Anserlian Collection – Los Angeles/Beirut

Author: Sevan Boghos-Der Bedrossian16/06/23 (Last modified 16/06/23) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

This article is based on the family history compiled by Bedros Anserlian. He was the son of Hagop Anserlian and Lousin Anserlian (nee Iskenian), both of whom were born in Ayntab. Over the years, Bedros, with the intention of documenting his family’s history, collected testimonies and biographical information from his relatives, and also investigated church records. Based on this information and research, he published a book on his family’s history, titled Anserlian Dynasty, Los Angeles, 2022.

Bedros’s ancestors hailed from the village of Ansour or Ansir, from which originated the family surname, “Anserlian,” meaning “from Ansour.” Ansour (present-day Buzluk) is located south-west of the city of Malatia, not far from the Euphrates River. According to Bedros Anserlian, the family moved to the city of Ayntab in the 18th century, where they lived until the early 1920s.

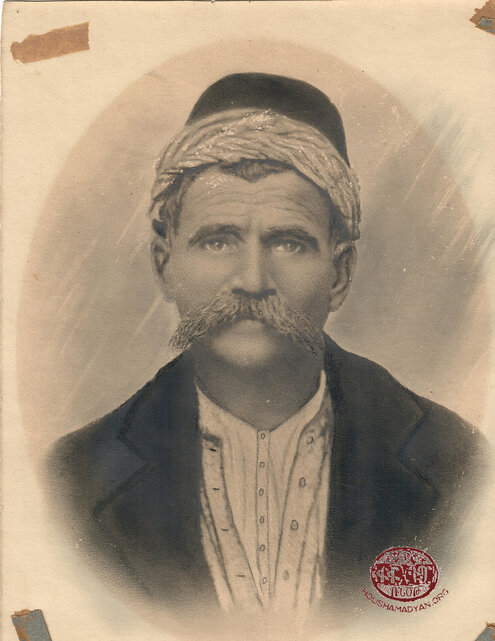

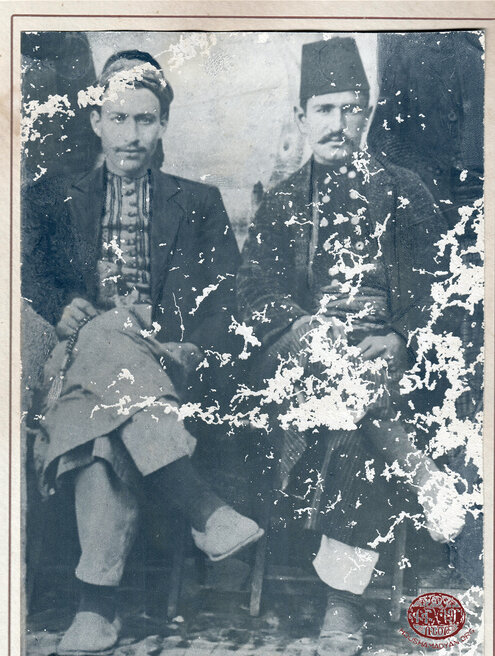

The oldest known ancestor of the family is Movses Anserlian, who was presumably born in the last decade of the 18th century. His descendants included Hadji Avedis Anserlian, who was presumably born between 1840 and 1850; as well as his brothers, Ohannes and Hagop/Yakoub. All three of these men were masons and stonecutters by trade. However, most of their descendants practiced copper smithing or worked as pewterers. As pewterers, they often traveled, for several days at a time, to the cities and towns near Ayntab. They traveled on donkeys. The family’s male children, whenever they reached the age of eight-nine, would be taken in as apprentices by their fathers and learn the family trade. Most of the coppersmiths of Ayntab were Armenian. The city was home to more than 50 copper smithing workshops, each employing four to ten workers. Aside from the Anserlians, other copper smithing families included the Kalemkyarian, Arslanian, Patanian, Guleserian, Knadjian, and Maghakian families.

The Anserlians were best-known for crafting copper kitchen utensils. Many family members were experts in polishing copperware. The items they crafted were exported, by Ayntab-based traders, to Adana, Zeytoun, Malatia, Ourfa, Aleppo, and Damascus.

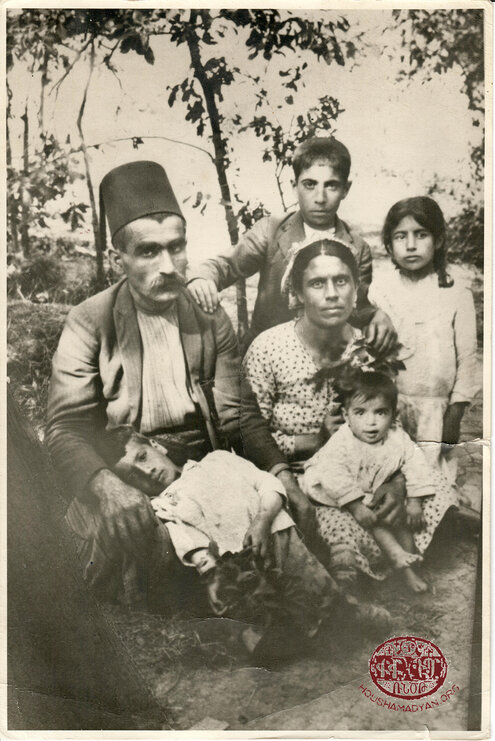

Hadji Avedis Anserlian was married to Anna, and the couple had six children – two sons, Movses and Bedros; and four daughters, Mayrig, Siranoush, Nousia, and Ovsanna. After Anna’s death, Hadji Avedis married Feride, and the couple had two more daughters, Haygouhi and Dikranouhi.

Hadji Avedis’s brother, Ohannes, was married to Sona. In the initial years of their marriage, the couple had no children. Instead, they adopted two boys, Hovhannes and Kevork. Later, Hadji Hovhannes and Sona had three children – two daughters, Mary/Meroum and Arshalouys; and one son, Nazar. Many years later, their adopted son, Kevork, married Mary, his half-sister.

Hadji Avedis’s second brother, Hagop, was a mason, and well-known as a well builder. He was also known as a good singer. He was a member of the acolytes’ choir of the Ayntab church, and also served as the mouazzin of one of the city’s mosques. He had no children, but he had adopted Hagop, his cousin Bedros Anserlian’s son.

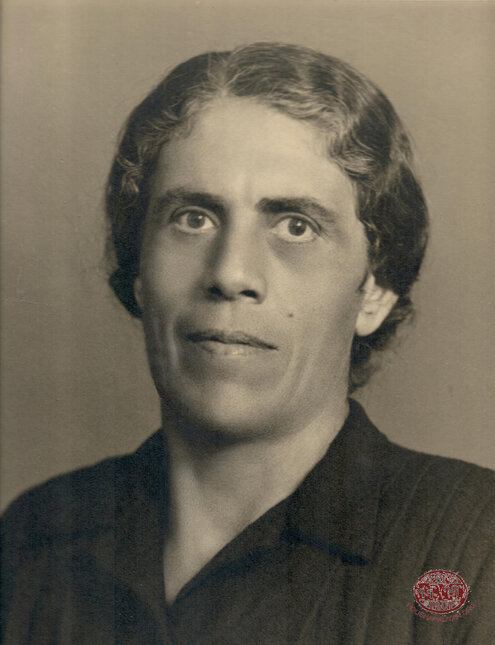

The women of the Anserlian family usually had strong characters. The most memorable among them are Nousia Badji and Mayrig Badji, daughters of Hadji Avedis and Anna; Mary/Meroum, daughter of Hadji Hovhannes and Sona; and Azniv Badji, wife of Bedros, son of Hadji Avedis and Anna. Hadji Avedis and Feride’s daughter, Haygouhi, attended the American College of Ayntab.

Prior to the Genocide, the Anserlians owned homes and stores in Ayntab. They lived on the land they had inherited from their ancestors. In 1915, like most of the Armenians of Ayntab, they were deported. They were marched off in the direction of Aleppo.

The first stage of the journey consisted of a train ride from Ayntab to Aleppo. The Anserlian and the Beynerdjian families, both from Ayntab, were on the same train out of the city. According to family tradition, it was on this train that Bedros (Hadji Avedis and Anna’s son) first met Azniv Beynerdjian. The train was full of deportees. In the midst of this throng, Bedros went down on his hands and knees to allow Azniv to sit and have a chance to look out of the window. They fell in love… Immediately after the years of deportation, when they returned to Ayntab, Bedros and Azniv married.

And so, after the Genocide, the survivors returned to Ayntab, where the local Armenians began a new life after 1919, under French rule. But on April 1, 1920, Turkish forces attacked the Armenian neighborhoods of the city. By then, most French troops had already retreated from Ayntab. The local Armenian population resorted to self-defense, fighting until April 17, 1920, when two French battalions entered the city. This was followed by a short ceasefire. But in late June 1920, armed clashes resumed, this time between French and Turkish forces. The fighting continued until February 9, 1921, when the Turkish forces in Ayntab surrendered to the French, and the city’s residents resumed their lives. In mid-1921, French forces left Ayntab. This precipitated a mass exodus of the local Armenians, which had already begun during the armed clashes. Throughout 1920 and 1921, members of the Anserlian family left Ayntab and settled down in Aleppo.

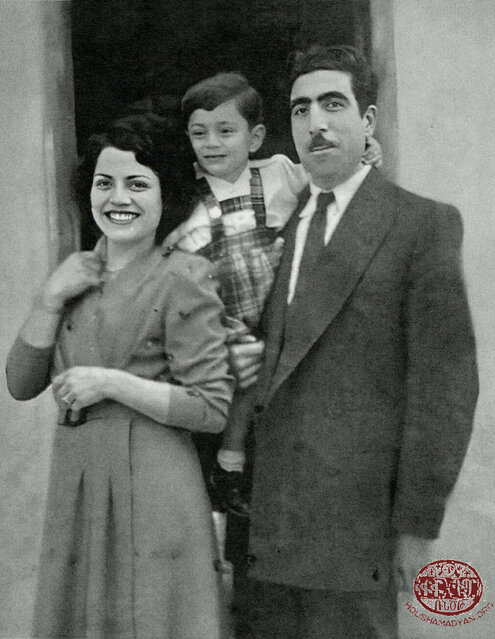

During the battles for the self-defense of Ayntab, the home of the newlyweds Bedros and Azniv was shelled and destroyed. They escaped and hid with another local family, but their son, Hagop, was left under the ruins. He was thought to have perished. But on the following day, when the family returned to the ruins, they heard Hagop’s cries, and rescued him. He had survived thanks to a piece of Turkish delight, wrapped in cloth and hanging from his neck. In those days of famine, Turkish delight was used to provide additional sustenance for babies, as well to satisfy their instinct to suckle. This little Hagop was the father of Bedros, the source of the information presented in this article.

In Aleppo, the Anserlian family settled down in the Dawoudiyeh neighborhood. They lived in a one-room home, which, in the initial stages, had a tin-and-cardboard roof. Azniv and Hagop had four children: Hagop, Alice, George, and Apraham. In this new city, the Anserlian men once again began shining in their chosen field, namely copper smithing. Their workshops were located in the same neighborhood, in the city’s copper market (Djidedyai Ghazanchi Charghus or Souk al Nahas). Uncles, brothers, and cousins worked together, side-by-side.

In Aleppo, after finishing their education, many members of the Anserlian family specialized in various occupations and crafts. They worked as educators, civil servants, jewelers, electricians, machinists, and naturally, coppersmiths.

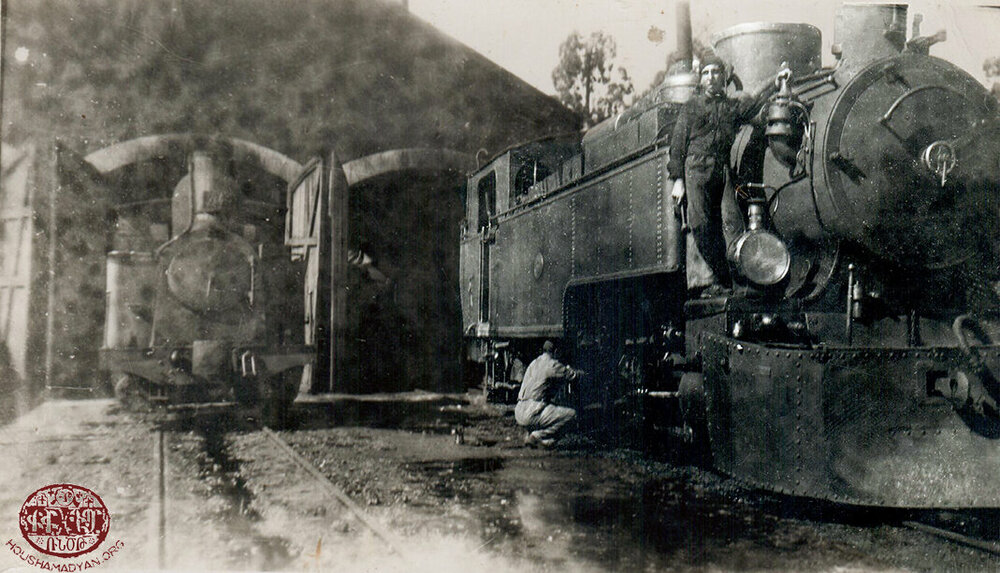

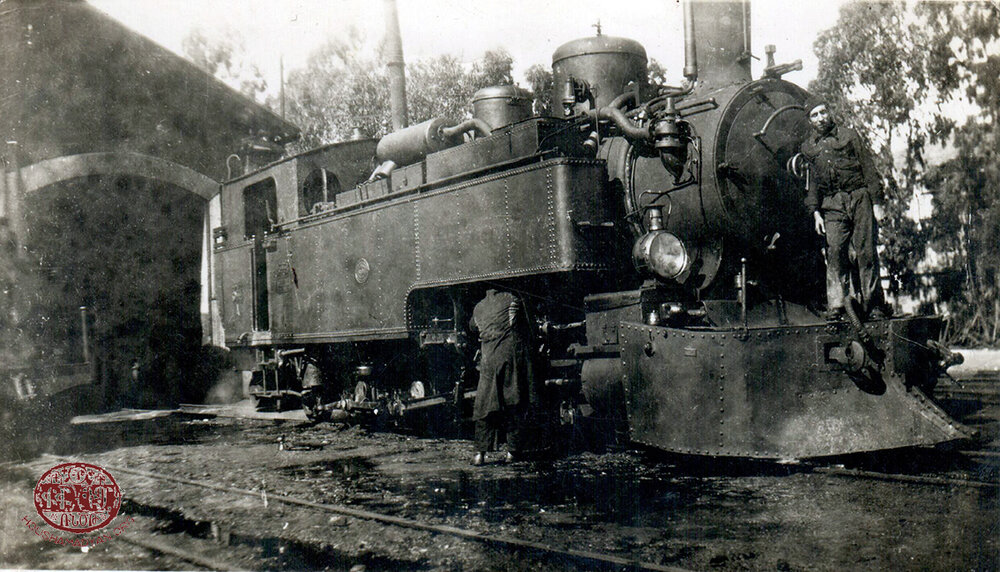

Aleppo would not be the family’s final stop. Anserlians traveled on to Jerusalem, Beirut, Amman, and Kuwait. In Beirut, Avedis Balabanian (Siranoush Anserlian-Balabanian’s youngest son) founded a workshop that made metal closets. The brothers Avedis, Barkev, and George Anserlian ran a workshop that produced copper plates. Hagop Anserlian (Bedros’s brother), who worked for the railway company in Aleppo, moved to Beirut in 1945 and was employed by the Lebanese railway company, initially as a locomotive mechanic and later as an employee.

The craftsmen of the Anserlian family were best-known for the copperware they crafted. They could take a single sheet of copper and hammer it into a beautiful pot, chalice, plate, spoon, fork, knife, tub, etc. in just a few hours. Their staple products were distillers and plates. They also made children’s toys out of copper. Their masterpieces were their lidded braziers, which were up to a meter high, and bore delicate inscriptions and engravings. They would be placed in the center of homes. Another masterpiece was a trophy crafted by Barkev Anserlian, which bore beautiful engravings of famous figures such as Anastas Mikoyan, Marshall Bagramyan, and Lenin. This trophy was made in 1946 as a gift to the Armenian Repatriation Committee during the repatriation movement, but remained in Beirut before being taken to its final destination, Boston.