Giragos Mgrdichian Collection – Athens

Author: Ani Apigian, 06/09/2023 (Last modified: 06/09/2023) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

We were first introduced to the history of the Mgrdichian family by Giragos Mgrdichian during Houshamadyan’s workshop held in Athens in collaboration with the Armenika periodical. After the workshop, we once again met with Giragos, the former principal of the Armenian Blue Cross Zavarian School of Kokkinia, to hear more from him. He presented his family’s history to us with candor and emotion.

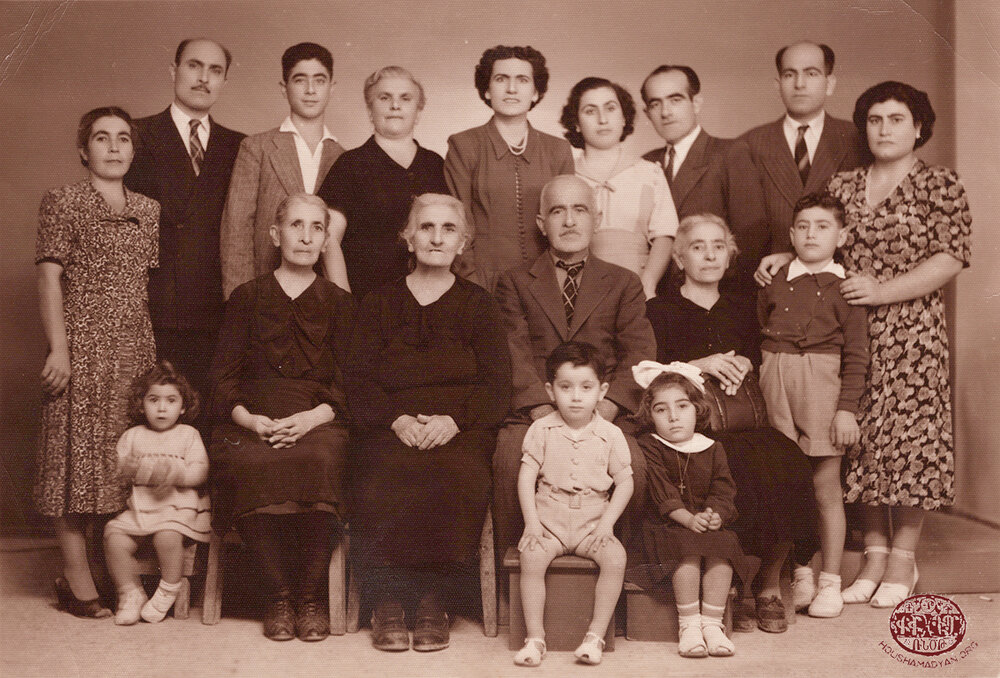

Giragos’s maternal grandfather, Manoug Khachadourian, was born in Cordelio (present-day Karşıyaka), on the coast of Smyrna. Later in life, he moved to Manisa. Manoug was a grape farmer and owned vast vineyards in the Upper Neighborhood of Manisa. He sold the raisins that he made from the grapes that he grew. The Upper Neighborhood, which was also known as the Upper Village, was home to about 150 households. It was entirely Armenian-populated. Most of the neighborhood’s residents were weavers, but grape farming was also a common occupation.

Manoug Khachadourian met Mary Ipranosian and wished to marry her and move to Constantinople. At first, Manoug’s parents opposed this marriage. However, they were soon persuaded, and Manoug and Mary married with their parents’ blessing. They settled down in Manisa. The couple had two daughters: Gula, and two years later, Trfanig. Gula was the future mother of Giragos Mgrdichian.

In 1922, prior to the Asia Minor Catastrophe, Manoug foresaw the imminent danger and moved his family first to Smyrna, then to Greece, traveling by ship. On the way to Smyrna, Gula and Trfanig lost all the gold jewelry that they carried. Manoug succeeded in moving all members of his family to the city of Mytelene on the island of Lesbos. These included his wife, Mary; Mary’s sister, Hayganoush; Gula; and Trfanig. However, as harvest time was near, Manoug decided to return to Manisa to harvest his grapes and make shira and raisins. His plan was to return to Mytelene when he finished, then to eventually return to Manisa with his whole family, as he still believed that the troubles would soon end. Unfortunately, all trace of Manoug was lost after his separation from his family in Smyrna. Most probably, amid the widespread chaos, he was killed by Kemalist forces like many other Armenians.

The surviving members of the family spent a very short amount of time in Mytelene, then proceeded to Piraeus. We know that during the 1921-1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe, thousands of Armenians found shelter in Mytelene, the capital of the island of Lesbos in the Achaean Sea. A small Armenian community was established on the island, and in 1921, an Armenian school was built there.

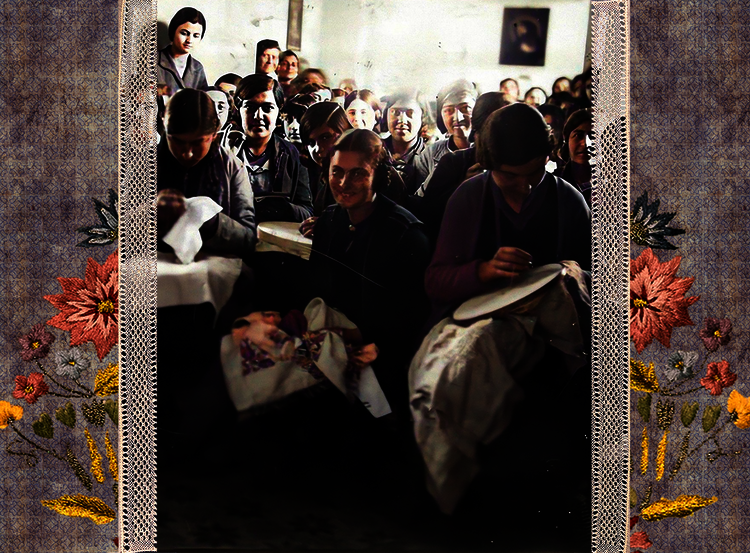

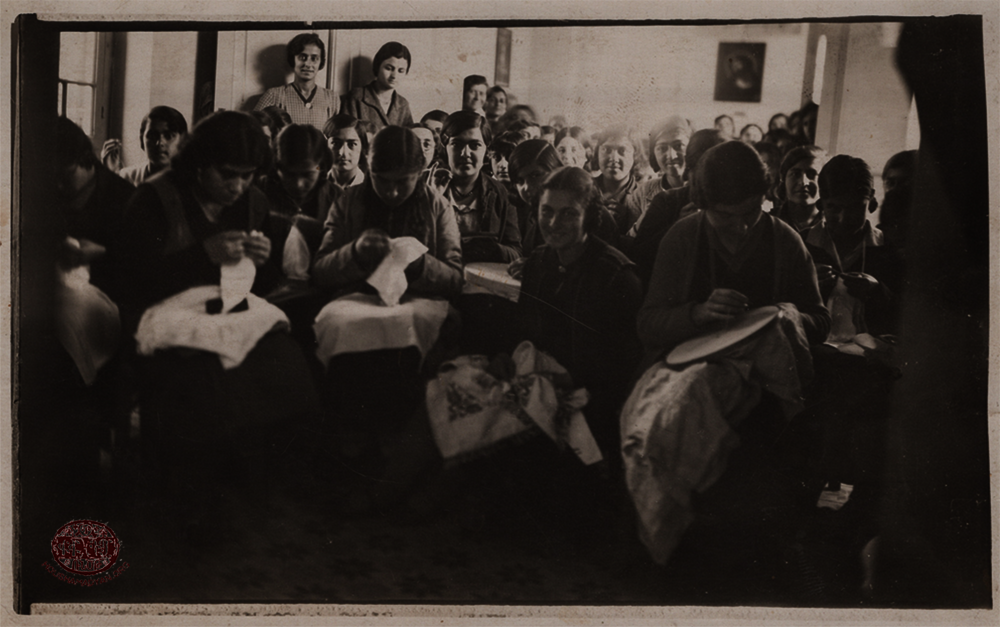

Mary, Hayganoush, Gula, and Trfanig, after their arrival in Piraeus, spent several months wondering from one place to another. From Piraeus, they moved to Kaisariani, then Thiseio. Finally, they settled down in the Lipazmata refugee camp (often called Lipazma in Armenian sources) near the port of Piraeus. The camp was home to 4,000 refugees (500 families), mostly widows and children, who lacked access to the basic necessities of life. In the early 1920s, about 200 Evangelical Armenians had also settled down in the camp, alongside their pastor, Reverend Haroutyun Adjemian. This community had established its own separate “neighborhood” within the camp. Giragos Mgrdichian recalled that at this point in the camp’s history, conditions were relatively bearable. The Mgrdichian family was able to settle down in the Evangelical neighborhood. There were two schools in the refugee camp – the school of the American Near East Relief organization and the Adjemian Armenian Evangelical School. Giragos’s mother, Gula, and his aunt, Trfanig, attended the Adjemian School.

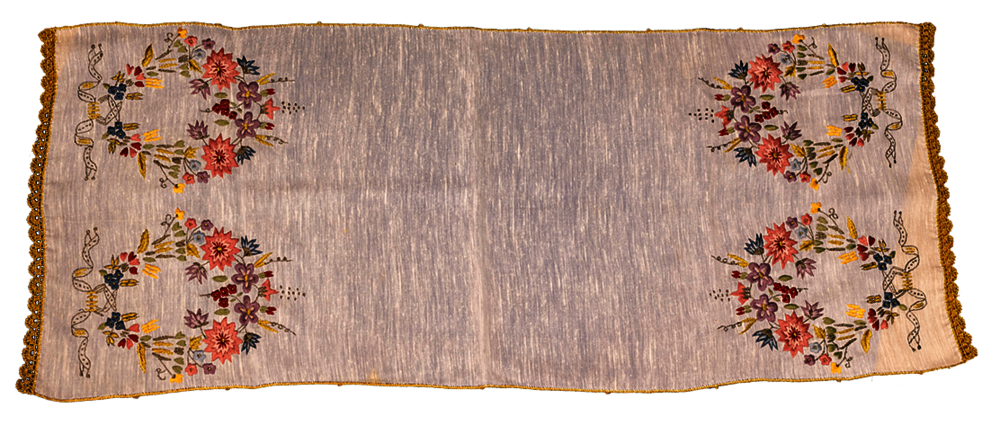

The Adjemian School was trilingual (pupils were taught Greek, Armenian, and English). It was also coeducational, which was notable, as coeducational schools officially began operating in Greece only in 1929. The school offered knitting/embroidery classes, and the students were taught how to play the mandolin during singing and music classes.

Gula quickly learned how to play the mandolin, and both sisters became proficient embroiderers. After graduating, Gula supported the family by selling her embroidery.

Giragos’s grandmother, Mary, was a homemaker. Her sister, Hayganoush, worked day and night in the Palandjian weaving workshop in Piraeus to earn a living. This weaving workshop, owned by Artin Palandjian, produced linens, tablecloths, towels, and sheets. In 1926-1927, approximately 100-150 workers were employed by the workshop, operating 200 looms. The workshop was relatively advanced for the time. It had its own electricity generation system, which also supplied electrical power to local homes. It was during these years that architect Artin Palandjian also opened a public bath in the city, called Balkania. In 1925, he built another public bath in Kokkinia, this time called Asia Minor, which served the thousands of refugees in the city.

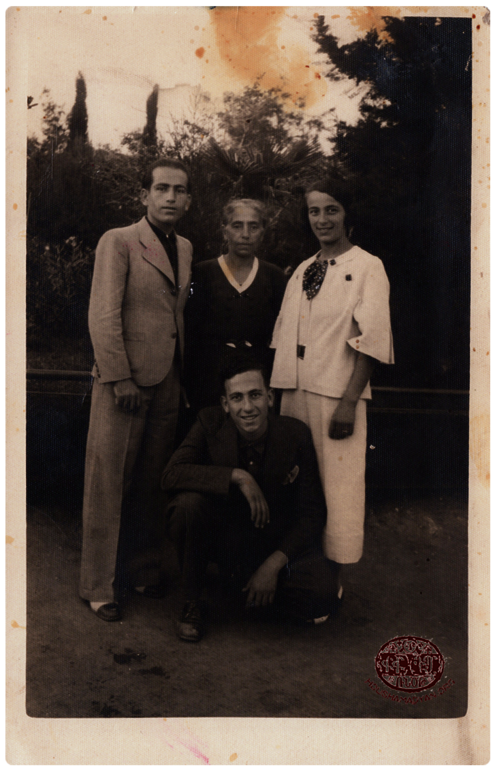

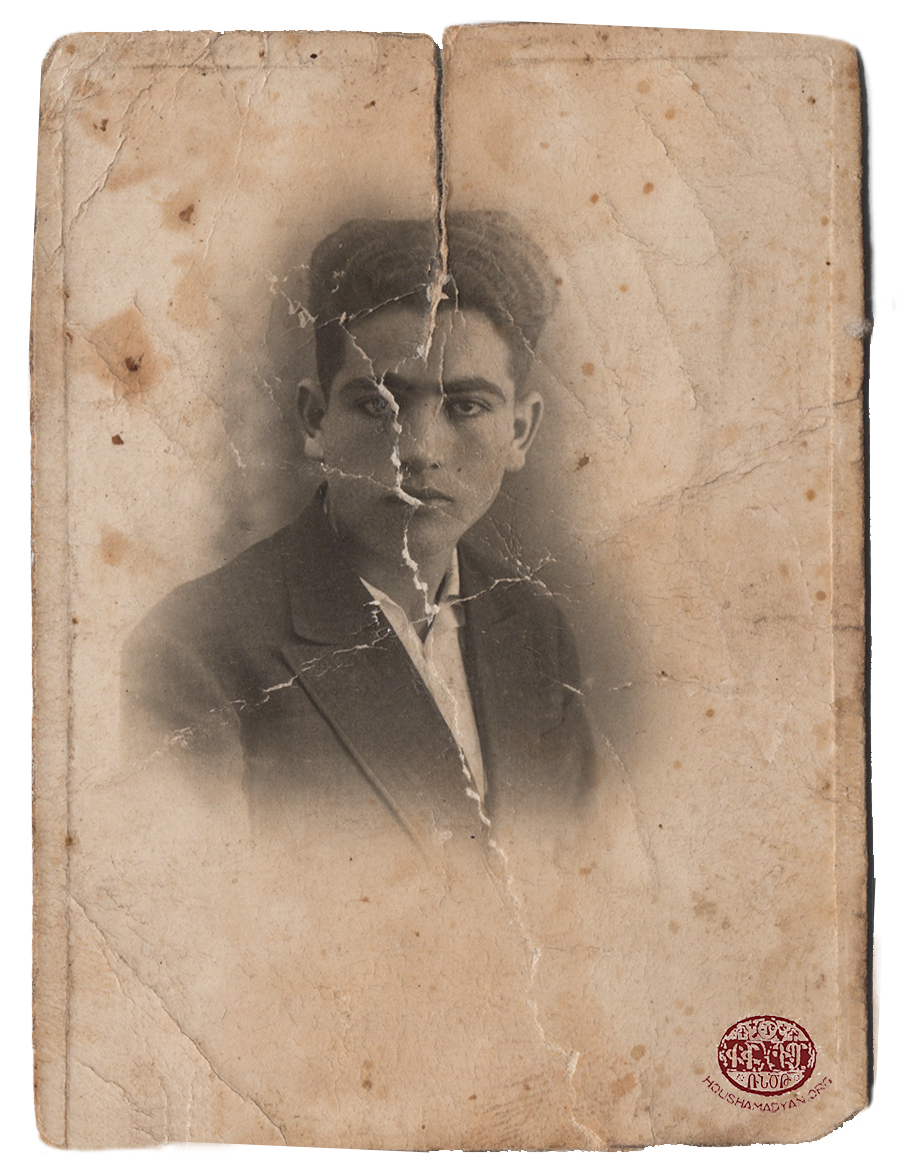

Giragos’s father was Mgrdich Mgrdichian. He, too, hailed from Manisa. Giragos’s grandfather was Hovhannes, and his grandmother was Mary (nee Chobanian). They had three children, Vartanoush, Mgrdich, and Krikor. They were a family of weavers, and lived in the Lower Neighborhood of Manisa, which was also known as Malta. The neighborhood was home to 500 families. The main source of income in the city was manisa fabric weaving, and almost every household in the neighborhood owned a loom.

Mgrdich’s family arrived in Greece in 1922, with Mytelene being their first stop. Unfortunately, amid the chaos of their forced departure from Smyrna, Hovhannes was left behind. Thankfully, he was able to find a way to escape the Kemalist forces and was reunited with his family in Mytelene a week later. From there, the family took a ship to Piraeus and settled down in the Lipazmata refugee camp. Mgrdich attended the Adjemian School, where he first met Gula, his future wife.

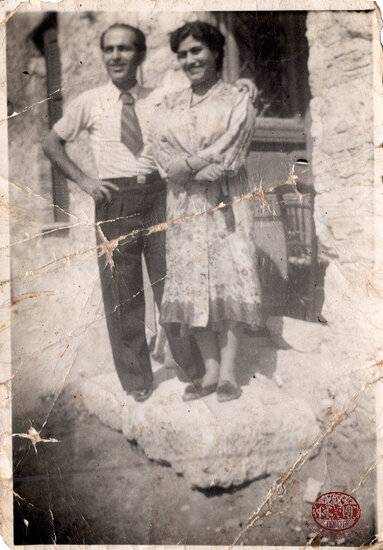

Mgrdich was a cobbler, and Gula an embroiderer. Giragos, their son, was born in 1941. During the Second World War, the port of Piraeus was bombed by the British Royal Air Force. The target was the German military, but Armenian homes in nearby Lipazmata were also destroyed. Consequently, many Armenians, including the Mgrdichian family, moved to Kokkinia.

Trfanig moved to France in 1952. There, she married and started a family. She had three children: Hrant, Markarid, and Hagop. Her husband died at a young age. Trfanig worked in a boarding school.

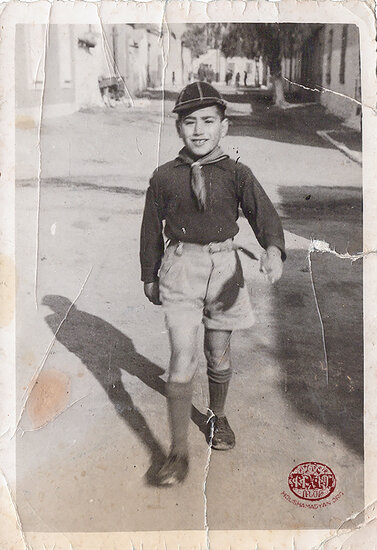

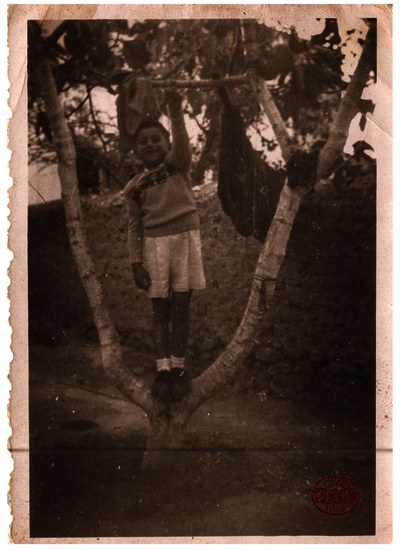

In Kokkinia, Giragos and his family lived outside the refugee camp, in a neighborhood with few Armenians, surrounded by local Greek families. Giragos’s playmates were Greek children. He constantly faced hostility and prejudice, often hearing terms like Armenoboch or skato armenis (“Armenian excrement”) directed at him by local Pontic children. Still, thanks to his boyish enthusiasm and ingenuity, he forced himself into his playmates’ circle. Soon, the hurtful comments ceased, and he gained the respect of all. Throughout his childhood, Giragos enjoyed playing karagoz (Turkish shadow puppetry), which endeared him to the other children. Together, they would make the karagoz figures, which required a certain level of skill and precision. Their “workshop” consisted of the train tracks of Kokkinia. They would find various metal items, which they would place on the rails. The passing trains would flatten these items, and then the boys would mold them into the desired shapes. Once the figures were made, the boys would stage the karagoz plays, which would be held in one of the local courtyards. They would even charge the spectators an entry fee. They would hang a sheet and light candles behind it, thus creating the required setting for shadow puppetry.

Giragos attended the Zavarian School of Kokkinia, which was founded in 1927. The school initially had an enrollment of 80 pupils, and its first principal was Zakar Zakarian. By the 1928-1929 school year, its enrollment had already skyrocketed to 250 pupils, and the principal was Sos Vani.

Giragos was not excited about attending an Armenian school, as most of his friends were Greek and he had no Armenian friends in his neighborhood. However, as he would later state, his attitude gradually changed. He began making Armenian friends and became imbued with Armenian patriotism. He remembered that in those years, he was greatly impressed by Antranig Dzarougian’s poem, Oukhd Araradi [A Vow to Ararat].

In the sixth grade, Giragos faced a dilemma. The Zavarian School only offered six years of education, and he had to decide what to do next. Like most Armenian refugees in Greece, he had neither a passport, nor Greek citizenship. Each year, he had to renew his Greek residency papers, which listed his nationality as “Turkish” and “apatride” [lacking a homeland]. It would be pointless to continue his studies within the Greek educational system, because as a non-citizen, almost all careers would be out-of-bounds for him.

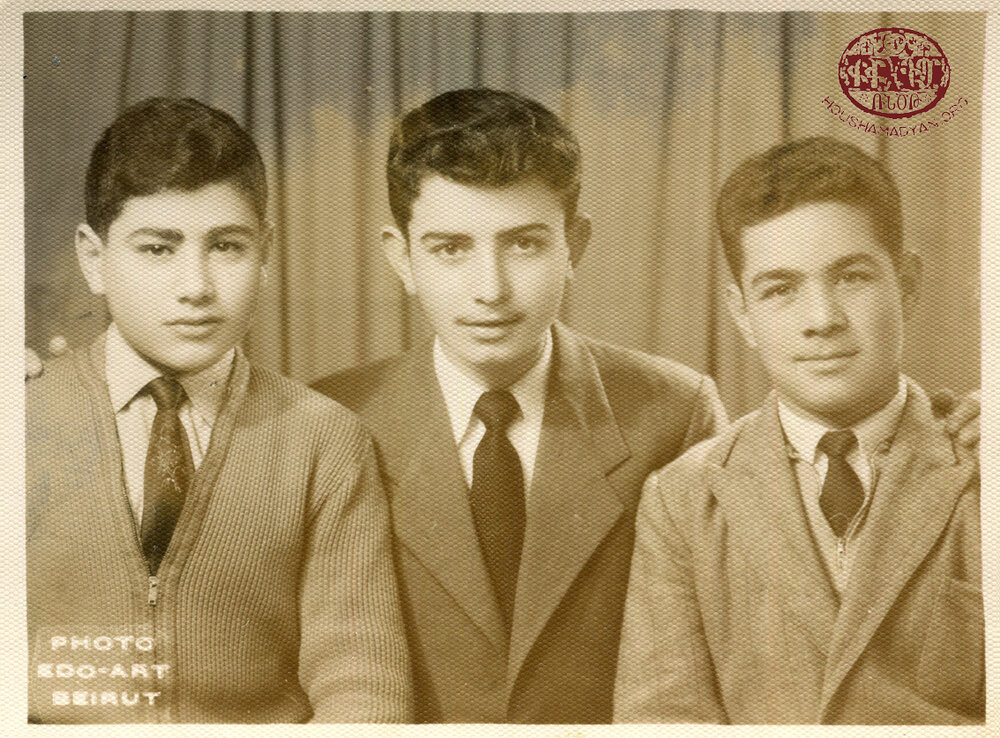

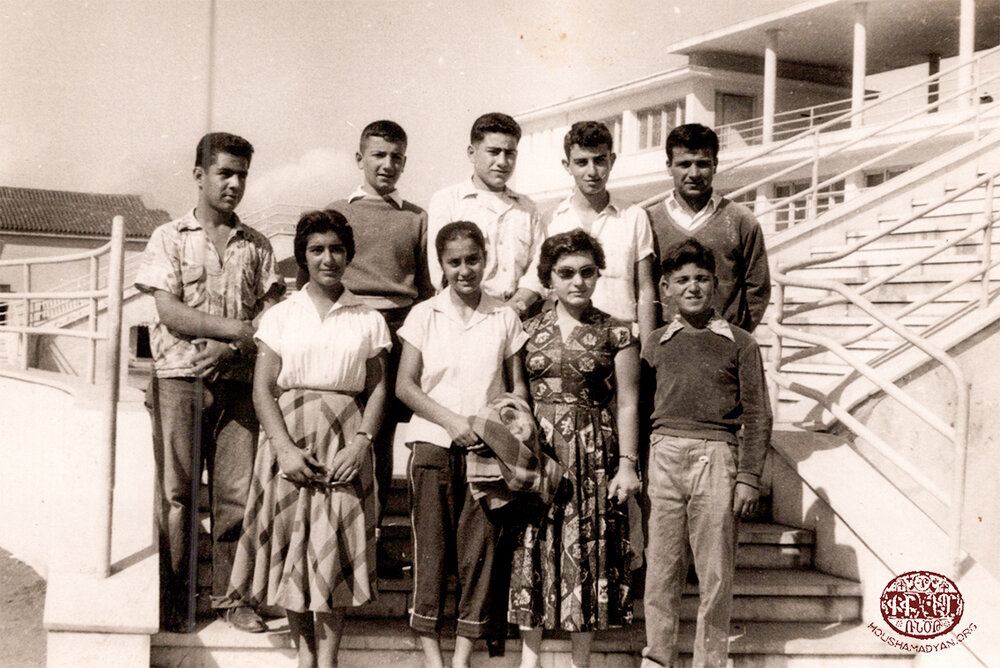

At this time, the principal of the Zavarian School was Onnig Zakarian. He became interested in Giragos’s situation and encouraged him to continue his studies outside of Greece. Gula, Giragos’s mother, was determined to offer him the best possible education. The original plan was to send 13-year-old Giragos to the Melkonian School in Cyprus. However, this plan was changed, and the family decided to send Giragos to study at the Karen Jeppe Djemaran [Lyceum] in Aleppo. In the summer of 1955, three teenagers, Giragos Mgrdichian, Haroutyun Mkhigian, and Hagop Sevagian, boarded a ship to Beirut. Mkhigian and Sevagian planned to attend the Nshan Palandjian Djemaran in Beirut (the latter was already a student at this school and had been visiting Greece for the summer), while Giragos planned to proceed to Aleppo.

The family expected Giragos to receive the visa allowing him to travel to Aleppo on the Lebanese-Syrian border. However, upon arrival, he was denied a visa. He spent the night on the border, then returned to Beirut in the morning on a bus. Upon his arrival in the Lebanese capital, the family decided that he would instead attend the city’s Nshan Palandjian Djemaran, which his two Greek-Armenian friends also attended. He was a student at this school for seven years. His mother, Gula, sold her embroidery in various stores in Athens to pay Giragos’s tuition fees. Giragos would travel back to Greece each summer to be with his family.

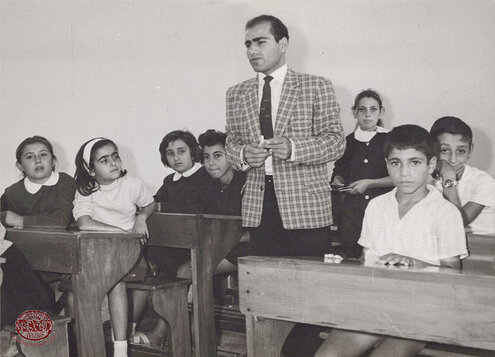

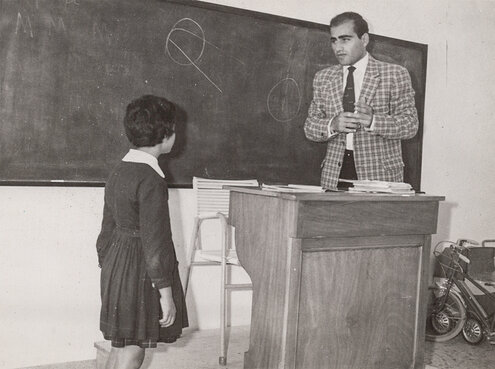

Giragos was a bright student. In his last two years at Djemaran, he was tasked with keeping track of other students’ academic progress. After spending seven years as a pupil of this institution, Giragos permanently returned to Greece and immediately expressed a desire to teach in one of the Armenian community’s schools. In 1962, he was employed as a teacher in the newly built Levon and Sophia Hagopian School, in the Fix neighborhood of Athens. He kept this position for seven years. The principal of the school, at the time, was Onnig Zakarian. In the late 1960s, Giragos became a Greek citizen. He served in the Greek Army in 1969-1970. In 1971, he married Vart Torosian. They had two children, Varant and Viken.

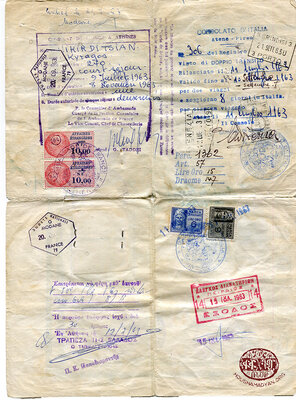

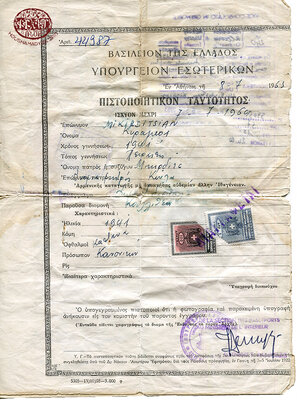

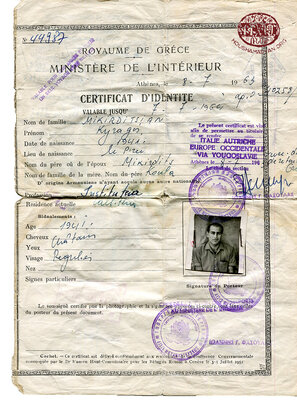

The Greek identification card that Giragos Mgrdichian used to travel to France in 1963.

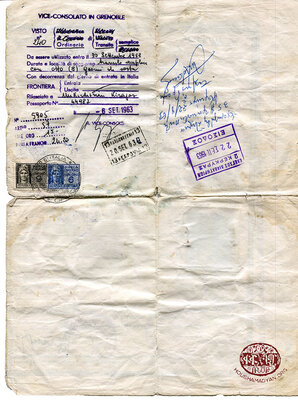

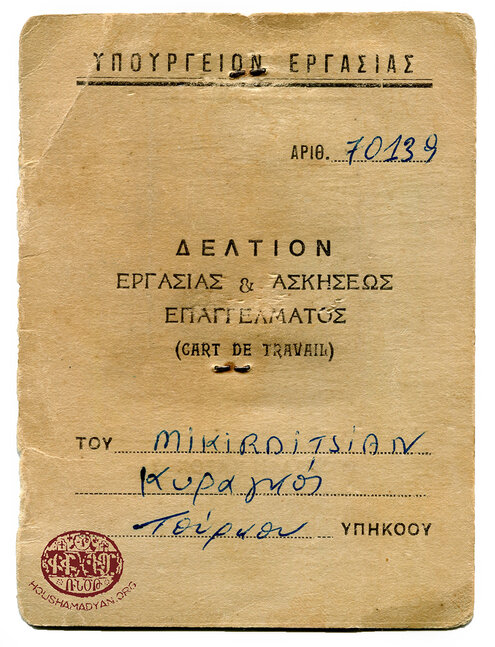

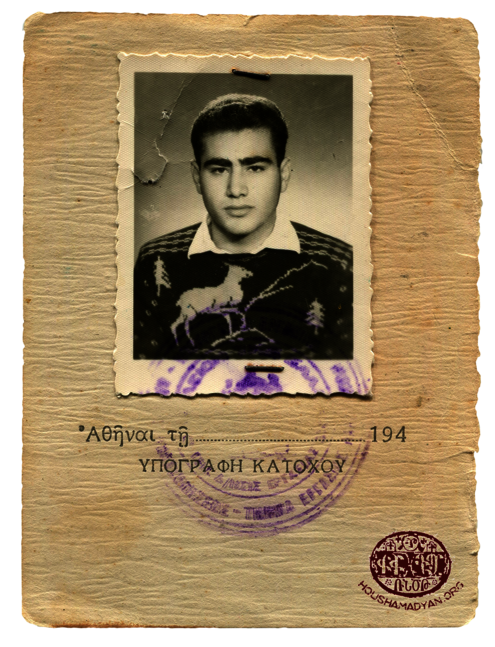

Giragos Mgrdichian’s Greek work permit, which he obtained when he was employed as a teacher by the Levon and Sophia Hagopian School of Athens. Below his name and surname is a note indicating that he was a “Turkish citizen,” despite the fact that he was born in Greece. He became a Greek citizen only in 1968.

Giragos’s father, Mgrdich, died in 1998. His mother, Gula, died in 2006.

From 1971 to 2007, Giragos Mgrdichian served as the principal of the Zavarian School of Kokkinia.

Today, Mr. Giragos and his wife, Vart, are enjoying life with their two grandchildren.