A Historic Armenian Map’s Restoration Journey During the Pandemic

Author: George Aghjayan, 21/09/2021 (Last modified: 21/09/2021)

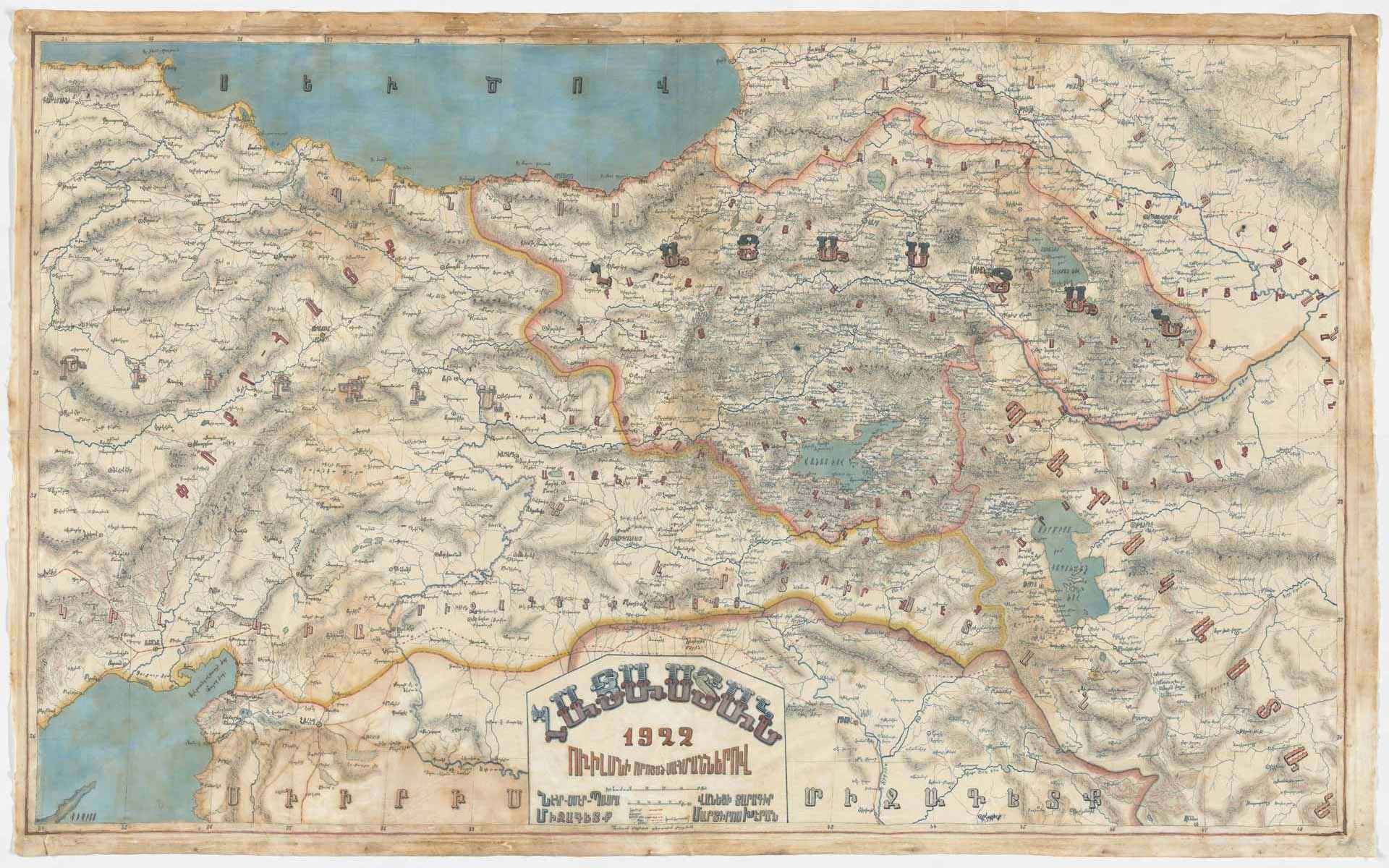

For years, every time I was on the 4th floor conference room in the Hairenik building, I would stare at a huge map on the back wall.. The 5’ x 8’ map was hand-drawn by Mardiros Kheranian in 1922. Those of us fortunate to have seen this map could not help but be drawn to it and get transported to the many Armenian villages it identified. Kheranian’s map is even more of a cultural and artistic treasure in a world where the Turkish government has attempted to wipe the names of these villages from modern maps.

Kheranian was born in the city of Van. He was a cartographer and teacher at the famed Armenian monastery of Varakavank. He participated in the defense of Van in 1915 and, after the genocide, he moved to Syria, where he continued to teach. We do not know the exact number of maps he produced during those years, but there are at least three others that we know of. These include a map of the defense of Van city which is reproduced in “The Armenian Highland: Western Armenia and the First Armenian Republic of 1918” by Matthew Karanian, his great-nephew. The Hairenik map is the oldest and largest of those known to exist.

Over the years, I had taken many images of the map with my camera, none of which were satisfactory. The condition of the map, its large size, and the glare from the protective glass covering it made it difficult to photograph.. At some point in its history, the map had sustained water damage. In addition, the cloth map had been stretched and stapled to a piece of plywood, which wasn’t ideal from a preservation perspective.

At the beginning of last year, I contacted Levon Avdoyan, the now-retired Armenian specialist at the Library of Congress, seeking his advice on conserving the map. He suggested I reach out to the Harvard Map Library.

Through the Harvard Map Library, I was put in contact with Louise Baptiste of Paper Conservator. On the eve of the pandemic, we were able to meet at the Hairenik and discuss restoring the map. The objective was to restore the damaged portions, clean the map of all harmful chemicals accumulated over the years, and make a high-resolution archival quality scan of the map. Louise recognized the importance of the map and enthusiastically took on the project.

When the day came to take the map out of the frame and roll it up for transport, I was nervous. Louise delicately removed the staples and placed the map between the necessary sheets and specifically designed roll to ensure its safe-keeping. For the first time in a long time, the map left the Hairenik building.

Over the past year, Louise painstakingly restored the map to its original grandeur. Along the way, she shared images and video of the work being done on the map. The process was complex. She made special screens to allow for vacuuming the map without causing damage. In addition, she had to find the right mix of chemicals to clean the map without removing the original ink. A year later, the map, now restored, was brought to the Harvard Map Library for scanning.

Robert Zink, a photographer for the Digital Imaging and Photography Services department of Widener Library at Harvard University, used an ~63 megapixel camera (one of the highest resolution cameras on the market today) to take 8 separate images of the map. The map’s size required this many images in order to maintain the desired resolution. There are then two ways to join these images to recreate the map in its entirety. The preferred way is to “stitch” them together so that the resulting full image is seamless to the viewer, without any misalignment, distortion or tone/color difference between sections. If this was not possible, then the images would have to be tiled. Stitching is most easily done with material (such as paper) that can remain flat and stable. With linen there is the possibility of the fabric stretching or misaligning between scans. We were very fortunate that with our map, stitching proved possible, and the results are phenomenal!

The map has now been returned to the Hairenik, awaiting the new frame that will protect and preserve it. The entire project was made possible by grants from the Armenian Cultural Association of America and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. The digitized map will be made freely available through Houshamadyan: A project to reconstruct Ottoman Armenian town and village life.