Kaza of Shirvan – Demography

Author: Tigran Martirosyan, 07/06/2023 (Last modified: 07/06/2023)

A mountainous and forested area extending north-east of Sgherd (Siirt), the chief town of the same name as the sandjak (prefecture) in the vilayet (province) of Bitlis, Shirvan, also called Shervan, Shervank or Sherwan, during the late Ottoman era was a kaza (county) of the sandjak of Sgherd bounded on the north by the kaza of Bitlis, the central county of the same name as the sandjak in the homonymous vilayet, on the south by the Eastern Tigris (Bohtan, Bohtan Su or Botan Çayı) River, and on the west by Kharzan, another kaza of the Sgherd sandjak. According to one theory, the county’s territory for the most part overlapped that of Argastovit gavar (county) of the Mokq (Moks) ashkhar (province) in the Kingdom of Greater Armenia. [1] Another theory places Shirvan in Aghdzn (Arzn) or Ketik gavars of the Aghdznik ashkhar of the ancient Armenian kingdom. [2] In terms of population size, Shirvan on the eve of the Armenian Genocide in 1915, was least densely populated by Armenians compared to other counties comprising the sandjak of Sgherd. [3] Yet, the county was reported as being “an Armenian speaking” [4] area compared to other kazas with mixed population.

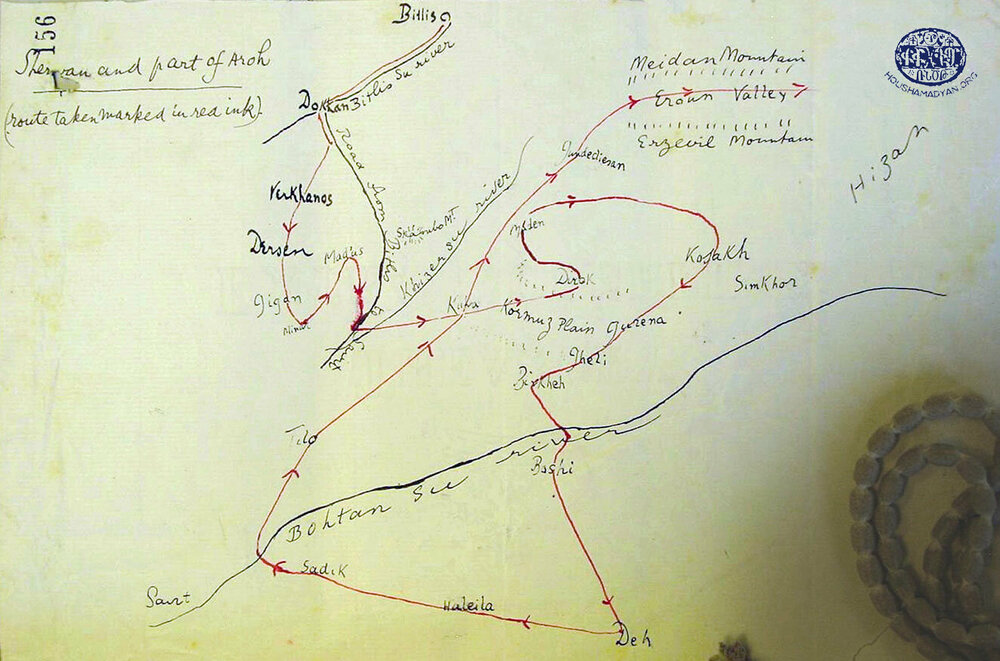

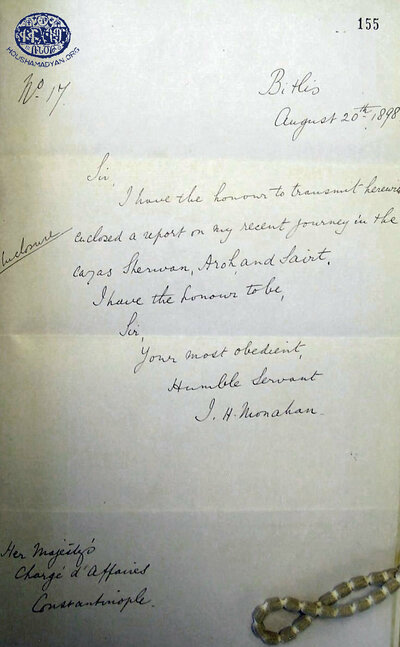

James Henry Monahan, British Vice-Consul in Bitlis, who journeyed to Shirvan in 1898 and visited all the Christian villages of the kaza except four small ones, described Shirvan as a mountainous county that had “two fairly open plains between the mountains” and was “famous for its vines, though little wine or raki was ever made of it. Pomegranate and fig trees abound in the southern half of the kaza, and walnut and pear trees all over it.” [5] Aristakes Tevkants, an Armenian folklorist, who journeyed to Western Armenia in 1878, wrote that “in Shirvan the finest goldmine is found, whose existence the locals keep a secret from the government to avoid unnecessary trouble.” [6] British Major Francis Richard Maunsell, who visited the highlands of Kurdistan and “the broad Armenian plateau north of Lake Van” in 1901, concurred that in Shirvan “there were ancient disused goldmines.” [7]

According to Monahan, “except the chief village Kyufra […] and one large village Minar, there were no mixed villages, that is to say, villages now inhabited by both Christians and Mussulmans.” He added that there was “no Christian school in the whole of Shirvan, and of Muslim schools none but a few very small Koranic schools.” The British Vice-Consul noted that the local population in general had “remained more ignorant and backward than those of any part” of the vilayet of Bitlis outside the Sgherd sandjak. [8]

Throughout most of the nineteenth century, Armenians and Syriacs of Shirvan have become victims of an oppressive tax-farming system imposed on them by local authorities. These two Christian ethnic groups were subject to further exactions by both local Kurdish chieftains and the marauding Kurdish nomads. Having no strength left to bear these sufferings, many Armenian and Syriac peasants were leaving their homes and villages in search of work in other parts of the country, migrating for extended periods or permanently. The migration, which apparently was already extensive before the 1880s, had an adverse impact on population growth. Locals told occasional travelers’ stories of a glorious past of the land, when their villages were more populous and flourishing. [9]

In November 1895, Shirvan “became of the whole vilayet, perhaps the worst scene of plundering and of forced conversion [of Armenians and Syriacs] to Islam.” At the time of Monahan’s visit, whose purpose was to gather information that might shed light on the atrocities perpetrated by the Kurds, the Armenians and Syriacs “had been almost all reconverted” to Christianity. [10] Acts of plunder and forced conversion were accompanied by massacres that reduced the size of the Armenian population of Shirvan. Monahan reported that 151 Armenian men and 18 women were killed. [11] Apparently, forced Islamization of Armenians and Orthodox Syriacs living in Shirvan continued throughout the Hamidian massacres and has been reported to be taking place as late as 1897. [12] According to Kévorkian & Paboudjian (1992), the villages of Derzni, Daraban, Minar, and Matar (see the village list below) were emptied of their Armenian inhabitants during the massacres of 1895-1896. [13]

Located near old, abandoned mines and saltworks, Kyufra, “a dusty backwoods village,” [14] otherwise called Shirvan-kale, was the administrative center of the kaza [15] with a mixed population of Kurds, Syriacs, and Armenians. Lieutenant Justin Shiel, an Irish army officer and diplomat, reported during a journey to Sgherd in the summer of 1836, that Kyufra (Shírván in Shiel’s text) was “a flourishing village of about 200 houses.” [16] Vital Cuinet, a French geographer, referred to Kyufra as a “small town” that in 1891 had only 130 households. Monahan estimated that in 1898 Kyufra had 50 households, of which 17 were Christian—4 being Armenian and 13 Orthodox Syriac. The Sgherd Prelacy of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople counted 5 Armenian, 12 Syriac, and 50 Muslim households in the village in 1902. A census carried out by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1913-1914 identified Kyufra as a village of 80 households, including 1 Armenian, 39 Nestorian Syriac and 40 Kurdish.

Monahan suggested that the remains of an ancient bath and marketplaces in Kyufra showed “that the village was once a town of some importance.” [17] The village reportedly contained the ruins of an ancient fortress. [18] Carl Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt, a German orientalist and historian who journeyed to Western Armenia on a research trip in 1898 and 1899, concurred that Kyufra (Küfrä in Lehmann-Haupt’s text) was “a village and castle (in German, Dorf und Schloß), which [stood] on a high rocky cone above a plain.” [19]

However, from the late Middle Ages until the late eighteenth century, the most populous and vibrant settlement in Shirvan was Zrekan, also called Zrekhan or Zeregan (Turkified to Zerki), the chief town of the homonymous principality and then a village group, called nahiye in Turkish. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, this town, also appearing in data sources as Deyrazinar or Deyr Azinar, had 700 predominantly Armenian households. Slightly to the north of the town stood an ancient crumbling fortress housing ruin of a monastery. In the mid-nineteenth century, Zrekan was destroyed and deserted, and the obscure hamlet of Derzni (see village list below), which apparently took its name from Deyrazinar, emerged in its place. [20] Several formerly Armenian populated villages in the village group of Zrekan, such as Bemla [Geçit], Gundik (Gundo) [Gündoğdu], Nerban (Nerpan) [Obalı], Havel (Havelanc) [Çınarlı], Rechle [Tanrıyar], Rechlai [current name unknown], Haronk [current name unknown], and others, were also destroyed and deserted during the said period. [21]

Because in the fifth and sixth centuries, the Sassanid dynasty that ruled the Persian Empire pursued discriminatory religious practices against the Armenian Apostolic Church, segments of the Armenian population of several southern and south-western gavars of Greater Armenia converted to Nestorian Christianity. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for rare travelers to Shirvan (indeed, “most of the county,” as attested by Monahan, seemed “never to have been previously visited by any European” [22]) to encounter several settlements containing Armenian Nestorian households. Shirvan was also home to a large number of Armenian speaking Nestorian Syriacs. These were mainly concentrated in the localities in the village group of Eroun adjoining the kaza of Khizan (Hizan) in the vilayet of Bitlis, such as Avav, Potki, Gndzik, Derik, Halndzé [Bardacık], Saaz [Yelkıran], Serous (see village list below), and a few others. [23]

Until the late Middle Ages, Armenians and Armenian speaking Syriacs constituted a large proportion of the population of Shirvan, exemplified by the fact that many of the place names in the county bore unique ethnic connotations. [24] By the late nineteenth century, however, Shirvan has become a largely Kurdish populated county. While by that time quite a few Kurdish groups have become sedentary and a number of villages in the kaza inhabited yearlong, Shirvan was also a favorite destination to several nomadic Kurdish tribes, which used the high mountain meadows in the summer and wintered in lower areas outside the kaza.

A sizeable portion of Christian village populations in Shirvan were also Orthodox Syriac. Because a segment of these Syriacs was Armenian speaking, their ethnic origin was not always recognized in Armenian sources of the time. [25] A Syriac priest, whom Irish geographer Henry Lynch met during his short sojourn in Bitlis in the late-1890s, concurred that “some Syriacs had emigrated, while the greater number had become Armenians.” When Lynch enquired “why the faithful remnant spoke Armenian to the exclusion of any Syriac dialect,” the priest replied, “because this earth is Hayasdan [Armenia].” He added that there were some 1,500 Syriacs in the sandjak of Sgherd, mostly in the kazas of Sgherd and Shirvan. [26]

Until about 1860s, there existed an autonomous principality in Shirvan, called hükümet in Turkish, which extended south of the town of Bitlis, covering the territory of Shirvan proper and several outlying areas. [27] Cuinet reported that in 1891 there were 207 total localities and that of 14,168 inhabitants 9,655 were Muslim, mostly Kurds, 4,113 Armenian, and 400 Orthodox Syriac. [28] In a statistical pamphlet published in 1904, Russian General Staff Colonel Vladimir Mayewski disagreed with Cuinet’s estimate with regard to Armenians amounting to 29 percent of the total population in Shirvan, stating that only two out of 25 villages he had visited in the late 1890s were Armenian populated. Mayewski added, however, that he was only able to visit localities situated in the western sector of the kaza. [29] The early twentieth-century Ottoman atlas titled “Memâlik-i Mahrûse-i Şâhâneye Mahsûs Mükemmel ve Mufassâl Atlas” and published in Arabic script, counted 160 total localities in 1907 in Şirvan Merkez (Shirvan Central) and the kaza’s three nahiyes, which the atlas identified as Menar, Hasras, and İskanbo. [30]

In an editorial covering the killings and forced Islamization of the Armenians of Shirvan during the Hamidian massacres in 1895, Ararat, an Armenian journal published in Etchmiadzin, suggested that there were 20 Armenian settlements in the county. [31] According to Monahan, Shirvan had about 200 villages, most of them consisting of six households or less. Of these, only 28 were Christian, 10 Armenian and 18 Orthodox Syriac, but they were much larger than the Kurdish ones. The Ottoman government annual for the vilayet of Bitlis, called salnamé, published four years prior to Monahan’s travel report, counted 13,420 Muslims and 2,307 Christians. According to British Vice-Consul’s calculation, there were “3,048 Christians reckoning six persons to a home, and about four times as many Muslims, including the three nomadic [Kurdish] tribes Mehmediyan, Usturikan, and Dimili,” which were always in the kaza and which numbered “in all about 4,000 souls.” [32]

However, indications from various primary sources suggest that the average household size in rural areas similar to Shirvan was almost certainly greater than six. Because these sources differ on the average household size in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, which had a considerable population of ethnic Armenians, in this study, eight will be used as an average number of members per household in rural areas, as suggested by Bishop Vahan Ter-Minassian (Partizaktsi), a Commissioner at the Patriarchate in the 1860s and 1870s. [33] That being said, twenty will be used as an average number of households per village for the vilayet of Bitlis, as suggested by Mayewski. [34]

The attacks by Kurds from Atmanikan, Motikan, and Dimbilan tribes in November of 1895 [35] during the Hamidian massacres, were a severe blow to the Armenian and Syriac populations of Shirvan. The systematic and thorough plunder to which they were subjected had deprived them of means to produce. As a result, hunger and food insecurity, as well as inability to pay onerous taxes, drove many Armenians and Syriacs to flee their native lands throughout and after 1895. According to one estimate, from 22 Christian villages in the county, more than 50 percent of the population had fled. The 1895 massacres constituted an important but often unrecognized phase in the Kurdification of Shirvan, a process that weaved a new, heavily monoethnic, demographic fabric of this once ethnically diverse and culturally rich kaza. [36]

If, according to the administrative structure of the vilayet of Bitlis in the late-nineteenth century, Shirvan until 1896 had one nahiye of Zrekan (Zerki), beginning from 1897 the kaza comprised of three nahiyes. [37] In 1900, an editorial in Byurakn counted 3,000 Armenian inhabitants in Shirvan. [38] In 1910, an editorial in Azatamart reported 39 total villages in Shirvan Central, 39 in Minar, 40 in Hasras, and 42 in Sgambo (the latter three being nahiyes corresponding to Menar, Hasras, and İskanbo as spelled out in the Ottoman atlas “Memâlik-i Mahrûse-i Şâhâneye Mahsûs Mükemmel ve Mufassâl Atlas”), [39] amounting to 3,200 households or 25,600 inhabitants, if the average numbers of households per village and members per household suggested by Mayewski and Partizaktsi are applied.

On the eve of the First World War, Shirvan had a mixed population, consisting of Kurds, Armenians, and Syriacs. A census carried out by the Patriarchate in 1913-1914 produced a figure for Armenian populated villages at 15 (including one Armenian household in Kyufra), and the number of households at 173. The number of inhabitants was placed at 1,683, excluding the unspecified number of inhabitants in one household in Kyufra and a number of Armenian speaking Nestorian Syriac households in Gondegizan (see village list below). [40] Apparently using the updated Patriarchate census data available to them, Kévorkian & Paboudjian placed the number of villages in 1914 at 19, and the number of the Armenian population at 2,853 living in 317 households. [41]

A census carried out by the Ottoman state before the war, placed the number of Muslims in Shirvan at 15,181, Armenians at 1,169, and the Syriacs at 1,109. [42] Another Ottoman source found in a Turkish collection of archival documents, revealed that in 1915 the number of Armenians inhabiting Shirvan, who were to be “relocated and transferred,” as the source chose to call forced deportations to deserts in southern vilayets, was recorded in Ottoman registries at 1,144. [43] Published by the Turkish General Staff, these registries were drawn up after the Ottoman government on May 31, 1915 (Decree No. 326758/270) had decreed “relocation and transfer” of the Armenians residing in areas near the frontlines because, in the view of the authorities, they “were jeopardizing movements of the Ottoman army units committed to defending the Ottoman borders against enemy forces.” [44] Although the Armenian peasants of Shirvan had no intention to “jeopardize” the movements of the army units, most had vanished, and their fate remains unknown. It is hard to imagine that most of them were spared killings and death marches during the genocide. The Syriacs from the villages across Shirvan, both Catholic and Orthodox, representing a segment of the total population of 5,000 Syriacs living in the sandjak of Siirt, received the same treatment as the Armenians. [45]

According to unconfirmed reports, out of the total number of Armenians living in Avav, Avin, Djouma, Gndzik, Halndzé, Nebayn, Serous, Sermet, and Siserk (see village list below), only about 90 villagers had survived, mostly women and children. This situation appears to have been typical of most other Armenian populated areas of Shirvan during the genocide. Those Armenians of Shirvan who were fortunate to escape Ottoman annihilation, fled to Khizan and, during the summer of 1915, settled in the villages throughout the Salmast (Salmas) county in Persia. However, in May 1918, they had to flee Persia and migrate to British-controlled Mesopotamia (Iraq). A refugee count carried out by the Armenian Relief Committee of Mesopotamia in August 1919 in the tent camp at Baqubah, a town just north-east of Baghdad, in which the Armenians who found refuge in Iraq were kept, produced a figure at 85—all Armenians of Shirvan from the villages of Avin, Gorinan, Derik, Sermet, and Smkhor. [46]

For this study, several Armenian sources were used covering a period of 37 years, or from 1878 to 1915. Because these various sources provided discrepant and oftentimes conflicting demographic data, it has not seemed realistic to determine the most approximate Armenian population size of Shirvan. Nor does it seem possible to make such an attempt given large data discrepancies. The sources used for this study, in the order of their publication dates, are listed below. Tadevos Hakobyan, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan, authors of the “Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories,” testimonies of various genocide survivors in the collection of documents edited by Amatuni Virabyan, [47] and periodicals Ardzagank published in Tiflis, Byurakn and Azatamart, both published in Constantinople, supplied additional data.

- The travel report by Aristakes Tevkants published in 1878;

- The 1898 travel report by James Henry Monahan, British Vice-Consul in Bitlis, which represents one of the few sources available for Shirvan in the late nineteenth century;

- The Statistical Report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902;

- The 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census figures reproduced in Kévorkian & Paboudjian (1992);

- The brochure written in 1912 by Armenian statistician A-Do (Hovhannes Ter-Martirosian); and

- The book about the sufferings of the Armenian clergy during the genocide composed by writer Teodik (Teotoros Lapjinchian) in 1921․

In the earliest primary account used for this study, Tevkants reported nine entirely Armenian populated villages and four villages with ethnically mixed population in Shirvan in 1878. He suggested that the total number of Armenians in these localities amounted to 1,569. However, if the number of inhabitants is calculated on the basis of the breakdown of village populations found elsewhere in his travel report, the number of Armenians would total 1,622. [48]

The anonymous author of the article “Namak Sghertits” (A Letter from Sgherd) published in Ardzagank, suggested that in 1882 there were 116 villages or 14,092 inhabitants in Shirvan, of whom 1,569 were Armenian living in nine villages, 11,590 Kurdish, and 933 Syriac. [49] The 1892 Ottoman salnamé for the vilayet of Bitlis counted 15,729 inhabitants, of whom 13,420 were Muslim, 1,438 Syriac, 109 Copts, and only 760 Armenian. [50] This latter figure is improbably low. In the statistical study published in 1904 by Vladimir Mayewski, which covered household counts in the vilayets of Van and Bitlis from either 1890 to 1897 or 1899, [51] the Russian Colonel placed the total population number at 15,584, of whom 4,524 were Armenians, 10,620 Kurds, and 440 Orthodox Syriacs. [52] The 1902 Statistical Report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy identified 13 Armenian localities that contained 155 households before 1895, and 15 additional localities for which no household count was provided. [53] This would place the number of Armenian inhabited localities in Shirvan before 1902 at 28.

In the years immediately preceding the genocide, A-Do identified 14 villages containing 340 Armenian households. This would place the number of Armenian inhabitants at about 2,380. A-Do provided data he had extracted from a bulletin issued by the Catholicosate of Aghtamar [54] that apparently contained a household count. [55] Teodik reported nine Armenian localities or 120 households in 1914. [56] This would place the number of inhabitants at 960. Remarkably, Teodik reported the smallest population of Armenians. The number he had produced is not supported by any other Armenian source and is, without doubt, an underestimate. The motives that underlay Teodik’s statistics remain unclear.

Listed below are the localities in Shirvan, which were reported by the data sources as being largely populated by Armenians or had a number of Armenian households or were formerly inhabited by Armenians, along with their present-day Turkified names placed in brackets. [57] Because of ambiguously demarcated county borders, several localities on the Sgherd Prelacy’s village list, according to other data sources, most likely formed part of the Hizan and Gyozaldara kazas in the sandjak of Bitlis. These localities, such as Sifor, Sok, Sap, Halndzé, and a few others, were reported by the Sgherd Prelacy as formerly Armenian-inhabited villages which, by 1902, were destroyed and deserted․ In cases where identification of the current names of mezras, Arabic for “hamlet,” which were typically situated near larger villages, was not possible, a text appearing in square brackets will specify that the locality is a mezra of a particular village.

Avav, Havav, Havou [Gürgencik]

38° 8'41.62"N, 42°16'4.98"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 10 households, Hakobyan et al. listed this village as an Armenian populated locality affected by the massacres in 1895. Unless there was a different locality by the name of Avar, Monahan supposedly referred to Avav as Avar and described the settlement as a “large village” which had 36 mixed Armenian and Syriac households.

Avin, Havin, Hviyn [Kayalı]

38° 9'16.92"N, 42°13'53.77"E

Tevkants: 162 inhabitants, Hakobyan et al.: 20 households in the mid-nineteenth century, Sgherd Prelacy: 15 households in 1895, which was higher before the massacres․

Baytaroun, Beytaroun, Beyt Harun, Peyt-Harun [İkizler]

38° 3'54.38"N, 41°55'38.16"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 10 households in 1895 (more than 100 households during an unspecified prior period), Patriarchate: 4 households or 35 inhabitants, Teodik: 3 households.

Berk, Birke, Birkheh, Perk, Perg, Prke, Perke, Birki [Yatağan]

37°58'48.21"N, 42° 8'58.49"E

Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Birkeh, as a “little Armenian village” which had 14 households in 1895, but at the time of his visit only 6; Sgherd Prelacy: 8 households (25 households before 1895), Hakobyan et al.: 13 households in the early twentieth century, A-Do: 13 households, Patriarchate: 5 households or 46 inhabitants.

Daraban, Derraban, Darabani, Darabun, Terrapan, Tarap, Direban, Deraba, Direbun [Dokuzçavuş]

38° 4'31.77"N, 41°50'38.57"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 10 households in 1895․

Deravel, Deravil, Derbal, Derhavil, Teravel [current name unknown, possibly a mezra of Yarımtepe]

38° 4'47.24"N, 42°13'1.48"E

Hakobyan et al.: 30 households in 1909, A-Do: 30 households Patriarchate: 22 households or 198 inhabitants․

Derik, Derek, Terek, Tereg, Dirik, Erouni, Irun [possibly Kayahisar]

38° 9'27.84"N, 42°13'35.86"E

This village of Derik, a locality in the village group of Eroun, is not to be confused with the homonymous village in Shirvan Central (Şirvan Merkez) below. To help readers distinguish between the two, this village of Derik until the beginning of the twentieth century housed the ruined Church of Surb Vardavar, otherwise known as the Church of Surb Etchmiadzin. [58]

Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Direk, as a “wretched little hamlet” consisting of 4 Armenian households; Sgherd Prelacy: 8 households in 1895 (40-50 households during an unspecified prior period), Hakobyan et al. listed this village as an Armenian populated locality, A-Do: 15 households, Patriarchate: 6 households or 53 inhabitants, Teodik: 7 households.

Derik, Derek, Terek, Tereg, Dirik [possibly Söbetaş]

37°59'42.60"N, 42° 9'0.45"E

This village of Derik, located in Shirvan Central (Şirvan Merkez), is not to be confused with the homonymous settlement in the village group of Eroun above. To help readers distinguish between the two, this village of Derik reportedly housed the Church of Surb Yeghishé.

Derzni, Derzen, Derzin, Derzıni, Tarzen, Terzen, Terzin, Deyr Zin, Zrekan, Zirkan [Adakale]

38° 7'50.89"N, 41°52'18.45"E

Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Dersen, as a settlement which “seems to have been a large place once,” consisting of three wards or quarters, one of which before 1895 had 13 Armenian and 9 Kurdish households; Hakobyan et al.: 20 households in the 1880s, Sgherd Prelacy: 20 households in 1895 (100-200 households before the massacres), Teodik: 3 households․

Djouma, Djoum, Choum, Choumek, Jum, Tchom, Chum [Kaval]

38°10'41.72"N, 42°17'8.88"E

Tevkants: 49 inhabitants, Hakobyan et al.: 16 households in the late nineteenth century, Sgherd Prelacy: 12 households, Patriarchate: 10 households or 89 inhabitants.

Gndzik, Gindzik, Ginzig, Gindzou, Zinzik [Oya]

38° 9'28.97"N, 42°14'37.08"E

Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Gunzag, as a “large village” which had 40 mixed Armenian and Syriac households; Genocide survivor Berkho Azoyan: 55 households or 600 inhabitants. It is at this village that, according to Azoyan, a British consul who visited the settlement sometime before the genocide, snitched the handwritten church bull, called kondak in Armenian, that bore the image of the Virgin Mary. [59]

Gondegizan, Gonde Gizan, Gondezian, Gondedizan, Gundedizan, Gyundidizan, Gunde-Deghan, Kondudizan [Suludere]

38° 8'0.34"N, 42° 6'7.78"E

Monahan described the village as a Orthodox Syriac settlement which before 1895 had 20 households, but at the time of his visit only 14; A-Do: 10 households, Hakobyan et al.: 20 households in 1914, Patriarchate: 15 Armenian-speaking Nestorian Syriac households.

Gorinan, Gyornan, Kourena, Kyurena, Kyurenan, Kyurinan, Kourinan, Kourina, Korena, Gyurinan, Gurana [other known names Gurena, possibly Gorihan]

This village may no longer exist. Approximate location: 37°59'12.90"N, 42°12'16.25"E

Tevkants: 320 inhabitants, Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Gurena, as an Armenian populated locality which before 1895 had 50 households, but at the time of his visit only 20; Sgherd Prelacy: 25 households (more households during an unspecified prior period), Patriarchate: 30 households or 270 inhabitants, Teodik: 38 households. For Gorihan, in case if it is another name of Gorinan, A-Do reported 50 households, and Hakobyan et al. 50 households in 1909.

Karve, Garve, Gyunt-Kevir, Gunde Kevir, Kyvr, Gundukevir [Taşlı]

37°59'25.31"N, 42° 8'24.52"E

Tevkants: 80 inhabitants, Hakobyan et al.: 7 households in 1909, A-Do: 7 households.

Kelin, Keli, Geli, Gili, Gelin, Gheli, Kelou, Kyaloum [Durankaya]

37°59'7.62"N, 42°10'48.18"E

Tevkants: 24 inhabitants, Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Gheli, as “a comparatively prosperous” Armenian populated locality consisting of 6 households; Sgherd Prelacy: 12 households (80 households sometime before 1895), Hakobyan et al.։ 10 households in 1909, A-Do: 10 households, Patriarchate: 8 households or 72 inhabitants, Teodik: 9 households.

Kevidjan, Kevizhan, Kevichan, Kavizhan, Gavadjan, Kevizhan [Yolbaşı]

37°59'15.31"N, 42°14'52.74"E

Hakobyan et al. referred to this village as a formerly Armenian populated locality which was destroyed and in the 1890s, apparently as a result of the Hamidian massacres, was already populated by the Kurds.

Khandak, Khantak, Khandouk, Khoundoukh, Khenduk, Khendek, Khentek, Hendek [İncecik]

38° 0'54.78"N, 42°19'3.90"E

Tevkants: 80 inhabitants; Monahan described the village, to which he referred as Hindik, as an Armenian hamlet of 4 households; Sgherd Prelacy: 3 households (15 households sometime before 1895), Hakobyan et al.: 20 households in 1909, A-Do: 20 households, Patriarchate: 10 households or 91 inhabitants, Teodik: 13 households.

Kigan, Kikan, Gigan, Kirkan, Krkanc, Gizan, Kighan [İkizler]

38° 6'32.86"N, 41°50'7.61"E

Monahan described the settlement as an Armenian village which before 1895 had 30 households, but at the time of his visit only 20; Sgherd Prelacy: 30 households (80 households sometime before 1895), Hakobyan et al.: 40 households in the early twentieth century, Patriarchate: 41 households or 369 inhabitants, Teodik: 41 households, Genocide survivor Hakob Grigorian: 60 households or 520 inhabitants.

Kyosakh, Keosakh, Kosih [İncesırt]

37°59'28.26"N, 42°15'56.77"E

Monahan described the village, to which her referred as Kosakh, as a Orthodox Syriac settlement of 32 households; Hakobyan et al.: 5 households in 1909, A-Do: 5 households.

Kyufra, Koufra, Kofra, Kfra, Kefra, Kyufre, Kufre, Kufra, Kafrah, Kfta, Shirvan, Sherwan, Shirvangalesi, Shirvankale, Shirvan kale [Şirvan]

38° 3'40.57"N, 42° 1'50.67"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 5 households, A-Do: 20 households, Patriarchate: 1 household, Teodik: 1 household․

Madan, Maden, Matan, Matin, Madenkoyu, Matenkoyu [Madenköy]

38° 5'45.15"N, 42° 9'17.82"E

Tevkants: 140 inhabitants, Monahan referred to this village as a Orthodox Syriac settlement; Hakobyan et al.: 30 households in 1909, A-Do: 30 households.

Matar, Madar [Sarıtepe]

38° 1'58.13"N, 41°48'10.73"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 10 households in 1895.

Mazoran, Mozoran [Özdoğan]

This village may no longer exist. The village was known under the name placed in brackets until the 1990s, when it was apparently destroyed. Approximate location: 37°58'40.27"N, 42°12'56.37"E

Tevkants: 162 inhabitants.

Merdj, Merch, Merche [Suluyazı]

38° 7'57.03"N, 42° 7'13.44"E

Hakobyan et al.: 10 households in the mid-nineteenth century, Monahan described the village as a Orthodox Syriac settlement which before 1895 had 9 households, but at the time of his visit only 2.

Minar, Menar, Mnar, Manare, Minarek [Dilektepe]

38° 4'50.94"N, 41°49'51.13"E

Monahan described the village as half Kurdish half Orthodox Syriac, Hakobyan et al. referred to this village as an Armenian settlement until the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Sgherd Prelacy: 3 households.

Mzre, Mzro, Mezro, Mzra, Mezre [Aktay]

The location of this village cannot be determined.

Tevkants: 56 inhabitants, Sgherd Prelacy listed Mezre as a formerly Armenian-inhabited locality that by 1902 was destroyed and deserted.

Nebayn, Nbayn, Nabayin, Noubayn, Nubain, Nebin, Napayen, Nepin, Napen, Nibin [Turgutlu]

38° 9'40.71"N, 42° 9'45.18"E

Tevkants: 160 inhabitants, Monahan described the settlement as an Armenian village which before 1895 had 40 households, but at the time of his visit only 7; Sgherd Prelacy: 12 households (more households before 1895); Hakobyan et al.: 50 households in 1909, A-Do: 50 households, Patriarchate: 135 inhabitants, Genocide survivor Khachik Vardanian: 40 households or 300 inhabitants.

Poukh, Pough, Poul, Pul, Pole, Polle, Bole [Köprü]

38°10'22.44"N, 42°17'23.66"E

Hakobyan et al. listed this village as a formerly Armenian populated locality which was destroyed and in the mid-nineteenth century was already populated by the Kurds, Sgherd Prelacy listed Poul as a formerly Armenian-inhabited locality that by 1902 were destroyed and deserted, Patriarchate: 5 households or 45 inhabitants.

Sematar [current name unknown]

The location of this village cannot be determined.

Sgherd Prelacy: 5 households in 1895.

Sermet, Sermerd, Sermert, Sirmet, Sermud, Sermit, Selmit [possibly Yamaç]

38° 8'2.81"N, 42°18'48.02"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 8 households in 1895, Hakobyan et al. listed this village as an Armenian populated locality until the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Serous, Sahrous, Sarous, Seruz, Serus [Kesmetaş]

38° 9'39.57"N, 42°12'29.59"E

Tevkants: 120 inhabitants, Hakobyan et al. listed this village as an Armenian populated locality until the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Shmelia, Shmilan, Shemelan, Shemaypan, Shumeylan, Shimilan [Sıvacık]

Possibly 38° 6'25.61"N, 41°55'25.30"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 15 households in 1895.

Siserk, Sizerk, Siserik, Sezers, Seze, Sedars, Seders, Seters, Sedres, Sitres, Sedjer, Setcher [Çayır]

38°11'1.38"N, 42°17'2.15"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 20 households (more households during an unspecified prior period), Hakobyan et al.: 40 households in the mid-nineteenth century, A-Do: 20 households, Patriarchate: 20 households or 181 inhabitants.

Smkhor, Semkhor, Simkhor, Simhor [Sarıdana]

37°58'21.67"N, 42°16'54.26"E

Monahan described the village as a Orthodox Syriac settlement and the largest Christian village in the kaza consisting of 50 households; Sgherd Prelacy: 5 households, Hakobyan et al.: 60 mixed Armenian and Nestorian Syriac households in 1909, A-Do: 60 households, Patriarchate: 5 households or 44 inhabitants.

Sorian, Serian, Sheryan, Shiryan [Koyacık]

38° 2'56.66"N, 41°47'54.04"E

Sgherd Prelacy: 8 households, Teodik: 5 households.

Zvzik, Zevzik, Zghzik, Zivzek, Zivzik, Zizik [Dişlinar]

37°58'18.81"N, 42°19'4.14"E

Tevkants: 11 inhabitants.

Names of the Armenian populated villages of the kaza of Shirvan in the Sgherd sandjak during the late Ottoman period. Their current Turkified names are mentioned between square brackets.

- Avav [Gürgencik]

- Avin [Kayalı]

- Baytaroun [İkizler]

- Berk [Yatağan]

- Daraban [Dokuzçavuş]

- Deravel [Yarımtepe]

- Derik [possibly Kayahisar]

- Derik [possibly Söbetaş]

- Derzni [Adakale]

- Djouma [Kaval]

- Gndzik [Oya]

- Gondegizan [Suludere]

- Gorinan [other known names Gurena, Gorihan]

- Karve [Taşlı]

- Kelin [Durankaya]

- Kevidjan [Yolbaşı]

- Khandak [İncecik]

- Kigan [İkizler]

- Kyosakh [İncesırt]

- Kyufra [Şirvan]

- Madan [Madenköy]

- Matar [Sarıtepe]

- Mazoran [Özdoğan]

- Merdj [Suluyazı]

- Minar [Dilektepe]

- Mzre [Aktay]

- Nebayn [Turgutlu]

- Poukh [Köprü]

- Sematar [current name unknown]

- Sermet [possibly Yamaç]

- Serous [Kesmetaş]

- Shmelia [Sıvacık]

- Siserk [Çayır]

- Smkhor [Sarıdana]

- Sorian [Koyacık]

- Zvzik [Dişlinar]

- [1] Hakobyan, Tadevos, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan. Hayastani ev harakits shrjanneri teghanounneri bararan [Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories], Vol. 4, p. 135.

- [2] Khanzadyan, Mariam. “Gndzik yev Ererin ghougheri (Bitlisi yev Vani vilayetner) korsvats sepagir ardzanagrutyunneri masin” [The Lost Cuneiform Inscriptions Once Erected in the Villages of Gndzik (Bitlis vilayet) and Ererin (Van vilayet)], in Ghahriyan Mushegh et al., eds. The Middle East (Parts XI-XII): History, Politics, Culture. Yerevan: Gitutioun, 2017.

- [3] Tatoyan, Robert. “Arevmtian Hayastani Bitlisi nahangi Sgherdi gavari hay bnakchutian tvakanake Hayoc ceghaspanutian nakhoriakin” [Armenian Population Numbers in the Prefecture of Sgherd of the Western Armenian Province of Bitlis on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide], Journal of Genocide Studies, No. 8 (1), 2020, p. 91․

- [4] Lapjinchian, Teotoros (Teodik). Koghkota Trqahye Hogevorakanoutyan yev ir Hotin Aghetali 1915 Tariin [The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915]. Tehran: S.N., 2014, p. 132.

- [5] Monahan, James Henry. Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh May and June 1898. London: The National Archives of the United Kingdom, open access at www.jelleverheij.net/sources/1891---1900/journey-in-sherwan/, pp. 157-158.

- [6] Ter-Sargsents, Aristakes (Tevkants). Aicelutioun i Hayastan, 1878 [A Journey to Armenia, 1878]. Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences, 1985, p. 115.

- [7] Maunsell, Francis Richard. “Central Kurdistan,” in The Geographical Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2 (1901), p. 141.

- [8] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, pp. 158v, 159.

- [9] Verheij, Jelle. “‘The year of the firman’: The 1895 Massacres in Hizan and Şirvan (Bitlis vilayet),” Études arméniennes contemporaines 10 (2018), pp. 133-134.

- [10] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, pp. 159-159v.

- [11] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, p. 200v.

- [12] Nor Keank, No. 6, May 13, 1898.

- [13] Kévorkian, Raymond, and Paul Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du genocide. Paris: ARHIS, 1992, p. 506.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Ter-Martirosian, Hovhannes (A-Do). Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzroumi Vilayetnere [The Provinces of Van, Bitlis and Erzurum]. Yerevan: Tparan Kultoura, 1912, p. 153.

- [16] Shiel, Justin. ‘Notes on a Journey from Tabríz, Through Kurdistán, via Vân, Bitlis, Se’ert and Erbíl, to Suleïmániyeh, in July and August, 1836,’ in Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 8 (1838), p. 78.

- [17] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, p. 169.

- [18] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy…, Vol. 3, p. 178.

- [19] Lehmann-Haupt, Carl Friedrich. Armenien Einst und Jetzt, Vol. 1: Vom Kaukasus zum Tigris und nach Tigranokerta, B. Behr’s Verlag, 1910, pp. v, 330.

- [20] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy…, Vol. 2, pp. 89, 320.

- [21] Vichakagrutioun Sgherdi yev ir Temeroun [The Statistics of Sgherd and its Dioceses]. Sgherd Prelacy of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, 1902 (Shirvan kaza chapter).

- [22] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, p. 159v.

- [23] Badalyan, Gegham. “Arevmtian Hayastani patmajoghovrdagrakan nkaragire Mets Yegherni nakhorein (mas VII-rd)” [A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide, Part VII: The South-eastern Counties of the Province of Bitlis], Vem, No. 4 (56), 2016, p. 24.

- [24] Ibid.

- [25] Verheij, The year of the firman…, p. 129.

- [26] Lynch, H.F.B. Armenia: Travels and Studies, Vol. 2: The Turkish Provinces (London, New York: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1901), p. 153.

- [27] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy…, Vol. 4, p. 135.

- [28] Cuinet, Vital. La Turquie d’Asie: géographie administrative, statistique, descriptive et raisonée de chaque province de l’Asie-Mineure, Vol. 2 (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1891), pp. 608-609.

- [29] Mayewski, Vladimir. Voenno-statisticheskoe opisanie Vanskogo i Bitlisskogo vilayetov [The Military Statistics of the Van and Bitlis Provinces]. Tiflis: Caucasus Military District Headquarters Press, 1904, pp. 155-156 (Annex section).

- [30] Tekin, Rahmi and Yaşar Baş, eds. Osmanlı atlası. XX. Yüzyıl Başları. İstanbul: Osmanlı Araştırmaları Vakfı araştırmaları, 2003, p. 81. [Modern edition of Mehmed Nasrullah, Mehmed Rüşdü, and Mehmed Eşref, Memâlik-i Mahrûse-i Şâhâneye Mahsûs Mükemmel ve Mufassâl Atlas, 1907].

- [31] Hayastanyayc yekeghecin Tachkastanoum [The Armenian Church in Turkey], Ararat, No. 2 (29), February 1896.

- [32] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, pp. 157-158.

- [33] Massis, February 5 (17), 1881.

- [34] Mayewski, The Military Statistics…, p. 26 (Strategic Study section).

- [35] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan…, p. 198.

- [36] Verheij, The year of the firman…, pp. 151-152.

- [37] Tekdal, Danyal. II. Abdülhamid döneminde Bitlis vilayeti (İdari ve sosyal yapı) [The Province of Bitlis in the Period of Abdul Hamid II (Administrative and Social Structure)] (PhD diss., Pamukkale Üniversitesi, 2018), p. 38.

- [38] Byurakn, No. 19-20, May 16, 1900.

- [39] Azatamart, No. 231, March 12, 1910.

- [40] Kévorkian & Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman…, p. 506․

- [40] Kévorkian & Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman…, p. 506․

- [41] Idem, p. 60.

- [42] Karpat, Kemal. Ottoman Population, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985, p. 174.

- [43] Tetik, Ahmet, ed. Arşiv belgeleriyle ermeni faaliyetleri, 1914-1918Cilt I (1914-1915) [Armenian Activities in the Archive Documents, 1914-1918], Vol. 1: 1914-1915. Ankara: Genelkurmay Basım Evi, 2005, pp. 151, 449.

- [44] Idem, p. 134.

- [45] Kévorkian, Raymond. The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 340.

- [46] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description…, pp. 24-25.

- [47] Virabyan, Amatuni, ed., Hayots ceghaspanutyune Osmanyan Turqiayum. Verapratsneri vkayutiounner [Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey: The Testimony of Survivors], Vol. 2: The Bitlis Province. Yerevan: Zangak-97, 2012.

- [48] Tevkants, Aicelutioun i Hayastan…, pp. 115, 126.

- [49] Ardzagank, No. 9, April 18, 1882.

- [50] Salname-i Vilayet-i Bitlis 1310 [Salnamé of the Vilayet of Bitlis, 1892]. Provincial Document Printing Office, 1308 (1890). The total of 15,729 is most likely a miscount, the sum total actually comes to 15,727.

- [51] Dadrian, Vahakn. “The Perversion by Turkish Sources of Russian General Mayewski’s Report on the Turko-Armenian Conflict.” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies No. 5 (1991), pp. 140, 150.

- [52] Mayewski, The Military Statistics…, p. 222 (Statistical Study section).

- [53] Sgherd Prelacy, The Statistics of Sgherd and its Dioceses, 1902 (Shirvan kaza chapter).

- [54] An independent See of the Armenian Apostolic Church that existed from the twelfth to late nineteenth centuries and was based in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross on the Aghtamar Island in Lake Van.

- [55] A-Do, Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzroumi Vilayetnere, p. 154, fn 1.

- [56] Teodik, Koghkota Trqahye Hogevorakanoutyan yev ir Hotin Aghetali 1915 Tariin, pp. 132, 764.

- [57] Non-Armenian readers should be aware that, in this study, the letter Ց ց appearing in Armenian village names and transliterated into C c, should be pronounced as a Z sound, as in the German word Zeitung, and not as an S sound or a K sound, as in the English words.

- [58] Sgherd Prelacy, The Statistics of Sgherd and its Dioceses, 1902 (Shirvan kaza chapter).

- [59] Virabyan, Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey… Doc. 76, pp. 117-118.