Mardigian Collection – Thessaloniki

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 28/02/22 (Last modified 28/02/22) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The memory objects and materials presented on this page were collected and catalogued during Houshamadyan’s workshops in Thessaloniki on November 13 and 14, 2021.

This page was prepared collaboratively with the “Armenika” periodical of Athens and the Thessaloniki chapter of the Hamazkayin Cultural Association. Houshamadyan’s workshops were made possible thanks to the support of EVZ Foundation, Germany.

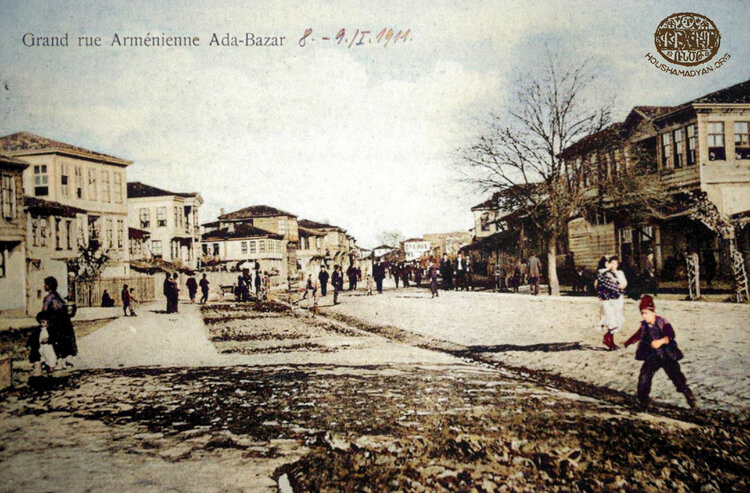

These materials were provided to us by Mardig Mardigian. The family of Mardig's wife, Manishag Mardigian (nee Kasbarian) originally hailed from Adapazar. Manishag's mother is Alice Kasbarian (nee Kupdjian). Alice's father and mother, Varaztad Kupdjian and Mary Kupdjian (nee Gulian), were both born in Adapazar.

Mary was the daughter of Makrouhi Gulian and Asadour Gulian. According to the oral history of the family, Makrouhi and Assadour had made pilgrimages both to Armash and to Jerusalem. Presumably, one of the goals of these pilgrimages was to beseech God to bless them with a child, but Makrouhi never became pregnant. Eventually, Makrouhi and Asadour decided to adopt a girl – Mary.

The Gulians owned a bakery in Adapazar, and they were a family of bakers.

During the Armenian Genocide, both the Gulian and Kupdjian families were deported. We do not know exactly which members of the two families were killed during those days of carnage. After the Armistice, the survivors returned to their homes, but after 1922, they abandoned Adapazar permanently and fled to the Greek island of Lemnos, alongside numerous refugees escaping Western Anatolia.

After remaining in Lemnos for some time, the family moved to the northern Greek city of Drama, after which they permanently settled down in Thessaloniki, where Mardig and his family still live today.

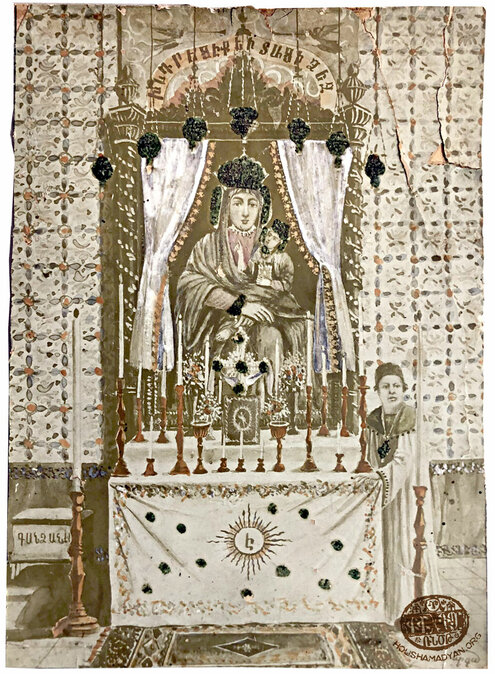

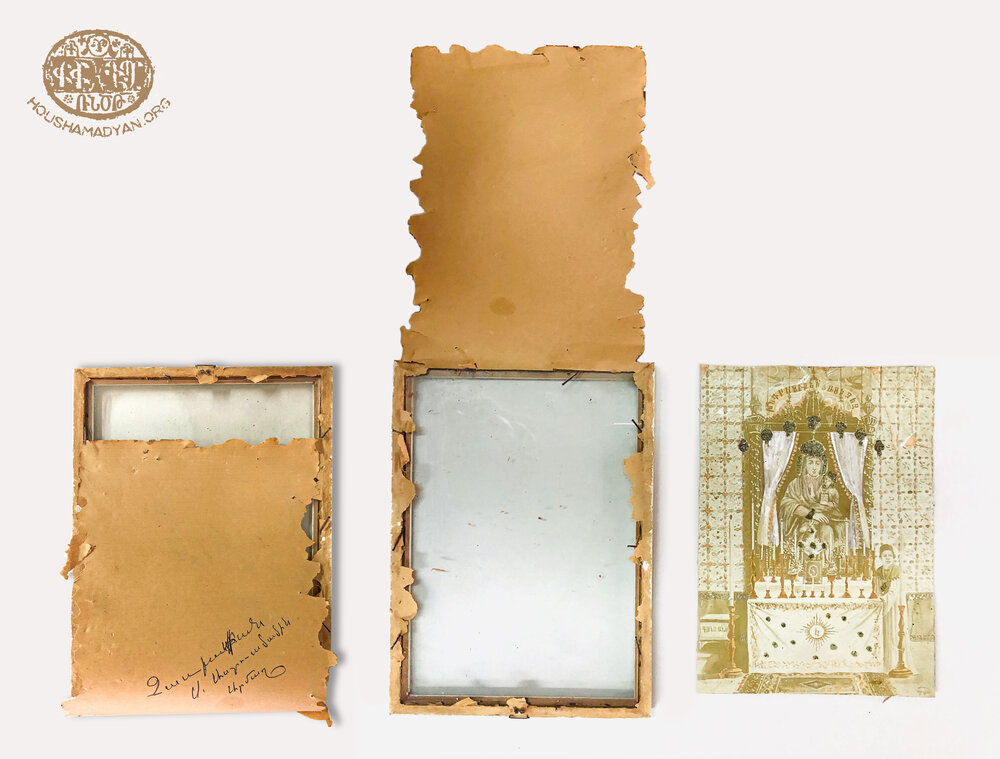

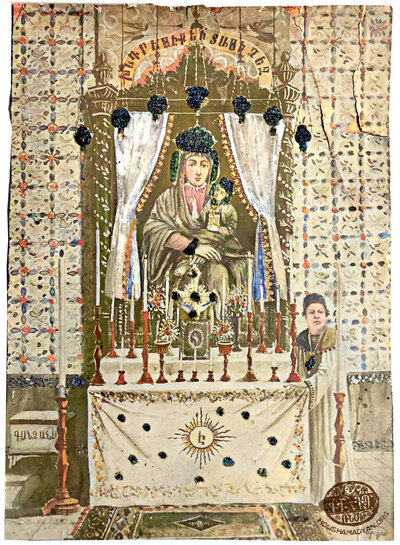

Mardig inherited only a single memory object from the family of his wife, Manishag – a unique photograph of an icon of the Holy Virgin that adorned the narthex of the church of the Armash Monastery. For many years, the photograph has been kept in a glass frame. Mardig tells us that this photograph remained in the possession of the family throughout the years of the deportations and was eventually brought by them to Greece. Makrouhi always kept the photograph hanging from a wall in her home. After her passing, the tradition was taken up by Mary. And now, it is Mardig and Manishag who carefully preserve this photograph. Alice, Manishag's mother, also remembers that when she was young, women who were acquaintances of Makrouhi’s would visit the latter’s home, and together kneel before the photograph to pray to the Holy Virgin.

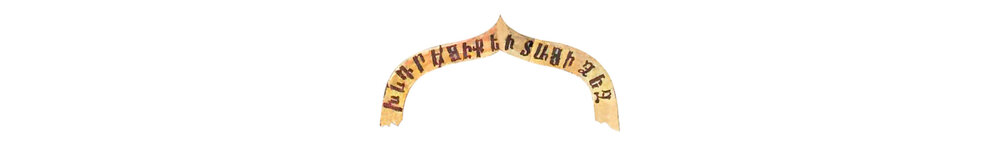

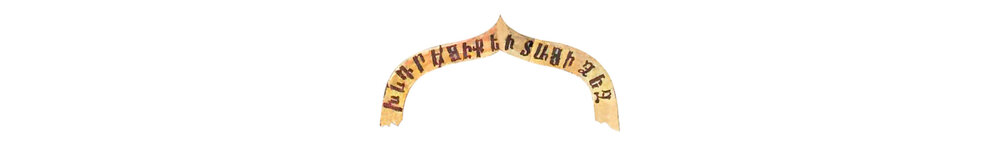

The Icon of the Charkhapan [Evil-Hinderer] Holy Virgin Monastery of Armash

In the narthex of the Charkhapan Holy Virgin Monastery of Armash was an icon of the Holy Virgin, with the infant Christ in her lap. The picture preserved by Mardig is a black-and-white photograph of this icon, later enhanced with colors and additional features, in order to give it the more reverential aspect of a sacred object. Mardig and Manishag inherited the photograph in this form from their ancestors, and they continue to keep in their home. The narthex, above the icon, bears the inscription, in classical Armenian, “Khnrestsek yev datsi tsez” [“Ask and ye shall receive”]. On the right-hand side of the photograph is a teen-aged chorister. On the left-hand side is a chest on the floor, with the inscription Kantsanag [poor box/alms box]. This must have been the chest in which visiting pilgrims placed their financial or non-financial alms.

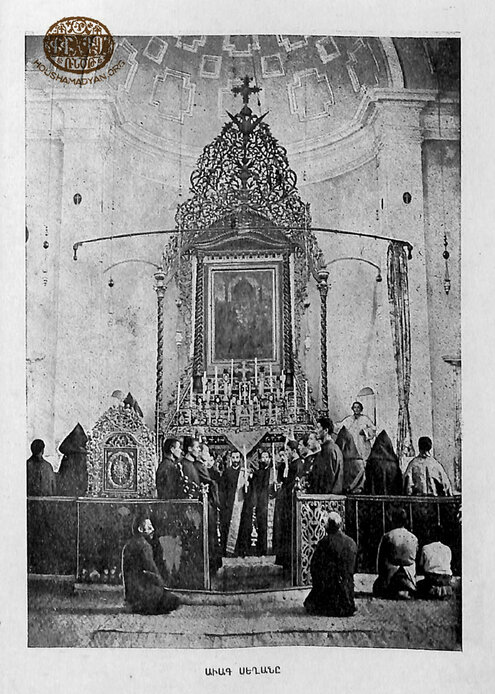

We were able to find another photograph of this icon in a book titled Armashou Tbrevankin 25-Amya Hopelyanin Artiv, 1889-1914 [On the Occasion of the 25-Year Jubilee of the Armash Seminary, 1889-1914] (M. Hovagimian Press, Constantinople, 1914, page 195). Page 95 of the same book features the photograph of the altar of the monastery’s church, captioned “Avak Seghan” [“Main Altar”]. This altar, too, featured an icon of the Holy Virgin. Additional information on both the icons is provided by Levon Pashalian, a well-known Armenian author from Constantinople. In 1892, Constantinople’s Hairenik newspaper published an impressive series of reports, authored by Pashalian, describing the Armenian pilgrims who devotedly made their way to the monastery every year. [1]

Pashalian mentions that above the narthex on the right-hand side of the church hung the image of the Hrashakordz [Miracle-Maker] Holy Virgin of Armash.

“It was a large painting, executed in the Eastern style with thick and curving lines and an intense, powerful, boisterous palette. The Holy Virgin, wearing a crown on her head, holds the infant Christ in her lap. He lacks any child-like features. In this expressionless painting, only the Holy Virgin’s large eye shows signs of life – an eye that seems to be looking down into a bottomless abyss, terrified. The gaze, in its immobility and coldness, seems to stalk you, seems to seek you out from every corner, forcing the faithful to bow their heads, as if to avoid the awful and preternatural power of that eye.” [2]

Pashalian adds that the monastery was home to another icon of the Holy Virgin, which “… was of great artistic value, in the style of the greatest of Venetian masters…” [3]. We can reasonably imply that this second icon mentioned by Pashalian was the one that adorned the church’s main altar.

Notably, in the late 19th century, the Armenians of Constantinople placed an icon of the Holy Virgin in the Saint Hovnan Vosgeperan Church of the city’s Karageomrug neighborhood. The church soon became a popular pilgrimage site, just like the Charkhapan Church of the Armash Monastery. In fact, the locals began calling this church “Little Armash.” In 1900, a large fire broke out in the church, and the local priest, at the risk of his own life, succeeded in saving the icon of the Holy Virgin. Thereafter, the icon was moved to the Saint Hreshdagabed Church of the Balat neighborhood, where it remains today, and where it still attracts devoted pilgrims. [4]

As for the Mardig’s photograph, evidently, it depicts the pilgrims’ beloved and revered Hrashakordz Holy Virgin, the Charkhapan of Armash. The pilgrims to the monastery would kneel before her and make their vows. Many years later, even the photograph of this icon continued to inspire reverence in the faithful. The altar, the narthex, the icon, and the monastery were entirely destroyed, but Makrouhi and her family, now refugees in Greece, continued to keep the photograph, which itself had become an icon and possessed the same awe-inspiring power. Refugee Armenian women, just as they had done in Armash in the past, would kneel before the photograph and pray, repeating the old rites and prayers they had learned in their homeland…

- [1] Hairenik newspaper, September 13, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25, 1892, year 23, Constantinople.

- [2] Levon Pashalian, Yerger [Collected Works], Printing House of the Holy See of Cilicia, Antilias, 1994, p. 185.

- [3] Ibid.

- [4] www.turkiyeermenileripatrikligi.org/site/hy/չարխափան-ս-աստուածածնի-սրբապատկերին/

The village of Armash (present-day Akmeşe). The monastery complex with its church, seminary, and pilgrims’ quarters. This photograph was digitally colorised using Myheritage.com.

Levon Pashalian’s chronicle of his journey to Armash, as published by the Hairenik newspaper of Constantinople. Click here to read the complete text. (Source: Levon Pashalian, Yerger [Collected Works], Printing House of the Holy See of Cilicia, Antilias, 1994)