Life in the region of Harput-Mamüretülaziz (1908-1915)

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 02/06/15 (Last modified: 02/06/15)- Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

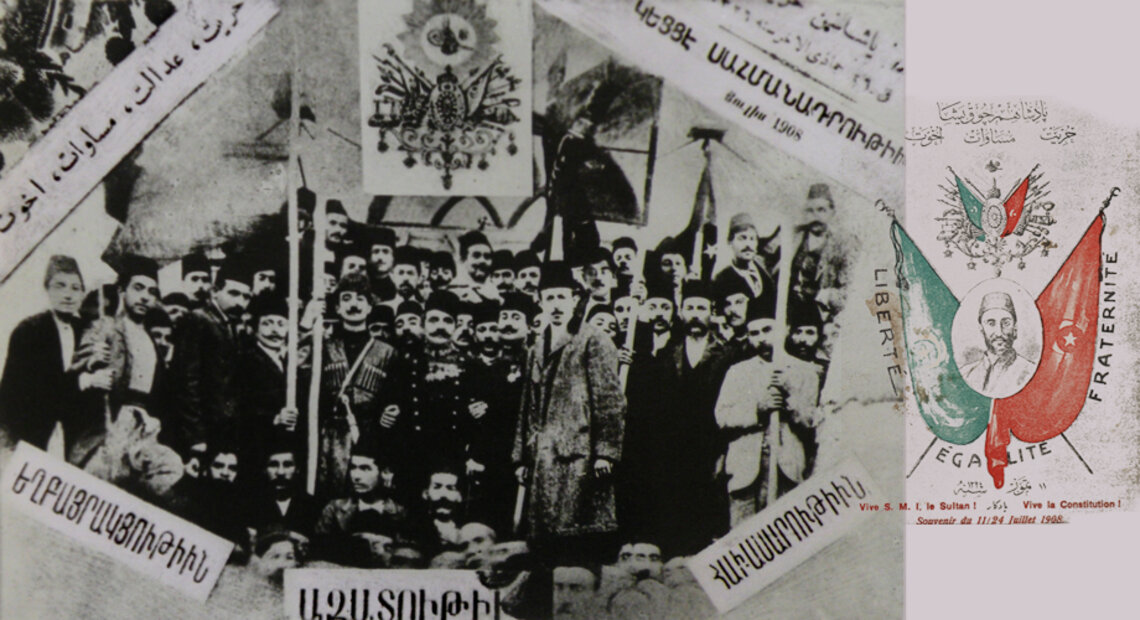

On December 17, 1908, Tlgadintsi (Hovhannes Haroutiunian, born in Tlgadin/Khuylu/Kuyulu in 1860 and killed in 1915), in a letter addressed to a friend writes: “In the evenings, we can find our back home without worries. Isn’t this enough?”[1]. Constitutional order has been established throughout the Ottoman Empire and Tlgadintsi’s observation refers to the persecutions, betrayals and arrests that occurred during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II before this historic event. This principal of the Central School (in the Upper or St. Hagop District) had bitter memories of these incidents.

The collapse of the old dictatorial regime was an unexpected and marvelous surprise for the local Armenians. The situation is best explained in the following words of another Harput notable, Hovhannes Bujicanian:

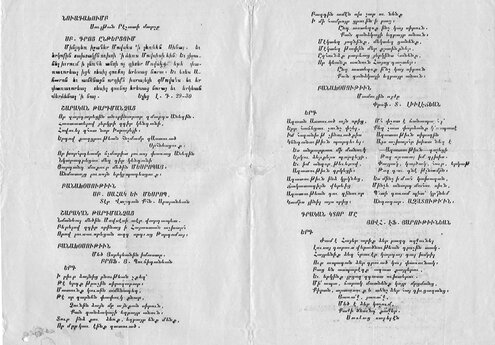

“The magnificent constitution, with its magic wand, raised us from enslaved subjects to free citizens. July 11, 1908, not only has opened a wide horizon of privileges and incomparable opportunities, but an enchanting vista of things to come within our sights (…)”[2] Hovhannes Bujicanian (born in Çüngüş/Chnkoush in 1873 and killed in 1915) was a high ranking authority at the local Euphrates College and a prominent representative of the Protestant community.

The removal of the Hamidian regime was truly a political and psychological life-changing event for a people who for decades lived in despotic conditions. In the months that followed, one could already observe signs of this change in Harput's everyday life. Armenians started to feel relatively more secure, which inspired self-confidence and prompted people to take steps they had avoided in preceding decades. Thus, of symbolic importance is that we see more windows being installed in village homes and an increase in two story homes being built, in contrast to the proliferation of subterranean houses up till then. [3] In the past, Kurd or Turkish aghas and beys generally only had such houses, while Armenian peasants were cramped in their one-storey windowless homes dug underground.

The change is especially evident in the educational field. Life in the schools built adjacent to village churches becomes more active. Even during the Hamidian period, Harput stood out due to its extensive network of Armenian schools. However, if the schools in the towns (Harput and Mamüretülaziz) represented developed institutions according to concepts of the time, village schools in general still operated on pre-modern, traditional lines. The enthusiasm ushered in by the Ottoman Constitution immediately changed this situation, and the old schools functioning in the villages of the Harput Plain were renovated or built anew. [4] Schools for girls were opened in many villages. Teachers, both male and female, graduating from the colleges in the towns are invited to take up positions in the villages. [5]

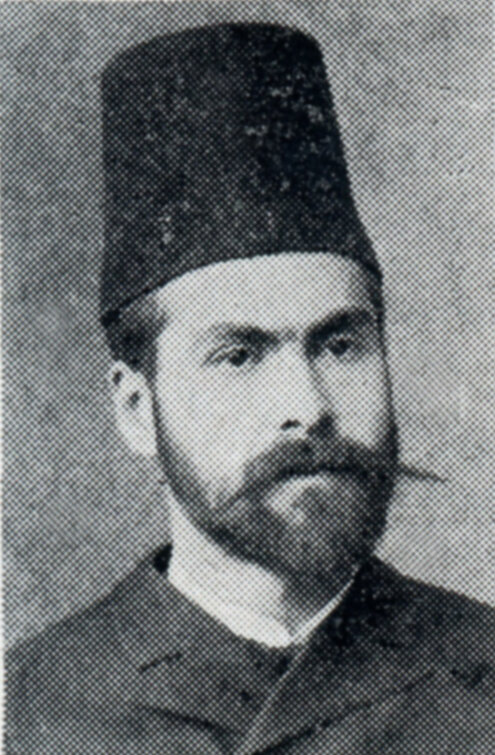

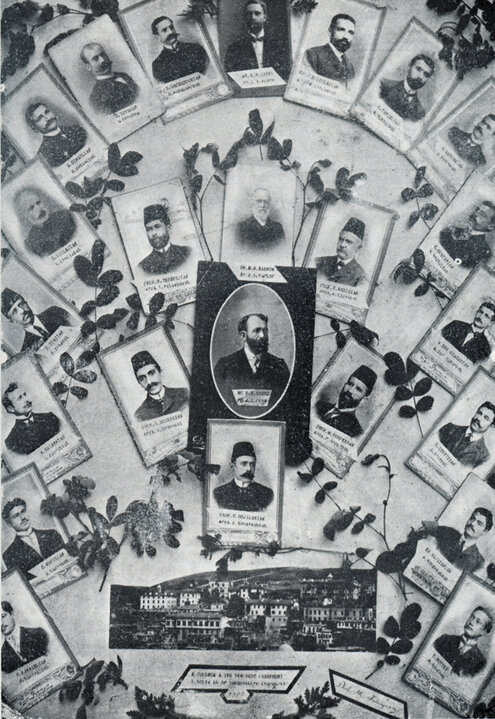

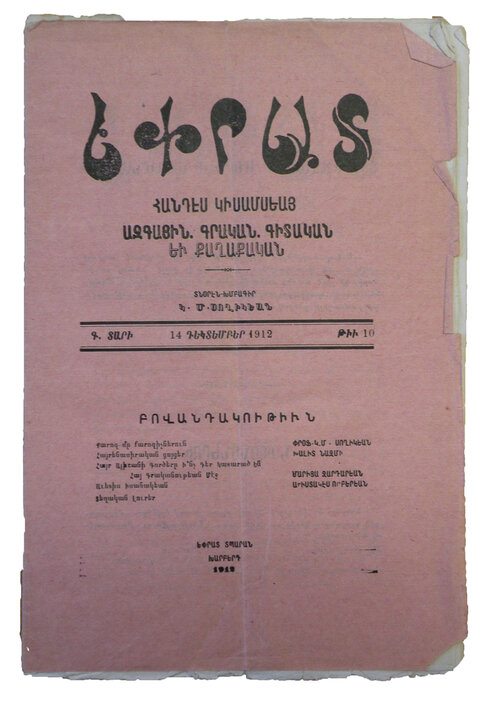

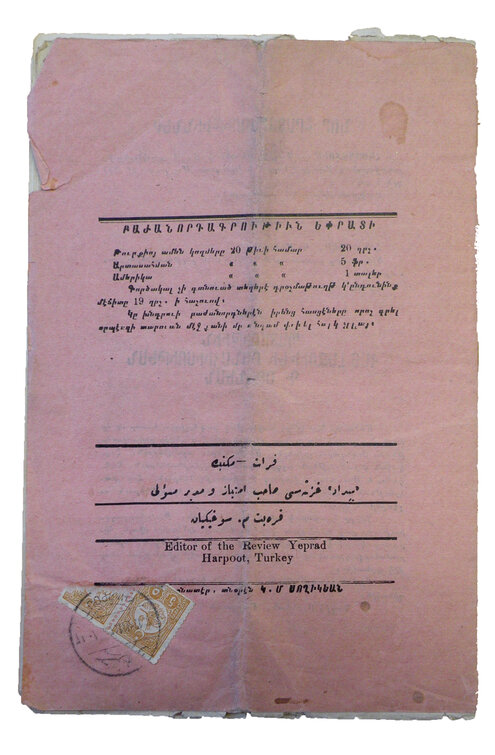

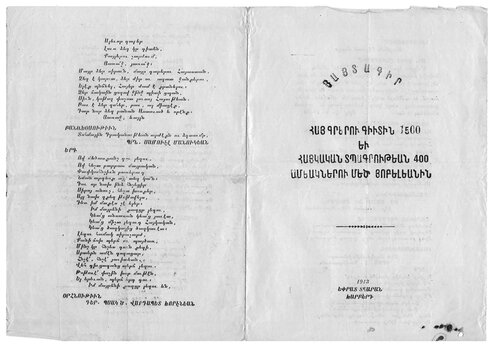

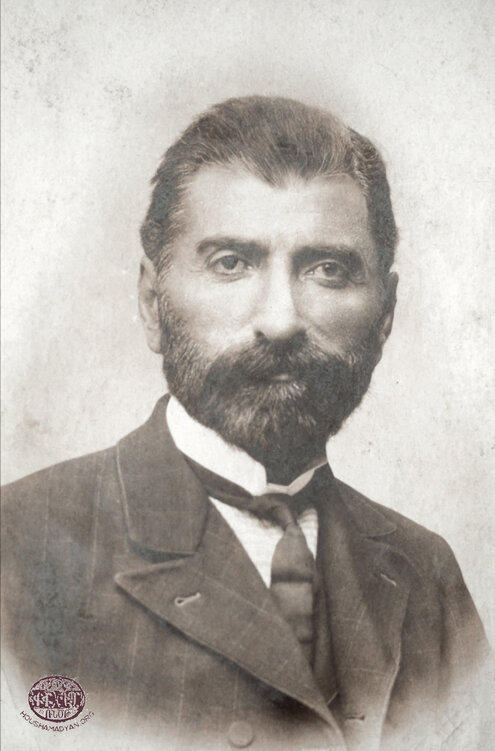

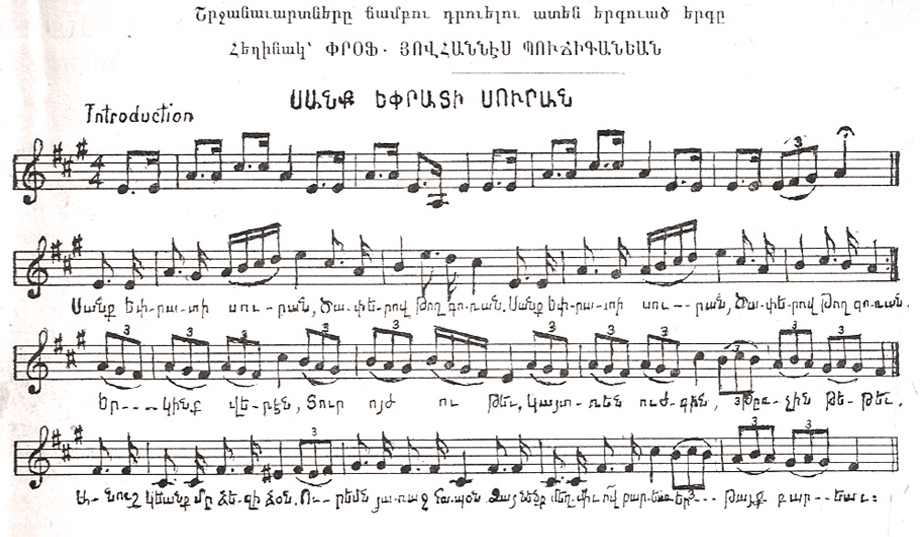

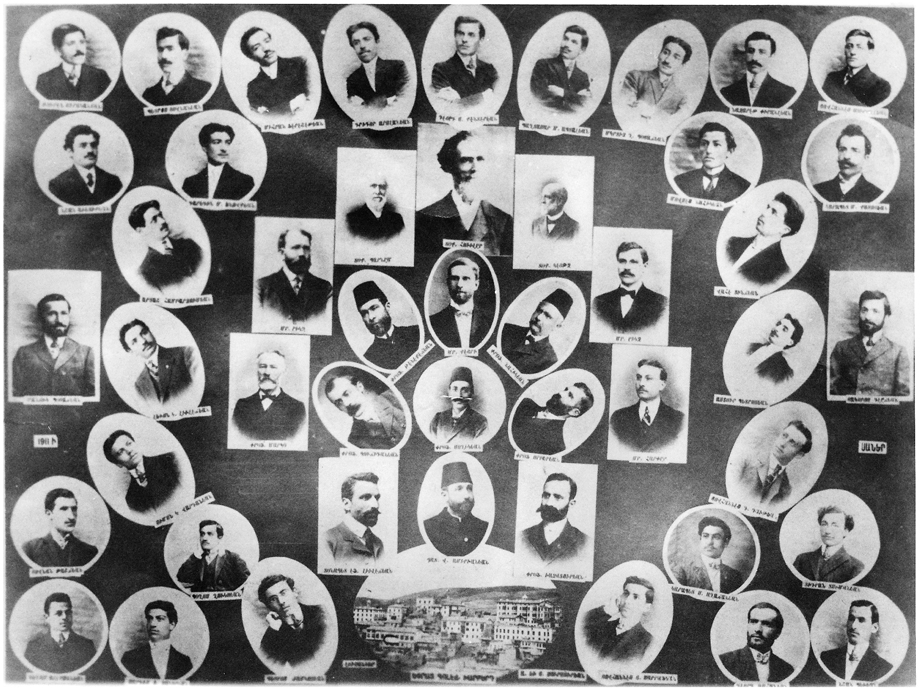

The Ottoman Constitution allowed for formerly banned initiatives in town schools as well. In 1909, an Armenian printing press started operating in Euphrates College, which prints the college official newspaper Yeprad (Euphrates). Prior to this, starting in 1891, the college had published a handwritten and collotype periodical called Asbarez that did not withstand the prohibitions of the Hamidian regime and shut down soon afterwards. Yeprad is considered its natural continuation and the first issue was printed on November 1, 1909. The editor of this semimonthly periodical was Garabed M. Soghigian (born Harput 1868-killed in 1916). The staff included Donabed Lulejian and Hovhannes Bujicanian. In addition to the paper, the college press produced circulars, bulletins, religious and grammar books, and novels translated into Armenian. Every day, on average, 3,000 pages in Armenian were printed. [6]

New school subjects, corresponding to the new openness ushered in by the constitution, became a part of the curriculum at this college – Turkish Law and Parliamentary Law were subjects taught by Nigoghos Tenekedjian. [7]

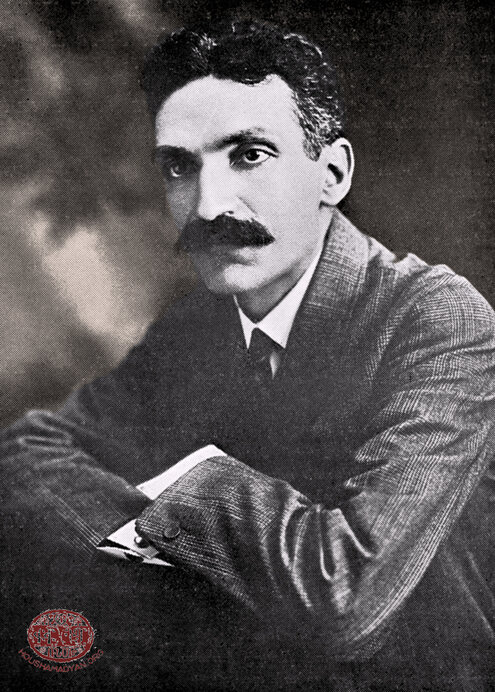

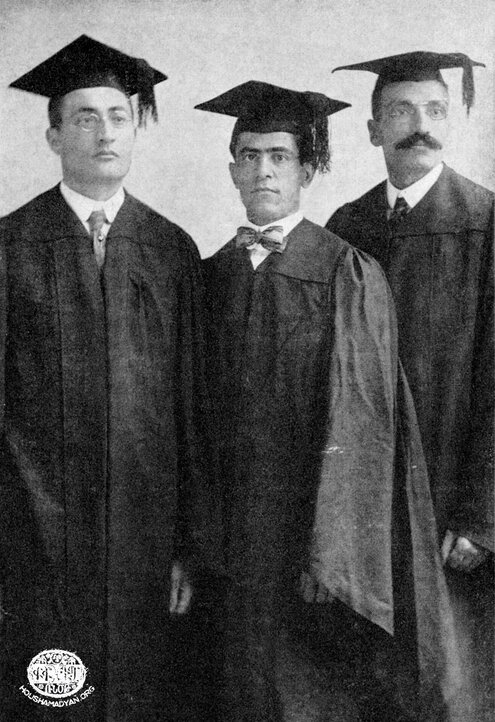

Donabed Lulejian, who was an Armenian luminary in the town of Harput, a teacher at Euphrates College and a member of the local “Euphrates” freemason lodge, also experienced this jubilation of new-found freedom. In 1910, he was studying in the United States, first at Yale and later at Cornell, and sent his congratulations to the college graduates back home. In his letter he already sees new prospects for the missionary institution to play in the region. In 1912, he left the United States and returned to his native Harput. “In constitutional Turkey, the Euphrates [college] now has a wider field of activity and a more glorious rank.”[8] He saw this new role mainly in the agricultural sector, as the people living on the Harput plain were mostly farmers. He saw the necessity of supplementing the college with farming and animal husbandry divisions. “The farmer will change his plough handles and ploughshare and will adopt new methods, to make the earth more bountiful” [9].

The forming of Armenian theater companies was also considered a development of the new times. Instead of the limited number of theatre groups, new companies were formed in the towns and many villages in the post-constitutional period. They often operated in a school setting, but their audiences attracted society in general, mostly Armenians, but also members of the non-Armenian elite. Armenian patriotic plays were performed. Such performances could have led to outright arrest under the former regime. For example, The Wound of Armenia (Khachadur Apovian) and Black Earth (Bedros Tourian) were performed in the hall of the Hussenig School. Besides, European classical plays were performed in Memüretülaziz, such as Friedrich Schillers’ The Robbers or William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Furthermore, the Armenian religious holiday of Vartanank was imbued with a new spirit and turned into popular gatherings during which a play on the same subject, was performed. [10]

The slogans of the Constitution were echoed as far away as in the United States, where thousands of emigrants from Harput had relocated from the 19th century. They were mostly laborers working in factories along America’s east coast. Many of them considered the time appropriate to return to the homeland and start a new life with their families and relatives with the money they had earned abroad.

The new atmosphere of freedom also impacted the political-organizational life in Harput. Armenian political parties that formerly operated underground and were persecuted opened their offices in Armenian populated towns and villages. By the end of 1908, the ARF and the Henchag Party had clubs in Mamüretülaziz. The same parties opened clubs in the town of Harput and the village of Pazmashen. In addition to clubs, political groups were formed in villages and towns. Political activists travelled freely and gave lectures about current political issues. [11]

The fear and uncertainty regarding the days to come

As was the case with all Armenians living throughout the Ottoman Empire, the 1909 massacre of thousands of Armenians in the Adana region dealt a heavy blow to the jubilation by Armenians in the Harput region. A feeling of collective confusion and distrust towards the future became palpable. This mentality was also expressed in the memoirs of Harput Armenians and other writings (press articles, lettres) of the time.

This is not to say that the Constitution was welcomed with equal excitement by all Armenians. Many regarded the new freedoms with suspicion. Doubtlessly, this mistrust was directed at the leaders of CUP (Committee of Union and Progress) who took over the reins of power in the empire and the non-democratic modus operandi they adopted.

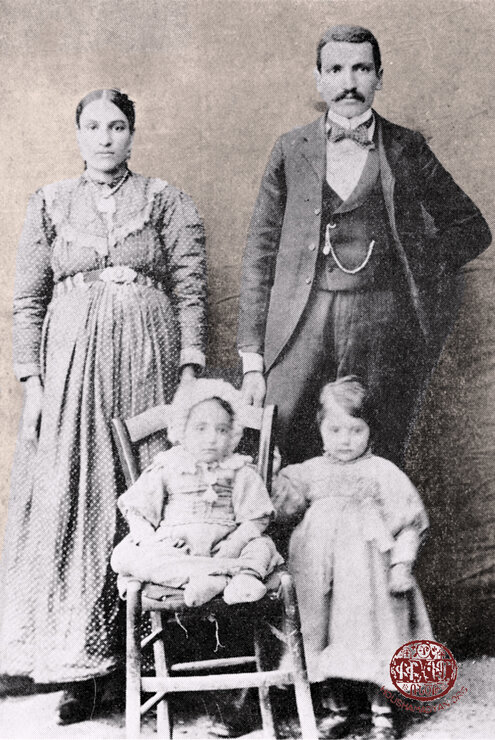

1) Donabed Lulejian with the family of his elder brother Dikran (1868-1908) in Lynn, Massachusetts, USA. From left: Maritsa, Victoria, Araksi, Donabed. First row – Albert (Source: Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915 [in Armenian] Fresno, 1955)

2) Donabed Lulejian (Source: Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915 [in Armenian] Fresno, 1955)

Viewing things from Harput, as we will see in following section, there were many reasons for uncertainty regarding the unfolding situation. While some found a way out by emigrating, others (and here we refer to Armenian intellectuals of Harput) sought a solution to the problem by improving local conditions. In this context, when we examine the discussions that took place at the time on the Armenian stage, we note the following dominant line of thought – the strengthening and solidification of the state, the Ottoman state. This may seem a bit contradictory, especially in hindsight, but the jubilation created by the Ottoman Constitution hadn’t completely waned. Many Armenians, including prominent figures from Harput, were convinced that the best guarantor for improving their daily living conditions and their human and cultural rights was the forging of a strong state. But from their perspective, the stress placed on the role of the state did not mean the development of a centralized state authority that, in the name of country’s welfare and security, would be ready to intervene to the detriment of democracy and in opposition to individual liberties. Such a “law and order” state was the CUP’s much desired one party rule. The course of developments would show that this dictatorial tendency gradually became the reality throughout the empire’s domain. From the vantage point of Harput intellectuals, the guarantor of a powerful state should respect the law and defend constitutional rights. The influential presence of state institutions should be extended to villages, preventing all types of anarchy and violations of the law. “Without these freedoms and rights, the constitution is a joke; freedom a dead element and the truth a lie,” [12] Bujicanian writes in 1912. Naturally, one could find differences amongst the various Armenian ideological currents at the time. Nevertheless, the majority of the voices expressed in Harput pointed to the strengthening of state institutions as the key to the solution.

Another important view-point, expressed directly or indirectly during these discussions, saw the future of Ottoman Armenians within the boundaries of the Empire. In the majority, the concept held sway that given the conditions of the day there was no solution to the Armenian issue outside the Ottoman Empire. The freedom of 1908 had unchained their voices. They boldly expressed themselves on national (Armenian) issues and the future of the nation. The words “nation” and “national” weren’t used with their modernist meaning. Rather, we must understand them to mean “proto-nation” and “proto-national”. In other words, they should be understood as the Armenian community and its cultural values within the hybrid Ottoman environment. We must take this into account especially because in this article we encounter the use of these same words by Bujicanian and Lulejian. But when the discussion turned to matters of the “homeland”, oftentimes a dual meaning was evident. Sometimes reference was made to the Armenian homeland, i.e. those historic lands on which Armenians lived at the time. Elsewhere, it was clear that the concept of “homeland” referred to the Ottoman homeland – the ideal brought about due to the new constitutional order. Donabed Lulejian provides a good example of this situation. This teacher at Euphrates College escaped in 1915 and took refuge in the Dersim Mountains. There, on slips of paper, he begins to write down his memoirs that were never completed or published by him. In 1917, in Garin/Erzurum - at the time under the control of Tsarist Russia - he contracts typhus and dies. The following lines are taken from the chapter “Prison Memoirs”, where he presents the general sentiments in Harput before the Genocide. These sentences were written in Dersim, when the mass killings of Armenians at the hands of the Ottoman authorities hadn’t yet finished and the wounds Lulejian received while tortured in jail hadn’t yet healed.

“It was not the demand of an independent Armenia that inspired Armenians. Each Armenian desired this but all reasonable individuals knew that such wasn’t possible given the circumstances at the time. The term independence was [only] a concept for them. They were resigned to and convinced of the idea that the Armenian will live with the Turk and that the interests of the Armenian and Turk must be reconciled. Not every Armenian desired foreign rule. Turkey was the only and best homeland for them and if the Turk gave the Armenian that position to which the Armenian aspired, then the Armenian would have stopped loitering around foreign doors. He demanded equality, citizen rights, and wanted an end to religious intolerance, the lifting of darkness, for Turks and Armenians to collaborate for the economic and political development of the country. This was the dream of the Armenian; this is what he strove for.” [13]

Donabed Lulejian also wrote about the importance of Turkish-Armenian understanding earlier, in 1910, in Harput. “The groans of the dreamt Freedom, Fraternity and Equality will continue for as long as that desired understanding is lacking.” [14] The lack of understanding was a serious concern for him since “These circumstances will cause continued economic crises and storms, and will be the reason for the destruction of the two races.” [15]

It is clear that, from an Armenian perspective, the strengthening of such understanding would first and foremost derive from the creation of mutual confidence. During the post-constitutional years, when Lulejian wrote the above mentioned lines, one shouldn’t view the Armenian demands for cultural, economic and political autonomy as a threat to the Empire. These demands derived from the collective consciousness of one primary group that constituted the Empire, and their implementation, on a variety of levels, would have made the collective participation of this element much more practical in terms of strengthening and enriching the empire. Here, it is instructive to recount one episode of the life in Harput to portray this dichotomy that existed between the Armenian elite and the CUP regarding the conceptualization of the constitution and its interpretation.

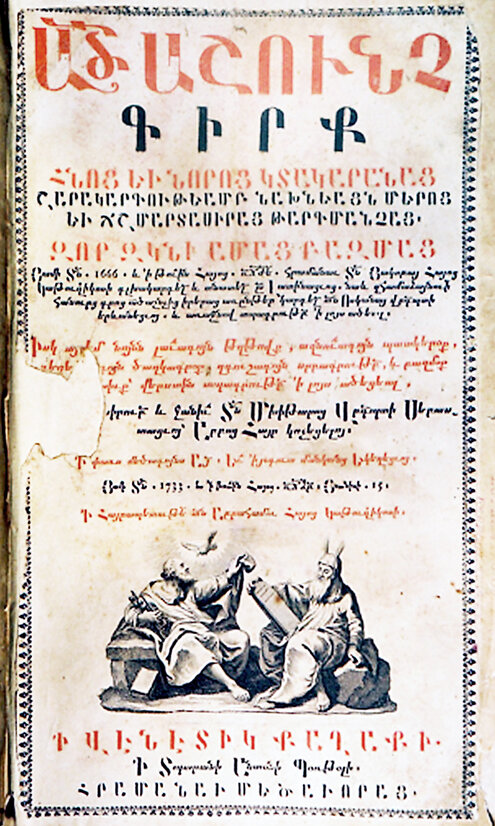

Mezire (Mamüretülaziz), 1913. In the courtyard of the Capuchins’ college on the occasion of the celebration of the 1500th anniversary of the invention of the Armenian alphabet. Rev Karekin and Rev Ghevont, Père Raphael and Archpriest Bsag Khorenian can be seen, standing next to one another, deep in the picture. The remainder are the students and teachers of the French college and the Central School. The sign on the left of the picture is inscribed with the Armenian alphabet, and the one on the right says ‘Come, let us live for the children’ (Source: Private collection. Courtesy of Dzovig Torikian)

In 1913, all larger Armenian communities celebrated the 1500th anniversary of the creation of the Armenian alphabet in grand style. The Harput region with its rich educational institution, would participate as well. On October 13 (October 25 according to the Gregorian calendar) a grand procession of students, pupils and college students took place, while at the same time, accompanied by the sound of the church bells. At the head of the procession were the college students, one of whom carried a banner emblazoned with the Armenian alphabet. Another student held the purple-red flag of Euphrates College, and a third the Ottoman flag. Other students held aloft pictures of Mesrob Mashdots and Sahag Bartev. [16] The procession wound its way through the streets of the town. Especially visible was the brass band of the Capuchin School. The 1,500 strong procession marched past the municipal building and the governor’s office and then entered the market, all the while singing songs in Armenian. When they reached the Turkish Sultaniye School (state-run secondary school), the marchers shouted out in unison “Long live the Sultan, long live St. Sahag and St. Mesrob”. The procession then headed towards to the neighboring town of Hussenig where pupils from the Armenian schools joined in, returning to Harput town together. Celebrations continued the next day. Armenian school teachers from the villages arrived. The Armenian primate from Mamüretülaziz and many prominent personages travelled to Harput. Speeches were made and the Tarkmanchats religious hymns (Translation canticles) and Armenian patriotic songs were sung. [17] The celebration was essentially an Armenian occasion to mark one of the most significant dates of Armenian culture. The following words of Hovhannes Bujicanian, spoken before the crowd of celebrants, capture the spirit of the day.

Hussenig – 1912. Local theater group stages performance of Zoravar Antranig. Seated (from left): Nerses Baghdigian, Krikor Bezigian, Hagop Deranian, Kevork Deroyan, Mihran Tufenkjian. Standing (from left): Mihran Madoyan, Garabed Portoyan, Ohan Mazmanian, Haroutyun Bayboudian, Bedros Rsdigian (Marderos Deranian archives, NAASR, Belmont, Mass.)

“Great jubilees give life to a fresh national spirit grown drowsy, numb and extinguished. A people without national spirit are a living corpse. It neither has a national life or progress. A national history and literature, songs and traditions, morals and customs, a national Church and school, are truly the temples that keep this spirit alive (…).” [18]

Other speakers were Father Vartan Arslanian (Born in Agn/Eğin in 1863, killed in 1915) and Tlgadintsi, who delivered similar speeches. When it was Donabed Lulejian’s time to speak, he, noted:

“October 26, 1913 will mark the era of the Armenian renaissance. This jubilee’s grand gala marks the reawakening of our self-consciousness, true patriotism, freedom of conscience, and intellectual progress. The treasures of the past are now ours. We are the inheritors of the written word and the press; the intellectual works and experiences of our Armenians belong to us. Like wondrous beams of light they enlighten our surroundings, they inspire us, encourage us and push us forward to carry out our duties expediently.” [19]

In fact, the Ottoman Constitution opened new horizons for Armenian collective life, the most important being cultural freedom and its unhindered progress. The magnificent celebration marking the Armenian alphabet was a clear expression of the new times. Armenian organizers spared no effort in imbuing this celebration with decorum. Held in the streets of Harput, they made the celebration an expression of cultural pride. A public gathering on such a scale hadn’t been seen in the town in the post-constitution years. However, we clearly see that Ottoman symbols had been preserved. That’s to say, the organizers of this public celebrations fully understood that the CUP circles could unleash collective condemnation against the Armenians at any moment, arguing that such celebrations were clear manifestations of Armenian separatist tendencies.

1) Tlgadintsi (Hovhannes Haroutiunian, 1860-1915) (Source: Nubarian library, Paris)

2) 1733 Bible printed in Venice. Once belonged to the Euphrates College library. Bujicanian family members who survived the Genocide saved it. It is now in the possession of Adom Boujikanian, a grandson of Hovhannes Bujicanian, who resides in Montreal.

However, these calculations on the part of the Armenian organizers proved to be incorrect. But we will come to this later.

For the intellectual circles of Harput, the main issue was the strengthening of the constitutional-democratic order in the Ottoman Empire. Thus, for Hovhannes Bujicanian, the constitution was firstly an historic occasion to work for the prosperity of the empire. “The constitution isn’t verbiage, and verbiage isn’t the constitution. The constitution is an opportunity that will ascertain whether the Ottoman state and the nationalities that comprise it have the virtue and right to live, or whether they are doomed to die,” [20] Bujicanian writes.

With this aim in mind, it was imperative for the people to be politically vigilant so as not to lose this historic opportunity. Bujicanian pointed out that the people must be provided cultural, religious, literary and artistic nourishment, and that a civic consciousness and spirit must be awakened in them in order to create a healthy public life in the country. “We need civic halls in order for public life to grow strong. We need civic spirit in order for the nation to grow strong. We need public opinion in order for the constitution to take root,” [21] writes Bujicanian in 1909. He believed that education and progress played a huge role in forming a model Ottoman citizen. “First light, then freedom. First education, then the constitution.” [22] His friend, Donabed Lulejian, thought quite alike on the topic.

“The present century searches for [the well-being of society] in intellectual development. It is this desire to reach that dreamt about well-being that spurs individuals, communities and governments to exert every effort to universalize and popularize intellectual education. Village primary schools, town schools and higher institutions are the result of these efforts aimed at spreading the sciences, trades, art and learning, and to cultivate understanding and knowledge.” [23]

1) First page of article handwritten by Hovhannes Bujicanian (Source: Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works [in Armenian], Beirut, 1974)

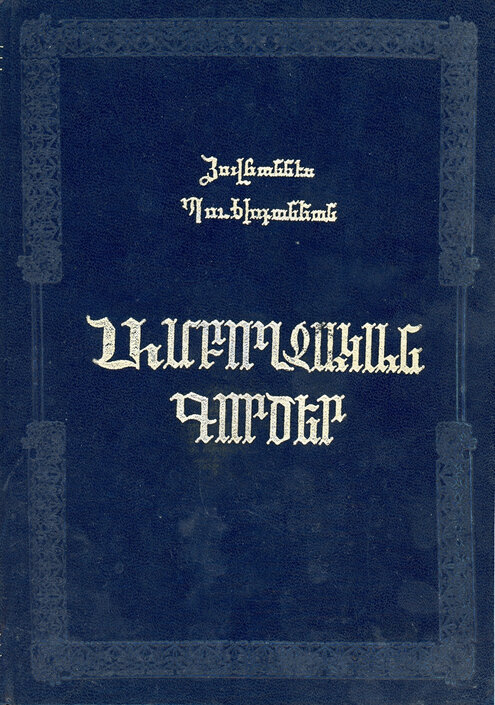

2) Հասկաքաղ Բրօֆ. Տ.Կ. Լիւլէճեանի (Բագրատ). գրական վաստակը եւ 1915-ի բանտի յուշերը [Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915], Crown Printing, Fresno, 1955

The freedom to express one's opinion was a fundamental necessity for Bujicanian. The problems of the country had to be discussed freely and publicly, without constraints. The same held true regarding political life, where the parliament should become the platform for political give and take and thus prevent any manifestation of violence. Bujicanian had studied philisophy and psychology at Edinburgh University between 1906 and 1908 and had become a supporter of the democratic institutions of Great Britain. He believed that there was a need for “conservative and liberal parties” for the development of Ottoman political life, given that their existence was an important incentive “for correcting each other’s errors and finding truth”. [24] “These two parties need to defend their views freely and in fact. The constitution stands on the anchor of free debate. From the clash of opinions, light will be born in the assembly of deputies.” [25] For Bujicanian, the constitution was a synonym for democracy. In essence, he believed in a political life developing under democratic conditions where diversity of opinion was respected.

At first glance, these can be viewed as conventional ideas, but Bujicanian and countless other Armenians like him realized that they lived in tumultuous times and that their much-cherished state of law and rights had not been fully formed. They were concerned that democracy, and with it, the future of Ottoman Armenians was in a downward spire. In Bujicanian’s opinion, the constitution was at risk: “(…) reactionary sharp thorns are in position, threatening to suffocate it. Fanaticism is so entrenched in the hearts and minds of the dominant elements that the ideals of equality and fraternity are unrealizable and remain incomprehensible.” [26] And after all this, a pessimistic prospect for the future opened before him: “Old problems demand new blood. Old hatreds mandate a new sacrifice. New blood stirs up memories of old problems and the notion of settling problems and justice are stressed even more in the bloodied hearts. Hope and the political chaos meet and hope starts to fade.” [27] Clearly, here Bujicanian was alluding to the killings and massacres of which the 1909 Adana massacre was the major one. Fear, uncertainty towards the future, is stressed more in his thoughts. “There is a volcano on the bottom of our country, and thunder roars in the sky. Chaos reigns over the surface. Flashes of light are to be found merely here and there. It is still night in Orient and the scarce rays of dawn, the beams of freedom and civilization, shine on the political horizon. Only God reads the fate and future of this country.” [28]

The Land Issue – Mirror of the CUP’s Policy

How to halt this precipitous process of events? Every diversion from constitutional principles placed the Ottoman Armenians before a new set of tragedies. Our Harput Armenian memoirists realized this, but at the same time they had become passive observers of this process of events. The elite of the CUP made their positions more severe day by day. The prospect of Armenians, Turks and others living and developing side by side throughout the empire was essentially torn asunder. Gradually, Armenians were portrayed as a disruptive element preventing the development of the empire. Their cultural, economic and educational abilities were no longer seen as enriching impulses. On the contrary, they had become threats for the CUP's vision based on Turkishness and Turkification. For the CUP leaders, the entire issue had become a struggle between Armenian and Turk. In his memoirs [29], Donabed Lulejian called the CUP approach a “Struggle for Life”, and we get the impression that when he wrote these lines he had already fully grasped the CUP ideology and their ideas that paved the way for the implementation of the Armenian Genocide. Moreover, we get the impression that Lulejian was already familiar with the works of CUP ideologues Yusuf Akçura or Ziya Gökalp and their ideas influenced by social Darwinism and the inevitability of natural selection among peoples.

There was fertile ground in the Harput region for the spread of this line of thinking. Local Muslims could not match the Armenians’ economic and educational strength. This inflamed the suspicions and jealousy of the CUP administrators. The silk and cotton factories owned by Armenians in Mamüretülaziz and Harput, the iron foundry, the presence of Armenian merchants, Armenian tradesmen everywhere in the towns and villages, the development of a rich and unprecedented Armenian educational network within the region, and the inflow of money and economic skills from the United States, had all become thorns in the eyes of the local CUP administrators. The national bourgeoisie, [30] a Muslim middle class, which the CUP ideologues were seeking to support hardly existed in the region. Instead, as Hamit Bozarslan noted quoting CUP thinkers, there was a Christian “aristocracy” that was seen as suppressing the Turkish (and/or Muslim) “Third estate” (tiers états). [31] Even though Armenian-Turkish harmony continued on a ‘formal’ basis, all it would take was a radical change in conditions so that the nuances of CUP understanding of the Ottoman state would appear explicitly.

Prior to this, as viewed from Harput, the reforms brought by the Constitution were only skin deep. A number of fundamental problems remained unresolved. The land issue or the “agrarian question” was one of the most important of these. It was also a primary issue taken up during CUP-ARF negotiations; the Armenian side always stressing the need for a quick and radical solution. In a decision adopted regarding the land issue at the Sixth World Congress of the ARF held in Istanbul in 1911 (August 17-September 17), we read: “(…) if these unparalleled deprivations resulting from exceptional Hamidian pressures are not healed by extraordinary means, the benefits promised by the Constitution will remain a dead letter for the Armenian people (…).” [32]

The Ottoman state system was weak in the village regions of Harput, and the absence of the central authorities was the major source of general insecurity. What ruled instead was the power of the local beys and aghas (Turks and Kurds). They owned the majority of the region’s fields, gardens and orchards. Most of the Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish villagers were tied to them by the status of maraba. Only a tiny portion of the harvest was the property of the villager. The greatest benefit expected in the villages of Harput from the Constitution was the successful solution of the land issue. Deep down, it wasn’t merely the Armenian peasant that had expectations from this new political regime. Disenfranchised Turk and Kurdish villagers also found themselves in the same situation. [33] The establishment of the new order naturally caused serious concerns in the feudal circles – mainly among some Kurdish tribal chiefs – that had reached privileged positions during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II.

1) Back row – Donabed Lulejian and wife Yeghsa. Front row – Their children, Hrachia and Ara (Source: Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915 [in Armenian], Fresno, 1955)

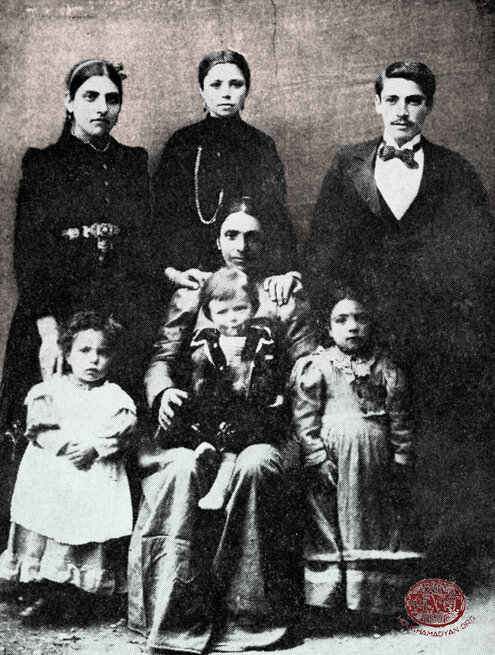

2) Donabed Lulejian’s sisters Aghavni Terzian and Mariam Gostanian with their children (Source: Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915 [in Armenian], Fresno, 1955)

In many Armenian villages the authority of the beys and aghas was challenged. They ruled over just one portion of the lands and suffered due to economic crises. After 1908, Armenian villagers began to take collective steps to struggle against their beys and aghas. Legal means usually proved futile, especially if the bey or agha in question continued to maintain his authority. They had the full backing of the local authorities and courts through bonds of friendship and family. Given such conditions, individual and collective claims by Armenian villagers achieved little. [34] The constitution, however, had given Harput Armenians the chance to engage freely with their compatriots (hayrenagits in Armenian, hemşeri in Turkish) and relatives who had emigrated to the United States. They hence received financial assistance. Compatriotic unions representing the villages of Harput had been established in many American cities. From 1908 onwards, they became much more engaged in improving conditions in their native villages. Most financial assistance was allocated to the village church or school, but also to the overall efforts to regain lands taken over by the agha or bey. After 1908, the villagers of Pazmashen for instance regained their fields in such a manner. In exchange for money, the aghas of Dzovk/Gölcük gradually returned Armenian lands. Such radical changes occurred in many villages; including Tadem/Tadım and Parchanj (present-day Akçakiraz). [35]

This approach was not always successful however. In Charsanjak, to the north of Harput, a solution to the land issue remained unsettled. Community efforts to free some 25,000 Armenians from the status of maraba were met with insurmountable hindrances taken by local state bodies.

In essence, the socio-economic structure that existed in the past was maintained intact by the new regime. From the perspective of the Armenians, as well as common Kurdish and Turkish villagers, this structure was the main source of injustice and exploitation. The new development after 1908 was that the Armenian community organizations of Harput and Charsanjak directly took the responsibility of settling this issue on behalf of the villagers. These bodies frequently petitioned local and central authorities to find a resolution of the land issue. There is the widespread notion that the CUP leadership was ready to resolve the land issue in the first few months after the establishment of constitutional rule. Later, however, forging friendly relations with the Kurdish aghas and powerful tribal chieftains and not antagonizing them became the CUP’s primary task; to the consternation of the peasants made landless by them. [36] Clearly, the CUP brass was playing a double game. One the one hand, it negotiated with Armenian political leaders, while placating the Kurdish aghas and beys. [37] The passive stance of the local authorities in Charsanjak simply allowed the beys and aghas to increase the exploitation of their maraba Armenians. They could no longer tolerate the fact that their former subjects were now openly and talking boldly about their rights. Thus, in the post-constitutional period, the Armenian villagers of Charsanjak were subject to an intensified round of attacks, killings and thefts. The state authorities took no measures in response and these transgressions went unpunished.

The Armenians of Harput, at the time, were following events unfolding in the region. From 1911 onwards, the land issue became a hot topic in the Armenian press. The situation faced by the Armenian villagers of Charsanjak was unsettling for Armenians in Harput. In fact, on a political level, Harput community leaders did their best to defend their compatriots to the north. [38]

Up until the start of WWI, the Armenian community organisations were not able to achieve any progress in resolving the land issue in Charsanjak. Those Armenians engaged in the matter felt that the local feudal lords not only enjoyed the support of the local administrative apparatus, but also that of the central authorities in Istanbul; especially of the dominant CUP leadership. [39] In this context, various sources and memoirs of the day recount the following incident that shook Armenian political circles in Harput. In 1911, Abdul Ghani Bey, a local CUP leader, declared at a meeting of the party’s local chapter that the land issue in Charsanjak could only be resolved by means of a massacre. While the CUP leader did not use the word “massacre” outright, he portrayed what he meant by moving his hand across his neck in a cutting motion. News of the incident was later spread by others attending the meeting. [40]

The unresolved land issue soon intensified the already tense situation in the eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire where Armenian villagers were at the mercy of Kurdish feudal chieftains. In 1908 Kurdish tribes in the Dersim region north of Harput rebelled. The first victims were the local Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish residents. [41] Thefts against Armenians in the villages of Harput increased. Individual Kurds would frequently rob Armenian homes, fields and gardens. [42] Against this general backdrop we must also note the 1909 Adana massacres had propelled Armenians to be vigilant and strengthened the view that security of life was not guaranteed under the new order. Given these conditions, the Armenian political parties, the ARF and the Henchag Party, launched a drive to arm Armenians in these regions. As in many Armenian populated towns and villages, the arming of Harput Armenians began. Bringing weapons to these regions was a violation of the law, but was often done openly and with the knowledge of the local authorities. For example, it is recounted that trunks of weapons filled the Harput market for many days. Armenians in the villages carried their weapons around brazenly. They often visited state institutions while carrying a gun. Guns were fired during festivities and weddings out in the gardens. In the fields, weapons training classes were organized. The weapons were brought from Istanbul or secretly purchased from the Ottoman garrison in Hussenig. The rifles were mostly of Greek manufacture (Gras), or the German Mauser type. In the town of Peri, to the north, Turkish and Armenian residents armed themselves with the aim of collectively stopping an expected Kurdish assault. A similar event is recorded in the mixed Armenian-Turkish village of Touma-Mezire in the Çemişgezek region. [43]

The ultimate phase

It is impossible to write about events and daily existence in Harput without some reflections on the Genocide, which terminated all local Armenian life. While we do not seek to provide a detailed description of those final affairs, we will raise some points that relate to a few thoughts broached in this article.

In the first place, we deem it necessary to continue examining the issue of Armenians being armed, given that this would serve as one of the main reasons for arresting and killing Armenians in May-June 1915. The issue would also lead to the intensification of regional anti-Armenian sentiment, in preparation for the final act – mass eviction and massacre. Thus, after the declaration of general conscription, thousands of soldiers were assembled in the Harput Plain, preparing to join the Ottoman Third Army on the Russian-Turkish front. The Hussenig garrison could not adequately house these soldiers so they were given tents to be set up on the adjacent hills or in village homes. In the town of Harput, the buildings of Euphrates College were requisitioned by the government and 4,000 Ottoman soldiers were barracked there. [44] After war broke out on the Russian-Turkish front, wounded Ottoman soldiers were taken to the Harput area. In a short time, daily life in Harput, as elsewhere throughout the empire, was torn asunder by these military dislocations and government requisitions for the war effort. But the devastating defeat of the Ottoman Army at Sarıkamış only fanned existing anti-Armenian sentiment. The main reason for the defeat was soon credited to the “treason of the Armenian soldier”. In his memoirs, Donabed Lulejian writes:

“For a Turk from Harput, the enemy was far away and unnoticeable. But there was an enemy right by their side (…). It was the Armenian, with his cross, with his belfry, with his schools, with his prosperous economic progress. When the enemy seized land from his country, the Armenian also seized rights from them. He snatched freedom and rose from the level of slave to that of a citizen. It was necessary to bring him down; he had to fall to the status of a slave (…). The Jihad had inflamed the Turk’s hatred against the Christian World. The Turk of Harput manifested that hatred against the Armenian of Harput. He strove to triumph over him.” [45]

Euphrates College complex, Harput (Source: Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915 [in Armenian] Fresno, 1955)

A few weeks after war was declared, the Capuchin missionaries of the Lower District of Harput left the town. Local Turks immediately broke down the door of the Capuchin church and threw the church bell down to the ground, trampling it underfoot. The same local Turks attempt to remove the cross atop the church. Mayor Asaf Bey personally removed the wooden cross from the altar, broke it, and stood on it. Such symbolic acts increased. Local Armenians, however, remained passive, silent observers of events happening around them. When Armenians took to rebellion in Van, persecutions intensified also in Harput. Word spread that the Armenians in Harput were also preparing for an armed rebellion. On this issue Lulejian writes in his memoirs that CUP inspectors reach Harput in April and hold a secret meeting, attended by Turkish officials, prominent individuals, Kurdish aghas and tribal chieftains, in the CUP club. [46] It is at this meeting that Armenians are declared as enemies of the Ottoman homeland. A terrible process soon follows; the local authorities, in response, unleashed mass arrests of Armenian notables, inellectuals, community activists [47].

Were Armenians aware that this was the final stage, to be followed by total extermination? If there was such awareness should they have rebelled? We know that the matter was debated by Harput’s leading citizens and that a majority were opposed to rebellion. They believed that to rebel was foolhardy when 4,000 soldiers were camped in the Euphrates College. By remaining passive, they believed in the concept – “sacrifice a few for the sake of all”. They especially believed that this was the final crisis of the Turkish army and that empire would soon collapse at the hand of the victorious Allies. [48]

In the meantime, one of the priorities of the local authorities was to find the hidden caches of Armenian weapons. CUP inspectors arrived in Harput. Demands were made on arrested Armenians to hand over their arms. As we have seen, the procurement of arms by Armenians during the preceding years was not a secret. The local CUP leaders were well aware of what was going on. For instance they knew which local ARF leader was involved in the arms trade. The arming of Armenians reached its peak when the CUP and the ARF were allies and, in essence, was a defense mechanism against reactionary circles in the empire. In other words, and it may sound ironic, the weapons in Armenian hands were envisaged as a means to defend the constitutional order, and thus the state, from reactionary forces opposed to the 1908 revolution.

Conditions had changed, however. Arms caches were discovered one after the other. As was in the case in other Armenian populated towns, the uncovered firearms were transferred to the courtyard of the Municipality – Harput Municipality in this particular case. With the objective of making the “Armenian threat” more real, Ottoman Army rifles and bombs were added to the pile. This was all put on display for the Turks of Harput, and later, for those of Mamüretülaziz. Furthermore, under the supervision of the police, Mihran Tiutiunjian and Askanaz Soursourian, two of the Harput region’s Armenian photographers were escorted in to photograph this collection – the best evidence of treason. [49]

1) Donabed Lulejian; 1917, Garin/Erzurum

2) Donabed Lulejian; 1915 – Being treated in the Mezire Red Crescent Hospital after tortured in jail

3) Donabed Lulejian, 1916 - Photographed in Dersim

(Source: Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915 [in Armenian] Fresno, 1955)

It was during this time that Hovhannes Bujicanian and Donabed Lulejian were also arrested; the first on May 1 and the second in the beginning of June. Like countless other Armenians in the town of Harput, these two men were subject to terrible acts of torture while jailed. The two friends then found themselves in the same prison cell. In a trembling voice Bujicanian asks his friend, “Of course you were beaten for the Armenian letters procession.” Lulejian answers in the affirmative. It turns out that local Turks, especially members of the CUP, had harboured a three year hatred for the celebrations marking the creation of the Armenian alphabet and for its organizers. This pent up malice, jealousy and enmity would explode in 1915. Lulejian mentions an episode of his torture while in jail that reveals the mentality of the local CUP. Thus, he was paraded, bloodied and tortured, before a group of local Turks in the government building. He was rained with abuse and words of defamation. The municipality’s başkatip (chief secretary) approached Lulejian and said: “Teacher, how do you feel? Um? You’re good, very good. It’s the ABC celebration. Yeah! Don’t you remember?” Soon after, the acts of torture continue. The police pull his hair and pluck out his moustache. And the same başkatip and Anteblioğlu, one of his executioners, tell him: “It’s the ABC celebration. Make merry, teacher!” [50]

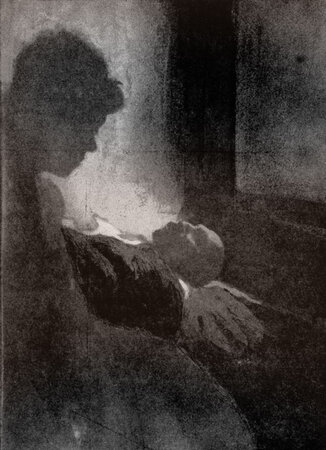

Despondent, disillusioned and unable to withstand further mistreatment, they attempted suicide in their prison cell. But they were physically incapable of this final act of desperation. Even assisting one another, suicide was beyond their means [51]. Later on, Bujicanian was transferred to the Kırmızı konak (red mansion) in Mamüretülaziz that had been converted into a prison. He would then been killed on the road of exile. As mentioned before, Lulejian was able to escape to Dersim where he wrote down his experiences. In the chapter describing the tortures he experience in jail, Lulejian, a pacifist and rational man who, till the end believed in the harmony between the various populations constituting the Empire, the reforming power of education and upbringing, struggles to explain in words the final fall and destruction of his world in Harput, which he had helped building.

“We progressed to suffer and to the extent that we strove for the highest level of education and integrity, the worse our torments became. The Turk exacerbated his disrespect towards us and focused his hatred against us.” [52]

- [1] A letter from H. Haroutyunian to Aram Andonian, December 17, 1908, Harput. Երկեր [Works of Tlgadintsi], Cilician Catholicosate press, Antelias, 1992, p. 293; K.H. Aznavourian, Արեւմտահայ գրողների նամականի [Letters of Western Armenian writers], Vol. VI, Edition I, Yerevan University Publishers, Yerevan, 1972, p. 28.

- [2] Hovhannes Bujicanian, «Տիպար քաղաքացին [Model Citizen]», Ամբողջական գործեր [Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works], Doniguian Press, Beirut, 1974, p. 355.

- [3] Hagop Gharib Shahbazian, Թանգարան գիւղը մեր եւ սիրոյ արիւնոտ ածուներ [Tadem Village and Bloody Love Gardens], France, 1967, p. 126.

- [4] This was the case in the villages of Habousi (present-day Ikizdemir), Pazmashen/Bizmişin (present-day Sarıçubuk), Körpe, Hogheh (present-day Yurtbaşı), Chorkegh (present-day Harmantepe), Morenig (present-day Çatalçeşme) and Komk (present-day Yenikapı).

- [5] www.houshamadyan.org/en/mapottomanempire/vilayetofmamuratulazizharput/harput-kaza/education-and-sport/schools-part-ii.html

- [6] Vahé Haig, Խարբերդ եւ անոր ոսկեղէն դաշտը [Kharpert and its Golden Plain], 1959, New York, pp. 346-347, 358-360, 365; Hapet Pilibosian (editor), Յիշատակարան Եփրատ գոլէճի, 1878-1915 [Memoranda of Euphrates College, 1878-1915], Boston, 1942, p. 124.

- [7] Born in Harput in1864, killed in 1915. Pilibosian, Memoirs of Euphrates College, pp. 132, 147-149; Nazaret Piranian, Խարբերդի եղեռնը [The Holocaust of Kharpert], Baykar Printers, Boston, 1937, pp. 46-48. Levon Lulejian recounts in his memoirs that in 1911 an Ottoman educational inspector is present at the year-end exams at Euphrates College and expresses his amazement regarding the students’ excellent knowledge of Turkish language and grammatical laws. The inspector pays particular praise to Nigoghos Tenekejian, who was also a Turkish language teacher. (Levon G. Lulejian, Days of Terror in Kharpert (1914-1915) [unpublished memoirs], Translated by Sevag Yaralian, p. 19).

- [8] «Եփրատի սաներուն [To the pupils of Euphrates]» April, 1910, in Հասկաքաղ Բրօֆ. Տ.Կ. Լիւլէճեանի (Բագրատ). գրական վաստակը եւ 1915-ի բանտի յուշերը [Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works and Prison Memoirs of 1915], Crown Printing, Fresno, 1955, p. 115.

- [9] Ibid. p. 117.

- [10] G.H. Aharonian (editor), Hussenig, Hairenik Printers, Boston, 1965, p. 74; Յուշարձան ուսուցչապետ Բենիամին Ժամկոչեանի [Memorial to head teacher Peniamin Jamngochian], Yerevan, 2010, pp. 151, 162; Vahé Haig, Kharpert and its Golden Plain, p. 688; Հապուսի գիւղին պատմութիւնը [The History of the Habousi Village], Baykar Printers, Boston, 1963, p. 26; “Vartanank”: A work of the Armenian writer Smpad Pyurad (born in Zeytun in 1862, killed in 1915).

- [11] Vahé Haig, Kharpert and its Golden Plain, p. 624; Jizmedjian, Kharpert and its Children, p. 391; Abdal Kolej Boghosian, Բազմաշէնի ընդարձակ պատմութիւնը [Comprehensive History of Pazmashen], Baykar Printers, Boston, 1930, p. 189; Arsen Gidour (editor), Պատմութիւն Ս.Դ. Հնչակեան Կուսակցութեան, 1887-1963 [History of the Social Democrat Hnchak Party, 1887-1963], Vol. 2, Shirag Printers, Beirut, 1963, p. 383. Henchag Party prominent activist Paramaz (Mateos Sarkisian, 1863-1915) settled in the town of Harput for a short time in 1911. As for ARF activists, the names of Vartan Shahbaz (1864-1959), Khachadour Bonapartian, Parsegh Shahbaz (1883-1915) and Sepasdatsi Mourad (1874-1918) are mentioned.

- [12] «Կարծիքի ազատութիւն [Freedom of Opinion]» (May 10, 1912) in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 219.

- [13] “Prison Memoirs, 1915” in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, p. 361.

- [14] «Ամերիկահայ ուսանողի պարտականութիւնը [The Obligation of an American-Armenian Student]» [in Armenian] (1910) in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, p. 122.

- [15] Ibid.

- [16] Respectively, the creator of the Armenian alphabet and the Armenian Catholicos of the era (5th c.)

- [17] Jizmedjian, Kharpert and its Children, pp. 413-415; “Prison Memoirs, 1915” in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, pp. 363-363.

- [18] «Մեծ Յոբելեանին սիրտը [Heart of the Great Jubilee]» in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 182.

- [19] «Մամուլին ոյժը [Strength of the Press]» in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, p. 52.

- [20] «Սահմանադրութիւն եւ շատախօսութիւն [The Constitution and Verbiage]» (March 15, 1912, Harput) in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 207.

- [21] «Հանրային գումարումներ [Public Convocations]» (December 1, 1909) in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 212.

- [22] “Model Citizen” in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 361.

- [23] D.G. Lulejian, Ուսանողին գաղափարականը (Բանախօսութիւն մը, 1912-ին) [A Student Ideology (1912 lecture)], Yeprad Printers, Harput, 1913, p. 6 (the booklet is attached to another work – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Իվանճելին, Աքատեան սիրավէպ մը [Evangeline. A Tale of Acadie], translated by D.G. Lulejian, Yeprad Printers, Harput, 1913).

- [24] «Կարծիքի ազատութիւն [Freedom of Opinion]» (May 10, 1912) in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 218.

- [25] Ibid, pp. 218-219.

- [26] «Արեւելք ու Արեւմուտք [East and West]» in Hovhannes Bujicanian, Complete Works, p. 230.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] Ibid, p. 231.

- [29] “Prison Memoirs, 1915” in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, p. 374.

- [30] Hamit Bozarslan, Histoire de la Turquie: De l’empire à nos jours, Tallandier, Paris, 2013, pp. 273-278; Raymond Kévorkian, Le Génocide des Arméniens, Odile Jacob, Paris, 2006, pp. 241-259.

- [31] Bozarslan, Histoire de la Turquie, p. 276.

- [32] «Հ. Յ. Դաշնակցութեան վեցերորդ Ընդհանուր Ժողովին որոշումները [Decisions of the ARF Sixth World Congress]», Document 1542-37 in Նիւթեր Հ. Յ. Դաշնակցութեան պատմութեան համար [Materials on the History of the ARF], Vol. 9, Yervant Pamboukian (Ed.), Hamazkayin Press, Beirut, 2011, p. 126.

- [33] Janet Klein, The Margins of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 2011, p. 151.

- [34] Dikran Mesrob Kaligian, Armenian Organization and Ideology Under Ottoman Rule, 1908-1914, Transaction Publishers, New Jersey, 2011, p. 109.

- [35] Arsen Gidour, History of the S.D. Hnchak Party, p. 393; Boghosian, Comprehensive History of Pazmashen, p. 173; Gyuregh Khrayan, Ծովք-Կէօլճիւկ [Dzovk-Gölcük], Arara Printers, Marseille, 1927, p. 117; Kourken Mkhitarian, Մեր գիւղը Դատեմ [Our Village Tadem], Hairenik Printers, Boston, 1958, p. 65; Manoog B. Dzeron, Բարջանճ գիւղ, համայնապատում (1600-1937) [Parchanj village. Encyclopedia (1600-1937)], Boston, 1938, p. 188.

- [36] See on this issue: Klein, The Margins of Empire, էջ 152-169.

- [37] Hans-Lukas Kieser, “Réformes ottomanes et cohabitation entre chrétiens et kurdes (1839-1915)” in Etudes rurales, juillet-décembre 2010, 186, p. 54; Kaligian, Armenian Organization and Ideology, p. 60.

- [38] See: Kevork S. Yerevanian, Պատմութիւն Չարսանճագի հայոց [History of Charsanjak Armenians], G. Doniguian Printers, Beirut, 1956, pp. 416-440.

- [39] «Ազգային երեսփոխանական ժողովի ատենագրութիւններ, 21 Յուլիս 1911, Պոլիս [Transcripts of the National Parliamentary Assembly, July 21, 1911, Istanbul]» in Yerevanian, History of Charsanjak Armenians, p. 424; «Յիշատակագիր Հ. Յ. Դաշնակցութեան եւ “Իթթիհատ վէ Թերագգը“ կուսակցութիւններու փոխադարձ յարաբերութիւններու մասին [Memorandum on the ARF and Ittihat ve Terakki Parties’ Mutual Relations]» (Prepared according to the decision of the 6th World Congress), Document 78a-2 in Pamboukian (Ed.) Materials on the History of the ARF, p. 152 ; Haygazn K. Ghazarian, Պատմագիրք Չմշկածագի [History Book of Çemişgezek], Hamazkayin Press, Beirut, 1971, pp. 232-245; Kaligian, Armenian Organization and Ideology, p. 64.

- [40] “Memorandum on the ARF (…)” in Pamboukian (Ed.) Materials on the History of the ARF, p. 155; «Տեղեկագիր Լեռնասարի Կ. Կոմիտէին [Bulletin to the Lernasar Central Committee]» (Sent to the ARF 6th World Congress), Document 1534-11 in Pamboukian (Ed.) Materials on the History of the ARF, p. 331.

- [41] This Kurdish tribal rebellion intensified in April 1908, before the Young Turk revolution. The main reasons were state taxes and military conscription. Those who rebelled attacked area Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish villages. The tense situation and attacks continued even after the proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution. This is why local villagers took self-defensive measures. (I thank Cihangir Gündoğdu for this information).

- [42] Vahé Haig, Kharpert and its Golden Plain, p. 628.

- [43] Jizmedjian, Kharpert and its Children, p. 393; Boghosian, Comprehensive History of Pazmashen, pp. 190-192; Yerevanian, History of Charsanjak Armenians, p. 394; Mkhitarian, Our Village Tadem, p. 71; “Bulletin to the Lernasar Central Committee”, p. 329; Shahbazian, Tadem Village and Bloody Love Gardens, pp. 140-141; Vahé Haig, Kharpert and its Golden Plain, p. 628; Yerevanian, History of Charsanjak Armenians, p. 393; H. Adjemian (editor), Ուրոյն տեղագրութիւն Չմշկածագ գաւառի – Թումայ Մեզիրէ [Unique Report of Çemişgezek district – Touma Mezireh], No. 5 [unpublished], Boston, 1951, p. 7.

- [44] “Prison Memoirs, 1915” in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, p. 446.

- [45] Ibid., p. 403.

- [46] It is not known whether this secret meeting was held in the town of Harput or Mamüretülaziz.

- [47] “Prison Memoirs, 1915” in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, pp. 405; 428-434.

- [48] Ibid, p. 450. Also see: Vahé Haig, Kharpert and its Golden Plain, pp. 1417-1418.

- [49] Lulejian, Days of Terror in Kharpert (1914-1915), pp. 118-120.

- [50] “Prison Memoirs, 1915” in An Anthology of Prof. D.G. Lulejian Works, pp. 486, 488.

- [51] Ibid, p. 492, 504, 513.

- [52] Ibid, p. 405.