Memory book of Verin (Upper) Khokh

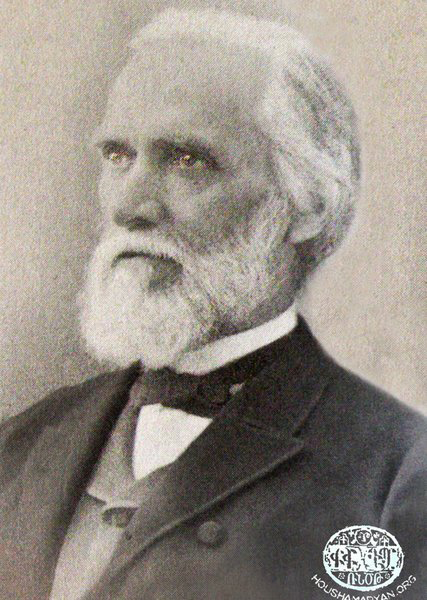

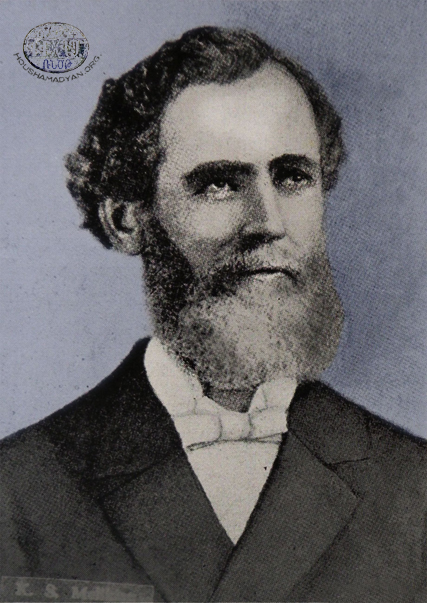

By Bagdasar Avedis Bagdasarian (1864-1934)

Editorial note

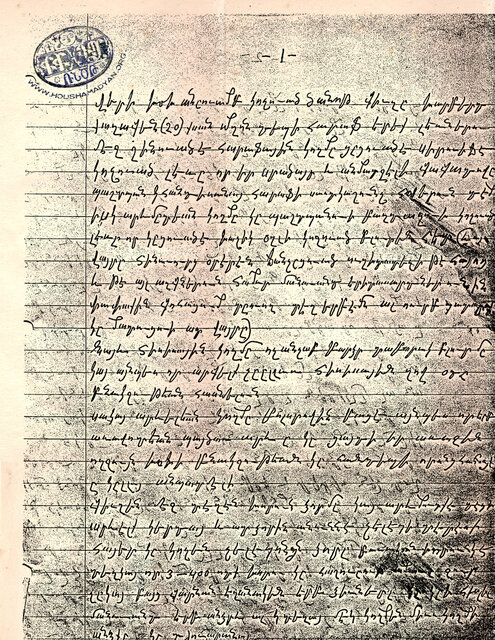

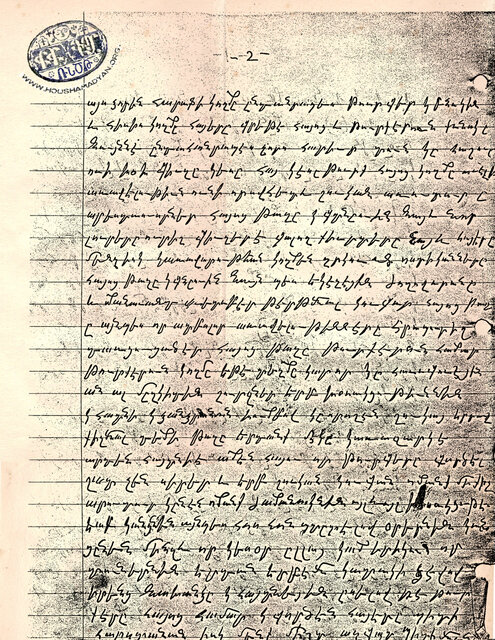

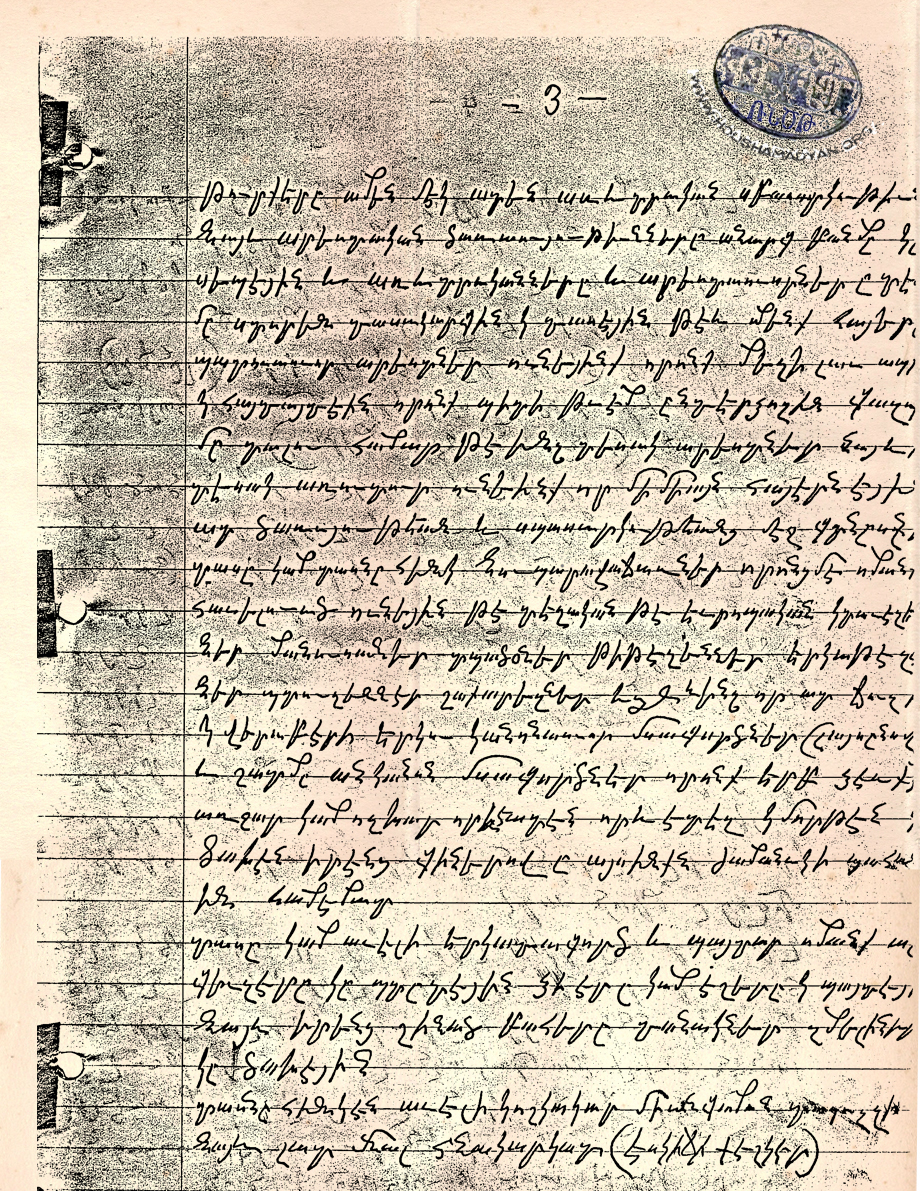

Bagdasar Bagdasarian was around 24 years old when, in 1888, he permanently left his village Verin Khokh (current name Deveyolu) and immigrated to the United States. He had been educated in the Armenian school of the village, which meant he never had the opportunity to study past primary school. He wrote in simple, conversational Armenian; his writing was rife with grammatical and dictation mistakes. At the same time, it is clear that Armenian was the language in which he could express himself most comfortably.

Most would be discouraged from embarking on a writing project if they hadn’t yet mastered a language, or couldn’t write without making mistakes. But Bagdasar Bagdasarian ignored this hurdle, and in the process left us a memory book of about a hundred pages, in which he tells the story of Verin Khokh until the time he left it.

We present here his Armenian original with only minor changes. The main intervention is the correction of dictation mistakes—but not always. When, for example, the misspelling is a product of the local dialect (in this case, that of Kharpert/Harput), we have kept it as is, as when he wrote “haraf” instead of “harav” (south). We have also introduced punctuation in many places, as the author rarely employed punctuation marks. Apart from these minor changes, however, we have kept the phraseology and grammatical structure of the text unchanged, by and large, in order to preserve the author’s language and conversational writing style.

Why did Bagdasar Bagdasarian pen this work, given his difficulties with the written language? We believe this question ought to be addressed to the entire generation that lived in the newly formed, post-genocide diaspora. The pain of loss, the longing and the demand for justice prompted hundreds, if not thousands, from that generation to pick up their pen and write about their ancestral home, village, or city. Without these feelings, the authors would not have embarked on reconstructing a past life with the soaring enthusiasm and diligence that define their work.

Indeed, it was vital for someone to pen the story of Verin Khokh, as the Armenian population of the village was annihilated, and Armenian life there destroyed forever. It was under such conditions that the likes of Bagdasar Bagdasarian became their village or town historian, the memoirist. And herein lies one of the most invaluable features of the book: Without Bagdasar Bagdasarian’s effort, the history of this location, once populated by Armenians, would have been lost forever. We find very little information in published books about Verin Khokh; only bits and pieces of information are available in the voluminous books about the Kharpert/Harput region written by Vahé Haig and Manug Djizmedjian. [1] Bagdasarian wrote this unpublished work in Fresno in the 1930’s, shortly before his passing.

Many memory books about villages and towns remain unpublished in family archives. That was the case with Bagdasarian’s work. We have decided to provide space on our website to these unpublished memory books, and are hopeful that visitors will send us the unpublished memoirs, letters, and notes from their own family archives. We are committed to working on these writings and making them publicly available.

Bagdasar Bagdasarian’s text, although riddled with literary shortcomings, demonstrates the author’s sharp analytical skills, as he explains the village’s social structure and fabric, the interactions between the local Armenians and Turks, the rule of the village begs (chieftains) in the absence of the state, the evolution of the relationship between the local chieftains and the state, etc.

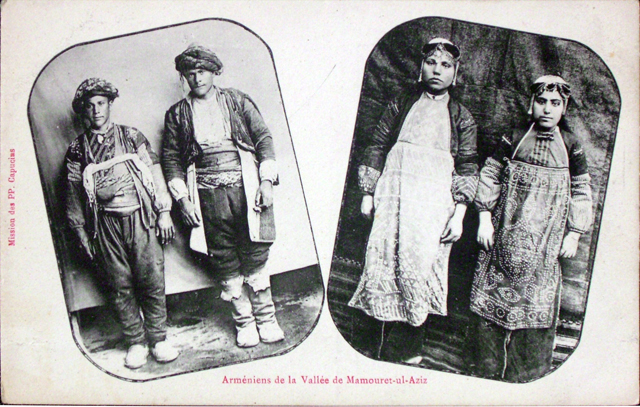

Oral history commands a significant place in this book. The author had heard many of the details from the village elders, be they Turks or Armenians. Although exact dates are not known, it is clear that they pertain to developments in the 18th and 19th centuries. The village chieftains had such a profound impact on village life that its history is a sequence of noteworthy events that took place during the reign of this or that chieftain—as if they were kings. Here’s a listing of village chieftains: Aleh beg, Zilfo beg, Mamo beg, Asaf agha… Their rule over the Armenian and Turkish population of the village was unchallenged. There were also other overlords controlling swaths of land in the village, and were referred to as uşak/ushakh (servants of the chieftain). Armenian peasants were the marabas (sharecroppers) of the begs and aghas: The land they tilled belonged to the agha, but the cropper received part of the harvest. Bagdasarian details the gradual strengthening of the state’s authority over the village, whereby the Armenians were liberated from their maraba status. He emphasizes, however, that these changes had their downside, and they were not necessarily beneficial to the Armenian villager.

Of particular interest is the participation, as volunteers, of some of the village’s Armenians in the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). Bagdasarian also provides interesting details about the arrival of Protestantism in the village. Quite often, he witnessed first-hand the events he recounts.

As in many other memory books, clichés like “laziness,” “brutality,” and “deceit” are associated with Turks. Such terminology could sometimes be the product of post-genocide influences. Nevertheless, they do not undermine the true value of Bagdasarian’s work. We believe that through the micro-history of Verin Khokh, he sheds light on the history of the relations between Armenians and Turks.

The chronology of the book ends on the threshold of the 1895 massacres, when Bagdasar Bagdasarian immigrated to the United States. During the anti-Armenians violence of Sultan Abdulhamid, Verin Khokh bore the brunt of the bloodshed that plagued the Kharpert region. More than 100 Armenians were killed. Afterwards, the majority of the population of Verin Khokh moved to Mezire (Mamuretülaziz/Elazığ), Kharpert, or immigrated to the United States. Before the Armenian Genocide of 1915, the Armenian population of the village had shrunk to 40 families. [2]

We present below the first 25 pages of the 100-page memory book. The remaining pages will be posted in the coming weeks.

[1] Vahé Haig, Խարբերդ եւ անոր ոսկեղէն դաշտը. Յուշամատեան պատմական մշակութային եւ ազգագրական [Kharberd/Harput and its Golden Plain: Historic, Cultural and Ethnographic Memory Book], New York, 1959, 1500pp; Manug Djizmedjian, Խարբերդ եւ իր զաւակները [Kharberd/Harput and its Sons], Fresno-California, 1955, 751pp.

[2] Djizmedjian, pp. 338-339

Plain of Harput/Kharpert with its Armenian towns and villages. The Aradzani River (Eastern Euphrates, Murat River) appears as it flows today, after a number of dams altered its original course. Map prepared by George Aghjayan and reworked by Houshamadyan.

Present-day names: 1|Kavakpınar; 2|Kavakaltı; 3|Elmapınarı; 4|Saraybaşı; 5|Kuşluyazı; 6|Alpağut; 7|Ayıbağ Koy; 8|Obuz; 9|Sarıçubuk; 10|Cöteli; 11|Harmantepe; 12|Hazar; 13|Güzelyalı; 14|Uzuntarla; 15|Korucu; 16|Yedigöze; 17|Ikizdemir; 18|Yolüstü; 19|Örençay; 20|Yurtbaşı; 21|Ulukent; 22|İçme; 23|Karşıbağ; 24|Güntaşı; 25|Kızılay; 26|Harput; 27|Dedeyolu; 28|Kavaktepe; 29|Şahinkaya; 30|Kıraç; 31|Gurbet Mezre; 32|Gümüşkavak; 33|Kuyulu; 34|Yenikapı; 35|Konakalmaz; 36|Körpe; 37|Elazig; 38|Mollakendi; 39|Çatalçeşme; 40|Munzuroğlu; 41|Yünlüce; 42|Bağlarca; 43|Akçakiraz; 44|Saray; 45|Sarıkamış; 46|Çağlar; 47|Güngören; 48|Bahçekapı; 49|Aşağı Bağ; 50|Yukarı Bağ; 51|Olgunlar; 52|Tadım; 53|Doğankuş; 54|Yazıkonak; 55|Kuşhane; 56|Sinan; 57|Virane Mezre; 58|Aksaray; 59|Yeneci; 60|Altınçevre; 61|Değirmenönü; 62|Muratcık; 63|Çakıl; 64|Kaplıkaya; 65|Erbildi; 66|Salkaya; 67|Igopkoy; 68|Çakmaközü; 69|Dallıca

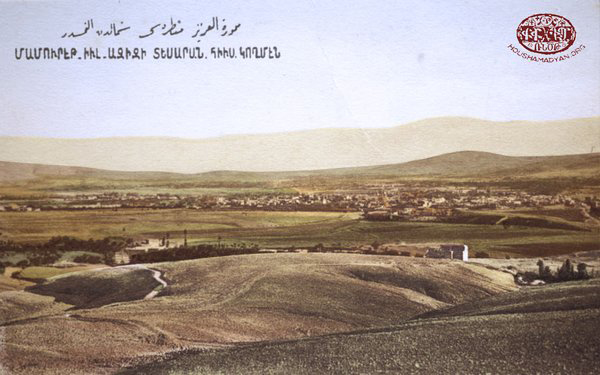

Memory book of Verin Khokh (present-day Dedeyolu)

[page 1] My native village of Upper Khokh was located approximately twenty miles south of the city of Kharpert/Harput. The village sat between three mountains. On the southern side stood a mountain called Servidjeh. Its pointed and unique summit protected the village from the wild winds of winter. The village was protected on its west side by a mountain called Paghtajough, which connected to a hill named Khatchig Oghli. On the northern side there was a smaller hill with a flatter summit that eased the northern cool winds as they reached the village. On the eastern side the land was open and clear. The residents of Khokh thoroughly enjoyed basking in the first rays of the morning sunrise. From ancient times Armenians and others visited this area for pilgrimage. Holy Mass was often conducted here. The area was also popular to visit for recreation, especially by young people.

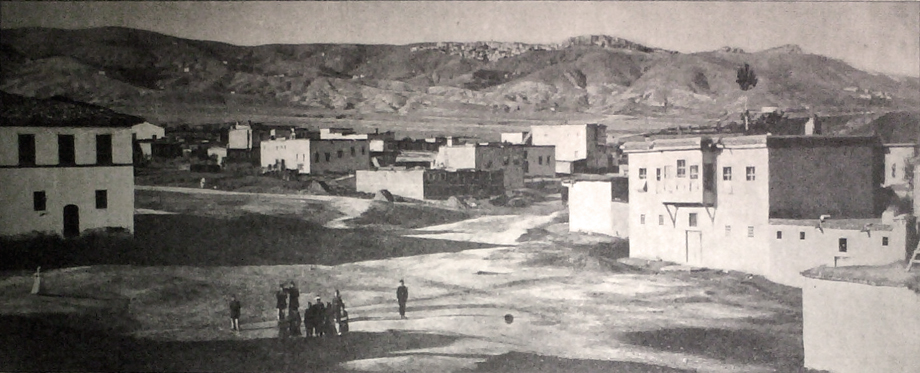

Panorama photo taken from Lake Dzovk/Gölcük (Source: Vahé Haig, Kharpert/Harput and its Golden Plain: Historic, Cultural and Ethnographic Memory Book, New York, 1959. [in Armenian])

In the middle of the village was a deep canyon expanding from west to east that the Turks named Chelebi Deresi, but the Armenians called it Chelebi Gorge. The canyon was 300 to 400 feet deep. In the summer there was no water, but in the spring season when the snow melted, and particularly when it rained, the crossing from one side to the other became very difficult. [page 2] The Turks lived on the south side of Chelebi Gorge and the Armenians lived on the north side. The population of Turks and Armenians was about equal. The village of Khokh consisted of approximately 400 families, half Armenian and half Turkish. The Armenian side was better because the markets, businesses, and professional artisans were all located there. Kurds and Armenians from different villages and Turkish government workers and officers would often visit our village. The Armenian church and the Armenian protestant temple were also located in that side of the village. The Armenian neighborhood received a journal called Avedaper. All these factors made the Armenian neighborhood attractive to the Turks of the village.

Pages from the Bagdasar Bagdasarian manuscript about the history of his village.

The Turks often congregated to visit and converse around their Mosque in Lower Khokh. Sometimes they would come in groups to the Armenian side for shopping. It was clear to the Armenians that the Turks did not enjoy working. When they came to the Armenian side they shopped a little and engaged in conversations until the day was over and then returned to their homes. Though jealous of the Armenians’ success, [page 3] the Turks considered our business and retail operations demeaning and considered the artisans and business owners as the lower class. But the Armenians had honorable jobs and businesses that supported us comfortably.

The Armenians of Upper Khokh were actively involved in business and commerce. There were ten to fifteen grocery store owners. Some of these grocers also owned other businesses that sold local and European fabrics, prints, tins, metals, sweets, fruits, and other products. There were two licensed butchers, although there were also some illegal butchers who would kill a cow or a lamb anywhere on the road and price the meat according to the market demand. There were ten or more blacksmiths and farriers who installed horse shoes on donkeys and horses and sold their handmade shovels, knives and razors. There were fifteen or more shoemakers, shoe repairmen, and leather tanners. There were more than fifteen tailors who had their own shops, and some who would work for others. [page 4] There were fifteen or more bricklayers and ten saddle-makers (çulci and semerci). There were three barbers, one of them a Turk, and one who sharpened knives and razors (kılıççı). There were three carpet weavers. There was a bakery (or sometimes more than one), and two master tiners (copper plate cleaners) (kalaycı). There were also eight businesses that produced bulgur and wheat. Their mills would sort bulgur into fine and coarser grinds. One of these workers was a Turk. There were also four carpenters (najar).

Fabric spinning and weaving was done in both Turkish and Armenian households. The Turks kept their fabric weaving for their own personal use, but the Armenians sold their fine finished fabrics to the Kurds who inhabited the surrounding villages. This was a moneymaker for many Armenians in the village.

Four stone mills to grind grains were located a mile away from the village. Although the mills belonged to the Turks, the millers were Armenian. Twenty or more businesses existed for carding cotton and approximately the same number existed for separating the cotton from the husk by using a machine called djerdjer. There were six, or more, shepherds, most of them Turks.

Ten or more villagers were vineyard guards, most of whom were Turks. [page 5] There were 30 farmers, 5 drum players (davulcu), the same number or more horn players (zurnaci). There were also peddlers, shoe repairmen, and knife sharpeners, who traveled to nearby villages on the foothills surrounding Khokh to sell their goods and services. Most of the inhabitants of these nearby villages were Kurds. There were more than 200 Kurdish villages on the mountains, while at the base of the mountains there were big and small villages.

The Kurds of these nearby villages also engaged in trade in Khokh. In addition to buying products and services from the Khokh villagers, they sold their own products. Their products included wheat, rye, corn, barley, cows, ewes, goats, sheep, lambs, chickens, eggs, cheese, butter, and vegetables. These products were often traded for spun cotton and woven fabrics. Summer or winter, the village almost always had a busy atmosphere. The village turned into kind of a city when the Kurds came to the village. The Kurds never came empty-handed; they always brought something to sell, even wood, tree branches, and oak twigs, [page 6] which the Armenians had use for. Thus, the things that the Kurds brought were always useful and everything was sold for high or low prices. In trade and commerce, we needed the Kurds and they needed us.

A general view of the village of Verin Khokh (present-day Dedeyolu) (Source: Vahé Haig, Kharpert/Harput and its Golden Plain: Historic, Cultural and Ethnographic Memory Book, New York, 1959. [in Armenian])

I described to you the location of the Khokh village, which was almost enclosed by three mountains. Khokh had its specific roads, although it did not have a main avenue. From the west there was a road that led to the Armenian neighborhood that reached the main market. From the north, there was another street that also led to the main market through the Armenian neighborhood and then straight to the Turkish neighborhood. From the east, there was another road which also led to the market. From the southern side, a road wound around the mountain and also ended in the Turkish neighborhood. The roads were poorly designed with no survey methods used.

A question arises: how is it that this important village was hidden between the mentioned mountains? If the village of Khokh had been constructed one mile east, it would have been possible to build a proper town on the existing vast plain. Although a lot of rocks were arranged around the edges of the fields there, none of the elders knew or told us anything about it.

Some of our village elders explained the history of Khokh. [page 7] An old village was situated two miles northeast of where Khokh is now located. To the east of the old village was a big mountain by the name of Mother Mariam. On the south side of Mother Marian was a taller mountain named Saint Stepanos. Also next to the old village's water source on the northeast side, you could see a hill resembling a Turkish fez (a traditional Turkish hat). The hill displayed unique soil colors that were not seen anywhere in or around the area. No one could say for sure how or why this hill was erected. One story was that the Prince who ruled the land many years ago ordered his subjects each to carry a bag of soil to see how big a mound could be built. Others said that the hill was used during emergencies when a fire would be lit on the top of the hill to summon help from other nearby villages. Another story [page 8] was that the hill was used to sacrifice animals for religious ceremonies.

Varin Khokh (present-day Kavaktepe): A general view (Source: Vahé Haig, Kharpert/Harput and its Golden Plain: Historic, Cultural and Ethnographic Memory Book, New York, 1959. [in Armenian])

The old village’s water source, a spring, was at its center, and it was surrounded by fields. The borders of the fields were identified by stones and fences which were erected all around the corners. In some areas rocks were piled in an irregular pattern, but all the fields were divided in one square mile partitions. It is my opinion the old village was much larger than an American section of land (consisting of one square mile).

The church and cemetery were located one mile southeast of the old village. We still used the old village’s cemetery and called it the Lower Cemetery. Many considered the cemetery to be sacred because of the presence of the church ruins on the site. As such, most people would not consider the Upper Cemetery fit for the burial of their loved ones. [page 9]

The water spring I mentioned above was a water source for a mill. The water was extraordinarily cold and so when we visited the spring, the village where we stayed ceased to be attractive. When we were young, our teachers took us to the fields to eat mulberries in the summer; they considered this to be a sort of recreation. We used to sit at the source of the spring with our teacher, who would regret being deprived of that water and of the beautiful scenery. Our elders repeated stories they had heard from their elders to the effect that our forefathers were not to blame for deserting the fertile lands surrounding this water source and migrating to the nearby foothills that were dry and arid.

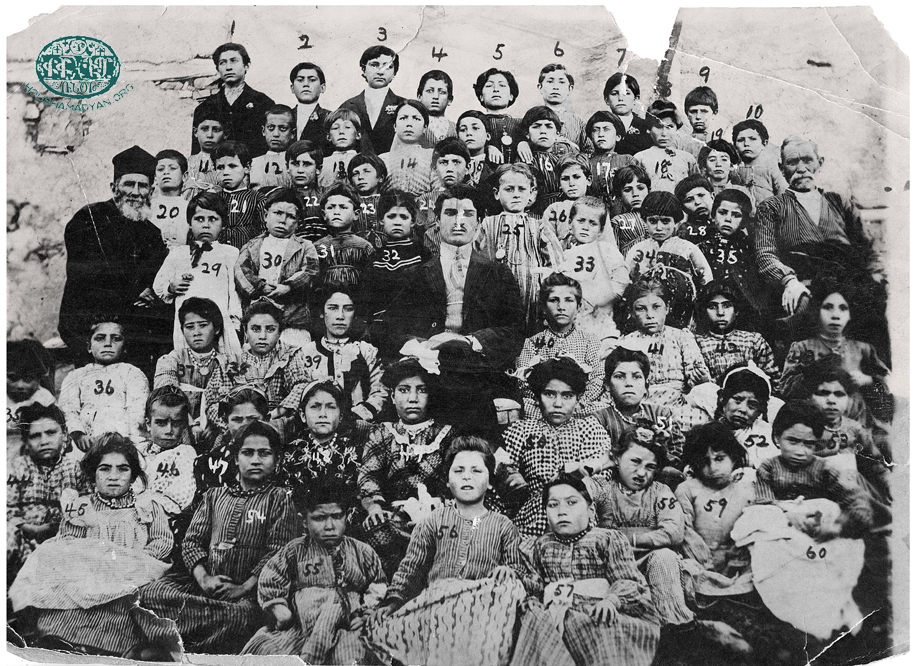

Hovagim Baghdasarian’s family from the village of Verin (Upper) Khokh. Hovagim was the uncle (father’s brother) of Bagdasar Bagdasarian, the author of the manuscript/memory book about Verin Khokh. Most likely, Hovagim is the man seated in the left side of the photo. Hovagim is a major figure in Bagdasar’s manuscript (Source: Vahé Haig, Kharpert/Harput and its Golden Plain: Historic, Cultural and Ethnographic Memory Book, New York, 1959. [in Armenian])

I learned the history of the old village and the settlement of Khokh from the elders. Uncle Kevork Der Zakarents, who was one of the landowners, told us a lot about the history. Khatadji Yaghub also talked about the history, as he was the eldest of the village. [page 10] Yaghub used to say that his father remembered the buildings of the old village, and according to him this was a history of a hundred and fifty years at that time. Also, my own uncle would tell similar stories about the old village history that he had heard from elders. Many Turks also told very interesting stories that were not contradictory to the other stories we heard. According to the local oral history, the old village’s population was close to five hundred inhabitants. Approximately one quarter were Armenians and the rest were Turks. The ruler of the old village was a Turk by the name of Aleh Beg, who ruled with great experience and authority. The village was ruled through a monarchical system, as Turks cannot be governed by any other system. The village was built on a big avenue, and as such the inhabitants were constantly subjected to calamities; since many Tatars traveled towards the south. These undesired travelers would attack, hurt and brutalize the peaceful villagers, thus making life miserable for the village. The villagers would fight these cruel Tatars and Mongols many times, but sometimes they had to give in to the unjust demands [page 11] of these invaders when they were large in numbers.

When the situation became unbearable, the villagers approached their ruler Aleh Beg to find a way to end their suffering at the hands of these hoodlums. They requested that they relocate their village to the Servidjeh mountain foothills, where they would be protected by thick vegetation and be surrounded by three mountains with no access roads for the Tatars and Mongols to invade. The only drawback was the presence of a gorge on the eastern side, but they maintained that the gorge could be easily protected. They argued that when Tatars or other invaders were seen, the villagers could gather as guarding soldiers at the eastern side of the gorge. They could protect the village by throwing stones from the high mountain and also in other ways, forcing the Tatars to escape and sometimes even leave behind dead bodies. Although the villagers were right and their demand was righteous, Aleh Beg, as the defender of his people and as their leader, did not want to abandon the old village and allow it to lie in ruins. Aleh Beg thought that it would be possible [page 12] to restrain those invaders through force. It was said that sometimes there were hundreds of Tatars who invaded the village armed with the latest weapons. These Tatars would use the element of surprise to bring a lot of damage and harm to the peaceful villagers. There were more demands made, but Aleh Beg considered the ruin and abandonment of the old village as treason. His only answer remained, “Let them see, I only do this for your benefit.”

These troubles continued for years, gradually increasing, with the difficulties multiplying. The people persisted in their request, but Aleh Beg refused to change his mind. He believed that if the people abandoned the old village they would face more suffering and misery and that he would be responsible. Although his relatives were initially on his side, they seemed to gradually change their minds because the situation in the village was becoming unbearable. However, Aleh Beg’s answer remained: “I work for your benefit, wait and times will change,” etc. It is true that times changed, but for the worse.

Then a new ruler appeared by the name of Zilfo Beg, who brought some of the villagers under his rule and started a fight with Aleh Beg [page 13]. Thus, there were now enemies on the inside, Zilfo’s followers, and enemies on the outside, the Tatars. Zilfo Beg did not have the power to topple the kingdom of Aleh Beg, so he waited for the right moment. That moment soon came. There was an incident that changed the course of events, which offered a favorable solution to both sides.

One hot summer night, the son of Aleh Beg, whose name was Mamo Beg, heard horses approaching and went outside to investigate. Five Tatar invaders abducted twenty-year-old Mamo Beg, tied him to a horse and sped away in the darkness of night. Neither his father nor the servants witnessed the abduction. The murderers took Mamo Beg seven miles south to Gölbaşı and imprisoned him in a deserted mill barn [page 14]. They beat and tortured Mamo Beg to the point that he begged them to kill him and put an end to his suffering and misery. The murderers refused and said that a message will be sent to Aleh Beg and that he will be captured and beaten as well.

The young man, despite his pain and suffering, thought fast to save himself from his abductors. He fabricated a story that his real father and Aleh Beg were blood enemies and that Aleh Beg would reward the abductors for injuring Mamo so seriously.

Gurgho Gurghoyian, who ran the water mill in Verin Khokh, and his family. They were all killed in 1915 (Source: Vahé Haig, Kharpert/Harput and its Golden Plain: Historic, Cultural and Ethnographic Memory Book, New York, 1959. [in Armenian])

One of the ”intelligent” members of the group [page 15] suggested that they go to Aleh Beg’s house and tell him about their bravery and how they tortured and injured the son of his enemy. “Aleh Beg will certainly reward us and we’ll then have the chance to kidnap the Beg.” They all agreed to this wise suggestion. On their way to Aleh Beg’s palace, Mamo talked to the abductors very politely and told them of ways to kill Aleh Beg and get rid of his whole dynasty. When this happened, he explained, his father would become the new leader and all of these Tatars would be richly rewarded. The Tatar murderers, feeling remorse for torturing the young man, decided not to hand him over to Aleh Beg. When they arrived at the old village, Mamo showed them a building and told them it was his house. The Tatars went straight to the Beg’s palace. They tied their horses to the posts and entered the building. In the meantime, Mamo explained the events to Aleh Beg and disappeared inside the palace. The murderers, not knowing that Aleh Beg was the young man’s father, were escorted in and they told Aleh Beg their stories in detail, with some exaggeration, of how much they had tortured his enemy's son and would kill the young man upon his orders. Aleh Beg slyly asked why they hadn’t killed the young man [page 16] or why they had not brought him to Beg so that Beg could kill him himself. The Tatars replied by saying that he was going to die anyway, and that they wanted him to suffer some more before he died. They also asked Aleh Beg to name his enemies, one by one, and said that they would murder them all. Aleh Beg, with a fake smile on his face, expressed his pleasure and assured them that they would be rewarded monetarily, that they would become his bodyguards, that they would sit with him at the table, that they would marry the daughters of his relatives, and that they would get many other rewards beyond their imagination. They were then offered private rooms for rest and relaxation. Aleh Beg promptly had the murderers beheaded. The “rest” he offered was eternal rest.

Aleh Beg was a good and experienced politician and sensed that this action on his part would cause retribution by the Tatars and cost him dearly. So he decided to give way to the people’s request. He summoned the village announcer to spread the news to the inhabitants to be ready to relocate to the new site by morning. [page 17] Armenians called the new site "Khokh" and the Turks called it "Khookh.” The new location of the village was previously used as a summer holiday spot. It is very probable that they built small cottages there - the word cottage is believed to bear the meaning of a hut and as such is probably in Armenian. Zulfi Beg opposed the decision to relocate the village. However Aleh Beg’s decision was irrevocable. “If nobody comes, I go and I take my family with me, this is my decision,” said the Beg. The majority of the villagers followed Aleh Beg to the new land, but approximately one hundred stayed behind with Zulfi Beg.

Without the protection of Aleh Beg, the followers of Zulfi Beg were unable to build their homes on the main road of the old village, so they decided to relocate next to Aleh Beg’s followers, one mile north from the old village and on the road half a mile to the east. The settlers following Aleh Beg named their village Upper Khokh (Yukarı Khokh) [present-day Dedeyolu] and the settlers following Zulfi Beg named their village Lower Khokh (Aşağı Khokh) [present-day Kavaktepe]. The Armenians went to the Upper Khokh together.

[page 18] The reign of Aleh Beg was too harsh and dominant. As we saw during our lifetimes, the Turks of Upper Khokh were like slaves for the aghas and were scared of them. In contrast, the Turks in Lower Khokh were considered as equals to the aghas and acted boldly with them. In Lower Khokh there were five to seven aghas (rulers) and in Upper Kokh there were thirty to forty aghas who were the servants (uşak) of Aleh Beg, and they were very proud of this association. In my honest opinion, Lower Khokh Turks were of a higher class and were treated better than Upper Khokh Turks.

As I have mentioned, this story that I have heard is a one hundred and fifty year old story; it’s the story of seven or eight generations that has been passed on orally. All these stories from our elders are supported by evidence, although we are unaware of some details. Both the Turks and the Armenians in the village of Khokh used to tell about [page 19] the statecraft of Aleh Beg with great interest and admiration. They used to call him the father of the village because of his providence and popularity. They said that he never used to take sides, and that he would protect the rights of both the Armenians and the Turks.

When the new village's boundary was drawn, the first task was to keep the Turks separate from the Armenians. As I said earlier, the new village of Khokh was divided by a gorge called the Chelebi Gorge. To the south of the gorge was the Turkish section and to the north was where the Armenians lived. This division was a smart move on Aleh Beg’s part. Each section had its own water source. I have to add that there were better and colder water springs outside of our village. Because we were not introduced to the concept of pipes, they had made a few wells near the village and managed to connect them to the market neighborhood. This caused lots of mishaps. Overall, the Turkish section had better water quality. There was a water fountain, but the location of the spring source was kept a secret from the public. Part of that water ran next to the Mosque, and as such it was called the Cami (Djami) spring. [page 20] The water ran to the aghas’ mansions (konak) too. They used as much as they pleased and the rest was dumped down the Chelebi Gorge. Not one plant or flower or vegetable was planted on Turkish property. This comes to prove how lazy and insipid the Turks were in general.

Aleh Beg’s’ mansion was next to the Mosque and right in the middle of the Turkish quarters. The other aghas’ mansions were built next to one another on the side of Chelebi Gorge in a very picturesque setting at the highest point in the village. The new generations continued in their footsteps. These were of great pride to Aleh Beg and of the servants. However, in time they overbuilt and there was no more space left to build on. Some were forced to build their konaks at the foot of the mountain, others passed through the valley to the northern part, and others built in the common Turkish neighborhoods. Also some forty common Turkish families passed the valley and lived in the southwest section of the Armenian neighborhood.

Fresno, January 1906: The Baghdasarian family. (From left): Varteni (née Rahanian), Zaruhi, Bagdasar, Avedis. In the photo, Varteni is pregnant. She would later give birth to Beniamin, who in turn would become the father of Marvin Baxter, who wrote the preface to this page (Source: Baxter family collection)

There were also some Armenian families on the other side of the valley who had settled in the Turkish side. Those Armenians were farmers by profession; the neighborhoods in which they settled had great privileges for farmers. [page 21] They called it Lower Quarters and both Armenians and Turks lived together. These houses were next to each other, and the rooftops were bridged together. From three to eight families lived under one common roof. During the summer season they built huts which served as bedrooms.

Because they lived together, we can assume that the Turks and the Armenians of these neighborhoods were closer and got along better with each other, and indeed this is what we saw. Occasionally, the sword and the hatred would surface and the power of the aghas always played a major political role. Sometimes hatred and sometimes love and peace determined the relations between the two groups, based on what the aghas wanted. It was obvious that the aghas were more sympathetic to the Armenian folks inhabiting the Lower Quarters, for they took a responsible role in the maintenance and care of the agha lands and crops. Armenians often worked in the aghas’ homes, although the aghas sometimes paid indirectly. As such the Armenians of the Lower Quarters had gained the admiration of the Turks and the aghas. When a Turk commoner bothered any Armenian who was a farmer, the agha would pitilessly beat this Turk, and as such the farmer felt much safer. At the same time, the aghas also protected their own workers and craftsmen. They called them emektar –old and faithful servant- and didn’t have the habit of changing their servants.

I remember when the aghas said that [page 22] three generations of Turks and Armenians coexisted together. “This or that Armenian tradesmen served us with loyalty, and we rewarded the Armenians financially and also provided them with protection.“

The history of Verin Khokh. Complete handwritten pages.

Aleh Beg, with his savvy entrepreneurial vision, established new shops and businesses in the Kharpert/Harput town market area to provide rental income to the elderly. The servants (uşak) of Aleh Beg appreciated and praised him as a smart businessman and considered this his greatest achievement. No one knew how many shops there were or the amount of rent they generated as income to the servants of Aleh Beg. Only Aleh Beg’s uşaks knew and they never shared their secret with anyone. The elderly aghas not only praised him, but prayed for their beneficiary’s soul as well. The younger servants who were next in line to receive the rental income would pray for the elders to die, so their turn would come to collect the income generated from the rentals. Only males had the right to collect the rent, never the female servants.

[page 23] The Aleh Beg uşaks owned a lot of land, and some of them still do. These are lands which they inherited from Aleh Beg. Some owned thousands of cheregs [a form of measure, as acres] of land, some less, but even the poorest agha owned at least a hundred chereg of land. They usually gave their lands to maraba peasants. The agha provided the seeds while the maraba would plough and reap with their oxen. The maraba workers would transport the rick, would thrash the wheat and clean it; they would share the wheat, lentil, barley, grass and even the hay equally with the agha.

The farms were located in or near Upper Khokh [present-day Kavaktepe], Lower Khokh [Dedeyolu], Churchapor, Alinjugh, Shentil [Bahçekapı], Ichme, Elemlig, Akhor [Saraybaşı], Khalfa, Khavaz, Hisolar, Balan, Khatunkev, Beyrdzagh, Lotoghli, Gaban, and Guney.

Aleh Beg supposedly governed an area of approximately fifty miles or more. It was a small sovereignty in which he resembled a feudal lord (derebey). There was an unwritten law in Khokh which required local residents to pay a fee to the oldest agha in order to be permitted to build a house in or around the village. Another unwritten law provided that it was forbidden to sell a foothill or mountain vineyard located between two properties owned by different aghas. [page 24] Aghas could have a vineyard at any time and on any mountain, but common Turks could not. These mountains served as a pasture for the cattle and sheep. Any villager was allowed to graze his cattle and sheep there.

In the olden times prior to my birth, only Aleh Beg’s servants could buy land. Except for their homes, which they could build or buy, Armenians and common Turks could not purchase real property. During my lifetime, however, both Armenians and common Turks bought and sold real estate.

It is known that Turks are addicted to gambling. Even earlier, gambling was their leisure activity. Some aghas lost their lands, vineyards and mills to common Turks because of gambling. As a result, some common Turks were wealthier than the privileged begs.

Brothers Zilfo Beg and Aleh Beg were aghas who lost their wealth. They lost their fortune to a common Turk named Isak Agha, who was the son of Esef Agha. Isak Agha became rich through gambling.

When I lived in Upper Khokh, Aleh Beg was richer than all the other aghas and took advantage of his servants by foreclosing on properties they used as security for loans from him. [page 25] Aleh Beg gave as many loans as were requested and when the time came for these debts to be paid, instead of taking the money, Aleh Beg bought lands from them by adding a small amount on top of the initial loan. He became so wealthy that he controlled the village. It was as though he had monopolized the governance (müdir) of the village. Nevertheless, Aleh Beg’s servants did not respect the two brothers and spoke of them, behind their backs, in degrading terms.

In old times, chieftains and derebeys ruled various regions which belonged to the Ottoman Empire in a monarchical manner. Likewise, Aleh Beg ruled Khokh as his small kingdom. The central government authorized such governance.

I described Aleh Beg’s diplomacy and his administrative abilities earlier; he always tried to protect his subjects’ interests without endangering his own personal interest. There was a proper prison where his servants would work as jandarmas (1). [page 26] Just as in the case of kings, the authority to rule was passed from father to son. This unwritten fact is ratified through evidence. Aleh Beg built the Upper Khokh village; he put all in order, grew old and passed away. He was thus succeeded by his son, Memo Beg. When Memo Beg came to power, people believed that he was neither better nor worse than his father. They said, “The son of a wolf is a wolf.” Some Armenians and Turks obeyed Memo Beg, not because they were afraid of him but because they loved him. Sometimes the Turkish people praised him and told many stories about his life that they had heard from their elders. After Memo Beg passed away, the successor aghas or begs who ruled achieved nothing significant. After a couple of decades, a dictator by the name of Esef Agha came to power and ruled with an iron fist. Those who had seen him or had been punished by him [page 27] said that he was much meaner than his predecessors. He was a tyrant who terrorized and punished the residents; his name spread terror among people. Esef Agha built a big and secure prison equipped with chains and all kinds of torturing devices to punish criminals. Those criminals who were hard to control were killed. He was both the judge and the executioner. He would often force heavy fines on criminals (such as tobacco, cattle, horses, goats, oil, cheese, and whatever he could get). He would be most happy when he would receive red gold coins as a fine. When the offense was not as serious, he would force the prisoners to work on his farms. If any prisoner tried to escape from prison, he would only be saved from death by god’s help or through some miracle. Even when the criminal activity occurred outside his jurisdiction, sometimes twenty or more miles away, he would summon his guards to arrest and bring the criminals to him for judgment. Murderers, burglars, robbers, and female abductors were brought to him. The criminals were freed if they paid a bribe or agreed to give him most of what they would steal in the future.

[page 28] When I lived in Khokh, there were many people still alive who had been punished by Esef Agha during his reign, while others had benefited from his generosity. Some were subjected to cruelty, others saw mercy. It was believed that he sent his servants to see if people were poor and whether they at least had clothes to wear. He helped those in need; he didn’t want to see his subjects live in poverty. One of his servants who was still alive said that as a reward for being a loyal servant for twenty years, the Agha had given him a piece of land. Many said that Esef Agha punished the bad and rewarded the good.

Esef Agha was the wealthiest man in his day. Many of the lands, vineyards, and mills that we knew belonged to him. But Isak Agha, Esef Agha’s son, gambled and squandered away his father’s properties. His caretaker, who was Armenian, urged Isak to be more responsible and not to gamble away his father’s hard-earned money. [page 29] The caretaker advised and sometimes reprimanded him, saying: “If you continue in this manner, you will also debase your deceased father’s name, you would bring disgrace.” Isak didn’t appreciate the criticism and threatened to replace the caretaker if it was repeated. One day the caretaker heard from the harem that Isak Agha intended to replace him. He didn’t want to lose his job so he continued to serve loyally by carrying out the tasks of making sure people gave him what he ordered: wheat, oil, a few sheep, money, etc. He served until Isak could no longer afford to hire any servants. The caretaker and his peers saw how he ran out of money and was deprived of everything. Isak Agha believed himself to be lucky and hoped to secure the position of a şahne (2) every year, but failed. I remember, as if it were yesterday, that when Isak Agha was called to occupy a şahne position, he was very happy and attributed this to Allah’s mercy. Isak Agha died in 1886, two years before I emigrated to America. His lands, vineyards, and mills were already passed on to Ali Beg and Zilfo Beg.

[page 30] I would like to write about another one of Esef Beg’s smart arrangements. My uncle is a big and important part of this story.

My uncle told us this story about Esef Agha, which my uncle witnessed during his lifetime. Esef Agha was one of Aleh Beg’s servants. The Agha’s relatives grew larger and larger in number and although he was the ruler of the village and its surroundings, he had trouble punishing his relatives who treated the Armenian population unfairly and deprived them of their rights. Thus the Armenians complained to Esef Agha, who naturally did not punish his relatives for the sake of the Armenians. Esef Agha met with all his relatives and instructed all of Aleh Beg’s servants to leave the Armenian villagers alone because they were humble people and good workers. He told them the Armenians would have full protection during his reign and that there would be no such disorder. To prove his point, he took approximately sixty Armenian families under his wing and instructed every agha to do the same. They registered a document of aghas “sponsoring” Armenian families, which to this day is kept in Zilfo Beg’s mansion. They divided the Armenian families beween them like sheep or cattle [page 31], where every Turkish agha would have his raya (3), and every Armenian would have a Turkish agha as a protector or guardian. The Armenians were instructed to contact their guardian if extra security was needed for their protection.

My uncle told us that at times fights erupted between the aghas who were trying to defend their Armenian rayas’ rights. It was the agha’s responsibility to protect his Armenian subject, and it was the Armenian’s responsibility to serve his guardian agha. For example, when it was time to prune the agha’s vineyard and to plough the field, the Armenian was called to do the job. When it was time to plant watermelons, to cut the grass, to grind bulgur, to carry out minor household tasks, again, it was the Armenian who was called to do the job. The Armenians carried out these tasks without complaining. One or two Armenians from each household would devote two to three weeks a year serving the aghas. As such, their dues were considered paid. In the meantime, the aghas gradually grew lazy. These aghas would summon an Armenian or a Turkish clown to entertain them by telling jokes. They would sometimes curse these entertainers, call them funny names and laugh. [page 32] There was also another pastime for these aghas. Among themselves, they would praise their Armenian servants and would talk in competitive terms of who had a better and more talented servant. The subject of conversation varied from the servant’s physique to his wealth and qualities which gave pride to the aghas. This created jealousy and hate amongst the aghas, who would sometimes exchange their servants: Garabed for Hovhaness, for example.

Sometimes an agha would give an Armenian family to another as a present during a Muslim holiday (bayram) or for marriage. Such stories were the topic of everyday conversation. After reading this, the reader might assume that these were times of total slavery.

I will also present the other side of life in those days. I will mention the names of the wealthy and well-to-do people who lived in Khokh. There has been no other time period in Khokh’s history during which there have been so many wealthy familities as during Esef Agha’s reign. [page 33] The following are the names of the rich people during those days; many people still attest to this while the remnants of their wealth remain as evidence: Yaghoub – blacksmith and merchant; Kotan Aved – blacksmith; Chalegh Elo or Arzuman– blacksmith; Der Zakar – tiller and shepherd; Murad – blacksmith; Topal Minas – tiller; Kino – tiller and shepherd; Gulesser – weaver. There were many other Armenians who had made small fortunes, who were prosperous, and led good and comfortable lifestyles.

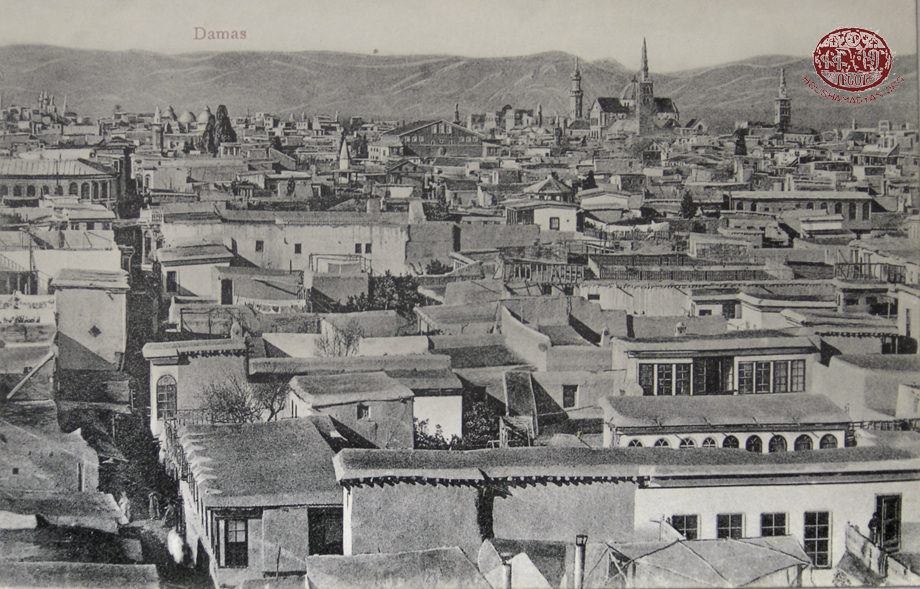

Mghdes Baghdo became a legendary Armenian merchant in Khokh and in the whole of Kharpert/Harput area. Around 1754, there was a flood in the village of Dzovk/Gölcük. Part of the population built houses at the foot of the mountain, around a valley (although the flood reached their homes). While the majority of people flooded dispersed to the city of Kharpert and in surrounding villages, Khokh also received some of those displaced. Among the newcomers was a fifteen-year-old orphan [page 34] whose name was Baghdasar Choulkhashian. The young boy became an apprentice in the Yacubian blacksmith shop in Khokh. The owner, Master Yacub, took Baghdasar under his wing and treated him as his own son. The young boy showed respect to his adoptive family and became interested in learning the business. Anyone who entered the Yacoub workshop would assume that the boy was a family member. Master Yacub saw the talent of a merchant in this young man and trusted him with more business responsibilities. Eventually, both of Yacub’s sons and the other employees worked under this young man's guidance when he was appointed to the most responsible position in the business. In time, Baghdasar and Master Yacub’s family became closer and closer and came to love each other dearly. Baghdasar and Yacub’s daughter, Badaskhan, fell in love, and with the master’s blessing a wedding took place very quickly. As a token of his approval and as his daughter’s dowry, Yacub built a house next to his and invited the newlywed couple to reside there [page 35]. Master Yacub also gave them a large sum of money so they could go to Jerusalem for a pilgrimage and visit the holy sites. He estimated the trip would take at least two years. Thus, the mules were set and each was given a horse, everyone wished them a safe journey and the couple was bid farewell. Mr. and Mrs. Choulkhashian accepted the gift with pleasure and went on their trip. They visited different parts of Palestine; they also visited Aleppo and Damascus. In the two-year time period, they got acquainted with business owners and tradesmen. They returned home with big plans for the future.

Upon approaching Khokh, a big crowd of Armenians and Turks came to greet and welcome them back. They welcomed rich Yacub’s daughter and son-in-law with big festivities; The couple in turn gave gifts to the villagers. Master Yacub’s son-in-law became a well-known personality and became known as “Mghdes Baghdo [Mghdes/Mahdesi is a name given to people who do pilgrimage to Jerusalem].

[page 36] Master Yacub, who was growing older, eventually gave his store to Mghdes Baghdo and his workshop to his sons. Yacub forgave the money people owed him on contracts (which amounted up to a few thousand pounds). He burned all of them and instructed his children and his son-in-law to never take money from the clients if they tried to repay their forgiven debt; “The wealth I leave to you today is accumulated thanks to the clients.” Mghdes Baghdo continued the business with no interruptions, made a lot of friends, and later converted the store into a large business office. He became a father to five sons and one daughter. One son was highly educated and handled all the accounting of the business. The other sons also occupied important positions in the business. He imported a variety of goods, mainly embroidered fabrics from Aleppo and Damascus for which he had the wholesale rights. He owned forty mules and employed his own mules and coachmen to transport the goods. Mghdes Baghdo imported herds of goats, cows, and lambs from Bingöl and Erzurum and sold them to the residents of Kharpert and its surrounding areas. These were used to make khavurma (4) and were sold in cash or on credit.

[page 37] Mghdes Baghdo’s fame spread not only in Kharpert, but to other states as well. His grandson and friends told stories about how he led his caravan of mules, which was guided by a peşenk (5), while riding on his Arabian horse. As soon as the aghas heard the news that Baghdo was arriving, Esef Agha would lead all the other aghas, and they would travel halfway to meet and greet him. They would all get off their horses and hug one another and Esef Agha would welcome him home. Mghdes Baghdo always brought valuable gifts to the aghas, but the most valuable gift was always for Esef Agha, who was Baghdo’s protector and guardian of his wealth and family.

In those days, only the servants of Aleh Beg had the right to have double doors, but Mghdes Baghdo was given the right to have one. Mghdes Baghdo’s eldest son and his children had seen the double doors, which existed until the year of the massacres, during which the Turks burned the houses of all the Armenians in the village, and these double doors burned too.

[page 38] Mghdes Baghdo conducted his business for forty years, but in his old age he encountered major losses. News spread that sheep were dying of diseases in Erzurum and only five hundred sheep were driven safely to Kharpert, and not in the best of health. Thus, these sickly sheep were of no use. Mghdes stayed strong facing these adversities, and recommended to his children that they be strong too, but then he heard that his mules and the goods they carried were stolen by an Arab gang of thieves and that his son Sarkis barely escaped death; luckily the bullet had gone through his hat, not his head. Some men had escaped and were saved, but many others were killed and there were many injured. Upon hearing this news, Mghdes became very discouraged and apoplectic. Days later Sarkis returned and told him how it all happened. Hearing this, Mghdes became very angry. One of his friends from Lower Khokh invited Mghdes to his house so he could relax and forget about his troubles. However, Mghdes Baghdo couldn’t bear the strain and passed away within a week. Within 40 days of hearing the news about the attack on the caravan, Mghdes Baghdo was dead.

[page 39] Several Kharpert businessmen, who traded with Mghdes Baghdo, asked his sons to continue the business, but the sons declined. Instead, each of the five established his own separate business: butcher, baker, çerçi (peddler), bakkal (grocer). They each already had their businesses; the merchants promised material support and asked them again, but they still declined, fearing that the Arab gang of thieves would attack again.

All the businesses founded by Mghdes Baghdo’s sons were limited. Altough his grandchildren and great-grandchildren all lived on income from the businesses and through trade, they all lived on limited means. It is true that the majority of the Khokh residents were merchants and craftsmen, but there was no one else like Mghdes Baghdo or Master Yacub – not in Khokh and not even in Kharpert! I leave it to the reader to judge whether it was the circumstances of the time that enhanced their success in business or if these men truly had a great talent. It is also for the reader to judge whether the condition of the Armenians during the time of the raya system was better, or whether it was better when the government ruled (6). The above-mentioned ruling system was only during Esef Agha’s reign. Although Zilfo Beg came to power after Esef Agha, it was the central government that took control during his time.

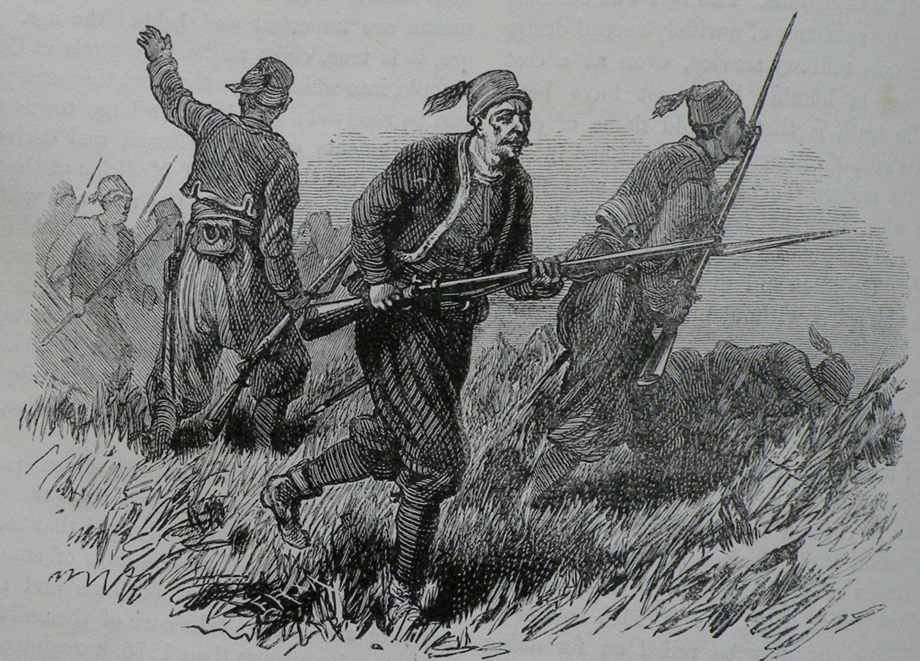

[page 40] My apologies for digressing and including the following story: During Sultan Mahmud’s reign (7), the Ottoman government had adopted a policy to eliminate the feudal lord system. When chieftains, brigand chiefs, and other rulers were in power, they all ruled independently and they all exploited the system. The followers of one chief would attack the other chieftain; one would win the other would lose. Especially within Kurdish circles, people may have heard the names of Bedirkhan Bey (8) and Khan Mahmud, who were leaders of very big tribes. Thirty miles south of our village lived a different race of people, who were called Jello, and who ruled almost like kings in the south of the river Euphrates. Raşid Pasha (9) attacked and conquered villages with cannons and a forty-thousand-man army. He killed women and children mercilessly. He also attacked the head ruler of the Kurdish village, a man named Tarkho, who ruled the Kurds from the northern part of the Euphrates to Merhimit. Tarkho wanted to help the Jello tribe, but had the same fate as the Jello people. Another tribe called the Kelbiko and others ruling the Hafta mountain chain were attacked and subdued by another Pasha called Haci Izzet. [page 41] The barbaric nature of the Turk’s aggression and violence was well known to all of us. I heard from eyewitnesses that they were offered very low-priced goods to buy that had been stolen during the attacks. Even Haci Izzet Pasha had asked these eyewitnesses to purchase at very low prices cattle, horses, and other personal property stolen during the attacks. One of those who bought stolen property was my boss. As hard as they tried to remove the crooked chiefs from power, there were still many more thugs and tribe’s chiefs around to cause harm to the villagers.

Reforms were always promised, from Istanbul and at all levels of government, saying that the Ottoman Empire would soon be modernized like the European countries. During the days of Sultan Abd-ul-Mejid (10) and Sultan Abdülaziz (11), hopes that democratic rule would alter the government brought excitement among the young, who would embrace the dream of happier days ahead. The hope for change was on the horizon, especially since people saw that corrupt chiefs were actually being captured and punished. Thus, the youth believed themselves to be lucky since they were born during those times.

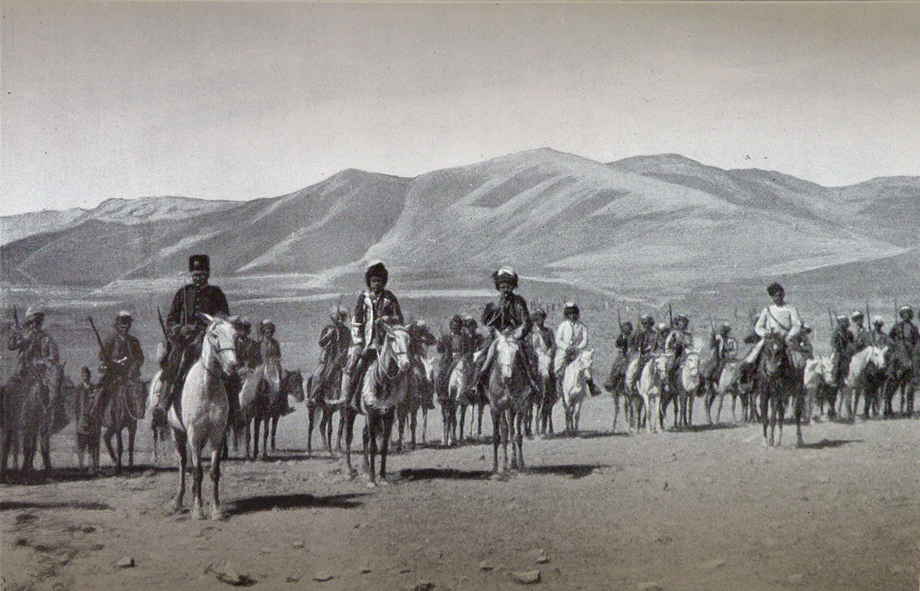

When Sultan Hamid (12) took over power, all of a sudden [page 42] the thugs and corrupt chiefs, who were hiding from the limelight, surfaced again. The Kurdish tribes became more organized like the Hamidiye cavalry (13) and came under the direction of Kasim Beg or Mussa Beg. The two had their differences, but their common goal was to attack the Armenian population by robbing and vandalizing them. Kurds were not considered the only aggressors. Turks surpassed the Kurds in more heinous attacks against the Armenians. Armenians asked for government intervention. Unfortunately, the government did not take notice and encouraged more attacks on them.

At that time there was a war brewing between the Turks and the Russians. The Armenians were looked upon as if they were the instigators of the war between the two countries and, as a form of punishment for this, the Armenian-Christians were singled-out for burdensome new taxes. Armenians did not feel safe to travel to other villages in order to work to be able to pay the unjustly high taxes levied on them. Every new day would bring another unjustified law to punish the Armenians. Most Armenians did not have the courage to even go to their own vineyards to pick up the fruit of their labor. Stories of old happy days when the aghas were in power were often told and the elderly longed for those days.

A few of the Armenians would approach the influential aghas they knew to ask for protection. With a foxy and sinister smile on their faces, the aghas would deny protection to the Armenians, saying that times had changed. [page 43] In the village, we had some Armenians who were very strong but who were only capable of defending themselves. The Turks didn’t touch these Armenians and when they talked to them, the Turks were careful to use civilized language. They knew that if they dared touch them, things would end badly for them. Here are the names of those who were capable of defending themselves: Krikor Garabedian (Kakere), Mahtesi Khayo Arzman, Parsekh Parossian, Baghdasar Minassian, Mardiros Minassian, Melkon Boyadjian, and a few others whom we’ll meet through the stories to follow.

In 1876, robberies and vandalism were common occurrences. Turks were using different types of keys, machines, and tools to break into our homes and businesses to steal our property. Many other ugly events threatened the security of the Armenians, who without despair, would often travel to the government center of Mezire [14] to complain and request help, all to no avail. Their voices were not heard. On the contrary more misery was implemented.

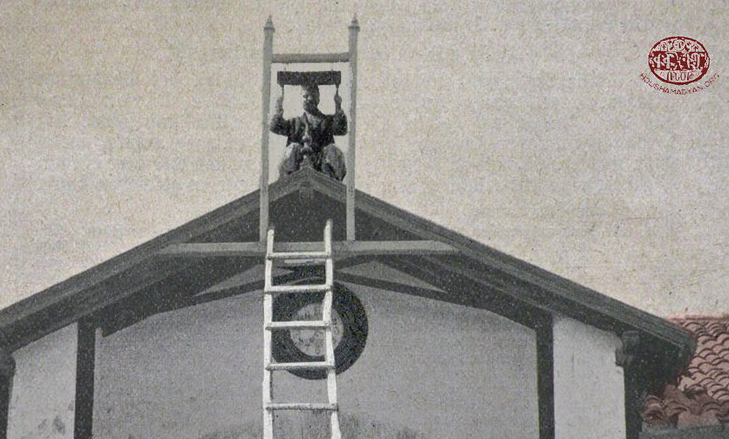

The aghas summoned both the Apostolic and the Protestant Armenian elders together for a meeting to warn them against the chiming of the gochnags [i.e., a wooden device used to invite believers to church] before their church services. They told the Armenians to put an end to this obsession. One Protestant Armenian named Krikor countered that the Muslim Mulla cleric had the freedom to preach loudly five times a day. The Turks got irritated [page 44] by that comparison and started beating the poor fellow. They told him that because he was poor, the punishment would not be as severe; whereas if he had been a well-known or wealthy person, his punishment would have been much more severe. Krikor was grateful to the Lord that he was a poor fellow so his punishment was mild and no thieves would rob his house. Or so he thought! He was wrong. While he was away, a thief went to his house and stole all his belongings. Both congregations disregarded the warning and continued to conduct their church services with the ringing of the church gochnags, which made the aghas’ threats even more severe. They told the Armenians that if the aghas heard the sound of church gochnags ringing, the sound of the Armenians’ begging to stop the violence would not be heard! They told the Armenians to think it over and reminded them that they were responsible and had to choose.

The elders of both congregations met and after a long discussion decided to discontinue the ringing of the gochnags, thereby giving way to the Turks’ unjust demand. Nevertheless, the gochnags of the Apostolic Church and their hammers were stolen by the Turks. One of the church trustees by the name of Kevork Angdjugian complained to the aghas, saying that it was a mean act to steal church relics, especially after the Armenians had obeyed by stopping the ringing of the church gochnags. The aghas promised to return the gochnags and, sure enough, the gochnags were found and returned. A few days later, Kevork was found badly beaten. Unfortunately, he never recovered from this attack and died the following year. [page 45] The latest threat and the beating of brother Kevork stopped the ringing of the gochnags for good and both churches conducted mass in silence.

The security of the Armenians and their properties was not guaranteed even after all those changes that took place. Turks found any excuse to fight and hurt an Armenian at every opportunity. The Turks would openly shout: "Only three days left.

Armenians were not able to bring their own fruit crops of grapes or pears home; it was the Turks who enjoyed the fruit of Armenian hard labor. Once in a while some young Armenian men would go to their vineyards trying not to be seen, just as if they were burglars, but often they were caught by the Turks who hid by the side of the roads, who grabbed the fruits, smashed them and then beat the Armenians. Thus, the Armenians never dared to go back again and their vineyards were left to the Turks.

The Armenians held another meeting and decided to go to Mezire again to complain. Led by the priest, the protestant reverend, members of the apostolic and protestant congregtions, the Armenian aghas, the chief of the village (kocabaşı), and some fifty Armenian protesters went to the Pasha to explain that it was not possible for the Armenians to live in Khokh anymore and asked him to find another location for them to move [page 46]. In the month of September, on a Thursday, a much bigger crowd than previously selected congregated to walk behind the protestant minister and the priest. When they reached Mezire, they looked for and found Goshgar Mardiros, who was an Upper Khokh resident but lived and had his own business in Mezire at that time. This man had connections in the government circles and as such he led the delegation. Because Friday is a day of rest for the Muslims, the Armenian delegation waited until Saturday to present their written complaint. They had to wait till Monday to hear the outcome. Everyone stayed in Mezire on Sunday.

That same Sunday, a missionary by the name of Mr. Wheeler (15) visited Upper Khokh’s Protestant church to preach. Before his sermon he requested the ringing of the gochnags. The congregation explained to him that the Turks had forbidden it. Upon hearing that response, he insisted that they ring the gochnags and accepted all the consequences that might come from the angry Turks. Many of the reverends there were hesitant, while a young man by the name of Boghos Yaghubian dared to make the gochnags be heard.

Yaghubian rang the gochnags with a hammer longer and harder than normal. The sound of the gochnags was unmistakably heard by the Turks, who immediately sent two Turkish spies to the church to see what was happening. The spies met a [page 47] “non-believer wearing a hat” (şapkalı gavur) [the American missionary] and were intimidated by the sight of this foreigner as much as the Armenians were intimidated by the Turks. The aghas were informed of this, so they sent more spies to find out when the missionary would leave. The Turks waited until the missionary left for the village of Khuylu [Telgadin/Kuyulu] on his horse. When they were sure that the missionary was gone, that same night the aghas decided to burn down the Protestant church, especially since they knew that around fifty Armenians were out of town, as they had gone to Mezire to complain. They were aware of this because, unfortunately, some Armenians had the habit of telling all our secrets to the enemy. The naive Protestant parishioners, in a good mood after the ringing of the gochnags, did not know the fate awaiting their church.

Sunday after midnight, Mghdes Khayo’s dog began barking nonstop, so he stepped outside carrying his gun to investigate. He saw several people congregated in front of his house. He asked them in Turkish who they were and what they wanted. The head Turk, who was called Khallo, reassured him that they did not intend to harm him [page 48], but that they were planning to burn down the Protestant church and told him that he could join them if he wanted to.

Mghdes Khayo, who was hot tempered and bold, began firing his gun. The Turks, who did not have any guns, started throwing stones. Most of the Armenian villagers, who were sleeping on their roofs, joined the fight. Some even came to help from lower neighborhoods. The Turks fled to the west side and continued to throw stones from a higher position. There were more Armenians than Turks, but the Turks were on higher ground and we all knew that at the end the Turks would win the fight. I witnessed this fight and saw the rocks hurling down at great speed. One of the stones broke Bedros Baghdassarian’s wood stick and hit Aznavur Garabedian’s right arm and shattered his elbow. Aznavur, who was a good fighter, was taken out of the fighting area. Mahdesi Hovhannes Arzumanian was fighting and yelling encouraging words to the Armenian fighters. He yelled: "Armenians, those are a couple of untrained lads and it would be a shame if we lost this fight; do not despair, we are with you, [page 49] let’s run uphill and capture them."

The Armenians, while cursing the Turks, ran up the hill to higher ground and chased the Turks away. Unfortunately, the Armenians thought the fight was finished and ordered their youth to return to their homes. The Turks started a new attack from the north side, cursing the Armenians and throwing rocks down the hill. Armenians followed suit and threw stones back at them. No one was injured in this fight except Aznavur, who had to stay home to recuperate for a couple of weeks.

At three o'clock that morning, three aghas from Khokh rode in on their horses to investigate the incident, acting as if they were not already aware of the situation. The Armenians explained their side of the story. The great Zilfo Beg ordered our people down from their roofs and reprimanded them for the fight as unnecessary between neighbors. [page 50] The Armenians made it clear to the aghas that they were not the aggressors and that they were attacked at night by the mob while they were asleep. The Armenians led the aghas to where the attackers were hiding. Zilfo Beg was surprised when he came face to face with his younger son. He was so angry that he spat on his son's face and scolded him, saying: “Ahmed, your face should turn black from shame!" After reprimanding his son some more, he ordered him to go home. Some believed he scolded his son because they were unable to carry out the task of burning down the church while others believed he was really unaware of the situation. The fight was over and the Turks were ordered to return to their homes. The Turkish hoodlums bragged about holding their own in the fight though outnumbered [page 51], while the Armenians remained silent, following their elders’ instructions. This fight helped unify the Armenians, though we never had any structure.

Collectively, the Armenians contributed all the expenses of a group to go to the government hall to place complaints. As a response to the complaints, and as in the past, the Turkish government officials promised to send employees to investigate the matters, but at the same time they unofficially advised the Armenian protesters to act responsibly and use restraint during warlike situations, to try to coexist peacefully with the neighbors, and to let go of such small matters. Upon hearing this advice, the Armenian delegation returned like a defeated army with no accomplished results. Later, when asked about the outcome of their complaint, the Armenians always answered that the government promised to send a team of officials to follow up on the complaint very soon. Sadly, they themselves did not believe that officials would actually come to investigate and find a solution for the problem. [page 52] However, within a couple of weeks two Turkish inspectors arrived in Khokh and requested a meeting with Zilfo Beg and the Armenian elders with the presence of Turks who were all members of the Elders’ Council. One of the inspectors asked the Armenians about the issues that had been bothering the Armenian community in general and how they could assist them in solving the problems they faced. An Armenian replied: “Sir, our homes have been vandalized, our walls drilled, our properties stolen, our security compromised, and our relatives have been beaten and dishonored.” The other inspector asked if they could name the criminals or how the latter could be restrained. An Armenian elder replied that it was unwise to name them because the gang activity would not cease and these baldırıçıplak (rough) criminals would commit those unlawful acts again and boast about their lawlessness with no fear. The Armenian continued by saying that the aghas and begs of their village were men of intellectual ability, but regretted the fact that they were not capable of securing their neighbor Armenians’ safety against these hoodlums. He continued to say that we always looked upon Aleh Beg’s men with respect. He said that the Armenians believed that if our aghas took on the burden of using their influence to intervene, [page 53] then none of the disturbances would happen and we could be protected just as before, when the aghas were in power and the Armenians were safe: “We have always thanked the aghas for their protection and thank them still; and it is true that we have also benefitted from the agha’s servants before. We believe that we could be safe if only the aghas would implement their power. Our estimable government surely uses all means to ensure the safety of the residents of its villages and states.” The speaker then thanked those present and sat down. The inspectors asked more questions. It was as if they occupied the position of mediators, rather than that of official inspectors. Thus the Armenians could not expect much, but regained hope when one of the aghas started speaking. The aghas accepted our compliments and positive suggestions, but also complained a little. They were critical about the big changes in the Turkish government. They said that times had changed, that it was not easy to govern the Turkish people. They said they didn’t deny protecting us and our deceased forefathers. They said that only a few weeks previous, when some hooligans [page 54] had tried to bother the Armenians, they had intervened and used their influence to put an end to the aggression, and sent those hooligans home after advising them not to repeat their offenses. They said they didn’t have armies or weapons but had always tried and would always try to help their neighbors. Sometimes the governmental officers themselves made mistakes and failed in their duties, but that doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t help.

The Inspector asked the aghas to work harder to achieve peace in the village. He said: “This will bring respect for the aghas. Soon the conditions will change and the villages will have local councils (müdürlük) whose members will be the locals. Aghas, I hope we didn’t come here for nothing.” Turning to the Armenians, he asked them to be more patient and assured them that very soon better days were on the horizon. The Armenians bowed and left the meeting with little hope or expectation.

In the following months some lifestyle changes occurred. The looting and robberies continued, but were considerably less, and sometime the aghas found the criminals and recovered the stolen goods. Other times, they could not help. Armenians were allowed to go to their fields to tend the crops. Also, they walked freely in the Turkish neighborhoods with no fear [page 55]. Foreign church missionaries, Rev. Crosby H. Wheeler and Rev. Herman Barnum (16), who were notified of the restriction against ringing the church gochnags, finally convinced the government officials to reverse that law. The aghas passed the good news to us and showed regret about the initial restriction, which had come from Mezire. They told us that now we had the right to hear the church gochnags ring again, an order that also came from Mezire. This was the aghas’ good news. They changed their attitude a little and showed some sympathy. The Armenians took this sympathy into consideration, but were still skeptical – they wondered where this sympathy came from and how long it would last. No one was able to answer these questions.

The government in Mezire made different demands on the Armenians. They demanded [after the start of the Russo-Turkish war, 1877-1878] extra monetary contributions to purchase supplies for the army and, another time, demanded ten mules. They also asked for three Armenian volunteers to join the Turkish Army or to raise the sum of one hundred and eighty kaimes (17) in the village instead. There were three young men who volunteered to join the Turkish army ranks. This event had a big impact on the Turkish neighbors and on the aghas. I will later elaborate a bit more and tell some interesting stories about our Armenian volunteers and their tricks.

[page 56] The Russo-Turkish war ended with the defeat of the Turkish army. Peace was expected to follow, and people hoped to live a tranquil life. Although the living conditions eased, the prediction of more peaceful days for the future proved incorrect. Out of the approximately 130 young Turks who were recruited into the Turkish army, only about half returned to their homes. These returning soldiers felt more experienced and enlightened, having seen other countries, and thus felt more independent.

The young men were somewhat disobedient but still did not dare to totally rebel. Later one of the aghas, who was not a servant (uşak) of Aleh Beg, encouraged these young soldiers to revolt. The first to rebel against the aghas was a young man by the name of Shekir. Shekir got into a fight with Agha Khalil in the middle of the Armenian neighborhood. Khalil and his brother attacked Shekir and hit his head several times and let him lie on the floor in front of dozens of onlookers. They ordered people not to interfere until Shekir was fully punished. No one dared to speak, and Shekir returned to his house injured. The other baldırıçıplak (barefoot thugs) Turks heard about this but, because they were not organized, they said nothing. When a turbulent, quarrelsome Turk by the name of Khallo, [page 57] who was Shekir’s friend, heard about the fight and heard that Khalil had beaten Shekir, he said, in front of other Turks, that if they dared to do the same to him, he would kill Khalil and his brother. Khalil heard about this threat and took action.

The two brothers went to Khallo’s workplace accompanied by other Turkish friends. Khallo and his coworkers were in the middle of preparing mud to make bricks. Khalil ordered Khallo to approach them. While approaching Khalil and his men, Khallo told his friends to watch what he was going to do. Khallo approached, holding the shovel with which they made mud, and sarcastically asked them what they wanted.

Khalil looked him directly in the eye and told him that they had come to subject him to the same fate as Shekir. Khallo got ready to use his shovel, but Khalil, his brother, and Ahmed Agha battered Khallo with a cudgel, injuring Khallo more severely than Shekir had been. Khalil threatened the other baldırıçıplak Turks with the same fate as Shekir and Khallo. No one dared to say anything to Khalil.

[page 58] During this time, more than thirty armed men took refuge in the mountains. Almost all of these fugitives were deserters from the army. It was September, and the vineyards were not yet harvested. Not only the Armenians but also the Turks were targeted. However, the Turks were armed and could use weaponry, whereas the Armenians were either unarmed or, if they were armed, would not dare use their weapons. These fugitives were not harsh on the Armenians, but they were not soft either.

One day, we met some of these fugitives on the Chenedje Mountain. We were four in total—on their side there were two well-armed men. They asked us if we had any food. We answered that we only had some bread and a small piece of cheese. We gave them all we had. One of my friends had a live chicken and he asked them if they wanted to also take the chicken. They took it without initially agreeing to it and ordered us not to say anything about this encounter to anyone.

The fugitives lived up on the mountains for more than a month, vandalizing the vineyards, and stealing sheep and killing them to survive. They also invaded homes and took whatever they could find. Destroying walls and stealing cattle and chickens had become a natural occurrence. Vandalism was an everyday event. Every morning when we went to the water source to bathe, we were sure to hear a new story of invasion and robbery. Armenians started spending sleepless nights, and life became unbearable again. [page 59] They were once more very nervous about the situation and did not know where to turn. The aghas wanted the criminals arrested and jailed. Their vineyards were also ruined. Khalil Agha’s chickens were stolen and killed, their feathers were scattered on his front doorstep. The aghas did not reveal the extent of their losses. Who was responsible? Both Turks and Armenians surmised that there must be a local mastermind behind all the criminal activity, because the stolen merchandise was not hauled to the mountains but stayed hidden in the village.

Tefik, the son of the town barber, himself also a barber, spoke good Armenian. He secretly confided to an Armenian that the fugitives gathered in Hadji Hafiz Agha’s house at night and that he thought that Hadji Hafiz Agha was the mastermind of this criminal activity. Tefik warned Armenians not to mention his name, otherwise it would be the end of him. Armenians held a meeting during which this secret was revealed without mentioning Tefik’s name. In order to confirm the accuracy of this information, they loaded their mules and, as if they were arriving from another village, every ten minutes each man passed through the mosque door and in front of Hadji’s house with a loaded mule in order to check the identities of the people entering and exiting [page 60] the house. These volunteers worked as detectives at night; they saw everything and passed by in silence. Thus, they were absolutely certain that Hadji was indeed the head of the criminal activities. Other Turks also thought that Hadji Agha was in contact with the thieves. But Armenians wanted to get the aghas to be their friends and supporters by having “the dog catch the wolf,” so they informed the aghas that Hadji Agha was in contact with the thieves, that they slept in his stable, that his house was the center of thieves and that he was their leader. The aghas’ answer was that if the Armenians were sure, they should go to the government headquarters to complain—and they did so.

During those days, a government inspector from Constantinople visited our village and the surrounding villages in order to fairly examine all the crimes and outlaw activities that had occurred during five years. A mandate (buyrultu) had come from Mezire months ago, which read: “If someone’s rights were violated, if there has been corruption, and if you have turned to the government regarding this and have not been answered, or if you have never submitted a complaint, now we are ready to hear you out.”

[page 61] This was very encouraging news and the Armenians believed that Hadji Hafiz would be held accountable for all the illegal activities he perpetrated. But who was Hadji Hafiz? He was approximately fifty years old and had come from the Damascus area. He was educated and a very eloquent speaker (not to say a coaxer). He was capable of convincing a snake to leave its hiding hole. When he spoke Arabic-Farsi (18), common Turks could not understand him. He lived very comfortably, was well dressed, and owned a hunting dog, a hunting bird (doğan) (19), a maid, and a servant. He owned a small piece of land in the region of Umri Sagh that was less than ten cheregs. He lived in the village of Khokh for more than twenty-five years and no one had questioned how this man made his living, and how he could lead such a lavish lifestyle without working.