Palu - Local history

HAVAV

In his book, Dikran Papazian writes the history of his village on many pages, the Ottoman portion of which begins in the 18th century. It is a history mixed with legends that obviously has included the village’s oral history that has been transmitted from one generation to the next, reaching the author. What is clearly seen in it is the beys’ dominant presence in this environment. It is interesting that Papazian uses the appellation ‘Turk’ rather than ‘Kurd’ that, at first sight might seem incorrect, but we think that he has used it knowingly. In other memorial books the word dadjig is used indiscriminately for all Muslim populations, be they Turkish, Kurdish or Arab. Thus we think that Papazian’s word ‘Turkish’ has a similar, general meaning.

Havav appears in this environment as a village full of Armenians that is also subject to the area’s Kurdish bey. The villager’s cultivable soil belongs to him and the village pays the tithe to the government. But in this history spanning several centuries we can see that at the same time Havav is struggling against the bey and his successors. The villagers try to stand against the bey’s increased oppression and his attempt to populate the village with Kurds that are loyal to him.

During these years this Armenian-populated village is ruled by influential Armenian meliks who often lead the struggle against the Kurdish bey. It would seem too that the village was a refuge for Armenians from other places. Some of the meliks were not natives of the village itself, but from those in neighbouring areas. In Papazian’s historic narrative successful rebellions are described where the defeated bey resigns from keeping his palace in the village, as well as the plan to settle Kurds in it. But he remains Havav’s bey and the villagers’ cultivable soil remains his. It is to be noted that every time that rebellions have succeeded, Havav has allied itself with neighbouring Kurdish villages. This might mean that in the system created by the beys there were fierce antagonisms, clashes of interests and competition. In these sorts of circumstances, a village like Havav might find people who are dissatisfied in Kurdish circles and ally itself with them with the object of standing against the bey’s arbitrariness. It is also interesting to note the position adopted by the local authority in thse clashes. They often stand with the villagers of Havav in their protests against their bey. This can mean that although the government allowed the existence of the beys’ rule in these areas, at the same time they tried to act as an obstacle to the the beys’ increase in power. Thus in this way a village like Havav would become a tool in the battles between the beys and the local authorities. The rebellions described below may better show these internal relationships.

Asli beg

The time in which this incident has taken place is not stated in the history. All that is clear is that it has happened before the 18th century. Havav at this time is part of the Ottoman Empire, and Asli beg owns this village’s cultivable land. This bey’s konak (palace) is located next to the village. The bey has tried to settle Kurds in this completely Armenian village, but melik Nazar and Rev Simon (the village married priest) lead the resistance to the bey and attempt to frustrate his efforts. The notable people of the Kurdish villages of Kejekan ally themselves with those of Havav. These Kurds are known to have maintained friendly links with the Armenians since ancient times. This clash ends with Asli beg’s konak being burnt down, making the Kurdish bey leave his seat. The local Ottoman authorities this time forbid Asli beg to rebuild his konak in Havav, something that is regarded as a victory by the people of the village.[1]

Hadji Tehad beg

This second event has happened in the 18th century. This time the bey ruling Havav is called Hadji Tehad beg, who succeeds in establishing his konak in the village. At the same time he tries to settle Kurds that are loyal to him there. It is said that to achieve his aims he utilises the Ottoman Empire’s instability, when the state is waging war on its external enemies. It is not certain which war was being referred to and noting the fact is of no real assistance in determining the approximate date of this incident. We only know that the most serious war in the 18th century was the Russo-Turkish war of 1768-1774. We can also assume that the local authorities have defended the population of Havav’s demand to keep the bey and and his faithful Kurds from the village.

In these years a great earthquake happened in Havav, resulting in the destruction of about half the village, including the bey’s konak. The villagers, led by melik Mardo, are against its rebuilding. They succeed in imposing their will and Hadji Tehad beg is forced to settle in Til village, four hours distant from Havav.

It is also related that in melik Mardo’s days almost all the villagers have swords and shields in their houses. It is also at this time that the sports of fencing and shieldplay begin. This form of jousting is one of the villagers’ favourite pastimes. Festivals of this kind have been held by the young people of the village, especially at weddings, right up until the end of the 19th century. In these years the villagers continue to maintain close relations with the inhabitants of Kejekan and Dersim that in fact have been their their allies against the bey.

How can such an alliance between Armenian Havav and Kurdish Kejekan be explained? Was it that these Kurdish villages too have suffered due to the beys’ power and can see that they are natural allies of Havav and its inhabitants in their struggle against this feudal system? Armenian sources generally explain the links with the villages in question with the supposition that their inhabitants were formerly Armenians. Such hypotheses, it must be said, have become topos in Armenian memorial books.

In these years melik Mardo and his people from Havav have become a notable force within the Palu beys’ system. It is said, for example, that their neighbouring Kurdish village of Saroudjan and their leader melik Lama have requested assistance from Havav when their village has been attacked by Slo beg of Djabaghchur. Melik Mardo, with armed men from both Havav and Kejekan hurries to their aid and captures Slo beg, who is only freed after paying a cash fine. Later Slo beg attacks Havav, having the backing of the village bey Hadji Tehad beg. But Havav doesn’t remain alone in this battle. The men of Sarudjan, led by melik Lama, as well as those from Dersim and Kejekan rush to Havav’s aid, and eventually defeat the aggressor and once more capture Slo beg.[2]

Sharif beg

A third incident took place in the middle of the 19th century. It is almost the same scenario: the Ottoman Empire is at war with Tsarist Russia, the local rulers are slack, the Kurdish bey of Havav, Sharif beg, sets up his konak in the village. Like his predecessors, this bey tries to settle Kurds loyal to him in the village. It is told that, with the object of creating dissention among the villagers, Sharif beg allows an Armenian Protestant badveli (preacher) to settle in the village to preach Protestantism. Resistance begins against the bey’s presence and the steps he’s taken, led by melik Chapkun (Simon Chapkunian) and Rev Toros Solklindj. They don’t question the fact that Sharif beg owns Havav’s cultivable land. But against this they do refuse to allow the bey’s horses to graze in the village’s gardens, as well as the villagers having to provide the bey with wood every autumn. The result is that Sharif beg forces the villagers to collect wood for him by using force – beating the villagers. At this the villagers grow angry, surround the konak and demand the bey’s final departure from the village. Meanwhile melik Chapkun, at the head of a delegation of Havav villagers, presents himself and the delegation to the vali (provincial governor) of Diyarbekir – to whom Palu is subject – and gives the vali a petition describing Sharif beg’s arbitrary acts. It is said that the vali shows benevolence towards the delegation, asking the villagers to bring a notable Kurd or Turk to him who will endorse their petition. It is not difficult to find someone. This time the delegation from Havav takes a Kejekan tribal leader, Hadji Bairakdar of Golarak village to Diyarbekir with them, so that he can state to the vali that Sharif beg’s presence is a scourge not only for Havav but for the all the villages of Kejekan.[3]

Armenian sources note that, as a result of this protest and on the vali’s initiative, the problem existing between Havav and Sharif beg reaches the Ottoman courts. This in itself is a rare occurrence in Ottoman reality. It is obvious that the people of Havav enjoy the vali’s backing, and therefore agree to go to court about the problem. We don’t know the exact date of this incident, but we suppose that it occurs between 1860 and 1870. In any event, the people of Havav mobilise their resources and prepare their case for the court. A collection of money is taken up in Havav with the object of defraying the court costs and even people from the village living in Istanbul join their compatriots with donations. It is said that the court case has lasted a whole year, first in Diyarbekir, then in Harput and finally in Istanbul. Dozens of people from the village give evidence.[4]

The result is the Istanbul court’s verdict that Sharif beg should be exiled to Tekir Dagh (Rodosto) and gives him 6 months to leave Havav. Later the severity of the sentence is lessened, so that agreement is reached that instead of Tekir Dagh, Sharif beg may move to Til village, which is about four hours distant from Havav.[5] At the beginning the region’s beys, aghas and tribal leaders have tried to back the bey and intercede with the Ottoman authorities so that they can nullify the court’s decision. But the vali of Diyarbekir, to whom the implementation of the verdict has been entrusted, remains immovable. He especially doesn’t want Sharif beg to increase the force at his command and wants to somewhat ease his position. At the same time the Kurdish bey in his turn shows signs of rebellion: he becomes even more enraged and gives new impetus to his pressure on the people of Havav. But Havav applies once more for Dersim’s help. Hired armed men are brought from there, whose presence must frighten Sharif beg. The deadline set by the vali pasha is almost up. On the last day Sharif beg is absent from the village. All the Havav villagers, armed with torches, rifles, knives, axes or cudgels, come together in front of the bey’s konak. The bey’s family and servants are still inside. The villagers remove all the konak’s inhabitants from the village by force, and then completely demolish it. The villagers celebrate this event on the same evening with a huge banquet, with the important people from Kejekan and Sarudjan present.[6]

Sharif beg, however, hadn’t said his last word. The massacres of 1895 and the subsequent destruction of Palu have given him the opportunity to re-establish himself in Havav village. Immediately after these bloody incidents, the people of Havav have begun work with the object of rebuilding their village. In these difficult circumstances, Sharif beg, through his gulams, continues his acts of robbery and looting, keeping the people of Havav under pressure. This is nothing less than blackmail, the idea being that he’d get permission to rebuild his palace in the village. Upon the villagers’ request, the government has stationed a jandarma (policeman) in the village to prevent further robberies. The presence of this government official encourages the people of the village, who became bolder in their self-defence against the robbers. As for Sharif beg, it is true that he hasn’t succeed in rebuilding his konak in the village, but both he and his son Tefig beg had greater access to it.[7]

The Russo-Turkish war and the plan to establish an imperial granary in Havav

At this time, while the Russo-Turkish war has been continuing in the Caucasus, the mutasarrif of Ergani Maden has arrived in Palu district in September 1878 and has decided that an imperial granary should be established in Havav. The object of this step is to utilise the mills in the village and to stockpile flour and thus from this time onwards to supply the army stationed in Dersim. The Armenian prelate of Palu at this time, Rev Boghos Natanian, has tried to dissuade the mutasarrif pasha, arguing that the presence of soldiers in the village could give rise to various forms of violence against the villagers. It is known that the movement of the army through the district in the last few months has not left good memories for the people of Havav. The pasha isn’t persuaded; when he personally arrives in the village to make the necessary arrangements on the ground, he has been faced with protests against this step by the villagers who try to stop the building of the granary. It is only at this point that the pasha acquiesces and the granary is established elsewhere.[8]

Tefig beg

Sharif beg is succeeded by Tefig beg, who was also known under the names Taifur, Tefil or Tefo. Like his father he too has continued to remain in Til village, and the whole nahiye of Amshad is under his rule. It is during his time that the tillable fields have been divided between five of his relatives – later the number has been reduced to four – beys.[9] In 1908, when constitutional order has been established, an armed clash has taken place between, on one side, Tefig beg’s armed men and those of his allies forces and, on the other, those of Ibrahim beg of Sakrat and Rushdi beg. The reason for the incident is the question of the ownership of Giuliushger village. Despite Tefig beg’s call made before the clash to the villagers of Havav, the Armenians of the village have refused to take part in the battle. After the clash was over these three begs have been tried and convicted by the local courts and held in Ourfa prison for four years.[10]

The 1895 massacres

Just before the start of the massacre, a few people from Havav have already been made aware of its preparation. The fact is that they have been told by friendly Kurds and local officials.[11]

Havav has been surrounded on 22 October 1895 by armed Kurdish tribes and a mob from the neighbouring Kurdish villages. Armenian sources state that Captain Ali Effendi has had an important role in the success of this attack on Havav. Another active participant is the influential bey of Havav, Sharif beg, who has been trying to re-establish his credibility in the village. The people of Havav have immediately sent a delegation to neighbouring Sakrat village, the seat of the Kurd Ibrahim beg, and have asked him for protection, at the same time promising him a monetary gift. Ibrahim beg has promised to intercede with the local government on Havav’s behalf, but nothing useful has happened on the ground as a result of his efforts.

Havav is the richest Armenian village, so we can assume that large monetary bribes won’t change the Kurdish beys’ appetite very much. It is obvious that the outlook of looting and getting rich quickly, at the time when the local authorities themselves are encouraging them and every kind of violence is permitted, assuredly weighs more than anything else.[12]

It is obvious that the main object of the attacking mob is loot. The Armenians of Havav attempt to defend themselves, but we have the impression that there was more of a panic among the Armenians. The greatest feelings are of hopelessness and defencelessness among them all, and for this reason they begin to escape and disperse. A proportion of them have reached the nearby Kaghtserahayats Monastery, where the ordinary people have settled into its rooms while the men continue their defence. Others have found refuge in their Kurdish friends’ houses and especially in Armenian-populated Sakrat village that is under the Kurd Ibrahim beg’s protection. The number of Armenians escaping to Sakrat swiftly reaches 300-400. Among them are also unfortunate people from Tset, Shinaz, Abrank, Sgham and other villages. Mounted police arrive in the village a few days later, relocating the Armenians finding refuge there to the barracks near the town of Palu, and from there to the Armenian quarters of the town itself. Ibrahim beg and Rushdi beg and their armed followers have accompanied this Armenian caravan the whole way from the village as far as Palu, maintaining their protection. Thus the Armenian peasants that escaped the Havav massacre reach Palu, before the massacres began there. Many of them settle in the town’s St Greory the Illuminator church and others in the Protestant meeting hall. It is during these days that the attacks on the Armenian quarters of Palu have begun and people from Havav have also lost their lives in the violence. At the end, the repercussions of the violence have been very bad for this village of about 180 houses. Over 100 people from it have been killed and houses looted and burnt.[13] It is during these years that the ‘Deutscher Hilfsbund für Armenien’ missionary organisation is set up in the town of Palu, organising an orphanage where 80 boys and 70 girls have been looked after. It has lasted from 1894 to 1899.[14]

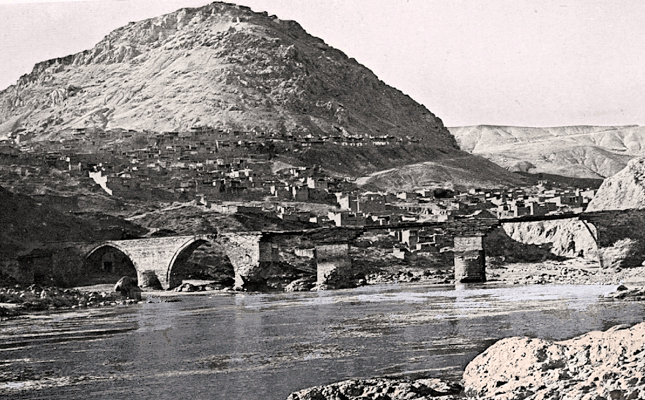

PALU (Town)

The 1895 massacre

The bloody events of 1895 have lasted for about three days, starting at the end of October. According to witness statemants the instigators have been local government bodies, who have given the town’s Turks three hours to attack the neighbouring Armenian quarters. At first the Armenians fortified and defended themselves in their quarters. Then, once more at the initiative of the government bodies, Zaza Kurdish armed groups, brought in from the surrounding villages, have invaded the town with great impetus and the massacre has begun.[15] About 1,000 Armenians have died during these events and almost all the houses have been looted. Girls have also been abducted. An example is given of a girl from the Chortoyian family who has been abducted by the Turks of the town. It hasn’t been possible to return her to her family after peace has been restored. 250 similar abductions have been recorded.[16]

Many Armenians have been able to find refuge in their Turkish acquaintances’ houses. This neighbourly defence has been salvation for many Armenians, as otherwise it is very probable that many more would have been killed by the invaders.[17]

OKHU

We don’t find much about the local history of Okhu in Parunag Topalian’s book. Here are the few facts gleaned from it.

The Russo-Turkish war (1877-1878)

During this time Ottoman army detachments have stopped and rested in Okhu for 3-4 days at a time. Many of the villagers have escapes from the village and have re-established themselves in nearby places. The Ottoman army has terrified everyone. Those who are left in the village organise themselves: all the young women and girls have been hidden in a house, and piles of wood arranged in front of its door. Food is taken to them secretly via the roof. It is obvious that the villagers are afraid of rapes being committed by the Ottoman soldiers. Several days later it has proved possible to secretly move the women out of the village to somewhere else.

Several months later the Ottoman army has once more passed through the village in a totally disorganised state. It has been defeated and escaping and wounded soldiers have appeared, all of them pale and in need of nourishment.[18]

The 1895 massacre

When irregular troops entered Okhou, many Armenians have sought shelter with their Kurdish friends (kirva). For example a group of Armenians have escaped to the neighbouring Sharoudjan village and Kurdish friends had taken them under their protection. The Armenians there have suffered three casualties. Apart from this, many houses have been looted and burnt; the village church and school have both been demolished. Incidents of abduction have also taken place, one of the protagonists being the village’s Kurdish mukhtar Meho.[19]

BAGHIN

The 1864 trial

This incident, that has achieved the status of an historical event, concerns the court case opened by the villagers of Baghin against their ruling Kurdish bey. This has been an unprecedented move of protest, the leader of which is Avedik Choloyian. He has been able to unify Baghin with regard to all the legal steps to be taken against the bey for the whole of the trial. The bey’s name is not recorded in the sources, but we know that the people of Baghin have taken up a collection and have brought together the sum of 200 gold Ottoman liras for the cost of the trial. Later, Avedik Choloyian has departed for Istanbul with the villagers’ protest letter. The trial between the people of Baghin and the bey who had taken over the village’s land has taken place in the Ottoman court which, according to Armenian sources, has ended with the villagers’ victory. From then on the villagers have become the legal owners of their land. According to the same sources the Kurdish begs have succeeded in gradually regaining their despotism in this village.[20]

The 1882 famine

This event has also left an important mark in the village’s collective memory. It has happened in the summer of 1882, when thousands of locusts have descended on the village’s fields and have ruined all the crops. It is the village’s entire winter crop that has unexpectedly been obliterated and the village is threatened with famine. It is known that the village has endured a terrible winter and has only emerged with difficulty from this natural disaster.[21]

The 1895 massacre

The village has only had a few victims during this time of mass violence. The majority of the people from Baghin have been able to find shelter in the neighbouring Kurdish villages. Often the Kurdish villagers, while playing host to the Armenians, have joined the attacks on Baghin, looting and burning certain houses and demolishing the village church of St. Sarkis.[22]

NERKHI

The 1895 massacre

Acts of violence begin in this village, that lies to the north and close to Palu (town), in the autumn of 1895, or more correctly, in October of this year. One morning the villagers find the village surrounded by many Turks and Kurds. The whole population finds refuge in their compatriot Boghos Effendi Bozian’s three storey stone house. Bozian is an official banker (sarraf) and, thanks to this position, a few gendarmes have arrived to protect him from the attacking mob. But their presence doesn’t last long. When the mob’s attacks centre on Bozian‘s house, the gendarmes immediately mount their horses and ride away, leaving the population of the village to its fate. The attackers smash the mansion’s gates and windows and force their way in. Acts of violence begin. 74 Armenians from this small village are killed.

The mob begins looting and, before withdrawing, sets fire to most of the village. Survivors of this massacre take refuge in nearby Sakrat village, which is the seat of the influential Ibrahim and Rushdi beys.

These bloody events leave deep scars on the relationship between the Armenian villagers and populations of places nearby. Boghos Melikian who records testimony about the village of Nerkhi points out that he was only one year old at the time of this incident, during which his father was killed with an axe. He also attributes the saying used by the villagers to quiet their crying infants ‘Keep quiet, the Turk will come’ to this massacre [23].

- [1] Dikran S. Papazian, History of Palu’s Havav village (in Armenian), Published by Mshag, Beirut, 1960, page 14-16.

- [2] Ibid., page 17-21.

- [3] Ibid., page 22-28. Harutiun Tsakhsurian, History of the valley of Palu from the earliest times until our days (in Armenian), Published by Donigian, 1974, Beirut, p. 388-389.

- [4] Papazian, op. cit., page 141-143.

- [5] Ibid., page 233.

- [6] Ibid., page 22-28.

- [7] Ibid., page 50-53.

- [8] Archpriest Rev Boghos Natanian, Tears of Armenia, or a report about Palu, Kharpert (Harput), Charsandjak, Djabagh Chur and Erzindjan (in Armenian), 1883, Istanbul, page 64-66.

- [9] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 411.

- [10] Ibid., page 415.

- [11] Papazian, op. cit., page 41.

- [12] Mesrob Grayian, Palu: Pictures, recollections, poetry and prose taken from the life of Palu (in Armenian), Published by the Catholicossate of Cilicia, 1965, Antilias, page 473-474.

- [13] Papazian, op. cit., page 45-49. Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 431. Grayian, op. cit., page 473-476.

- [14] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 405.

- [15] Grayian, op. cit., p. 469.

- [16] Ibid., p. 470. Tsakhsurian, op. cit., p. 268-269.

- [17] Grayian, op. cit., p. 470.

- [18] Parounag Topalian, Hayreni kyughs Okhou, Boston, p. 74-75.

- [19] Ibid., p. 76-78, 85.

- [20] History of the house of Baghin (in Armenian), published by the Baghin reconstruction and educational union, ‘Hairenik’ Press, Boston, 1966, page 125-128.

- [21] Ibid., page 128-131.

- [22] Ibid., page 131.

- [23] Boghos Melikian, Haireni Shunchov (in Armenian), Published by Hamazkayin, Beirut 1969, page 257-258.