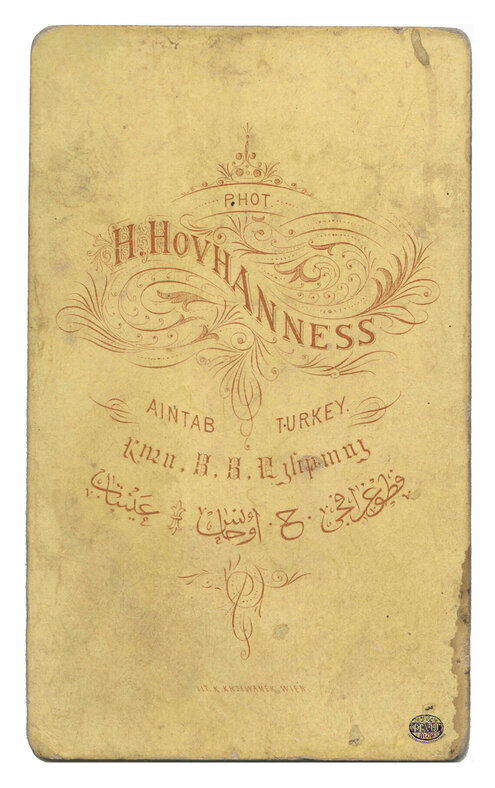

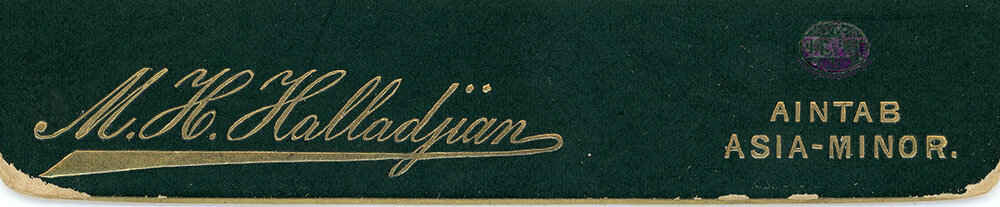

2. H. H. Hovhanness

In our collection, we have a small, old photograph, the front side of which is imprinted with the photographer’s name – “Phot. H. Hovhanness.” The back of the photograph has a trilingual imprint – “PHOT. H. HOVHANNESS AINTAB TURKEY,” in English, Armenian, and Turkish.

We have also seen another photograph, in the possession of a friend, glued onto an identical cardboard frame, bearing the handwritten date 1886-1887.

Another extant photograph with an identical cardboard frame dates from 1887 [18].

We have not been able to confirm that an “H. Hovhanness” worked as a photographer in Ayntab. The large amount of literature on Ayntab’s history, and the literature devoted to the art of photography in the city, make no mention of a person by that name.

These facts force us to conclude that “H. Hovhanness” is none other than the aforementioned Hovhannes Halladjian-Hovhannesian, whose name is provided in some documents and accounts in its abbreviated form – “H.[ovhannesian] Hovhanness.” As we have already noted, the historical literature on Ayntab states explicitly that Hovhannes Hovhannesian “was the only photographer in the city for a period of 10 years” [19] from 1884 to 1894. Our theory is confirmed by the fact that the dates of the three extant photographs taken by H. Hovhanness (1886-1887) correspond to the years in which Hovhannes Hovhannesian was actively practicing photography in Ayntab (1884-1894).

Another question then arises. When Hovhannes Halladjian-Hovhannesian had his own individualized, printed, and engraved photographic frames, why would he have also use a different one? The frames were probably used at different times. Presumably, after he stopped using the name Hovhannesian, he stopped using the older frames and printed new ones bearing the name Halladjian.

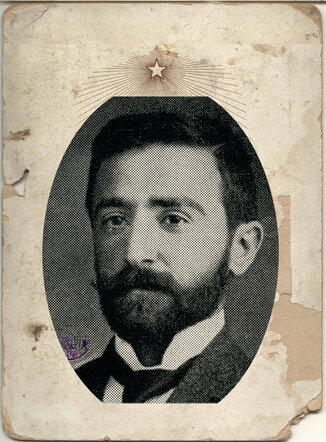

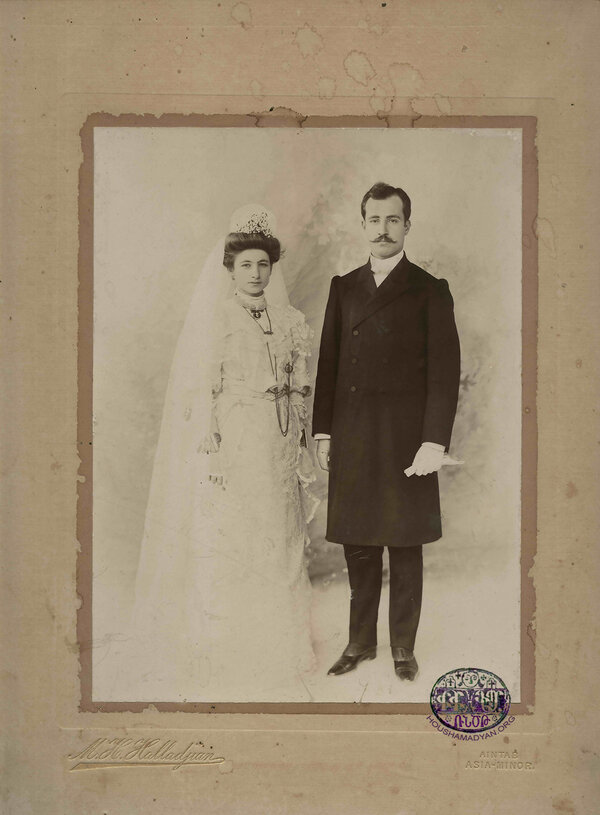

3. Mihran Haroutyun Halladjian-Hovhannesian

One of the best-known photographers of Ayntab. He learned photography as an apprentice to his older brother, Hovhannes. But not satisfied with what he had learned, he traveled to England to hone his skills. He returned to Ayntab in 1898 and took over his brother’s photography business, which had cased functioning in 1894 when Hovhannes had left the city.

On July 30, 1994, in Aleppo, we had the great pleasure of meeting Vahram Babigian, the well-known Aleppine doctor and Mihran Halladjian’s brother-in-law, on the eve of his move to the United States. He provided us with some details regarding the life of his brother-in-law. Some years later, on August 3, 2000, we wrote a letter to the doctor, asking him for additional information on both Mihran and Hovhannes Halladjian. In his turn, the doctor replied with a letter dated September 13, 2000, sent with the late Mr. Vartan Temourian, another Aleppine Armenian. The letter provided additional details on both photographers’ lives.

Here, we provide the information obtained from Dr. Babigian in the aforementioned conversation and correspondence.

Mihran Halladdjian was born in Ayntab, in 1880. He had several brothers, one of whom, Hovhannes, was a photographer. He lived in England for some time. His brother, Samuel, was a reverend and lived in the United States. He had a third brother named James. In Ayntab, his home and his store were adjacent, near the Tepe Bashi neighborhood, on Hayig Baba, near the American hospital. His studio, compared to his home, was small, while the home was large and had its own courtyard.

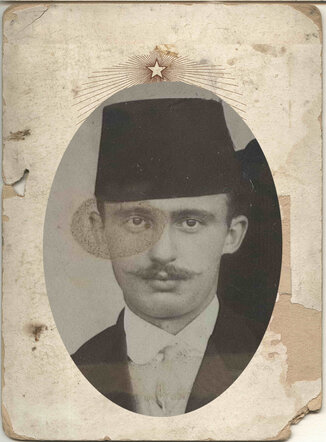

First from the left (young man, standing) is Samuel Halladjian, who later served as an Evangelical reverend in the United States. The seated man is Very Reverend Haroutyun Halladjian. The standing, bearded young man is photographer Mihran Halladjian. Immediately to his right is his wife, Yeranig Babigian-Halladjian. The seated woman is Lucia Mamian-Haroutyunian, wife of Very Reverend Halladjian. At the very right, standing, is probably photographer James Halladjian (Source: Mihran Minasian Collection).

Mihran was married to Yeranig Babigian, a member of Ayntab’s Armenian Evangelical community, born in 1891.

The couple had three children: Yervant/Eddy, Puzant/Ray, and Hermine. Hermine was born after her father’s death. All three children would later marry non-Armenians in the United States, and all three still living as of 1994. Their mother, Yeranig, died in 1982.

Mihran died in Ayntab in 1920, five days after contracting influenza. After his death, thanks to the efforts of Reverend Samuel, his brother who lived in America, his wife and children were able to emigrate to the United States in 1921. The couple’s oldest son was 9-10 years old at the time. He was still living as of 2000, in the United States. Hermine’s daughter also lived in the United States as of that year.

The negatives of the photographs Mihran took were left behind in Ayntab, and were never recovered [20].

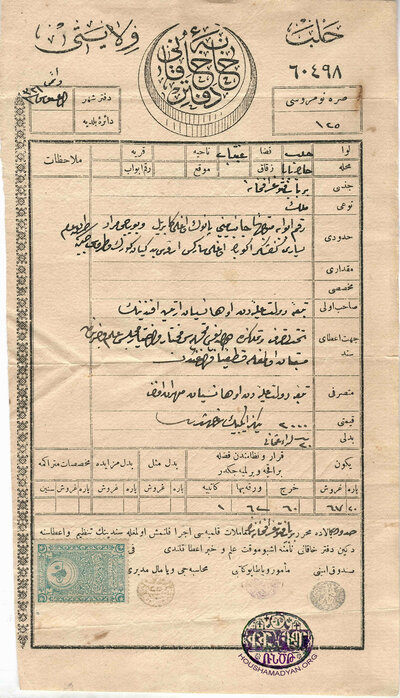

We have, in our possession, the two deeds of Mihran Halladjian’s photography studio. The first was issued in August 1321 of the Ottoman calendar (August 14-September 13, 1905 of the Gregorian calendar), and the second on the 29th of Safar, 1324 of the Islamic calendar (April 14, 1906 of the Gregorian calendar). The documents indicate that the studio was located on Hayig Baba (Heyig) Street of Ayntab. The value of the property was estimated at 2,000 kouroush, or 20 Ottoman pounds. The previous owner was Artin (Haroutyun) Hovhannesian (Halladjian, Mihran’s father), who transferred ownership to Mihran Hovhannesian (Halladjian).

Father and son were Ottoman citizens. The studio was on the main road and abutted, on its right, the store of Kapriel, son of Panoug, and that of the boyadji (painter) Mourad; on its left, the workshop of the cobbler Sarkis, son of Hagop (in the second document, listed as Hovhannes, son of Hagop); and to its rear, the store of Kevork Yedigian.

According to the 1906 deed, Mihran Hovhannesian (Halladjian)’s studio had a size of 1.5 old donums, 13 aouleks, and 78 new arshins. These measurements correspond to about 1,350 square meters (14,531 square feet).

Mihran Halladjian was an erudite, energetic, and extremely pious man. Despite being a member of the Armenian Evangelical community and the son of a reverend, he preached in both Evangelical and Apostolic churches. He was an active member of the Society of Faithful Armenians (“Chrisdosasirats”) from the day of its founding in 1896. Throughout his life, he supported this society’s advancement, often helping it financially.

He was one of the members of the Chrisdosasirats who, alongside a dozen other youth, took a hiatus from his work and studied in various colleges and universities, and after graduating, returned to Ayntab to once again evangelize [21].

A small booklet dedicated to the Chrisdosasirats Society in Ayntab includes the following moving lines referring to its ever-faithful member: “The Lord Jesus Christ took over his heart during meetings of the Chrisdosasirats. With his smile and his generosity, he lived as a true follower of the Good Samaritan. Form Ayntab to Ourfa/Yetesia, thousands of our compatriots heard the message of the Holy Book from his lips” [22].

These lines also show that he preached in both Ayntab and Ourfa.

The sermons he delivered during meetings of the Chrisdosasirats Society made a deep impression on his audiences [23]. He was also a member of the Ayntab scholastic society.

Mihran Halladjian was the official photographer of the Central Turkey College of Ayntab [24]. The yearly photographs of the school’s graduates are presumably all his work.

We do not know how he survived the Armenian Genocide or where he spent the years 1915-1918. We only know that in 1915, he was arrested by the authorities. This is confirmed by the testimony of his cellmate, educator Sarkis Balabanian (Balaban Khodja): “[In Ayntab, in 1915] When they pushed me into the prison cell and locked the door behind me, I found Mihran Halladjian there, who had been brought in before me” [25]. This is all we know, and we have no knowledge of subsequent events. One of his relations, Very Reverend A. Halladjian, stated that Mihran was “not only the best, but also most celebrated photographer in Ayntab for almost 20 years, from 1898 to 1918” [26]. Should we imply from this timeline that he spent the years 1915-1918 in Ayntab? Was he one of the fortunate Armenians who were spared deportation because their professional skills were valued by the Turkish authorities?

4. James Haroutyun Halladjian-Hovhannesian

James was the third Halladjian brother, and he practiced photography in Mersin, Haifa, Damascus, and the areas surrounding these cities. He practiced as far as Jordan and even further south, to the northern reaches of present-day Saudi Arabia.

We have already mentioned that Hovahannes Halladjian practiced photography for some time in Mersin. He probably either worked alongside James, or replaced him.

We have been able to obtain a photograph taken by James in Mersin, probably in the early years of the 20th century. The cardboard frame bears the imprint “J. H. Halladjian MERSINE Asia Minor.”

James was one of the official photographers of the Hijaz (Arabian) railway project, documenting the work. He had probably received this commission from the official authorities or the railway company. The photographs he took in 1908 of the railway and the areas it crossed have survived, featuring Damascus, Tabuk (692 kilometers south of Damascus, now in Saudi Arabia), and further south, Madaen Saleh and Al-Akhdar.

5. Kasbar Khodja Pilavdjian-Kzarian

He was the famous Kasbar Khodja of Ayntab, the father of the late Archbishop Shahe Kasbarian (1882-1935).

He was born in Ayntab. Three different sources give three different years as that of his birth – 1845, 1850, and 1855. The first seems the most logical to us, as other sources indicate that in 1886, he was a practicing teacher in his hometown, and it seems unlikely that a teenager of 11 (or 16) would be appointed to such a position.

Presumably, he was a pupil of the teachers Abraham and Mourad Mouradian.

He was well-versed in the psalms and devoted himself for an entire half-century to Armenian music and the Armenian church, as the choir master and music teacher of the local Holy Virgin Church. He had learned Armenian musical notation and playing the organ from Master Boghos Kurkdjian (from Marash) and Master Hagop (from Constantinople).

In 1892, he founded the church choir of the Holy Virgin Church of Ayntab, and over the years helped shape countless choirmasters and music teachers. In the 1880s, he served as a choirmaster in Adana [27]. He gave private church organ and violin lessons to local Armenians and Turks. Kasbar Khodja was the composer behind the Vartanian School’s “Der Zoroutyants” and “Aha Asdghn Vartanian” and the Atenagan School’s “Harach Sanounk!” marching songs, as well as many variations of “Der Voghormia,” that were only performed in Ayntab [28]. He also composed music for many poems, mostly works of Ayntab poet Armenag Nazaretian (A. Nazar), such as “Yerk Ar Vartanyank” and others.

During the years of the Armenian Genocide, he and his family found refuge in Beredjig, where he worked at the local shipyard and was thus spared deportation into the desert. In 1919, he returned to Ayntab, and in the following year he made his way to the United States, where he also served as a choirmaster for some time.

In 1919, he received an invitation from the Prelate of the Armenian Diocese in Egypt, Archbishop Torkom Koushagian, to relocate to Cairo and serve the church there. However, he declined the offer.

Kasbar Khodja was endowed with multiple talents. While still in Ayntab, he also practiced photography. The Ayntab Chronicle confirms that “aside from his musical talents, he also practiced photography” [29].

He died in the United States, on November 24, 1936 [30].

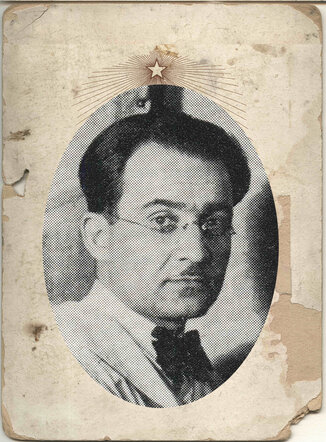

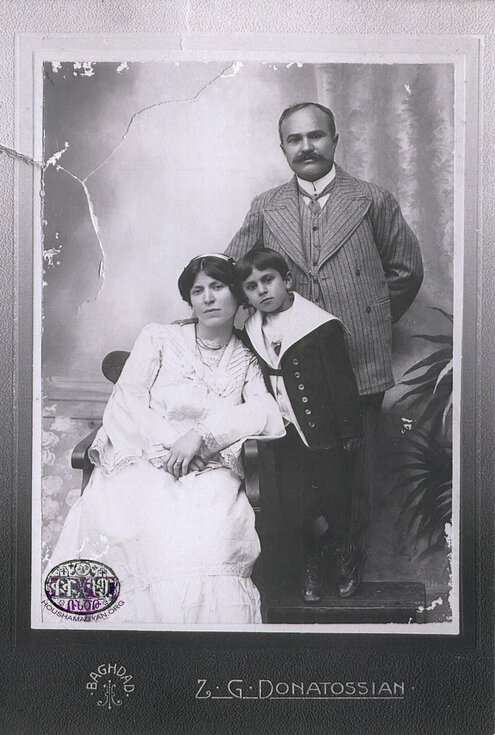

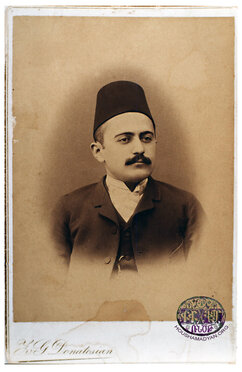

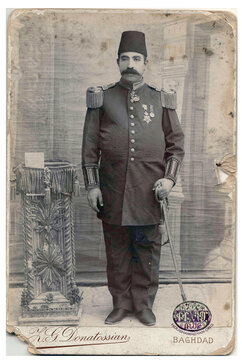

6. Zorapapel Krikor Donatosian

A renowned photographer, he was considered one of the best at his craft by his contemporaries. He had practiced in Baghdad in the early years of the 20th century.

As a photographer, Donatosian lived and worked in various cities, including Ayntab, Erzurum/Garin, Constantinople, Basra, and perhaps also Arapgir, Izmit/Nicodimia, and other cities. Eventually, he settled down permanently in Baghdad.

In 2005, we asked the late Mr. Barouyr Orchanian, head clerk of the Baghdad Armenian Prelacy, for biographical information on Donatosian. Mr. Orchanian sent us a short biography, copied from the prelacy’s registers. We present this information below.

Doantosian was a member of the Armenian Evangelical community. Still, he was registered and included in the records of the Armenian Apostolic community, where his registration number was 132, and according to which he was born in 1870 and emigrated to Iraq in 1896. By profession, he was a photographer. He married Takouhi Garabed Takvorian (born in 1884) in Izmit in 1904. In the same year, they left together for Baghdad.

In 1915, alongside 40 other Armenians, Catholics, Jews, and Tajiks, he was arrested by the authorities and exiled from Baghdad to Mosul. Then orders were immediately sent from Baghdad to send them into the mountains of Dersim, separate them, and disperse them in different villages. But thanks to the intervention of the Chaldean patriarch of Mosul and a Turk named Sabandji, they were kept where they were. Later, again thanks to the patriarch, they were returned to Baghdad and were kept in the military prison until their eventual release [31].

They had a son, Levon, whose registration number in the records of the Baghdad Armenian Prelacy was 260. Levon later married Christine Hagop Chinarian, an Armenian Evangelical from Baghdad.

Zorapapel died in 1926, in Baghdad, and was buried by his fellow Evangelicals in the English Cemetery in the vicinity of the city’s Armenian cemetery.

As we have already noted, Donatosian was active in several cities. It seems that he started including the name of the city of Baghdad on his picture frames only after settling down there. In the frames he used while in other cities, no location was mentioned. Perhaps this was a deliberate decision, given his peripatetic life and his frequent wanderings.

We have evidence that for some time, he lectured at the Ayntab Seminary. This was after 1882, when this institution began hiring graduates of the Central Turkey College as lecturers. His name is mentioned among these lecturers, but we could not find it in the list of College graduates [32]. He probably attended the college but never graduated. We don’t know much about the time he spent in Ayntab, his years as a student, work as a teacher, or work as a photographer. We also don’t know what subject he taught at the Seminary.

We have seen two photographs that are Donatosian’s work, taken in the 1890s and glued onto cardboard frames that bear his inscription. The owners of the photographs assure us that they were taken in Ayntab. We have also been told that the people appearing in the photographs never traveled outside of Ayntab.

Another intriguing episode from Donatosian’s life occurred in the city of Erzurum. During Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s reign, master photographers were dispatched to various corners of the Ottoman Empire to photograph landmarks, residences, and architectural features. One of these photographers was Zorapapel K. Donatosian, who photographed many of Erzurum’s landmarks, including mosques, Muslim tombs, palaces, barracks, official buildings, markets, springs, panoramas of the city, etc. These photographs (or perhaps only some of them) later appeared in a Turkish-language album called Gravür ve eskı fotoğraflarla Erzurum, or Erzurum in Gravures and Old Photographs. The album was compiled by Erol Kılıç, and published by Ataturk University of Istanbul in 1988. The photographs numbered 39-84 are Donatosian’s work. According to the same book (page 17), these are the oldest known photographs of Erzurum.

Some of the photographs that appeared in this album were also later reproduced in Istanbul’s Sourp Prgich [Holy Savior] monthly magazine [33].

It is unclear whether Donatosian ever established his own photography practice in Erzurum or if he worked exclusively for the Sultan. We also don’t know if the trip to Erzurum was the only time he received a commission from the Sultan in his capacity as a photographer, or if he was also dispatched to other areas.

For some time, Donatosian practiced photography in Constantinople.

In 1896, we find him in Baghdad. He had worked for some time in Basra, but then settled down permanently in Baghdad, where he established his studio on Khalil Pasha Street (later renamed Rashid Avenue).

Donatosian is considered the first established photographer in the history of Iraq [34]. Many examples of his photographic works have survived and are accessible to us.

In 2005, via Mr. Nazar Ohanian, who formerly lived in Iraq and currently resides in the United States, we received copies of several interesting Donatosian family photographs from Sella, son of Donatosian’s grandson, Levon. We present those photographs here to our readers. We would like to take this opportunity to express our gratitude to Nazar.

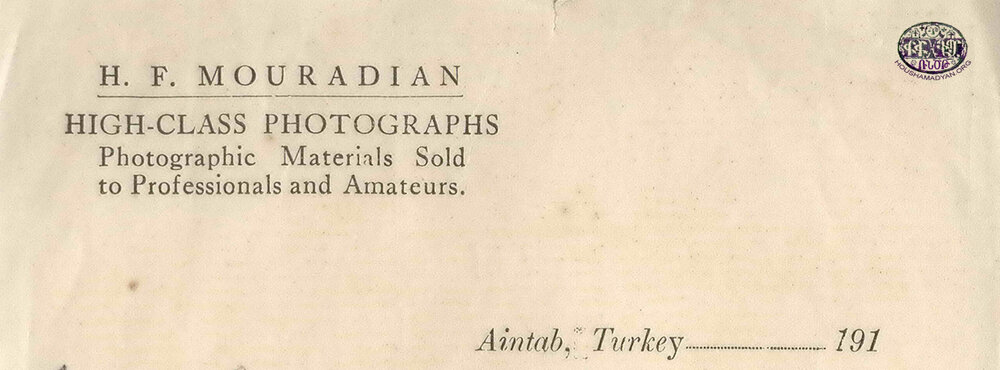

7. Hagop F. Mouradian

Hagop Mouradian was a well-known photographer and community activist in Ayntab. He matriculated at the local Central Turkish College, from which he graduated in 1892 [35]. Therefore we can assume that he was born around 1872. Apparently, he opened his photography practice soon after graduating from the college, because we have examples of his photographic works from 1895, 1896, and the following years.

In a list of Central Turkish College graduates dating from 1909, Mouradian is listed as living in Boston, Massachusetts, and as a practicing photographer [36]. We have not been able to discover the precise dates of his departure for and return from the United States, or any additional details about the time he spent there.

From the letterhead of the correspondence we have from Ayntab, it is clear that Mouradian was not only a high-class photographer, but also a consummate professional and a supplier of photographic equipment to amateurs.

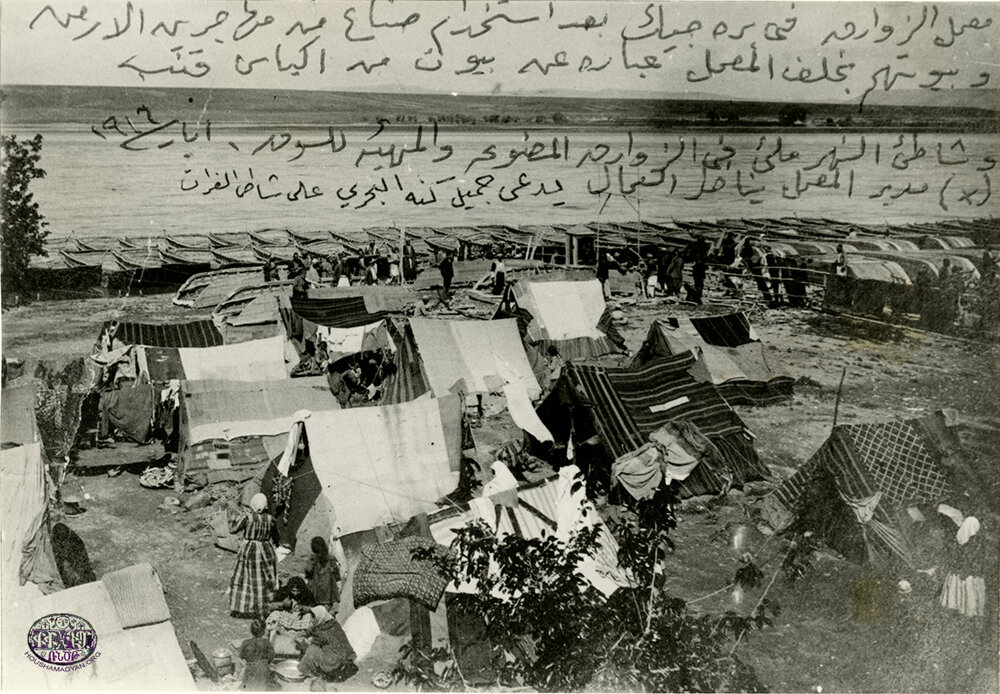

In Ayntab, before 1915, he was an active member of the community. During the years of the Genocide, he fled to the city of Beredjig on the shores of the Euphrates, not far from his hometown, and worked in the carpentry department of the government shipyard [37]. We know that the shipyard operated in the city throughout the years of the war, under the management of a Kurd, Djamil Kenne Bahri, who was married to Dikranouhi, the daughter of Ayntab’s interim prelate, Father Garabed Guluzian. Bahri employed a large number of Armenian refugees, mostly from Ayntab, as craftsman in his shipyard, saving them from deportation into the desert.

An interesting document has been preserved for posterity – a letter, dated February 22, 1919, written in Turkish but using the Armenian alphabet, from Mouradian’s wife to her brothers, the Kharadjanians (who probably lived in the United States). In the letter, she expressed her gratitude to God for giving her the opportunity to write to her loved ones one more time, and gave an account of her family’s ordeal over the previous four years. The fact that the Mouradians were American citizens had only caused them additional trouble. They had been deported to Deir Zor, while the other Armenians of Ayntab were mostly deported to less dangerous areas, like Hama and Salamiyeh. The Mouradians, reaching Beredjig, had been able to remain there thanks to the intervention of a government official (perhaps the above-mentioned Djamil Kenne Bahri, director of the shipyard). They lived on the banks of the river for eight months, in a tent, until they were finally able to move into the city, where they lived for two years. They slaved away in the shipyard but received no pay. Moreover, Hagop Mouradian was forced to part with his photographic equipment, worth about 150 Ottoman pounds. It was used to bribe government officials. On their way from Beredjig to Aleppo, they were attacked, robbed, and escaped death by a hair’s width. They finally reached Aleppo just a few weeks before the liberation of Damascus (October 12, 1918) [38].

This suggests that Mouradian practiced photography during the war years, in Beredjig. We think it likely that the several beautiful photographs of the Beredjig shipyard, its supervisors, and its Armenians workers, which have been oft reproduced and circulated, are the work of Hagop Mouradian [39].

There is also evidence that as early as February 1917, the Mouradians attempted to receive permission to move to Aleppo from Beredjig, through the intervention of the American embassy. Evidently, the request was denied [40].

An interesting anecdote about Hagop Mouradian’s years in Beredjig has been passed down to us. The teenager Krikor Sudjian, a native of Boursa, reached Beredjig on the verge of death. In a garden near the city, he found another refugee teenager like him, who said: “There is a committee that looks after people like us, those who have been abandoned to starve. It’s made up of Ayntab Armenians who live in the tents on the banks of the Euphrates. They work secretly from the government. They’re all government workers. The head of the committee is Hagop Efendi Mouradian.” Led by this teenager, two others carried Sudjian to the tents of the refugees. On Mouradian’s advice, they fed him, and Sudjian asserted that “thanks to the care and conscientiousness of the committee, I am gradually getting better and coming back to life” [41]. Sudjian stayed in the Mouradians’ tents for three months. In his memoirs, Sudjian adds that he never saw or heard of the Mouradians afterwards, until decades later, Krikor Bogharian published an interview with him in Hay Ayntab (a book edited by Bogharian). Mouradian’s wife, Mary, who remembered Sudjian and the aforementioned events, read the interview in the issue of January 21, 1968, and sent a letter from the United States to Sudjian, expressing her joy at having found him again, and reminding him of several events that had occurred in Beredjig [42].

Let us return to Aleppo. Immediately following the Armistice, on December 19, 1918, Mouradian became a member of the Aleppo Armenian National Union, as a representative of the Evangelical community. His active participation in the committee’s work was instrumental. He was trusted with several sensitive tasks, all of which he accomplished dutifully.

In February 1919, Mouradian was a member of the Union’s philanthropic committee. He was the committee’s treasurer, and responsible for distributing aid to the refugees who had found refuge in Aleppo. In August 1919, he and another member of the Union, Father Kapriel Kasbarian, traveled to Ayntab, in order to revive the local chapter of the Armenian National Union, which had been dissolved; and to resolve certain issues related to the chapter’s operations. They successfully achieved their mission and returned to Aleppo. On another occasion, he was dispatched to Kilis, with the same mission of resolving issues related to the local chapter of the Armenian National Union.

Mouradian served the Aleppo Armenian National Union with great generosity at a crucial time in its history, until he “was forced to leave Ayntab by extraordinary circumstances.” In November 1919, he resigned from the organization and moved back to his hometown, where on January 10/23, 1920, he became a member of the local chapter of the Armenian National Union, again representing the Evangelical community. Some time later, he served as the chapter chairman during the fateful days of the city’s siege.

In May 1920, he left Ayntab and returned to Aleppo. In 1921, he returned to Ayntab, was once again elected to the Union, and one again served as its chairman [43].

Many of the photographs taken of the battles during the siege of Ayntab in 1920-1921 are Mouradian’s work. The photographs feature his name, Mouradian, imprinted in the lower right corner.

In later years, Mouradian emigrated to the United States and worked as a carpet merchant. He died in 1941.

8. Attar Yeghia – Yeghia Attarian

His real name was Yeghia Attarian, but he was better known as Attar Yeghia. He served as the deacon of Ayntab’s Anglican church.

In 1915, like many of his compatriots, he and his family were deported to the Syrian city of Salamiyeh. In the autumn of 1918, he made his way to Aleppo, where he stayed until 1920. In that year, he emigrated to Boston, in the United States, thanks to the financial assistance of the Israyelian sisters, who happened to be close relations of his. He was the father of Barkev Attarian (1900-1936), author of several collections of poetry [44].

One source mentions that in Ayntab, “in addition to running a small retail business, [Attar Yeghia] also worked as a photographer” [45].

9. Zadig Kouzouyan-Kouzian-Gouzougian

He was born in Ayntab in 1875 (or 1871, according to another source). We do not know when he left Ayntab. However, he is mentioned in the register of Aleppo’s Armenian Prelacy in 1910 and 1911, on the occasion of the baptisms of his twin sons. The register also mentions that he was a photographer by profession.

He was still living in Aleppo in 1913. In that year, he was included in the census of Armenians in Aleppo, and his age was given as 38 (suggesting that he was born in 1875). He was listed as a native of Ayntab and a practicing photographer. At the time, his wife (Nartouhi) was 27 years old, and his daughter, Eliza, was 13 years old [46].

In 1920, he was in Baghdad, where he also worked as a photographer. We do not know when he moved there from Aleppo [47].

We have obtained an interesting document that mentions his name. It is a letter by Father Haroutyun Yesayan, the interim prelate of the Aleppo Armenian Prelacy, addressed to the Baghdad chapter of the Armenian National Union, dated October 2, 1920, and numbered 565. In it, the interim prelate informs the Union chapter that Zadik Kouzouyan, 49 years old, and a native of Ayntab, had changed his name and was living under an assumed identity in Baghdad, “cohabiting with a woman, either married to her or out of wedlock,” while his legitimate wife and three children were left behind in Aleppo, in extreme poverty. In order to make it easy to recognize him, the interim prelate provided a physical description: “a blond mustache, relatively corpulent,” etc.

Father Yesayan hoped that the Baghdad parochial authorities would track down this “heartless” man. He went on to say that since sending him back to Aleppo was not a possible in those days (due to the fact that the roads were closed), he hoped the Union chapter would force him to pay a sum of money which they could then transfer to his legal wife; and “chase that immoral woman from his side.”

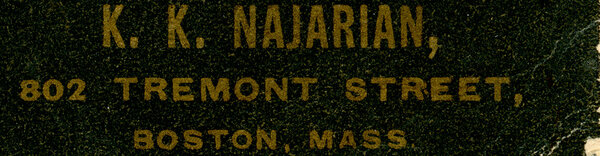

10. Kasbar Nadjarian

He was born in Ayntab, in 1880, and later emigrated to the United States. We do not know if he practiced photography while still in Ayntab. We have obtained a photograph that he developed in his studio in Boston, around 1910, but we have not obtained any similar examples from his time in Ayntab.

Nadjarian was a renowned Armenian-American artist and photographer. In his studios in Boston, Fresno, and Los Angeles, he photographed many famous Armenians either visiting or living in the United States, eventually amassing a very rich catalogue. He also photographed U.S. presidents. From very early only, he actively participated in community life – in the church, socially, and as a member of an Armenian political party. He married and provided his children with university education [48].

He was still living as of 1938.

11. Nerses K. Nigoghosian

The archives of the Prelacy of the Peria Diocese include a document dated September 13, 1913, and sent from Ayntab. It is signed by of Nerses K. Nigoghosian. The letter was sent to the interim prelate of Aleppo, Father Haroutyun Yesayan. In the letter, Nigoghosian petitions the interim prelate to secure employment for him as a teacher in Aleppo or elsewhere in the following academic year; or, if such a position was not available, to secure him a position as a clerk with one of his acquaintances. Nigoghosian states that he is seeking employment because “this year, there has been little work for photographers.”

We have no other information on Nerses Nigoghosian. Evidently, he practiced photography in Ayntab, and had decided to leave the city to pursue better opportunities elsewhere.

12. Dikran Ilvanian

Photographer and painter. He was born in Diyarbekir. In his youth, his family moved to Ayntab, where he received his early education. In 1905, he graduated from the city’s Central College of Turkey. He displayed early interest in painting and began drawing with charcoal. His talents were appreciated by those around him, and on the advice of family friends, he was sent to Aleppo to apprentice with a master painter. He stayed in the city for several years, then returned to Ayntab and produced “paintings of fields with beautiful colors.” He taught painting in several schools, including the Atenagan School, and appears in a 1907 photograph of the school’s faculty. One of his pencil drawings adorned the Holy Virgin Church of Ayntab, and was highly cherished by the locals. He was one of the victims of the Armenian Genocide, deported to Deir Zor. In Ayntab, he worked as a photographer [49].

According to another source, Ilvanian was a graduate of the French College of Beirut [50].

His name appears in the list of graduates from the Central Turkey College, where it is also mentioned that he practiced photography, and that as of 1909, he lived in Ayntab [51].

He later returned to Diyarbekir and served as the certified translator of the provincial authorities, a teacher at the Idadieh School, and a secretary of the Armenian General Benevolent Union. He was a member of the Ramgavar (Armenian Democratic Liberal) Party. Sources provide conflicting accounts of his death. It is said that like many others, he was arrested in 1915 and subjected to horrendous torture, and then, under the guise of being sent to Mosul, he was marched out of the city and killed along the way [52]. However, according to Teotig: “Under the guise of taking him to Mosul, they set out in carts from the city, and a few hours outside the city, they all drowned in a river…” [53]. His older sister was betrothed to an Ayntab native by the name of Tarpinian. She was abducted in 1915 by a policeman in Diyarbekir, and was still in his captivity as of 1919 [54].

13. Haroutyun N. Boshgezenian

He is included in the list of 1908 graduates of the Vartanian Institute of Ayntab, where it is also mentioned that he practiced photography after his graduation [55].

After graduating from the Vartanian Institute, he worked as a teacher in the village of Bitias, in Mousa Dagh. In May 1912, he was in Tarsus/Darson, and attended the Saint Boghos (Saint Paul) American Missionary College.

According to another source, Vartanian graduated in 1909, and in 1914 he was still a student at the Saint Boghos College [56].

Although sources do not mention where he practiced photography, he most probably worked in Ayntab, perhaps until the First World War or the years following the Armistice.

He should not be confused with the renowned legal scholar of the same name, also a native of Ayntab (1861-1923), who lived in Aleppo and served as a representative of the Aleppo province in the Ottoman parliament.

14. Levon Darakdjian

A native of Beredjig. At the time of the Armistice, he was working as a photographer in Ayntab. The only evidence we have of this is a testimonial by Khoren Tavitian, a native of Zeytoun and an acquaintance of his, who stated in his memoirs that Darakdjian “worked as a photographer” in Ayntab, and had sold a camera to a Turk, having received half the price up front, and on condition that the second half would be paid at the end of the month. The Turk had reneged. Darakdjian had resorted to suing him, calling Tavitian as a witness. Fortunately, Darakdjian had won the case [57].

Darakdjian left much more of a trace in White Plains, New York, the United States, where he also worked as a photographer. Khoren Tavitian found him there, and was photographed, alongside his wife, by him. He then included the photograph in his memoirs, adding that it was “his favorite of all his photographs” [58].

15. Albert Bezdjian

A native of Ayntab. He was included in the list of 1915 graduates of the Central Turkey College. The list states that he began working as a photographer upon graduation [59], but it does not specify whether in Ayntab or elsewhere.

16. Dikran Sebouh Chakmakdjian

Photographer and painter. He was born in Ayntab on May 6, 1894. He received his primary education at the local Haygazian School, then moved on to the Vartanian Institute, from which he graduated in 1912. While there, his painting teacher was the renowned art scholar Sarkis Khachadourian. Upon leaving Vartanian, he attended the Cilicia Lyceum for two years.

From an early age, he loved painting. In his years as a student in Cilicia, he won a painting competition, and later worked as the painting teacher in the Education Ministry’s school in the same city until his deportation [60].

In Ayntab, he painted two paintings for the local Holy Virgin Church, Christmas and Holy Resurrection. After the expulsion of the Armenian population of the city, the paintings were taken to Aleppo and handed over to the eponymous church in that city.

In the years of the Armenian Genocide, he and his family were deported to the city of Hama in Syria. There is some information that his father, Sebouh, converted to Islam on June 17, 1916: “Sebouh Chakmakdjian’s conversion is confirmed, in Hama. His son is given a position as a clerk, with a salary of 200 piastres” [61]. The last sentence refers to either Dikran or his brother Kourken, who was also a photographer. Like many others, the Chakmakdjians, too, must have resorted to conversion in order to be spared deportation into the Syrian deserts, returning to the Armenian Apostolic Church after the Armistice.

The Chakmakdjians made their way from Hama to Lebanon, where Dikran was commissioned to paint portraits of Djemal Pasha, the governors of Lebanon and Syria, and Arab grandees. For these services, he received great honors, and used his influence with Djemal Pasha to save the lives of many deported Armenians.

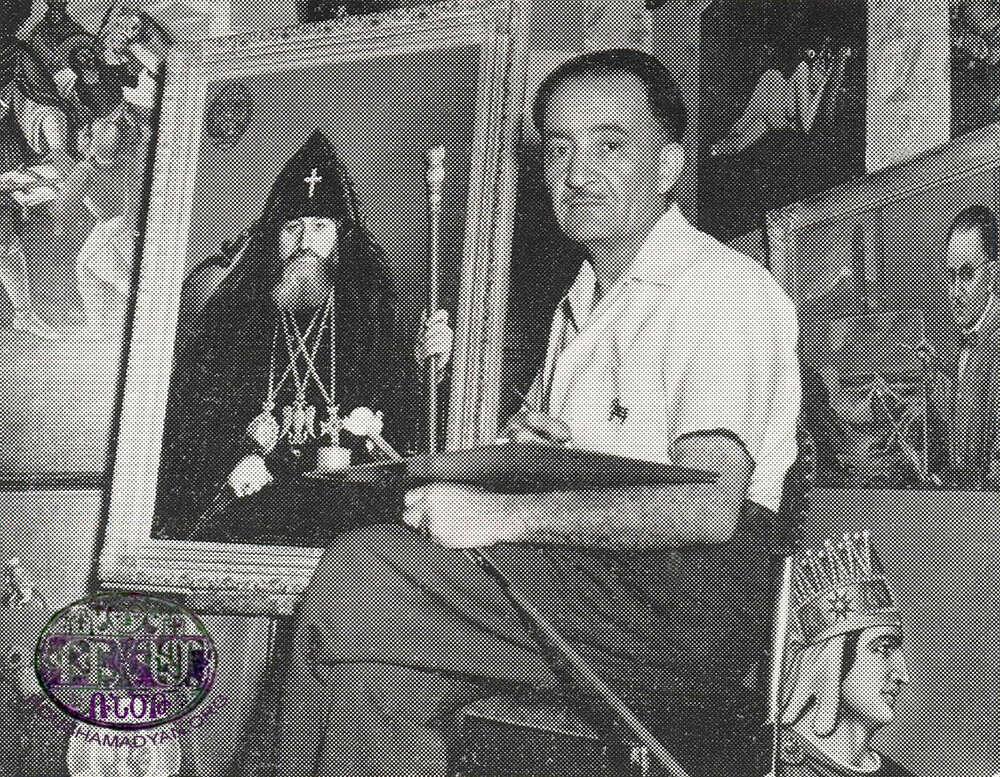

After the Armistice, upon his return to Ayntab, he practiced photography with his brother Kourken. “In 1919, as soon as they were back, the two brothers, Dikran and Karekin, were about to establish a photography business when clouds gathered on the horizon, and the battles of Ayntab [siege of Ayntab] began” [62]. We don’t know if they were able to actually open a studio, or if they practiced without a physical studio, but we know that, in 1920, during the days of the siege, according to his own words, Dikran “succeeded in taking about 100 photographs of the battle, putting myself at great risk and under extremely dangerous circumstances” [63]. He photographed both fighters and their positions, and these photographs remain the living witnesses that immortalize the eight-month battle for Ayntab.

Later, Chakmakdjian donated some of the 100 photographs he had taken during the battle to Kevork Bedoyan, and the others to the authors of the book Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots [History of the Armenians of Ayntab], in which many of them were printed.

Chakmadkjian released a monograph entitled Ayntabi Hayots Ngarichner [Armenian Painters of Ayntab], in which he included his own biography [64], and from which we have obtained much of the information presented above.

The actions of the Chakmakdjian brothers during the siege of Ayntab created quite a stir at the time. In the early days of the siege, on April 23, 1920, Armenian officers detained the Chakmakdjian brothers for a short time. Dikran was taken to the police station, because out of concern for security and by the decision of the military council, photographing fighters and military positions was forbidden, and Dikran had violated this order. At the time, nobody knew what the outcome of the battle would be, and whether those photographs would incriminate the men appearing in them.

As arranged by Tatoul Kupelian, an advising member of the military council, Chakmakdjian was provisionally sent to the military police station. Later, another community leader, Kevork Baboyan, arrived at the station and demanded that Chakmakdjian be released. In response, Adour Levonian, member of the military committee, arrived on the scene, explained to Baboyan why photography was not allowed, and threatened to throw him “into the hole,” too, if he persisted in his demands [65].

The issue was complicated by party affiliations, as Chakmakdjian and Baboyan were members of the Hunchak Party, while Tatoul and his friends were members of the Dashnak Party [66], and Baboyan believed that party rivalries had played a role in the whole sequence of events.

The issue was resolved when Kupelian, in order to avoid a “cockfight” and for the sake of harmony, resigned from his position on the military council.

It was this event that Mgrdich Araradian, member of the military council, mentioned in a conversation he had with Krikor Bogharian. When the latter asked if there had ever been internal dissent among the members of the military council, Araradian replied: “In the early stages of the siege, we weathered a “storm” caused by the Chakmadkjian brothers, the photographers. They took photos of the fighters and the positions. They were caught, and some argued they should be allowed to proceed, but those opposed outnumbered them, so the council did not permit them to photograph” [67].

After the fall of Ayntab, Dikran Chakmakdjian settled down in Beirut and worked alongside his brother Kourken in the city’s office of public construction. Thanks to his position, he played an important role in the delineation of the lot on which the Saint Nishan Chuch is stands [68]. In 1922, he proceeded to Cairo, after which he and his wife emigrated permanently to the United States and settled down in New York, later moving to Englewood, New Jersey. For some time, he was a carpet merchant, but eventually he dedicated himself to painting, producing many works, seven of which were gifted to the Holy Cross Church (New York).

He also painted a portrait of the late U.S. President John Kennedy, which he gifted to Kennedy’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, receiving a note of gratitude in return. He painted a portrait of Catholicos Vazken I, which he gifted to him in 1961.

His works spanned multiple genres. Aside from Armenian, he also produced works in the Indian, Chinese, Persian, and Japanese style. He was featured in several exhibits. In the United States, he was an active member of the Union of Ayntab Armenians and served on its executive board.

He died of a heart attack on December 3, 1964 [70].

17. Kourken Sebouh Chakmakdjian

He was born in Ayntab. After the Armistice following World War I, he returned to Ayntab from exile, and alongside his brother, established a photography practice [71].

After the fall of Ayntab, he settled down in Beirut alongside his brother, and worked as an engraver and photographer, collaborating with S. Tashdjian. He died in Beirut, while waiting for the official permit to depart for the United States [72].

In Ayntab, he always worked alongside Dikran, his brother. In order to avoid duplication of information, we have not provided a separate biography for Dikran.

18. Salim Hatkayan

He is mentioned in Engin Özendes’s list of Ayntab photographers [73]. However, we have not encountered a photographer of this name in our other sources, and given the inaccuracies of Engin Özendes’s list, as well as the implausible and alien nature of the surname Hatkayan, we include this name in this article with some reservations. We wonder if Özendes misidentified another photographer who practiced for many years in Aleppo, Salim Khandjian.

- [1] Engin Özendes, Photography in the Ottoman Empire 1839-1923, Yem Yayın, Istanbul, 2013.

- [2] “Eskı Gazıantep fotoğrafları sergısı,” 2007, 36 pages.

- [3] Printed in Yerevan, in 2007, 448 pages.

- [4] Published by the Ayntab Armenian Union of America, United States of America. Printed in Los Angeles, California, 1953, volume A, page XXXII (1,088 pages); volume B, page XXXII (806 pages).

- [5] Published by the Ayntab Compatriotic Union.

- [6] The Very Reverend Garabed B. Adanalian, Houshartsan Hay Avederanaganats yev Avederanagan Yegeghetsvo [Memorial to Armenian Evangelicals and the Evangelical Church], Fresno, 1952, page 323.

- [7] “Cilicia. Attempt at Describing the Geography of Modern Cilicia,” Araks Series, San Petersburg, I. Lieberman Printing House, 1894, page 360; Kevork Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots [History of the Armenians of Ayntab], Volume A, Los Angeles, 1953, page 512, 847, and 850; his brother’s Mihran’s two deeds for the photographic studio.

- [8] “Historical Letter to Hovhannes H. Halladjian…” [an autobiographical letter], Hai Ayntab [Armenian Ayntab], Beirut, Year 7, 1966, number 1 (21), pp. 21-22.

- [9] The Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography in Ayntab,” Kevork Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume B, Los Angeles, 1953, pp. 292-293.

- [10] Ibid., page 293.

- [11] Ibid.; also Eli Nazarian, “City of Aleppo, rising – Armenian Master Photographers,” Zartonk [Awakening], Beirut, year 38, number 92 (14.265), January 18, 1985, pages 2 and 4.

- [12] The Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography…,” page 293.

- [13] Krikor H. Kalousdian, Marash gam Kermanig yev Heros Zeytoun [Marash or Kermanig and Heroic Zeytoun], New York, 1934, page 284.

- [14] Very Reverend Hampartsoum H. Ashdjian, Adanayi Yegherne yev Konyayi Housher(Badmoutyan Hamar) [The Massacre of Adana and Memories of Konya (For Posterity)], New York, Gochnag Press, 1950, page 202.

- [15] Krikor Bogharian, Ayntabagank, Volume B, Mahartsan, Beirut, Atlas Press, 1974 (the cover is marked 1975), page 43.

- [16] “Historical Letter to Hovhannes H. Halladjian…,” page 22.

- [17] Very Reverend Samuel Halladjian, “Reverend Haroutyun Halladjian and the Halladjian Orphanage,” Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume B, pp. 607-609.

- [18] Kermanig, Boston, 55th year, January-June 1986, number 219-220, page 24.

- [19] Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography…”, page 293.

- [20] For more information on him, see Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography…,” page 293.

- [21] Very Reverend Garabed B. Adanalian, Houshartsan Hay Avedaranaganats…, page 325.

- [22] Setrag G. Matosian, Ayntabi Krisdosasirats Ungeroutyun, 1896-1935 [The Krisdosasirats Society of Ayntab, 1896-1935], Aleppo, 1935, page 19.

- [23] Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume A, pp. 487-488 and 892.

- [24] Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography…,” page 293.

- [25] Sarkis Balabanian (Balaban Khodja), Gyankis Dak ou Bagh Orere, Ayntab-Kesab-Haleb [The Hot and Tepid Days of my Life, Ayntab-Kesab-Aleppo], edited by Dr. Toros Toranian, Aleppo, Orient Press, 1983, page 66.

- [26] Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography…,” page 293.

- [27] Puzant Yeghiayan (editor), Adanayi Hayots Badmoutyun [The History of the Armenians of Adana], Antilias, Printing House of the Holy See of Cilicia, published by the Adana Compatriotic Union, 1970, page 716.

- [28] Father Karekin Bogharian, “The Church of Ayntab…”, Hay Ayntab, Beirut, Year 8, number 4 (28), 1967, page 16.

- [29] Very Reverend A. Halladjian, “The Art of Photography…,” page 293.

- [30] For his biography, see Krikor Bogharian, Ayntabagank, Volume B, “Mahartsan,” pp. 173-175; Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume A, pp. 705-706.

- [31] “Report on the Situation of the Armenian Community in Baghdad,” Azk, Boston, year 11, number 145-919, June 28, 1917, page 2 and numbers 148-922.

- [32] Bulletin of Central Turkey College at Ayntab, 1909, pp. 17-33.

- [33] Archives of Arsen Yarman, July 2000, number 609, pp. 16-25.

- [34] Hisatak 1865/1930, Oemme Edizioni, Milano, 1990, p. 111; Jumhiriyah [Republic], Baghdad, June 5, 1999, page 8. [in Arabic]

- [35] Yeghia A. Kasouni, “History of the Central Turkey College of Ayntab,” Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume A, page 847.

- [36] Bulletin of Central Turkey College at Ayntab, 1909, page 23.

- [37] Krikor Bogharian, Ayntabagank, Volume A, page 22.

- [38] Lousavorich [Illuminator] Bimonthly Religious Review, Chicago, Year C, number 4, May 30, 1919, pp. 13-14.

- [39] Kersam Aharonian, Houshamadyan Medz Yegherni [Chronicle of the Great Genocide], Beirut, 1965, page 98 and 100.

- [40] Ümıt Kurt, "Bırecık'te ermenı sürgünlerını ölümden kurtaran Cemıl (Bahrı) Köhne", Toplumsal tarıh, no. 253, ocak 2015, s. 87

- [41] Krikor Sudjian, Gyankis Koghkotan (Housher Medz Yeghernen) [The Calvary of My Life (Memoirs of the Great Genocide)], dictated to Beatrice Khachadourian, Beirut, Kardashian Press, 1986, pp. 19-20.

- [42] Ibid., pages 21-23.

- [43] Hay Ayntab, Beirut, 9, 1968, number 3 (31), page 42.

- [44] Bogharian, Ayntabagank, Volume A, page 71; ibid., Volume B, pp. 600-602.

- [45] Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume B, page 293.

- [46] Executive board of the Aleppo Armenian Prelacy, volume 65 of minutes of meetings of the religious council, “Minutes of the Year 1913,” page 305.

- [47] Ibid., also, collection 9 of outgoing correspondence, page 264.

- [48] Armenian National Archive, Fund 425 (Father Mgrdich Bodourian, handwritten portion of Armenian Encyclopedia), list 1, work 108, sheet 85. The source also includes his and his daughter’s photograph.

- [49] Dikran Chakmakdjian, “Armenian Painters of Ayntab,” Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume B, pp. 732-733. Also see Volume A of the same work, page 850.

- [50] Dikran Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanknerou Veragochoum [Remembrances of Amida’s Echoes], Volume B, Weehawken, New Jersey, 1953, page 342.

- [51] Bulletin of Central Turkey College at Ayntab, 1909, page 31.

- [52] Mgount, Amidayi Artsakanknerou…, page 342 and 354; Tovmas K. Mgrdichian, Dikranagerdi Nahanki Chartere yev Kurderou Kazanoutyunnere (Aganadesi Badmoutyun) [The Massacres of the Dikranagerd Province and the Atrocities Committed by the Kurds (an Eyewitness Testimony)], Krikor Djihanian Printing House, Cairo, 1919, page 96; Arev [Sun], Alexandria, Year B, number 129 (285), March 9, 1917, page 2.

- [53] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of Armenian Clergy and its Flock's Catastrophic Year of 1915], edited by Ara Kalaydjian, New York, 1985, page 259.

- [54] Mgrdichian, Dikranagerdi Nahanki…, page 107.

- [55] Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume A, page 733.

- [56] Shrchanavardk Vartanian Grtarani Ayntab [Graduates of the Vartanian Institute of Ayntab], Ayntab, T. P. College Press, 1914, page 10.

- [57] Khoren Tavitian, Gyankis Kirke [The Book of My Life], Beirut, Shirag Press, 1967, page 292.

- [58] Ibid., page 408.

- [59] Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume A, page 851.

- [60] Chakmakdjian, “Armenian Painters of Ayntab,” pp. 734-735.

- [61] Krikor Bogharian, Tseghasban Tourke: Vgayoutyunner Kaghvadz Hrashkov Prgvadznerou Zrouytsneren [The Genocidal Turk: Testimonials from Conversations of Those Who Survived Miraculously], Beirut, Shirag Press, 1973, pages 169 and 178.

- [62] K. B. [Krikor Bogharian], “Dikran Chakmakdjian (1894-1964),” Hay Ayntab, Beirut, Year 6, 1965, number 1 (17), page 69; Sisag Varjabedian, Hayere Lipanani Mech [The Armenians in Lebanon], Volume A, Beirut, 1982, page 375.

- [63] Chakmakdjian, “Armenian Painters of Ayntab,” pp. 734-735.

- [64] Sarafian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, Volume B, pp. 732-735.

- [65] Kevork H. Barsoumian, Badmoutyun Ayntabi H. H. Tashnagtsoutyan 1898-1922 [History of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation in Ayntab, 1898-1922], Aleppo, Dikris Press, 1957, page 234.

- [66] Ibid., page 34.

- [67] K. B. [Krikor Bogharian], “Conversation with Mr. Mgrdich Araradian,” Hay Ayntab [Armenian Ayntab], Beirut, Year XI, number 39-40, 1970, page 101.

- [68] Sisag Varjabedian, Hayere Lipanani Mech, Second Edition, Volume A, Beirut, 1982, page 375.

- [69] Hay Ayntab, Year E, 1964, volume 3 (15), Beirut, pp. 59-61.

- [70] Hayasdani Gochnag [Clarion of Armenia], New York, 65th year, number 1, January 1965, page 26.

- [71] Chakmakdjian, “Armenian Painters of Ayntab,” page 734.

- [72] K. B. [Krikor Bogharian], “Dikran Chakmakdjian (1894-1964)”, page 70.

- [73] Özendes, “Photography in the…”, page 65.