Sassoun – Festivals and Beliefs

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 21/08/18 (Last modified 21/08/18) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The people of Sassoun were staunch traditionalists. Driven by a need to protect themselves from outside threats, they had settled in the peaks of the mountains, isolated and independent from other areas. Consequently, their lives were firmly anchored in customs, traditions, and beliefs that had taken root over the centuries at an exceedingly local level. The area’s geographic position and the resulting natural environment, with all their distinct manifestations, strengthened the local system of observations and rituals.

The people of Sassoun lived in large families, each independent of and insulated from the others. Consequently, they greatly looked forward to the holidays, which they marked with family-wide celebrations. They welcomed the holidays with joy and anticipation, seizing the opportunity to make merry, sing and dance, and visit one another.

Gakhendoghig (New Year’s Holiday)

The New Year’s festivities began with the ceremony of poshd-poshd, held on the final day of the passing year. People visited each other’s homes, joyfully bidding farewell to the previous year by chanting “Dere male, sere sale, khode kourek beka je malkhoye male!” (“The door of the house, the head of the year; may God grant our host a son!”). During these visits, people would inconspicuously put aside portions from the holiday dishes for the poor. Then all would go home to prepare for the coming celebrations.

On that night, youth would go from home to home, climb onto the roofs, hang their socks down the chimneystacks, and call out – “Gakhntogh togh-togh, her hip gaynem danki boloz, kamin toghouts zmer koloz!” (“New Year’s togh-togh (a type of bread); when I stand at the top of the roof, the gale blows away my hat!”). The residents of each house would fill the socks with holiday fare and see off the youth.

By then, the entire family would be gathered around the hearth. A large log would be placed on the fire, called the “Maryam log”, which would burn all night and keep the fire going until morning. By then, they would’ve taken the pot of cereal off the fire, and would be enjoying the boiled cereal. Then, the lady of the house would fill the lamp with fresh oil, insert a new wick into it, and light it. The family would bring out the best of its supplies from its pantries – fruits, dried fruits, raisins, nuts, and basdegh (fruit leather), all reserved for the holiday feast. The household’s children would play sedentary games, the family’s patriarch would tell fairy tales, and the women would be busy setting the holiday table. The embers of the burning log would be extinguished in the morning, and bits of it would be preserved, to be used during various occasions throughout the coming year. For example, during the preparation of the Maryamadjash on the fifth of January, some of these embers would be thrown into the fire, in the belief that this would grant plentiful milk and good health to the family’s sheep. On the following day, embers from the same fire would be baked into the darehats (New Year’s bread).

The most important dish of the New Year’s celebrations was the pournig, prepared in every household on the first day of the year. As a holiday kata (pastry), the pournig had be baked with wheat flour. While kneading the flour, the lady of the house would put aside one or two handfuls of it in a separate bowl, call over the family’s 8- to 10-year-old girl, and give it to her to knead. This flour would be left to settle, turning into sourdough, and this sourdough would be used to bake the darehats on the following day. As the first of the leavened bread eaten in the new year, the darehats was thought to bring blessings, prosperity, and wealth to the whole family. A small portion of this flour was also given to the family’s children, in the belief that it prevented stomachaches. Then, the remaining flour would be kneaded further by the lady of the house, in order to prepare the pournig. While waiting for the flour to finish fermenting, she would prepare the stuffing, using crushed walnuts, parched hemp, and sweet fruit basdegh. Once the hearth was hot enough, she would roll out the dough and fill it with the stuffing. She would also place two pieces of wood into the pastry, one for luck, and the other as a talisman of dovlat (devlat – prosperity or success). After sweeping the floor of the hearth, and with the help of the other women, the lady of the house would place the pournig in the hearth, and would then cover it with hot embers. The pournig would be ready in a few hours.

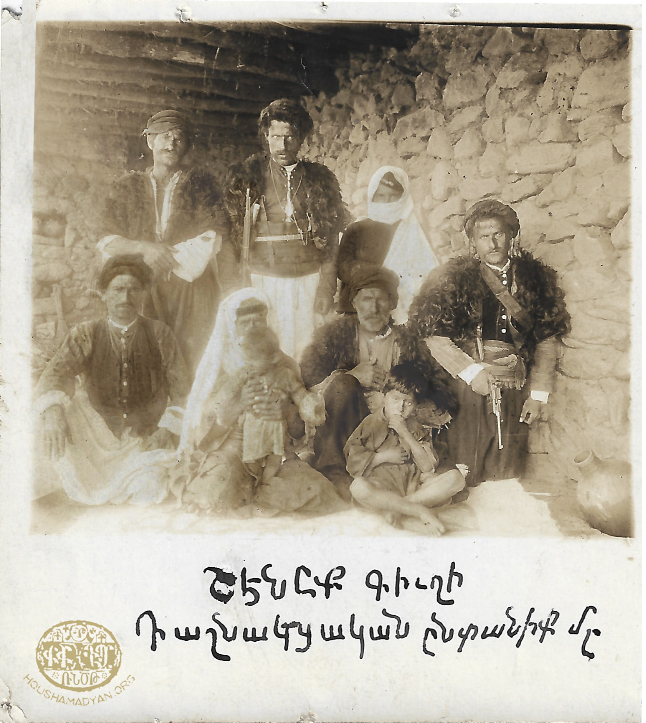

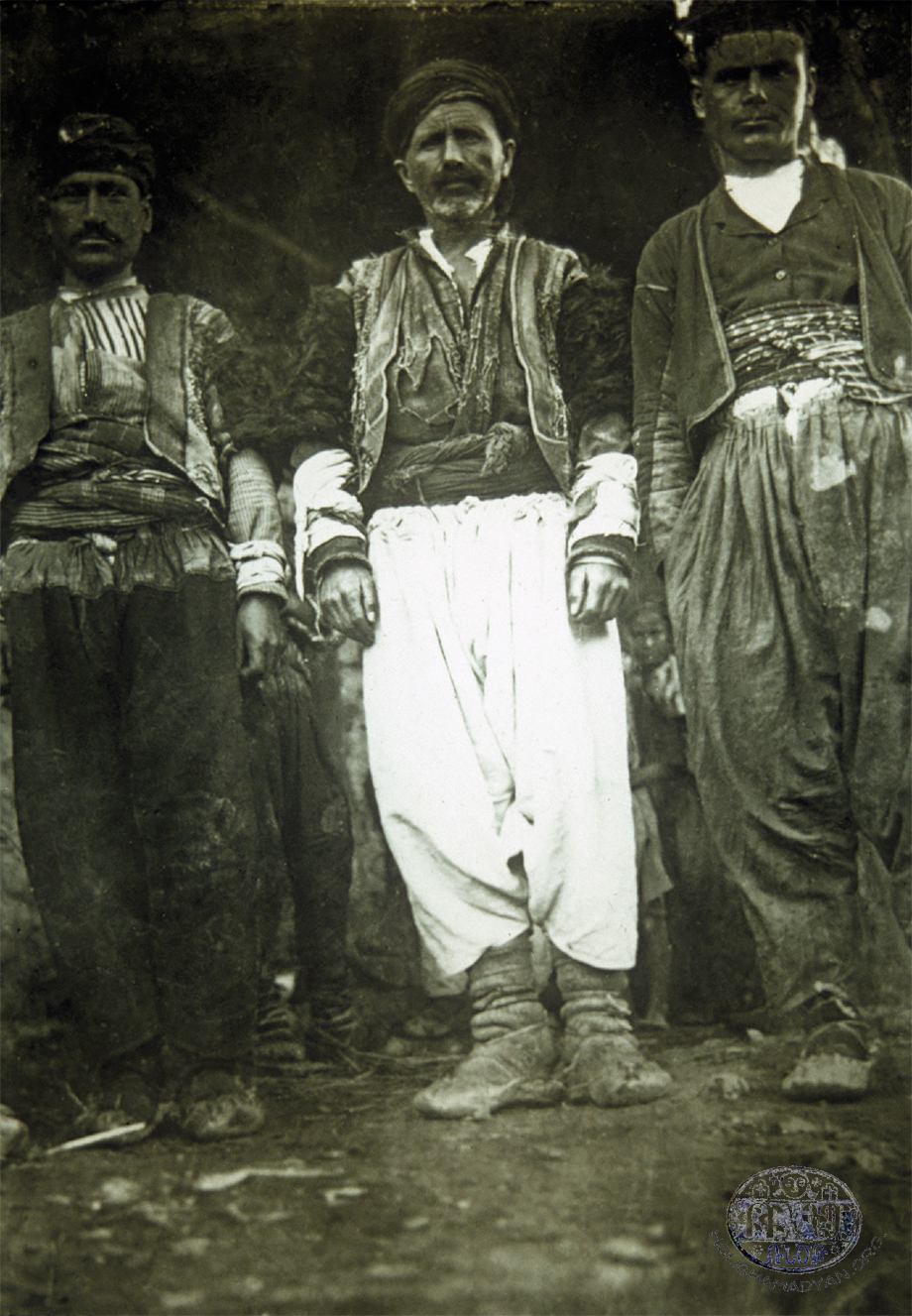

Residents of the Shenig Village of the Moush kaza (district), most probably photographed inside their home. The photograph was presumably taken between 1908 and late 1914. The inscription at the bottom of the photograph indicates that members of this family were members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Source: ARF Archives - Watertown, Massachusetts).

Before midnight, the pournig would be brought to the table. The embers would be brushed away from the top, and then the lady of the house would use the tip of a knife to separate the pastry into portions. In addition to a portion for each member of the family, slices would be earmarked for the household’s livestock, the birds in the sky, the local spring, etc. In some families, the pournig would first be placed before the family’s patriarch, who would recite the Lord’s Prayer over it, and then split it into four portions – one for the males in the family, the second for the females, the third for the animals, and the fourth for nature. They would then further split up the portions and enjoy them. A token would be hidden in the pournig, and whoever found it was believed to be endowed with luck for the coming year. It was also believed that another member of his or her sex would be born into the family. No water would be drunk on that night, believing that this would accustom the people to the parched days of the summer.

Christmas Eve

The special meal of the day was the Maryamadjash, a type of harissa prepared with cereals and greens. The pot would be left on a low fire while everyone rushed to church. After evening mass, they would return home holding candles. A portion of the meal would be set aside for the poor and those who had been bereaved in the preceding year. The sick, too, would receive meals from seven households, who would visit them and pray with them, beseeching God for healing. Children who suffered from warts would pick out chickpeas from the dish, of the same number as the warts they had, wrap them in a cloth, and stuff this cloth into a corner of the fireplace, believing that within 40 days, their warts would be healed.

Chrorhnek (Consecration of Holy Water)

At dawn, the lady of the house would knead and bake the special holiday kata, shaping it using the family’s unique pastry mold. According to tradition, each family had its own mold, which was never relinquished to another family.

Then, as dictated by tradition, the lady of the house would heat water, so that all members of the family could bathe. On this holiday, it was customary to slaughter animals as offerings. Every family would slaughter at least a goat or a sheep, with some of the meat earmarked for the poor. One of the hind legs and the hide of each slaughtered animal were the share of the local priest.

A cross would be left immersed in the water throughout the church ceremony. When the holy oil was dripped into the water, the people would carefully note the dispersal of the drops. The oil not dispersing readily was seen as a bad omen. If the water cleared up immediately, it meant the crops would be plentiful that year. Women would carry some of the consecrated water back home, children would anoint their faces with it, and then all members of the family would drink it and give it to their animals to drink, in the belief that the water prevented illness. They would also pour some of the water into the tub they used for storing flour, believing that this would bless their bread and all who partook of it.

Derndes (Derendes)

Youth would run around crying “Dern des, sabata ges, mer khout ou pout ges!” (“Derndes, halfway through February, halfway to our riches and prosperity!”). The men would pile twigs and leaves on a large roof and await the visit of the priest. After mass, the priest and the deacons would arrive, singing along the way. Afterwards, they would perform the rite of Antasdan (a religious rite in which the priest blessed all four corners of the world), and finally, the priest would give his blessing – “May God bless our people; he who gives a lamb will be the first to light the flame.” And thus, whoever offered a lamb for slaughter won the right to light the fire.

The women, who until then had waited, standing in a row under the wall and holding oil lamps, would approach to light their lamps from this bonfire, and would then carry these lamps home, alongside the light and warmth of the blessed fire. This lamp had to stay lit until the following day. The men would sear leafy branches on the fire until the branches blackened. They would then take these branches home and rub them on their cattle. The shepherds would do the same. Then, when the flames receded, they would take the embers and scatter them in their fields, in the belief that this would bless the soil and bring prosperity. Young girls would throw a specimen of their embroidery into these flames, entreating God for even greater talent and the ability to learn more intricate patterns. The elderly would pour some of the ashes on snowballs and swallow them, in the belief that this would prevent the kami (an illness that struck the elderly in particular, causing intense shivering in the cold season). Women would mix the ashes with salt and feed it to their animals, while others would hold a bale of grass over the fire and feed that grass to their sheep on that same day. Recent mothers would walk around the fire seven times while holding their newborns. The young men would jostle each other into the flames, then jump over them. It was also customary to organize games in which they competed.

The shepherds would light Derndes fires outside their shacks in the mountains. In villages that lacked priests, it was customary to light several fires at several locations. At night, the sight of flames shooting up from various parts of these villages was a spectacular scene.

Kchkoni or Kamadeghik

On the Thursday of the Vartanants week, women would prepare the day’s special dish, made with dry milk curds. The entire family would gather around the hearth and partake of the meal. Then they would hang a rope from the ceiling, and take turns sitting underneath the swaying rope and exchanging good wishes – “Kamdeghig, deghig, deghig, im mamou pchouchig elli yeghig, im babou ksegig elli badig!” (“Kamadeghig (or kamateghig, the custom of swaying to be healed from illness), may my mother’s pots always be filled with oil, may my father’s pocket always be full!”). Meanwhile, the older members of the family would whisper their prayers and blessings – “God, give good fortune to my daughter. Bestow the crown of betrothal upon my son. Grant us a good death and deny us not thy kingdom.”

Feast Day of Saint Sarkis

Prior to the Feast Day of Saint Sarkis, the people of Sassoun – from the age of six to the elderly – would faithfully fast, eating only one meal per day, in the evenings. There were also those who took their fervor to another level, and had only one meal in the four-day period preceding the holiday.

In order to accustom children to fasting, the adults would call them “lousik bahogh” (“keepers of the light”), and would convince them that if they fasted, God would be sure to protect them into old age. On the morning of that Friday, mothers would bake a special type of flatbread for the children, in addition to the salty shourhats (or shour gougou), another type of flatbread, prepared for youth who had reached the age of marriage. That night, these youth would eat the salty flatbread and go to bed without quenching their thirst. They believed that whoever gave them water in their dreams would become their future spouse.

On that day, it was incumbent on all to wear their best clothes. They would gather and spend their time chatting, playing, and singing. This was meant to distract them from their hunger. Throughout the day, they would beseech the saint – “Saint Sarkis, tighten my belt, don’t let my spirit escape.”

The women would roast cracked wheat (dzedzadz) and corn, and then grind the roasted grains. The cereal would be used on the following day, to prepare the holiday’s special dish, pokhende djash (khashil). The mothers, anxious about their famished children, would be unable to sleep that night, and would rise early in the following morning to prepare pokhints pudding, djadjaroun with flour, or bread soup for the children to eat as soon as they woke up.

The pokhende djash was prepared in a large pot. All members of the family would gather around the table and partake together. Youth would secretly place a small amount of the food on the roof, and wait for a bird to eat it. It was believed that fortune would come from whichever direction the bird flew afterwards.

Shevtahan

Shevot/shevod (sabat or pourdig) was the name given to the spirit of the winter. It was a corruption of the word Pedrvar (February). At midnight, on the first day of March, all members of each family would pick up sticks and strike the walls, corners, and floors of the home, thereby scaring away and expelling the spirit of the winter from the home and inviting in the spring. While performing this ceremony, they would chant “Out with you, February! Come in, March!”

The people of Sassoun gave the name of zib to the week-long period stretching from the end of February into early March, during which the weather was very unpredictable. This weeklong period was also known as baravi kami (“hag’s gale”) or baravi ouler (“hag’s kids”).

A small copper cross bearing the inscription “Liberty to Armenians – Constitution 1908.” The inscription also includes the name “Dikran Garabedian, Senior Deacon” – presumably the owner. It is believed that this cross was hidden for long years by Islamized Armenians living near the Arakelots Monastery in the Moush Valley. Around 1975, when French art historian Jean-Michel Thierry visited the area, he was approached by local villagers who traced crosses in the dirt to reveal their hidden identities to him. Later, they entrusted the French art historian with their priceless copper cross. Upon his return to Paris, Thierry gifted the cross to Armenouhi Kevonian (nee Der Garabedian). She was a native of Moush and had visited the Saint Arakelots Monastery. This artifact is now preserved as part of the Kevonian family’s collection in Paris.

Barkandan (Paregentan) (Shrovetide)

The most festive holiday in Sassoun, as it was throughout Armenia. Women would prepare a variety of dishes, and the people would feast on their roofs, singing, dancing, playing games, and challenging each other in competitions. They would visit each other, exchange good wishes, and generally make merry. All the people of Sassoun, whether male or female, old or young, earnestly participated in the festivities, despite the cold weather.

Mgan Monday (Clean Monday)

This was the name given to the first Monday of Lent. People would go up to their roofs, rub two rocks together as a signal, and call out to each other –

- “Agham, agham, zinch agham?” (“Grind, grind, what should I grind?”)

- “Agham zmgner, zgaridjner, zotser.” (“I will grind mice, scorpions, snakes.”)

- “Agham, agham, zinch agham?” (“Grind, grind, what should I grind?”)

- “Agham zchar lezoun, zchar achkn yev zchar tevn.” (“I will grind the evil tongue, evil eye, and evil spirit.”)

- “Agham, agham, zinch agham?” (“Grind, grind, what should I grind?”)

- “Agham zmer doushmanner, zkurder, zturker.” (“I will grind our enemies, the Kurds, the Turks.”)

- “Agham, agham, zinch agham?” (“Grind, grind, what should I grind?”)

And thus, they would grind away with the rocks while conceiving additional lines, in the belief that by spending the day in repentance and in the performance of this ritual, just as by depriving themselves of food and pleasure, they could ward off the calamities mentioned in their ditties.

The ceremony of washing the dishes on this particular day was called farakh shoy. Women would wash all crockery in the house, in order to erase any trace of non-Lenten days. They would then clean the home’s ceiling, floor, and chimneys. They would rub limestone powder onto the ceiling beams. Afterwards, they would always assemble the frik, a sort of Lenten calendar, consisting of seven feathers thrust into a large onion. This contraption would be hung from the ceiling, in order to remind the children not to violate the rules of Lent. Every Saturday, women would remove one of the feathers and throw it into the flames of the hearth.

Pilgi Sunday (Bright Sunday)

Winters were very harsh, even brutal, in Sassoun. In late autumn, when the first strong claps of thunder were heard, the people would lean against a wall and stand still and tall, believing that this would endow them with additional strength. This first Sunday of Lent would be marked with ceremonies celebrating the forces of nature, especially thunder and lightning, hoping that these powers would not lay waste to the people and their belongings in the months until the arrival of spring.

Gadghashan or Almighty Sunday

A special ceremony was held on this day to prevent hunched backs (spinal deformities) and rabies as a result of dog bites (both conditions were common among the locals). The ceremony was unique, and its function was to ward off these conditions.

Houlou Kul or Horekil

Halfway through Lent, on mid-lent Wednesday (michink), women would get together and bake the michink bread. A special token would be baked in the dough, and whoever found the token was deemed to be blessed with fortune.

Storm Sunday

One of the Sundays of Lent was dedicated to the powers of snow and blizzards. The people would pray and make offerings to God, beseeching him to protect them from these winter-time calamities. Each year, many people in Sassoun died as a result of fierce snowstorms. During these storms, the maraz would dislodge chunks of frozen mountainside and toss them to and fro, while the hshgi (housi) would drive the snow relentlessly and block the roads, sometimes forming impassable hills of snow. Occasionally, during these storms, cries of “Hay! Hay! Havar e!” would be heard, followed by men running to the roads with large wooden oars, in order to rescue people who had been stuck under these piles of snow.

Zarzartig (Palm Sunday)

At midnight, the pealing of bells would invite people to church. They would head to church carrying their mompats (long and thin candlesticks), to attend the ceremony of lighting of the candles. They would all light their candles simultaneously, illuminating the church vault. They would also light smaller candles on the walls, in memory of their deceased loved ones. Once the candles melted down to the size of a finger, people would roll them into rings and hang them from their necks, believing that this would protect them from snake bites in the summer.

A bushel of willow branches would be placed in front of the font, and candles would be burning on these branches, too. After the readings from the Bible, the priest would strike the bushel, breaking the branches into pieces. The congregation would then join the priest, and each would pick out a branch, which he or she would fashion into a ring and wear on a finger while beseeching God to keep them safe from the painful condition known as kobnod, which caused irritation of and bleeding from the fleshy parts of the fingers.

In the morning, youth would pick out the straightest willow branches, wilt away the rind covering them, then wrap the branches back in the rind and smoke the branches over a fire. Afterwards, when they removed the rind once again, sections of the branch would be blackened, and they would carve sigils into these sections. These small staves were called khatabriks or khitapediks. This was a day of joy for the youth. Waving their khatabriks, they would go from neighborhood to neighborhood, house to house, crying “Khitapedik, zarzatig…” Women who heard them would come out into the street and offer then eggs from their chickens, to be used in the upcoming Easter celebrations.

“Red” Easter

Almost all the people would fast on Saturday, and in the evening head to church on foot, to participate in the Holy Saturday mass and receive communion, which the locals called bardzrarik. People would then return home and immediately gather around the festive table. They would break their fasts by eating the first painted eggs of the holiday, after which they would partake in a regular fare of yogurt, cheese, etc. The act of breaking one’s fast was called khetil by the locals.

The people of Sassoun had a unique egg tapping tradition. Broken eggs would be rolled like marbles, and whoever successfully rolled his or her broken egg into another’s won both.

On the following day, animals offered by the people would collectively be slaughtered and cooked, and the meat would be distributed to all.

April 7 – Basembol

On this day, girls, brides, and young women would gather on the roofs, and weave patterns called basembols using red and green threads. They would then adorn these patterns with colorful ribbons and beads. Adult women and the elderly would weave these basembols into scarves. According to custom, they would then take these scarves to church to be blessed during mass. They would tie these scarves around the necks and horns of their cattle as amulets. They would also stitch talismans made of the wax of Palm Sunday candles into these scarves, then gift them to their children or loved ones.

Hampartsoum (Feast of Ascension)

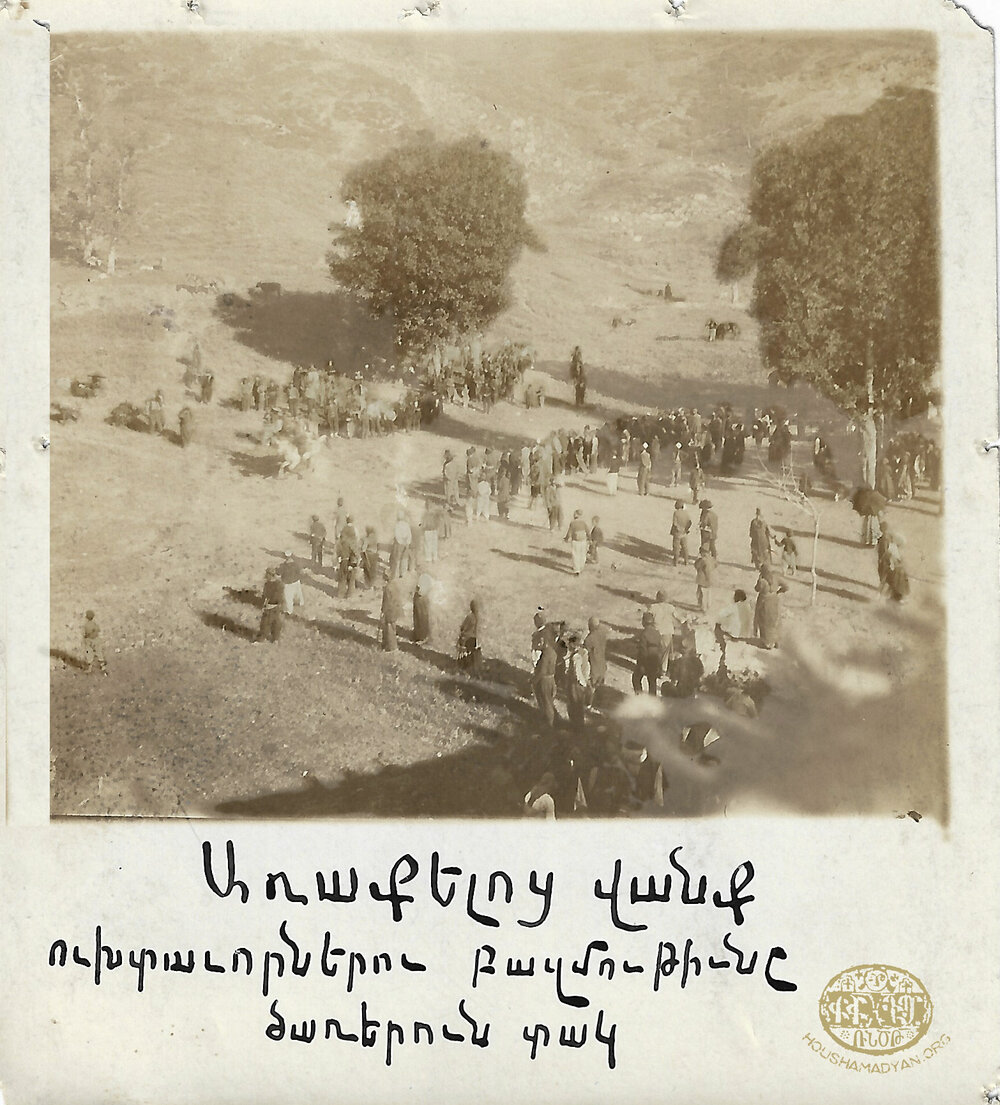

On this holiday, entire families would make lengthy preparations to go on pilgrimage to the Saint Atanakine (or Saint Antania) Monastery in the mountain forests. Customarily, each household would bring a sheep or a goat as an offering. All would be dressed in their best holiday attire, with the women and girls adorned with the best of their ornaments, and the young men carrying daggers and rifles. Before setting out, they would pray – “Ov Sourp Antania, aha zmer bede kezi gdank. Tou zmer mouradn idas” (“O Saint Antania, we give you what is ours, grant us our desires”). They would make the journey in groups, and were often joined by other families along the way. Sometimes, the men would climb the hills and fire their rifles into the air, thus keeping each other informed of their progress. The girls would sing and make wreaths of flowers to wear on their heads or around their waists.

Upon entering the forest, all would cross themselves and whisper – “I declare my faith in and confess to thy holy visage.” Men would fire their rifles, and the sound of the dhol and zourna would fill the air, while the newly arrived groups settled down. Each family would build a fireplace to roast the meat of whichever animal it had brought. The young men and teens would already be absorbed in their games and competitions. The young women would either watch these games or participate in songs and dances. The favorite dances of the people of Sassoun were the Mardlotsoug and Yarkhushta. The festivities would also feature acrobats, and the young men would show off their bravery and ingenuity in marksmanship contests. This was also an opportunity for them to show off to the young women. There was a high likelihood of young men and women falling in love during these festivities, and according to tradition, couples who met (or became betrothed) on this day were blessed with fortune.

Within this forest was also a sacred spring of holy water. According to popular belief, the waters would dry up if an unworthy person bathed in them. The sick were thought to be cured by bathing in these waters, and the healthy were thought to gain protection from various diseases and other perils.

The festivities would last all night, and the meat of the sacrificed animals would roast over the fires. The melody of flutes would rise from some of the groups. After morning mass, each family would gather around its own table, and before partaking in the food, it would put aside a share for the clergymen and for the poor.

According to legend, on the eve of the holiday, two stars in love with each other, Leyli and Mechnoun, met in the firmament and kissed. The moment of their meeting infused the world with magic, and whoever witnessed this moment and filled a pail with water at that very moment would find that the water had transformed into gold.

Vartavar

On the occasion of Vartavar, each village would organize an expedition to its holy site. Once again, animals would be slaughtered as offerings, and the people would celebrate with song, dance, and popular games. It was customary to weave crosses of strawflowers and offer them to God, hanging them from the walls of the church. Around the springs, people would drench each other with water, beseeching the water’s blessings for the year’s crops. A related ritual was the washing of khachkars with water during times of drought.

A large, four-day pilgrimage expedition would be organized to Mount Maratoug. On the first day, the pilgrims would scale the major peak of Maratoug, and on the second day, the minor peak. The final two days of the expedition were dedicated to festivities. Animals were slaughtered; pigeons were flown; people drenched each other with water; and engaged in wresting, song and dance, marksmanship competitions, horseracing, games, etc.

Other Traditions and Beliefs

The worship of heavenly bodies and the elements of nature held an importance place in the culture of Sassoun. Mount Sim, in Sassoun, was considered to be the seat of lunar divinity. The mountain was also home to the Saint Antania Monastery, beloved by the locals. During lunar eclipses, men would fire their rifles at the moon, in the belief that by doing so, they were helping the benevolent gods in their battle against the evil ones.

On moonlit nights, mothers would go up to the roofs holding their newborns. The newborns would be made to face the moon, and soot would be rubbed on their faces and hands to protect them from illness. Older children would have copper coins hanging from their necks, cut into the shape of the moon. Lunar eclipses were considered very bad omens. Men would climb to their roofs and shoot at the moon, while women prayed for the end of the eclipse and pledged offerings to God.

The same actions were taken during solar eclipses, which were through to augur impending bloodshed and war. The worship of the sun had deep roots among the people, and the practice of swearing by the sun was widespread. When baking bread or pastries, the rays of the sun were carved into the dough.

The people believed that the number of stars in the sky corresponded to the number of living humans. Each person had his or her own star in the sky. The number of stars increased with each birth and decreased with each death.

Their word for a rainbow was agheghnoug. When they saw a rainbow, they went to the spring and drew water, believing that this would ensure a plentiful supply of oil for their families. When one end of the rainbow was in the water, it was a sign that rainfall would continue. If a person ever walked under a rainbow, his or her sex would change.

Silent thunder meant that snowfall was coming. If thunder was clearly audible, it meant rainfall was coming. If thunder was uncommonly powerful, it meant hail was coming.

Lightning only struck the evil, or those who had been infected by evil. Hence, during a lightning storm, the people would not stand in their doorways, as they believed that evil lurked in doorways. They would continuously repeat the name of Christ to ward off evil and protect themselves against the lightning bolts.

Land was sacred for the people of Sassoun. They swore by the land – “Heyte hoghe tegh veka eghni” (“May this soil bear witness”). Some of the customs that had survived since times when the land was worshipped was the act of kissing the soil or genuflecting, as well as the act of rubbing one’s face against the soil. During funerals, loved ones bid farewell to the deceased by pouring handfuls of soil onto the coffin. Those who emigrated took with them a handful of soil from their native land. The land surrounding monasteries could not be sold, and was considered hallowed. Moreover, hunting was prohibited in the vicinity of holy sites. When entering holy sites, men would leave their rifles behind.

The holiday of Derentes was a telling example of ancestral worship of fire. One of the vestiges of pagan fire-worship was the act of swearing by a hearth – “May the hearth of your home bear witness!”, as well as curses related to it – “May your hearth be extinguished!” One of the duties of Sassoun women was to always keep the hearth fire lit. At night, they extinguished the flames in such a way that it was easy to rekindle them in the morning.

The epic poem Sassountsi Tavit (Tavit of Sassoun; Daredevils of Sassoun) clearly demonstrates the ancestral practice of water worship in Sassoun. Dzovinar is impregnated with Sanasar and Baghdasar after drinking two handfuls of water from her native spring. When Sanasar drinks the miraculous water of the spring, he says – “Aznants vortou chour e, ov vor etor agan chour khme, etbes gdridj gelni” (“It is the water of the sons of braves; whoever drinks the waters of this spring, will be brave as the braves”). Kourgig Djalali (Tavit’s steed) was born of the spring erupting from Mount Andok. Before the decisive battle, Taghtsoun Dadig dispatches Tavit to drink the water of “Mher’s gatnaghpur (spring of milk)”. Kourgig Djalali brings Tavit to this spring, then “kneels before” it.

There were many springs, streams, and brooks in the mountains of Sassoun. They were known by curious names. For example – lousaghpur (spring of light), gataghpur (spring of milk), otsaghpur (spring of the snake). The people of Sassoun believed in the medicinal and curative properties of these waters.

The worship of water was closely intertwined with the worship of dragons, which were symbols of lore and immortality. The Houshp (Dragon) road was a mountain pass that the locals approached with reverence. The region of Sassoun was home to the ruins of the ancient settlement of Vishab (Dragon). One of the vestiges of dragon worship was the worship of snakes. The people of Sassoun considered snakes to be faithful protectors of their homes, and consequently allowed them to freely roam inside their homes. Images of dragons and snakes were often knitted on children’s hats, believing that the children would grow up to be dragon-blessed. Men would stitch pieces of snakeskin into their clothing, and some would even keep entire molten snake dermises in their pockets, believing that this endowed them with strength.

According to Sassoun legend, when snakes aged, they made their way to the springs of the Dzovasar and Gepin mountains, to quench their thirst. Then, after eating the flowers of eternity growing at the sites of these springs, they slithered into the waters, shed their skins while swimming, and came out of water reborn and rejuvenated.

There was a miraculous spring near the Saint Antania Monastery, which the Kurds called Ganie Maran (Otsaghpur). According to local legend, a giant, wounded snake once crawled into the waters to swim. A few minutes later, it came out of the water completely healed, shook off its old skin, and transformed into a shahmar (snake king) before slithering back into the forest. A chapel was built above the spring, in which the spring’s waters formed a pond. The sick bathed in this pond seeking cures to their conditions, then lit candles, burned incense, prayed, and returned home carrying some of the holy water with them.

There was a moon-shaped lake at the summit of Mount Dzovasar, which was named after the Holy Virgin. The otsaghpur on the flanks of Mount Gepin was called Garmir Djagad (Red Forehead).

Mount Andok was the highest peak in Sassoun. At its feet, in the town of Merger, was the spring known as Baytogh Aghpur (Erupting Spring). According to legend, there was a sea inside of Mount Andok, as well as flaming horses, who galloped out of the spring to visit the earth and lay eyes on the sun, but immediately plunged back into the mountain’s depths when they sensed the presence of humans.

Mount Maratoug was the most beloved of the mountains in Sassoun. The area around it encompassed the most popular of the region’s pilgrimage sites. In The Daredevils of Sassoun, on the eve of the decisive battle, Lion Mher and Tavit go to pilgrimage to Maroutavank (Maratoug Monastery). Reverence for the mountain had been passed down from generation to generation, becoming more and more embellished along the way. The people told of how Mount Andok, the king of mountains, had once become envious of Mount Maratoug for being such an object of worship, and had challenged it to battle. During this battle, Andok struck Maratoug with its sword of lightning, causing a large gash on Maratoug’s head, cleaving its summit. For this reason, people sometimes called the mountain choughdag klough Maratoug (Maratoug of the twin heads). In response to Andok’s strike, Maratoug lifted up a large boulder and tossed it at Andok, hitting him in the chest and wounding him. The people believed that the tati kharan (pawprint) of Maratoug was the result of this wound. It was located at the meeting point of Mount Andok and Mount Gepin.

There was another legend associated with the stones known as Sharakars, standing on the flank of Mount Maratoug. They were believed to be a shepherd and his flock that had turned to stone. According to the legend, the shepherd went up the mountain on a hot day in summer, alongside his flock. Suffering greatly from thirst, he climbed up a small hill, and played a touching melody on his flute, moving the mountain and the valleys to pity. He begged for water from Maratoug, and pledged to offer one of his flock’s sheep as a sacrifice in exchange. An icy spring soon erupted from among the rocks, quenching the shepherd’s and the flock’s thirst. However, once satisfied, the shepherd reneged on his promise. Maratoug, enraged, turned him, his flock, and the spring into stone.

At another location on the flanks of Mount Maratoug was a rock that the locals believed was stamped with Sassountsi Tavit’s fingerprint. According to legend, when working as a shepherd and escorting the herds, Tavit saw a rock rolling down the mountain towards the cattle. He leaped into action and stopped the rolling rock with his own hands, leaving his fingerprint on it in the process.

The people of Sassoun believed in the “evil eye,” which haunted attractive men and women, good marksmen and riders, successful merchants, remarkable animals, and all who stood out among the rest. Consequently, people and animals who attracted attention were hidden away as much as possible from the public. Mothers sewed amulets, coins, and colorful fringes onto their children’s clothing as protection. They would fill a cup with pins and pour coffee into it, then have newborns drink that coffee, to ward off the evil eye. They would also pierce the newborn’s pillow with pins. However, if the evil eye had already struck its victim, the people would appeal to devout women, who would pray over salt, bread, or boiled eggs, which would then be fed to the victim. There were also women who “read cards,” and who prepared various antidotes for those who had been “stricken.”

The hair of male newborns was not combed, so that his teeth would grow strong. They would only cut his hair after he teethed. If only one son was born into a family, especially if his birth was fraught with danger or difficulties, the parents would vow not to cut his hair for seven years. At the age of seven, the parents would take the boy on a pilgrimage and shave his head, and then distribute the hair’s weight of silver to the poor.

When a child lost his or her first tooth, the tooth was placed under the chimney, and while opening and closing the door, the family would chant – “Mantr-mantr gats karan, khayim-khayim gats choroun” (“Let the teeth be small as a lamb’s and strong as a mule’s”).

The first of the oil pressed by a family in the spring was donated to the church. Around this time, a mass on the occasion of Djrakalouys would be held, celebrating the spirits of the mountains and beseeching them for plenty of milk from their cattle. The first batch of flour obtained from each year’s cereal harvest would be baked into bread and donated in its entirety, as thanksgiving for the year’s crop.

The people of Sassoun would visit holy sites to treat certain illnesses. There, they would perform various unique rituals. In cases of frost bites and shivers, they would collect rocks from holy sites, heat them, and then rub them on the body. They would also rub mud on the shoulders, the feet, and the arms. A piece of clothing would be torn and tied to the branches of a tree growing at a holy site, believing that the pain or illness would be left behind in the cloth.

In cases of snake bites, they treated victims with colorful beads called teghtaps, which they collected from the fields. According to the local grannies, these beads “fell from the sky like hail.” When killing a snake, one had to utter the phrase “Zkou amanat chgortsous!” (“May you not lose what you have!”). The people of Sassoun also gave the name of amanat to the black gallbladders of snakes, which they used as medication for the eyes.

In cases of scorpion stings, the victim was taken to a height from which the summit of Mount Maratoug was visible, in the belief that concentrating the vision for an extended period on the summit of this sacred mountain would neutralize the venom. According to popular legend, an ascetic named Marout had lived on the mountain, who was considered the holiest man of his time. He had died of a scorpion’s sting, and his grave was at the summit of the mountain. A monastery had been built atop his remains, named Maroutavank. Later, the mountain had taken its name from this monastery.

The deep valley to the west of Mount Maratoug was called Dabanag [Little Ark]. It was said that when Noah’s ark had floated through the area, one of its wooden logs had fallen in this valley, from which it had taken its name.

Every year, in the summer, terrible explosions were heard from the direction of Mount Maratoug. The locals gave this phenomenon the name of “Maratoug’s cannon.” They explained that the mountain fired off its cannon to keep evil people away from it. When women cursed, they said “Maratgou top arne ko chan!” (“May the cannonball of Maratoug strike you!”) or “Maratgou top zkou doun kante!” (“May the cannonball of Maratoug destroy your home!”).

A series of unique beliefs and superstitions had developed in Sassoun over the centuries in relation to the characters and significance of certain animals.

If a dog gazed at a house mournfully, or if it whined in a monotone fashion at a house, it was believed that the house would soon be stricken by tragedy or death. But if a dog whined in such a manner while staring up at the moon, it augured a widespread calamity. The people believed that the spirit who strangled infants was kept at bay by dogs. Consequently, if newborns died in infancy in a family, the parents would give the next child the name of a dog. Some even believed that dogs could heal wounds by licking them.

Cats were considered to be Christ’s tasdmalns (“purifiers”). Therefore, to kill a cat was a major sin, which could only be absolved if the sinner slaughtered an animal right outside the church. People were afraid of following cats at night, believing that cats led people to their graves, where they would transform into skeletons and strangle their unwary victims. If a cat wet its paw and cleaned its face with it, it meant a guest was about to visit. If it washed its body, it meant it would rain. If a cat slept very close to the hearth, it meant it would snow. If a cat walked out of the house and ate grass outside, it meant that a drought would cause a bad harvest and prices would rise.

Horses were the boon companions of the people of Sassoun. This relationship was almost as intimate as a friendship. If a rider noticed that a horse was reluctant to continue traveling, he or she would surmise that there was danger on the road ahead, and would turn back. Horse bells were hung in the fields as amulets to protect crops from evil eyes. According to popular belief, flaming horses lived in the impregnable reaches out of the mountains. Only heroes and the extremely courageous ever had a chance to lay eyes on these creatures.

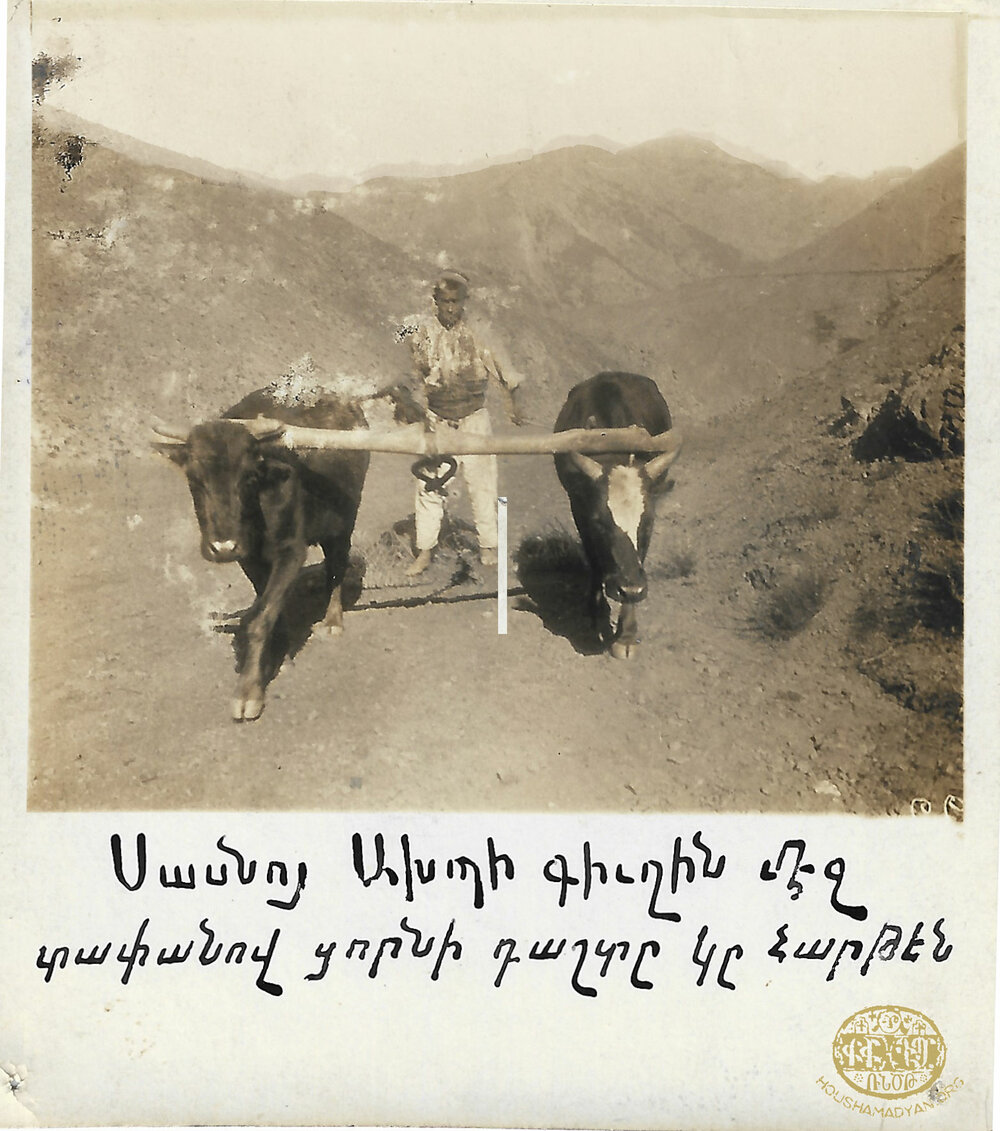

The ox was seen as a stalwart friend, a lifetime companion in the fields. When an ox died, its bell was hung on the wall of the barn, as an amulet.

The rooster was viewed as the bird that ushered in each new day. It chased away the darkness and brought in the daylight. The crowing of a rooster was the harbinger of dawn. The rooster was thought to crow only after hearing the heavenly rooster crow first. People believed that it strutted about slowly and proudly because if at any point its claws plunged into the soil, the whole earth would be destroyed. The rooster stood on only one leg when it climbed onto the roofs to make sure that the roof beams did not collapse. If it crowed in the evening, while perching, it meant that good health and prosperity would reign. But if a hen ever crowed like a rooster, it would be beheaded at the threshold as a harbinger of catastrophe or death.

Another belief held by the people of Sassoun concerned the planet, which they thought rested on the midsection of a giant fish. The movements of this fish were believed to cause earthquakes.

Bibliography

- Vartan Bedoyan Sassoun, Nakhapem Press, Yerevan, 2016, page 744.

- Yeghyazar Garabedian, Sassoun, Haybedahrad Press, Yerevan, 1962, page 203.

- "Asbarez", Tenth Anniversary Anthology, California, 1918, pages 246-257.