Malatya - Holidays

Author: Sonia Tashjian, 08/07/2022 (Last modified: 08/07/2022) - Translator: Maral Aktokmakyan

From ancient times the people of Malatya have always been passionate to celebrate the church feasts and folk holidays properly, as well as to respect all the rules of the ethnic community, which have traditionally been passed down from generation to generation. For Saturday evening service, they stop work and go to church. Likewise on Sundays, young and old rush to church to attend the Liturgy. Here, they do not forget their financial obligations. They warmly kiss the icons, as well as take the Holy Communion. Afterwards, they spend their time with their family and relatives. This gathering takes place indoors, or if the weather is favorable, they organize field trips to nearby fields and gardens. [1]

New Year

The last days of the year and the first days of the coming year are called gakhoug, which means hanging. Little boys, each holding a cloth bag, walk from house-to-house shouting, “Give me my gakhoug.” They throw their bags inside the open doors or hang them down the chimneys. The landlords, who are already gathered around the festive tables with their families, fill the bags with dried fruit, fruits, nuts, gata, and sweets. The boys go back home happily to enjoy their treats. On the first day of the year, they need to go to bed early so that the entire year goes just as happily. Otherwise, the evil spirit (shvod, the mythical evil) comes and takes them away and drowns them in deep waters.

The traditional, festive food of that day is perperabour, purslane soup. It is prepared with dried purslane and different grains sown in springtime. According to an ancient custom, after cooking the meal, the housewife would take out the giserets (half-burned) wood left in the hearth in order to use them to light the hearth again on Christmas eve. It is also customary on that evening for the housewife to place a large stump of wood in the hearth, so that it will stay lit until dawn, and keep the firewood burning, believing that the light and warmth of the house will hence last the entire year.

According to the belief, young people would secretly go to the spring in order to be able to capture the magical moment when silver will flow from the spring water. In the morning, everyone rushes to the church. On the way home, they begin to congratulate each other, lavishing good wishes to one another. But the real congratulatory visits start in the evening. Families with a bride go to their in-laws' houses with gifts in large baskets filled with fruits and presents in other parcels. In accordance with an unwritten rule, the in-law must return the basket by filling it with even more fruits. [2]

Malatya, circa 1900. The Saint Krikor Lousavorich (Gregory the Illuminator) Monastery. The children photographed standing outside the building are Armenian orphans who were residing in the monastery’s orphanage at the time (Source: Bab-Oukhdi periodical, year 1, September, number 3, 1935, Cleveland, Ohio).

Holy Christmas and Baptism

This holiday has a special significance in Malatya. On Christmas Eve, everyone, young and old, goes to church with devotion, to repent and receive the Holy Sacrament before the end of the fasting period. The donation of that day is called khachi krvadzk, the "writing of the cross". The greatest donor will be given the privilege of becoming the godfather for the following day’s Holy Baptism.

After performing the baptismal rite, the believers approach to kiss the Cross and Gospel, while each drinking a spoonful of blessed water and making a donation. The rest of the water is taken to the priest's house, from where those who wish can go and take some.

The following day is dnorhnek, the blessing of the home. The priest makes his rounds from house to house to perform the blessing of the home ceremony. The housewife would have placed a plate full of cereals/grains (wheat), a loaf of bread, salt, water, yeast, her husband’s purse, as well as something symbolizing his job. At the end, they kiss the cross and reward the parish priest.

These visits of blessings continue for a few more days. [3]

St. Sarkis

On the Wednesday preceding this holiday, when the fast of Arachavorats Bahk (Catechumen, also called the First Lent) begins, the people of Malatya have a special custom. A few strands of hair are cut from each member of the family, repeating, ”St. Sarkis, a strong bastion, hold my rein, to not lose my soul." According to the belief, on that day the mane of St. Sarkis the general’s horse was cut short. On this occasion, the ritual of pulling each other's hair in the family is called, esh gndoum, donkey grooming. And on the day of the feast, after the church liturgy, the in-laws, loaded with gifts and sweets, go to the bride’s house. The bride, who has been fasting for four days, is especially commendable, and hence she receives valuable gifts. [4]

Candlemas Day

The feast of Trndez, Candlemas Day (February 13) is also called Molorod. In Malatya, the same day is also known as Melet or Melemet Day.

An evening service is held in the church, and families and their children attend the ceremony.

The newborns are brought to the church to end the child’s forty-day seclusion. The mothers-in-law throw basdegh (fruit leather) on their sons-in-law from the upper gallery. Burning candles are taken from the church with which to light candles in their houses.

In the old days, a candle was brought from the church to light a fire in the yards to have fun, to jump on it, and to sing together. Later, however, this order changed, and people began to tear off the paper that covered their windows (used instead of glass) and burn it on the roofs of their houses. In this way, this custom becomes a ritual of burning evil and, of course, a convenient opportunity to repair the papers on the windows in the houses.

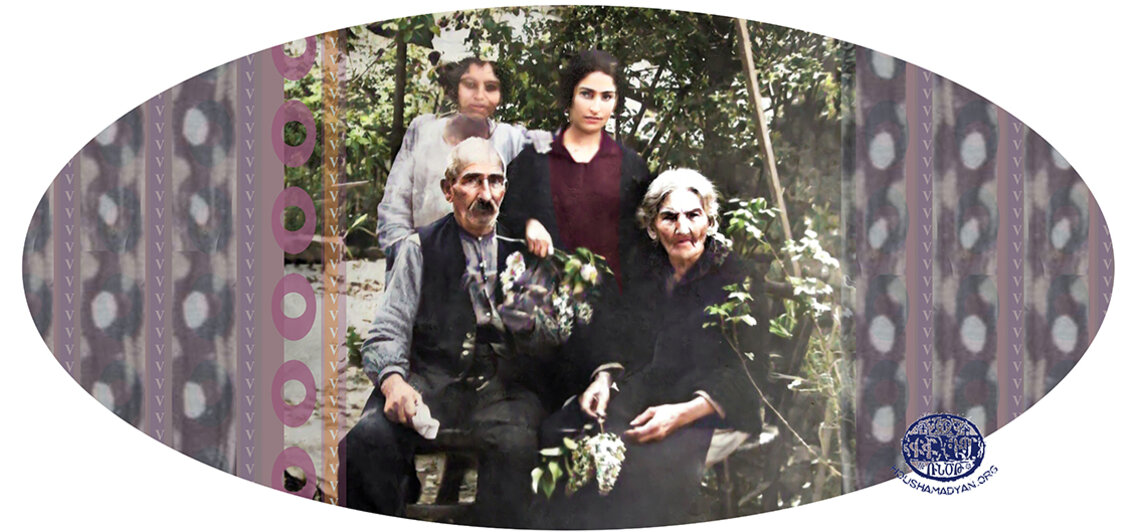

1) Malatya. Members of the Mokkosian, Kouyoumdjian, and Mardigian families (Source: Aras Printing House, Istanbul).

2) Aleppo, 1940. Actresses involved in a production of the Anoush opera organized by the Malatya Compatriotic Union. The performers were natives of Malatya (Source: Bab-Oukhdi periodical, year 7, December 1940, number 1 (25), Cleveland, Ohio).

Carnival

Like many church holidays, the date of Carnival is also flexible and linked with the lunar calendar. The Resurrection Day of that year is determined by the church calendar, which is preceded by Great Lent and the Carnival days. Carnival is associated with the beginning of the springtime, the awakening of nature, as it is the memory of a dying and rising divinity. Consequently, it is celebrated in February, and sometimes in early March. The people call it a Paregentan, which literally means “good life.”

There is no limit to the joy of the life-loving people of Malatya on this holiday. According to the belief, St. Sarkis, who had already found grooms for the young girls who fasted and appealed to him, climbed to the top of a hill called Kaka on a (gray) horse and gave fifteen days of joy to the people before the start of Great Lent.

Monday, Wednesday and Friday of the first week of Carnival are called “kel” and the heroic Battle of Vardanants is commemorated in the church. [6] Each family allows a domestic animal to be slaughtered, to the extent of their capacity, to prepare a variety of meat dishes. The lyrics of the folk songs mention the roasted mutton prepared that day, the red, strong wine filled in porcelain glasses, the delicious appetizers, as well as the festivity of the invited musicians and the feast. [7]

People, young and old, men and women, rich and poor, ordinary citizens and officials, flock to parks, gardens, backyards, rooftops, and squares to celebrate this holiday, which symbolizes good living. Until the first day of Lent, the people sing, dance, eat, drink and play. [8]

Lent (Bahk)

On the first day of Lent, the adults rush to church, while the young brides and girls clean the houses thoroughly and wash all the dishes so that no leftover cooking oil remains. Turkish and Kurdish retailers [Tur. çerçi] roam in the Armenian neighborhoods and offer manna, boiled beets, thyme, anise to be exchanged for food. They call the transition from oudik, ‘meat day’ to Lent, pernapokh, ‘variation in food.’ The first Monday of Lent is called paglakhoum, bean-eating. On that day they prepare a dish with beans. It is also called mgndon, holiday of the mouse. In the cellar of the house, a salad is filled inside the holes opened by mice, so that they can have a feast and not chew off the clothes of the house folks. It is also customary to make lovig, bean soup or ttvok kufta, bitter meatball on that day. [9]

As is customary, everyone fasts (bahk) either by abstaining from eating meat and other animal products, or fasts (dzom) with total abstinence, especially on Wednesdays and Fridays. Young girls offer their prayers by fasting so that they can be lucky and receive a marriage proposal. Neighbors, friends and acquaintances prepare special meals and visit the girls to encourage them. A mother-in-law gives a gold ornament to the engaged girl as a present. [10]

On Saturdays during the period of Lent, they do not go to the bathhouse, they do not do laundry, nor do they bake bread. It is customary for the wealthy to distribute food and fruit to the poor, to donate to the church (incense, candles, clothes, etc.), asking the saints to intercede for their children, especially for their sons who are away from their homelands or daughters who are of the age to get married. [11]

On the second Sunday of Lent, it is customary to boil hadig, grain, which is also called goulepa ofSt. Toros. It is considered to bring luck if one gets the opportunity to taste that day’s hadig in seven different houses. [12]

Throughout the fast, the fervent people of Malatya make a pilgrimage to nearby or distant holy places.

Midlent (Michink)

The day that marks the halfway point through the Lenten period is called Michink, Midlent, and it coincides on a Wednesday. The special dish of this day is called mchok kufte, mid-lent meatball. They put a coin in one of the meatballs, with the intention to be found by a lucky person. They go to church in the morning to participate in the church service. Families who will soon have brides (harsntsou) visit their in-laws (khnami), to gift their future daughters-in-law clothes, along with trays full of sweets and boiled grains. Fasting brides-to-be are especially respected and admired. [13]

Palm Sunday

On Palm Sunday, little boys make wreaths and bouquets of fresh willow twigs, bring them to church, and preach: "Easter is near, Zarzartar has blossomed, all the bald heads reeked.” After the Liturgy, people take those blessed branches with them to their homes.

Holy Week

On Wednesdays, tarhana is cooked without oil and plant it on the walls of the house right before eating it in order to prevent scorpions from entering the house.

Thursday is deemed a grave sin. Church bells are heard regularly throughout the day, and worship is held throughout the day. Everyone works until noon, then goes to church to attend services that last until late at night. Some people receive communion that day and end their fasting.

For the vodnlva, Pedilavium, the ceremony of the bathing of the feet, believers donate a portion of the cooking oil they use in their houses to the church. At the end, they take the blessed oil in a small bowl with them to mix with the oil in their house, and in this way the oil and the goods of the house get blessed. They also anoint the diseased body parts with blessed oil, believing in its healing power.

The meal of that day is keshkek, harissa of the fasting period, which is cooked by mixing chickpeas and vegetables. When they taste it, they sprinkle red hot peppers on it, which is for the commemoration of the sufferings of Christ.

In the evening, everyone goes to church to attend the night service and pray in mourning.

Fasting on Friday is forbidden, for spite of Judas and Satan. According to an old belief, carpenters would pound nails to nail Judas’s eye. [14]

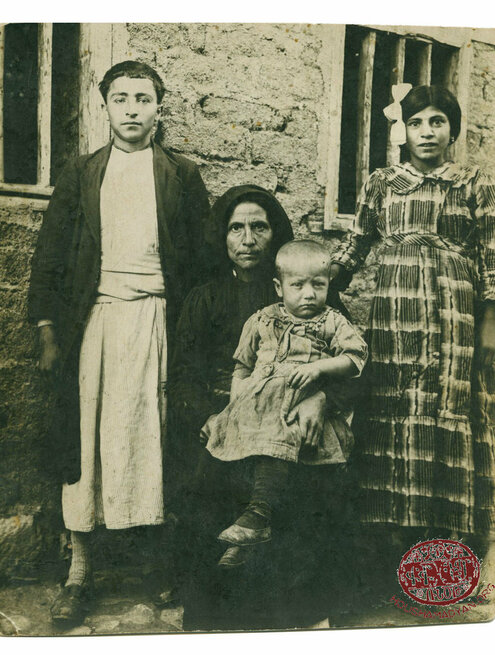

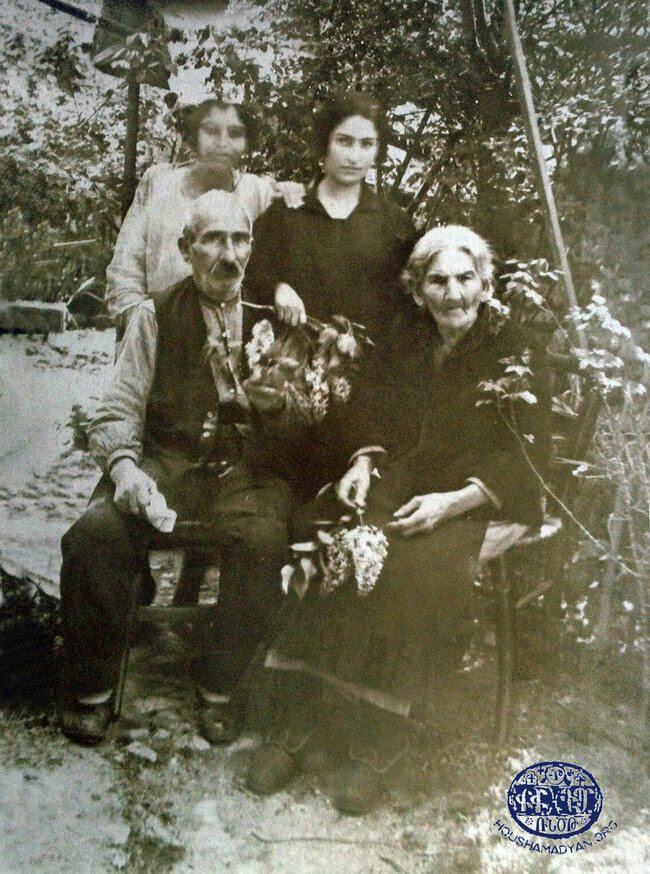

Malatya. The Kalousdian family, ca. 1910-1911.

Seated, from left: Kerop Kalousdian, Kalousd Kalousdian, their mother (name unknown), Serop Kalousdian. Kerop, Kalousd and Serop are brothers. Front row (from right): Mari (later Uluhudjian), (unknown child), and Satenig (later Gulhandjian). The other children in the front row are Serop's and Kalousd's children (name unknown). Back row (from left): Pepron Kalousdian (Kerop's wife), the name of the child being held by Pepron is unknown, Khatoun (Kalousd's wife, nee Motian), an unknown woman, Margarit’s sister (name unknown), Margarit (Serop’s wife), Taniel (wearing a fez), Sarkis (wearing a fez) (Source: Roupen Kulhandjian collection, Beirut).

Easter (Zadig)

On the eve of Easter, the community attends the liturgy, then they taste djadjekh (tzatziki) with beets. According to another ancient custom, some people break their fast on that day, prepare a memorial meal, hokegeragour, for the occasion and invite the churchgoers to their home upon their return from the church, and they take some of it to the homes of the poor. This custom is called " Կէրէկմութ", meaning the Sunday meal.

It is customary in Malatya to have new clothes for Easter. Before going to church, adolescents and young people, all dressed in festive clothes, kiss the hands of grandparents to show their respect. The latter bless them by repeating: “Live long and grow up, may you live this day every year, my child.” Each believer prepares his savings for the day’s offering. When they approach the altar of the church to kiss the cross, they place their share in the church treasury, buy incense and candles, and give a monetary gift to the charity organization for the poor standing in front of the church. [15]

After the liturgy, children and adolescents enjoy havgtakhagh, egg cracking game. The young first go and congratulate the adults, then visit each other’s houses. Grandmothers would have baked Easter red, sweetbread to pass out to everyone that day. Like Christmas, on Easter day as well, parishioners go from house to house for blessings. [16]

The next Sunday is a day of pilgrimage to the holy sites. They dutifully go and visit with their families to make sacrifice offerings. [17]

A copper tray crafted in Malatya between 1900 and 1910. It belonged to the Vorperian family. It has a diameter of 95 centimeters (37 inch) and a depth of 3 centimeters (1,18 inch). What makes the tray unique is the Vorperian family tree that has been engraved onto its surface. The family tree contains the names of 216 individuals. After the Genocide, this tray remained with the surviving members of the family who continued living in Malatya. In the 1960s, it was sent to family members living in Soviet Armenia, where it is still kept today.

All Souls’ Day (Merelots)

The Monday following the Feast of Tabernacles is All Souls’ Day, which is celebrated in Malatya with special splendor. They offer up sacrifice and distribute them to the neighbors and the poor. They go to the cemetery to bless the graves of their dead. The cemetery gets crowded with people up until nighttime. They are there with all the family members, therefore it is one of the best opportunities for young people to meet and fall in love. The little ones run around the nearby fields to pick flowers and make whistles with willow branches. After the requiem service, prayers are said on the graves, incense and candles are lit. Then they set a table over the tablecloth on the ground and men drink oghormatas, that is a glass of wine, for the souls of their dead.

Thus, the whole cemetery is filled with burning incense and candles, loud cries and mourning, as well as toasts with good wishes. In the evening, the rest of the food is left on the tombstones for the beggars, the crumbs of which go to the birds flying in the sky and the animals in the fields. [18]

Ascension Day (Hampartsoum)

Forty days after Easter, the Armenian Church celebrates the Feast of the Ascension of Christ. It is usually performed in the flowering month of May, on a Thursday.

On the eve of the holiday, on Wednesday morning, little boys and girls gather bouquets of various flowers from the fields upon the advice of their grandmother. During this time, young maidens bring water from seven different springs to mix them all in a ritual jug, which later, they fill with wildflowers. Then they visit the houses of the neighbors and announce the good tidings: “Bride, we will draw lots in our house, give us something to take ․․․.” This way, small items such as knives, scissors, keys, jewelry are collected from the houses and placed in the vessel. The vessel, full of these items, water and flowers, is kept on the roof at night so that the magic of the stars descends upon them.

A special folk song from pre-Christian times about the feast describes the process of preparing the ritual, where it is mentioned that the cross of the house is placed in a vase full of flowers, so that the ritual is blessed, and divination can be fulfilled. [19]

The next day, the women and young girls, who had sent items the day before, gathered after the church service in the yard of the house where the above-mentioned vessel was located. A young girl is placed on a rug spread on the ground, her head is covered with a veil, and a vessel full of flowers is placed in front of her. An elderly woman who has just come back from the church should be the first to pray Voghormya Asvadz, meaning “Lord, have mercy (on us)”. Then, one by one, they start to sing a quatrain and draw an item. This continues until all the items are drawn out from the vessel one by one. [20]

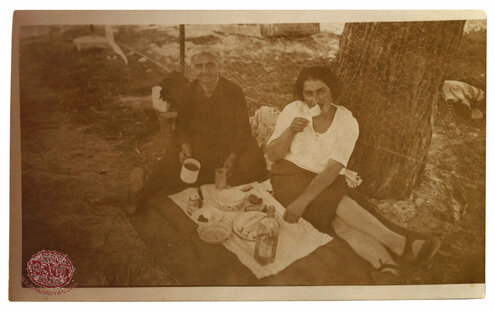

1) Malatya, 1926. Left to right: Manuel Vorperian, Yeghisapet Vorperian (seated), and Khatoun Vorperian. The child sitting on Yeghisapet’s lap is her grandchild. Yeghisapet’s husband, Senekerim, was killed during the Genocide (Source: Vorperian Family Collection, Yerevan).

2) Malatya. Maryam Ansourlian’s children. Their names are unknown (Source: Vorperian Family Collection, Yerevan).

Transfiguration of Jesus Christ (Vartavar)

After the conversion of Christianity by the Armenians, this pagan holiday of the summer solstice on June 21, began to coincide with the Feast of the Transfiguration of Christ in the Armenian church calendar. Hence, it became one of the five holy days of the Armenian Church. Vartavar is celebrated forty days after the Feast of the Ascension.

Given that there are many springs and fountains in the city of Malatya, this ancient festival dedicated to the worship of water is celebrated in the backyards of houses, unlike other areas where people go out to the fields on the shores of springs, rivers or lakes. According to local tradition, Noah descended from the ark and sprinkled water on his family members so that they would not forget the Creator's omnipotent power and the punishment of the destruction of the world, that is, the flood. To commemorate the story of Noah’s Ark, it is customary to fly a dove for the occasion of the feast.

Immediately after the liturgy, the enjoyable water games begin, in which men and women of all ages take part. Adults throw water on passers-by from the rooftops where they stand with bowls or buckets full of water. The teenagers, running one after the other, pour water with buckets on each other. The young people joyously try to throw each other into a spring nearby. Once everyone is soaked, they walk to a nearby lake or river and immerse completely in the water.

The traditional meal of the day is stew, which is a meal cooked with vegetables, but meat is also added on this holiday. [21]

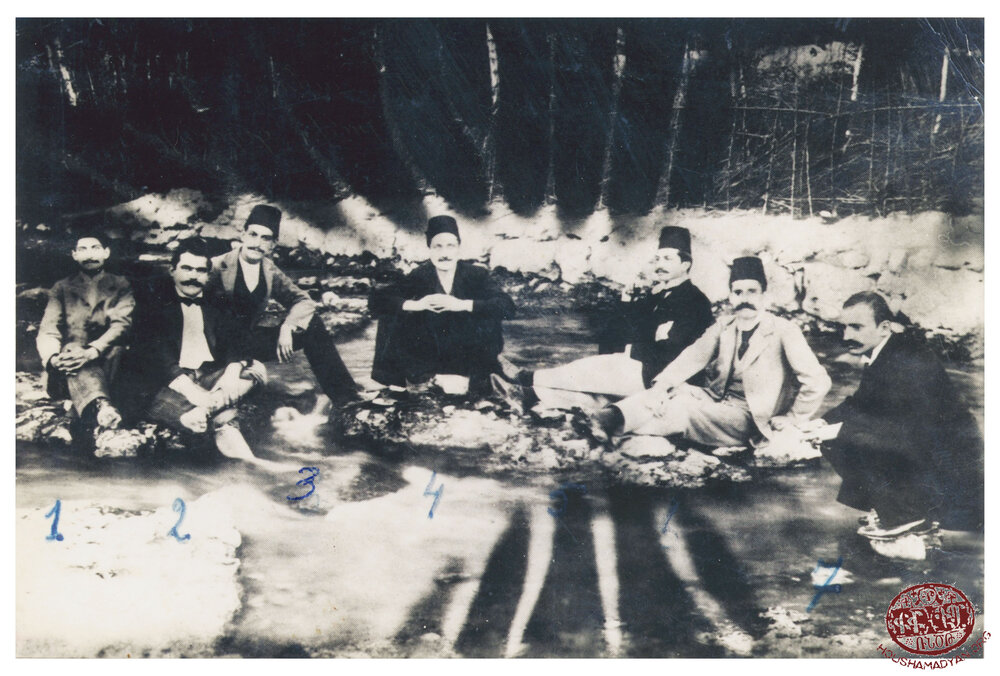

Malatya, circa 1900. A group of Armenians on the bank of the Bab-Oukhd River. Left to right: Haroutyun Lekerdjian, Khosrov Sarafian, Setrag Moumdjian (killed in 1915), Kapriel Ansourlian (killed in 1915), Khachadour Bonapartian, Professor Mgrdich Vorperian (killed in 1915), and Professor Samuel Khachadourian (Source: Vorperian Family Collection, Yerevan).

Blessing of the Grapes

The next feast day is the Day of the Transfiguration of the Virgin. It is also commonly known as the blessing of the grapes. According to the church calendar, it is celebrated on the 15th of August coinciding with the closest Sunday. Some associate this feast with the pagan Navasart festival, which was celebrated with great splendor and during which the ritual of thanksgiving for the harvest was performed. In time, the harvest festival turned into grape festival. By blessing the grapes, the church blesses all the crops and goodness.

Malatya is famous for its abundance and rich varieties of grapes. Therefore, this particular feast-day, which is dedicated to the blessing of the grapes is also celebrated with grandeur. In the morning, people pick the best bunches from their gardens and take them to the church as a donation, so that their gardens and crops would thus be blessed. At the end of the liturgy, the priest performs a blessing ceremony, and the grapes are distributed to the believers. The meal of this feast day is eggplant with meatballs.

Exaltation of the Holy Cross

The last of the feast days of the Armenian Church is the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, in memory of the liberation of the Cross of Christ. During this feast day in Malatya, the entire family makes pilgrimages to distant and nearby shrines. They organize festivities, sacrifice offerings, and receptions. The main food of the day is harissa.

Pilgrimages

Pilgrimages fulfilled on the occasion of the holy days have an important place in the life of the people of Malatya. Since ancient times it has been a sacred custom, as well as a belief, to make a vow on various occasions and to make a pilgrimage. People, whether adults, children, pregnant women, or the sick, mostly walk while some travel on carts on pilgrimages. Women often walk barefoot and murmur prayers all the way. When the pilgrims reach the place of the pilgrimage, they burn incense and candles, kiss the stones and the ground, and then kneel and pray.

According to an ancient custom, adult women hang shreds of cloth torn from their clothes to the trees. And if there is a spring or a fountain at the place of pilgrimage, they take water from it and take it home with them to prepare food with it on special days. The sick often spend several days and nights in the church near the place of pilgrimage.

It is customary to vow to make sacrifices, especially in case of serious illnesses or before travels. Thus, the rooster is slaughtered, boiled, and wrapped in loaves and distributed on the doorstep of the church. The richer family sacrifices a lamb, a goat or a calf and prepares them as madagh, a sacrifice. The meat of the sacrifice is usually distributed with pilaf (rice). On Sundays and holy days, they prepare various meals in their homes, bring them to the church and, after blessing them during the liturgy, distribute them to those who are present. Pilgrims often donate to churches, monasteries, or charity institutions.

If a vow is made to a remote monastery outside the city, the subject invites his relatives, friends, and neighbors to participate in the calling. They go to the monastery in a large group, taking with them the ram to be sacrificed.

There are also rituals of collective vows and sacrifices against the natural disasters that threaten society. The most common are those for rain during droughts, during which sacrifices and rituals are performed.

Pilgrimage to Jerusalem is desirable for everyone. Consequently, many people of Malatya become worthy of the title maqdisi after they make pilgrimage to the site. [22]

- [1] Arshak Alboyajian, History of the Armenians of Malatya, Beirut, 1961, p. 1137.

- [2] Ibid., p. 1138.

- [3] Ibid.

- [4] Ibid., p. 1137.

- [5] Ibid., p. 1139.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] S. M. Dzotsigian, Western Armenian World, New York, 1961, p. 381.

- [8] Alboyajian, History of the Armenians of Malatya, p. 1140.

- [9] Ibid., p. 1072.

- [10] Ibid., p. 1136.

- [11] Ibid., p. 1137.

- [12] Ibid., p. 1106.

- [13] Ibid.

- [14] Ibid., p. 1141.

- [15] Ibid.

- [16] Ibid., p. 1142.

- [17] New Malatia, 4th year, no. 3, page 6.

- [18] Alboyajian, History of the Armenians of Malatya, p. 1143.

- [19] Dzotsigian, Western Armenian World, p. 379.

- [20] Alboyajian, History of the Armenians of Malatya, p. 1143.

- [21] Ibid., p. 1144.

- [22] Ibid.