Sandjak of Marash - Trades

Author: Varty Keshishian, 22 Sept. 2011 (Last modified 22 Sept. 2011) - Translator: Ara Melkonian

Marash has been known from the most ancient times as a flourishing centre for arts and trades, where the Armenian presence has always been felt. Thanks to the creative talent of the Armenian element of the population, certain trades have been developed to a very high degree from olden times.

Comprehensive study of the population’s occupations shows that a clear division of work exists there. Thus weaving, tailoring, dying, shoemaking, furniture-making, goldsmiths, watermills etc are Armenian trades while tanning, metalworking and tack-making are Turkish ones. [1] Trades are carried on in both city and village areas. Although the overwhelming majority of the province’s population is concerned with sheep farming and agriculture, there are large groups of villages and districts that display significant advances in the development of various trades.

One of the more developed regions is the purely Armenian-populated village of Fendedjak, the main and largest Armenian village in the Marash area, that with Dereköy and Kishifli form a village group. All the main trades and artisans necessary for life and living – weavers, shoemakers, carpenters, metalworkers, masons and bricklayers, millers etc are to be found here. They not only satisfy local needs, but also those all the surrounding Turkish villages which are totally bereft of trades. The population of the villages is occupied, apart from farming and animal husbandry, with producing timber, cutting trees from the surrounding forests and preparing beams, joists, roof timbers and other wooden items and, after satisfying local needs, exporting great quantities to Marash, Ayntab and nearby cities and towns. The establishment of the Bagdadbahn (Berlin-to-Baghdad Railway) at the beginning of the 20th century has been a great boon for this trade. The mill belonging to Manug Agha Kalusdian near the village of Kishifli provides for all the surrounding villages.

Just as for the whole province, the villages in the Anderen (Andırın) district to the west of Marash are famous beyond its borders for the manufacture of carpets and certain forms of women’s clothing (called gaba), as is the high quality worked silverware made in the small town of Göksun, mainly by Circassians who have settled there, having brought the trade with them from the Caucasus. The mixed villages of Göksun, Deirmen-Dere (Değirmendere) and Tash-Oluk (Taşoluk) and the Armenian-populated villages of Kiredj (Kireçköy) and Geol-Punar (Gölpinar) are remembered as having only a few artisans – metalworkers and tinners, as well as grocers. Villagers generally go to the market in Marash for the important items they want. At the beginning of the 20th century, sericulture, as a source of profit, has begun to attract attention, and great mulberry groves have been planted around Marash to encourage the silk trade. But sericulture too, like many, many other trades, has stopped with the deportation and disappearance of the Armenian element of the population from Marash, because the local Turks have not mastered its methods and customs.

The town of Marash is incomparably rich in its variety and mass of trades. The environment and living conditions have naturally determined the kinds of trades that are followed and their development over time. During the 18th and 19th centuries Marash had already lost its importance on the various trade routes and therefore it’s centuries-old economic prosperity, and was restricted mainly to trades relating to living - and generally distant from richness and opulence.

It is difficult to provide answers to questions regarding when and under what circumstances this or that trade has developed in Marash. But the nature of work carried on, emphasised by certain unique qualities, descriptions etc, permit us to attribute them mainly to the Armenian element of the population.

It is easy, between the different Armenian ethnographic areas and industry in Marash, to see both generalisations and similarities. This is something that will assist us in understanding how the various trades blossomed in Marash. It is possible to conclude that Armenians who moved to this region in ancient times have brought with them habits, customs, and perceptions that traditionally – handed down from generation to generation and protected – have persisted. It is natural that trades too have, in this way, continued and survived.

Of course, it is inevitable that there have been influences and changes; certainly many things have been lost or forgotten. Today, it is almost impossible to answer questions as to what the changes to Armenian material culture in Marash have been, or under what influences has it grown rich. Of course, community, religious and social barriers have had a determining role in the pure preservation of some kinds of handicrafts. It should not be forgotten that certain trades are directly linked to making clothes, to life and living and to religious beliefs and perceptions. So it is possible to say that on the one hand community and religious customs, and pronounced Armenian traditions on the other, have preserved the continuity and subsequent development of trades in Marash.

By the second half of the 19th century, increasing new trade relationships and the advancement of science and engineering in the Ottoman Empire have given great impetus to trades, forcing the development of trade and industry on a local basis. Economic improvement and expansion of trade have created favourable circumstances for cottage industries to transfer to new fields of production – the foundation of factories and workshops – thus increasing production.

According to the data produced in the 1890s, Marash had 1900 shops, 7 caravansaries, 11 bath houses, 281 workshops, 2 factories producing soap in a domestic situation and 11 bakeries. [2]

At first glance these figures may really be considered to be exaggerated, or the population to be of a larger town, but it is necessary to point out that the establishments defined as ‘factory’, ‘shop’ or ‘workshop’ in reality are very small enterprises. For example, a place where a master craftsman and more than one worker worked is called a ‘factory’; the word ‘shop’, a generally understood term, might be understood as a tradesman’s workplace – where he works or sells goods. ‘Workshops’ are small workplaces, where the given trade’s artisans, members of his family and apprentices work.

Taking into account the Ottoman Empire’s standards, it is possible to say that the province of Marash has a quite a flourishing trading and economic state. Production satisfies the province’s population’s needs, and some trades produce enough even to export.

It is possible to divide the trades in Marash and the surrounding area into the following four groups

- Food – watermills, baking, sweetmeat manufacture, butchery and so forth

- Clothing and shoes – tailoring and dressmaking, shoemaking, furrier

- Textiles and weaving etc – weaving, sewing, carpet making, sock making etc

- Living requirements – goldsmiths, ironworking, copper working, tin working, lumber working, dying, carpentry, pottery, saddle making and so on.

The Armenians are generally in leading positions in all these trades. [3]

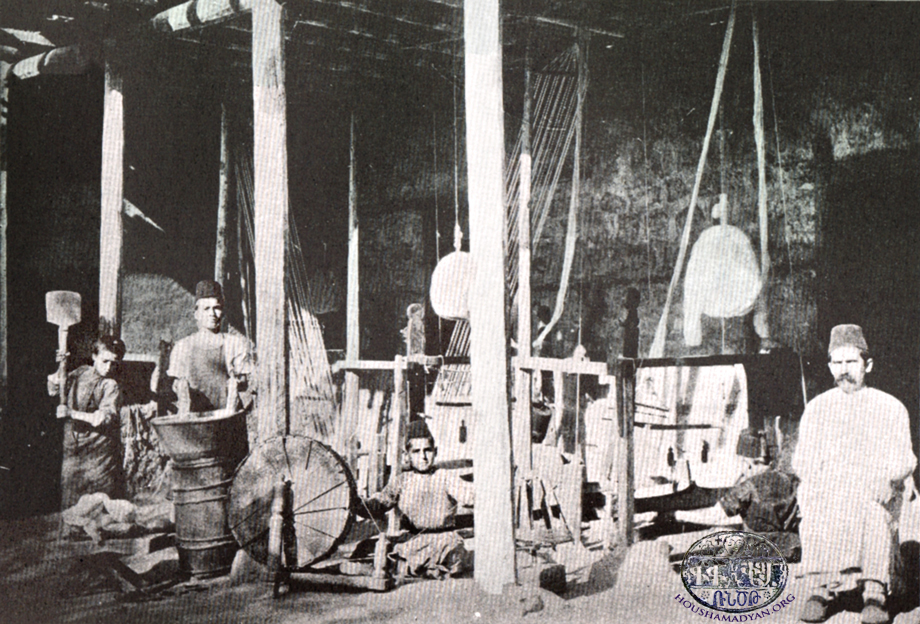

Weaving and textile making

This is the trade that uses the most hands in Marash and the surrounding region – weaving (djulfalik, djulhalik- çulhalık) – cloth weaving and its associated trades. Mainly in the hands of the Armenians, this traditional trade is the only means of earning a living for many families. It is as if the whole of Marash is a large weaving factory, where in each house – even the poorest – the loom (tezgah) and ‘pit’ are present. This means that weaving, the working of fabric, in the beginning, rather than a trade, has been a cottage industry, to provide the immediate necessities for the family with some extra for sale.

Towards the end of the 19th century, like all other trades, the production of textiles and cloth has seen a dramatic increase.

At the beginning there was no division of labour, in other words the work – from the cultivation of the raw material, the production of thread to weaving – was carried out by one person. By the middle of the 19th century, the rise in demand and volume has brought forward quite a wide network of ordering master craftsmen and trade workshops. Labour division has taken place, specialist trades have appeared – where thread weavers, dyers and weavers are each experts in their own fields.

Although this division is relative, and mainly concerns master craftsmen who own their own enterprises, the cottage industry method is still the main system in homes and villages. In reality, weaving is a popular trade and, handed down from generation to generation, continues to be an indissoluble part of living.

Weaving is carried on in both town and village environments; it is a ‘sought-after’ trade as much for men as for women. Perhaps it is because it is a trade that is carried out by both men and women that there are so many practitioners. To this must be added several other factors. First, the trade’s accessibility – in terms of manpower, raw materials and machinery, as well as the need and use of the finished product. No less important roles are played by the country’s engineering primitiveness and the limitations of the trades. It is Armenian enterprise that wants to utilise local means, to the greatest possible extent, for its immediate needs.

Thus weaving and all its associated trades are among the most developed and widespread in Marash and the surrounding area, each of which is one link in a complete chain.

The yarn, before reaching the weaving stage, has a long, laborious journey of cultivation to travel. First the cotton boll has to lose its seeds, then be wetted in a particular mixture of lapa, [4] then spread in the sun to whiten. Then it is washed with copious amounts of water in the river by being trodden, beaten with a mallet, then spread in the sun again. This work is mainly done by men.

The work of spinning thread using a bobbin or spindle is usually carried out by women. They spin yarn in different thicknesses: thick, thin and medium, each according to the cloth to be woven. The yarn prepared in Marash is much in demand by surrounding towns with little or no basic materials, where local demand is satisfied by importing yarn from Marash to make cloth. [5]

Thin yarn is used to weave the cloth called khasa (hasa or calico in English), which is much used generally both in Marash and other places. It is used to make women’s underclothes, nightwear, and especially for sewing of the necessary clothes to go into a girl’s dowry chest. It is also used as the material for embroidery.

Medium yarn is used for rough local cloth called bez or maghrum (mağrum) that is sold in great quantities in Marash and the surrounding villages. It is made mainly by women in their houses, who also prepare the yarn itself. It is used for beds and other household things, as well as the outer coats (entari) and baggy trousers (shalvar) worn by them.

Thick yarn is made into rough cloth used for the making of clothing worn by men: the coats called abay, yelek and zbun (zıbın) made from this material and dyed blue, and shalvars from that dyed black and so on.

Apart from cotton, other woollen material is used to make yarn – from sheep and locally bred goats – that after washing, carding and spinning achieve a new life. They are used for mens shalvars, coats called abay, etc.

Dying of yarn, treating it (khashel), [6] preparing bobbins for weaving shuttles (masura/makok or godj) and preparing warp threads for weaving are all carried out equally by both men and women. [7]

The comparatively thick woollen material produced in Marash called aladja (alaca) made of cotton or mixed fibres, a kind of dappled material, either striped or patterned, is very famous. It has got its name from its multicoloured, shaded, tinted or dappled colours. It is used to make both men and women’s long outer coats called entari or zbun (zıbın) that are used in many Armenian-inhabited areas. The aladja trade is mostly in Armenian hands. Apart from satisfying local needs, it is exported to all the towns and villages surrounding Marash, as far as Kayseri (Gesaria) and the interior provinces of Asia Minor, as well as Syria. [8]

It is significant that aladja (alaca), also known as manisa, is widely used not only in the towns and cities of Cilicia – Adana, Ayntab, Kilis, Hadjin and other places, but also in the Armenian provinces and places like Van, Kayseri (Gesaria), Istanbul, New Nakhichevan (near Rostov, Russia) etc. It is notable that the Marash aladja, with its characteristics of quality and colour, compares well with that produced in other Armenian-inhabited areas. This leads to the conclusion that, like many elements of Armenian handicrafts, the aladja tradition reached Marash centuries ago from the Armenian heartland through the movement of the Armenian highlanders and their retaining their skills from one generation to the next, maintaining its special characteristics. Thus, like weaving generally, the making of aladja belongs in the ranks of the Marash Armenians trades.

The trade is carried on by master craftsmen (alacacı ustası) who have tens, sometimes hundreds of weavers (çulha işçisi) working for them. The latter, taking the raw materials – great balls (yumak) of yarn (direz) – to their weaving sheds to make aladja cloth. The master craftsmen are, at the same time, the importers of yarn and the purveyors of the finished articles.

Many families have worked in the aladja trade in Marash before the First World War, among which are Bedros Yirikian and his family, Boghos Saatdjian, Vartivar Shahzadehian, the Bulghurdjians, Kovuklians, Der-Hovhannesians, Seferians, Medzabadivians, Der-Mesrobians, Hadji Partam, Garabed Hiusiukiutian and so on. These master craftsmen sold the aladja made by their workers in the alaca bedesdten (a market in Marash). [9]

Thus, during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, just as in many other Armenian provinces in the Armenian highlands, the most used material for making the basic kinds of clothing in Marash is the striped or patterned aladja cloth.

Despite the heavy and soul-destroying work, the workers making aladja cloth and weavers generally live in poor conditions, and with the low wages they receive hardly cover the needs of their often large families.

As to what essential role weaving has had in the life of the Armenians of Marash, it is possible to judge from the fact that even destans [10] dedicated to the trade have been created. According to oral information, weavers with particular skills create songs and destans in their work, the majority of which tell of the difficulties and hard work in the life of a weaver. Krikor Kalousdian, in 1899, when he was still a student in Tarsus College, spent his summer holiday working in the aladja trade, and has given the description of that trade and the weavers’ difficulties in a destan.

Here is an example:

Bizim esnafa denilir culfa,

Işçilerin de ünvanı ... kalfa,

Hazreti Ademin gününden kalma,

Bu sanatın adı büyükdür.

Of, şu dünyada var mı bir bela,

Ki çulfalıkdan beş-beter ola,

Şu nem çukarda düşmanım kala,

Yok, düşmana da derd büyükdür. [11]

The translation:

They call our fellow-workers weavers,

They call the labourers... kalfa [12]

A title that has remained since Adam’s time

This trade’s name is great.

Oh, is there a misfortune in this world

That is greater than being a weaver?

Let my enemy stay in this damp pit,

No, the pain is too much even for him. [13]

In his study presenting the educational efforts made in Marash, Harutiun Nashalian says that as well being young boys’ workplace, the weaving sheds also acted as schools. According to an old tradition, educated master craftsmen who knew literature, among whom were bothers and priests from Marash’s old monastic schools, first taught the young boys, in the workshops (çulfa damı), how to read a tahta: in other words they taught them how to read and write. The tahta is a square board, on which the alphabet is written and is hung round the children’s necks. After finishing the alphabet, they begin to learn the Book of Psalms, the Gospel, Nareg and others, while deacons who attended church learn canticles and chants by rote. [14] According to Krikor Kalusdian’s assurances, the weaving workshops in Marash have been the first schools for many clerics and intellectuals.

Apart from (alaca) there are other forms of textiles made. The abadji (abaci) workers produce abays and beden abays – the old-fashioned overcoats that are sometimes made of wool or silk and with the kind of decoration in gold thread called sirma and which are very expensive. There is also the outer sleeveless coat called boz abay that resembles a long Arab maşlah (cloak).

The material known as kumaş made of wool taken from goats or sheep is also widely used in Marash. There are a small number of master craftsmen who operate looms (tezgah) that, buying large quantities of wool from Turkish and Kurdish shepherds, having carded, spun and dyed it, make it into cloth. This woollen material is used to make men and women’s outer clothes – abays (coats) and shalvars (trousers). [15]

There are also belt makers (kuşakcı) who knit belts from wool and cotton – this form of long, wide belt is part of local costume and used as a sash wrapped around the waist several times. [16]

With the general spread of European cloth and clothes, textile production has gradually lessened, while certain kinds have disappeared from the market.

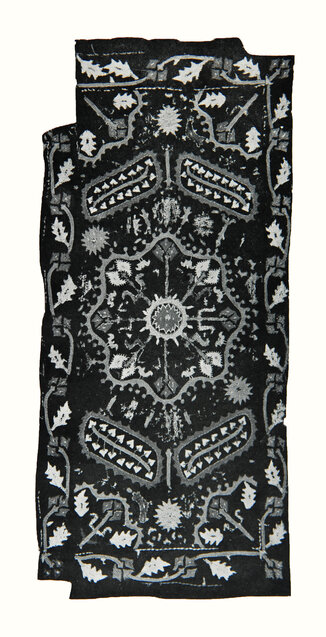

Embroidery

One important factor in Marash’s material culture is embroidery. From ancient times Marash has been famous for its rich tradition of textiles and embroidery. Many – mostly young - women and girls work in houses, and often in workshops, who embroider coloured patterns on manusas (coats) and mashlahs (cloaks) using gold thread and silver-threaded taffetas. Sewing and embroidery have never lacking in the traditional family houses in Marash; it is possible to say that they form part of their way of life. The embroidery that is known as Marash-work has become a compatriotic symbol, which today too is so familiar to Armenians from Marash.

Just like each town in Cilicia, Marash too has its style of embroidery called by the town’s name. The kind known as Marash embroidery is characterised not only by its individuality, but also by its uniqueness. Experts have difficulty reaching conclusions concerning its origin.

In the opinion of Serig Tavtian, an expert on Armenian embroidery, the external appearance of textiles from Marash is very similar to that of Ani, Old Djulfa and of Armenian lace-like sculpture generally. [17] In the embroidery produced in Marash the entire patterning contains in itself the elements often seen in Armenian carpets, miniature painting, architecture and decoration that demonstrate a cultural unity of the Armenian highlands. Just like the Armenian trades in Marash, embroidery too is descended from the sources of Armenian culture and has probably taken form from the combination of ethnographically different groups of Armenian embroidery. The embroidery of Marash is also unique in its development of patterns. Being handed down from generation to generation, it has retained, until today, its characteristics and completeness of pattern.

Marash embroidery has two separate branches; the first is the kind known as hartagar, and is worked using the Zeytun ‘handle needle’ (got asegh) way of sewing (the stitches are uneven, the pattern mainly covers the external side of the cloth, while on the other side only small stitches are to be seen). This method of sewing is also found in other provinces too, and is also known in Marash by the name of atlaslama. Worked on red or blue cloth in coloured thread into patterns, this traditional embroidery is bright and catches the eye and reminds one of patterned cloth. This form is used for bed covers, curtains, wall hangings etc.

The second kind is called kaghdnagar (secret sewing), a knitted form specific to Marash. It is somewhat complicated way of sewing, and the thread used is worked in a complex way that is only known to the embroiderer. It is probably for this reason that it hasn’t become widespread and is restricted mainly to Marash. This form of embroidery has not even spread to the Turks and Kurds of Marash. It is thought that it is the presence of crosses and cross shapes in the complex of patterns which has prevented them from becoming widespread. Each pattern has its own name and meaning – bardaklı (cup), çit-iğnesi (delicate needle), saatlı (clock), payamlı (almond), yedi dağ çiçeği (flower of seven mountains), fincanlı (cup), zambaklı (lily) and so on.

It is mainly worked on local blue or red dyed cotton cloth of the kind called khasa (hasa), using woollen, cotton, silk and occasionally gold threads that have been well spun. It is used on parts of clothing, curtains, table and bed covers, and on other things used in ordinary life, and sometimes on rich church vestments.

Apart from these forms of sewing, Armenian women of Marash are experts in almost all forms of Armenian embroidery, and are used to working silk, gold and pearl-decorated decorations. [18]

Apart from the master craftsmen who work in houses, there are embroidery workshops in Marash and shops with workshops in them. The master craftsmen obtain the cloth and thread and hand over the work to those working in houses. Marash embroidery is exported to both distant and nearby towns.

Girls generally learn how embroidery at home as well as in girls’ schools. In any event it is not surprising that, along with foreign languages and science, the girl students are taught embroidery.

Silk spinning

Silk spinning (kazezlik, spinning silk thread). This is regarded as a special Marash trade, and is mostly carried on by the Armenian element of the population. In Marash, especially at the beginning, sericulture wasn’t taken up, and silk thread and decorated spun wear was all imported, mostly from the commercial markets of Aleppo and Damascus. Silk textiles are very expensive, only the rich being able to afford them, so as the market for it are very limited in Marash it is not produced. In its place the silk spinning trade was developed. The silk tassels, edgings and spun tessellated decorations made by master craftsmen in Marash, more than being sold in the town, are exported even to very distant towns and cities, where they are greatly sought after. From the 1880s one of the master craftsmen, Chorbadji Hagop Agha, is remembered, who was a kazez (silk weaver) as was his son Deovlet Effendi Chorbadjian and his brother Tavit Chorbadjian. The latter has continued his trade for many years, and his sons Giragos and Nshan has also followed suit. Nshan was killed during the 1895 massacres, while his brother Giragos, who has followed the trade for many years has, thanks to his humanitarian merits and trade skills, earned the Turkish sarradj/sarac traders’ respect. His trade has been followed by his son Dikran Chorbadjian. Another kazez, Hadji Kasbar Geoniubeyazian, is also remembered. [19]

Carpet making

Until the end of the 19th century, despite the abundance of materials and great expertise in dying that was available, there was practically no carpet or rug making industry in the town. The production of carpets and rugs, which is mainly carried out in the province, has developed in the surrounding villages and is considered to be a Kurdish tribal monopoly. Great quantities of rugs and fewer carpets are woven and sold outside the area, bringing in an important profit. Those rugs, produced of high quality wool, the threads of which are dyed with dyes made from plants, are very famous in the surrounding towns.

Serious steps have been taken to produce carpets in Marash. The Shark Khali Kumpaniasi (Şark Halı Kumpanyası, The British-Eastern Carpet Company) was started in Marash in 1910 and, opening factories [20] encourages carpet making. This successful enterprise did not last long due to the deportation and massacre of the Armenian inhabitants of Marash and the surrounding area. A famous name in carpet production is Krikor Medzadurian. [21] Other merchants dealing with carpets that are remembered are Hovsep Dishchekenian and Sarkis Chorbadjian etc. [22]

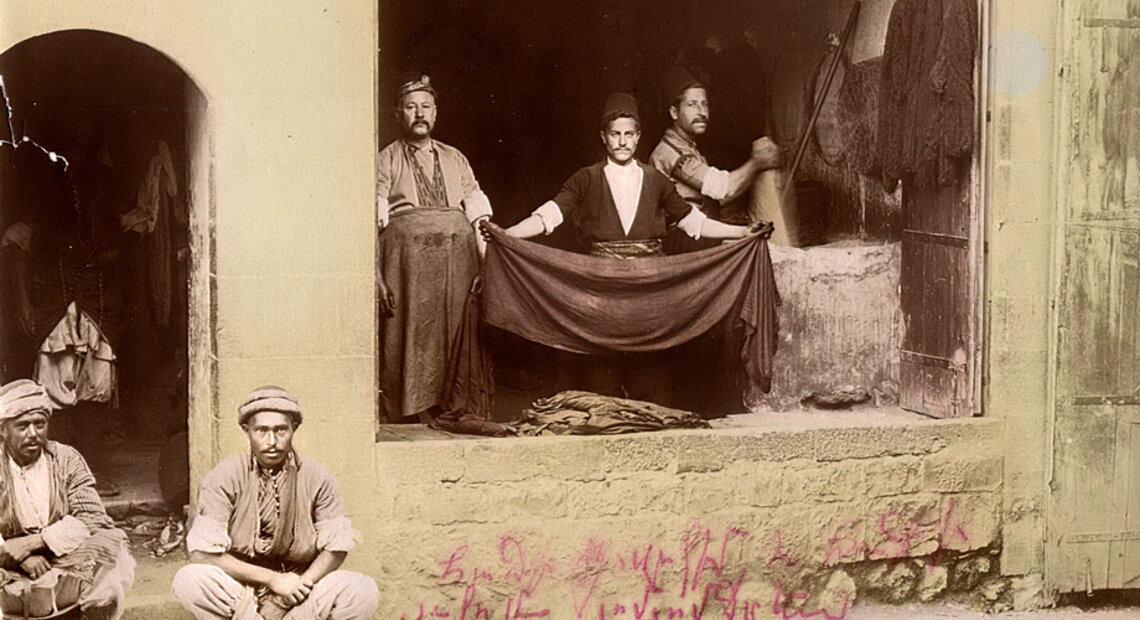

Dying

Dying is a unique trade in Marash, reaching quite a high standard thanks to Armenian master craftsmen. The development of textile production, carpet making and embroidery has been greatly determined by dying processes and especially by the quality of the dyes used. At the time when European yarn and dyed textiles were still not widely available, the Armenian dyers of Marash dyed cloth, yarn and wool in many shades and colours. After that, the textiles that have been produced in Marash – aladja and coloured cloth, carpets and other worked items – have held their own in competition with European production due to their unfading colours.

The Marash dyers have been famed beyond the region’s borders for many years. [23] They have dyed cloth, yarn and wool with plant, animal and mineral dyes and, from the middle of the 19th century, chemical dyes too. The Marash master craftsmen have mastered popular methods, thanks to which they have achieved colours that have not been supplanted by those of Europe.

The most important colours in Marash are the blue and red that originated in medieval times in Armenia, then golden yellow, milk-coloured (white), nut brown, mauve, black and all these colours’ various shades. Cloth is dyed blue in the traditional way, with indigo dyes (çivid boya), the indigo being imported from Europe, [24] the red is obtained from the root of the madder plant, and yellow from a yellow plant brought from Zeytun. [25]

Colour has important meanings and is not chosen at random; the cloths used for clothing or living had set colours. The colours and their combinations are also traditional, being passed down and retained in Marash’s textiles and life.

Just like clothing, so too items prepared for use in living are generally made of cloth dyed with a single colour, on to which delicately coloured sewn or printed patterns are added.

Of equal importance with the colour are the decorative patterns used – lines, dapples, trapezoidal, zigzag – each of these geometric or plant-shaped patterns has its name and meaning.

The dye masters in Marash are Hadji Artin Dadian, Khacher Chirishian, Mgrdich Dilenian, Lomlomdjian, Artin Alabashian etc. [26]

Printing - stamping

Printing on cloth (basma) is a quite well-developed trade in Marash that in the hands of the master craftsmen of the town has reached artistic standards. The printers (basmadji) use engraved blocks of wood to create the master of the pattern (kalıb) from which the cloth is printed.

Local production is called saghbazar/saǧbazar basmasi, the name being taken from the printing produced by the Saghbazarian clan of Marash. Krikor Kalusdian tells us that the printing dye, wooden master blocks and everything else used by this numerous family that lived close to the Boghaz-Kesen market were of their own making. Thus it is a trade that has traditionally been passed down from one generation to the next and has provably turned into a serious industry. The finished production is sold in both the town and the surrounding villages. [27]

The stamped cloth is used for church curtains and for the preparation of various kinds of cover. It is in widespread use, decorated with printed flowers, as the female headcovering or yazma.

One of this trade’s branches is that of yağlıkcı (handkerchief or scarf making) printing on to thin gauze or tulle material. This trade has been especially developed by the famous Hovhannes Chorbadjian, in the Kiumbed quarter, who prepares large printed handkerchiefs of gauze or tulle. He also made all his own printing gear and ancillaries. [28]

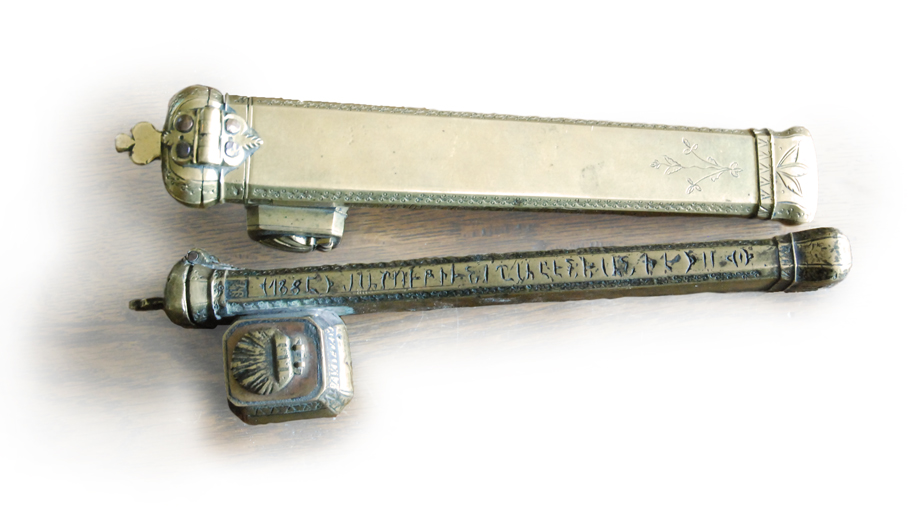

Goldsmiths

The working of gold is the oldest and most developed art in Marash and has reached a very high standard, mainly through the skills of local Armenian master craftsmen. Sources testify that skilled Armenian goldsmiths and jewellers have worked in Marash even as early as medieval times, leading us to suppose that working gold, silver and their associated jewellery creation were of quite a high standard even then. In 1710 the scribe, Rev. Sarkis, in the colophon of a Book of Days that he transcribed, writes with great praise of the Deacon Garabed Khodja, the person who commissioned and was the recipient of the transcription, saying that he was a merchant and an expert on jewels:

‘... Deacon Garabed was Godfearing and devout, an honourable and delicate man, blessed by God and praised by men ...who was a clever merchant dealing in noble pearls and jewels, as well as being a doctor who found noble medicine, and who thought deeply as to which country things came from.’ [29]

The goldsmiths of Marash, continuing the traditions of Armenian gold working, have developed this noble trade with new forms and styles. They have produced wonderful gold and silver ornaments – delicate women’s necklaces (gerdanlık), bracelets, belts, tiaras (pirpirim), caps, earrings, rings and decorative pins. They have also produced church ornaments and ceremonial items: mitres, staffs, buckles, crosses, chalices, censers etc as well. Armenian goldsmiths have skilfully adopted various methods and means of casting, encrusting, plating, filigree (with pairs of threads - çift) and engraving. Blackening (savat) on silver has also reached a high standard. The Marash goldsmiths’ creations were exported to all the richest towns and cities in the Ottoman Empire. [30]

Tailoring

The people of Marash and the surrounding area, until the middle of the 19th century, have always worn local forms of national dress, made either of wool or woollen materials, such as bükmeli fermane, sırmalı yelek, çuha şalvar and jüppe sako. The women wore female variations of some of these - sırmalı yelek, sako etc. Certain areas of some – the fermane, yelek and shalvar/şalvar - are decorated with gold thread. But they have gradually given way to European forms of dress. For this reason tailoring has divided stage by stage into two specialised branches – eastern and western. The eastern – the old form of tailoring, which in Istanbul and other places is known as Osmanli terzisi (Ottoman tailoring) has, very surprisingly, taken on the name bashibozuk (başıbozuk), meaning irregular soldiers. [31]

According to the information collected by Krikor Kalusdian, the European form of tailoring was introduced into Marash by a Greek master tailor and an Armenian named Halebli Artin Usda. Contemporaries are also recalled: the Sogradian brothers and Serop Usda Kupelian who learnt tailoring in Aleppo and returned to Marash. He was able to reach a leading position among his fellow tailors in a very short time, also satisfying the requirements of government officials. People began to relinquish the fermane and abay in favour of European coats and clothes. Serop Usda was awarded a Certificate of Merit in the International Exhibition in Paris, France, in 1905. He taught tailoring to more than 60 apprentices. The tailors Hagop Nuskhedjian (a native of Sis, who settled in Marash), Mihran Varjabedian, Bali Balian, Boghos Kardjeian, Manug Bilezikdjian, Nerses and Apraham Asdardjian etc are all remembered. [32]

Shoemaking

Like tailoring, shoemaking is divided into two branches – eastern and European. Those shoe makers producing European shoes are called kunduracı, all of whom are Armenians. It is remembered that at the beginning the shoes they produced were rough, but they have gradually become finer, becoming almost like shoes from Europe. It is notable that at the beginning of the 20th century Armenian shoemakers, to perfect their trade, have often visited Europe and Europeanised towns and cities. Shoes are made of tanned and dyed goatskin, mostly to order. Naturally, in the absence of industry and only having a limited market, there is no large-scale production, so the number of shoemakers producing European-style shoes is not very large. [33]

The eastern kind of shoe called yemeni are used in summer, young people wearing red ones and older people black. During the winter the kind of shoe called edik is worn. This is mostly worn by the peasantry and the Turks. There is also the kind of footwear called postal which is laced up, worn by some peasants and townspeople of the more affluent class when they travel, and is the forerunner of the boot. Sandals called çarık are worn in the villages. The cobblers who make the eastern kind of footware are known as yemenci and edikçi. The yemencis also make women’s footwear called karçın, as well as the galoshes known as mest that are used in winter, generally by the Turks. All these kinds of shoes are made by both Armenian and Turkish cobblers; the Armenians specialise in European-style shoes, and the eastern kind by the Turks. They have their own particular market places, where they make and sell them.

There are also shopkeepers known as kafaf, who are retailers, buying shoes from the trades-people and selling them on at a small profit. [34]

Some of the craftsmen who make European-style shoes are Hovhannes Salibian, Baghdasar Zulalian, Hovhannes Getsoyian, Nshan Mumdjian, Khachov Balian, Garabed Djansezsian, Dikran Chinchinian, and so on. Local kinds of shoes are made by Boghos Atamian, Artin Chirishian, Boghos Sabendjian, Krikor Khanemian, Harutiun Cherkezian, Garabed Tekeyian and so forth. [35]

Tanning

Tanning, also known as dabbaghlik (tabaklık) is one of Marash’s oldest and most profitable trades and is a mainly Turkish one. To treat the hides that are to become leather, they are taken to the underground tanneries (tabakhane) on the south side of the river, near its flow. Here the local leather is prepared as is seg (thin morocco type leather made from goats or sheep’s hides). The hides are sourced from the town and local villages. The tanners of Marash dress the skins in traditional ways, and the trade has its own secrets. Dry leaves called tetrin are used to open up the hide, and a red wood called bakam is used to extract a dye to stain it red. Leather as such is made from large animal hides, and black, yellow or red seg from small ones. Marash’s güllü şeftali, a thin leather (seg) is noteworthy. At the beginning of the 20th century we find a few Armenian tanners who prepare leather in the modern European way. Hagop Shamlian and a tanner from Aleppo may be recalled. [36] The high quality leather produced in Marash, apart from satisfying local needs, is much exported to distant and nearby towns and cities. [37]

Tack making

This trade is very advanced among the Turks of Marash. The tack makers (sarradj/sarac) make very good leather saddles for horses, horse blankets, leather-bound saddlebags known as terki heybesis, reins, stirrups, weapon holsters, bandoliers, whips, belts and other fancy items, which they decorate with patterns made with gold and silver threads, silk tassels and edging. All these things are real examples of art, richly encrusted with sırma or sim – silver and gold thread decorations. The high level of workmanship may lead us to believe that the traditions of this trade are very ancient. The tack makers have their own special market in Marash called Sarradjhane (sarachane), where they sell their leather wares.

These leather goods that are called sarradjiye, are exported by Armenian merchants to all the major towns and cities of the Ottoman Empire. [38]

Furniture making (or cabinet making)

Furniture making (marangozluk) or, in Marash Turkish sandalyadjelik (sandalyeci) is a trade that belongs solely to the Armenians. Furniture making is regarded as a purely Marash trade that unlike other trades imported from outside, has been formed and developed in Marash itself. Vast forests around the Marash area and the plentiful supply of timber have had a large role in the development of the trade. These areas are rich in oak, walnut, chestnut and poplar trees. The forests, apart from providing plentiful supplies of kindling and lumber for building, also provide timber for the furniture making trade of Marash.

At the end of the 19th century there were more than 30 furniture shops belonging to Armenians in Marash. They produced furniture made of walnut and plane - beautiful chairs, tables, chests, sideboards and picture frames. [39]

The development of the furniture making trade in Marash has been greatly assisted by the foreign, especially American, missionary organisations that established themselves in Marash in the middle of the 19th century. The missionaries ordered the furniture for their organisations from Armenian furniture makers and, providing them with albums containing pictures of furniture in them as well as tools, were the driving force behind the trade’s development. [40]

Apart from satisfying the needs of the town, great quantities of furniture, packed in simple wooden cases, were exported to Adana and the northern provinces of Syria using muleteers, securing significant profits. [41]

With the westernisation of local customs, the use of European furniture was widespread in Marash, replacing the old kind of chair called iskemle and their cushions called minder.

Some of the Marash master furniture makers are Kevork Ananian, who was the master of the furniture makers trade the ustabaşı, the Alexanian family, Kevork Keshishian, Vartivar Santurian, the Naterians, etc. [42]

Stone masonry

There are no educated engineer-architects in Marash until the beginning of the 20th century. The preliminary plans for buildings were, before that time, prepared by experienced and proficient master craftsmen, who generally supervised construction too. Alongside those formerly built of wood or brick in the town are buildings built of stone which are increasing in number – churches, mosques, schools etc. Famous stone-built edifices are the multi-arched bazaars known as Bedisten, as well as the solidly-built bridges over the rivers and roads, all of which are the proof of the skills of the local master craftsmen.

Large modern buildings that affected the panoramic view of the town have been built by European and American missionary organisations since the middle of the 19th century. The majority are built by Armenian master masons and stonecutters. Among the master masons that are well known are the Kargodorians. Sarkis Kargodorian inherited the trade from his father and, developing it, becomes an expert architect. He was the architect of the famous Marash closed markets known as Eski Bedesten and Yeni Bedesten, the Tuz Khan, Khesher Khan and the Belediye Market, all of which are stone-built. He has successively renovated three bridges over the Aksu River and two over the Djihan/Ceyhan. He was also the architect-builder of the church of St Gregory the Illuminator in Yenidje Kale/Yenicekale, the Holy Mother of God church in Zeytun and the Marash church of St Kevork. He was the local government architect from 1912 until 1918. [43]

Famous Marash stonemasons are Bedros and Hovsep Zeytuntsian, Nshan and Hagop Vartoghlian, Apraham Gherdanian, Kevork Yemenidjian and so on. The number of people following this trade grown considerably towards the end and some of them, travelling round the villages in the Marash area, have built houses, churches and schools in them. There is a total lack of master craftsmen following this trade among the other local communities. [44]

Carpentry

Both Turks and Armenians take part in the carpentry trade (nacarlık). Separate from the furniture makers, the carpenters (nacar) construct the wooden parts of houses and buildings. With modern houses and buildings becoming widespread, the trade has become quite profitable. Certain items that are used in ordinary living are also made by carpenters. Among the Marash master carpenters Sarkis Mahramadjian and the Mangozlians etc may be recalled. [45]

There are Turkish woodworkers (çıkırıkcı) who make spindles or adze and other tool handles. With the development of furniture making, these tradesmen have also begun to make furniture parts with their primitive tools too, as well as beautiful ornaments made of olive or box wood. [46]

There is also a group of woodworkers, all Turks, known as küllekci, who make breadbins (ekmeklik), wine must containers, buckets, threshing rods and other wooden objects. [47]

Copper work

Copper work (kazancı, or cauldron maker) is a specifically Armenian trade which is quite well developed. Before glass and ceramics were common in Marash, copper vessels were generally used in houses. Coppersmiths, in their market known as Kazancı çarşışı, make every kind of copper vessel from sheets of copper imported from Europe – trays, cauldrons, large and small buckets, tubs, saucepans, strainers, ladles etc. This trade has been greatly developed thanks to the ability of the Marash Armenian coppersmiths. The copper items they produce are notable for their finish and artistic development. Apart from satisfying local needs, the things produced by hand by Marash coppersmiths are exported to nearby towns and cities. Notable Marash coppersmiths are Hagop Gabadian and his brothers, Avedis Kumruyian, the Haitayian family, Avedis Sandjian and his sons, the Saremenigians, the Senekdjanians etc. [48]

Apart from coppersmiths, copper smelters (külçeci) should also be mentioned, who melt down and hammer old and broken European copper vessels to make copper sheets to be re-used. Some of the copper smelters are the Senekdjians, Avedis Tokatlian and his sons, and especially the Gabadians. [49]

There are also copper smelting master craftsmen, known as dökmeci, among which are Asadur Deokmedjian and his sons Adur and Kevork, as well as the Yumshadjekians. [50]

Tinning

Tinning is a separate trade known in Turkish as kalaycılık that is widespread in Marash and the villages in the surrounding area. Master tinners (kalaycı) not only satisfy local requirements, but travel throughout Cilicia plying their trade.

To use reddish copper vessels and kitchen items safely after they have been made, they are tinned (kalaylamak) on the insides which then take on a silver appearance. It is the accepted practice to display tinned and shiny copperware plates on a dresser in the corner of the sitting room (sofa). Cleanliness-loving Armenian women regularly have the tinner re-tin and shine the house’s copper vessels and plates. [51]

Metalwork

Metalwork is a trade that is mostly Turkish; there are, however, some Armenian metalworkers. Before European metal items had begun to enter Marash, metalwork had held an important place in satisfying local needs and those of the surrounding towns and villages. In the main cast iron (külçe) from Zeytun and iron bars brought from Europe serve to make metal items. Household items like nails, locks etc have been made in Marash from ancient times, lately to be replaced by cheap European ones. But until the beginning of the 20th century there has been a great demand for items used in and around the home – tongs, skewers, hooks, trivets, knives, pruning knives, ploughshares, etc. There has also been a demand for items for the various trades – adzes, hammers, pincers, sickles, as well as horseshoes and nails to shoe horses with. The metalworking trades satisfy not only local needs but also those of the surrounding area and certain towns in the plains of Cilicia. Among those remembered in this trade are the Djehizian brothers, who being skilful smiths, were also armourers. [52]

Pottery

Several potters (bardakcı) work in Marash who make pottery using the local red clay to make vessels of various kinds – pitchers, pots, large water pots and so forth that are very widely used. These items potted from clay are then coated with a greenish substance which seals them and makes them watertight, giving the impression that they are made of coloured porcelain or china. Apart from these, pipes are also made, as well as half-round guttering for roofs. The Bardakdjians are potters in Marash. [53]

Milling

Just like in many areas, milling is one of the trades that are Armenian monopolies. Marash is renowned for its many abundant, fast-flowing streams, on which the town’s watermills are situated. There are up to 25 mills in Marash that mill the town’s cereals and cracked wheat (bulghur) into flour, mill sumach, clean rice etc.

It is well known that during unrest and massacres, the government has protected the Armenian millers, so as not to lack flour and bread. The Djinbashian, Kalaidjian, Djehdiyian, Piusiuikdjian and Balian families were all millers. [54]

Bakeries

Baking, which becomes one with owning a bakery (fırıncı), also is in the hands of the Armenians. There are two kinds of bakery – the first is kömbeci or simitci and the second ekmekci. The first bake cakes, ring biscuits, rolls, pastries (boğaça) etc, while the latter bake bread and oil cakes.

There is the custom in Marash of baking bread at home. That made at home is very, very thin and baked on a dome-shaped metal sheet called a sadj/sac over a fire; thus this kind is called sadj-bread. Two or three weeks-worth of bread is kept in special breadbins (ekmeklik) in the larder. It is important to say that making bread on a sadj is more usually associated with nomadic tribes and tribal groups that are continually on the move, while the Armenians as a sedentary people, have had always used ovens (tonir), which symbolise the ideal of being sedentary and tied to the land. This is pointed out as an example of the influence exerted by one ethnic group on another and the acceptance of a tradition different from their own.

The bakers Hampartsum Kalusdian, Minas Torian, Haladjian, Sazdjian and Meksekian etc are all to be recalled. [55]

Sesame oil production (mahsere)

In terms of nourishment, the production of sesame paste (tahin) and sesame oil (şırlağan) is a separate trade, the product being prepared in local oil presses or mahseres. Sesame paste and oil is much in demand, and used especially during the Lenten weeks. Of the people of Marash who practice this trade, Garabed Mahseredjian is to be remembered. Another press in the Seray altı quarter, is also operated by the Mahseredjian brothers. [56]

Butchery

Butchers (kasab) should also be included, as it is a trade that demands special skills. It is carried on by both Armenians and Turks. In Marash it is mostly mutton and goat’s meant that is used; various forms of salted meat (abukhd in Armenian) are prepared from the meat of cows and calves. Meat is always sold fresh. The meat prepared in the towns abattoirs is brought, on a daily basis by sallak (butcher's apprentice) to the butcher’s shop, where the butcher, in accordance with the rules of the trade, cuts up the carcass before selling the various joints and cuts etc. Butchers that are to be remembered are the Antosians, Charekians, Nalchadjians, Kaskasians, Arakelians, Karakashians, Burunsuzians, Yaghubians etc.

Soapmaking

Soap production is a quite advanced trade and mostly in Armenian hands. The first soap works (masbana) was founded by the partnership of Garabed Chorbadjian and Garabed Mahseredjian. There is also another soap works that belongs to Boghos Muradian. The soap works are small factories where work is carried on in a primitive way, but completely satisfy local needs, both in Marash and the surrounding villages. As there aren’t many opportunities to export soap, production is limited to providing enough for local consumption. [57]

Comb making

Comb making (tarakcılık) is a completely Armenian trade. Armenian craftsmen make combs for home use with on side coarse-toothed, the other fine, as well as single-sided small ones. Combs are made of boxwood (şimşir), a hard, yellowish wood that is much prized. Naturally it is not possible to produce large quantities by hand using primitive methods, but these combs have been used in Marash and the surrounding area until cheap European imports arrived, leading to the forgetting of this trade. The Mikilian family and a few others may be remembered as comb makers. [58]

Pack saddle making

Because there are no railways or roads suitable for wheeled traffic in Marash and the surrounding area, mules and horses are used as the mode of transport. This means that pack saddle making (semercilik) is a trade that is sought after. Both Turks and Armenians made pack saddles, a trade which is separate from that of tack making (sarac). Among those remembered in this trade are Harutiun Kantsabedian, the Pitirians and the Karaboyadjians. [59]

∗∗∗

Sources tell us of a number of other trades that were carried on in Marash, such as sock making, furriers, felt making (külâh - felt caps), and the craftsmen who traded in them.

The first photographer in Marash was Hovhannes Varjabedian. Because he took a photograph of Bishop Nigoghayos Tavitian (Khorkhoruni) of Fernuz/Fırnus armed and seated on a horse in 1888 and was accused of other things, he was imprisoned and taken to Aleppo where, with very great difficulty, he was freed. [60] Among the photographers that may be recalled are Hovhannes Halladjian (a well known photographer from Ayntab who often visited Marash and worked there) and Alexianos Uvezian. [61]

There are also watchmakers (saatçi); this term must be understood to mean watch repairers or sellers. The main watchmaker in Marash was Rev. Zakar Saatdjian, who was known in Turkish as the ‘watchmaker priest’ saatçikeşiş, who was killed in the 1895 massacres. Bedros Djernazian is also remembered in this trade. [62]

In Marash, just as in many of Armenian-populated areas of the Ottoman Empire, the majority of the trades carried on were family concerns, with the family taking the trade title as their surname, such as ‘boyadji’, ‘basmadji’, ‘aladjadji’, ‘bardakdji’, ‘kushakdji’ and so forth, from which Boyadjian, Basmadjian, Aladjadjian, Bardakdjian and Kushakdjian surnames were created. The names of trades are derived from Arabic and Turkish.

It should also be noted that Marash’s isolated position off trade routes and the restricted economic conditions sometimes forced many Armenians to imigrate, mostly to Adana, Tarsus, Aleppo and other places.

There is practically no information about the trade associations (esnaf) that have existed in Marash. Undoubtedly there have been in Marash, from ancient times, like in many Armenian highland and Cilician towns, detached trade associations created on an ethnic basis – esnafs, with all the master craftsmen and workers plying the same trade as members. There are a number of traditions concerning the existence of the esnafs – names which have been retained by groups of craftsmen, especially among the weavers. In essence, the relationship between master and apprentice, the trade hierarchy, the management of the training of apprentices and the titles ustabaşı, usta, kalfa and so on are the last remnants of those esnafs.

To write about the trades and their being plied in Marash and not make reference to the local orphanages and widows’ workshops is impossible. In 1894-1896, after the massacres that have taken place during the reign of Abdulhamid II, both Armenian and foreign organisations have begun the task of helping the many thousands of Armenian orphans and bereft, defenceless women and girls. Alongside relief and teaching, the American and European missionaries consider it of prime importance to make the orphans, women and girls self-sufficient and to prepare them for the future by teaching them trades. To this end they have founded factories adjacent to the orphanages, and widow-houses and workshops for the widows, where the orphans, widows and girls will earn enough to live on.

The finest master craftsmen have been invited to teach the orphans their trade. The basic trades taught are weaving, shoemaking, slipper making, carpentry, baking etc. Most of the girls occupy most of their time with embroidery and lace making.

In her memoirs, a long-serving Scots missionary Agnes Salmond who has served for many years in Marash’s Eben-Ezer British (later American) orphanage, tells that the worked cloth and the bread and pastries produced in the bakery adjoining the orphanage by grown orphans have good names among the people, while the grown orphan boys who have learnt shoe making have, in a short time, produced and repaired the shoes for all the orphans. [63] Boys who want to follow other trades have been sent to the best master craftsmen. In this way the majority have learnt a trade and, after leaving the orphanages, have found success in the world of work. Salmon speaks very highly of the lace produced by the girls and which has had great success in London, England, thus providing hundreds of widows and poor women and girls with work. [64]

The missionaries’ activities in helping orphans were very useful in developing and maintaining various trades.

- [1] Hovsep Der-Vartanian, The 1920 Marash massacre and a brief glance at the past, first Edition, Aleppo, ‘Arax’, 1927, Second Edition, ‘Arevelk’, Aleppo, 2010, page 46. (In Armenian)

- [2] T K Hagopian and others, Dictionary of place names in Armenia and adjoining regions, Vol 3, Yerevan, Publication of Yerevan University, page 722. (In Armenian)

- [3] The majority of the information concerning trades in Marash has been obtained from the book by Krikor Kalusdian, Marash or Kermanig and Heroic Zeytun, 2nd edition, New York, 1988, (in Armenian), as well as from other written and oral sources.

- [4] Lapa: a specially made solution used for improving and whitening cotton.

- [5] See H B Boghosian, General history of Hadjin, Los Angeles, 1942, page 171. (In Armenian)

- [6] Khashel: the action of wetting yarn in a special solution of flour and water.

- [7] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 284.

- [8] Ibid.

- [9] Ibid, page 286.

- [10] Destan: epic poem.

- [11] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 286.

- [12] Kalfa: master craftsman’s assistant.

- [13] Author’s translation.

- [14] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 429.

- [15] Hovsep Der-Vartanian, op. cit., page 66; Nazig Avakian, Armenian popular dress (19th to the beginning of the 20th century), Yerevan, Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR, 1983, page 14. (In Armenian)

- [16] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 290-291.

- [17] Serig Tavtian, Armenian Embroidery, Yerevan, published by Academy of Sciences, Armenian SSR, 1972, page 50. (In Armenian)

- [18] Examples of highly artistic Marash needlework or embroidery may be seen both in museums and in individuals’ collections. A rich collection of Marash needlework-embroidery is to be found in the Aleppo treasury – church robes with all their parts worked with gold, silver and silk threads, - armlets (or cuffs), censers, decorated bishops’ mitres, sash-like belts with pictures of the apostles embroidered on them, slippers decorated with gold, silver and silk threads, altar covers, silk chalice covers, linen curtains etc, that have come down to us as precious witnesses of Marash’s one-time needlework. A bishop’s cope made in Marash at the beginning of the 19th century, with gold thread decoration on light yellow silk has earned great praise from both Armenian and foreign experts.

- [19] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 292.

- [20] Carpet workshops must be understood.

- [21] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 291.

- [22] Ibid, page 306.

- [23] Archbishop Ardavast Surmeyian, in his History of the Aleppo Armenians, writes that dying and weaving were usual trades carried on by Armenians from Marash who had established themselves in Aleppo in ancient times. See: Archbishop Ardavast Surmeyian, History of the Aleppo Armenians, Vol 3, Paris, 1950, page 974. (In Armenian)

- [24] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 292.

- [25] Nazig Avakian, op. cit., page 14.

- [26] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 291-292.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] Catalogue of Armenian manuscripts of the church of the Forty Martyrs of Aleppo and belonging to others, compiled by Archbishop Ardavast Surmeyian, Vol 1, Jerusalem, 1935, page 153. (In Armenian)

- [30] The best witnesses to the Marash goldsmiths’ art are to be found kept in the treasury-museum next to the Armenian church of the Forty Innocents in Aleppo. Church items and ceremonial vessels belonging to the churches in Marash, saved thanks to great sacrifices and brought to Aleppo by refugee Marash Armenians who survived the genocide, are stored there. This collection, representing a very small part of the church ornaments, vessels and precious objects collected in the churches over the centuries – silver-gilt chalices, large and small crosses, pyxes, candlesticks and censers that once adorned the altars of Marash’s churches, today tell of the glories and richness of the past. This exceptional collection (about 40 pieces) represents an interesting field of study of artistic culture and different handicrafts of Marash. While they have become sample exhibits now, they were used in the churches of Marash and, from 1923 onwards first found their abode in the Holy Cross church in the Aleppo refugee camp that was founded by the efforts of the deported compatriots of Marash, but are now in the treasury there.

- [31] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 292.

- [32] Ibid, page 293.

- [33] Ibid, page 294.

- [34] Ibid.

- [35] Ibid.

- [36] Ibid, page 298.

- [37] Ibid, page 305.

- [38] Ibid, page 297.

- [39] Ibid, page 295.

- [40] Ibid.

- [41] It is well known that notable Armenian families in Aleppo often ordered the furniture for their homes from Marash furniture makers.

- [42] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 295.

- [43] Ibid, page 927.

- [44] Ibid, page 297.

- [45] Ibid, page 296.

- [46] Ibid.

- [47] Ibid.

- [48] Ibid, page 299.

- [49] Ibid.

- [50] Ibid.

- [51] Ibid, page 299.

- [52] Ibid, page 300.

- [53] Ibid, page 302-303.

- [54] Ibid, page 301.

- [55] Ibid, page 301-302.

- [56] Ibid, page 303.

- [57] Ibid, page 303.

- [58] Ibid, page 296.

- [59] Ibid, page 907.

- [60] Ibid, page 297.

- [61] See Mihran Minassian, Les photographes Arméniens d’Ayntab et de la Cilicie. Bref aperçu (to be published) (In French).

- [62] Kalusdian, op. cit., էջ 300.

- [63] Ibid, page 489.

- [64] Ibid.