The Armenians of Hazari: Recreating the Demographic History

Author: George Aghjayan, 10/08/17 (Last modified: 10/08/17)

The village of Hazari (today known as Anıl) lies to the north of the town of Chmshgadzak (now called Çemişgezek). Adminstrative borders changed frequently, but Chmshgadzak was most often associated with the Dersim region that was attached to the Mamuret ul-aziz [Harput/Kharpert] province during the last century of the Ottoman Empire. Hazari was entirely Armenian before the genocide begun in 1915. (1) At its peak, Hazari contained as many as 500 Armenians in 70 households. The village had a functioning church, Surp Yerrortoutiun (Holy Trinity), and school. On the eve of the genocide, the population had already declined to under 400. (2) Since 1923, the population of Hazari has never fully recovered from the loss of the Armenians. The 2000 census of the Republic of Turkey stated the population of Hazari was only 85 people (42 males and 43 females). (3)

Sources

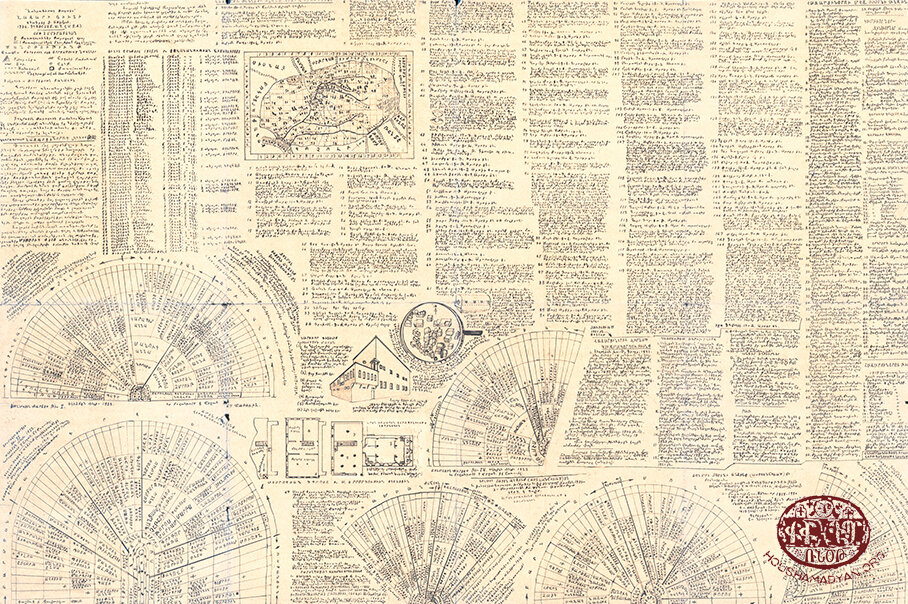

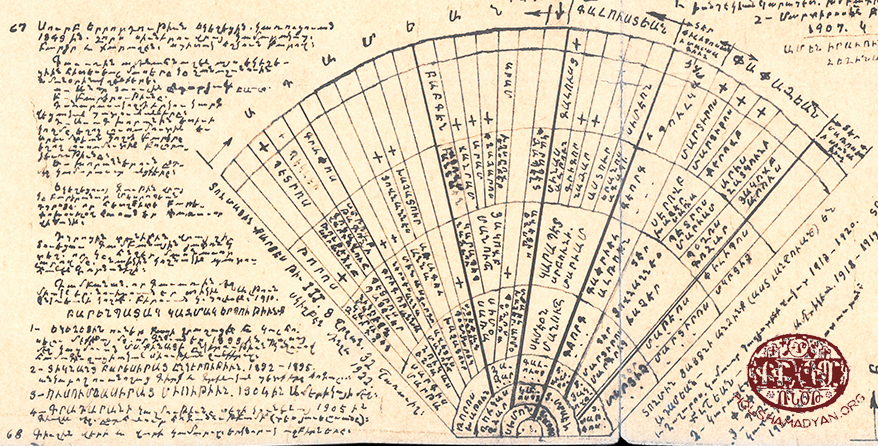

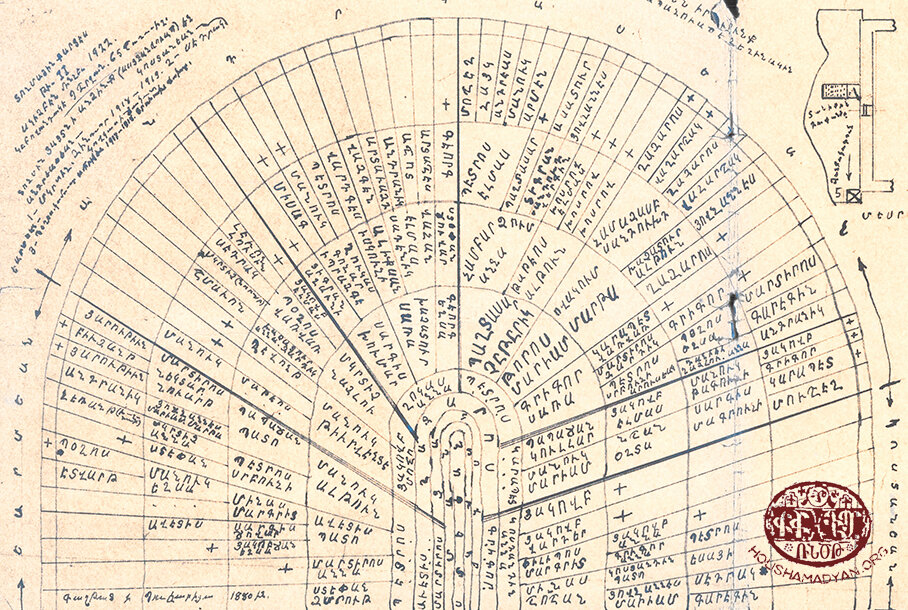

After the genocide, Hovhannes Ajemian compiled a significant amount of material on the Armenian villages of Chmshgadzak. While some portions were referenced in two books on the Chmshgadzak region, most of Ajemian’s work remains unpublished. (4) Included with the Ajemian material were a number of genealogy wheels, a way of presenting the family trees beginning with the oldest known ancestor and fanning out for descendants. As more of the genealogy wheels come to light, it is clear many still remain in private hands.

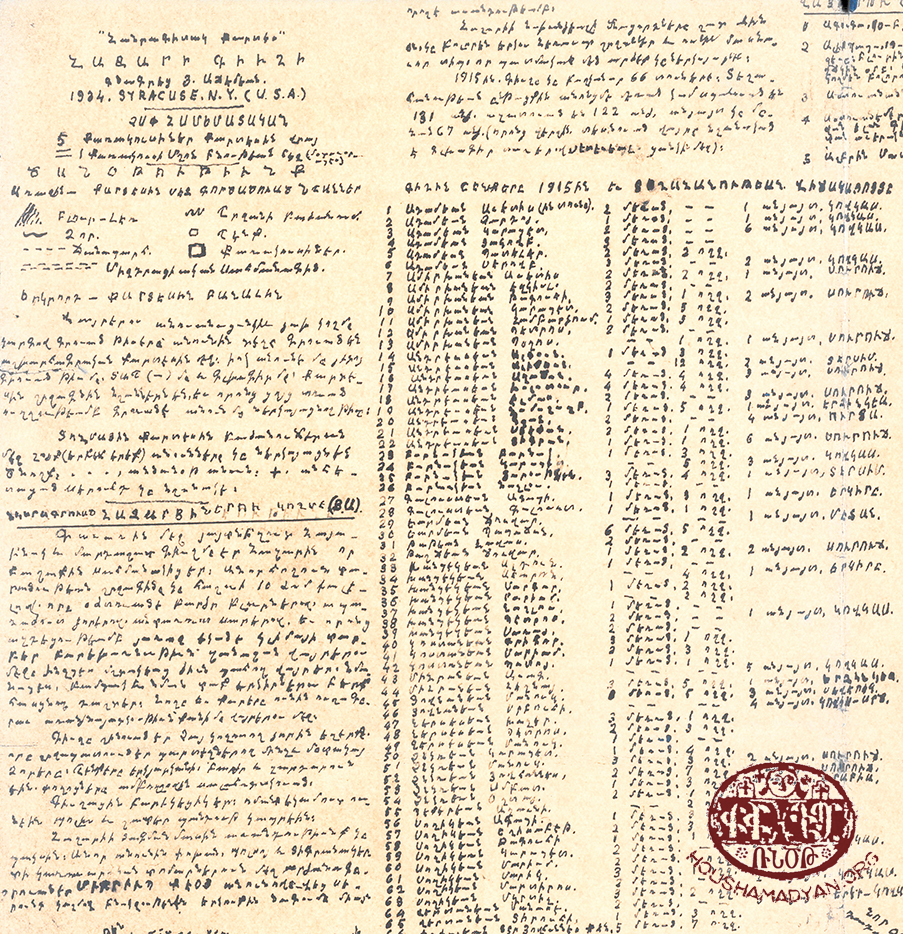

Recently, Vazken Andréassian, grandson of the author of a series of books on Hazari, shared six genealogy wheels detailing the origins of 21 surnames associated with the village. (5) The information contained in the family trees is very detailed and in most cases dates to prior to 1800. I have compared the information in the wheels with an Ottoman census undertaken in 1840. (6) The comparison offers an important glimpse into the strengths and weaknesses of each source.

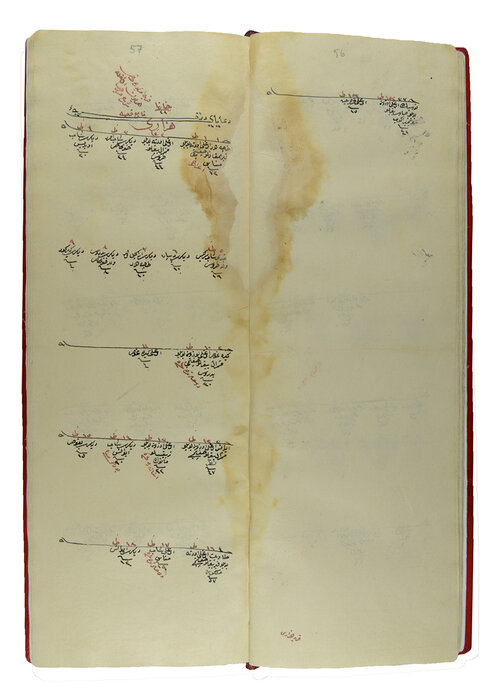

Beginning around 1830, a renewed effort by the government of the Ottoman Empire at registering the population was begun with the goal of taxation of non-Muslims and military conscription for Muslims. As such, only men were enumerated. It was only much later that women were included. A full treatment of the Ottoman registration system is outside the scope of this article. (7) Only one non-Muslim register from 1840 for the region of Chmshgadzak is available in the Ottoman archives. While later registers surely exist, particularly one recorded around 1906, researchers are not currently allowed access to this most crucial census.

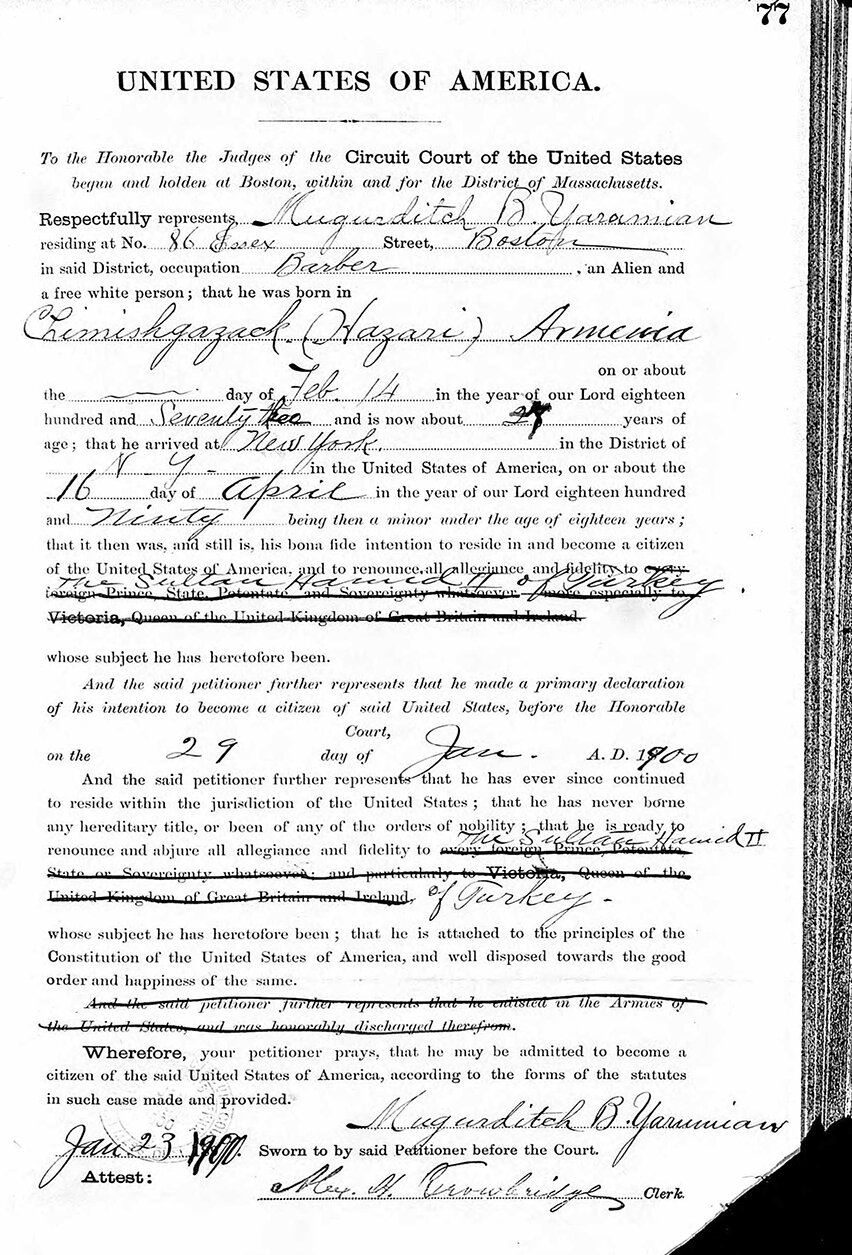

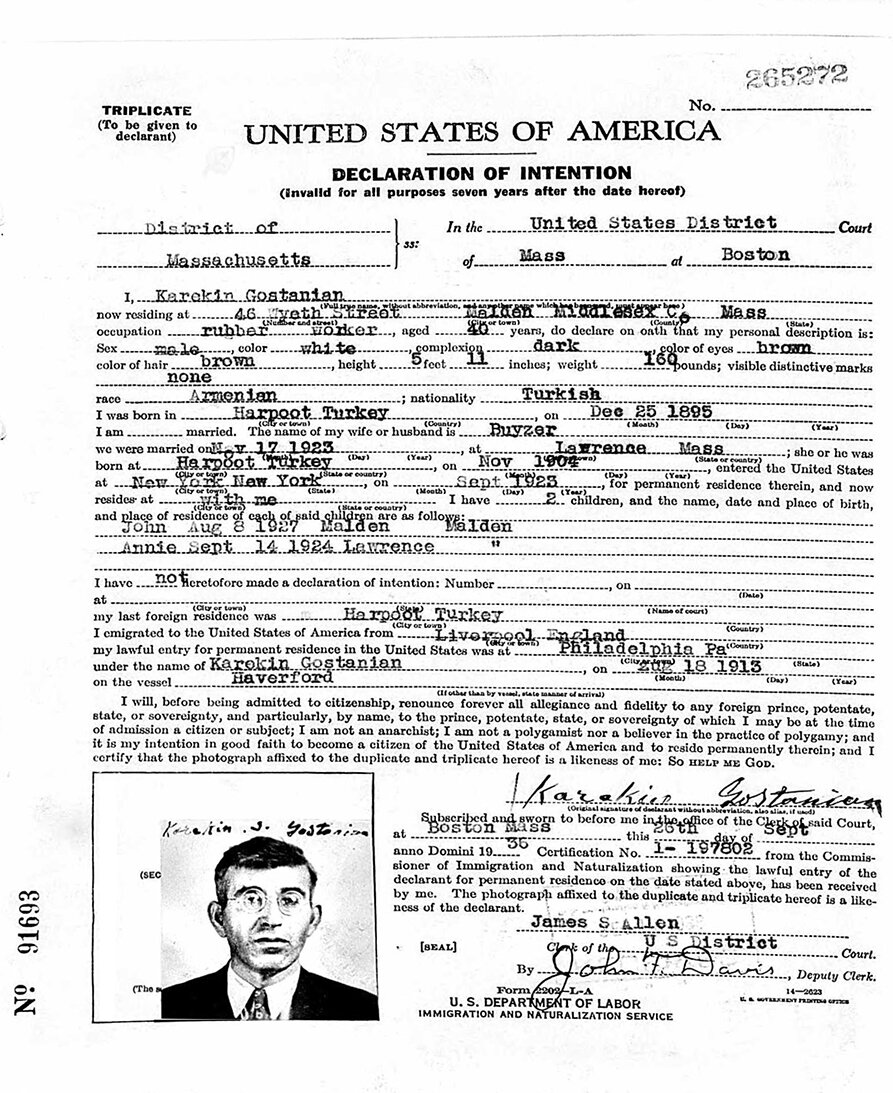

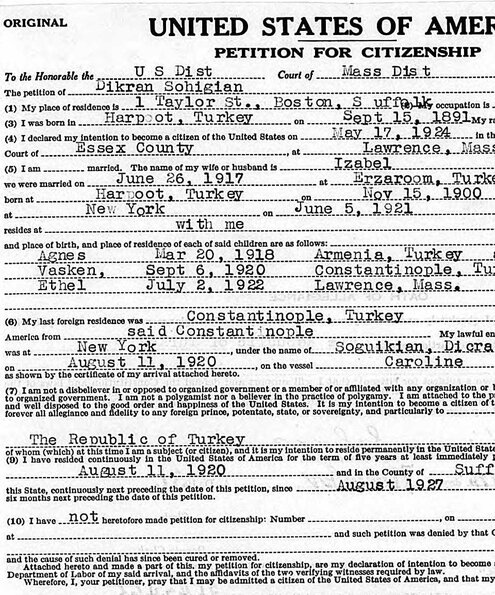

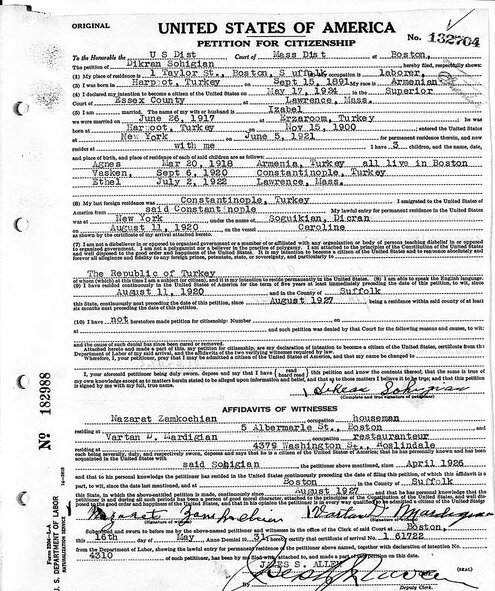

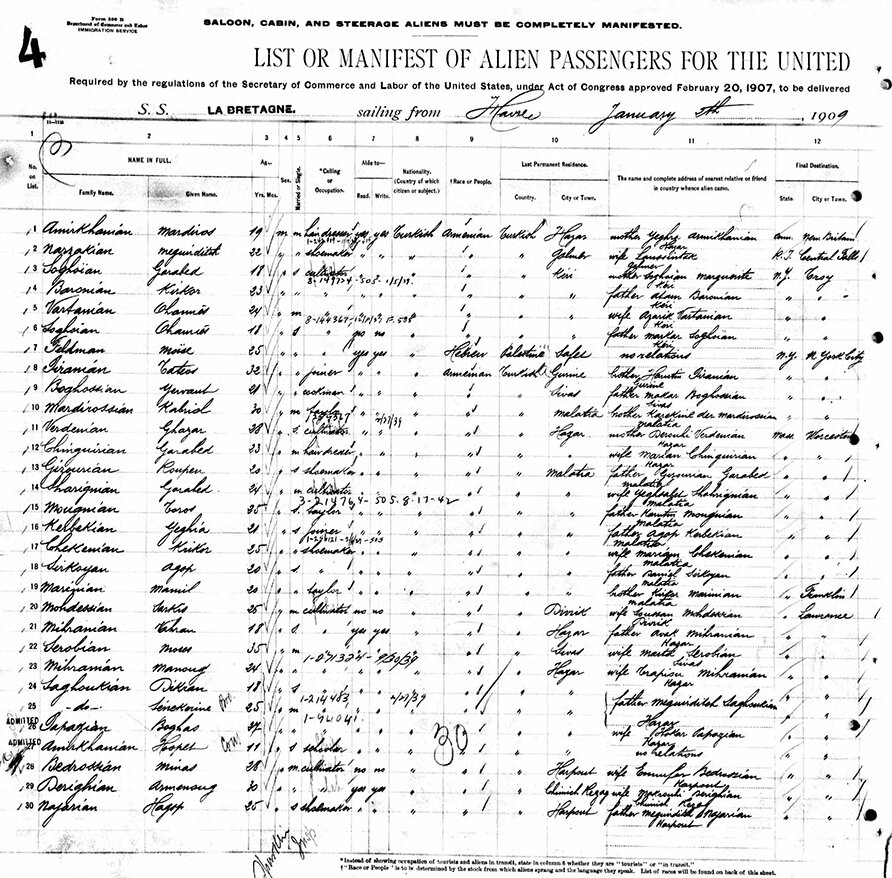

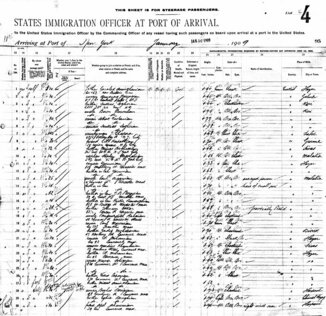

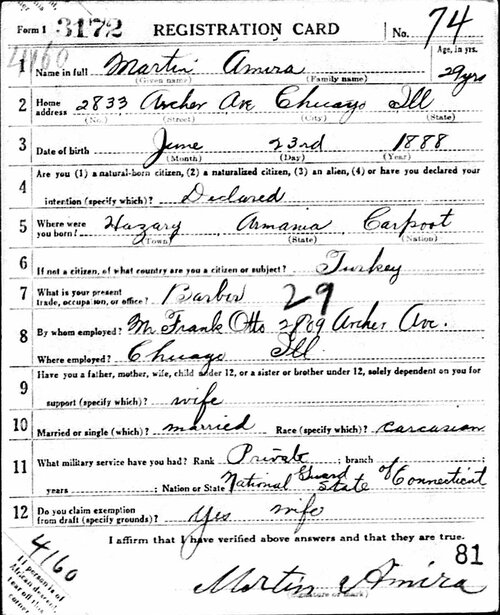

In addition to the genealogy wheels and 1840 Ottoman census, I have culled relevant data from the records of those who migrated to the United States. Of particular note is that a great many of the men from Hazari traveled to Lawrence, Massachusetts. The tenement houses at 230 and 280 Common Street served as the initial home for these men. Nine men from Hazari arrived in the United States on the same ship, the SS La Bretagne on 11 Jan 1909. While not exhaustive, the U.S. records are useful in adding context to the overall trees.

There were three primary resources used for the United States records. First, Mark Arslan’s Armenian Immigration Project website was an indispensible tool. (8) Arslan has gathered information on Armenians from ship manifests, census records, military records, etc. Of particular value is his combined query of the entire database by standardized surname. In addition, ancestry.com and familysearch.org were utilized to access source records.

Methodology

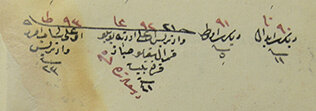

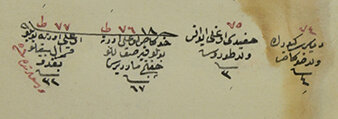

The 1840 Ottoman census was recorded in Ottoman Turkish. Thus, a thorough translation of the records was required. (9) The surname convention varied greatly by village in the Ottoman system. Most often, the household identification used in 1840 was not the same as the surname of the family post-genocide. Especially in small villages, like Hazari, the head of household was simply identified by the name of the father.

Some families retained the patronymic surnames. For example, it was easy to identify the Nersesian family as the census only included one man named Nerses. However, additional matching names were required to gain comfort that the household did, in fact, contain the presumed family. The household containing the priest’s family assisted in identifying an additional match.

For other households, I had to rely completely on the matching of men’s names with the genealogy wheel. The accuracy of oral tradition lessens with the passage of time. Thus, there was a certain subjective threshold that I required to attain confidence in the matching of 28 census households with 21 genealogy wheel families.

With some level of confidence, I identified 14 of the 21 genealogy wheel families in 15 households of the Ottoman census. Possible connections are offered for an additional 3 families with much less confidence. This left 4 families and 10 households unidentified. Two of the families, Der Pilibosian and Der Mateosian, are stated to have left the village, but a year of emigration was not given to know whether it was prior to 1840 or not. I speculate on a couple of others, but some questions are just not solvable.

The unidentified households from the census could be additional families that emigrated from the village. It could also be that their male lines died out prior to the oral tradition that formed the basis of the genealogy wheels. Without more current Ottoman census records, especially those that include women, it is impossible to determine.

A similar methodology was utilized for United States records. Since many names are common, additional confirmation was required prior to accepting the record as related to Hazari. Of course, if Hazari was stated as the place of birth, that was accepted. In addition, the ship manifest on arrival was a key source as often they include the closest relative remaining in the place of origin as well as the name and relationship of those they were joining in the U.S. Family relations, living at the same address, etc. increased the confidence level. The wife or parent remaining in Hazari or the brother they were joining in the United States served as additional important validating points. While most of the men traveled to Lawrence, Massachusetts, that was not absolute. For instance, some traveled to New York and Connecticut.

Because of the various ways Armenian names and surnames can be transliterated into English, wildcard searches were often employed. For example, the suffix “*an” was used in searches in order to return surnames ending in “ian”, “ean” or “yan.”

More complex searching was also used, for instance limits based solely on a range of years of birth and immigration year might be used to locate a ship manifest. However, even the best of efforts would sometimes not yield any results. The gaps were not significant and do not compromise the extensive amount of information. I was able to identify 137 men from Hazari in over 500 records from the U.S.

Armenian Surnames

The origin of Armenian surnames fall into certain categories. The most common by far are patronymic surnames – those rooted in male first names, such as Garabedian, Melkonian, Kevorkian, etc. Other surnames are based on occupation, most often using the Ottoman Turkish word. Examples of this include, Demirjian (blacksmith), Najarian (carpenter), Kazanjian (cauldron maker), Berberian (barber), etc. Some surnames are based on the town of origin for those that had migrated – Palutsian, Marashlian, etc. The “ts” suffix being Armenian while the “li” suffix is Turkish. Still other surnames were descriptive of a physical trait, for instance Topalian (lame) and Altiparmakian (six fingers).

Armenian surnames are rarely perpetuated from ancient noble families. Though some do exist, for example, Suni and Artzruni. In some cases the origin may in fact be patronymic. For example, Mamigonian is not necessarily linked to nobility.

When working with the various records, it becomes obvious that the popularization of Armenian surnames was a recent phenomena. Surnames are simply a way of more specifically referencing a particular person. The need arises in business and particularly in dealings with the government. Thus, the Ottoman registration system begun in 1830 most likely served as the impetus for Armenian surnames. Which Hagop? Hagop the son of the priest (Keshishian) or Hagop the son of Bedros (Bedros) or lame Hagop (Topalian) or Hagop from Palu (Palutsian). As such, surnames could and did change frequently. The son of Hagop Bedrosian becomes Hagopian and so on. As households grew and divided, the descendants of different sons might go by different surnames. For instance, Hagop has two sons, Kevork and Bedros. The descendants of Kevork might go by Kevorkian or Hagopian. Similarly, the descendants of Bedros might go by Bedrosian or Hagopian. Larger cities would be earliest to adopt more nuanced surnames.

Surnames continued to change, sometimes even after the genocide. As can be imagined, this complicates research and the ability to conclusively identify individuals.

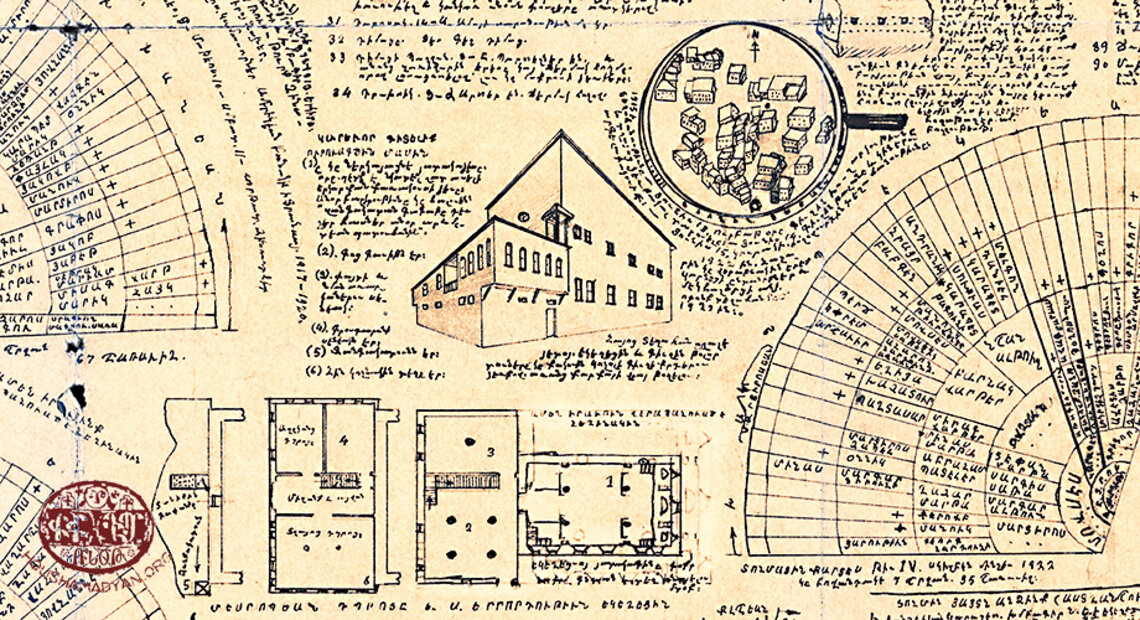

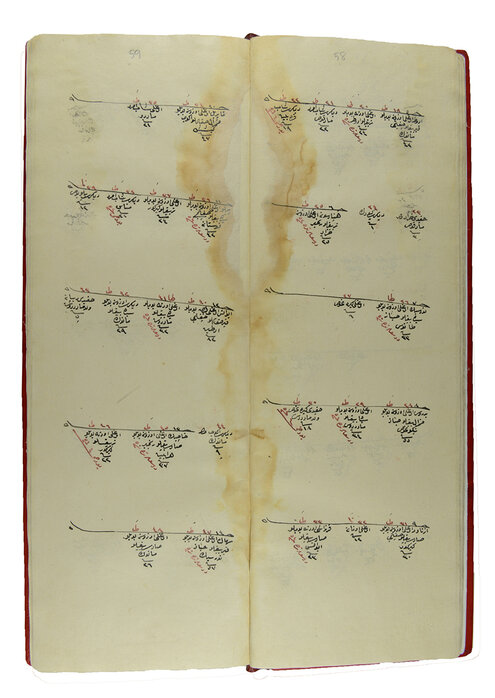

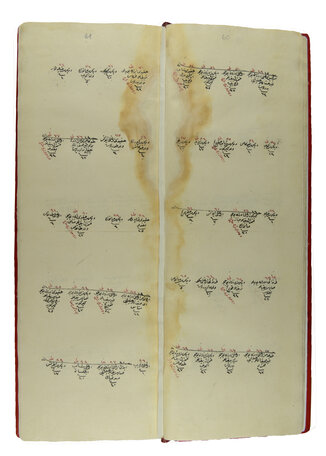

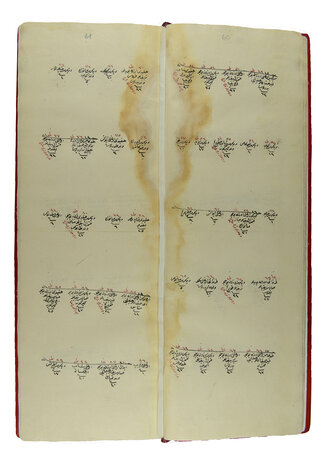

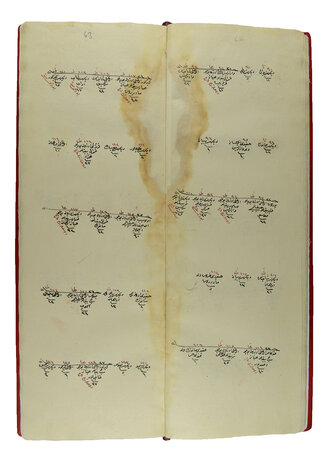

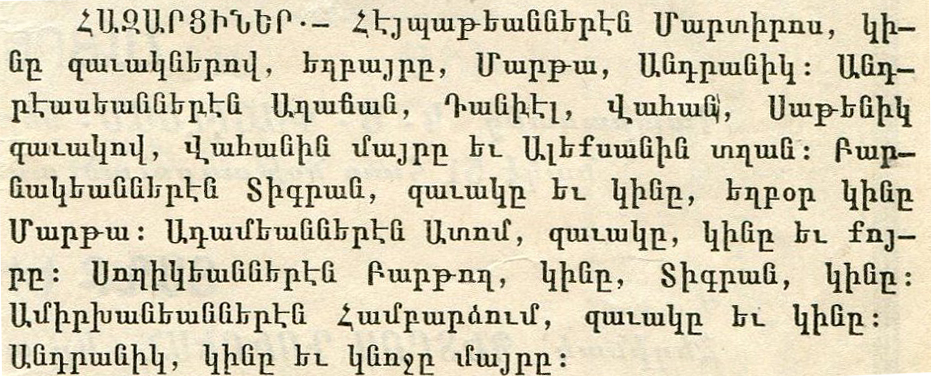

Images from the 1840 Ottoman census

1840 Ottoman census

The 1840 Ottoman census for Hazari details 129 Armenian men in 28 households. Information on tax classification, height, facial hair, occupation and age were included. While the sample size is small, some interesting details can be observed.

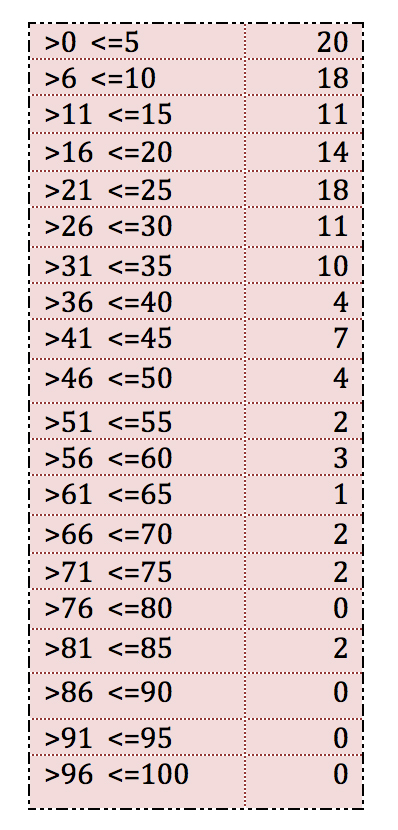

The following table contains the number of males in 5-year age groupings:

The small sample size and lack of secondary source make it difficult to draw any conclusions from the data. There are most assuredly misstatements of age as occurs in all censuses, particularly when age is recorded as opposed to year of birth. In addition, age heaping is often found in census data. For instance, there can be tendencies to state ages rounded to the nearest quinquennial age or to have heaping at ages just below the age of taxation or military service.

There were 90 males in the census whose fathers were also listed. This allowed for an analysis of the age of the father when the son was born. The data is incomplete as females and children that have died or left the village were missing. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the average age of the father was 27 when the sons were born (i.e. average years per generation). The youngest age recorded for the father upon the birth of a son was 15 and the oldest 53. Again, these are noted while still understanding the limitations of age data and the small sample size.

The average years per generation increased to 30 years when including data from the United States. A combination of reasons can be offered for the increase. First, the eldest son would inherit the responsibilities for the household and, thus, the youngest sons would have been more likely to travel to the United States. Second, the U.S. records include those born after the extended rupture caused by the genocide. Third, throughout the 19th century, the average age when having children could have increased along with life expectancies. Lastly, it might simply be attributed to the small sample size.

Any boy age 11 and over was taxed. There were three tax classifications (high, middle and low). In Hazari, 8 men were classified as high income, 79 as middle income and 4 as low income. Those classified as low income were the youngest, ages 11 or 12, although some 12-year old boys were classified as middle income.

Of those where height was mentioned, nearly 60% were classified as tall. This was extremely unusual. Only two men were classified as short. Some were classified as simply youth. Occasionally, records from the United States would include height. Based on a sampling of these records and assuming descendants generally grew to a similar height, it would seem that approximately over 5’8” was deemed tall and below 5’3” was short.

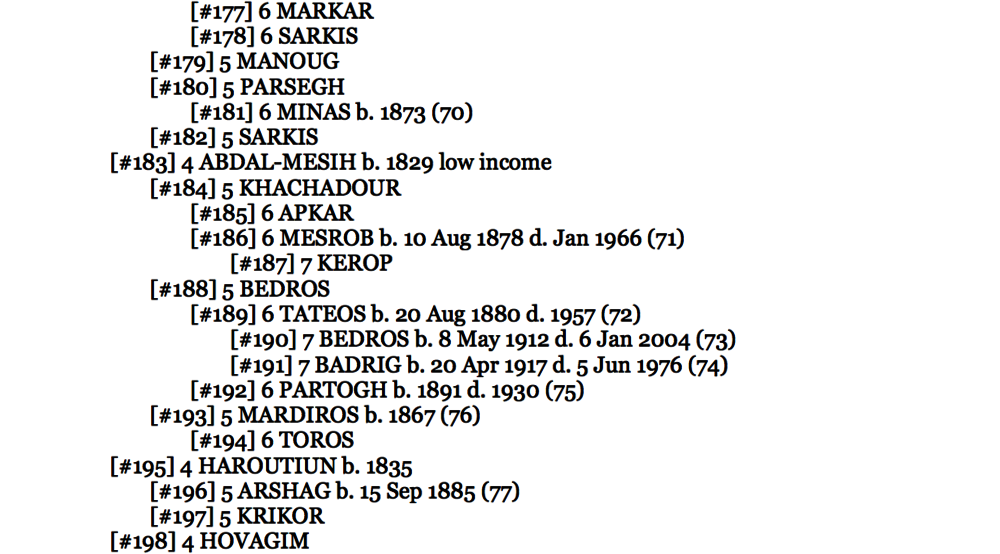

Facial hair was supplied for those over the age of 20. Those 25 years old and younger were often just described as beardless or with a beginning mustache. The following table breaks down the number of men by type and color of facial hair.

There was one priest in the village. All other men were classified as farmers, farmhands, or shepherds.

Over 30% of the recorded males had left for Istanbul for work. This was a common practice throughout the 19th and early 20th century. While many traveled as bachelors, most often it was recently married men, those with newborns or those with pregnant wives to ensure they would return to the village. They ranged in age from 15 to 57 years old with an average age of 30. On average, they had been gone 4 years. Thus, for those where the year was recorded, their average age had been approximately 26 when leaving for Istanbul. By comparison, of the 84 ship manifests I found for arrival in the U.S. prior to 1915, the average age of the Hazari men was 24.

Thus, it can be seen how the immigration to the U.S. was a continuation of a practice already in place for nearly 100 years, if not longer. The 1840 census records show Adana and Istanbul as the primary destinations for work for the men of Chmshgadzak. The U.S. would replace Adana and Istanbul for a great many men beginning in the late 19th century. As some men never returned from Adana and Istanbul, so to men stayed in America.

Family Trees

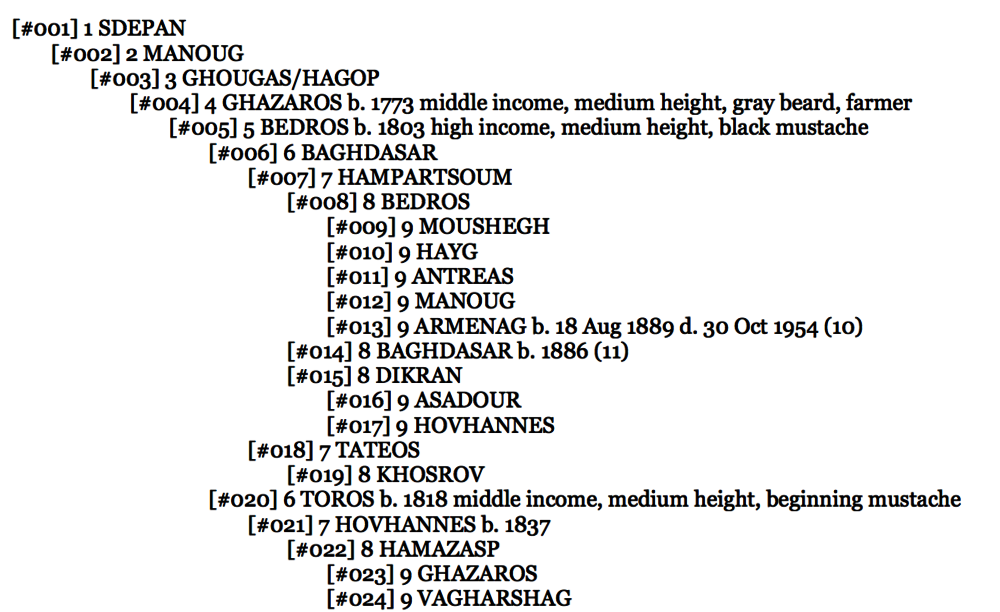

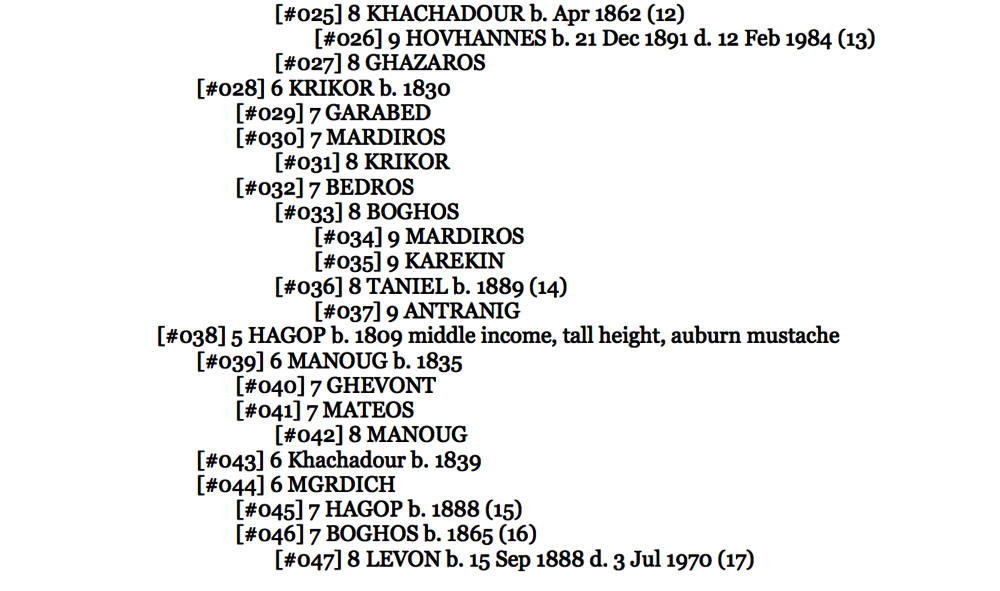

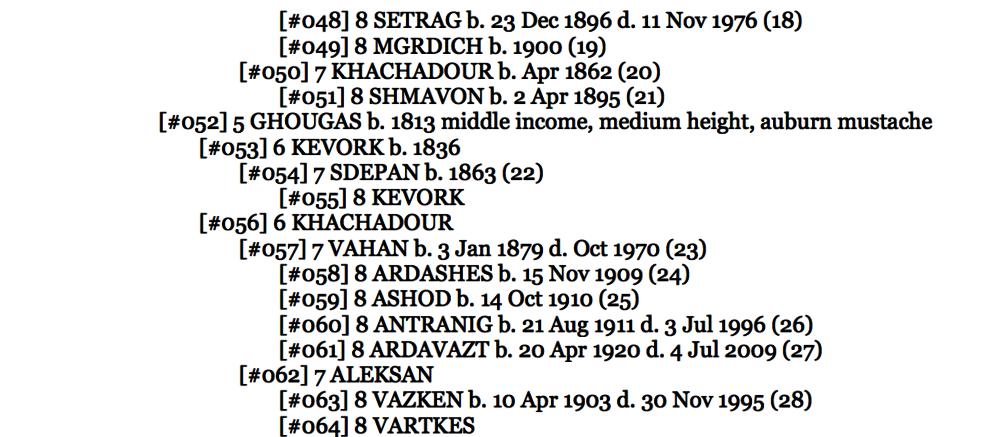

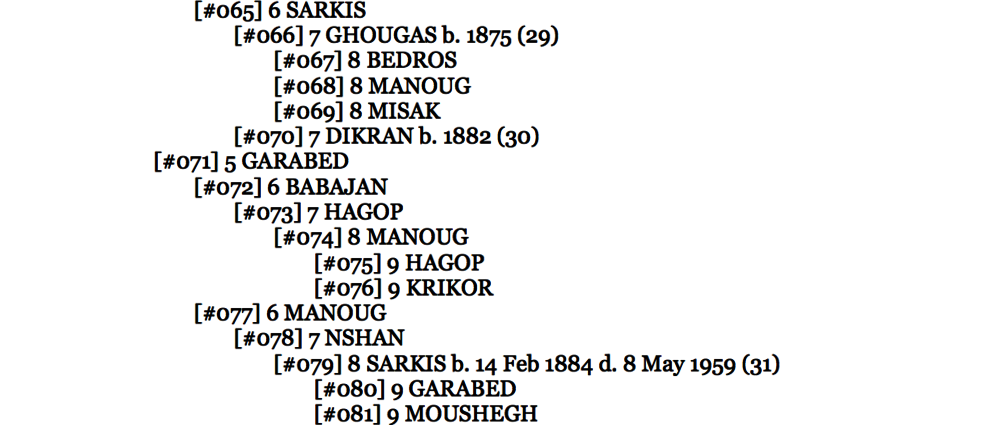

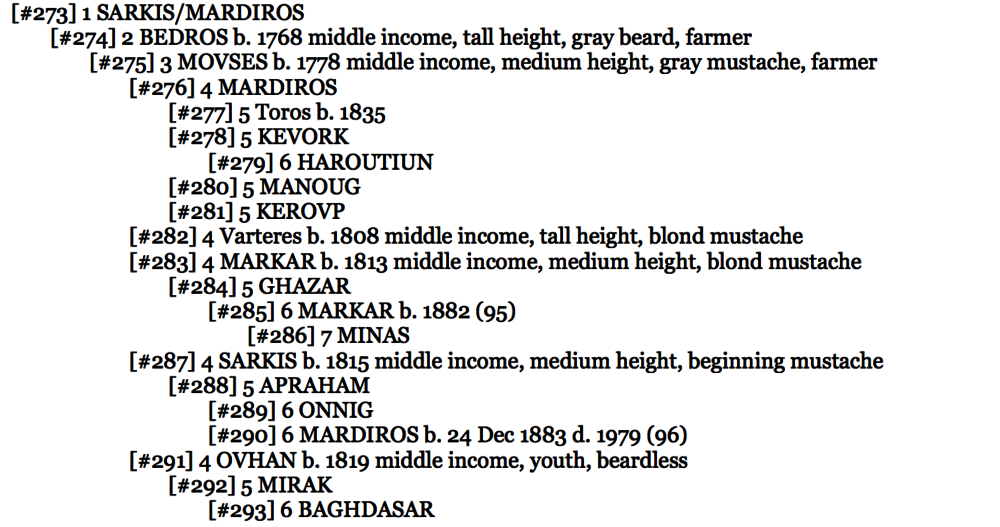

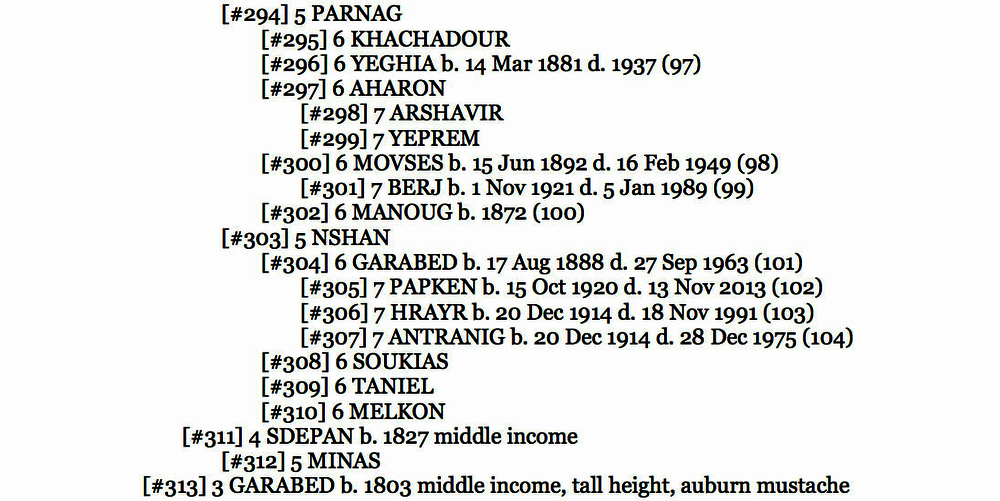

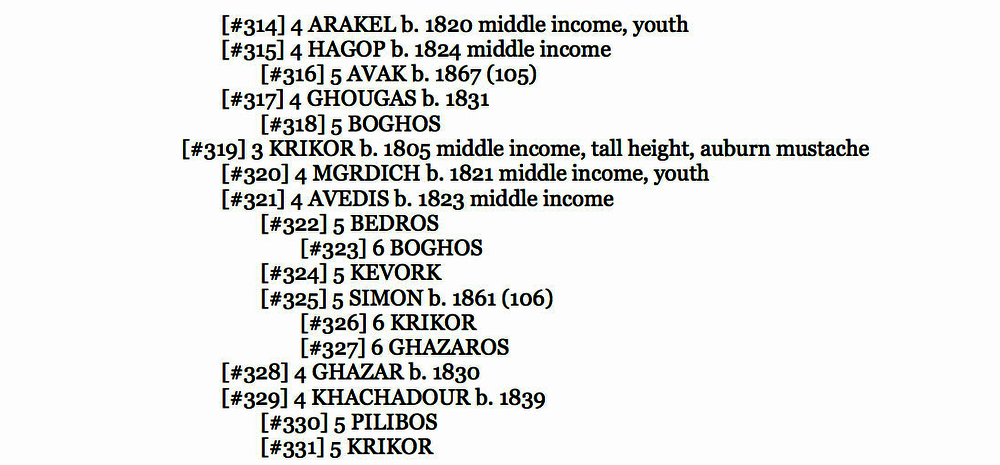

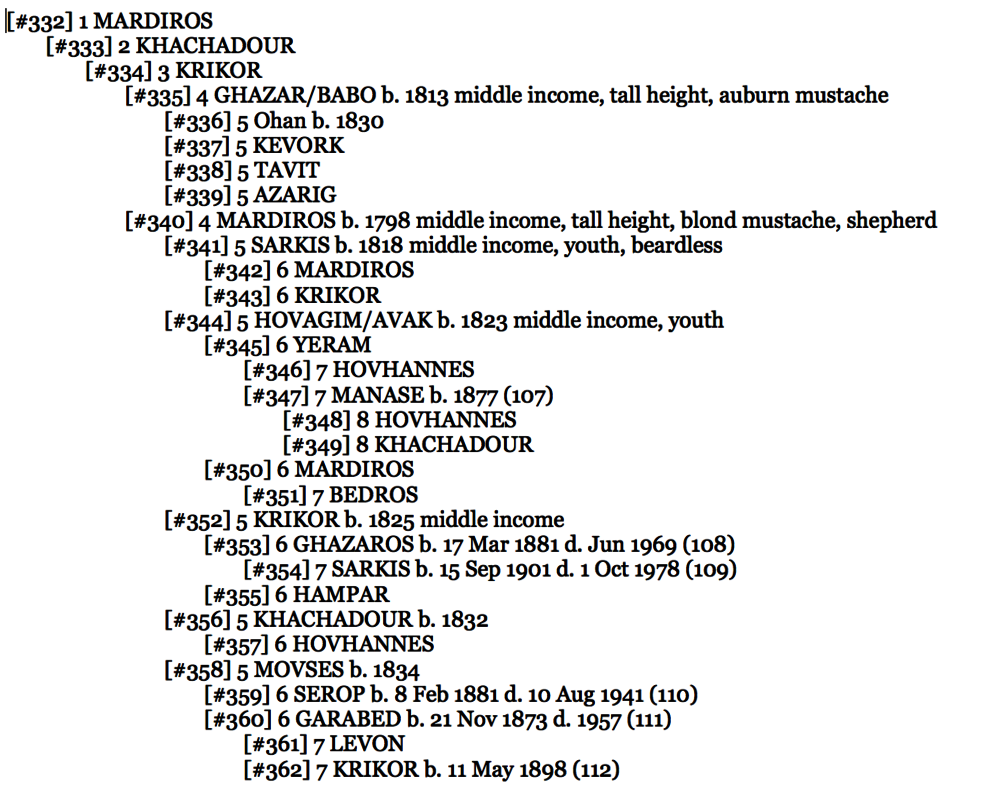

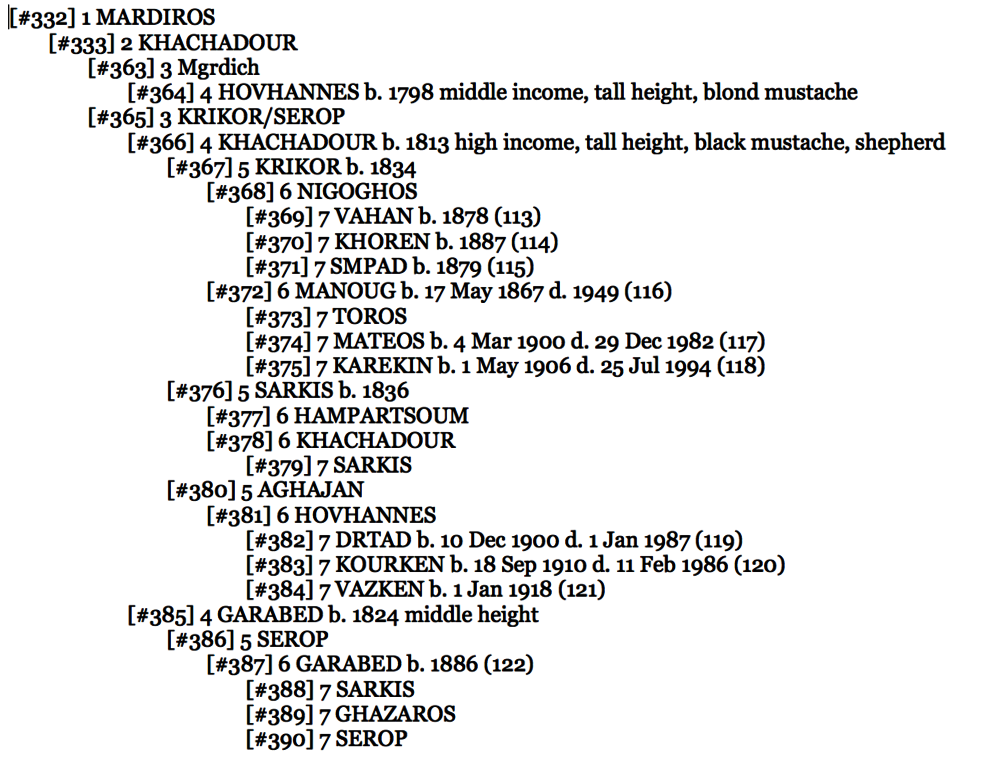

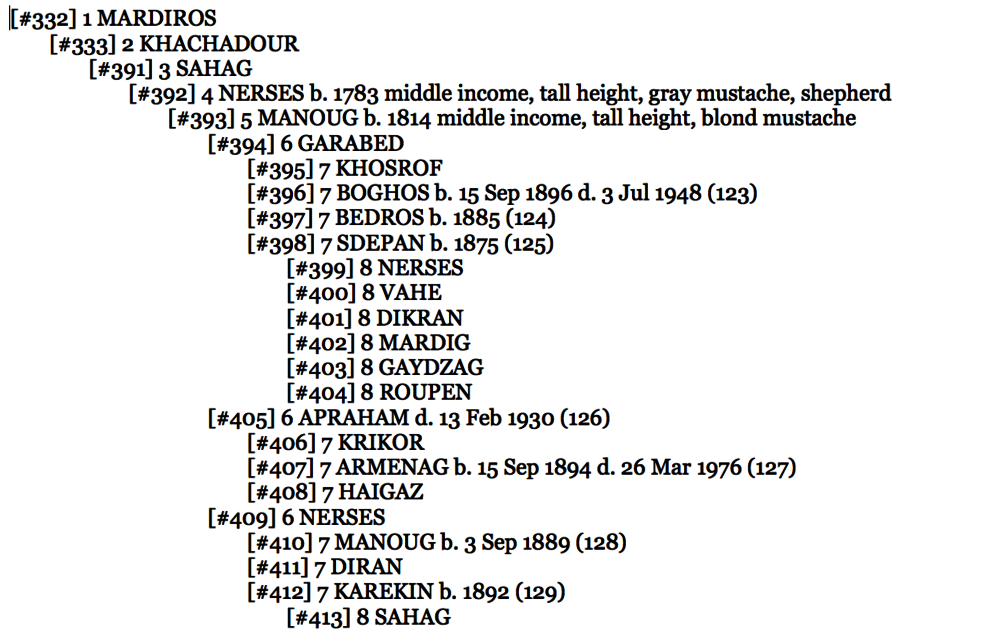

For the representation of the family trees, the initial number in brackets is a unique identifier for each person. The second number represents the generation in the family. To follow the line of ascent, follow the next lowest number generation above the person. I have included a graphical representation of the family tree to aid in visualizing the family relationships. Capitalized names are those who appear in the genealogy wheel. If a year of birth prior to 1840 is given, the person is listed in the 1840 Ottoman census. Any descriptive data is also from the census. There were cases in the genealogy wheel where multiple sons carried the same name. This was assumed to be when a son was named for a previously deceased brother. While certainly there is value in naming each duplicate son, for this purpose I have only listed the name once.

Yarumian/Antreasian/Gosdanian Wheel

The first wheel includes, appropriately, the Antreasian family, the family so closely associated with Hazari. In fact, three separate surnames (Yarumian, Antreasian, and Gosdanian) have origins in this one family according to the genealogy wheel. Based on the ages in the Ottoman census, we can speculate that the ancestor of this extensive clan, [#001] Sdepan, lived in the early 1700’s.

Click HERE to see the Yarumian/Antreasian/Gosdanian Wheel.

Antreasian Branch

Click HERE to see the Antreasian branch.

Surprisingly, the source of the surname, Antreasian, cannot be determined from the data (i.e. there is no person with the name Antreas). The Ottoman census detailed 10 men across 4 generations. One child in the census, [#043] Khachadour, was not found in the genealogy wheel. Presumably, he died in infancy and maybe was not known to future generations. Another equally likely possibility is that the father of Khachadour was misidentified as Hagop when it should have been Ghougas, thus he would be the same person as [#056].

The branch under [#071] Garabed cannot be readily identified in the census. Household #21, headed by a Garabed born in 1799 and having a son Manoug born in 1828, is a reasonable possibility. However, that is where the similarities end. Thus, I have left the link as inconclusive.

Based on the years of birth for [#005] Bedros and [#013] Armenag, it would seem that [#006] Baghdasar must have been alive in 1840. Yet he is not listed in the Ottoman census.

[#021] Hovhannes is listed as Ovagoum (variant of Hovagim) in the genealogy tree. In addition, the father of [#004] Ghazaros is given as Ghougas in the census while Hagop in the genealogy wheel. As Ghazaros named two of his sons Hagop and Ghougas, it is difficult to say which name is appropriate for his father. Another possibility is that the father’s name was Hagop but that the family was known as Ghougasian from an earlier time.

On 9 Dec 1913 Mgrdich Antreasian arrived in the United States on the SS Rochambeau. It was stated he was joining his brother, Shmavon. I have assumed that [#051] Shmavon had lived in the United States from at least 1914 through 1925. Lacking a ship manifest for Shmavon, I have relied solely on his having lived with the other Antreasian’s from Hazari at 230 Common Street, Lawrence, Massachusetts. Yet, the genealogy wheel did not indicate Shmavon had a brother. [#049] Mgrdich arrived in 1919 based on the ship manifest stating he was joining his brother Levon at 230 Common Street. In addition, the middle initial “B” would seem to confirm Mgrdich’s father was [#046] Boghos. However, in 1922 Shmavon was living with Mgrdich B at 146 Maple Street, Lawrence. Adding to the confusion, there were three Mgrdich Antreasian’s listed in the 1924 Lawrence city directory and none of them were listed after 1925. While I have only listed [#049] Mgrdich in the family tree above, it is quite possible, even likely, that Shmavon had a brother Mgrdich that was missing from the genealogy wheel.

Already, the strengths and weaknesses of each source become apparent. The 1840 census is the only official Ottoman source available to researchers. As noted, more useful censuses taken after 1840 are inaccessible. The census supplies detail about individuals not found elsewhere. While suffering all the usual issues around age, still it supplies a valuable reference for the men recorded. In this case, the genealogy wheel covers a 200-year period enhancing the limitations of the census. Differences in names and relationships are not always resolvable, but clearly the two sources are complimentary and should be used together.

Of the 81 Antreasian men listed above, the estimated year of birth was determined for 32 of them. In analyzing the data from Unites States records, the average length of a generation was 29 years. The minimum length was 21.5 years ([#013] Armenag and his great-great-grandfather Bedros) while the longest was 41 ([#061] Ardavazt and his father Vahan). All of the results seem reasonable and, thus, the sources are generally in agreement. Interestingly, Vazken Andreassian assumed 25 years for each generation in estimating the years of birth in his family tree.

Gosdanian Branch

The Gosdanian family was another branch from [#003] Ghougas/Hagop. Already living in separate households in the census, the brother of [#004] Ghazaros was identified as Pilibos whereas the genealogy wheel stated his name as Krikor. Once again, based on the continuing tradition of naming boys after their grandfathers, it cannot be determined with certainty which name is correct. [#083] Gostantin would appear to be the source for the surname. This is an example of what has been discussed in regards to surnames. The Ottoman census identifies the household as Pilo oghlou, son of Pilibos. Yet the descendants took the name of Gosdanian for the patriarch of the clan in 1840. Here is the Gosdanian family tree as presented in both the census and genealogy wheel.

Click HERE to see the Gosdanian branch.

It cannot be determined whether [#084] Hagop from the genealogy wheel is the same as [#085] Krikor from the census. Otherwise, the sources are in agreement.

According to the available records, [#086] Minas was 52 years old when his son, Hovhannes, was born. That skews the average length of a generation (35 years) higher for the Gosdanian clan. Even excluding Hovhannes, the average was almost 32 years.

Yarumian Branch

One generation prior to the separation into the Antreasian and Gosdanian families, the Yarumian family was formed from Mardiros, son of [#002] Manoug. The origins of the Yarumian surname are unclear. Andreasian offers Heybetgants (meaning majestic) as an alternate name. (38) Presumably, the surname reflects someone having the name Yarum or a corruption of a similar variant. But Yarum does not appear in the genealogy wheel. Another possible explanation is that yarım means half in Turkish, though how that would lead to a surname is unknown. (39)

Click HERE to see the Yarumian branch.

The family should have been included in the 1840 census of Hazari. [#098] Bedros and his sons presumably were alive in 1840. However, the Yarumian branch cannot be clearly identified in the Ottoman census. There are a number of possibilities (household 12 in particular), but the discrepancies are too numerous to be conclusive. (48)

The genealogy wheel indicates [#119] Sdepan moved to Bulgaria in 1850. [#108] Herant/Khachadour apparently went by both names. The genealogy wheel lists both names. He entered the U.S. under the name Khachadour but used Herant (Harold) the remainder of his life.

Parounagian/Bekerian/Soghigian Wheel

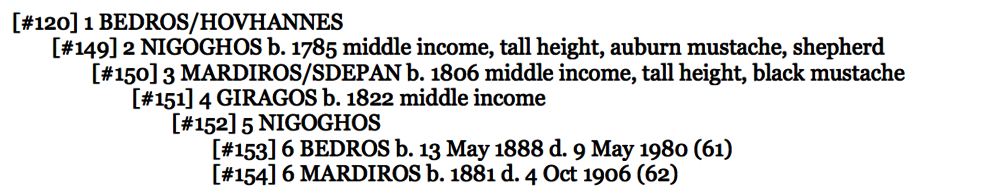

The next genealogy wheel details the common origin of three families, the Parounagian, Bekerian and Soghigian clans. Each clan was headed by a son of [#120] Bedros, the patriarch. Based on the ages of those contained in the Ottoman census, most likely Bedros was born in the mid-1700’s.

Click HERE to see the Parounagian/Bekerian/Soghigian branch.

Parounagian branch

Click HERE to see the Parounagian branch.

The Ottoman census stated the head of household as Nazar instead of [#121] Parounag. In addition, Nazar’s father was stated to be Hovhannes instead of [#120] Bedros. I have no explanation for these discrepancies other than that the men were known by various names. As the family came to be known as Parounagian, Parounag would seem to be fairly well verified. In addition, as we shall see from the other sons of Bedros, that also is at least corroborated. The three sons of [#121] Parounag are consistently named in the genealogy wheel and census and this was how I identified the family.

Similar to the other trees, the years per generation was 31 years when utilizing records from the United States. The longest generational gaps occurred with those born after the genocide.

Bekerian Branch

Click HERE to see the Bekerian branch.

In this case, the census confirms the name of the patriarch as [#120] Bedros. At the time of the census, the sons of Bedros had already split into their respective households. The Bekerian surname is associated with being single or a bachelor. In this particular case, I am not sure how the surname came to be associated with this branch of the family. The household map contained in Antreasian’s book seems to list the Bekerian clan under the name Depoian. As Depo is an alternate form of Sdepan, it would seem that the family was also known in the village by this surname.

In the census, the son of [#149] Nigoghos is given as Mardiros whereas in the genealogy wheel the name is given as Sdepan. While not conclusive, the recurrence of Mardiros in the family could indicate it is the correct name. Possibly the most probable explanation is that Sdepan was another son of [#149] Nigoghos that never married. Maybe upon the death of his brother Mardiros, Sdepan adopted his son Giragos. Thus, both the Bekerian and Depoian surnames would be applicable and Mardiros and Sdepan should be listed as brothers as opposed to the same person.

[#153] Bedros appears to have been the only member of the family to survive the genocide. Sixty-six years separated the birth of Bedros from the birth of his grandfather, Giragos, a reasonable 33 years per generation. Bedros and his wife, Aghavni, did not have any sons. Thus, it would appear the Bekerian surname from Hazari has died out.

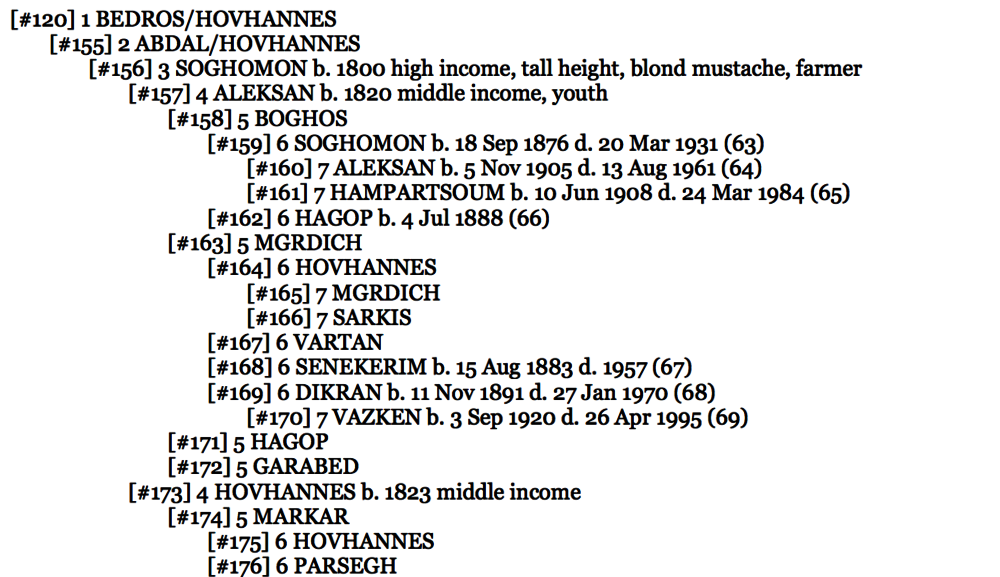

Soghigian Branch

Click HERE to see the Soghigian branch.

Clearly, the Soghigian branch obtained its name from [#156] Soghomon. The census identified him as Soghig as well. His father was identified in the census as [#155] Abdal, yet the genealogy wheel identified his name as Hovhannes. Again, we see grandsons carry both the name Hovhannes and Abdal. Thus, it is difficult to say which name is accurate or if both names are applicable. Abdal or Abdal Mesih (servant of the messiah or servant of Christ) is the name of a Syrian saint that is also venerated by the Armenian church. Based on the known years of birth, it would seem likely that [#155] Abdal was the oldest of the three sons of [#120] Bedros.

Soghomon’s son, [#198] Hovagim, was not listed in the 1840 census and, thus, may not have yet been born. It appears he died without leaving any surviving male offspring. Soghomon’s other four sons are consistently named in the census and genealogy wheel.

The United States records are mostly consistent with the Ottoman census dates of birth. The greatest generation gap was between [#195] Haroutiun and his son, [#196] Arshag. Thus, it could be that Arshag was born earlier than 1885 as implied by the 1920 census. Overall, the average number of years per generation was a reasonable 31.

The descendents of [#188] Bedros went by the surname Bedrosian as opposed to Soghigian.

Atamian/Klshian/Kalousdian/Der Pilibosian/Papazian/Der Mateosian Wheel

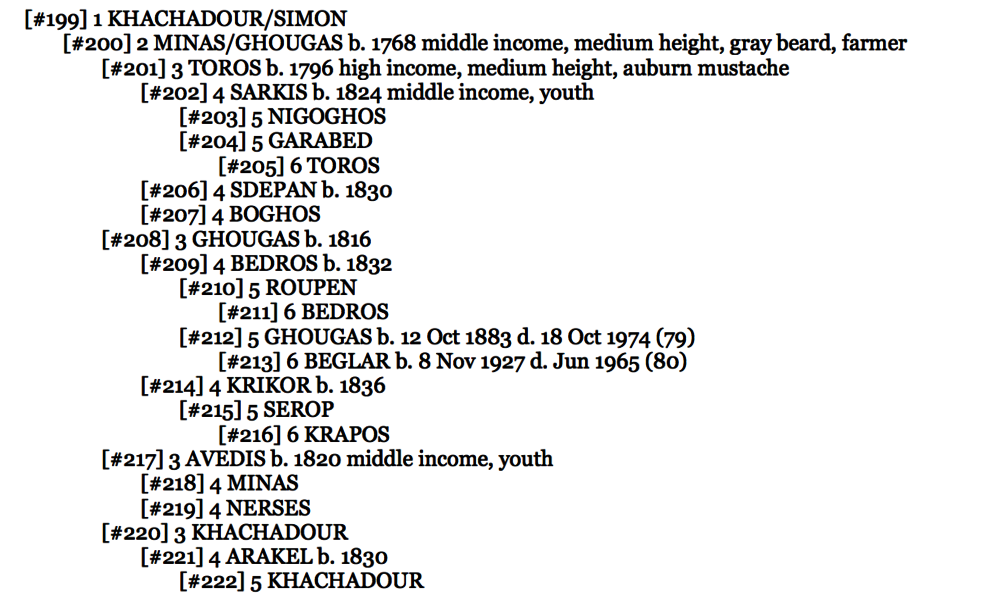

This extensive tree begins with, presumably, two brothers, Simon and what looks to be Margos. (78) There are some significant discrepancies between the genealogy wheel and the Ottoman census. The family tree presented below represents my interpretation of the available information. Unfortunately, some portions of the family cannot be clearly identified in the census, thus limiting what can be determined conclusively. From the available dates of birth, it can be presumed that Simon and Margos lived in the early to mid-1700’s.

Click HERE to see the Atamian/Klshian/Kalousdian/Der Pilibosian/Papazian/Der Mateosian Wheel.

Atamian/Klshian Branch

Click HERE to see the Atamian/Klshian Branch.

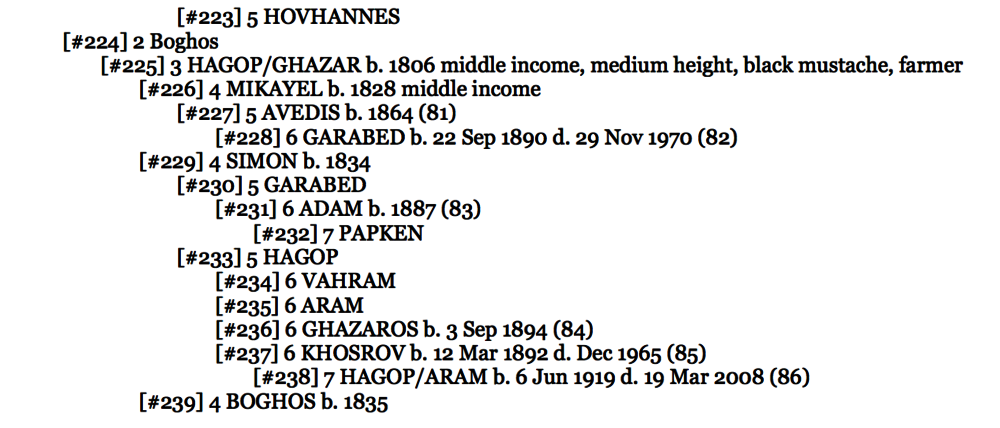

The Klshian branch of the family begins with [#226] Mikayel. The rest of the family is shown as Atamian. The genealogy wheel deviates from the census almost immediately. The father of [#201] Toros was alive at the time of the census and named Minas whereas the genealogy wheel lists his name as Ghougas. Similarly, the father of [#226] Mikayel, [#229] Simon and [#239] Boghos was alive at the time of the census and his name was given as Hagop whereas the genealogy wheel lists his name as Ghazar. In addition, Hagop’s father was given as Boghos in the census. According to the wheel, Hagop and Toros should have been brothers, but instead it appears their fathers were brothers.

The next significant discrepancy is that [#208] Ghougas, [#217] Avedis and [#220] Khachadour were not [#201] Toros’ sons but instead his brothers according to the census. Ghougas was 20 years younger and Avedis 24 years younger than Toros. Once [#200] Minas had passed away, it could be that Toros became essentially the father figure for his brothers and the relationship was remembered that way in oral tradition. At the time of the census, Khachadour had already passed away. Clearly, there are other possible explanations including the census being in error.

It is interesting to note that already in 1840 the family had split into two households. The family of [#200] Minas/Ghougas formed one household and the other contained the descendants of his brother, [#224] Boghos.

[#228] Garabed is known to have had a son, Aram, born in Massachusetts on 22 Jun 1927. It is unclear why he was not shown on the genealogy wheel. It is possible that [#238] Aram from the genealogy wheel really should have been listed as Garabed’s son instead of Khosrov’s son. The 1920 census as well as the Massachusetts birth index indicate Khosrov’s son as Hagop. He would later be known as Raymond H. Atamian.

Once again, the United States records are consistent with the Ottoman census records. The average years per generation was 32 years. The longest gap was between [#212] Ghougas and his father, Bedros (51 years).

Kalousdian Branch

Click HERE to see the Kalousdian branch.

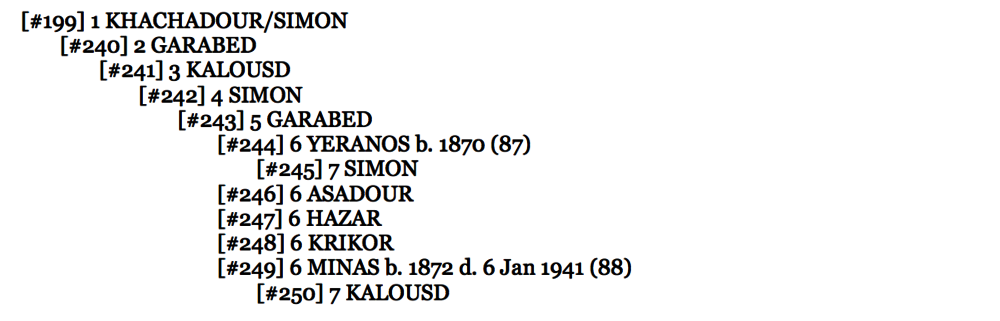

I have not been able to conclusively identify the Kalousdian branch in the 1840 Ottoman census. It seems highly likely to be household #19, although numerous differences exist. As a result, it is difficult to say much about the information presented in the genealogy wheel. Based on the known ages of others in the wheel, both [#240] Garabed and [#241] Kalousd could have already passed away by the time of the 1840 census. In addition, [#243] Garabed may not have yet been born. At the very least though, [#242] Simon should have been recorded in the census. So, if it is not household #19, either this family was excluded from the census in error or they avoided it so as not to incur tax debt. Another possibility is that the census takers missed the Kalousdian men because they were working outside the village.

While both Minas and Yeranos lived in the United States, I could not find any records for their sons, Simon and Kalousd. In the case of Minas, his wife Altoun joined him in 1922, but her ship manifest makes no mention of Kalousd. The genealogy wheel indicates this male line died out and it can be presumed that Kalousd was killed during the genocide.

Der Pilibosian branch

Click HERE to see the Pilibosian branch.

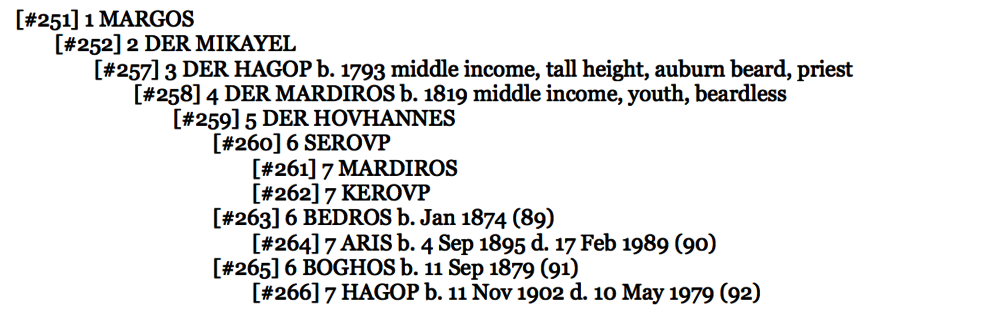

As stated above, [#251] Margos was the brother of [#199] Khachadour/Simon. The three sons of Der Mikayel each formed their own household and followed their father into the priesthood. The Der Pilibosian branch was the smallest of the three. The genealogy wheel indicates they had moved to Bulgaria. It is unclear at what point this occurred. While most likely it was at the end of the 19th or beginning of the 20th century, it could have been prior to the 1840 census. I have not been able to identify the Der Pilibosian family in the census and if not in Bulguria yet, possibly Der Pilibos was serving another community at the time.

Papazian branch

Click HERE to see the Papazian branch.

Including Der Mikayel, the Papazian branch contained 4 generations of priests, thus more than justifying the surname. The Ottoman census listed only one priest in Hazari and it was Der Hagop, apparently his son not yet having been ordained in 1840. Der Mikayel is presumed to have passed away prior to 1840. Thus, it is likely his sons had already divided into separate households, which is born out by the census.

In addition, the Ottoman census data implies that the brothers, [#251] Margos and [#199] Khachadour/Simon, were born prior to 1750. The records from the United States are consistent, the average years per generation was 26.5.

Der Mateosian branch

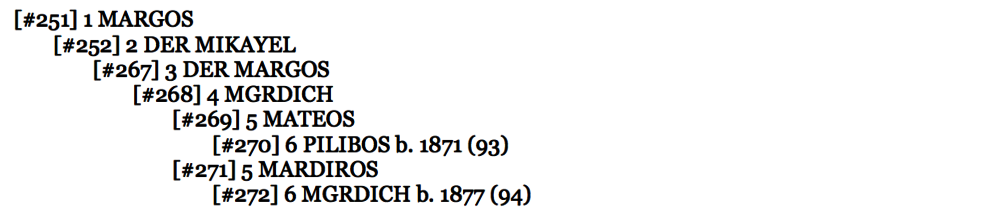

Click HERE to see the Mateosian branch.

The genealogy wheel notes that the Der Mateosian family had moved to the neighboring village of Sisna [now called Varlıkonak], approximately 3 miles to the southwest of Hazari. The Ajemian material on Sisna confirms this. Thus, the move to Sisna may have occurred prior to the recording of the 1840 census. However, I also did not find the family in the census for Sisna.

Khanbegian Wheel

Click HERE to see the Khanbegian wheel.

Khanbegian branch

The Khanbegian family was extensive. In the 1840 census, there were two separate households, one headed by [#274] Bedros and the other by his oldest son, [#275] Movses. The census indicated Bedros’ father was named Sarkis while the genealogy wheel states Mardiros. Other than that, the census and genealogy wheel are in agreement. Considering [#274] Bedros was born in 1768, his father, the patriarch of this clan, was most probably born prior to 1750. Though the 10-year span between the births of Movses and Bedros is unlikely, thus Bedros could have been born even earlier.

There are questions regarding the portion of the genealogy wheel relating to [#316] Avak. On 18 Jan 1921, the SS Belvedere arrived in New York city with two passengers, Mariam and Boghos Khanbegian, joining Avak. The ship manifest indicated that Mariam was Avak’s daughter-in-law and Boghos was his grandson. The genealogy wheel stated Avak had no male offspring. Avak’s wife was named Mariam and from 1921 through 1927, she was listed as living with him in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It seems likely that the Mariam on the SS Belvedere was Avak’s wife instead of daughter-in-law. The unanswered question then becomes who was Boghos?

The number of years per generation was 33 based on those who immigrated to the United States.

Verdanian/Chngrian/Nersesian/Amirkhanian Wheel

These four families originate from [#332] Mardiros and his two sons, Khachadour and Manoug. Based on the available information, Mardiros must have lived during the first half of the 18th century.

Click HERE to see the Verdanian/Chngrian/Nersesian/Amirkhanian wheel.

Verdanian branch

Click HERE to see the Verdanian branch.

There are a number of discrepancies in names, but enough agreement to confirm the Verdanian household in the 1840 Ottoman census. The two sons of [#334] Krikor were living in the same household. In the census, the sons are listed as Mardiros and Ghazar but on the genealogy wheel they are listed as Hovhannes and Babo. The genealogy wheel lists Mardiros as one of the sons of Hovhannes. The tree above adheres to the census, although other interpretations are equally likely. Thus, [#340] Mardiros, not Hovhannes, is presented as the son of Krikor.

[#335] Ghazar was shown to have a son named Ohan in the census. The genealogy wheel does not include Ohan. I have presented Ohan as a fourth son that might have passed away as a child, but it could also be that Ohan was the name of one of the other sons. The genealogy wheel indicates the descendants of [#335] Ghazar/Babo moved to Bulgaria in 1878.

The census also included a son named Avak to [#340] Mardiros which I have assumed was the same person as [#344] Hovagim from the genealogy wheel.

The records of the United States indicate that the number of years per generation was high (34) for this family, though the sample size is very small and the results skewed by [#353] Ghazaros (56 years) and [#359] Serop (47 years).

Descendents of [#358] Movses went by Movsesian.

Chngrian branch

Click HERE to see the Chngrian branch.

According to the genealogy wheel, the Chngrian branch originates from a son of [#333] Khachadour. The name of the son appears to be Serop. However, in the Ottoman census the head of the household was [#366] Khachadour, son of Krikor. Also living in the house was his paternal uncle, [#364] Hovhannes, son of Mgrdich. Problematically, [#333] Khachadour had a son [#334] Krikor that was the head of the Verdanian branch, as already noted above. Thus, it is extremely unlikely that he would have another son Krikor. In addition, if Hovhannes was a paternal uncle of [#366] Khachadour, then Mgrdich would be a brother of [#333] Khachadour. Mgrdich is not mentioned in the genealogy wheel. While speculative, I have presented Krikor and Serop as the same person while listing Mgrdich as a brother.

The remainder of the tree is consistent between the genealogy wheel and Ottoman census. In addition, the number of years per generation from U.S. records was a reasonable 30.

Nersesian branch

Click HERE to see the Nersesian branch.

The genealogy wheel and 1840 Ottoman census are in agreement for the Nersesian clan. This branch descends from [#391] Sahag, another son of [#333] Khachadour. While Sahag was not alive in the 1840 Ottoman census, his son Nerses (presumably the source for the surname) was listed as 57 years old.

The average years per generation based on the United States records was high at 37 years. One possible explanation is that the year of birth for [#393] Manoug in the Ottoman census should have been later than 1814.

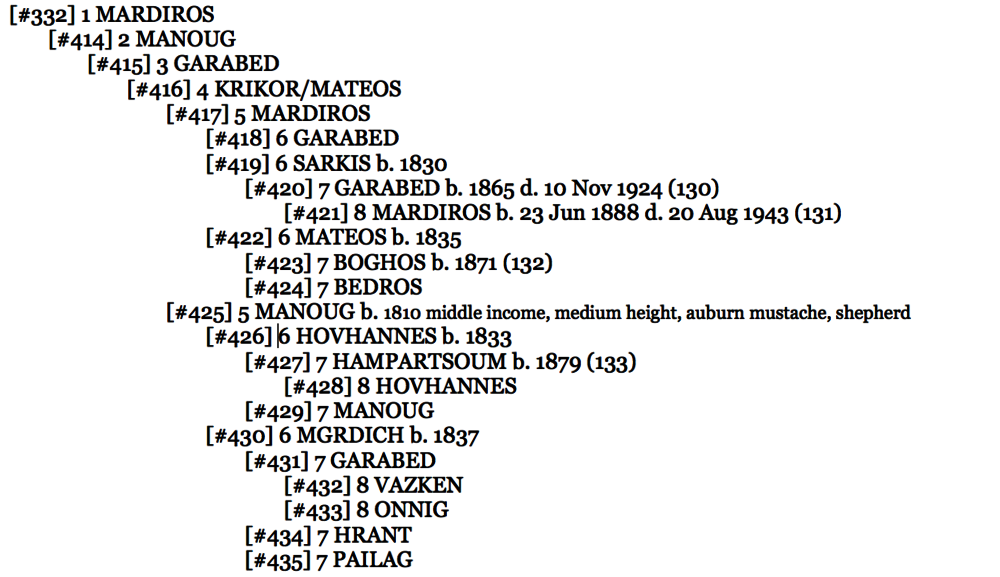

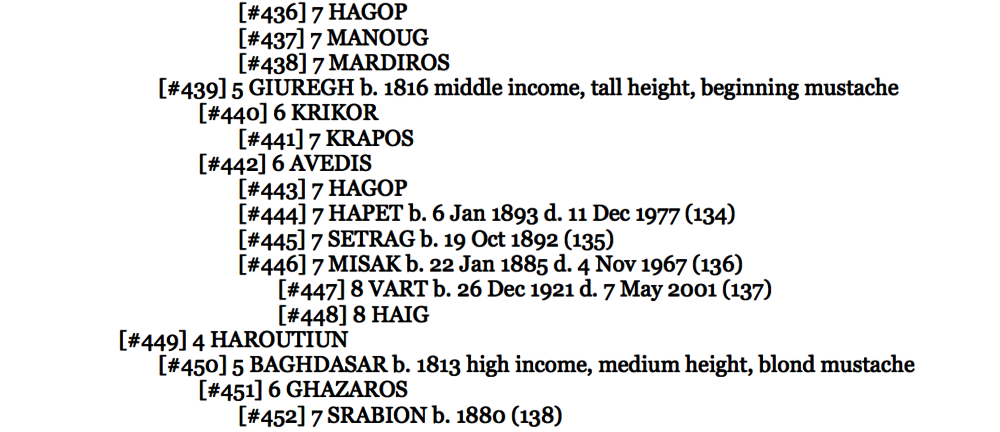

Amirkhanian branch

Click HERE to see the Amirkhanian branch.

The genealogy wheel and Ottoman census are almost in complete agreement. The genealogy wheel indicated there were two sons of [#415] Garabed named Haroutiun and Mateos. However, the 1840 Ottoman census implies only one son named Krikor. I have retained the genealogy wheel’s treatment of [#450] Baghdasar as a son of Haroutiun. I have also assumed that Krikor from the census is the same as Mateos from the genealogy wheel.

The average years per generation based on the United States records was rather high at 36 years.

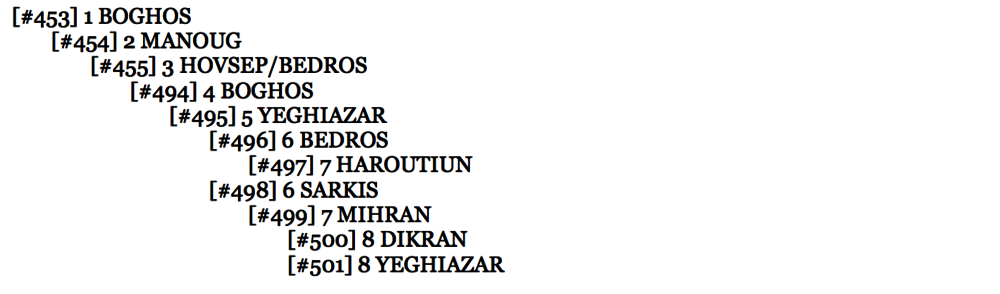

Tatian/Mihranian/Hovnanian/Tashjian Wheel

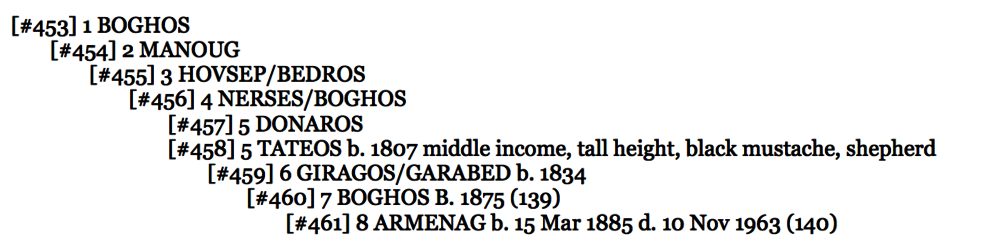

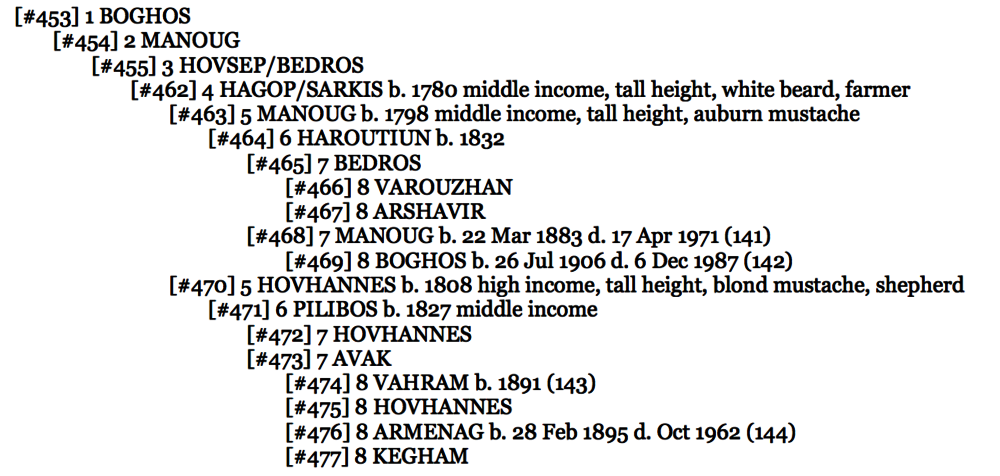

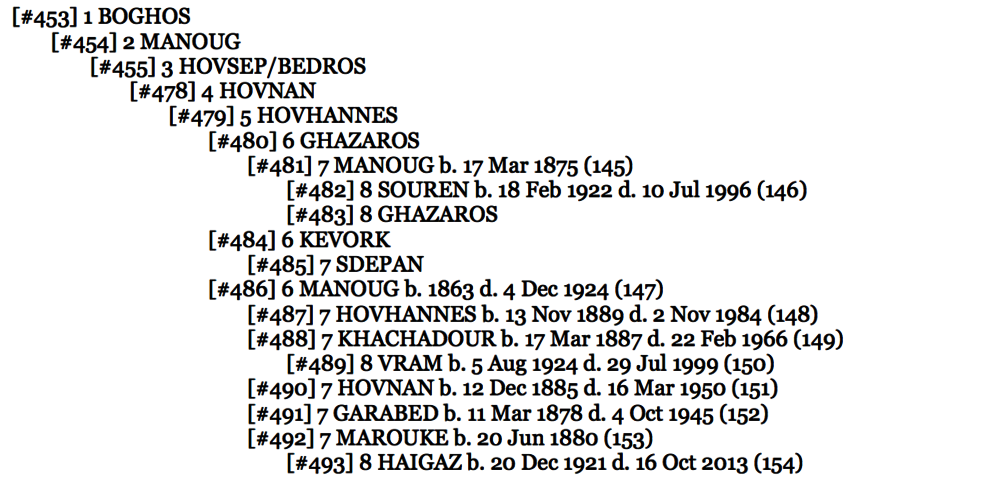

These four families originate from [#453] Boghos, his son [#454] Manoug and grandson [#455] Hovsep/Bedros.

Click HERE to see the Tatian/Mihranian/Hovnanian/Tashjian wheel.

Tatian branch

Click HERE to see the Tatian branch.

I was unable to identify with certainty the Tatian family in the Ottoman census. I have included information based on the head of household named Tateos. However, there are differences from the genealogy wheel. The Ottoman census listed Tateos’ father as Nerses where as the genealogy wheel stated the name as Boghos. In addition, Tateos’ son was identified as Giragos in the census while the genealogy wheel stated the name as Garabed.

The year of birth for [#461] Armenag is questionable. If his father Boghos was indeed born around 1875 as U.S. records indicate, then Armenag could not have been born in 1885. Upon arrival to the United States, he stated his age as 21 in 1920 which would make his year of birth a more reasonable 1899. According to the 1940 U.S. census, he was 52 years old, making his year of birth approximately 1888. However, Armenag’s World War II draft registration and death certificate state he was born in 1885. I have shown the year as 1885 although it was likely that either Armenag was born later or his father was born earlier. Including both Boghos and Armenag, the average years per generation was 26 years.

Mihranian branch

Click HERE to see the Mihranian branch.

It is unclear why this branch of the family went by Mihranian as there does not appear to be any ancestor named Mihran. [#473] Avak possibly spent time in the United States prior to 1910, but had returned to Hazari by the time his son, [#474] Vahram, arrived in 1909.

The genealogy wheel stated the father of [#463] Manoug and [#470] Hovhannes was named Sarkis, yet he was alive at the time of the 1840 Ottoman census and his name was given as Hagop. In addition, Hagop’s father was named Hovsep according to the census while the genealogy wheel instead stated Bedros. The sources are in agreement for the remainder of the tree.

[#468] Manoug could well have been born up to a decade earlier as some records indicate. However, I left the year of birth at 1883 per Manoug’s naturalization papers and World War II draft registration. The average years per generation was 34 years.

Hovnanian branch

Click HERE to see the Hovananian branch.

Clearly, [#478] Hovnan is the source of the surname. I could not identify the family in the 1840 Ottoman census. Household #9 is the most likely one, but the differences are too great to be definitive. However, many of the men immigrated to the United States. [#487] Hovhannes had a son named Khazhag that was born in Massachusetts on 16 Jun 1924. It is unclear why he was not included on the genealogy wheel. In addition, on the genealogy wheel [#489] Vram was shown as the son of [#490] Hovnan, yet census records make it clear Vram was the son of [#488] Khachadour. Similarly, the genealogy wheel displays [#493] Haigaz as the son of [#491] Garabed whereas he should be listed as the son of [#492] Marouke. In 1937, Marouke would have another son named Hovsep.

The years of birth are consistent with what is known from the portions of genealogy wheel related to the Mihranian branch.

On 1 February 1919, Avak Kupelian arrived at the port of Seattle Washington on the SS Kashima Maru sailing from Yokohama. Traveling with Avak were his wife, Nazeli, and sons, Markar and Souren. He had been born in 1884 in Chmshgadzak and traveled the long path from there through Russia before arriving in the United States. In the 24 May 1919 issue of the periodical Gotchnag, Avak detailed a list of those from Chmshgadzak that, like him, had passed to Russia following the retreat from Erzurum in 1917. The list of those from Hazari is interesting in the context of the genealogy wheels. For the purpose of this article though, I simple repeat the information as presented.

Heybatian - Mardiros, wife, children, brother, Marta, Antranig

Antreasian - Aghajan, Taniel, Vahan, Satenig, child, Vahan's wife, Aleksan's son

Parounagian - Dikran, child, wife, Brother's wife Marta

Atamian - Adom, child, wife, sister

Soghigian - Partogh, wife, Dikran, wife

Amirkhanian - Hampartsoum, child, wife

Not Stated - Antranig, wife, mother-in-law

Tashjian branch

Click HERE to see the Tashjian branch.

I could not identify the Tashjian household in the Ottoman census nor could I find any records for the family in the United States. The genealogy wheel stated [#497] Haroutiun had moved to Smyrna [Izmir] in 1898.