Ashdjian Family Collection - Istanbul

Author: An-su Aksoy, 31/10/2022 (Last modified: 31/10/2022)

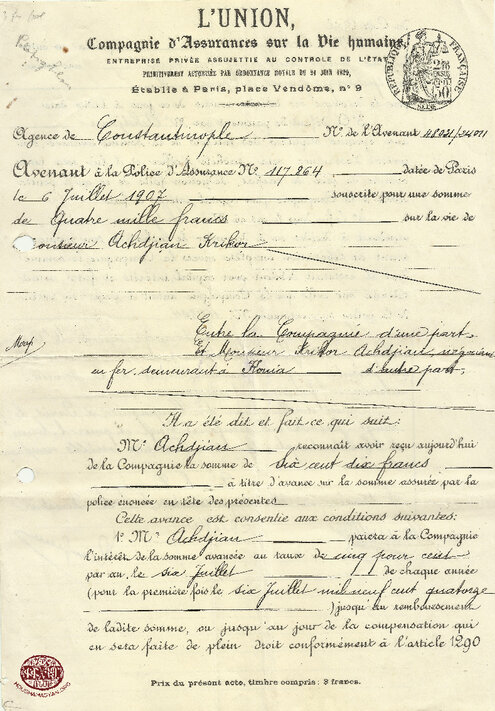

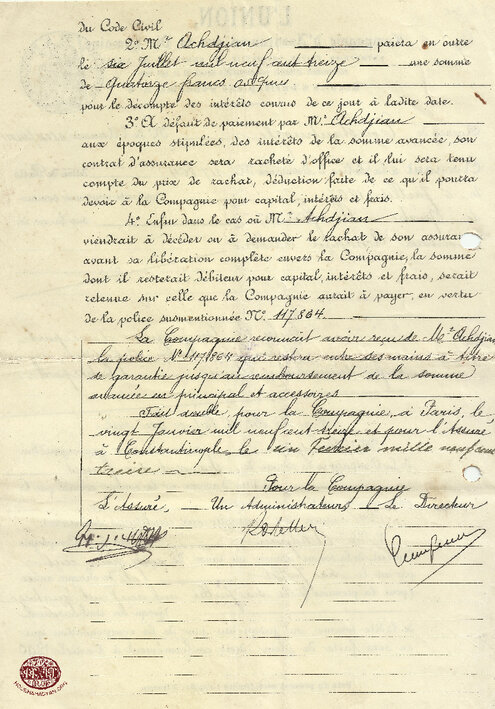

Kirkor (Krikor) Ashdjian (1865-1927) was the son of Hagop Ashdjian. Krikor’s wife was Anna Avakian (1864-1951), the daughter of Andon and Talita Avakian. Anna was born in Konya. Although Krikor lived in Konya, we are not sure if Krikor’s family was originally from Konya or if they settled there from Istanbul where he had strong connections. Not much more is known about the Ashdjian ancestors.

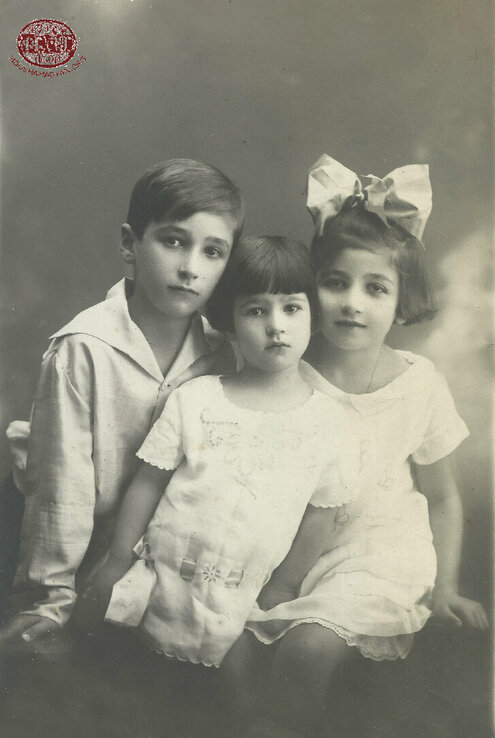

Kirkor and Anna have three children; they are Lousaper, born circa 1880, Maryam, born in 1883, and lastly, Mamas Krikor, born in 1894.

Kirkor owned two shops in Konya, one selling construction materials and the other kitchen utensils. Within the family, he was known for having an official position, one which granted him responsibility over the non-Muslim communities of the city. Family lore tells us that he was able to save many lives due to this position. During the years of 1915 or so, Kirkor was able to get the names of those who were to be deported in advance, and by forewarning them, was able to help them escape.

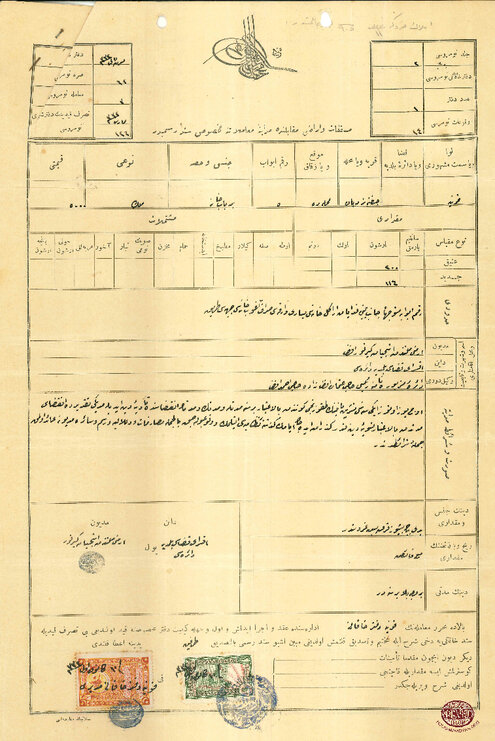

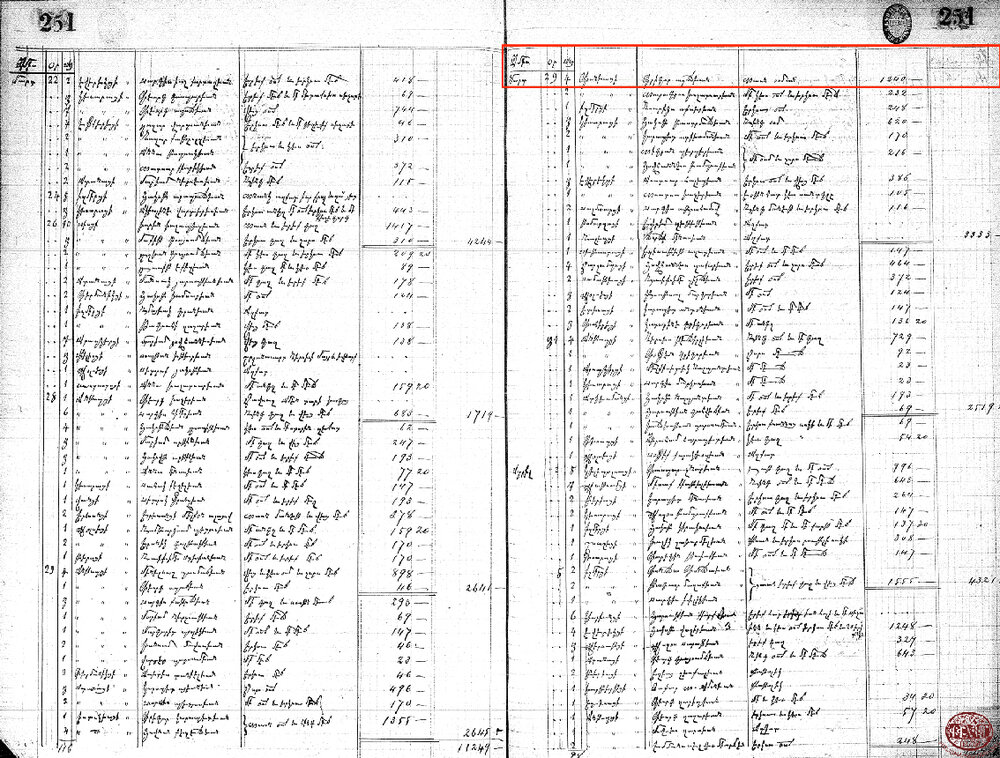

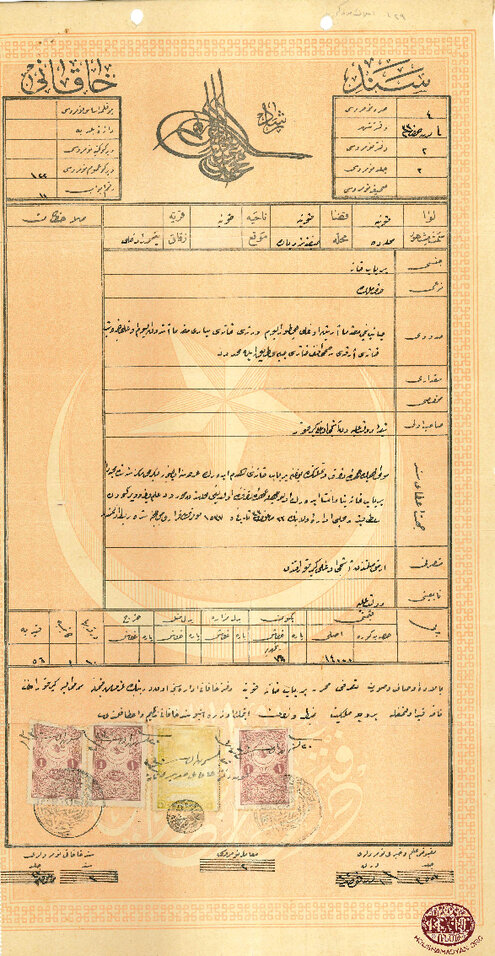

We also know that Kirkor was a member of the “Hürriyet ve İtilaf Partisi.” He was elected to the municipality’s council in the elections that took place on February 1919. The family speculates that he may have gotten into some form of trouble, because his house was confiscated even though he neither perished nor escaped for it had fallen under the status of “Emvali metruke” (or property abandonment). According to an article about Arab refugees and their settlement in Konya, as an example among others, the article cites Kirkor Ashjian’s house being given to a certain Necibe Hanim. In addition, knowing that his son Mamas would request of his children to never get involved in politics also adds to the family’s speculation.

In March 1905, Kirkor and Anna, along with their son Mamas, traveled to Jerusalem. We have a few photos of this journey where we see that they traveled by boat. They brought back with them objects such a jewelry box as a souvenir of their travel.

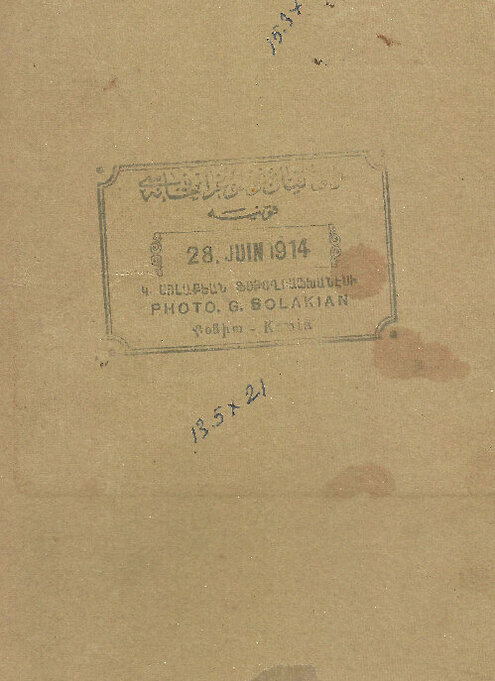

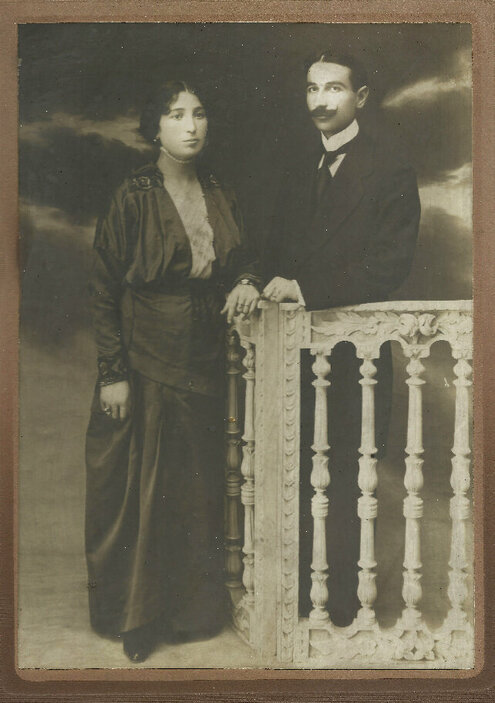

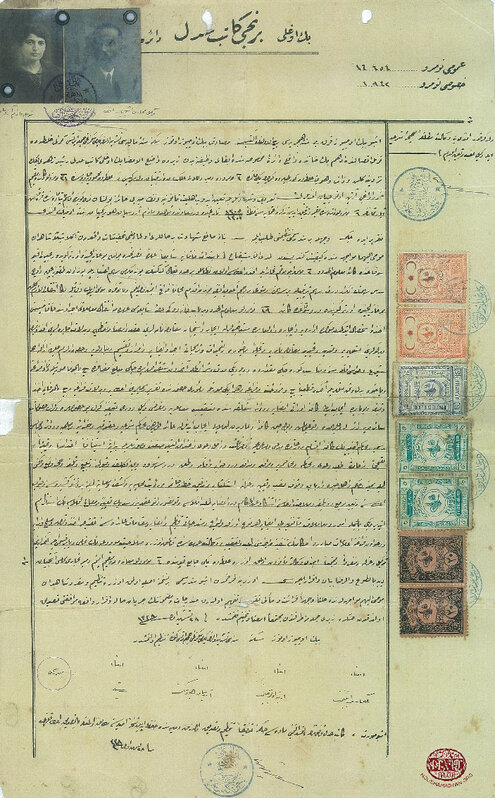

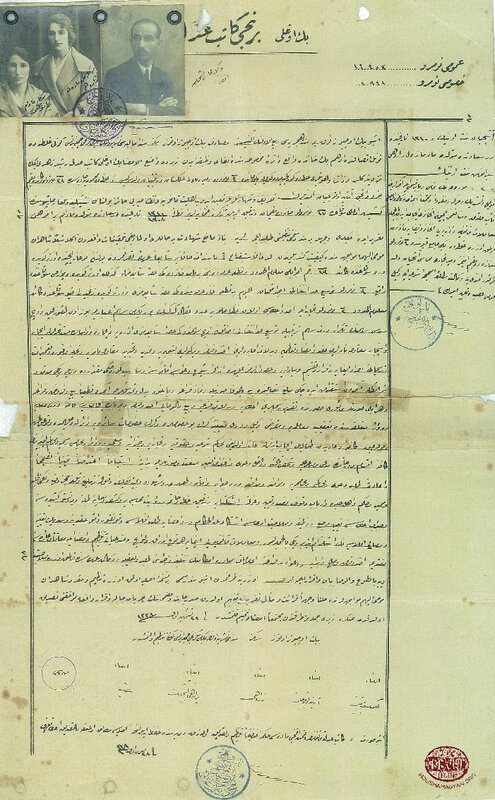

Whether he was originally from Konya or Istanbul, Kirkor Ashdjian always had strong bonds with Istanbul. His accountant was in Istanbul. While his daughters married locals from Konya, when it was time for his son Mamas, to marry, he wanted him to marry a girl from Istanbul. His initial idea was to seek a girl from an orphanage, but his accountant mentioned a good family from Ortaköy, where the children’s mother had died at a young age and the father died in 1911. Thus, the marriage of Mamas Ashdjian with Hripsime Yeranouhi Berberian took place in 1914. Yeranouhi is the daughter of Verjin from Galata, and Ohannes Berberian from Ortaköy. She is the third of four siblings, the younger sister of Haig Berberian, who later escaped from Istanbul, settled in Paris and became a scholar of Armenian history and culture.

After the marriage, Mamas wanted to take his wife to Konya to introduce her to his family. Yeranouhi complied, but with the condition that her sister Zarouhi accompany her. While in Konya, World War I and the genocide started, making it impossible for them to return to Istanbul for several years.

When the war broke out, the family was at the summer house. Considering the situation dangerous, they decided to bury the relatively small but valuable items they owned, such as jewelry, in the chicken coop. They believed they would be able to go back and retrieve them after the war. They were never able to get back.

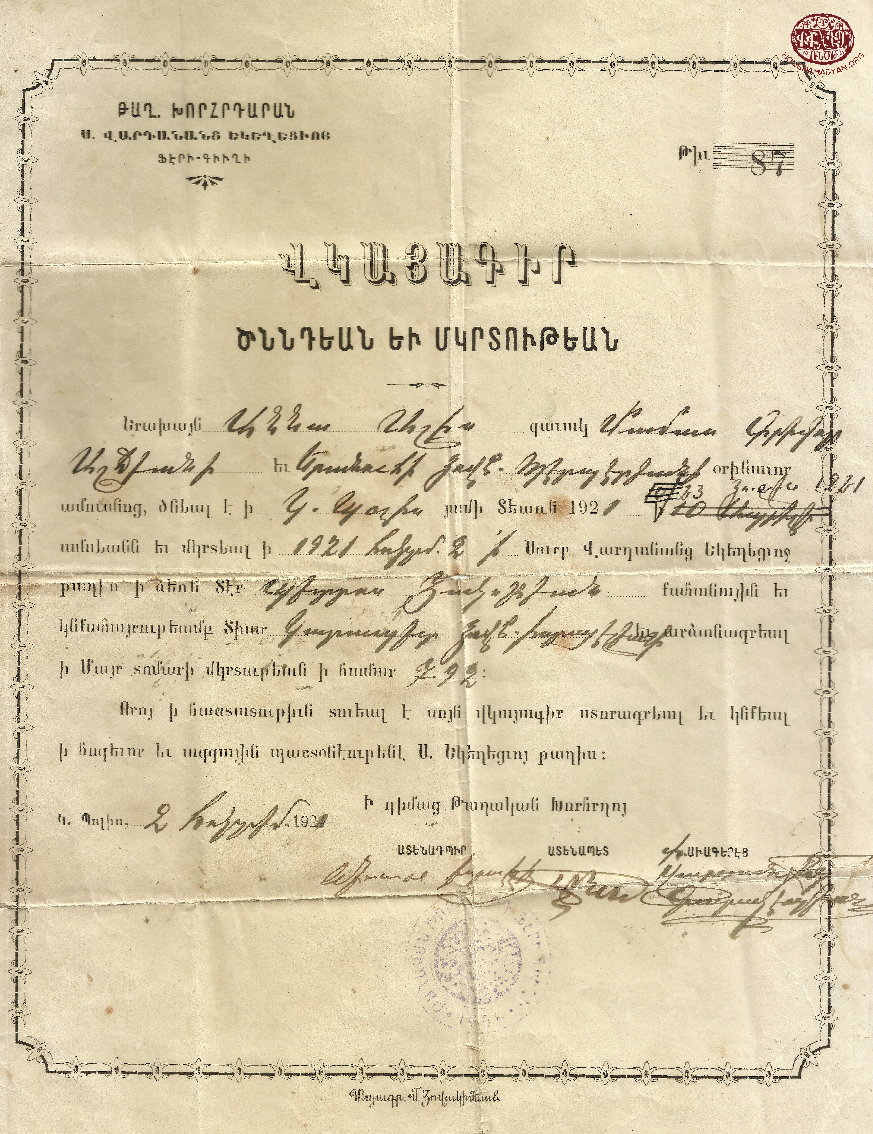

They all lived in Kirkor’s family house during the War, in Konya’s Çifte Merdiven Mahallesi, No 207. This was a big house built of stone with an interior courtyard. This was where the first two children of Mamas and Yeranouhi, Gorun/Garyun Jirayr (1915-2001) and Verjin (1916-2008) were born and later baptized by a travelling priest. During those years, Yeranouhi’s sister, Zarouhi Berberian, spent time teaching all the children of the family to read and write Armenian.

The house was right across the “Teachers college for Girls” (Konya Darü’l-Muallimat, established in 1915), and very close to the “Mevlevihane” (Whirling Dervish Hall). Some dervishes were accustomed to visiting in order to get some meals. The dervishes would come and sit in front of the house and wait. When someone from the household noticed the dervishes, they would be invited into the courtyard. Each were known by their names and had their personal napkins at the Ashjians’ home. They would sit down on the floor and wait to be served.

The Ashdjian family, on a pilgrimage in Jerusalem, March 1905. This photograph was taken in the courtyard of the Armenian Saint James Monastery. Standing, first from the left, is Mamas Ashdjian, seventh is Anna Ashdjian (nee Avakian), eighth is Krikor Ashdjian, and ninth and tenth are Elmas and Ohannes (from the village of Gümüşhacıköy, west of Marzvan/Merzifon). Most probably, the others in the photograph are other Armenian pilgrims who had come to Jerusalem from various parts of the Ottoman Empire. Notably, the young man sitting on the ground, on the very right, has his sleeve rolled up, and is displaying a tattoo of a cross. Many of the others are holding prayer beads, which they presumably purchased in Jerusalem.

Embroidery preserved by the Ashdjian family.

Unfortunately, there are no photos of that house. In 1961, Verjin traveled back to Konya to visit relatives still living there and to see the house. While there are a couple of photos from that trip, the house was not photographed. Verjin and company went to the house and rang the doorbell. A woman answered and upon learning who the callers were, turned pale. She yelled to her husband: “Bey! Bey! I had told you about my dream, I knew they would come!”. Verjin explained, she only wanted to visit the house where she was born, and that she had no other intentions. The woman served them coffee, and they left. This may be the reason why they did not take pictures of the house, thinking it might make the residents anxious. We presume that the house and twenty-five acres of land that used to belong to Kirkor Ashdjian was confiscated by local authorities, and later given to a certain Necibe Hanım when Kirkor Ashdjian was no longer actively living in the house.

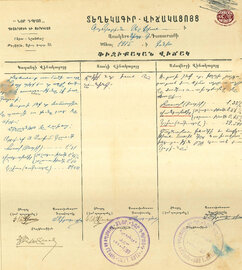

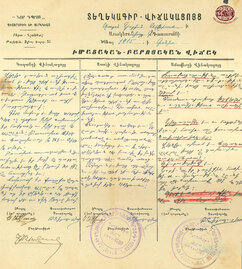

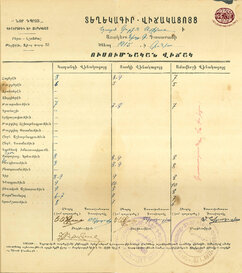

Goryun Ashdjian’s academic report cards from the 1924-1925 school year, when he was a student at the Nor Tbrots [New School] boarding school in the Nişantaşı neighborhood of Istanbul. Under “physical health,” the report notes that Goryun is “Generally healthy, but must improve his chewing in order to preserve his health. We are happy to report that he takes his naps on time and enjoys them. He is scared of insects.”

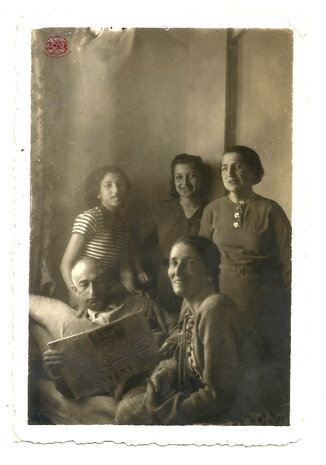

At the end of the WWI, Mamas, Yeranouhi, Zarouhi and the two children traveled back to Istanbul. Initially, they settle in Yeranouhi’s older sister Arousyag’s flat in Kurtuluş (Tatavla Avenue No.4 – Now Kurtuluş Avenue). That’s where Alis Anna (1921-2018), their last child, was born.

Mamas started a business of importing millstones. He had a shop in Sirkeci. Zaruhi helped him manage the accounting of that business as well as other tasks. She never married. It was Mamas who denied some candidates who wanted to marry her saying, “I’m taking care of you, why would you need to get married?”.

Yeranouhi became ill with tuberculosis, and she sometimes stayed at a sanatorium.

Alis, Mamas’s youngest and favorite, accompanied him on business trips abroad when she grew up. Verjin’s daughter, Eva, Mamas’s granddaughter, would recollect her childhood memories of the shop; it was at the corner of a street with wide display windows and huge millstones on display. That building does not exist anymore, as it has been demolished to expand the street.

In the 1920’s, Arousyag’s husband Hagop Hovikian died of an illness, and his family encouraged her to join her brother Haig who was then living in Paris. She left Istanbul in 1925, accompanied by her two, young children. Later both Haig and Arousyag were considered “deserters” by the Turkish authorities, and their shares in family belongings such as the house, shop and land in Ortaköy were taken by the General Directorate of Endowments (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü).

Mamas moved to the Belle-Vue building at the other end of the Tatavla Avenue with his family. It was from this new residence where they witnessed the big fire of Tatavla in 1928, after which many of the street names of that district were changed. In her nineties, Alis re-counted how, their building having been on top of a hill, saw the fire burn, felt its heat from her room, and could hear people screaming through the night.

At that time, Goryun had started school at Nor Tbrots (New School) in Istanbul – and although their home and school were close, he stays at school on weekdays, which he apparently didn’t enjoy. He only came home for the weekends. Later, he attended École Jeanne d’Arc (Today’s Saint Michel). It is not clear which primary school Verjin attended, but later she is sent to Notre Dame de Sion followed by Sainte Pulcherie. Alis went to École Moderne and Sainte Pulcherie, but she, being a child who was often ill, ended up getting private lessons from Mademoiselle Louise Mille who was a teacher at École Jeanne d’Arc. By this time, they had moved to a flat at Arpa Suyu Street, next to École Jeanne d’Arc.

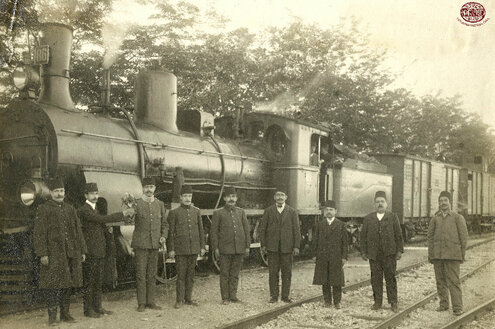

In 1922, Maryam’s husband Sebouh Yaghmourian/Yağmuryan was in trouble, and Kirkor Ashdjian was unable to help. He used to say “It would have been too obvious if I had done something for him as well." Sebouh worked for the railway company in Konya as head of the train station. He was told by people who knew him that he was “attracting too much attention,” whatever that meant, and thus he was asked to go to Kayseri for a while. He had his youngest daughter Adel yet in the cradle at this time, and as he left by train, the last thing he said was to ask his wife to take good care of the children. A few days later some people brought word to Maryam that it was cold in Kayseri and that someone asked Sebouh for his coat and some money. He was not heard from again.

Around 1925, Mamas decides to move his sister Maryam and her four children (Armenouhi, Valantin/Dirouhi, Jirayr, Adel) from Konya to Istanbul since it had been a couple of years that she had not received news of her husband. He got them settled in Berberian’s house in Ortaköy. Kirkor and Anna Ashdjian were also travelling back and forth between Konya and Istanbul, but as Kirkor’s health deteriorated, they stayed in Istanbul. 1927 was a sad year as Maryam’s eldest daughter Armenouhi died, followed by Kirkor, a few months later. Maryam, not wanting to stay in that house anymore, moved to Kurtuluş.

Lousaper and her family remain in Konya. She was married to Hovsep Kazandjian/Kazanci and had four children: Hnazant (1905-1967), Rapig (Rebecca, 1907-2000), Hrant (1913-1961), Roza (?-1977). Lousaper died in 1955 and is buried in Konya, but later, her daughter Rapig felt it was not a safe place for her to rest and got official permissions to bring her remains to Istanbul. Her grandchildren moved to Istanbul only around 1970.

After Kirkor’s passing, Anna initially stayed with Maryam and her children for a little while. Later, she lived with Mamas’ family. She was a quiet and reserved lady who didn’t seem to appreciate her son’s wife much. Later, she lost her ability to walk and spent her days in her room. Eva remembered she always wore a small apron with a pocket where she kept her cigarettes (Gelincik) and smoked often. She died in 1951. Two months after her death, Mamas died after a period of illness where he even travelled to Austria with Alis to seek treatment. Yeranouhi lived two more years and died in 1953.

Goryun, studied in France with Haig’s sponsorship, at École Breguet. Back in Istanbul, at some point he partnered with Verjin’s husband, who were both engineers. But Mamas requested that they get a Turkish partner with 51% of shares to assure protection if there was a case of “varlık vergisi” (the Capital Tax, a tax mostly levied on non-Muslim citizens in Turkey in 1942) again. A few years after Mamas’ death they went bankrupt. Goryun moved to Canada with his wife and wife’s daughter from a previous marriage. He spent the rest of his life there until his death in 2001. He had no children.

Verjin was a housewife. She was married to Onnik Akçeli, an electromechanics engineer who worked on big projects such as the illumination and climatization projects of Anıtkabir, the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Ankara. She had three daughters. She died in 2008.

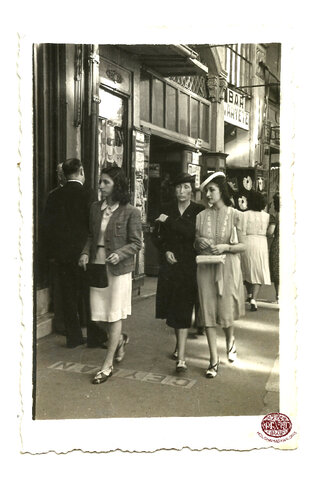

Alis, follows the classes of Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu at the Fine Arts School of Istanbul; she is part of a group of painters called “Onlar Grubu”. After the death of her father and Goryun moving to Canada, she wanted to move to France. She returned to Istanbul after two years spent in Paris. In late 1950s, she became Robert Anhegger’s assistant, the one who established the Goethe Institute of Istanbul. She worked there until she retired in 1993. In 1961, she married Arif Keskiner, a movie producer. Their marriage witnesses are Robert Anhegger, and Yaşar Kemal, the author, but the marriage ended in divorce ten years later. She had no children. She died in 2018.

Zaruhi lived with Verjin’s family until her death in 1971.

I’m An-su, great-great-grand-daughter of Kirkor Aşçıyan, grand-daughter of Verjin. I’m a translator and illustrator. I live in Istanbul and keep researching about the family history…

- ARABACI Caner, AYHAN Bünyamin, DEMİRSOY Adem, AYDIN Hakan, Konya Basın Tarihi, Konya, Palet Yayınları, 2009.

- KURTULGAN Kürşat, Konya’ya İskân Edilen Arap Mülteciler (1920-1928), Gazi Akademik Bakış, pp 129-136, Cilt 5, Sayı 10, Yaz 2012 (https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/73915)

- TEOTIG, Baskı ve Harf, Ermeni Matbaacılık Tarihi, İstanbul, Birzamanlar Yayıncılık, 2012, p.140

- Annuaire Oriental, commerce, industrie, administration, magisture de l’Orient 1913, p.1604 (https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/2878 )