Arapgir: Songs

Author: Armine Hakobyan, 25/01/2016 (Last modified: 25/01/2016), Translators: Roubina Margossian, Hrant Gadarigian

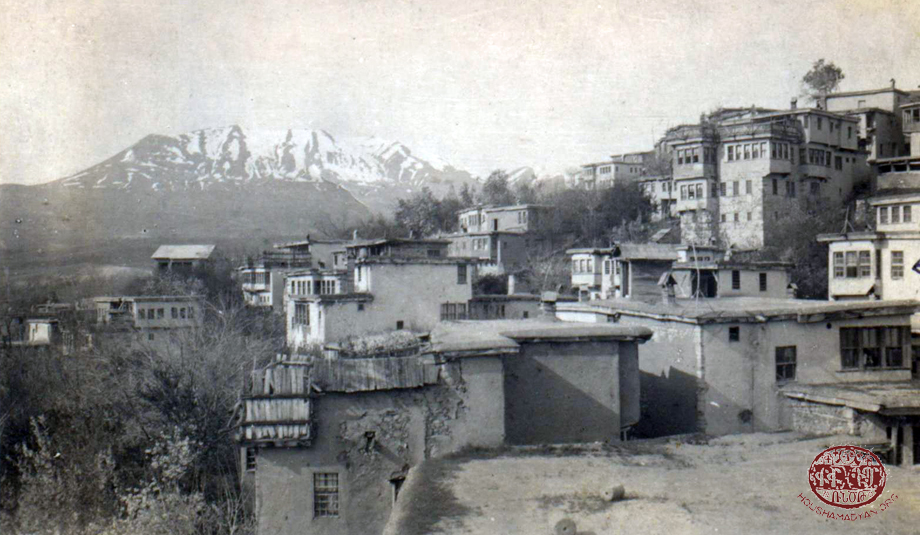

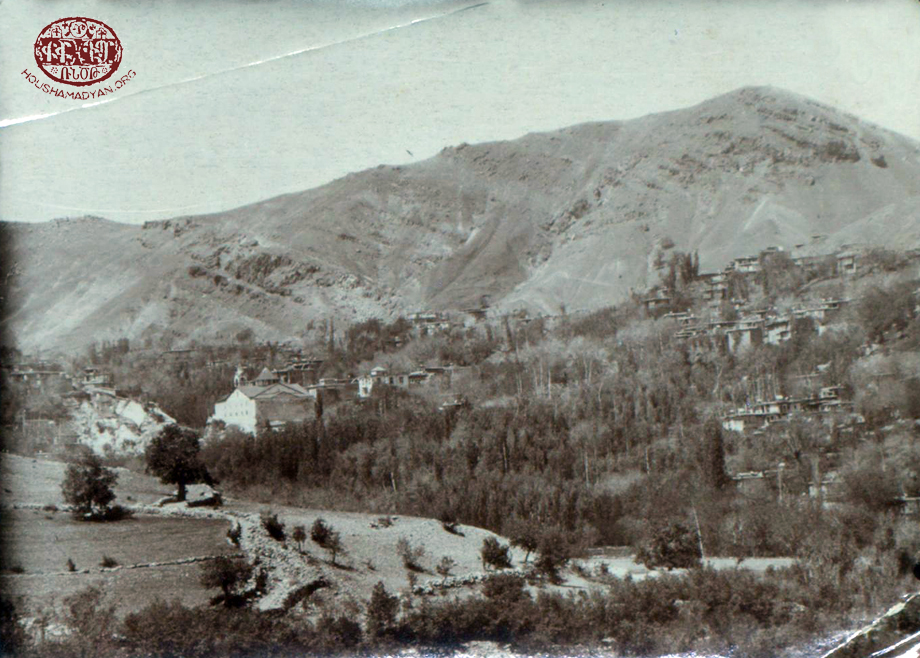

The Arapgir region was rich in song and dance. While the town of Arapgir was known for its trades and commerce, it also had a vibrant cultural life. Armenian residents of the town were an energetic lot who never turned down an opportunity to make merry, to sing and dance.

Holidays and rituals

Folk song and dance were an inseparable part of various rituals. Religious holidays were accompanied by music and, of course, singing and dancing. These holidays included KiudKhach, Asdvadzahaidnoutyunan/Mgrdoutyoun, Amanor, and the pagan-era Deruntarach (locally called Derudas) and Paregentan, that starts prior to Great Lent (Medz Bahk). Traditional instruments (kamancha, saz and tambourine, etc) provided the music. The dance song Tamzara was a favorite for celebrating Paregentan. It was a line dance with the head dancer waving a white handkerchief. Everyone would join in. [1]

Tamzara [2]

Couples would take advantage of the Paregentan holiday to meet, flirt, and sing songs of love.

You’ve gotten up, standing in the doorway,

Decked with silver and gold, [unclear], showing your face. [3]

******************************

Someone pretty standing in the doorway,

Also having fastened a belt on her narrow waist.

She makes gestures with her eyes and eyebrows-come inside,

The image of that pretty one is worth a thousand gold pieces. [4]

******************************

I go up to the balcony, it’s cold-I freeze,

Her loved one comes, I follow,

Let the Lord not take my soul, let me die and be consumed. [5]

(Song recited by Pakhdigian and transcribed in New York, 1935)

There were numerous other unique traditions besides the holidays. One of them was Mama Chttig. It was a ritual during which people sang to God asking for rain after a long drought.

What does mama chttig want?

She wants rain from God,

Give, Dear God, give,

A flood with the rain… [6]

Folksong

Regarding the music and song of Arapgir natives, I must confess that only a few songs have reached us. Only the poetic portions of many songs have survived. Given that folksongs are an oral art form, many examples have naturally been lost. When it comes to preserving the folksongs, history, ethnography and aspects of daily life of the region, the following Arapgir natives have contributed much – Antranig Poladian, Avedis Mesouments and Sarkis Pakhdigian. In Poladian’s History of Armenian Arapgir, original folk and bard songs written down and reworked by Avedis Mesouments appear. Here are a few of them.

Akh, hullei, hullei…[7]

Akh, to have been, to have been,

A potter like my father,

To have been the one to give the string to the potter,

Believe me – for your sweet love

[unclear] I would have painted.

To have been, to have been,

To have been some ivy,

To have fallen in your vegetable patch,

To have reached your window,

To look day and night.

To have been, to have been,

To have been the Ango stream,

With every rush of water

To bring you to my breast

To tightly, tightly hug you.

A beautiful love song. The young man is willing to wait, with longing and patience, so that one day he will win the hand of his beloved.

Mandr - Mandr [8]

Hey mandr, mandr, mandr (small, fine)

Hey mandr, mandr, mandr

You play dzandr, dzandr, dzandr (precious)

You play dzandr, dzandr, dzandr

People danced to this song. As the title says, they danced compactly, in a small space. The subject would spin like a top within a small radius. This is a typical Arapgir dance song. [9]

The folksong ‘A rose also grew in Arapgir’, transcribed by Mesouments, depicts the agony of an unlucky soul.

Arapgerou mech al vart pousav (A rose also grew in Arapgir) [10]

A rose also grew in Arapgir

A stone the height of Horop [unclear]

[unclear] two apples

Saw the holy light [unclear]

The evil devils came from behind,

[unclear] lighted incense and candle

The mountains collapsed [unclear]

The bushed cried, [unclear]

Nazenis (Oy, my dear Nazeni) [11]

- Oy, my dear Nazeni, let’s go to our garden; let’s go to our garden

- The roses have bloomed, the roses have bloomed, and the pears have ripened,

- Let me love your father, your mother, bride and mother-in-law, and sister-in-law,

- And when you come from the bath, let me love your sweet, sweet fragrance.

A happy and energetic dance song. When the words are done, a new melody kicks in imparting a lively rhythm. It is possibly the merit of the Arapgir musicians. [12]

Ouni – Ouni [13]

Pears have ripened in the garden

Cover them; it’s cold

The father-in-law with the [unclear] head

Has seen your kissing

This amusing song has its own history. It is said that one day, in the Almasegan bath, fire, and smoke flew out of the furnace towards the bathers and the women, without wasting time, ran out in terror. Here’s one verse regarding that episode.

The Almasegan bath

The secret of the bosom,

One is looking for a shirt,

Another for the underwear. [14]

Aghchig na nay [15]

Snow has fallen on the mountains na, nay

The field is misty

Dear [unclear] na, nay

The situation is bad

The grapes have also ripened na, nay

Worms are inside

To married girls na, nay

Her name is orphan

******************************

This song is only known in its poetic form:

Mayram has put up a tent

Orman mountains,

She grazes a flock to one side

One side lambs.

And we, fine girl

Have come to you,

With a thousand flirtations

To take you.

Don’t cry fine girl,

Be our bride,

Yakhout (precious stone),

Be a precious emerald to us,

Not sold, not changed

Become our richness,

Be a fertile and radiant faced dear to us.

Girl, we have brought you

A comb made from the tooth of an elephant,

Your gold pleated hair

Is braided preciously,

You are a moonlit face,

Your words sweet,

Whether you want to or not

You will dance fine.

They also take a girl

Weeping and crying,

They also braid the hair

With golden thread

They also cover the head

With a nightingale’s shawl

They also adorn the fingers

With Indian henna

It’s a very endearing, melancholic song associated with wedding rituals. But it’s also a love song and a song of the émigré experience. [16]

Mani [17]

This is a very emotional émigré song. The love song of the unlucky émigré is brilliantly expressed in the lyrics and music.

The magpie also calls out inshallah (god willing) it's a good news.

Mother, mother,

The post comes tomorrow bringing news.

[unclear] the beloved comes, where is your boy,

Mother, mother,

Mother, mother,

From crying, curtains are hung from my eyes.

The caravan comes, what silk fabrics does it carry?

Mother, mother,

There are many seas and mountains between us.

Come home, come home, my boy, come home

Mother, mother,

This world is worthless. We are destined to die.

A nightingale has come and perched on a rose,

Mother, Mother,

Alight is burning in the middle of your two eyebrows

I loved with much love; I didn’t reach my longing,

Mother, Mother,

Send a drop of water to extinguish my fire.

I’ll go to the garden all [unclear] has ripened,

Mother, Mother,

Roses have opened, the rehan has blossomed.

The man has seen the eyes of the dear.

Mother, Mother,

Hand in hand, he/she has serenely come.

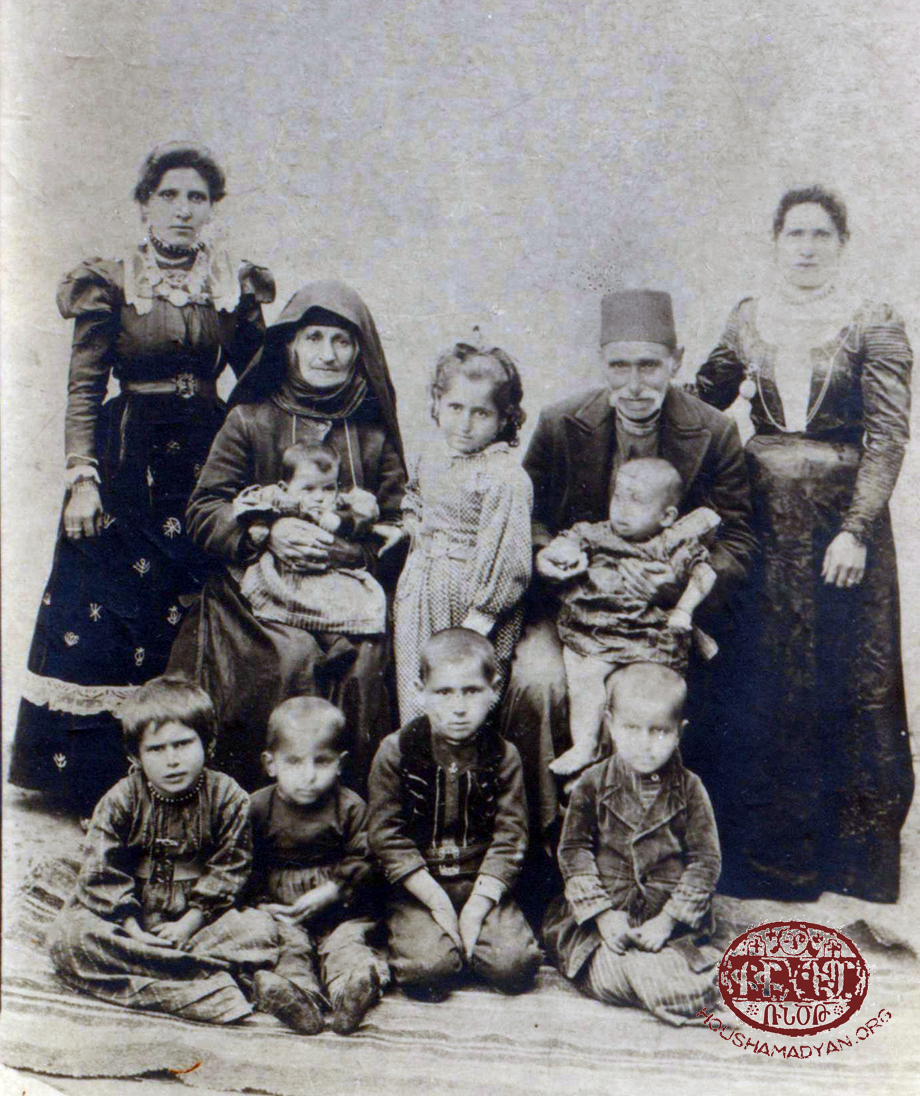

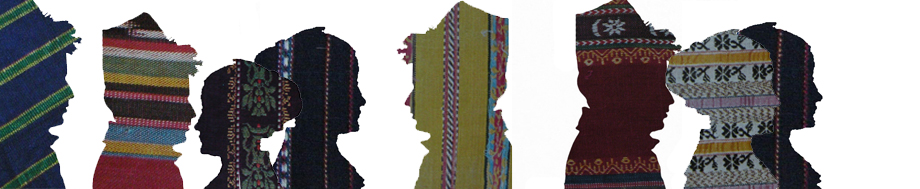

The Arzoumanian family, Ancherti village (present-day Topkapı) in the Arapgir region, 1907. Standing from left to right are: Shnorhig, Varvare (the grandmother, seated), Arousyag (on the grandmother's lap), Arpig (standing between the grandmother and the grandfather), Boghos (the grandfather), Sdepan (sitting on grandfather's lap), Trfanda (standing). Seated on the floor, from left to right are: Martha, Markar, Garabed and Boghos (Sources: National Archives of Armenia, Yerevan, courtesy of Dirk Roodzant)

Mihran Toumajan, a student of Gomidas, also transcribed the folksongs of Arapgir. Toumajan was a master at uncovering and writing down folksongs, a skill he inherited from his teacher. He transcribed the songs directly from Arapgir natives – H. Djavayian, Hovhannes Mamasian, Mrs. Mamasian, and Diran Zorebanian.Toumajan lived in the United States as of 1923. Many Armenians from Arapgir also found refuge there after 1915. The songs transcribed from Arapgir native singers were the songs and dance songs displaying the traditional mores and mannerisms of western Armenians. They are diverse in content, their melodic structure is interesting, and the emotional range extensive. Given their genres and poetic themes, we can say that the songs are varied. They are wedding songs, songs for rituals, and songs of love, especially the manis (oriental folk song), dance songs, laments and songs of exile.

We know that in ancient times weddings were celebrated with great pomp and circumstance. People then were traditionalists. In their view, an Armenian girl must be modest, tidy, obedient, a good housekeeper, and respectful of her seniors. In terms of appearance she must have a round face, red and white, a narrow nose, open forehead, black hair long and thick, a smallmouth, a long neck, an ample bosom, thick hands and tiny feet. [18]

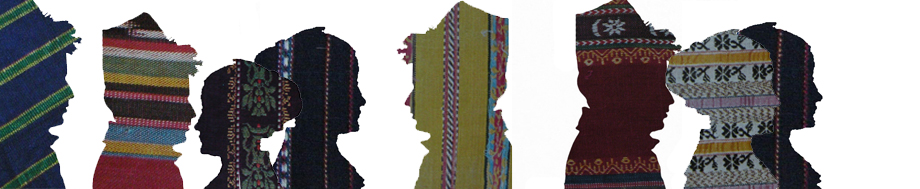

Armenian family from Arapgir; Identity unknown (Source: George Djerdjian photo collection)

Weddings in Arapgir were ceremonial in nature, and were always accompanied by music, song and dance. Before the wedding ceremony, the boy’s family would visit the prospective bride’s home (aghchigdes), followed by khos gab (verbal promise) and nshantrek (engagement). [19] Wedding preparations started eight days before the event. The girl would be painted with henna. On Saturday, she would be taken to the bath house. [20] At midday, they would come to braid her hair. All would participate. The godmother would start to braid the girl’s hair with golden thread and sing. [21]

Aghjign al goudanin [22]

We are also taking a girl, anam,

In health and glory.

They are also braiding her hair, anam,

With golden threads.

They are covering her head, anam,

With a nightingale’s shawl.

(This song, recited by Hovhannes Mamasian, was transcribed in Boston, 1936)

When braiding hair they also sang:

A pretty one goes, anam, to the threshing floor,

Her shape is thin, chinar (plane tree), anam,

Girl nanana.

(This song, recited by Pakhdigian, was transcribed in New York, 1935) [23]

An example of a wedding song is “They play a saz at our door”. It was danced in groups and individually; in turns. In gatherings of women, the bride would dance to this song surrounded by unmarried girls. During mixed gatherings (men and women), the bride and groom would be invited to dance. The dance was noteworthy for the modesty and embarrassment it portrayed of an Armenian girl. It can be regarded as one of the best examples of an Armenian feminine dance. [24]

Mer touruh gzarnen saz (They play a saz at our door) [25]

They play a saz at our door,

They play a saz at our door.

Let the sisters-in-law braid the hair,

Let the sisters-in-law bear her coyness

Our door resembles a yard,

The fringes resemble a crown.

The bastard came and went,

Know that he resembles a beg (agha)

(Recited by Hovhannes Mamasian, this song was transcribed in Boston, 1936)

Presented below are examples of songs and dance tunes whose melodies as well as sometiems lyrics represent instances of city life. These songs are accessible to all segments of society; Armenians, Turks, the rich and the poor.

An Aghchigan (For the girl)

(first version)

Galoshes for the girl,

Boots for her mother,

A pair of open-faced shoes for the father

He could do without a monkey too [26].

(second version)

Put a pair of galoshes on that girl,

Boots on her mother,

A pair of open faced shoes for father,

He could do without a monkey too [27]

(Recited by Mrs. Mamasian and transcribed in Boston, 1936)

An babigan (For the father)

(third version)

Chnkoush shoes for the father,

I won’t care any more / I won’t attend anything else [28].

(Recited by Diran Chorebanian Mamasian and transcribed in Boston, 1936)

Tsvikin koveruh (At the sides of the roof) [29]

The “Tsvikin koveruh” song, with its vocal modulations, is traditional:

Are you gently pushing a donkey at the sides of the roof, my boy?

Your shadow shows [unclear]

(Recited by H. Djavian, this song was transcribed in Boston, 1936)

A few manis also transcribed by M. Toumadjan:

Ouy, mandr, moundr

Ouy, fine, small, fine,

The head [unclear] comb.

(Recited by Diran Chorebanian Mamasian and transcribed in Boston, 1936) [30]

Paghchan ee var chour gerta (Water flows down from the garden)

Water flows down from the garden,

Let’s go and see where it flows,

The water gives a false reason,

It goes to see its betrothed.

(Recited by Mamasian and transcribed in New York, 1936) [31]

Shehrin paghchan tour ounee (Shehir’s garden has a door)

Shehir’s garden has a door,

It also has fine water inside,

The plums haven’t taken,

They have a fine skin

Have, have, have, have,

They have a fine skin.

(Recited by Hobvhannes Mamasian and transcribed in Boston, 1936) [32]

Tours Em Kotser (I’ve Shut My Door)

I’ve shut my door,

Gone to the bathhouse,

Gone, gone,

Gone to the bathhouse.

(Recited by Diran Chorebanian and transcribed in Boston, 1936) [33]

Baghcha Ounim, Bar Chounim (Got a Garden, Don’t Have Fruit)

Got a garden, don’t have fruit,

Got quinces, don’t have pomegranates,

I’ve ended up in a foreign land;

Got no way out.

(Recited by Hobvhannes Mamasian and transcribed in Boston, 1936) [34]

The theme of emigration has always been present in the songs of emigrants from Arapgir. Due to economic hardships and a harsh local taxation system, emigration from Arapgir was widespread and this theme naturally found it’s way into their songs.

Across fron Agn is a rocky mountain,

To yearn is to indure, to count it to die.

(Recited by Hobvhannes Mamasian and transcribed in Boston, 1936) [35]

******************************

The magpie calls, God willing it is a good omen,

Get up mother, get up and say a prayer,

The other’s son arrives, where is yours?

(Recited by Pakhdigian and transcribed in New York, 1935) [36]

******************************

It is snowing on the mountains, the fields are misty,

Jinxed is the one who separates the bird from its mother.

(Recited by Pakhdigian and transcribed in New York, 1935) [37]

The Bosphorus (the sea of Istanbul) is wavy,

The breeze of love blows sweetly,

If God grants me the fortune, I’d go to her,

Get my wish and fall into the sea.

(Recited by Pakhdigian and transcribed in New York, 1935) [38]

**********************************

Lower mountains, lower yourselves, let me pass over you,

My beloved migrated, let me reach after him/her.

The stranger’s beloved has reached [unclear],

The beloved’s story is passed in black.

(Recited by Pakhdigian and transcribed in New York, 1935) [39]

The verse transcribed by Toumajan “Your Handkerchief is Dirty” is a tragic story [40]. An interesting fact, the songs recited in Arapgir, Agn and Chmshgadzak are often very similar, they practically sang the same songs with slight differences and each attributed these songs to be their own. These places were not so far from one another and it is natural that there is often confusion about the origins of some song though they are often contributed to Agn [41]. The following is a vivid example taken from the Alakeozlou folk song treasury.

Agn version:

Your cloths are dirty,

Send them for me to wash.

I’ll put them on my wet eyes,

Lay down and sleep.

(Gomidas) [42]

Arapgir version:

Your handkerchief is dirty, send it for me to wash.

I’ll put it on my wet eyes, lay down and sleep.

(M. Toumadjan) [43]

Your Handkerchief is Dirty

We come across Alakeozlou in only Western Armenian music folklore. It is the product of collective popular musical tradition and in essence, is deeply traditional and ancient.

What are known as Alakeozlou songs in Armenian folklore, represent a certain mix of poetry and music. In content, they tell stories of migration and feelings of deep longing.

******************************

In Poladian’s opinion, some of the songs transcribed by Gomidas that are popular to this day, are a part of the Arapgir musical tradition [44].

Aman Telo

Shoghor djan

Aravodoun pari louys (Good morning at daybreak)

Sareri Vrov gnats (Left over the mountains)

Troubadour Culture

Troubadour culture had a special place in Arapgir. Troubarour songs are a considerable part of the humble collection of songs that have reached us. Love was one of the central themes that inspired the troubadours and is one of the main subjects of their songs, though we also come across songs, which discuss social and other matters. The troubadours thought of themselves as common folk and their songs often addressed different social circles with moral lessons, advice on worldly matters; teaching them to differentiate between good and evil. Troubadours also had a mission to praise aesthetics, admiring that which was beautiful, good and true. Philosophical reflections, judgments and conclusions on life were also a part of their creations which often included humor, sarcasm etc.

In Arapgir, troubadours mainly sang in Turkish, a mixture of Turkish and Armenian, in Kurdish etc. The names of some Troubadours have reached us like Khridar, Tourapdar, Sel Sefil, Der Margos … who unfortunately are not mentioned in Armenian publications about Troubadours. It needs to be mentioned that very few troubadour songs have survived in writing. There are songs that reached us orally through time and it is only natural that different people recited them differently, subjecting them to change over time.

Troubadour Khridar

Chronologically, Khridar (or Khrigdar) is the oldest mentioned troubadour from Arapgir. He is assumed to have been born between the years 1720-1730. Khridar is a pseudonym. His real name was Hovhannes Yerzngatsian. Khridar likely means someone who wears old shoes, because in that area, khrig or khrrig meant old shoe or footgear. Troubadours being wanderers, there is the opinion that shoes must have been the most warned item of their clothing. This pseudonym can also be explained in reference to the Persian word Khiriydar meaning skilled, experience, accomplished. It is possible that the “i” and the “y” have been compressed resulting in the word Khridar [45].

It is told that one evening Khridar invites a Turkish friend to his house. Amid the festivities, the Turkish guest kisses Khridar’s drunken wife. Khridar angrily picks up his saz and this is what he sings [46].

I saw, she took my mind, the brave among the princes,

Are you the soul of my soul, you beauty,

Have mercy.

When love has mercy the soul delights,

How I would burn, that’s my soul’s pain,

The heart weeps, those sweet lips of yours,

Your honey sweet lips, your amber teeth,

The beauty spot on your face, it’s a fault to kiss,

Your body slender, royal purple attire.

Your bosom a rose, a ripe orchard,

The huntsmen await, they expect from there,

The smell is of quince and pomegranate.

Let me commit my crime among the pomegranate trees,

Let me be your servant, my lover with henna on her hands,

A letter to my lover does you harm.

Come my love, give me your word

Don’t, don’t deny your love,

Tell me the remedy, I’ll stake my head,

I’ll stake my head, make the pain vanish,

She’ll get drunk on wine I’m afraid,

You gave a kiss to the stranger, I saw it then and there,

How can it be in the house,

Your servant Khridar,

Laments and moans,

Gone are pride and shame,

My sight blunted,

I’ll beg for forgiveness. [47]

After finishing this song, Khridar slams his saz to the ground and leaves his house and his wife that same evening [48]. With a broken heart, disappointed, and crushed, with a heavy heart the troubadour sings “İsyanlıdan kerem, kerem” (Isyanlı or as called Yessenatsioutoun in Armenian, was a religious school of redemption that Khridar was a follower of).

İsyanlıdan kerem, kerem [49]

Grace, grace to the Yessenatsi,

I will not get attached to the world,

Other than you trustworthy,

Not a confidant is left.

Don’t give your secret to your friend,

He too has a friend,

There will come a day when,

He too will confide (in his friend).

But in this world, there is one, trustworthy, dedicated being to whom he can rely his pain and sadness [50]. That is Khridar’s mother, he addresses her through his song “ My mother, I have a plea”. The following is the first stanza, which is half in Turkish, half Armenian [51].

My mother, I have a plea

To my silent imploration,

Give mercy and affection

In tears my eyes are going blind [52]

Below we present a couple of songs attributed to Khridar:

You are like the sun [53]

You are like the sun, there is none like you,

Dressed in slick tailored silk

That exquisite silk drives me crazy,

I draw sorrow from my heart

I have sorrow for you, you have no idea,

You have black eyes driving me crazy,

What if you listened to me carefully,

Let me kiss you on your cheek

Just a little kiss, you’ll have honored me,

I’ll sacrifice my soul to you my love,

I’m troubled, can not take your teasing,

What if one day you came to me

What if you come and cool my little heart,

At my dyeing hour, praise my name,

Bury Khurigdar with your own hand,

Fall on the ground (above me).

Has been a while since I saw you [54]

Has been a while since I saw you,

Where have you gone lovely?

Happily you went and stayed

Left me stranded here lonely.

How would I know if you there,

Did not make another love you?

Now, [unclear] you truly made

My fires burn more highly.

Don’t do these things to me,

Heaven will deal with you,

Only in death will I be,

Truly free of you.

I never expected of you,

Such behavior honestly,

Your games and laughter,

Where have they gone, honestly?

You too know this, it’s not apt

The way you hurt me like this,

I’m Khridar, I figured it out,

You’ll regret it honestly.

You have dressed up… [55]

You have dressed up aghvor, aghvor (pretty pretty)

Your cypress height, has reached mine,

Let’s go live a pretty life,

A thousand decades with thousand days.

I lost my head aghvor, aghvor,

When I saw your beauty,

Khrigdar wants aghvor,

A sweet kiss from you.

In the beginning the Lord created

The song “In the beginning the Lord created” (Ibtidaa sdeghdzets Dere) [56] is noteworthy, where Khridar refers to a Biblical theme.

In the beginning the Lord created Adam and Eve,

Warned them not to eat,

Eve did not follow God’s commandment,

Suffered for six centuries.

She suffered and rounded six thousand years,

Again they took a page from the devil’s book,

The light shone through, Adam and Eve that year,

No rust was left in their hearts.

The Lord saved them from the rust,

Rejoiced Adam, Eve our mother,

Upon the word, father Abraham,

Fasted for forty days.

Fasting and keeping lent is good for a person,

To enter God’s divan barefaced,

St. Garabed grant a wish to Khridar,

Pour, give, let me drink from your hand.

Troubadour Tourapdar/Tyurabdar

The other troubadour is Tourapdar. He was born around the 1750s in Arapgir. His name means earthly, earthen. In Arabic, Tourab mean soil, dust and Dar means house, residence. His real name was Arakel Mamigonents, which is later distorted and becomes Mangigian. Tourapdar was the father of a large family; he had seven children [57]. Many interesting stories about him have reached us, like the following: It is said that when Khridar hears of Tourapdar’s name and fame, he invites Tourapdar to compete with him. They climb up the courtyard of the Oulou mosque (djami), inside the walls of the fortress, take a seat under the plane tree and compete with one another for seven days and seven nights. The competition ends with Tourapdar’s victory [58]. Khridar dubs him a troubadour and gives him his saz [59].

The following is a segment of that historical duel (the original is in Turkish):

Who is this comer

Khridar

Nimble hearing, strong champion,

The beauty with masterful hands is the comer,

With heavy dues and sweet words,

A hundred thousand horsemen is this comer.

Tyurapdar

There is a mark on my tongue; my pain is twice one,

Day and night, mourning and lament is this comer,

Burns with love, not every water will extinguish,

A heart full of fire is the comer.

Khridar

His hands are skillful, sweet and precious,

Ear with piercing, with fine teeth,

Eye stamped in jewels, bows for eyebrows,

Stone falcon gazed love is the comer.

Tyurapdar

Beg God for a cure,

Find your own luck, don’t look to the cheat,

I fell into this crater of love and fire,

A slave to pain is the comer.

Khridar

Cypress trunk with a phantom, green emerald,

Royal train, a purple shawl,

Face with twin beauty spots, honeysweet lips,

He himself sweet, the language of love is the comer.

Tyurapdar

Does not take body form from soil, or sleep from his eyes,

Does the one who knows books never lie?

The books don’t tell of shame,

Unlearned of foul answers is the comer.

Khridar

Don’t be mad dear, my liver is gurgled,

I have earthly words and a saz in my hand,

With a word or two paying respect,

Khridar from Arapgir is the comer.

Tyurapdar

Not an orchard or rose garden,

Laying in the ground, chest in upheaval,

Has love crazed sorrow, his soul suspended,

Child son Tyurapdar is the comer. [60]

As we see, both are excellent masters who create and perform their own work. Khridar’s songs are more earthly in context while Tourapdar was more of a moralist, spiritualist Troubadour. Fairness, respect and honor were Tourapdar’s main precept. The following is his message to men.

Spiritual, beautiful, rich, wise,

You worked day and night;

You built a house so kind,

Respect my words,

Relay them to one another

Love your parents.

We are stuck at the end of the world [61]

“We are stuck at the end of the world” (Ahrı zemana kalmışız…). This song is too is a call for justice where Tourapdar makes moral judgments about the world.

We are stuck at the end of the world, oh princes, gentlemen,

Mercy has perished from the world, there is no justice,

I’m full of pain and grief, my eyes cry blood,

Not a single law abiding officer is left.

Princes do not implement the words of the Lord,

Fraudulently they abuse all of humanity,

Without a bribe they will not move their pen to benefit justice,

There is not an honest, civil policeman left.

The corrupt policeman lives as a slave to his passion,

Wants there to always be food and drinks and entertainment,

Has no mercy for the poor and does not look left and right,

There is no clean craft, a fair earning for the tradesmen any more.

The farmer sows nothing grows, the son does not obey his father,

The wife does not listen to her husband’s word; this is why times are worst.

Tourapdar’s words, daughters who learned from their mother,

At seven years old they prey on men, this is why times are worst.

Tourapdar was much loved by both Armenians and the Turks. It is said that when he played, people would forget about the church and the mosque. It is known that he has been exiled to Ourfa but it is not clear how long he stayed there and when he returned [62].

Once, at the marketplace, the Muslims were making fun of Tourapdar. Tourapdar would often make rough and daring remarks about the Muslim religion and for this reason he was beaten and was almost went to trial a couple of times. Urban legend has it that things got to the point that he had to go to Istanbul and stand before the Sheikh Al-Islam and the Sultan. Other than being brave and daring Tourapdar was also resourceful, had a sharp mind, was an adept poet, was a master of wordplay techniques and thanks to this, he was almost always able to talk and perform himself out of similar trouble [63].

One day Tourapdar was going around with his saz hanging on his shoulder, a judge insults him with a smirk by calling the saz a devil. In retaliation, Tourapdar takes down his beloved instrument and starts to sing a song announcing beforehand [64] “I’m not speaking now, I’m only translating…”

The song is called “Tut Ağaçtandır Teknesi” [65] (This box is mulberry wood)

This box is mulberry wood

This box is mulberry wood,

The keyboard is of intestine,

A pastime for the brave and the migrant

Where is the devil in this?

The bar is a pear tree,

The strings come from France,

You God’s stupid servant,

Where is the devil in this?

When I pray, does not tell me not to,

When I wash, does not object,

Is more honest than a judge,

Where is the devil in this?

The name is troubadour Tyurapdar,

Tragedy has reached the Maker’s heavens,

You big headed ass of a judge,

Where is the devil in this?

The stories about Tourapdar are many. All of them are interesting and unique and all testify to the troubadour’s strange personality and singular character. It is told that, foreseeing his own death; the troubadour organizes his own funeral. People reprimand him for it but Tourapdar stubbornly walks to the graveyard where a religious ceremony takes place and before it is the turn of the burial he says his last words [66].

Hear my words [67]

Hear my words, princes and sirs,

In this earth my heart wore out and went,

Bearing sorrow and pain and crying blood,

My body and essence wore out and went.

Word has reached this earthly being from the city /cemetery/,

The soul is not salvaged from the bitterness of life,

From man’s enmity, fate’s conquest,

Alas, my tender life wore out and went.

Luck is a watermill, people grains,

It crushes all, leaves out not one,

When people, those searching, ask “where is he?”,

Tell them, Tyurapdar was here but then he went.

It is not known if Tourapdar was actually buried that day or not [68].

Rose water, beloved, your hair

Tourapdar also has love songs so typical of troubadours. “Rose water, beloved, your hair” [69] where he praises his beloved is a confession of love. Only the Armenian translation of this song is known to us.

Sprinkle you hair with rose water,

My love, coyly, coyly,

Divide into seventy parts,

Braid it coyly, coyly,

When has my beloved woken from her sleep?

Don’t blink your sea eyes,

Come to the garden, pick

Red roses, coyly, coyly.

The blush on your face took my wits away,

Dried the sleep from my eyes,

Light up the house of my heart,

My darling, coyly, coyly.

The sea is Tyurapdar’s priest,

Your love became my wind,

Wonders around, falls from place to place,

Winnow, coyly, coyly.

Troubadour Shevkia

There is very little information about Troubadour Shevkia. It is said that he went to Persia to make some money. In a café one day, a rival troubadour addressing Shevkia sings;

Go around Iran if you want to be an emigrant, go around Turan,

Instead of being wealthy in exile,

Go around as a beggar in a wealthy world.

Shocked by the sudden discovery of his identity, Troubadour Shevkia picks up his saz and immediately returns to his homeland [70].

Bloyents Surma

In the 1850-s a troubadour named Bloyents Surma also lived and created in Arapgir. It is known that Bloyents Surma was not educated but was well acquainted with church hymns and prayers and has translated some of them into a common speaking language to make them accessible for a wider audience. According to S. Pakhdigian, Surma was a red haired woman, a bread baker by profession, a critique and someone who lived an active social life [71]. Bloyents Surma describes her inner world as such;

(in Turkish)

Veremli Bloların Sırma dertlidir,

Derdimi arz edersem ferman olur.

(translation)

Tuberculosis stricken Surma’s Blo is suffering,

If I spoke about my pain, it would be a firman.

A piece that has reached us from Surma is a critique of the subsidy handed out to people following the 1895-96 anti Armenian massacres.

Regarding the same 1895 massacres, Bloyents Surma also has a verse addressed to the Kurds:

(in Turkish)

Kürtler de malımızı talan ettiler,

Yıkdiler şen geynimiz, veran ellediler,

Yeyin de keyf edin üzüm basdığır,

Üzlerinize çıksın eşek arusu,

Biz kurtulduk, size ola darısı [72].

(translation)

The Kurds have stolen our properties,

They’ve destroyed our land, devastated it.

Enjoy them while they last, grapes suppress hunger,

May wasps cover you all

We were saved, we wish the same to you.

In his interpretation of this song, Avedis Mesouments writes, “It was a prediction or a prophecy or it was a curse that came true (…) the Kurds too had the same fate, they too drank from the cup of massacre, slaughter and displacement to the last drop”.

Other Troubadours

The following and segments by troubadour Sel-Sefil and troubadour Faouzi.

Powerless, Incurable [73] (Troubadour Sel-Sefil)

(the original in Turkish)

Powerless, incurable, wallowing in pain,

Isolated, gone are we from the world,

We drank down the full cup like it was poison,

Wicked words repulse us from life.

My tongue can not utter, it’s unsayable, unknowable,

My pain, anguish, my heart is deep, it does not show,

Full of pus it suffers, does not wipe out,

Need a surgeon to cut it open on one side.

A wounded heart is incurable,

I searched for a balsam, that I never found,

There is not a person who could save this Sel-Sefil,

But may be there still is cure for my wound.

Brothers, Listen Up … (Troubadour Faouzi) [74]

Brothers, listen up, I’ll tell you one thing,

Going to the church and crying is needed,

Night and day the good and the bad are by a thousand,

Paying tax, giving alms is needed.

At every hour ask the Mother Mother of God,

Luminous beams she bent into an arch,

She brought to light her only son,

Spilled red blood, crying is needed.

God created man in his image,

He put us out of heaven, we had no idea

Came and effaced hell, we have no idea,

Turning back from a life of sin is needed.

This world will pass, the judgment day will come,

Hey~ Favzi, how are you going to give an answer?

Peter and Paul are laying in Ferengistan (France)

We are going, the rick is needed (or crying is needed? )

(Recited by Father Moushegh Seropian)

Priest Der Margos A. Arapgirtsi was also a troubadour from this region, about whom we have almost no information. It is only known that such a priest existed [75]. Kor Kevo, Keoroghlou, Hadji Kerem Arenderian, Gornag and others were also troubadours who lived in the area during the 19th and the 20th century. [76]

Even though he does not belong to the ranks of troubadours, the name Mgrdich Der- Bedrosian is worth mentioning. He was knows in Arapgir as a musician and a teacher. He was born around the 1870-s in the village Dzag. Presumably, he received his primary education at the local St. Nshan school and then in Arapgir, later he completed his education at the St. Hagop seminary in Jerusalem where he was ordained a deacon. He has founded a hundred member, male and female choir performing four part harmonies. He had a beautiful velvety voice [77]. Mgrdich Der- Bedrosian is the author of the words to the song “Hovouyerk”. As a sign of respect to the Vartabed, A. Mesouments wrote the music to his words in the 1930-s [78].

It needs to be said that a large part of the humble collection of songs that have reached us were transcribed and arranged by Avedis Mesouments. It is also thanks to his dedicated work that today the music of Arapgir is available to the future generations.

[1] Antranik L. Poladian, History Of Armenians of Arapkir [in Armenian], New York, Baykar press, published by the Arapgir Association of America, 1969, page 196.

[2] Ibid, page 278.

[3] Mihran Toumajan, The Song and Word of the Fatherland [in Armenian], vol 2, Yerevan, ASSR AS (Academy of Sciences) press, 1983, page 362.

[4] Ibid, page 362.

[5] Ibid, page 374.

[6] Poladian, page 202.

[7] Ibid, page 264.

[8] Ibid, page 265.

[9] Ibid, page 237.

[10] Ibid, page 266-267.

[11] Ibid, page 268-271.

[12] Ibid, page 237.

[13] Ibid, page 272-274.

[14] Ibid, page 237-238.

[15] Ibid, page 275-277.

[16] Ibid, page 238.

[17] Ibid, page 279-282.

[18] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Arapgir And Its Surrounding Villages, Historic-Ethnographic Brief View [in Armenian], Beirut, Vahakn press, 1934, page 81.

[19] Ibid, page 79-83.

[20] Ibid, page 90-91.

[21] Ibid, page 96.

[22] Mihran Toumajan, page 131.

[23] Ibid, page 362.

[24] Ibid, page 242.

[25] Ibid, page 139.

[26] Ibid, page 172-173.

[27] Ibid, page 172- 173.

[28] Ibid, page 172-173.

[29] Ibid, page 173-174.

[30] Ibid, page 174.

[31] Ibid, page 176.

[32] Ibid, page 178.

[33] Ibid, page 180.

[34] Ibid, page 171.

[35] Ibid, page 360.

[36] Ibid, page 363.

[37] Ibid, page 367.

[38] Ibid, page 374-375.

[39] Ibid, page 375.

[40] Ibid, page 161.

[41] Poladian, page 236.

[42] R. Ataian, Gomidas, Collected works [in Armenian], vol 9, “Kidoutyoun” press, Yerevan 1999, page 103.

[43] Mihran Toumajan, page 360.

[44] Poladian, page 239-240.

[45] Ibid, page 211.

[46] Ibid, page 213.

[47] Ibid, page 214.

[48] Ibid, page 214-215.

[49] Ibid, page 251-253.

[50] Ibid, page 215.

[51] Ibid, page 249.

[52] Ibid, page 249-250.

[53] Ibid, page 242.

[54] Ibid, page 248.

[55] Ibid, page 246.

[56] Ibid, page 244.

[57] Ibid, page 216.

[58] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Troubadours of Arapgir [in Armenian], published by the Compatriot Association of Arapgir and Surrounding Areas, Beirut, 1943, page 11.

[59] Poladian, page 220.

[60] Ibid, page 220- 222.

[61] Ibid, page 260-261.

[62] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Troubadours of Arapgir, page 19.

[63] Poladian, page 216-217.

[64] Ibid, page 217.

[65] Ibid, page 255-256.

[66] Ibid, page 218.

[67] Ibid, page 257-259.

[68] Ibid, page 259.

[69] Ibid, page 253.

[70] Ibid, page 224.

[71] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Troubadours of Arapgir, page 28.

[72] Ibid, page 28-29; Poladian, page 224.

[73] Poladian, page 223 and 262.

[74] Ibid, page 223.

[75] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Troubadours of Arapgir, page 27.

[76] Poladian, page 225.

[77] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Troubadours of Arapgir, page 36.

[78] Poladian, page 291-292.