Kalfayan Collection – Thessaloniki

24/07/23 (Last modified 24/07/23) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

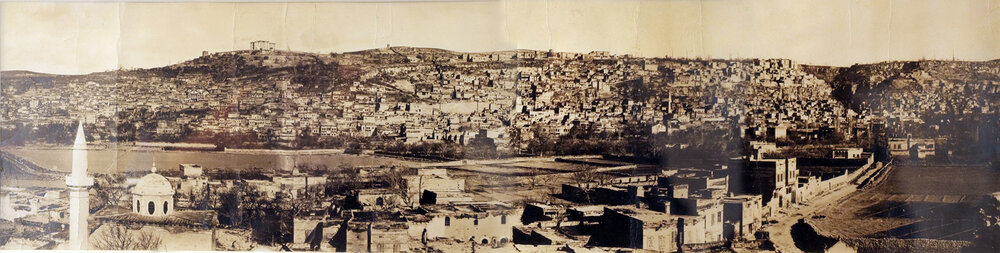

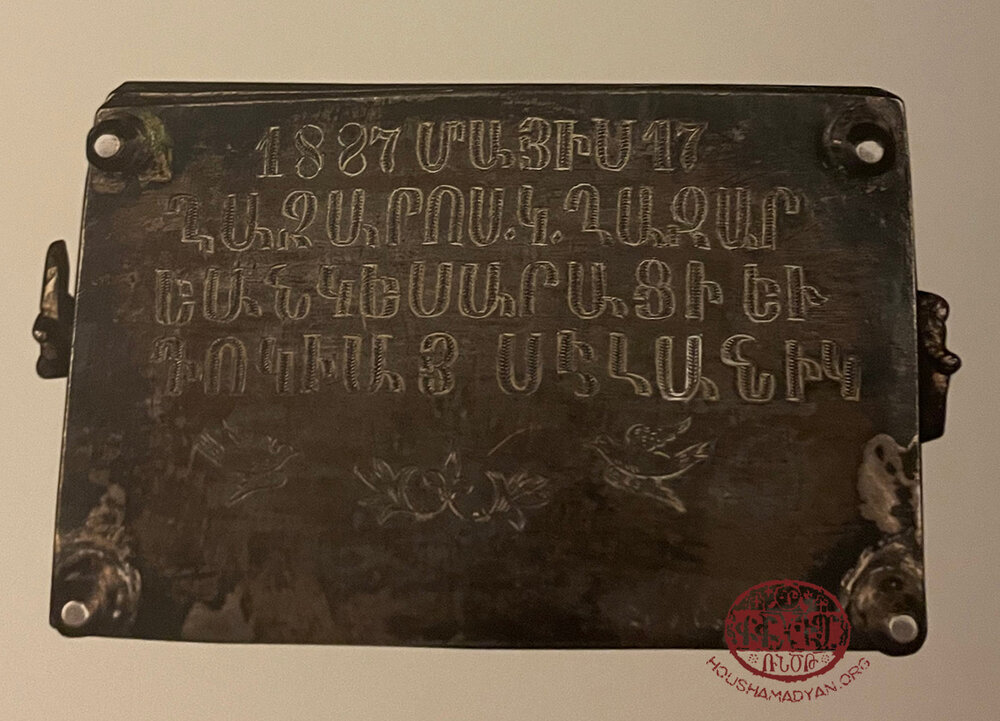

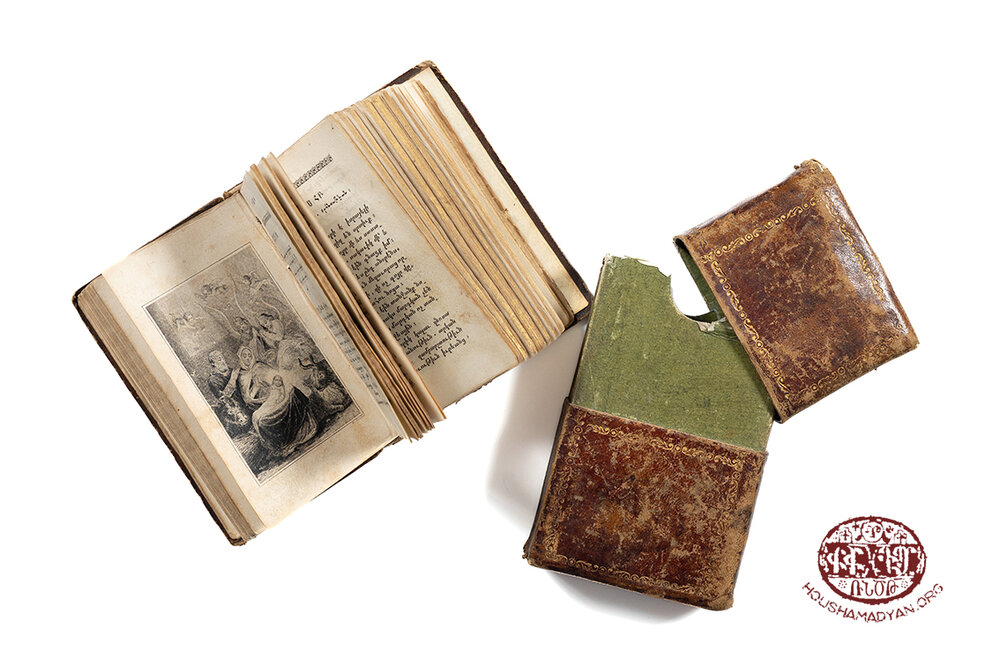

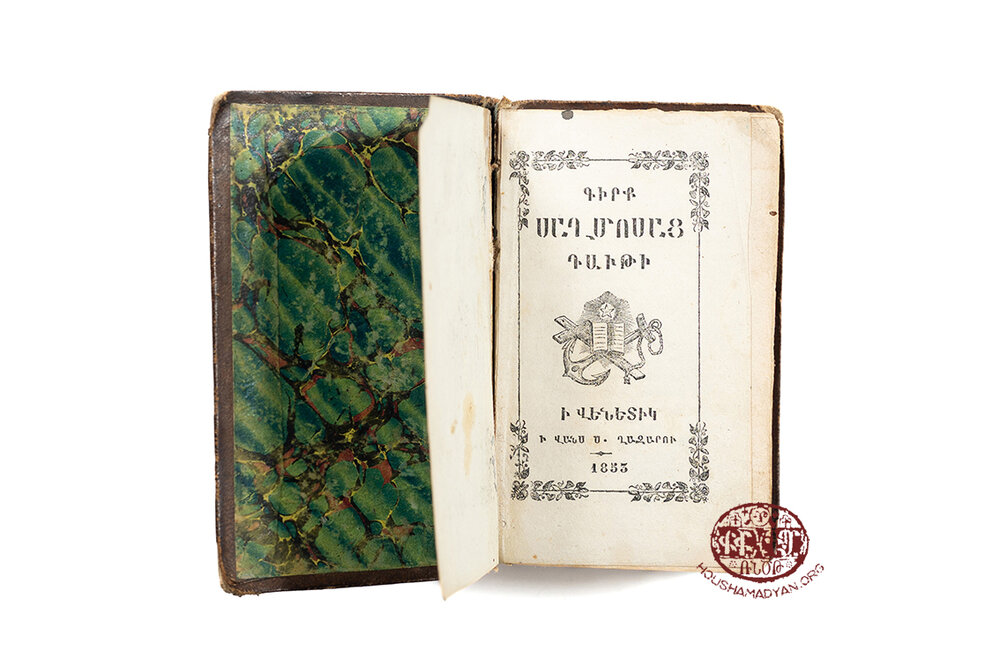

This page presents the history of the Kalfayan family, alongside numerous memory items and photographs that are currently in the family’s possession. The family history can be divided into two branches – that of the Kalfayans, who lived in Talas; and that of the Gazarians/Ghazarians, who also initially lived in Talas, but later moved to Tokat. Both families were prominent in their respective home cities. Garabed Gazarian moved to Thessaloniki in the late 19th century, when the city was still part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Armenian Genocide of 1915 was a devastating blow to both families, of whom very few survived. These survivors began a new life in the 1920s, in the Greek city of Thessaloniki. The Kalfayans and Gazarians became related by marriage, and their lives continued with new vigor and new successes.

Some of the oral testimony and memory items presented in this collection were provided to our editorial team during the workshop organized by Houshamadyan (in collaboration with the Armenika Periodical of Athens) in Thessaloniki on November 13-14, 2021. At a later time, the Houshamadyan team remotely conducted interviews with two members of the Kalfayan family, Arsen Kalfayan and Dirouhi Galileas (nee Kalfayan). We would also like to thank Nvart Galileas and Veronica Mahdessian, who helped collect the photographs presented in this article.

The Kalfayan Branch

The Kalfayans were natives of Talas. Among their oldest ancestors, we know of Avedis Kalfa/Kalfayan, born in the 1820s. The family trade was the crafting of molds used to produce printed fabric, as well as the production of printed fabric. Avedis himself was a talented artist who became a master architect. He was particularly renowned for his talent in designing decorations for homes and palaces. His work can be seen at the Çırağan Sarayı (Palace) and Beylerbeyi Palace. Among the buildings that he built were the Saint Sdepanos Church in the Germir village of the Kayseri region, famous for its cupola; and the Saint Boghos Armenian Church in Tarsus. In 1867, he was invited to Adana to build an Armenian church there. He traveled to the city with Durger Sahag Ousda (according to Alboyadjian), who was still a journeyman architect at the time. Unfortunately, Avedis died later, and Durger Sahag finished the construction of the church. [1]

Avedis Kalfayan’s children were Peprone, Madteos (born in 1870), Arsen (born in 1859), Haroutyun (born in 1871), Roupen, Helen, and Serovpe.

In Talas, Madteos Kalfayan was a non-certified lawyer. Haroutyun was sent to Constantinople at a young age, where he received secondary education, and then studied law at the Ottoman State University. Arsen also studied law and was a practicing lawyer like his brothers. During the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid, Arsen and Haroutyun were known for their revolutionary activity. Arsen was initially a member of the Hunchak Party. He was sentenced to seven years in prison as a revolutionary by a court in Ankara. He was first interned at the central prison of Constantinople, then, after a few months, he was exiled to the island of Rhodes. He remained in Rhodes for two years, after which, in the 1890s, thanks to appeals by Patriarch Madteos Izmirlian and the ambassador of the United Kingdom, he was pardoned and returned to Constantinople, where his brother Haroutyun lived. Arsen later joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). Haroutyun was among the first generation of ARF operatives. His pseudonym was Vahram. In 1896, in response to the armed raid on the Ottoman Central Bank, organized by the ARF, Sultan Abdul Hamid unleashed a wave of massacres and arrests across Constantinople. Arsen Kalfayan was arrested and sent to Talas. Haroutyun fled to Bulgaria, and from there he proceeded to Egypt, then to Switzerland.

In Talas, Arsen continued to work as a lawyer, this time in partnership with his brother, Madteos. Arsen was also a member of the city’s Armenian political council. Haroutyun would return to Constantinople in 1908, after the Young Turk revolution. Between 1912 and 1915, he served as the mayor of the Makriköy and Ay-Stephano neighborhoods of Constantinople.

Madteos, one of Avedis’s sons, married Vehanoush. They had two sons, Roupen (born in 1902) and Serop (born in 1906); and five daughters, Mayreni (born in 1902), Zarouhi, Araksi, Peprone, and Anahid (born in 1910). Mayreni and Roupen were twins. Another child, Krikor, died in infancy. Another of Avedis’s sons, Arsen, married Makrouhi Gulbenkian (her father’s name was Kasbar). They had seven children, Roupen, Akabi, Avedis (1900-1977), Souren, Misak (born in 1909), and Verjin (1892-1944). Haroutyun also married (his wife’s name is unknown), and had one son, Avedis. Serovpe’s children were called Avedis and Yepraksi. Helen had four children, Haygouhi, Isgouhi, Apel, and Dikran.

When the Armenian Genocide began, Haroutyun was among the prominent Armenians arrested on April 24, 1915. He was in a group deported to the town of Ayash, and he was killed there. The family’s oral history has preserved an alternative version of these events, which claims that Haroutyun never made it to Ayash, but that he was killed by Turkish policemen in the courtyard of his home in Constantinople. In Talas, the arrests of prominent Armenians began in June 1915. Among the detainees were the brothers Madteos and Arsen Kalfayan. For approximately a month, they were kept in the jail of Talas, where they were tortured. Then, they were sent to the jail of Aleppo where they remained for 25 days. Subsequently, Arsen was among a group of detainees who were deported to Ourfa in chains. They were killed somewhere along the way. As for Madteos, the details of his death are not clear. We only know that he died during the years of the Genocide of typhoid fever.

The other members of the Kalfayan family also experienced the horrors of the Genocide. Madteos’s wife, Vehanoush, and their children, were also deported, eventually reaching Aleppo. At the time, one of the couple’s daughters, Anahid (1910-1941), was still a little girl. An Aleppine family adopted her and gave her shelter. The same family moved later to Lebanon and then to Marseille, where Anahid married a Kouyoumdjian and had four children: Vehanoush/Rose (1929-2006), Monica (born in 1931), Alice (1933-2010) and Raymond (1940-2017)). Another one of the Kalfayan’s daughters, Araksi, died in Aleppo during the deportation years. Similarly, Arsen’s wife, Makrouhi, and their children, were deported. After suffering greatly along the way, they reached Aleppo. But they did not remain in the city for long. They were deported once again to Hauran, where the Armenian refugees were in the throes of famine and epidemics. Fortunately, the family was able to leave Hauran and make its way to Damascus, where conditions were relatively bearable. Avedis Kalfayan’s (Arsen and Makrouhi’s son) biography states that during the years of the Genocide, Vehanoush Kalfayan and her children, after spending some time in Aleppo, fled the city and settled down in Damascus until the end of the war.

After the Armistice of 1918, two of Madteos’s sons, Roupen and Serop, were sent to the American college of Tarsus/Darson (Cilicia). Madteos’s wife, Vehanoush, decided to return to Talas with her other children. They joined the procession of refugees returning to the city. Only fragmentary information about their journey has survived. Apparently, on the way to Talas, the refugees wished to enter an Armenian church in a village or a city along the way to pray. Once they entered it, the local Turks locked the doors and set the church on fire. Vehanoush and her daughters were killed.

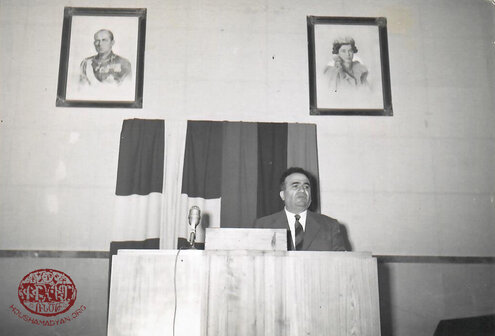

The Kalfayan family’s oral history has preserved another anecdote, as told by Garabed Kalfayan. In 1962, he was invited to Aleppo and Damascus to deliver keynote speeches during events celebrating the anniversary of Armenian independence on May 28. Before his departure, his father, Roupen, asked him to visit the train station of Aleppo, saying: “When you get to that spot, look to the right, and cast your gaze into the distance. Somewhere over there is the grave of my father, Madteos.” It was said that Madteos’s two sons, Roupen and Serop, had dug their father’s grave with their own bare hands.

Evidently, none of the members of the Kalfayan family ever returned to Talas. It is unclear what happened to their home and estates that they left behind.

After matriculating at the college of Tarsus, Roupen and Serop moved to Greece. The country was completely unknown to them. They had no relatives or friends. Initially, they settled down in Xanthi. Both men spoke English. Roupen began working as an English translator in the tobacco factories of the city, mainly the American Grand Tobacco factory. He also worked as an Armenian teacher in the city’s Armenian school from 1923 to 1926. Meanwhile, Serop was employed by a local taxi driver.

Thessaloniki was also where the Gazarian family lived – they, too, were natives of Talas and Tokat. Roupen had heard that the Kalfayans and Gazarians were related, either by blood or by marriage. So, he contacted them. When Garabed Gazarian learned that the two youths were in Xanthi, he immediately invited them to Thessaloniki.

And so, Roupen and Serop Kalfayan’s first meeting with the Gazarian family occurred in Thessaloniki. Roupen would later marry Nvart Gazarian, who was Garabed and Dirouhi’s daughter. Serop married Alice Boghdadjian and had three children: Madteos (1944), Vehanoush (1946) and Zabel (1954). Madteos married Nancy Bedjian and had two children: George and Lisa. Vehanoush married Nourhan Bledjian and had two children: Dickran and Nektar. Zabel married Micheal Nini and had two children: Kostis and Alice.

Back row, left to right: Onnig Papazian (Rodosto), Nigoghos Ashdjian (Thessaloniki), Hrant Chitdjian (Nicomedia/Izmit), Aghaminon Mantamatiodis, Nerses Mouradian, Levon Boghosian (Garin/Erzurum), Vartkes Gogosian (Eskishehir), Noubar Yesayan (Bursa), Anahid Vishabian, and Fotini Hadjianastasio. Second row from the back, standing, left to right: Armenouhi Mkhulian, Ebrouhi Balabanian (Afyonkarahisar), Koharig Khoubeserian (Eskişehir), Madelene Aleksanian (Constantinople), Suzanne Hagopian (Biledjik), Maritsa Khachadourian (Thessaloniki), Aghavni Yazudjian (Rodosto), Perouz Manougian (Afyonkarahisar), Vrej Malkhasian (Constantinople), Harout Kalenderian (Sivrihisar), and Onnig Boghosian (Adapazarı).

Seated, left to right: Setrag Paraghamian, Khosvor Khandjian, Sdepan Sdepanian, Tovmas Boyadjian, Ghazaros Gazarian, Yanni Eftimiadis, Yughaper Vishabian, Manishag Kevorkian, and Aghavni Eolmezian.

Sitting on the ground, left to right: Hovhannes Khachadourian (Thessaloniki), Vrej Zakarian (Antalya), Garbed Andonian (Bandırma), and Khachig Poghharian (Adapazarı).

Back row, left to right: Hagop Mardigian (Kütahya), Nerses Mouradian, Nazaret Mkhlian, Madamatiodis, Khosrov Khandjian, Yeram Bdoughian, Anahid Vishabian, and Sdepan Ghzmerian (Kütahya). Second row from the back, standing, left to right: Momdjian (first name illegible; Afyonkarahisar), Anahid Suvadjian (Rodosto), Azniv Dourgoutian (Eskishehir), Verjin Djurukian (Eskishehir), Azadouhi Kekligian (Kütahya), Ophelia Keorhadjian (Smyrna), Dikranouhi Mghrafian (Afyonkarahisar), Nouritsa Sufuntuyan (Adapazarı), Yeghsapet Suvadjian (Smyrna), Yevkine Varteresian (Nicomedia/Izmit). Seated, left to right: Aghavni Eolmezian, Sdepan Sdepanian, Tovmas Boyadjian, an unidentified individual, Ghazaros Gazarian, Yanni Eftimiadis, Setrag Paraghamian, and Yughaper Vishabian.

Sitting on the ground, left to right: Onnig Toumayan, Terenig Ohanian (Moush), Haroutyun Terzian (Afyonkarahisar), Ghazar Ghazmedian (Eskishehir), Jirayr Nadian (Adapazarı), and Onnig Saadetian (Adapazarı).

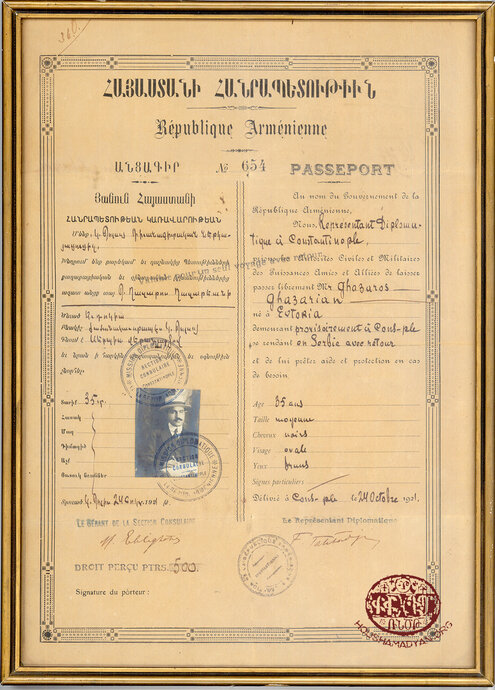

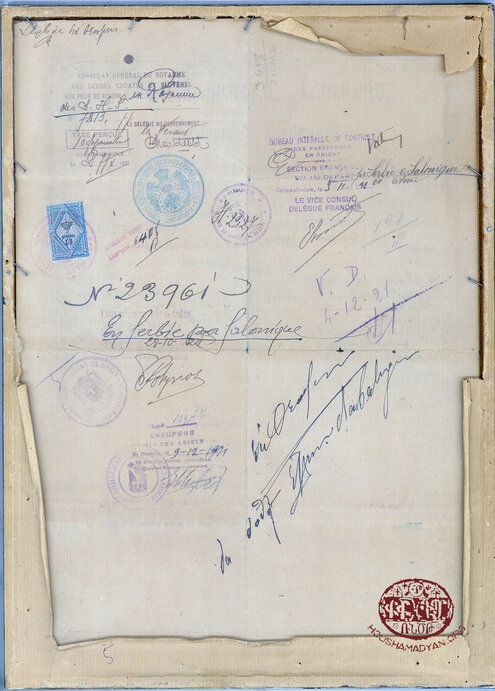

The Gazarian/Ghazarian Branch

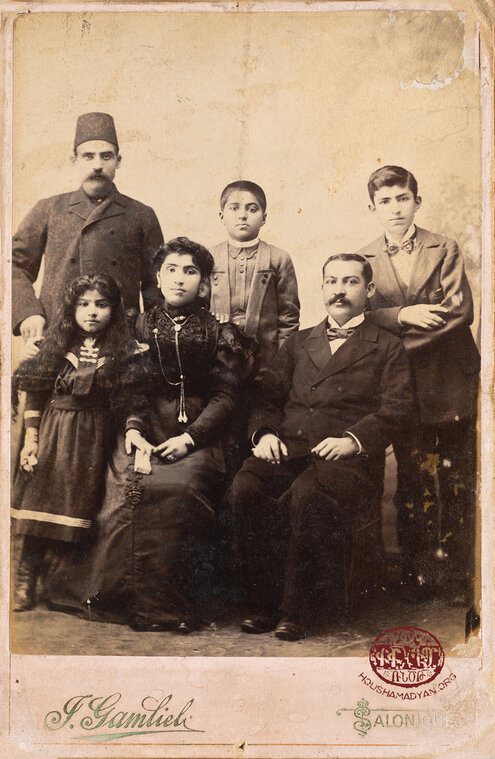

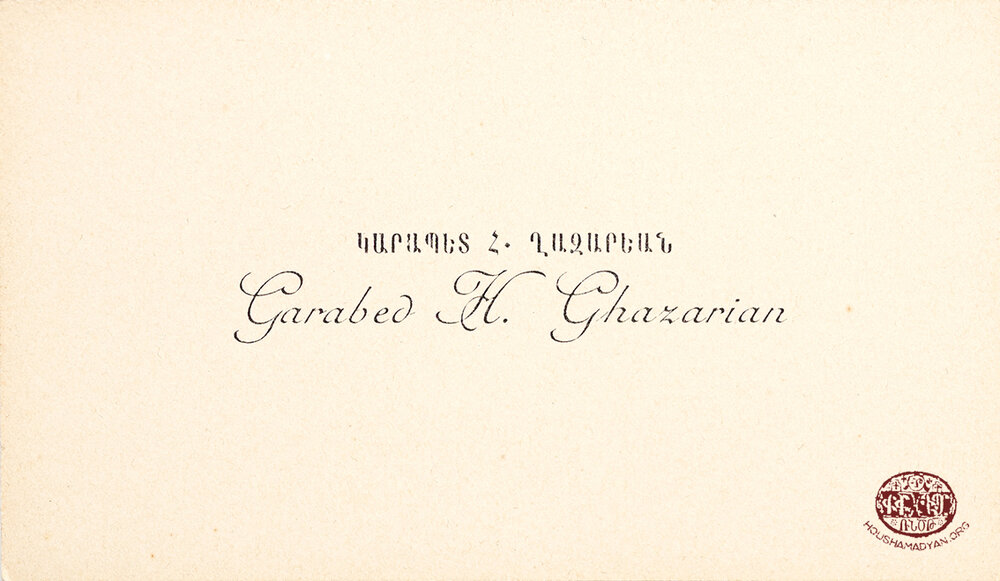

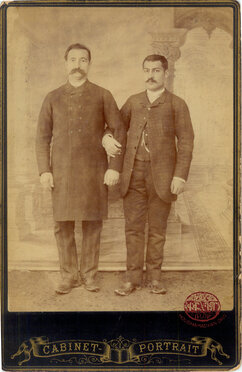

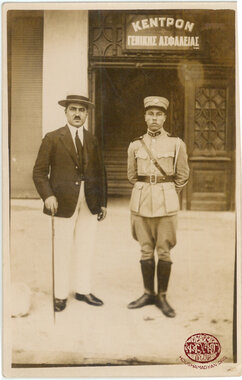

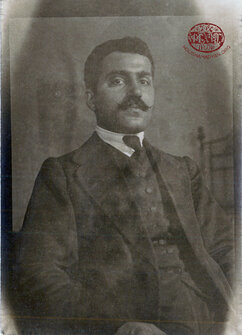

Garabed Gazarian (1865-1931) was a well-known merchant in Thessaloniki. He had a monopoly of the opium trade across the entirety of Greece.

Garabed was born in 1865, in Talas. His father was Toros, better known as Hadji Gazarian Effendi, a well-known landowner. Garabed’s mother was Elmonia. When Garabed was three years old, his family moved to Tokat. Garabed became a prominent merchant at a young age. He was also known was Hadji Agha Gazarian, and worked with the Gulbenkian trading house, which exported products from the area. Garabed was the largest purchaser of the opium grown in the province, which he would store in Tokat before transporting it to Constantinople. He had two sisters. One was called Filor (born in 1878) and would later marry Garabed Shahbenderian (killed in 1915). She had four children: Nerses (1890-1983), Vehanoush, Verjin, Badrig (born in 1912). Filor emigrated later to Bucharest (Romania). The name of Garabed’s other sister is unknown, but we know that she married a Mechitarian and started a family in Sivas/Sepasdia. They had three children: Satenig, Asdghig, Mourad. The husband was killed during the genocide and Asdghig moved to Romania.

It is said that one of Toros Gazarian’s Turkish friends, in 1886 or 1888, secretly warned him that the situation of Armenians across the empire would soon dramatically worsen and that a wave of violence would be unleashed against them. He advised Toros to send his son, Garabed, abroad. Consequently, Garabed left Tokat in 1892 for Thessaloniki, which was, at the time and until 1912, part of the Ottoman Empire. In Tokat, the Gazarian family owned vast estates and arable fields. Garabed spared no efforts to bring his parents to Thessaloniki, too, but Toros refused to move, insisting that Tokat was his homeland. At the start of the Genocide, Toros was arrested in Tokat and publicly beheaded. Afterwards, his severed head was put on display. His wife, Elmonia, as well as other relatives, were deported in various directions and killed en route.

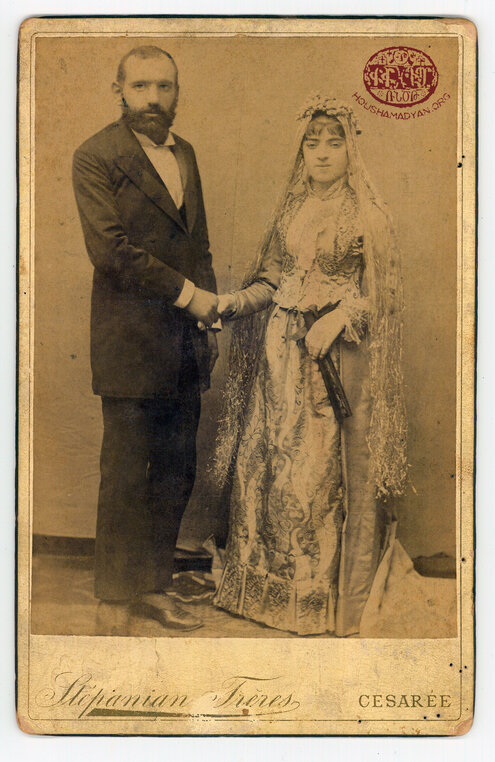

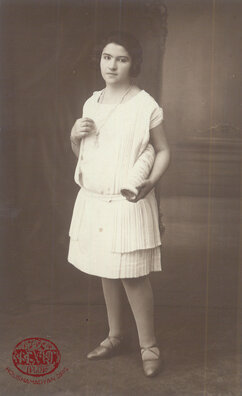

While still in Tokat, Garabed had married Dirouhi Gulbenkian, who was born in the same city in 1868. Dirouhi’s father was Badrig (or Sarkis), and her sister was Makrouhi, who, as we have seen, was married to Arsen Kalfayan in Tokat. Garabed and Dirouhi had two children, Ghazaros (born in 1888) and Veron (1892-1965). Around 1892, Garabed left for Thessaloniki, initially alone. But after some time, Dirouhi and their two children joined him. The couple’s third child, Nvart (1900-1971), was born in Thessaloniki. Evidently, Dirouhi then returned to Tokat, as the couple’s fourth child, Yermone, was born there in 1908 (she would die in 1984). In addition to these four children, the Gazarian family had also adopted Vartouhi Karibian, an orphan who had survived the Genocide, born in 1900 in Tokat. Her father was a friend of Garabed Gazarian’s. Her parents had been killed during the anti-Armenian pogroms in Tokat (date unknown). The Gazarians tracked down Vartouhi, brought her to Thessaloniki, and raised her as their own daughter.

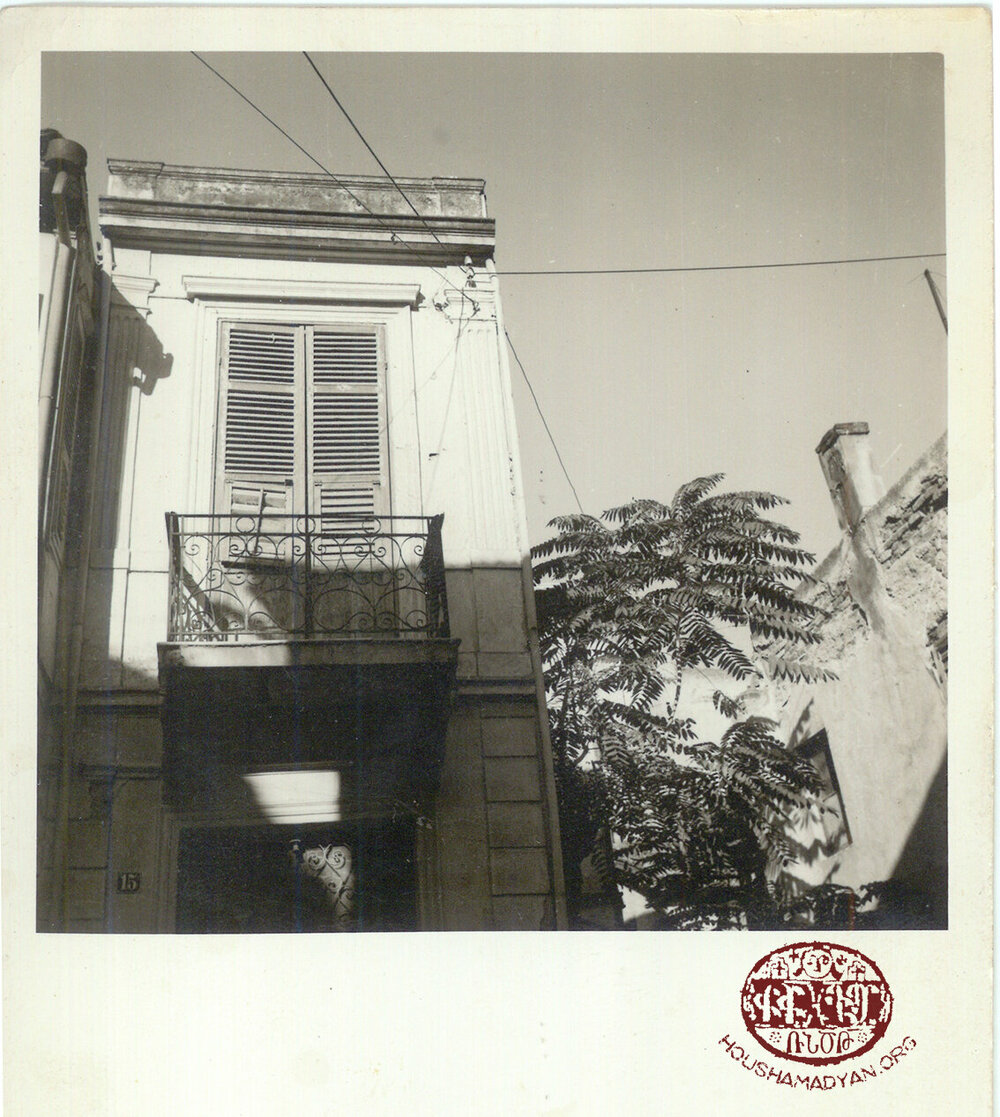

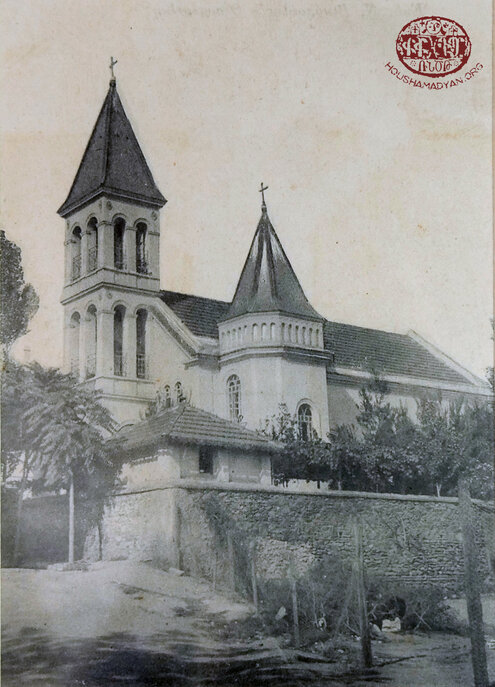

Garabed Gazarian was actively involved in the life of the Armenian community in Thessaloniki. When the community decided to build a church, Garabed was able to obtain a construction permit in his name from the Ottoman authorities. The church was built in 1903. Aside from the Gazarians, other prominent Armenian families that lived in the city at this time included the Puskulian, Amadounian, Ghazarian, Aslanian, Roupinian, and Paul Zepdji (famous photographers) families. They lived in adjacent homes in the neighborhood of the newly constructed church. Previously, the local Armenian community had only had a small chapel, whose altar was now moved into the baptistery of the new church, to the left of the main altar.

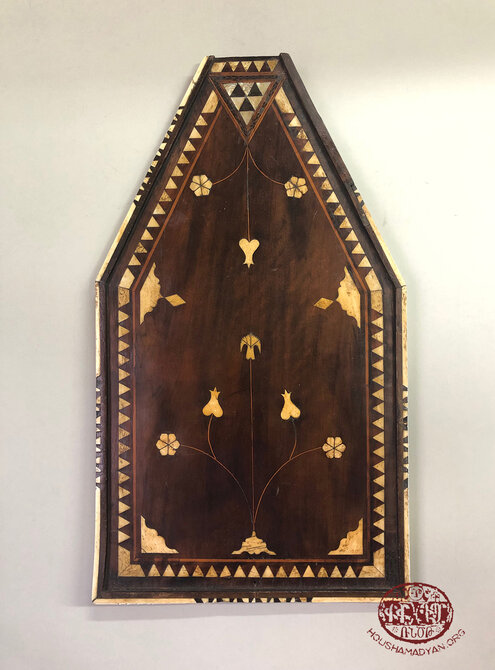

Aside from his involvement in the opium trade, Garabed Gazarian was also a merchant of rugs. In Thessaloniki, he owned his own rug factory, which boasted more than 20 weaving looms.

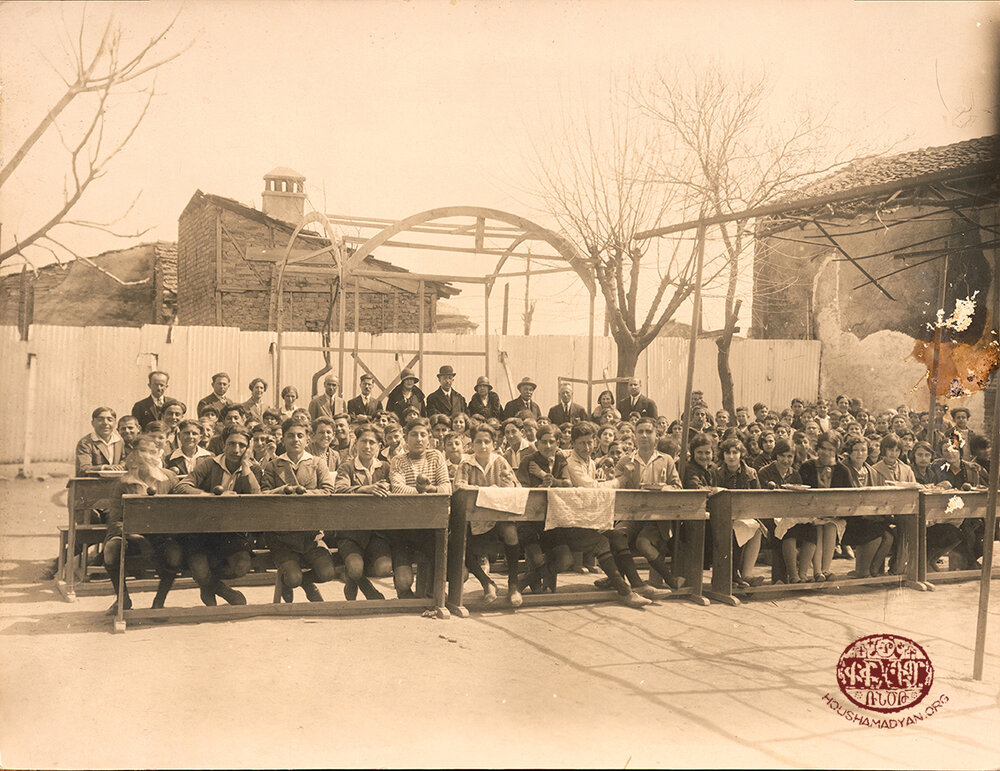

Garabed Gazarian also played an important role in the founding of the Gullabi Gulbenkian School in Thessaloniki. Prior to 1924, the Armenian community of the city only had a kindergarten. The community also had a girls’ choir and offered embroidery classes. After 1922, when a large wave of Armenian refugees arrived in Greece and the size of the Armenian community in Thessaloniki grew exponentially, a decision was made to build an Armenian school in the city. Garabed Gazarian was able to convince the Gulbenkian family of New York to fund the construction of this school, which opened in 1924, at a site outside the city. The school was called Gullabi Gulbenkian in memory of a deceased member of the Gulbenkian family. The original school building was not suitable, and two years later, the school relocated to a more appropriate site (Besh Chinar). Attendance grew to 250 pupils. Garabed was a member of the school’s board of trustees. From 1920 to 1924, he also served as the chairman of the city’s Armenian neighborhood council.

Dirouhi died in 1918, falling victim to the Spanish flu epidemic. Dirouhi and Garabed’s son, Ghazaros, married Verjin Kalfayan, who was the daughter of his aunt, Makrouhi Kalfayan (nee Gulbenkian). Veron married Zacharia Avedikian. The two had a son, Souren. Yermone married Kevork Boyadjian. Vartouhi married Setrag Paghramian, who was born in Bardizag. The two had a son and a daughter, Vahak (born in 1927) and Alice (born in 1937).

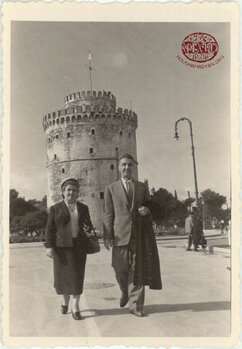

Roupen and Nvart’s Marriage and their Family

Once Roupen and Serop had settled down in Thessaloniki, Garabed Gazarian opened a wood trading business and workshop in the city for them, in 1928. The business sold wood and also made wooden parts for chariots, such as wooden wheels.

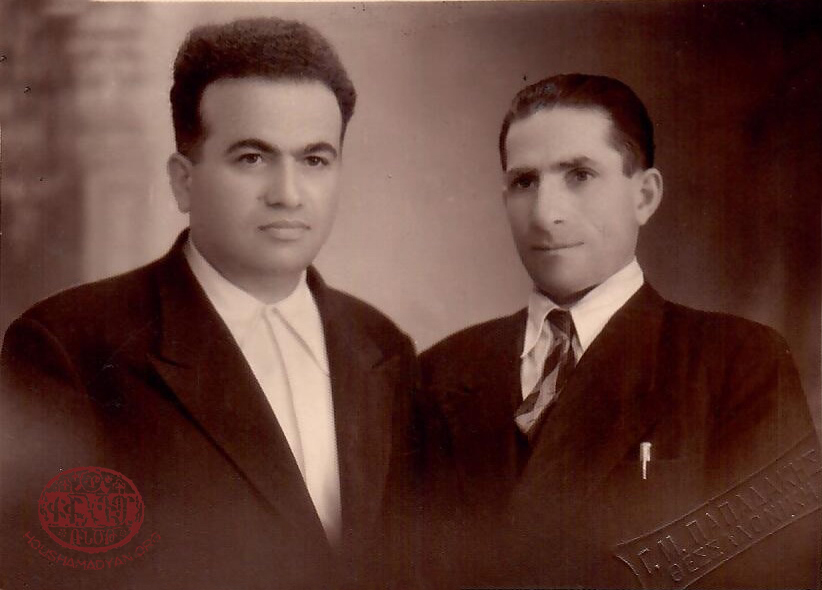

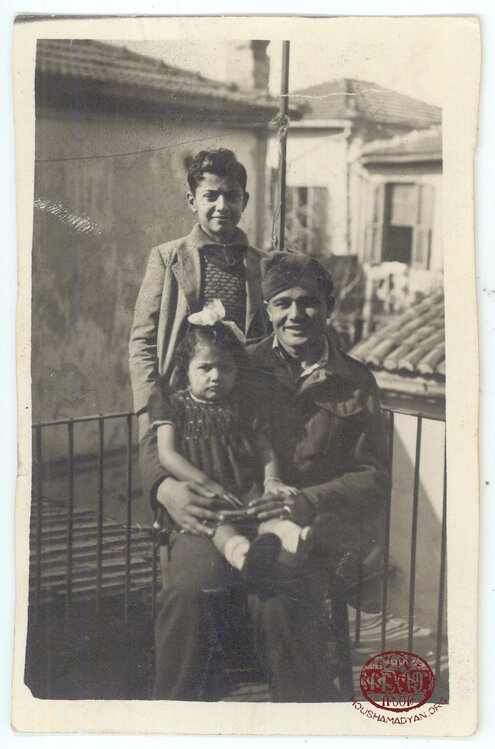

Roupen and Serop were often invited to dine with the Gazarian family. That’s how Roupen met Nvart, and the two married in 1929. Their first child was born in 1931, and was named Madteos in memory of Roupen’s father, who had been killed during the Genocide. Unfortunately, the infant died soon after birth. Their second son, Garabed, was born in 1933. Their daughter, Dirouhi, was born in 1942.

Roupen Kalfayan served as the chairman of the neighborhood council of the Thessaloniki Armenian community from 1940 to 1944, and then again from 1946 until his death in 1971.

Garabed Kalfayan married Anahid Yaghdjian/Yiagjian, and the couple had two sons, Roupen and Arsen. Dirouhi married Kosma Galileas, and the two had two children, Nevart-Veron and Christos.

Source

- Arshag Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Yevtovgyo Hayots, Deghakragan, Badmagan yev Avkakragan Deghegoutyunnerov [History of the Armenians of Evdokia, with Geographic, Historical, and Ethnographic Statistics], Cairo, Nor Asdgh Printing House, 1952.

- Arshag Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario [History of Armenian Gesaria], volumes A and B, Cairo, H. Papazian Printing House, 1937.

- Hin yev Nor Gesaria [Old and New Gesaria], Paris, Azed Printing House, Paris Branch of the Compatriotic Union of the City and Region of Gesaria, 1989.

- Asadour H. Magarian, Houshakirk Tragyo yev Magetonyo Hay Kaghoutnerou [Memory Book of the Armenian Communities of Thrace and Macedonia], Thessaloniki, Published by Horizon Newspaper, 1929.

- Hratch Dasnabedian, H. H. Tashnagtsoutyunu ir Gazmoutenen minchev J. Unth. Joghov (1890-1924) [The Armenian Revolutionary Federation from its Founding to the Tenth Party Summit (1890-1924)], Troshag Press, 1988, Athens.

- Hounahay Darekirk [Greek-Armenian Yearbook], 1927, year A, Nor Or Publications, Athens.

[1] Another source mentions that the architect who traveled to Adana with Avedis Kalfayan was Sahag kalfa Balukdjian (Hin yev Nor Gesaria, Houshamadyan [Old and New Gesaria, Memory Book], Paris, 1989, p. 254). Puzant Yeghiayan provides entirely different names for the architects of the Holy Mother of God and Saint Sdepanos churches in Adana, namely Hagop kalfa, Vartan kalfa, and Kirechdjian. However, Yeghiayan states that Hagop kalfa built these churches in the early 19th century. Presumably, Yeghiayan’s information concerns churches built at an earlier date, while Avedis began building the Holy Mother of God Church in Adana in 1867 (Puzant Yeghiayan (ed.), Adanayi Hayots Badmoutyun [History of Adana Armenians], Printing House of the Holy See of Cilicia, Antilias, 1970, p. 607).