Yaghdjian/Yiagjian collection - Athens

Translator: Simon Beugekian, 14/10/22 (Last modified 14/10/22)

The memory objects and materials presented on this page were collected and catalogued during Houshamadyan’s workshops in Athens on April 1st and 2nd, 2022.

This page was prepared collaboratively with the “Armenika” periodical of Athens and the Athens chapter of the Hamazkayin Cultural Association. Houshamadyan’s workshops were made possible thanks to the support of EVZ Foundation, Germany.

This family history, which begins in the region of Kharpert and continues in Greece, was provided to us by Siranoush Yaghdjian/Yiagjian and Haritini Andridzaki. Later, Saro Dedeyan, Siranoush’s son, also contributed to our efforts to collect and decipher the photographs in the collection.

The Yaghdjian name was very prominent in the village of Keserig/Kesrig (present-day Kızılay) and its environs, in the area of Kharpert/Harput. The prominence of the family owed much to Hadji Ovan (Hovhannes) Yaghdjian, who was a merchant and who enjoyed close relations with many of the political elite in Constantinople. Ovan Yaghdjian had two children, Krikor and Mariam. The latter married Krikor Tashdjian and had six sons with him: Hagop (1860-1930), Sarkis (1878-1934), Hovhannes/John (1866-1953), Dikran (1883-1949), Bedros/Peter (1877-1940), and Soghomon. Notably, Krikor’s sons all adopted their mother’s surname, and were thus all called Yaghdjian. Soghomon was the youngest of the six brothers, although his precise year of birth is unknown. He married Yeghisapet Kalunian, a native of the city of Kharpert.

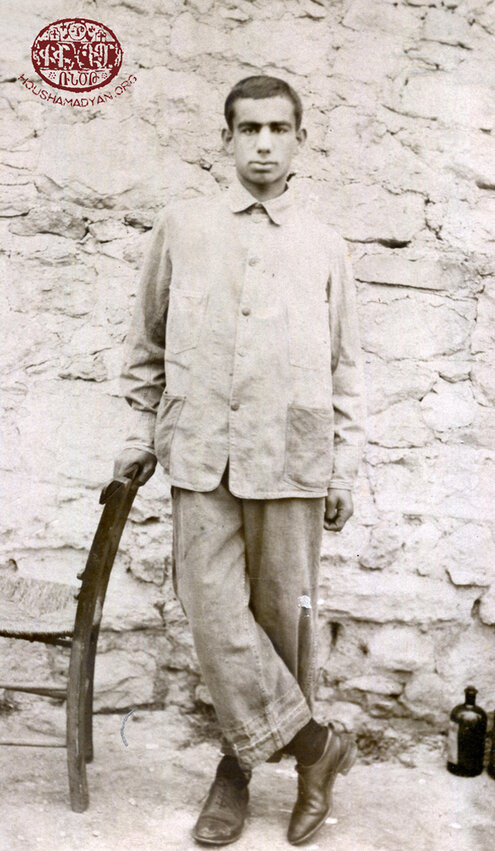

According to one of the family’s descendants, Marc Yagjian (who lives in the United States), based on information that he received from his father and other family members, Soghomon visited the United States in the early 1890s, initially finding work in Worcester (Massachusetts). While there, he learned the art and craft of photography, which he continued to practice after his return to Kharpert. According to Marc, the many photographs of Keserig are Soghomon’s works. According to Haritini and Siranoush, Soghomon was even invited into the homes of local Turks, as a photographer, to photograph Turkish women and girls.

According to Vahé Haig’s book Kharpertn yev anor Vosgeghen Tashdu [Kharpert and its Golden Valley] (New York, 1959, page 883), during the 1895 anti-Armenian pogroms in the area, Soghomon, alongside many other Armenians from Keserig, was arrested by the Ottoman authorities. The men were taken to Sivas, where the court deemed them to be revolutionaries and condemned them to death en masse. By then, Hadji Ovan Yaghdjian had passed away, but many of his friends still held high-ranking positions in Constantinople. Thanks to their intervention, the court’s verdict was rescinded. Soghomon and his friends returned to Keserig on December 26, 1897.

Soghomon’s wife, Yeghisapet, was the daughter of Mariam and Baghdasar Kalunian. Baghdasar was a photographer by trade. Yeghisapet attended the Euphrates College in Kharpert, from which she graduated. Thereafter, for three years before her marriage to Soghomon, she worked as an English teacher in various villages throughout the Kharpert valley. The Kalunian family were members of the Armenian Evangelical community.

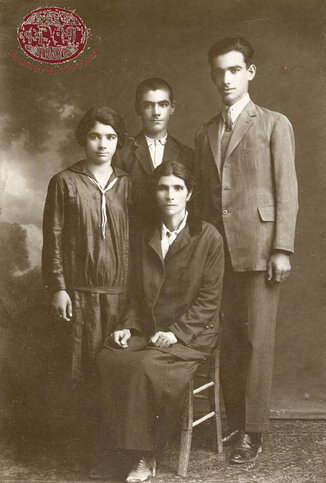

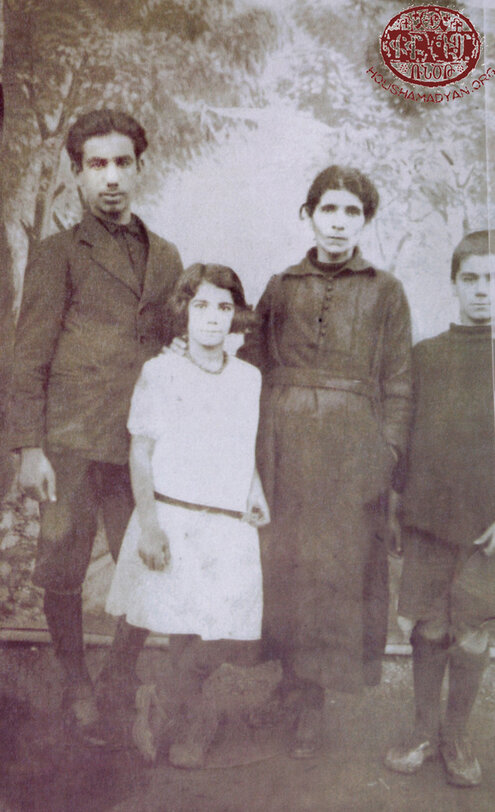

Soghomon and Yeghisapet had four children: Siranoush, Mihran, Papken, and Zabel (born in 1913). Mihran was Siranoush Yiagjian-Dedeyan’s father, and Zabel was Haritini Andridzaki’s mother. Presumably, after the couple’s wedding, the entire family moved into the Yaghdjian residence in Keserig. After migrating to Greece, family members often reminisced about their stately house and their life there. The exterior of the house was designed like a fort, and Soghomon would often travel around Keserig and its environs on horseback. When remembering the past, Zabel would also often recall that she and her siblings played with a local boy, named Fikri Sakup, the son of a high-ranking Turkish official. His name will appear again in this family history.

When the First World War broke out, Soghomon enlisted in the Ottoman Army. While in service, he struck up a friendship with the son of a Turkish pasha from the area of Kharpert (name unknown) who served alongside him. This Turkish officer secretly informed Soghomon that massacres of Armenians were being planned; and advised him to leave the country with his family immediately. Soghomon, finding an excuse to go on leave, made his way back home. With him, he carried a letter written by his friend the officer and addressed to the latter’s father. In the letter, the officer asked the pasha to protect Soghomon’s family from the violence. In fact, the pasha took the family under his wing. Nevertheless, Soghomon himself was imprisoned, probably when the arrests of the prominent Armenians of Kharpert began. He was initially held in the local jail, where his family could visit him. But later, he was taken away in an unknown direction, and was most probably murdered along the way. Whatever the details of what befell him, Soghomon’s family never heard from him again.

The Armenian Genocide had begun. A childless woman, a neighbor of the Yaghdjians, offered to take in Siranoush, who was about ten years old at the time. The family agreed to the proposal. Yeghisapet’s other children, Mihran, Papken, and Zabel, hid in the pasha’s house. But the police often searched the area, and so the pasha moved them to a nearby village, where the police were less active. The Yaghdjians began working around the village: Mihran herded cattle, Papken watched turkeys, and both brothers worked as harvesters during harvest season.

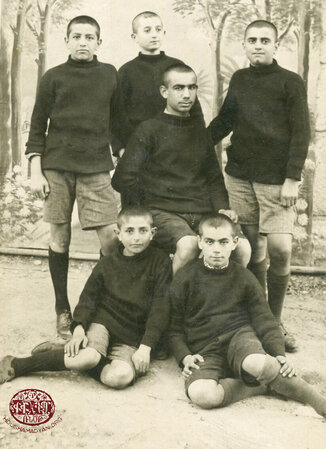

After the end of the First World War, Siranoush was reunited with her family. Around this time, the American missionaries who had left due to the war returned to Kharpert and resumed their work with even greater vigor. Yeghisapet and her children, too, returned to their family home, presumably in Keserig. The house was occupied by Turks, but the family was able to reclaim ownership of it. According to family history, it was this home that hosted the local American Near East Relief (NER) orphanage, which sheltered 100 to 200 orphans. The existence of an orphanage in Keserig is confirmed by Manoug Djizmedjian’s book, Kharpert yev ir Zavagneru [Kharpert and its Children] (Fresno, California, 1955, page 487). Yeghisapet’s children also attended this orphanage-school, while she was employed as a teacher in the same institution.

The Yaghdjians remained in Keserig until 1922. In that year, the NER, succumbing to pressure from the Turkish government, was forced to close its orphanages across the country, including the orphanage in Keserig. All wards of these institutions were transported to Syria. The girls and boys traveled separately, with the girls traveling on the backs of oxen or mules and the boys traveling on foot. The two groups were accompanied by Kurds as guides and guards.

Mihran, Papken, and Zabel also found themselves among the orphans who arrived in Syria. Meanwhile, Yeghisapet remained in Keserig, hoping to convince Siranoush to leave Kharpert and accompany the rest of the family. Sometime between 1919 and 1922 (we are not certain of the exact date), Siranoush had married Fikri Sakup, who, as we have seen, was also from Keserig, was the son of a local high-ranking official, and was a childhood friend of the Yaghdjian children. But Siranoush was determined to stay with her husband in Kharpert. Yeghisapet even attempted to abduct her own daughter, but failed. Eventually, Yeghisapet left for Constantinople without Siranoush.

Mihran, Papken, and Zabel boarded a ship in Beirut that took them to Constantinople. Yeghisapet soon joined them in that city, which, at the time, was under the occupation of the Allied forces (particularly British forces). After arriving in the city, the female members of the family were sent to a large palace that had been converted into an NER orphanage. Yeghisapet applied for a job at this orphanage-school. No teaching positions were available, so she was initially hired as a washer. But the institution’s leadership soon noticed Yeghisapet’s intellectual abilities and offered her employment as a teacher.

The Yaghdjian family did not stay in Constantinople for very long. Armenian orphanages were closing and relocating to Greece. The Yaghdjian family joined this exodus, too. At first, they settled in Loutraki. There, the NER had rented a large hotel, which had been converted into an orphanage. Yeghisapet’s children attended this school-orphanage. By this time, the family had received visas to immigrate to the United States, but the visas were stolen, and the family did not apply for replacements. They remained in Loutraki for about two years, then proceeded to Oropos, north of Athens, also home to an American NER orphanage. Once again, Yeghisapet was employed by this institution.

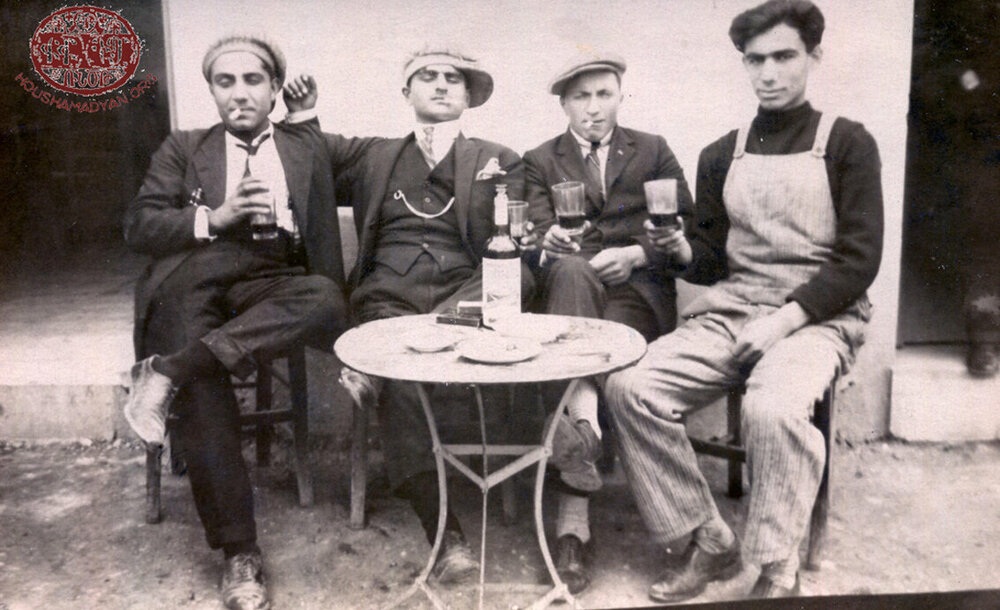

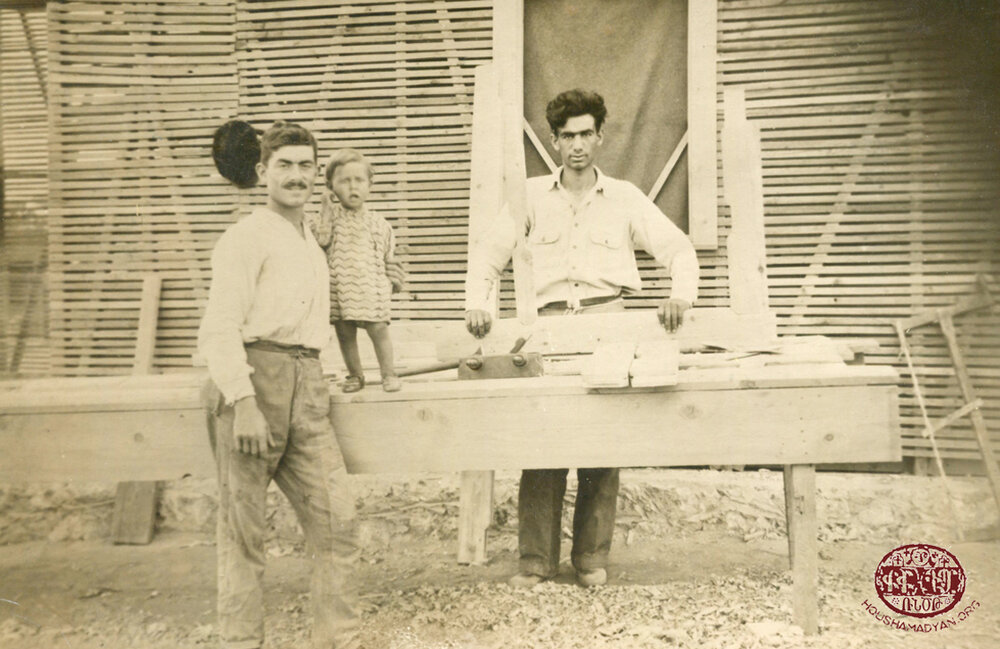

The family then moved to the Fix/Dourgoúti neighborhood of Athens, where they lived until 1928. In that year, a catastrophic earthquake struck the city of Corinth, reducing much of it to rubble. Mihran and Papken, who had learned the craft of carpentry at the orphanage, saw this as a good opportunity to move the entire family to Corinth, where there was great demand for master builders to help rebuild the city. The first to make the journey to Corinth was Mihran. He was soon joined by the rest of the family. Zabel and Yeghisapet founded an Armenian school in Corinth. After some time, Mihran and Papken founded their own furniture workshop, which continued operating for decades. Papken lived in this city until his death. Both Papken and Mihran were members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF).

In Corinth, Zabel married Nikos, who was a Greek machinist from the Greek island of Crete. Their home was always filled with music and song. Zabel played the mandolin, while Nikos played the guitar. Mihran and Papken initially opposed their sister’s marriage to Nikos. At the time, they argued, “We have already lost Siranoush [who had stayed behind in Turkey after her marriage], and now Zabel will marry a Greek and abandon us…” But later, Nikos became a beloved member of the family, accepted by all.

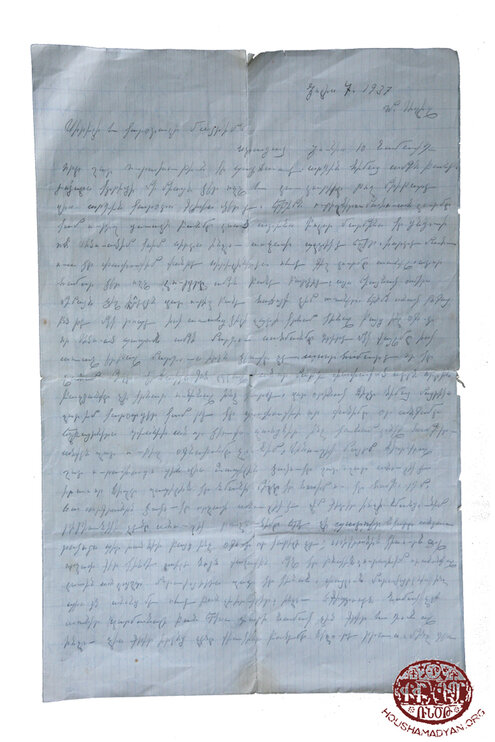

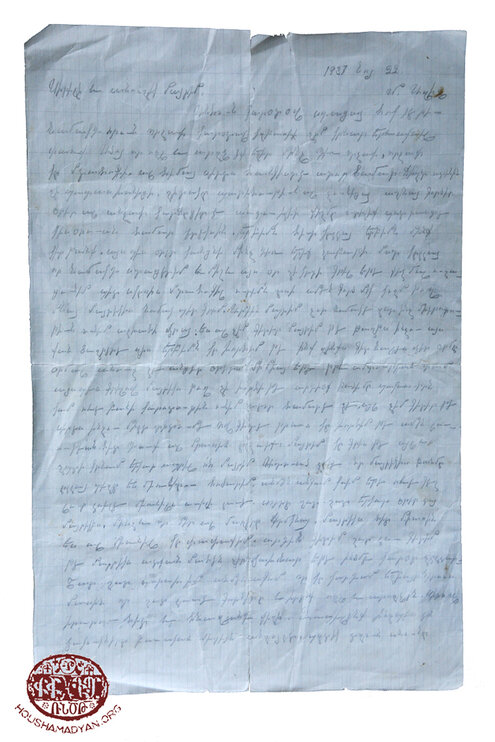

As for Siranoush, she lived in Elazığ (Mamuret ul-Aziz), where her husband, Fikri, was a government official. The larger family believed that the couple had a happy life together. In those years, Siranoush and her mother began corresponding, exchanging letters and photographs. Two of the letters received from Siranoush, as well as two photographs, have been preserved by the descendants of the Yaghdjian family. One of the letters was written on July 7, 1937, in Mamuret ul-Aziz. The letter is written in Armenian, and addressed to Yeghisapet, whom Siranoush calls her “Dear and much-missed mother.” Siranoush writes in clear and eloquent language, interspersed here-and-there with examples of the Kharpert dialect. The nostalgia that Siranoush felt towards her family is conspicuous in her letters. She was kept apprised of family events, wedding, births, etc. She received family photographs from her mother and commented on each. We also know that Siranoush corresponded with other members of the family, including her aunt.

Though Siranoush and Fikri lived in Elazığ, the letters make it clear that they spent their summers in Keserig, most probably in the home that had once belonged to the larger Yaghdjian family. Presumably, Fikri and Siranoush had become the owners of this estate. But it seems that for Siranoush, in the absence of her family, the visits to Keserig were not especially enjoyable. She wrote to her mother, “… But this year, [summer season] was cooler than last. Again, we go to our home in Keserig every Sunday. The home’s fine, but it has a different feeling now … I wouldn’t want to move to Keserig. Our home [in Elazig] is more comfortable, and Fikri’s work is there. There would be difficulties with his midday meals. So, once a week is enough.”

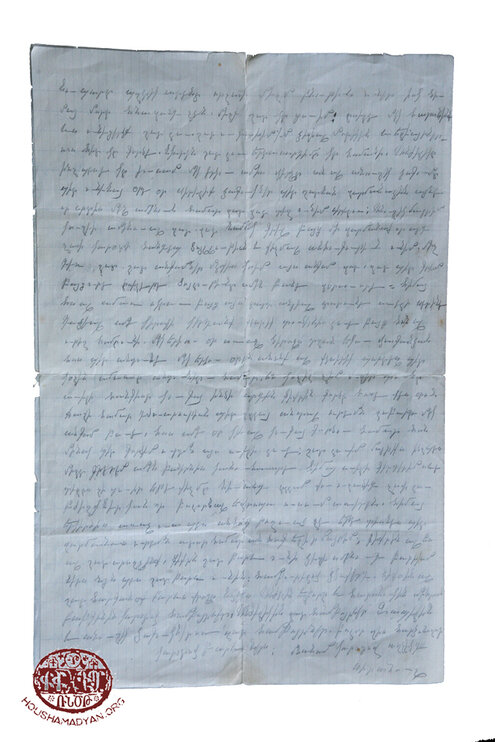

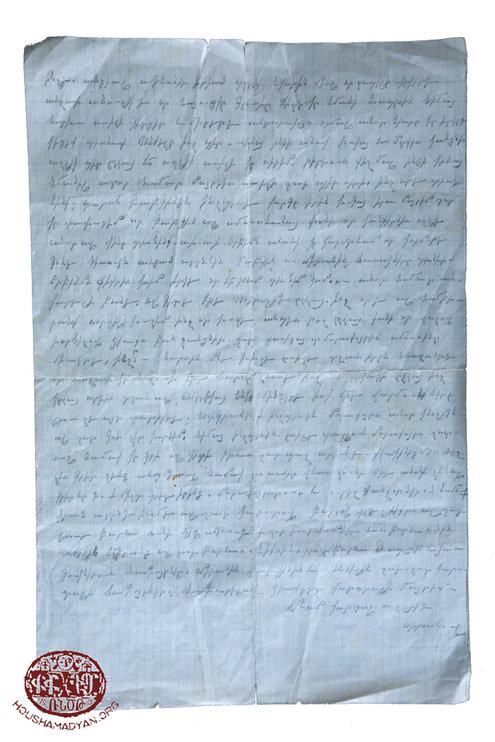

The prevailing theme in the second letter, written on November 22, 1937, is once again nostalgia and the sense of separation from family. In it, Siranoush addresses Yeghisapet as “My dear and beautiful mother.” She writes: “Oh, sometimes I miss you all so much that I just wish I could see Mihran and Papken’s silhouettes in the distance, that would be enough.” But was it not possible for her to travel to Greece to see her family? Fikri was a government official, so presumably, the family had the financial means to afford such a trip. Siranoush writes, “Sometimes, I ask Fikri to send me to see you, but he won’t hear of it.” It is unclear why Fikri would not assent to this. Was he, perhaps, worried that Siranoush wouldn’t return if he let her go? We do not know the answer, and we never will, as Siranoush died a short time after writing these letters.

Siranoush and Fikri often went hunting together. While pregnant with her first child, Siranoush went on another hunting expedition with her husband. It is said that when she fired her hunting rifle, the butt struck her belly. She immediately began bleeding, and a short time later, both she and her unborn child died.

Siranoush’s niece (Zabel’s daughter), Haritini, visited Elazığ in the 1980s. Her aim was to find a trace of Siranoush, to learn more about her life there, and to find her gravesite. But after preliminary inquiries, she realized that people had great reservations about answering her questions, or simply did not wish to speak to her. She returned to Greece empty-handed, having discovered nothing new.

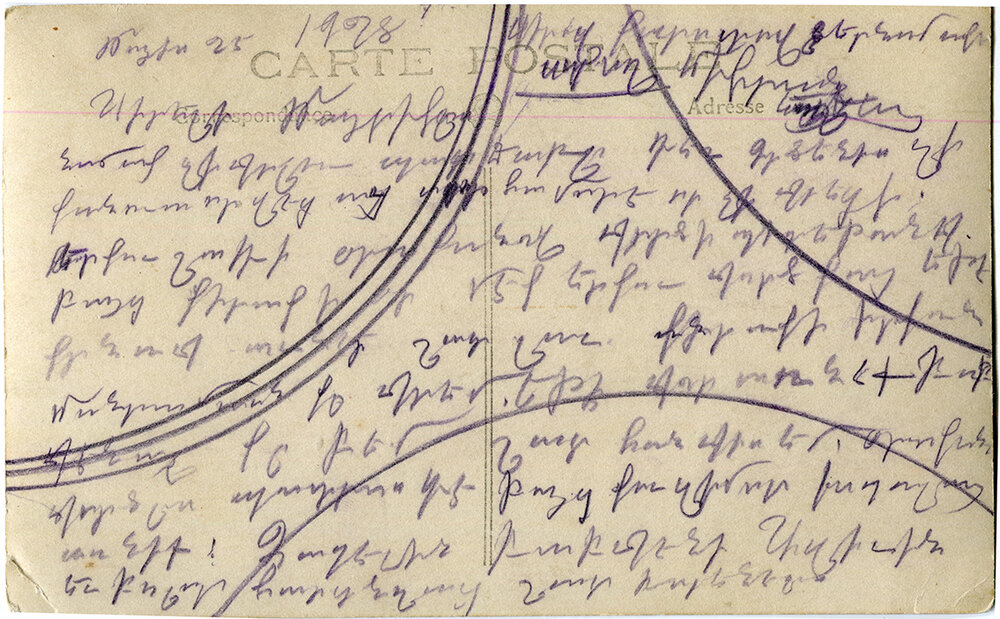

1.1; 1.2) A letter from Siranoush Yaghdjian, dated July 7, 1937, and sent from Mamuret ul-Aziz. It was addressed to her mother, Yeghisapet.

2.1; 2.2) A letter from Siranoush Yaghdjian, dated November 22, 1937, and sent from Mamuret ul-Aziz. It was addressed to her mother, Yeghisapet.

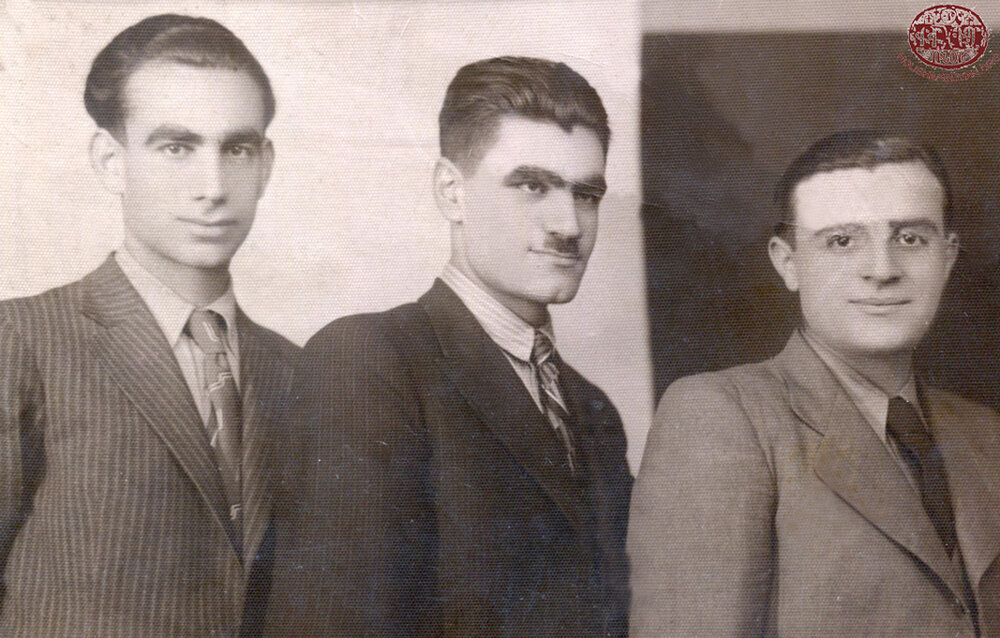

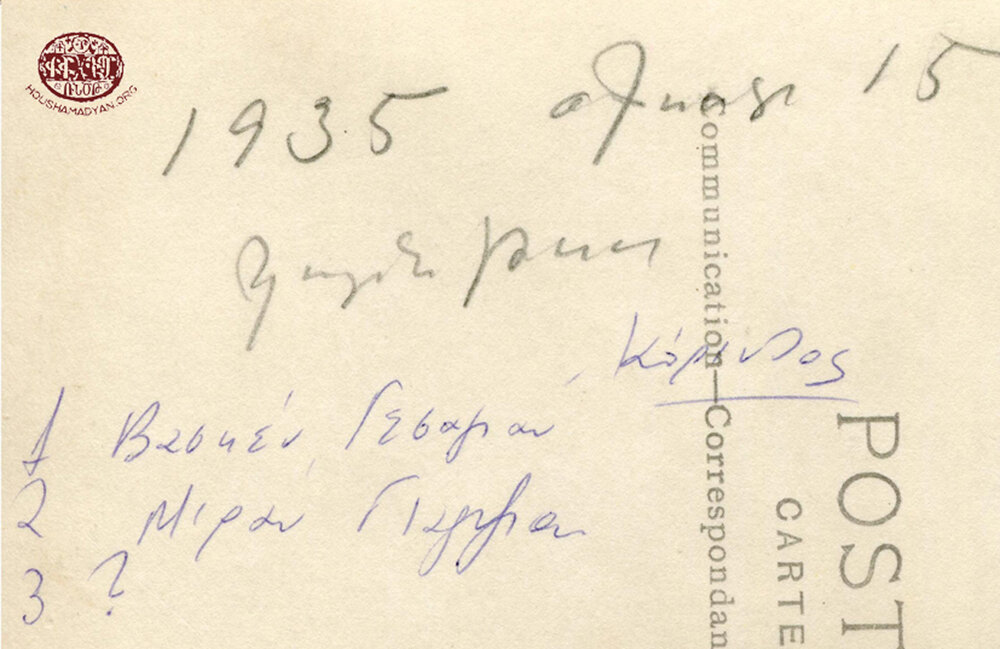

August 15, 1925. Corinth. Left to right: an unidentified individual, Mihran Yaghdjian, and Vazken Yesayan. Vazken Yesayan was born in the Kharpert/Harput area. He was a poet, and a close friend of the Yaghdjian family. He was Siranoush Yaghdjian’s baptismal godfather.

Zabel’s husband, Nikos, owned a car repair shop in Corinth. Between 1941 and 1944, when Greece was occupied by Nazi forces, the workshop was requisitioned by the Germans and used for their war effort. They would bring their tanks and other vehicles to be repaired there. As the Germans began retreating from Greece, Nikos was able to regain ownership of his workshop. But German tanks had been left behind. The retreating Germans, seeing these tanks, accused Nikos of stealing them, arrested him, and took him away to be shot. But Papken intervened with the Germans, explained the situation to them, and saved his brother-in-law’s life.

During the years of German occupation, when hunger and the lack of basic foodstuffs was a widespread problem across Greece, Papken and Mihran converted their furniture workshop in Corinth into a flour mill and oil press. Women from the nearby villages would bring the wheat or olives they had harvested from their fields, and the Yaghdjian brothers would produce flour and oil for them. In this way, the brothers’ factory/workshop contributed to easing the suffering of a hunger-stricken country and community.

Among the employees of the factory/workshop was one Mr. George, who owned a van. The flour and oil produced by the Yaghdjians’ mill/press was transported using this van, which would make trips to the Dourgoúti neighborhood of Athens and distribute aid to the local hunger-stricken Armenians. But the road from Corinth to Athens was dangerous. Locals were so desperate that they would attack the van with the intention of stealing the food. As a precaution, Mihran would always ride in the back of the van, to ward off any such attacks.

Siranoush (Mihran Yaghdjian’s daughter) recalls that during her university days, she had a classmate who was originally from Corinth. One day, this classmate’s father came to pick up his daughter from the university. She introduced Siranoush to him. “When he heard my surname, he immediately asked me if I was Mihran’s daughter or Papken’s. I told him that I was Mihran’s daughter. The man said that my father had saved them from dying of hunger.”

In the 1950s, the Yaghdjian family received an official letter from the Greek government, informing them that they had been granted Greek citizenship in recognition for their services to the country during the Second World War. At that time, most Armenians living in Greece had not yet been granted citizenship. The family received this news just as the Sophia Hagopian Armenian School of Athens was founded. By Greek law, the principal or headmaster of the school had to be a Greek citizen and had to have a university degree. Angel Yaghdjian, Mihran Yaghdjian's wife, was a suitable candidate who met all requirements. And so, she became the first principal of the newly founded Sophia Hagopian Armenian School.

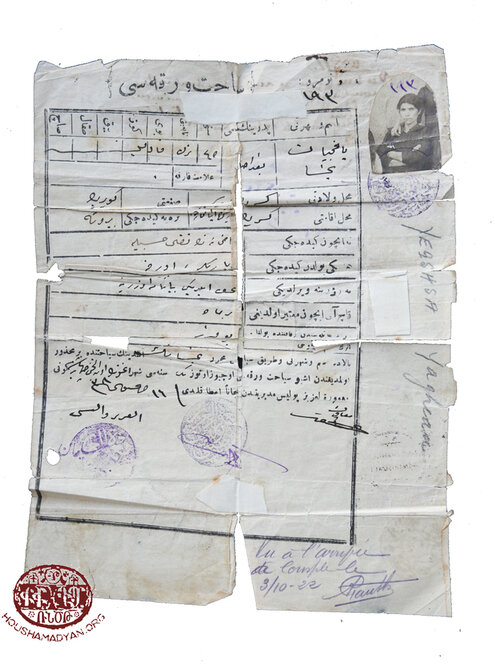

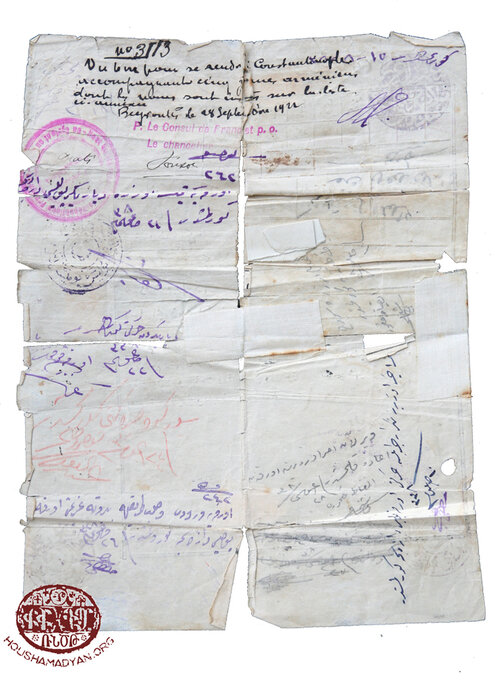

Yeghisapet Yaghdjian’s Ottoman passport, with which she traveled to Istanbul, and from there to Greece. It is dated 1922. The back of the passport bears the stamp of the French Mandate authorities of Lebanon, with a note stating that she was accompanied by five Armenian youth. This information contradicts the family’s oral history, which maintains that Yeghisapet traveled from Kharpert/Harput to Istanbul alone, without ever having traveled through Beirut, and that her children joined her in Istanbul.