Mousa Ler – Festivals

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 14/03/15 (Last modified 14/03/15)- Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

Holidays and the rituals attached to them played a large role in the life of Mousa Ler Armenians. Often, they are linked to the church. While, on the surface, it is believed that Mousa Ler residents weren’t all that pious, deep down they were a people who followed convention and had faith. Holiday traditions always included church rituals and song that were respected by all. The traditional customs linked to the holidays (rituals, visitations and types of cuisine) were collectively preserved and celebrated by all. Of note is that holidays were called Zadag (Zadig). Pilgrimages and collective sacrifices to local holy sites were frequently made.

Gaghant (New Year)

The people of Mousa Ler called the last day of the year Gaghond. The very first to prepare for the holiday were the children. A week before the holiday they would cut a 4-5 meter of laurel branch and strip it until the end, leaving the tip bushy. On the morning of Gaghant, while dawn was just breaking, the singing children would gather at the church square where a large pile of wood was located. They would wait for an elderly baboug (grandfather) to approach, mutter a prayer wishing “keep the good, banish the bad”, and set the bonfire alight. The children would gather round the fire waiting for the signal allowing them to place their prepared laurel branches in the blaze. Once alight, the children would raise their branches in the air and then lower them again into the bonfire. The crackling of the burning leaves would fill the air. This ritual would last until the leaves were scorched to dust. Then, the crowd would break out into telling jokes, tongue teasers and witty banter. [1]

According to local lore, during the first years after Armenians accepted Christianity, a pagan king called Chour Ullianius (Evil Youlianos) sent the Armenian Catholicos of the day a bunch of green grass. The Armenian priests and princes sent the grass back to the king along with a nshkhar (consecrated wafer) emblazed with an image of the crucified Christ. Their message to the king was – “You are the grass eater, we eat bread.” Youlianos declares war on the Christian Armenians as punishment. By a miracle, the Armenians capture the king and win the lopsided battle. Heaping ridicule on him, they throw the captive king into a bonfire and pile on laurel branches and leaves as a sign of their so-called victory. The modern tradition of burning laurel branches might allude to this ancient fable. [2]

In the meantime, all the households start to prepare the holiday table – tsitu pigigh, banurhouts, zilibig, bourmou, aghounts…Dried fruits, nuts, vodka and wine are brought from the underground cellars. The boys bring the burnt laurel branches home and fashion canes from them. On the tips they will fasten bags to collect their New Year’s gift. This is probably the only holiday of the year when all the members of the family, regardless of age or sex) gather round a modest holiday table and make merry until the morning. At midnight, the sexton of the village church announces the New Year. Feasting and visitations continue until dusk. The boys go from house to house for djanta keril (throwing of gift bag). They’d knock on each door, shove the branch with the bag on the tip, and wait for it to be filled with dried fruit, nuts and sweets. Oftentimes, they would lower the bags down the chimney. Sometimes, witty household members would place burning embers in one of the bags as a naughty joke. The young people, in camouflage clothes, would enter houses cracking joke and just being foolish. The laughter elicited would be repaid in drink and food.

In the morning, all residents would go to church for the year’s first Divine Liturgy. For the entire day, kids would visit the homes of relatives and friends to receive their gifts. Naturally, they would first visit their godfather; the most respected of relatives throughout the villages of Mousa Ler. Waiting besides the door the children would say – Shinifir tsir gaghond. They would be welcomed inside, fed with delicious food, and then sent on their way. If someone was late when the boys visited, or didn’t satisfy their expectations, the visitors would utter the curse tsir heviren dzeoyu tgh gabva (May the hole of you chickens close). [3]

Another custom was for engaged young males to send their brides to be sort type of ornament, accompanied with a bunch of fruit. Another interesting tradition was that at night, when the guests had gone and the family was tired from all the feasting, for one of the elder of the household to tell fables to the rest of the family knelt around the fire. The fable would begin: Guginou, chginour, takavor muh guginou (there once was, and was not a king…).

Christmas and Blessing of the Water

People called this holiday Dounen Zedeg (dan zadig) or Bzdeg Zedeg; Little Zadig. On Christmas Eve, youngsters would walk the village streets, visiting each house along the way, while singing the glad tidings of Khorhourt Medz (O Great Mystery). People would show their appreciation by giving the singers presents. After completing their tour, the children would assemble in the churchyard to share their presents. If a spoon was given as a gift, it would be handed to the church for use at the hokedjash (memorial meal).

A widespread belief held that if a person makes a wish exactly at the moment on Christmas Eve when the trees bend, it will come true. In the wee hours of the morning, village youngsters would take the sexton’s bell down into the valley to swim in the creek no matter how cold the water. [4]

At the end of the Divine Liturgy, the Blessing of the Water (Chrorhnek) and Holy Baptism of Christ ceremony would take place. After filling the basin with water, the priest would immerse the cross in and declare an auction to be the godfather. Whoever pledged the most would become blessed godfather that year. When it came time to leave the church, the faithful would take some of the consecrated water from the baptism. [5] The priest and the sexton would then make the rounds officiating at the home blessing service. Village residents would pay short visits to one another, congratulating one another by saying Amun dara yas ouruh sagh ou parou tugh ginuk (may you be alive and well on this day every year).

Foods specially prepared for the holiday included klouruh madznuh shourbou, goulougasuh tutudjeor, bouranuh and herisa.

Saint Sarkis

St. Sarkis the Warrior is regarded as the prime saint for the Armenians of the region. In times of hardship they would seek his help by praying Ya Soup Sarkes, teon tugh hasnes (O St. Sarkis, come to my aid) [6] or Ya Soup Sarkes, purni zkoudes, chunni hikes…(O St. Sarkis, grasp my belt, let my spirit not leave…) [7]

According to tradition, St. Sarkis defeats and saves the Emperor of Constantinople. The emperor, amazed at his bravery, invites him to a feast during which the emperor decides to kill him. The young maiden who comes to kill St. Sarkis tells him of the emperor’s plan and confesses her love to him. St. Sarkis barely escapes and flees with the maiden to the caves of Mousa Ler. [8] Thus, there were three holy sites in the villages of Mousa Ler bearing the name of St. Sarkis. The first was the famous site in Kebusiye. There is a tributary, traversing the village’s north section, which leads to a gorge. There on a high cliff is a cave and in that cave a water basin with small holes resembling horse hooves. Local people had built a wooden ladder to reach the holy site. The second holy site was a cave on a slope emanating north of Yoghoun Olouk. The third sacred cave was located on the western side of Bitias. [9]

The custom was to prepare koumbou on St. Sarkis Day. Each family would cook this sweet bread to be used to tell one’s fortune. A metal coin would be placed inside the dough in addition to signs (a bean, chickpea, broad bean, a button, a bead, a fruit pit, etc.) symbolizing the family’s belongings. The dough was covered with the wide leaves of a plant called lvag and buried in the hot embers (maghmiugh) of an extinguished tonir until the morning to cook. People believed that St. Sarkis would wander through the villages that night and would leave hoof prints of his horse on the enchanted bread, thus blessing it. The next day, the koumbou would be brought to the table with much fanfare. Sliced in pieces, according to the number of family members, it would be shared amongst them. Each person would receive their piece of the koumbou. Naturally, the bread would not be flat where the various objects were hidden. Those spots looked like the trace left by a horse’s hoof. Underneath was hidden a person’s fortune according to the object in the piece of koumbou. These objects, could symbolize a wheat field, a vineyard, a garden, a milk cow, oxen, a flock of sheep, and even a rifle. Thus, depending on the object found in the koumbou, a person would manage or care for the specific family property symbolized.

The person who finds the doulout (lucky charm) in their piece is considered the fortunate one for the year. Surprisingly, however, family members would laugh out loud, advising the person to “throw it into the sea…” This is a reminder of the miracle when Jonah the Prophet feel into the sea and was saved, believing that the person was just as lucky as Jonah - they could be saved even after falling into the sea.

Visiting girls who are engaged was a must. In-laws would go see the brides to be carrying sweets, fruit, koumbou and gifts; especially if the girl had been fasting for three days for the St. Sarkis holiday. She would kiss the hand of her future mother-in-law and receive her gift; usually a silver coin. [10]

Vartanank (Vartan Saints Day)

It is commemorated each year on the Thursday prior to Poon Paregentan and the beginning of Lent. (Paregentan is also called the day of the harptsnoughoutsour/harpetsnoghats (intoxicated – because of all the eating and drinking).

That day is celebrated in churches by the Divine Liturgy and Repose of Souls services. The priest would give a fiery speech praising the Vartanants martyrs. Schools would be closed and no one went to work that day. In the streets, pupils would try to reenact the Battle of Avarayr but since no one wanted to play the role of a Persian soldier, the game never got off the ground. In the evening, families would gather around the table for feasting and the old folk would retell passages of the battle.

This day was also a time to visit engaged girls on the occasion of paregentan. In-laws, carrying sweets and gifts, would go visit the future brides.

1) A Mousa Ler family from the village of Kebousiye. Date of photo unknown. Most probably before 1915 or in the early 1920s (Source: Mousa Ler Compatriotic Union, Armenia)

2) A photo taken in Mousa Ler in the early 1930s. The man (wearing a hat) standing on the far right is Ghougas Mardirian. The woman standing immediately next to him is Djemileh Doumanian. The three boys (all wearing hats) seated atop the donkey are her sons; from left – André, Antoine and Maurice. The young girl sitting in front of them is their sister Antoinette (later Der Ghougassian) (Source: Mousa Ler Compatriotic Union, Armenia)

Paregentan (Convivial/Good Living)

Mousa Ler residents pronounced the holiday, which lasts two weeks, pergunduhng. The first week is relatively more relaxed, but the holiday is celebrated more lively fashion the second week. Everyone takes part in the festivities then. It is a much loved holiday, first because it is a period when no one works and people have time to make merry. The second reason is because every household must slaughter an animal, a ritual which adds to the festive spirit. The animal, specially kept for the occasion, is slaughtered early in the holiday and popular meat dishes are prepared – klour, herisa, trakh, khorovadz, etc., as well as banurhouts, siliug, ehdjdjuk, and the pastries zilipug, bourma, gatnuhouts, pigigh and pakhlava. [12]

On the first Friday, village youth select their leader, yegit bashi, in order to supervise the festivities. This person appears before the church council secretary, with some sort of gift (a bottle of vodka, a handkerchief, or 100 grams of tenbek [dried tobacco leaf]) seeking permission to publicly play davoul-zourna music, promising in advance to avert any unwanted incidents. Then, the person appears before the village mayor to get his permission. Having done so, the traditional music is heard in the public square and the paregentan holiday parade commences. The youth first dance around brandishing their gleaming swords, followed by the younger kids with their wooden swords and canes. Those who are late are penalized and must pay the musicians a fee. [13]

The festivities and group dances get livelier in the village square on Saturday. Oftentimes, these dances are a way for the youth to show off and attract attention. At all public events, including paregentan, there was a custom called dzkhiluh (burning incense to ward off evil spirits). An elderly woman would approach the dancers with a copper tray laden with a censer. She would twirl the censer around in a series of mysterious motions. The dancers, cupping their hands, would pull the vapors towards them, trying to breathe them in deeply. All the while the old woman would mutter – chiur achkuh tugh gournou, chiur nafasuh tugh chiunou (May the evil eye go blind, May the evil breath dry up). Naturally, the dancers would pay the woman for her performance.

Another Paregentan tradition that provoked laughter was imprisoning people. The yegit bashi (yiğitbaşı – group leader) would order that one of the boys be made to sit cross-legged on the ground in the middle of the dancers. A sword would then be placed opposite him. He would be considered “imprisoned” until he paid a ransom; either an animal for slaughter or a bottle of vodka.

On the first Sunday a game called dinirk uhneil (ascend the roof) was organized, Carpets (kilim) would be spread on the dirt roofs of animal pens and the soupra (table) would be spread. Despite the cold, a festive feast and merrymaking would commence. One of the common game played was the “king’s game”. Someone on the roof would be selected as king. The person would be dressed in gypsy clothes and be given a crown to wear. Another person would be elected “vizier” and all would obey that person’s commands. If someone was passing along the street, the king would order his policemen to go arrest the person. The hapless passerby would be judged before a “court” and accused on walking on the street without appearing before the king as expected and for coming empty-handed. A fine of a bottle of vodka would be imposed, and the person would be held until payment was made. If the prisoner balked, they’d be declared a cheapskate in front of the entire village… [14]

The dances usually start slow and heavy but really kick up steam at the end. Popular dances were: kiyabashi, dzoundur havou, and chalum dangi. The first two are group dances. The third is a duet danced with swords. Women had their special group dances and songs which they performed on the threshold floor; arm in arm.

Here are a few of them:

Leylamani (in the local dialect)

Aman ashgen tsir vetouanuh yeou gunnou.

Shoud mijgudver akakut mouroud gunnou.

Leyl amani amani, hey yamani yamani…

Gunni gourtou mandrasen

Pariuv gou dou Unturiasen.

Leyl amani, amani, hey yamani yamani…

Diunirk gunni gtndou,

Madga gourtou gkhndou.

Leyl amani amani, hey yamani yamani…

Antuh gachen kakminen,

Paklavinen,loukminen.

Leyl amani amani, hey yamai yamani...

Arvunen djaghur-djaghur,

Cheour tugh inna barvnen,

Leyl amani amani, hey yamani yamani…

Poutoukal kaghi lkiushiur,

Antseh knou shiud m’ishir,

Leyl amani amani, hey yamani yamani…

Antseh knou shiud m’ishir

At ashgayin ch’ishir.

Leyl amani amani, hey yamani yamani…[15]

Translation:

Oh, girl, wherever your fatherland is,

Don’t move about too much lest your dress gets dirty.

He/she gets up and goes from the square

Says hello to Antreas.

He/she goes up to the roof, it rumbles,

He/she dies, goes and laughs.

The brooks twisted and noisy,

Let the old people get sick.

Picks a large orange,

Go, leave, don’t look too long.

Go, leave, don’t look to long,

That girl isn’t looking your way.

Djouruhg Aghprgen (in the local dialect)

Hey djouruhg aghprgen,

Hangen bzdauh deyou undzi,

Hangen bzdauh sarehugi,

Dabgoudz heouvuh vareuhgi [16]

Translation:

Hey djouruhg [17] uncle’s wife,

Give me the smallest of the five,

The smallest of the five is a saryag [type of bird],

A fried chicken is a pullet.

Hey Truhnk, Hey Vazuhnk (in the local dialect)

Hey trayk, hey vazik,

Trayk inneyk kourvdag.

As ourtoghuh om ashgaynnuh,

At ourtoghuh Srpoug khanoum.

Hey trayk, hey vazik,

Trayk inneyk kourvda.

As ourtogh om horsniuh,

At ourtoghuh Mariam khanoum.

Hey trayk, hey vazik,

Trayk inneyk kourvdag.

As ougoghuh om asgaynnuh,

At ougogh Vartouheynuh [18]

Translation:

Hey, let’s fly and run,

Fly and fall, sisters.

Whose girl is she who goes?

The one going is Lady Srpoug.

Whose bride is she who goes?

The one going is Lady Mariam.

Rifle marksmanship was also a part of Paregentan Sunday. Boys would hang a chicken or a rooster as a target and then fire their rifles until the poor bird was killed. Those who weren’t able to kill the animal paid a fine. The one who did would take the bird as a prize. The money collected and the dead birds would be used to organize a feast that would bring the festivities to an end for the day. [19]

Another interesting tradition unique to Mousa Ler was to also organize a fire game called abdil. A sadj (puffy tray used for preparing thin bread) would be turned so that its concave side was facing up. Salt would be added and a fire lit underneath until it started to crackle. A cup of vodka would then be poured on top and lit. The mixture would give off red-blue flames. The faces of those around the flame would take on strange facades of yellow and green. [20]

Dyarnentarach (The Feast of the Presentation of Our Lord to the Temple)

Calling out Derendas, derin ee das, teenagers would roam the streets of the village collecting wood and brush to take to the church yard. After evening prayers, residents would carry candles and follow the priest’s procession, gathering around the mound of brushwood. New grooms would wait for the priest’s signal to light their brushwood with their candles. When the flames had died down a bit, the youth would jump over the fire in the belief that their dreams would come true. Residents would light their candles from the fire and hurry home to light their lamps. According to the belief, the Holy light brought from the church would keep snakes from entering people’s homes. From the burnt wicks of the candles people would manufacture a salve for the children. They’d rub the eyes of the children in order that they only saw good days, didn’t get sick, and to ward off evil. The church sexton would distribute special beeswax for that day. Small crosses would be fashioned and affixed to the door entrance and granaries as a talisman of bounty. [21] The remaining bits of half burnt wood from the bonfire would be scattered in the fields and under house fruit trees in the belief that the crop would be abundant. The old women would drip melted wax brought from the church on the hats of their grandchildren to ward off headaches. [22]

Medz Bahk (Great Lent)

This holiday was also called aghtsouts (aghouhats/salt and bread) in Mousa Ler. On the first day, all the pots and pans in the house were washed so that no trace of food was left. On the previous day, only children were allowed to eat paregentan meat and dairy dishes. Legumes (cracked wheat (dzedzadz), beans, broad beans and chickpeas) were always boiled and served. [23]

Michink (Mid-Lent)

This holiday was also called aghtsouts gis (half Lent) in Mousa Ler. In the morning, farmers would go to their fields to check on the sprouting crops. The special meal for the day was aghtsouts klour (Lent Ball), whose filling was made of legumes. Mother-in-laws would visit their future daughters-in-laws with gifts and trays full of grains. [24]

Dzaghgazart (Palm Sunday)

Also called Zarzartour. On the eve of the holiday, engaged boys would collect olive branches to take to the church the next morning. During the service, when the priest reads the passage regarding Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, the path adorned with psalm leaves, a commotion arises within the people. They attempt to cut the branches in order to bring some home. Girls would tie the boughs using their hair and boys would carry the branches by hand. Those leaves would stay in the house, in different corners of the house (in a flour sack, above the door, on the cattle shed or granary) until the following Dzaghgazart. People believed that the olives branches created abundance and warded off evil spirits. Branches would even be burnt and the smoke used as incense over the sick. [25]

Another tradition at Dzaghgazart was to collect wild flowers from the meadows and preserve them in a pail of water so that the water would be infused with their fragrance. People used this water called outnous (eight day), to wash their faces from Good Friday until Merelots.[26]

Avak Shapat (Holy Week preceding Easter)

All the days of the week preceding Easter are called Avak (Holy/Great). Those people not out working in the fields attend the daily special church services.

The Washing of the Feet service on Holy Thursday is of special note. Children, their feet cleaned, rush to church. Their moms would take oil from home to the church so that when the priest blesses the oil their household dairy items (also oil based) would be regarded blessed as well. After symbolically washing the children’s feet, the priest would make the sign of the cross with oil. The poor kids, wearing no socks, were forced to hop all the way home in order that the oil would remain. The faithful would take a bit of the consecrated oil home with them.

To share the tortures experienced by Jesus people would only eat garlic and onions, folded in unleavened thin bread, until evening on that day. At midnight, residents would flock to church for the Khavaroum (darkening) or All Night Vigil service.

The service begins with twelve candles lit on the altar. One of them is placed in the center and symbolizes Christ. There is also one standing out among other candles. It is black and stands for the betrayer Judah. When the seven passages are read from the Gospel (which reflect the prayer of Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, the betrayal of Judah, the commitment of Jesus to the crowd, His standing before Ann and Caiaphas, His being struck and mocked, Peter’s three denials and regret) teenage boys and girls would make bracelets with seven knots. As each of the seven passages is read, a new knot in the thread is fashioned in the bracelet that is later worn on the wrist while making a wish.

The washing of clothes or bathing is forbidden on these three days of mourning. On Friday evening Easter eggs are dyed red using onion skins to symbolize the blood shed by Christ. Dishes such as banurhouts and pigigh are prepared.

Medz Zadig (Easter)

People would attend Sunday morning Easter services at church. Even the children, holding their dyed eggs firmly in their pockets, waited impatiently to go. At the end of the Divine Liturgy, before kissing the cross, it was the tradition for the priest to utter a prayer and shake his liturgical vestments, thus blessing the sick standing near the altar. [27]

While the adults hurried to greet one another by saying Krisdos haryav I merelots and the reply, Orhnyal eh Harutiunuh Krisdosi, the youngsters were out in the yard doing battle with their eggs. The winner would take the eggs of all the losers.

Another tradition of note was that gunfire would be heard from all parts of the village as soon the Divine Liturgy was over. People called this Beokuh niditsen (Bahkuh zargin-they hit Lent). [28]

Families would gather around the holiday table where the main dish of the day was madznabour (madzoun soup with keofteh). Close friends would oftentimes call on each other to offer congratulations on the day. The priest would go from door to door performing the home blessing ceremony. The following day was Merelots, when people would visit the graves of family members and loved ones.

Hampartsoum (Ascension of the Lord)

There was no special service on this day. After church, those who so desired would simply picnic in the open while kids would go to the fields to collect flowers.

Vartavar (Transfiguration - Festival of Roses)

This holiday was called Vartivour in Mousa Ler. Under the burning summer sun, people welcomed this holiday. Some would go to a local spring and others would make a pilgrimage.

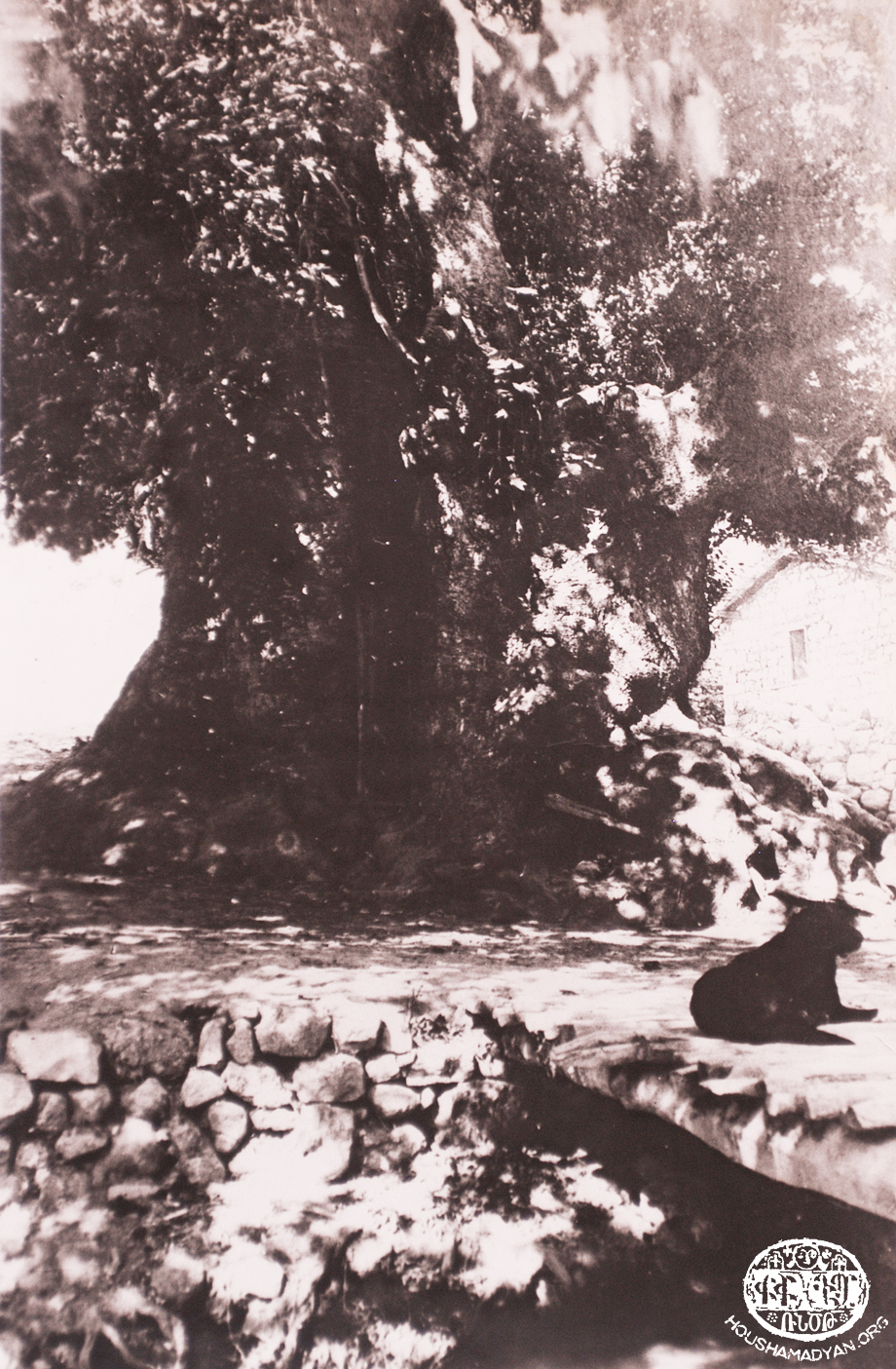

There was a large fountain in the middle of Kheder Beg surrounded by a number of cafes shaded by an ancient sycamore tree. The tree was so big that a table and a few chairs could fit inside a hole drilled in its trunk. After Divine Liturgy, people would go to sousutien (sosii daguh-under the sycamore). Dhol-zourna music, an inseparable part of all evens, would invite people to participate in the overall festivities. People would spread tables in the garden of friends where song, dance and merrymaking would commence. People would start by sprinkling water on each other. Afterwards, they’d take it one step further and start pushing each other in the fountain. There would be fireworks in the evening. Another tradition was to play the ‘watermelon’ game. You would have to hit a watermelon by throwing stones. Men sitting at the tables would play the arghoun (reed pipe), tamboura (tambourine) and violin. Teenage girls, and those a bit younger, in the shade of the laurel trees in the dale, would entertain themselves by making cradles from branches and by singing and dancing. [29]

Pilgrimages would start on Saturday. Families would climb to St. Mardiros Monastery to offer a sacrifice. They’d pass the entire night by singing and dancing while the sacrificial harisa and other delicious foods would slowly cook on the fire. The next morning, after the Divine Liturgy, the priest would bless the sacrificial meal at the entrance to the church. The pilgrims, in unison, would sit to eat. On the way back home, they would visit a small holy cave of the same name from where a spring flows. Pilgrims would drink from the spring, utter a prayer, and then tie colorful threads pulled from their clothes to nearby bushes. [30]

Khaghoghorhnek (Blessing of the Grapes)

This holiday was called Khaghoghuh Zadag in the local dialect. Starting on Saturday, villagers would take the best grapes in baskets to the church, believing that in this way their harvest and fields would be blessed. No one was permitted to eat grapes before the holiday. After the Divine Liturgy, the blessing of the grapes ceremony would commence, symbolizing blessing of the harvest and all things that grow. [31]

On the day, people would make a pilgrimage in honor of St. Hovhan Vosgeperan (St. John Chrysostom). Pilgrimages to the ruins of the saint’s monastery were organized starting Saturday. Lambs are sacrificed and preparations for the traditional harisa are made. Throughout the night, people gather in small groups around the table for merrymaking. Gunfire is an inseparable part of the festivities. The next morning an open air Divine Liturgy is celebrated and animals sacrificed. The festivities, accompanied by the strains of dhol-zourna music, continue. [32]

Sourp Khach (Holy Cross)

People called this holiday Khicheyn Zadag (Khachi Don) and would make a pilgrimage to the ruins of the Apostle Thomas (Tovmas) Monastery. In the days preceding the holiday, the church sexton would visit village homes collecting wheat for the harisa. In the meantime, donors would send a sacrificial animal to the church and children would roam the streets calling out Agh, tsiukh, pad…(agh, tsakh, payd-salt, twigs, wood) for the fire. The salt would be taken to the church for blessing. A portion would be fed to the animals for sacrifice. The rest would be used when cooking the harisa. The wood was taken to the monastery. Like preceding holidays, the harisa would cook overnight, accompanied by general merrymaking. That morning an open air church service would take place and the animal sacrifices blessed. The harisa was distributed to all and a portion left for those who for whatever reason stayed at home. [33]

Sourp Hagop (Saint James of Mdzpin)

According to local lore, after a long battle and siege, Patriarch St. James of Nisibis (Mdzpin) instructs his people to use the last remaining grains of wheat and roosters to prepare a final madagh meal to be eaten as brothers and sisters. While the people ate, the Catholicos open his arms to the heavens and prayed. Miraculously, the enemy lifted the siege and retreated. [34]

According to another local fable, the enemy surrounded the place where St. James was preaching. The saint instructs the people to arm themselves with shovels and sickles and climb o the roof. Seeing the resistance of the people, the enemy flees in fear. Meanwhile, St. James goes to the monastery. At that late hour there was nothing suitable to eat at the monastery. Al they had was a rooster, which they killed to make harisa to serve the saint. [35]

To commemorate that historic day, the people of Mous Ler would celebrate the holiday of Srpagip (Sourp Hagop) by using the last of the fall wheat for planting and rooster meat to make the harisa madagh. For this reason, the harisa cooked for that day was called khouruzuh hirisi (aklori harisa/rooster harisa). The holiday of Sourp Hagop was celebrated at the start of winter and the hills of Mousa Ler were often snow covered. Jokingly, people would tell each other: Sourp Egiupuh miurekuh uspudgtseouts (St. James has whitened his beard). If it snowed on the village that day, kids would have snowball fights and hunting aficionados would ascend the hills. [36]

[1] Mardiros Koushakdjian and Boghos Madourian, Memory Book of Mousa Ler [in Armenian], Beirut, 1970, p. 184.

[2] Tovmas Habeshian, Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh [in Armenian], Beirut, 1986, p.14.

[3] Krikor Gyozalian, Ethnography of Mousa Ler, [in Armenian], Yerevan, 2001, p. 244.

[4] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 174.

[5] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 48.

[6] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p 175.

[7] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 40.

[8] Ibid, p. 16.

[9] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 176.

[10] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 250.

[11] Ibid, p. 252.

[12] Ibid, p. 251.

[13] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 176.

[14] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 252.

[15] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 42.

[16] Ibid, p. 41.

[17] Djouruhg, handicapped.

[18] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 269.

[19] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 17.

[20] Ibid, p. 48.

[21] Ibid, p. 18.

[22] Hapet M. Iskenderian, Customs of Svediye [in Armenian], Cairo, 1917, p. 30.

[23] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 254.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid, p. 255.

[26] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 19.

[27] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 180.

[28] Customs of Svediye, p. 33.

[29] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 19.

[30] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 259.

[31] Ibid, p. 260.

[32] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 181.

[33] Ibid, p. 182.

[34] Ancient Echoes of Mousa-Dagh, p. 20.

[35] Ethnography of Mousa Ler, p. 262.

[36] Memory Book of Mousa Ler, p. 183.